Published online Jan 6, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i1.135

Peer-review started: August 27, 2022

First decision: October 21, 2022

Revised: November 4, 2022

Accepted: December 9, 2022

Article in press: December 9, 2022

Published online: January 6, 2023

Processing time: 120 Days and 11.2 Hours

Polyneuropathy organomegaly endocrinopathy M-protein and skin changes (POEMS) syndrome is a rare paraneoplastic syndrome caused by a potential plasma cell tumor. The clinical manifestations of POEMS syndrome are diverse. Due to the insidious onset and lack of specific early-stage manifestations, POEMS syndrome is easily misdiagnosed or never diagnosed, leading to delayed treatment. Neurological symptoms are usually the first clinical manifestation, while ascites is a rare symptom in patients with POEMS syndrome.

A female patient presented with unexplained ascites as an initial symptom, which is a rare early-stage manifestation of the condition. After 1 year, the patient gradually developed progressive renal impairment, anemia, polyserosal effusion, edema, swollen lymph nodes on the neck, armpits, and groin, and decreased muscle strength of the lower extremities. The patient was eventually diagnosed with POEMS syndrome after multidisciplinary team discussion. Treatment comprised bortezomib + dexamethasone, continuous renal replacement therapy, chest and abdominal closed drainage, transfusions of erythrocytes and platelets, and other symptomatic and supportive treatments. The patient’s condition initially improved after treatment. However, then her symptoms worsened, and she succumbed to the illness and died.

Ascites is a potential early manifestation of POEMS syndrome, and this diagnosis should be considered for patients with unexplained ascites. Furthermore, multidisciplinary team discussion is helpful in diagnosing POEMS syndrome.

Core Tip: Polyneuropathy organomegaly endocrinopathy M-protein and skin changes (POEMS) syndrome is a rare paraneoplastic syndrome caused by a potential plasma cell tumor. The clinical manifestations of POEMS syndrome are diverse, and the syndrome is often misdiagnosed or never diagnosed, resulting in delayed treatment and a poor outcome. Ascites might be an early clinical manifestation of POEMS syndrome. Thus, POEMS syndrome should be considered as a potential diagnosis for patients with unexplained ascites. Furthermore, multidisciplinary team discussion is helpful in the diagnosis of POEMS syndrome.

- Citation: Zhou XL, Chang YH, Li L, Ren J, Wu XL, Zhang X, Wu P, Tang SH. Polyneuropathy organomegaly endocrinopathy M-protein and skin changes syndrome with ascites as an early-stage manifestation: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(1): 135-142

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i1/135.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i1.135

Polyneuropathy organomegaly endocrinopathy M-protein and skin changes (POEMS) syndrome is a rare paraneoplastic syndrome caused by a potential plasma cell tumor, with an incidence of only 0.3/100000. POEMS syndrome is named after five common features of the syndrome: Polyneuropathy; organomegaly; endocrinopathy; monoclonal plasma cell disorder; and skin changes. Due to the insidious onset and lack of specific early manifestations, diagnosis of POEMS syndrome is often difficult, leading to misdiagnoses and delayed treatment. The primary symptom(s) and course of POEMS syndrome are extremely complex and vary at different stages. Neurological symptoms such as muscle weakness are often the first symptoms in most patients. Here, a rare case of POEMS syndrome with ascites as the early manifestation was reported.

A 51-year-old woman was admitted to the hospital for the fifth time with abdominal distension for 9 mo.

For 9 mo, the patient had abdominal distension, accompanied by edema of the lower extremities, anorexia, and fatigue. The patient underwent the following ancillary tests before the fifth admission to hospital. Urine was positive for protein and occult blood, while 24-h urine protein was 0.19 g/L and urine microalbumin was 74.1 mg/L. Thyroid function indicated thyrotropin of 5.183 mIU/L, free thyroxine of 1.17 ng/dL, and iodothyronine of 1.1 pg/mL. Immunoglobulin G was 18.0 g/L, and complement C3 was 0.66 g/L. Purified protein derivative test and tuberculosis antibody test were positive.

