Published online Mar 26, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i9.2969

Peer-review started: November 21, 2021

First decision: December 27, 2021

Revised: January 4, 2022

Accepted: February 10, 2022

Article in press: February 10, 2022

Published online: March 26, 2022

Processing time: 121 Days and 2.8 Hours

Bone marrow metastasis is common in liver and lung cancer, but there are few reports on bone marrow metastasis in colon cancer. To date, there are no such reports from mainland China, and reports of bone marrow metastasis with septic shock as the main manifestation are even rarer.

A 71-year-old woman with sepsis as the first symptom presented with high fever, low blood pressure and high inflammation indicators. Computed tomography (CT) examination revealed mild inflammation of the lungs and no obvious abnormalities in the abdomen. Blood culture suggested Escherichia coli, Aeromonas hydrophila and Aeromonas caviae infection. Antibiotic treatment significantly improved the patient’s sepsis symptoms; however, her thrombocytopenia (TCP) could not be corrected despite repeated platelet transfusions. Many malignant cells were ultimately found following a bone marrow puncture smear, and further positron emission tomography/CT (PET/CT) examination confirmed that the malignant tumor in the ascending colon was accompanied by multiple metastases, including the liver and bones. Colon adenocarcinoma was confirmed by autopsy.

Patients with advanced colon cancer may not have typical clinical symptoms, and sepsis may be the first symptom. When patients have severe TCP that cannot be explained by sepsis of intestinal origin, it is necessary to be aware of the possibility of bone marrow metastasis of intestinal tumors. As such patients often cannot tolerate endoscopy, bone marrow biopsy smears or biopsy tests for specialized cells can help obtain a diagnosis, especially in less developed countries where PET/CT is scarce.

Core Tip: Colon cancer symptoms are often not obvious, and the incidence of secondary bone marrow metastasis is low. Once secondary intestinal sepsis and refractory thrombocytopenia occur, bone marrow aspiration can help confirm the diagnosis promptly.

- Citation: Wang HJ, Zhou CJ. Occult colon cancer with sepsis as the primary manifestation identified by bone marrow puncture: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(9): 2969-2975

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i9/2969.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i9.2969

Colon cancer is a common malignant tumor[1]. Blood metastasis typically occurs in the advanced stages of the disease. The most common sites of metastasis are the liver and lung, followed by the lymph nodes; implantation metastasis also occurs. Bone marrow metastasis is extremely rare in clinical practice[2,3]. Bone marrow metastasis usually occurs in the advanced stage of the disease. Due to poor bone marrow reserves, hematopoietic function is affected, and patient tolerance to radiotherapy and chemotherapy is poor. Colorectal cancer with bone marrow metastasis is associated with a very poor prognosis. However, bone marrow metastasis has no typical symptoms or manifestations, and early clinical detection is challenging. Here, the case of a patient with bone marrow-metastatic colon cancer presenting with sepsis as the primary manifestation is reported to improve understanding of the disease.

The patient developed a fever 3 h prior to admission with a peak temperature of 39 °C.

Fever in this patient was accompanied by chills, but no cough, expectoration, pharyngeal pain, abdominal pain, diarrhea, increased urination frequency, increased urination urgency, perianal pain and other symptoms.

The patient was a 71-year-old female who had experienced hypertension for 3 years. She took oral valsartan capsules 80 mg daily which controlled her blood pressure.

There was no other special medical history or family history.

The patient was anemic, with wet rales in the right lung, regular heart rhythm, no obvious tenderness or rebound pain in the abdomen, no obvious masses in the abdomen, and no edema in the limbs.

Routine blood examination showed the following: White blood cell (WBC) count 13.2 × 109/L, neutrophil percentage 88.5%, hemoglobin (Hb) 66 g/L, platelet (PLT) count 11 × 109/L, and blood glucose 33 mmol/L.

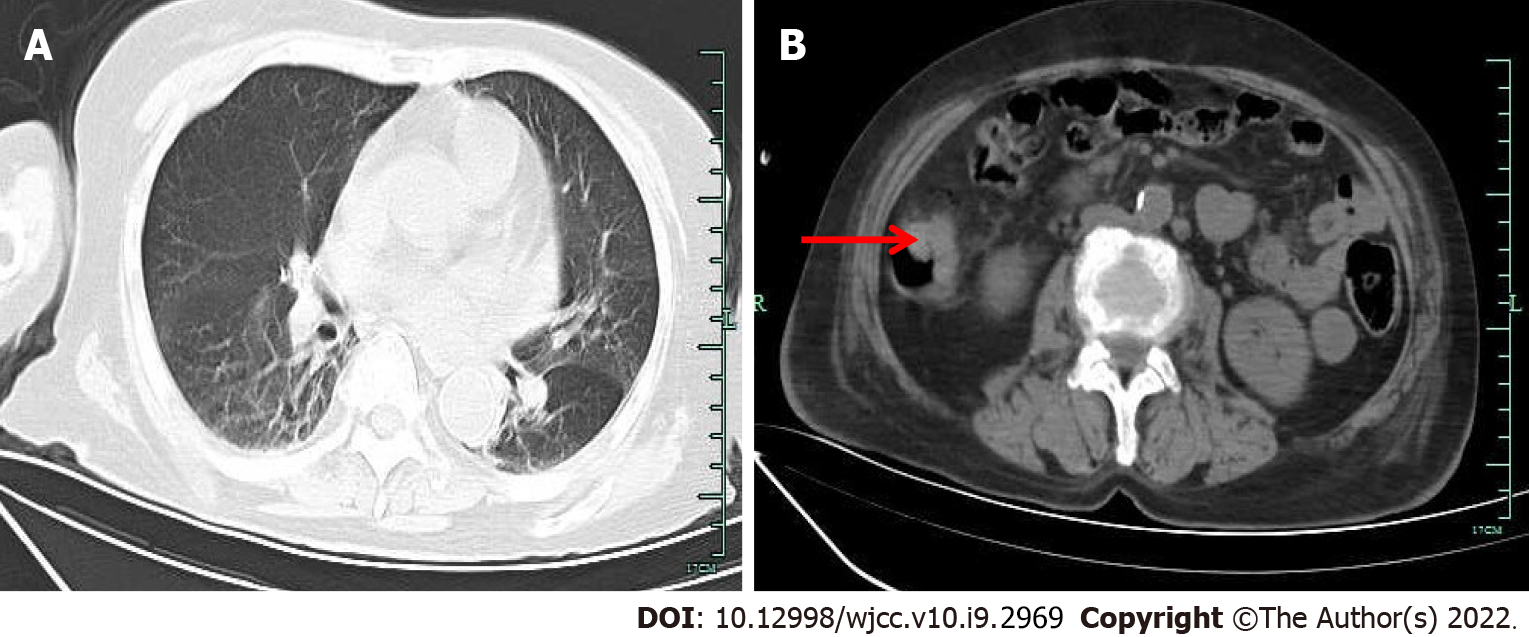

Chest and abdominal computed tomography (CT) examination revealed inflammation in both lungs and bilateral pleural thickening (Figure 1).

The suspected diagnoses on admission were as follows: Fever of undetermined origin (potentially indicating severe sepsis); pneumonia; hypertension.