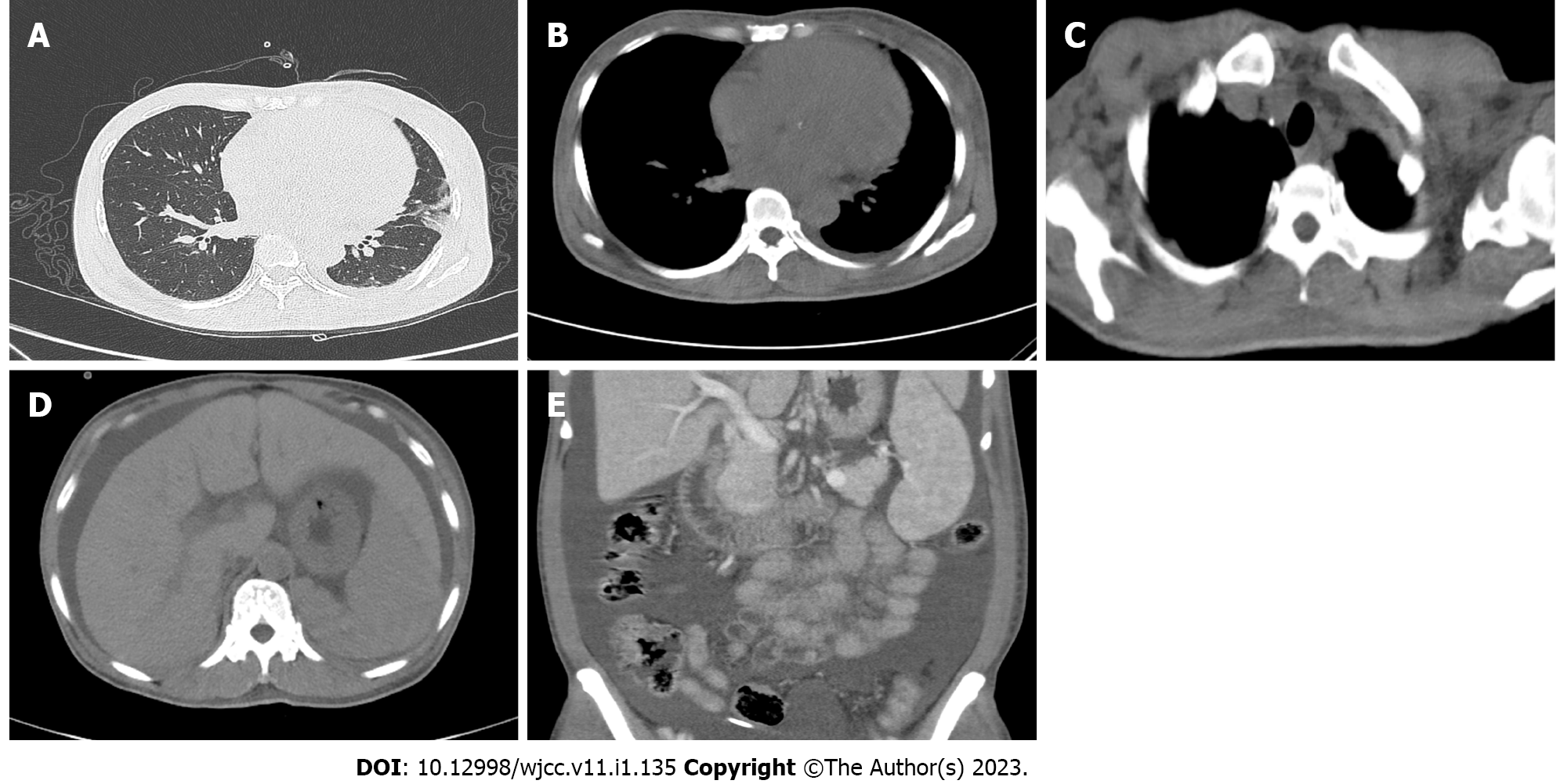

FibroScan showed liver stiffness of 21.9 kPa, while the electrocardiogram showed a heavy load of the right atrium. Enhanced computed tomography (CT) of the head, chest, and abdomen on March 16, 2021 revealed inflammatory changes in the lingual segment of the upper lobe of the left lung and lower lobe of both lungs, slight enlargement of the heart, slightly thickened bilateral pleura and a small amount of effusion in the left pleural cavity, some enlarged lymph nodes in the mediastinum and bilateral axilla, suspected liver cirrhosis, splenomegaly, and abdominal and pelvic hydrops, swollen and thick intestinal walls, and blurred fat space in the abdominal and pelvic cavity (Figure 1). Biopsies of cervical and inguinal lymph nodes showed reactive lymphoid hyperplasia.

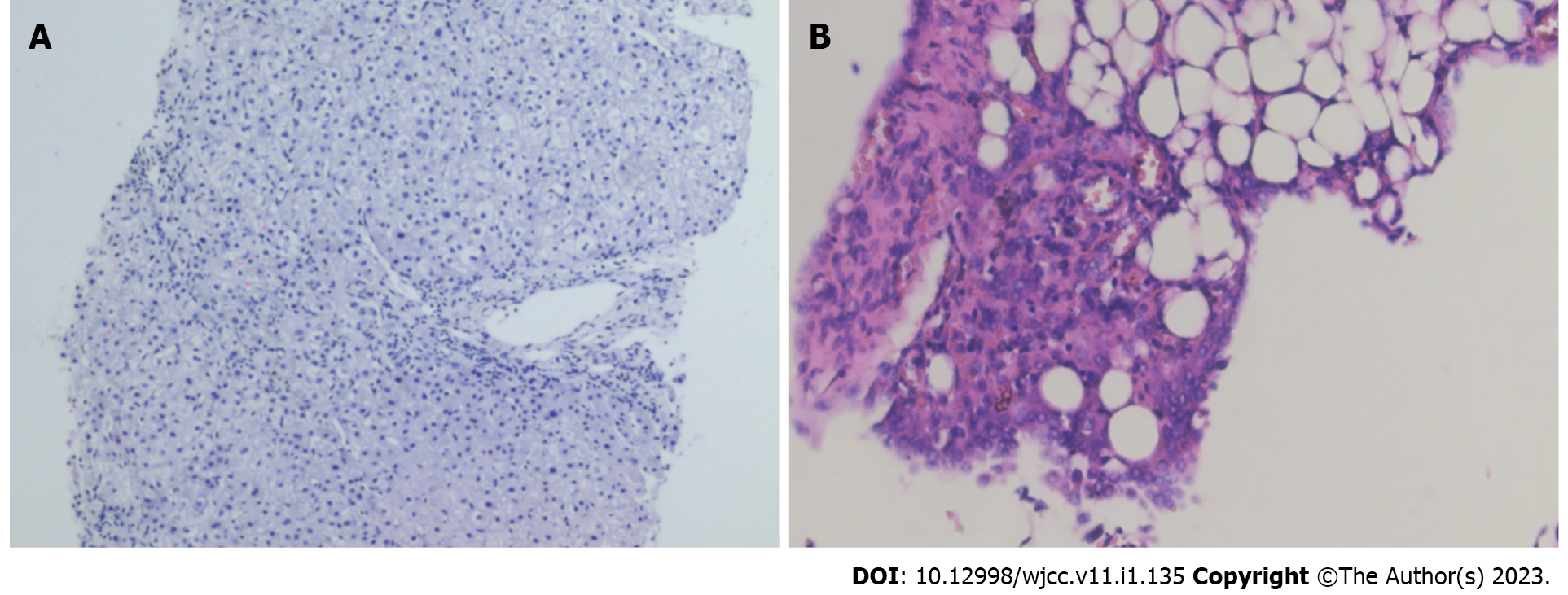

The Rivalta test of ascites fluid was negative, and pathology of ascites fluid indicated that a large number of inflammatory cells were present. Laboratory tests of ascites fluid showed a nucleated cell count of 120 × 106/L, a red blood cell count of 110 × 106/L, 80% mononuclear cells and 20% polynuclear cells, total protein of 43 g/L, and glucose of 8.17 mmol/L. The bone marrow smear showed active proliferation of nucleated cells, while the bone marrow biopsy showed active bone tissue proliferation. Liver biopsy illustrated chronic hepatitis G1/S1 (Figure 2A).

Positron emission tomography-CT scans showed multiple slightly larger lymph nodes with mildly increased 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose metabolism in the bilateral neck, clavicle area, mediastinum, bilateral axilla, retroperitoneum, and inguinal area, which were consistent with lymph node inflammatory hyperplasia changes. Hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, and enlarged heart and massive effusion in the abdominal and pelvic cavity were observed. Ultrasound-guided peritoneal biopsy showed interstitial edema with a small number of inflammatory cells and mesothelial hyperplasia. Routine blood test, liver and kidney function, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, tuberculosis γ-interferon release assay, portal vein ultrasound, gastroscopy, and colonoscopy results were all negative.

The patient received diagnostic anti-tuberculosis therapy (rifampicin 0.45 g qd + isoniazid 0.3 g qd + pyrazinamide 1.50 g qd + ethambutol 0.75 g qd) in the 5 mo prior to admission. She had a poor response to this therapy, accompanied by progressive renal insufficiency, oliguria, and anemia, and treatment was stopped 2 mo prior to admission. Moreover, the patient underwent a laparoscopy during the diagnostic anti-tuberculosis therapy, which indicated the presence of inflammation and edema of the intra-abdominal tissue, especially on the right upper quadrant of the liver and diaphragm, a pus coating, and approximately 1000 mL pale yellow ascites fluid. Peritoneal and omental biopsies revealed inflammatory lesions (Figure 2B).

Due to papillary thyroid cancer, the patient underwent a total thyroidectomy, bilateral neck lymph node dissection, and a parathyroid transplantation 4 years prior. No tumor cells were found in the enlarged superficial lymph nodes that were removed during the operation. There were no obvious abnormalities in the bone marrow smear and biopsy at that time. The patient was diagnosed with high blood pressure 2 years prior. She had a cholecystectomy because of cholelithiasis in 2020.