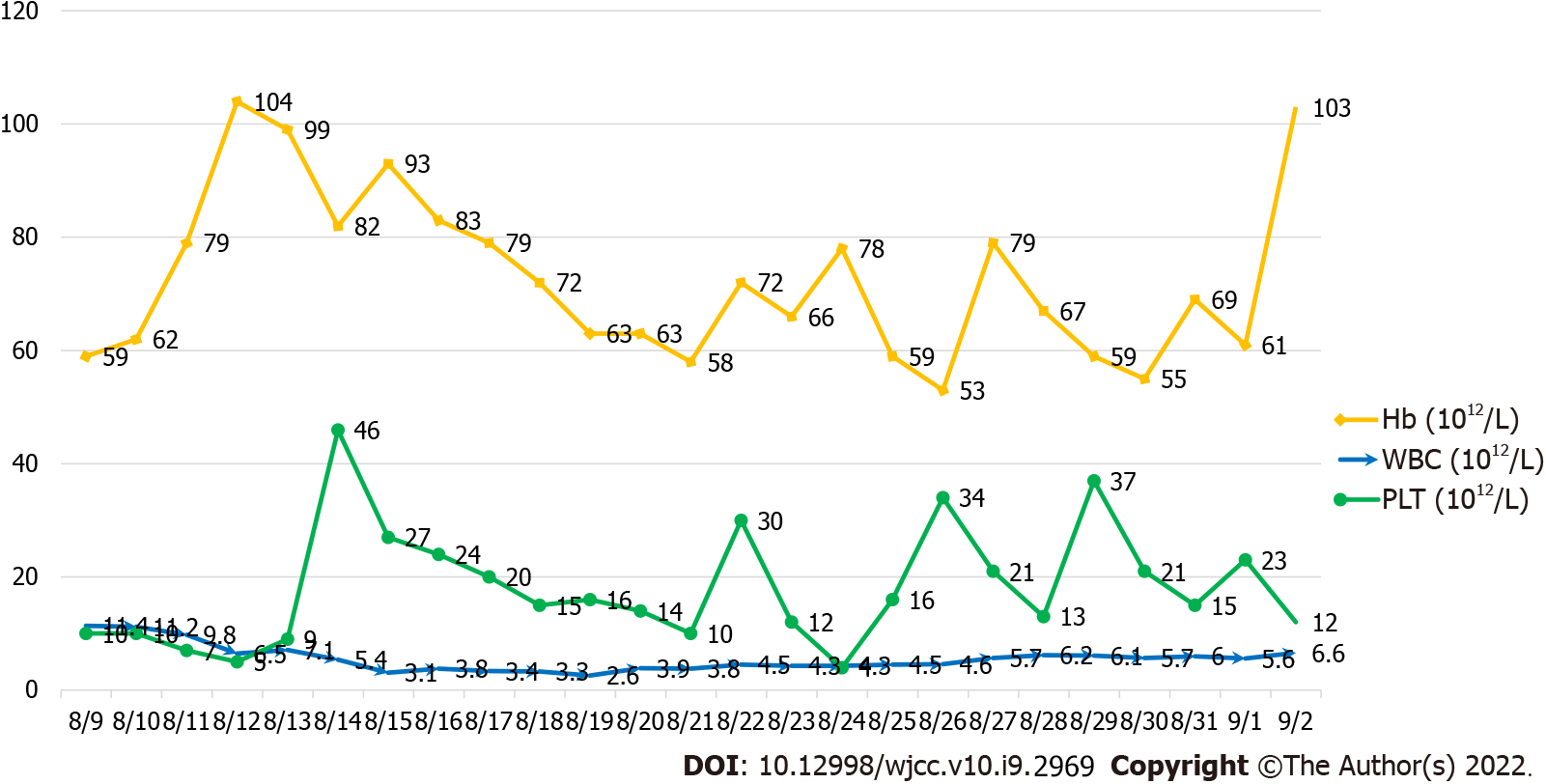

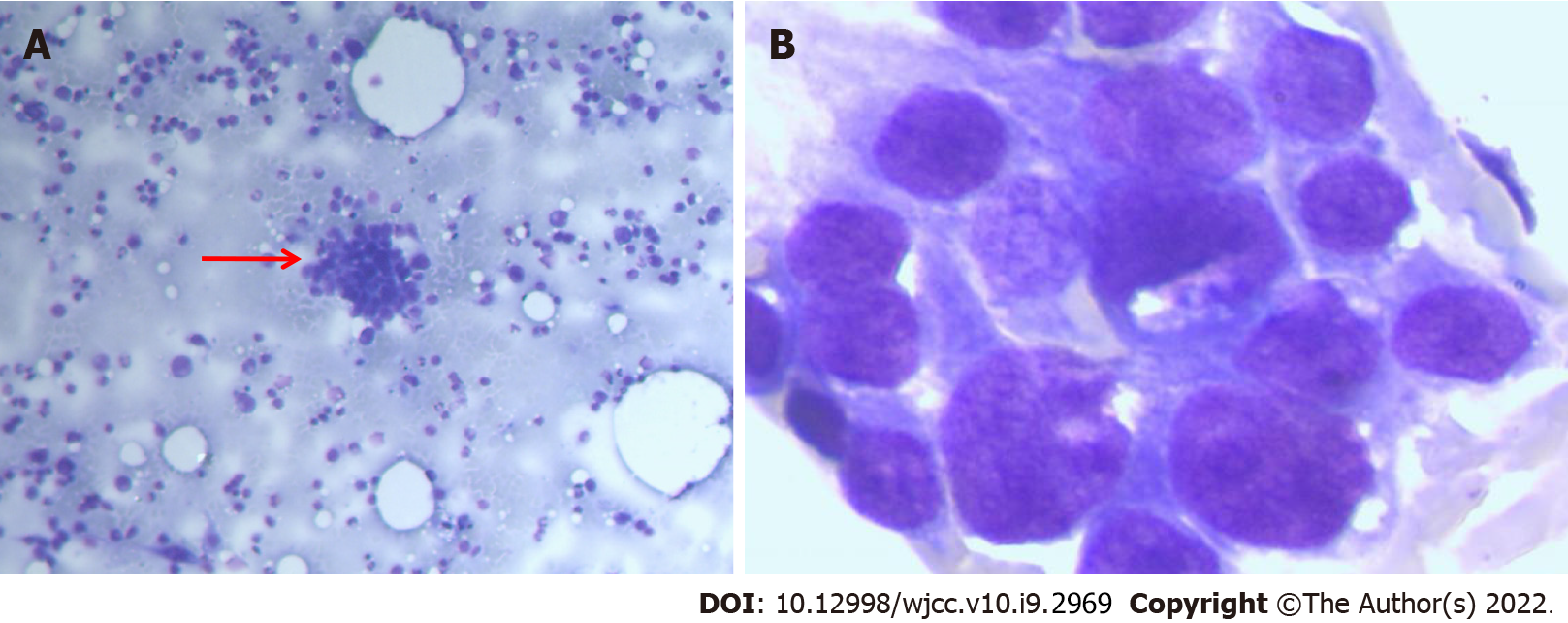

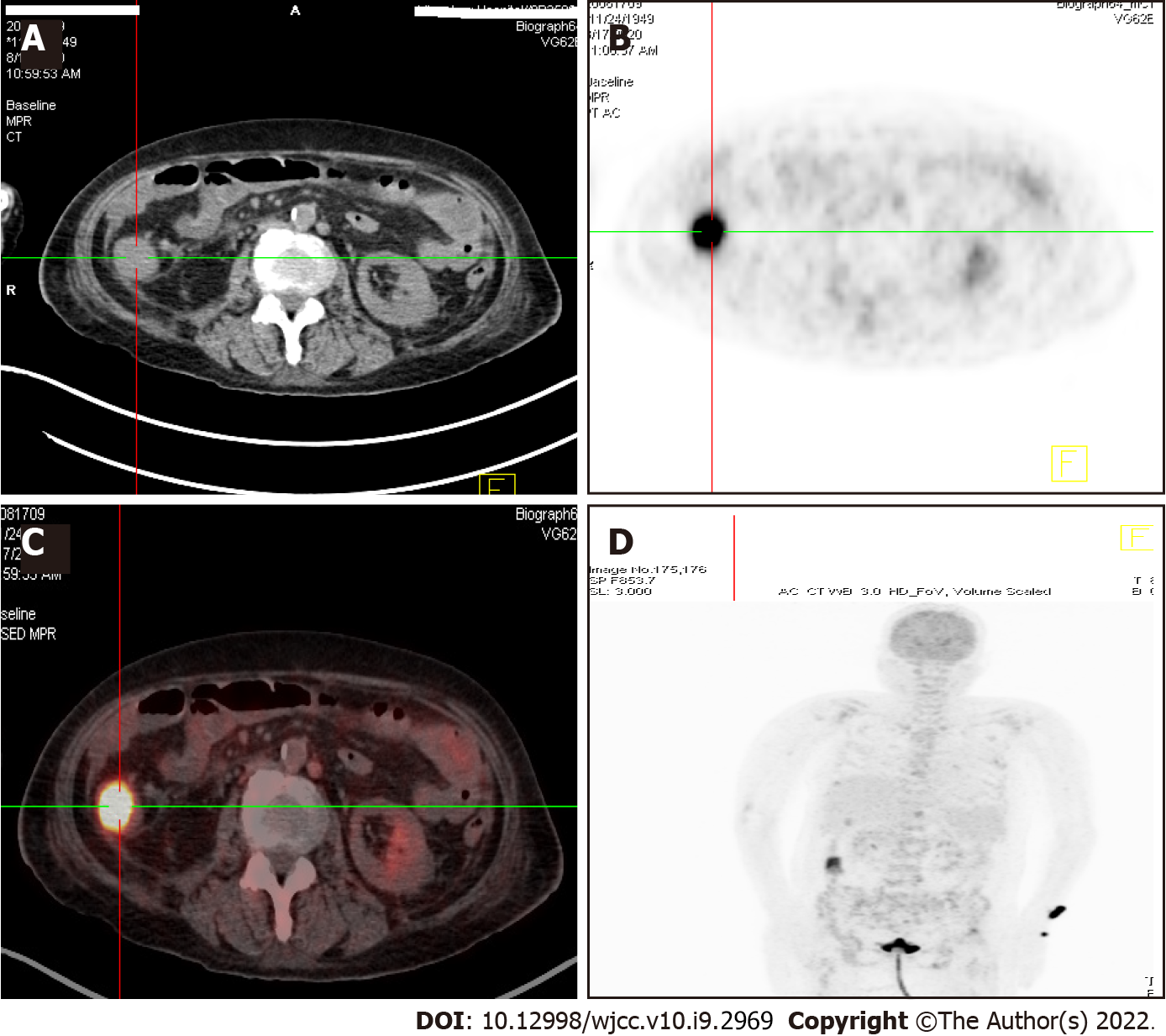

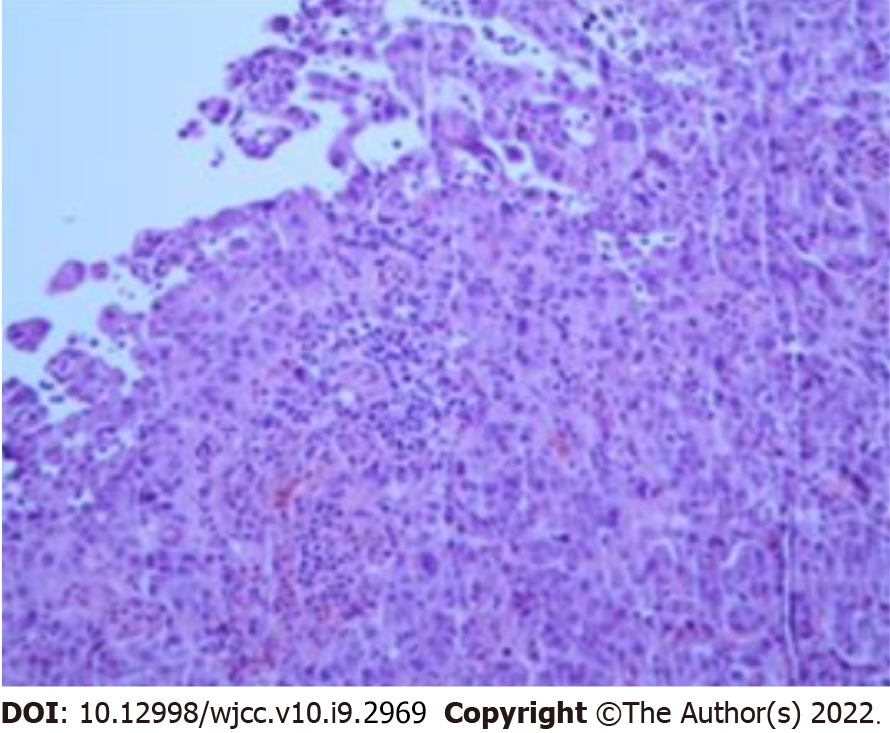

After admission, the patient received anti-inflammatory therapy with 0.5 g meropenem administered intravenously every 6 h, 5 g intravenous human immunoglobulin daily to improve immunity, 4 units of erythrocyte suspension to correct anemia, and 10 units of platelets to increase her PLT count. In addition, insulin micropumps were continuously used to control the patient’s blood glucose levels. The next day, the patient felt cold and experienced chills, her temperature reached 40 °C, and her blood pressure dropped to 85/53 mmHg. The telephone report from the microbiology unit indicated that Escherichia coli (E. coli), Aeromonas hydrophila (A. hydrophila) and Aeromonas caviae (A. caviae) were present in the blood culture. The patient was transferred to the intensive care unit and treated with a 0.5 g meropenem micropump every 6 h and a 50 mg intravenous injection of tetracycline every 12 h to fight infection. Fluid resuscitation was conducted, and vasoactive drugs were administered to maintain blood pressure stability. Following admission to the intensive care unit, the decrease in platelets and Hb was accompanied by a decrease in WBC count (Figure 2). Recombinant human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor was used to elevate the WBC count, and recombinant human PLT growth factor was used to promote PLT production. In addition, erythrocyte suspensions, platelets, and other supportive treatments were administered. One week after antibiotic treatment, the patient’s infection was controlled; her blood pressure and body temperature returned to normal, and the blood culture was negative. Although the WBC count and Hb levels returned to normal, the patient's platelets remained low and could not be corrected with repeated PLT transfusions (Figure 2). A bone marrow biopsy was performed. The bone marrow smear showed many malignant cells (Figure 3). Cancer metastasis to the bone marrow was suspected; thus, a whole-body 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/CT (18F-FDG PET/CT) examination was performed, and the results revealed high metabolic signals in the ascending colon (Figure 4).