There was nothing remarkable in the patient’s personal and family history.

The patient was emaciated. Bilateral swollen lymph nodes, approximately 3-5 mm, were noted on the neck, armpits, and groin. The lymph nodes were firm, flexible, and without tenderness. Abdominal shifting dullness was positive. Muscle strength of the bilateral lower extremities decreased to level 1. There were no signs of jaundice, lower extremity edema, abdominal tenderness, or pulmonary rales.

Arterial blood gas analysis showed metabolic acidosis (pH 7.2; oxygen partial pressure 69 mmHg; oxygen saturation 89%; actual bicarbonate 10.6 mmol/L; standard bicarbonate 12.6 mmol/L; total carbon dioxide 11.8 mmol/L). Renal function tests indicated renal failure (urea nitrogen of 41.77 mmol/L; creatinine 441 μmol/L; endogenous creatinine clearance rate 24.5 mL/min). Brain natriuretic peptide was 234.37 pg/mL. Routine blood examination showed anemia and thrombocytopenia (white blood cell 5.06 × 109/L; hemoglobin 50 g/L; platelet count 48 × 109/L). Routine and biochemical examination of ascites fluid showed increased total protein (39.2 g/L) and a positive result in the mucin qualitative test. The serum ascites albumin gradient was 8.2 g/L, indicating that the ascites was exudate. Peripheral blood free light chain measurements were: κ light chain 96.36 mg/L; λ light chain 333 mg/L; and κ/λ 0.2894.

Blood immunofixation electrophoresis revealed immunoglobulin G-λ type. Serum protein electrophoresis showed α1 globulin at 6.84%. M protein was positive. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) was increased to 221.23 pg/mL (1.56 × upper limit of normal). An abnormally elevated concentration of prolactin was detected (44.98 ng/mL). Furthermore, nerve conduction velocity showed demyelination of extremity nerves with axonal changes involving motor and sensory nerve fibers, chronic neurogenic damage in both upper extremities, damaged lower motor neuron nerve roots, and abnormal conduction of skin-spinal cord-extremity sensory pathway. Meanwhile, peripheral blood immunoglobulin G4, human herpesvirus 8, and metagenomic next-generation sequencing tests of ascites fluid and blood were all negative.

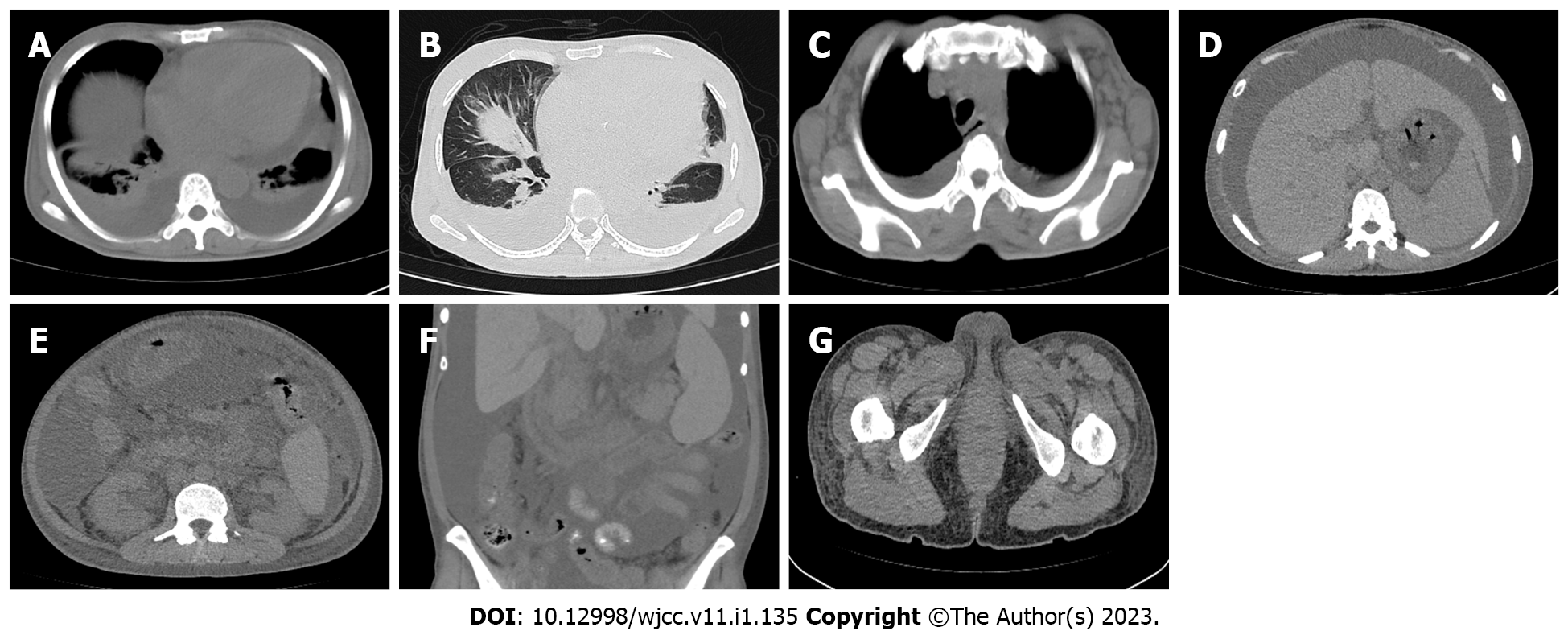

A chest CT on November 12, 2021 showed moderate effusion in the bilateral pleural cavities and a small amount of effusion in the left lobe fissure, which was significantly more than that seen in previous images on March 16, 2021. Multiple inflammatory changes were scattered in both lungs and were increased compared with previous images. The heart was enlarged more than in the earlier images, and moderate effusion in the pericardium was evident compared with earlier images. The bilateral pleura was slightly thickened. There were multiple lymph nodes in the mediastinum and bilateral axilla; some of them were enlarged. An abdominal CT found multiple enlarged lymph nodes in the retroperitoneum and bilateral groin, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, increased abdominal pelvic effusion, a thickened gastrointestinal wall, blurred fat space in the abdominal cavity and pelvis, thickened perirenal fascia, a small cyst in the left lateral lobe of the liver, absence of the gallbladder, and soft tissue edema of the waist, abdomen, and buttocks (Figure 3).

Considering that the patient had polyneuropathy, monoclonal plasma cell dysplasia, a significantly increased concentration of VEGF, liver enlargement, extravascular volume overload, and elevated prolactin, she was diagnosed with POEMS syndrome following multidisciplinary team consultation and discussion.