Due to thrombocytopenia (TCP) caused by the patient's bone marrow metastasis, surgery and endoscopy were considered contraindicated after a joint discussion among tumor surgery, gastroenterology and intensive care medicine professionals and the patient received conservative medical treatment.

An ascending colon malignant tumor was considered.

The patient received conservative medical treatment.

The tumor progressed, and the patient died 3 wk later. The final autopsy and pathological results showed colon adenocarcinoma (Figure 5).

Bone marrow-metastatic carcinoma results from the migration of medullary tumor cells to the bone marrow through the blood or other body fluids. Bone marrow metastasis can occur in almost all malignant tumors. Lung, breast and prostate cancer patients are most prone to bone marrow metastasis, while this complication is relatively uncommon in colon cancer patients[4-6]. To date, no reports of bone marrow-metastatic colon cancer have been published in mainland China. In addition to the clinical symptoms of primary tumors, bone marrow metastasis is generally characterized by an abnormal blood system. This dysfunction of the blood system mainly manifests as myelosuppression, including decreased PLT counts, Hb levels and WBC counts, and some patients have myeloproliferative manifestations[7,8]. When the patient was admitted, no other obvious clinical symptoms were observed, and her tumor markers were normal. Chest and abdominal CT reports showed no other special abnormalities except mild lung inflammation. This lack of symptoms is consistent with early colon cancer. However, reviewing the abdominal CT scan on admission and subsequent PET/CT results, we found that the right ascending colon wall of the patient was significantly thickened, which was ignored by our clinicians and radiologists. This oversight was the main reason for our initial missed diagnosis. In this case, severe sepsis was the primary manifestation, including high fever, shock, and detection of E. coli, A. hydrophila and A. caviae in the blood culture. Sepsis may have been caused by the tumor destroying the normal mucosal barrier of the intestinal wall, which allowed the intestinal flora to enter the blood; this manifestation has rarely been reported in previous cases. Initially, it was difficult to determine whether the patient’s tricytopenia was the direct result of hematologic disease or caused by bone marrow suppression secondary to severe sepsis. As the patient had no history of hematological diseases, sepsis-related TCP was considered more likely. TCP caused by sepsis is generally related to bone marrow suppression and increased destruction and is often found in patients diagnosed with severe sepsis in the critical care unit, with an incidence of up to 55%[9]. Following infection control, the PLT count gradually returns to normal within 6 d, especially after the application of thrombopoietin[10]. However, when the infection was controlled and the blood culture was negative, the PLT count was difficult to maintain even after repeated PLT transfusions, which is inconsistent with the relief of bone marrow suppression after sepsis control. In addition, when the patient was first admitted to the hospital, her Hb and PLT counts decreased while her WBC count increased, which appeared inconsistent with the myelosuppression changes associated with sepsis. This finding indicated a blood system disease as opposed to sepsis. Therefore, it was necessary to look for other causes, such as blood system diseases or tumor-related TCP. A bone marrow puncture was performed, and the bone marrow smear revealed many malignant cells. Due to the patient's enteric-derived sepsis, enteric-derived tumors were considered. The diagnosis of colon cancer was confirmed by 18F-FDG PET/CT examination because the patient had severe TCP and could not tolerate endoscopy. As the patient's TCP could not be resolved and no exact pathological report could be obtained, surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy could not be performed, the disease progressed, and the patient died.

The incidence of cases of TCP associated with solid tumors is increasing annually, and the underlying mechanism is complex, involving multiple immune and nonimmune factors. Among these factors, bone marrow malignant metastases damage the living microenvironment of hematopoietic stem cells and bone marrow stromal cells, interfere with the normal proliferation, differentiation and physiological functions of blood cells and are an important factor in tumor-related TCP. Studies have shown that 41% of patients with malignant tumors have bone marrow metastasis. Although colon cancer is rarely metastatic, Viehl et al[11] revealed a 38% incidence of bone marrow micrometastasis. Therefore, bone marrow smears have important auxiliary value for diagnosing bone marrow-metastatic cancer. Finding cancer cells on bone marrow smears or in biopsy samples helps diagnose tumors, and some unique cells are even helpful for identifying the primary tumor origin[12,13]. Not all metastatic cancers can be found by a single bone marrow biopsy, and staining the sediment of the puncture or bone marrow biopsy samples is necessary to improve the positive