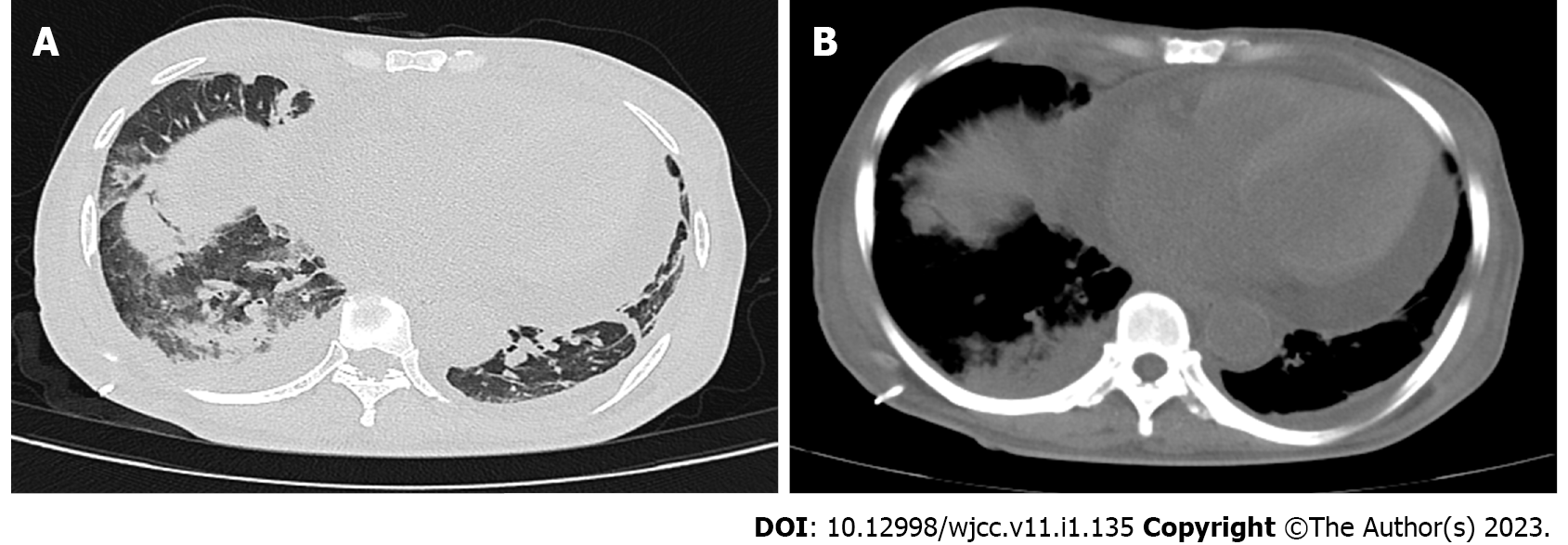

The patient received chest and abdominal closed drainage, transfusions of erythrocytes and platelets, methylprednisolone (intravenous injection 80 mg qd for 1 wk), piperacillin sodium/sulbactam sodium anti-infective treatment, and continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) after admission. A repeated chest and abdomen CT on December 2, 2021 showed that pleural effusion had decreased after the initial treatment. However, pulmonary infection was aggravated, and pericardial effusion was increased (Figure 4). Following the final diagnosis, the patient received chemotherapy regimens (bortezomib 2 mg D1, 5, 8, 12 + dexamethasone 40 mg D1, 2, 5, 6, 8, 9, 12, 13). The patient subsequently presented with oliguria, gastrointestinal symptoms, dyspnea, and metabolic acidosis, which were due to tumor lysis syndrome. All symptoms mentioned above improved after CRRT. Cytokine concentrations in the peripheral blood and ascites fluid returned to normal. Muscle strength of the bilateral lower extremities recovered to level 3. All treatments were administered with the patient’s informed consent.

The patient received a second cycle of chemotherapy (bortezomib 2 mg D1, 5 + dexamethasone 40 mg D1, 2, 5, 6) 3 wk after the end of the first cycle of chemotherapy. After these second chemotherapy regimens, the patient presented with renal failure, dyspnea, and metabolic acidosis, again due to tumor lysis syndrome, and received CRRT for 3 d. At this point, brain natriuretic peptide had decreased from 17908.79 pg/mL to 7872.74 pg/mL, while arterial blood gas analysis showed recovered pH (from 7.06 to 7.28), carbon dioxide partial pressure (from 86 to 60 mmHg), and oxygen partial pressure (from 56 to 134 mmHg). However, the patient presented with dyspnea and metabolic acidosis 5 d after this CRRT. The patient refused all further medical treatment and died 1 d after hospital discharge.

POEMS syndrome was proposed by Bardwick et al[1] in 1980 and is a rare paraneoplastic syndrome caused by latent plasma cell tumors, with an incidence rate of 0.3/100000[2]. Clinical manifestations of POEMS syndrome are diverse, and early-stage manifestations are not specific. Organomegaly, endocrine disease, monoclonal gammopathy, and skin changes are common early-stage symptoms, while neurological symptoms are the most prevalent early-stage manifestations. However, ascites is an extremely rare early-stage symptom for patients with POEMS syndrome. After excluding tuberculosis, liver cirrhosis, hypothyroidism, tumors, and other diseases, ascites was considered to be caused by POEMS syndrome in this case.

POEMS syndrome has an insidious onset and atypical symptoms. Patients usually cannot be diagnosed until various clinical manifestations have appeared. Therefore, diagnosis is a lengthy process and patients are easily misdiagnosed or sometimes never diagnosed. Consequently, the optimum time for treatment has often been missed by the time a patient is diagnosed with POEMS syndrome. The general diagnostic criteria for POEMS syndrome include essential criteria (polyneuropathy, monoclonal plasma cell dysplasia), important criteria (sclerosing bone lesions, Castlemen’s disease, elevated VEGF concentration), minor criteria (organ enlargement, extravascular volume overload, endocrinopathy, skin changes, optic disc edema, thrombocytosis/polycythemia), and other symptoms and signs (weight loss, hyperhidrosis, clubbing, increased pulmonary arterial pressure, diarrhea). Patients with two essential criteria + at least one important criterion + at least one minor criterion can be diagnosed as having POEMS syndrome[3].

To simplify the diagnostic criteria and improve the early diagnosis rate, Suichi et al[4] recently proposed new diagnostic criteria for POEMS syndrome. These new criteria include three primary criteria (polyneuropathy, monoclonal proliferative disease, and elevated VEGF) and four secondary criteria (extravascular volume overload, skin changes, enlarged organ, and sclerosing bone lesions). Patients with three major criteria and at least two minor criteria can be defined as having POEMS syndrome[4]. The patient in this report met the general diagnostic criteria (two essential criteria: polyneuropathy and monoclonal plasmacytosis; one important criterion: elevated VEGF concentration; three minor criteria: hepatomegaly, extravascular volume overload and edema, and endocrinopathy; other symptoms and phenomena: weight loss) and the new diagnostic criteria (three main criteria: polyneuropathy, monoclonal proliferative disorders, and elevated VEGF; two minor criteria: extravascular volume overload, hepatomegaly). According to these diagnostic criteria, the patient was diagnosed with POEMS syndrome.

The etiology and pathogenesis of POEMS syndrome have yet to be elucidated. Some mechanisms in the pathogenesis of POEMS syndrome have been reported in previous studies[5]. Monoclonal plasma cell proliferation, which leads to abnormal secretion of M protein, can affect the nervous system, endocrine system, hematopoietic system, and reticuloendothelial system and cause dysfunction of these systems[6]. Excessive secretion of inflammatory cytokines leads to inflammation and demyelination of peripheral nerves, causing skin damage and neuropathic edema[7].

Increased VEGF secretion increases vascular permeability and blood vessel formation, resulting in polyneuropathy, organ enlargement, skin changes, endocrine dysfunction, and papilledema[8,9]. Recent studies demonstrated that VEGF is not only instrumental in the pathogenesis of POEMS syndrome but is also an important indicator for diagnostic criteria and efficacy evaluation[10]. Since mild elevation of VEGF rarely occurs in inflammatory demyelinating neuropathies and hematological malignancies, the combination of elevated VEGF and λ light chain is essential to the diagnosis of POEMS syndrome[11].

Furthermore, for patients with POEMS syndrome, the serum concentration of VEGF after 6 mo of treatment is a prognostic biomarker. Serum VEGF can be used as a surrogate endpoint for relapse-free survival or clinical/laboratory improvement in patients with POEMS syndrome[12]. For the patient in this case report, the concentration of VEGF in ascites fluid and blood was significantly increased, which verified the diagnosis of POEMS syndrome and indicated poor prognosis.

As a multifunctional cytokine, interleukin (IL)-6 plays a vital role in various functions such as inducing the differentiation of B cells into antibody-producing cells, differentiation of T cells and nerve cells, and activation of acute phase proteins in hepatocytes and hematopoietic cells. According to a recent study, IL-6 could be the pathogenic factor that induces various clinical symptoms and pathological features of POEMS syndrome[13]. The concentrations of IL-4, IL-6, and IL-10 were significantly increased in blood, ascites fluid, and pericardial effusion in the patient in this case report. After the first course of chemotherapy, the concentrations of IL-4, IL-6, and IL-10 in peripheral blood returned to normal, indicating that treatment was effective. Immune activation and increased inflammatory status may contribute to the pathogenesis of ascites in POEMS syndrome[14].

The median survival time of patients with POEMS syndrome is 5 years to 7 years, which indicates that the prognosis of POEMS syndrome is poor. The survival time depends on the type and status of the complications. Diagnosis during the early stage of the condition is beneficial to improve the prognosis of patients with POEMS syndrome[15]. Multiple swollen lymph nodes were found in our patient during previous thyroid cancer surgery. However, the postoperative pathology only suggested reactive lymph node hyperplasia and not neoplastic disease. It is possible that the swollen lymph nodes may be the first symptom of POEMS syndrome. The patient was not diagnosed with POEMS syndrome until she developed polyserosal effusion, edema, decreased muscle strength of lower extremities, and weight loss and had completed various examinations such as positron emission tomography-CT scans and blood immunofixation electrophoresis and received multidisciplinary team consultation. It may have taken more than 4 years since the onset of the first symptoms to the final diagnosis; consequently, the patient had a poor prognosis because the optimal treatment opportunity had been missed.

There is no effective treatment for POEMS syndrome, and chemotherapy is the predominant treatment choice. Commonly used chemotherapy treatment regimens include lenalidomide + dexamethasone, bortezomib + dexamethasone, cyclophosphamide + adriamycin + vincristine + prednisone, chimeric antigen receptor T cell immunotherapy, autologous stem cell transplantation, and radiation therapy[3]. Bortezomib combined with dexamethasone has good efficacy and remission rate and less adverse reactions for the initial treatment of patients with POEMS syndrome[16].

In consideration of the poor renal function in the patient in this case report, bortezomib + dexamethasone chemotherapy was applied to avoid serious complications such as renal failure. Polyneuropathy and cachexia are the leading causes of death in patients with POEMS syndrome[17]. The lower extremity muscle strength of the patient in this report decreased from grade 5 to grade 1 within half a month, accompanied by emaciation. The rapidly decreased muscle strength in the lower extremities and the emaciation, as obvious manifestations of polyneuropathy and cachexia, respectively, suggested rapid progression of the disease. The patient subsequently died 1 mo after initial treatment.

POEMS syndrome does not have specific clinical manifestations. A neurological lesion is the most common initial symptom of POEMS syndrome, while ascites is a rare early-stage manifestation. Due to the lack of specific early-stage manifestations, POEMS syndrome is easily misdiagnosed or never diagnosed, leading to delayed treatment. In this case, the time from onset to diagnosis was 4 years. Consequently, the patient had missed the best chance of treatment by the time she was finally diagnosed. Therefore, for patients with unexplained ascites, POEMS syndrome should be considered as a potential diagnosis. Furthermore, multidisciplinary team discussion is conducive to diagnosis of POEMS syndrome as well as improving the prognosis of patients.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Protopapas AA, Greece; Thandassery RB, United States S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Fan JR

| 1. | Bardwick PA, Zvaifler NJ, Gill GN, Newman D, Greenway GD, Resnick DL. Plasma cell dyscrasia with polyneuropathy, organomegaly, endocrinopathy, M protein, and skin changes: the POEMS syndrome. Report on two cases and a review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1980;59:311-322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 481] [Cited by in RCA: 416] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Nasu S, Misawa S, Sekiguchi Y, Shibuya K, Kanai K, Fujimaki Y, Ohmori S, Mitsuma S, Koga S, Kuwabara S. Different neurological and physiological profiles in POEMS syndrome and chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2012;83:476-479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Dispenzieri A. POEMS Syndrome: 2019 Update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2019;94:812-827. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 21.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Suichi T, Misawa S, Sato Y, Beppu M, Sakaida E, Sekiguchi Y, Shibuya K, Watanabe K, Amino H, Kuwabara S. Proposal of new clinical diagnostic criteria for POEMS syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2019;90:133-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Nozza A. POEMS SYNDROME: an Update. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2017;9:e2017051. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Abe D, Nakaseko C, Takeuchi M, Tanaka H, Ohwada C, Sakaida E, Takeda Y, Oda K, Ozawa S, Shimizu N, Masuda S, Cho R, Nishimura M, Misawa S, Kuwabara S, Saito Y. Restrictive usage of monoclonal immunoglobulin lambda light chain germline in POEMS syndrome. Blood. 2008;112:836-839. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kanai K, Sawai S, Sogawa K, Mori M, Misawa S, Shibuya K, Isose S, Fujimaki Y, Noto Y, Sekiguchi Y, Nasu S, Nakaseko C, Takano S, Yoshitomi H, Miyazaki M, Nomura F, Kuwabara S. Markedly upregulated serum interleukin-12 as a novel biomarker in POEMS syndrome. Neurology. 2012;79:575-582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Warsame R, Yanamandra U, Kapoor P. POEMS Syndrome: an Enigma. Curr Hematol Malig Rep. 2017;12:85-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Yokouchi H, Baba T, Misawa S, Kitahashi M, Oshitari T, Kuwabara S, Yamamoto S. Changes in subfoveal choroidal thickness and reduction of serum levels of vascular endothelial growth factor in patients with POEMS syndrome. Br J Ophthalmol. 2017;101:786-790. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Zhao H, Cai H, Wang C, Huang XF, Cao XX, Zhang L, Zhou DB, Li J. Prognostic value of serum vascular endothelial growth factor and hematological responses in patients with newly-diagnosed POEMS syndrome. Blood Cancer J. 2018;8:37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kuwabara S, Suichi T, Misawa S. 'Early VEGF testing in inflammatory neuropathy avoids POEMS syndrome misdiagnosis and associated costs' by Marsh et al. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2021;92:118-119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Misawa S, Sato Y, Katayama K, Hanaoka H, Sawai S, Beppu M, Nomura F, Shibuya K, Sekiguchi Y, Iwai Y, Watanabe K, Amino H, Ohwada C, Takeuchi M, Sakaida E, Nakaseko C, Kuwabara S. Vascular endothelial growth factor as a predictive marker for POEMS syndrome treatment response: retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e009157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Nakazawa K, Itoh N, Shigematsu H, Koh CS. An autopsy case of Crow-Fukase (POEMS) syndrome with a high level of IL-6 in the ascites. Special reference to glomerular lesions. Acta Pathol Jpn. 1992;42:651-656. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Cui RT, Yu SY, Huang XS, Zhang JT, Li F, Pu CQ. The characteristics of ascites in patients with POEMS syndrome. Ann Hematol. 2013;92:1661-1664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Faizan U, Sana MK, Farooqi MS, Hashmi H. Efficacy and Safety of Regimens Used for the Treatment of POEMS Syndrome- A Systematic Review. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2022;22:e26-e33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Gao XM, Yu YY, Zhao H, Cai H, Zhang L, Cao XX, Zhou DB, Li J. Bortezomib plus dexamethasone as first-line therapy for patients with POEMS syndrome. Ann Hematol. 2021;100:2755-2761. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Rose C, Mahieu M, Hachulla E, Facon T, Hatron PY, Bauters F, Devulder B. [POEMS syndrome]. Rev Med Interne. 1997;18:553-562. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |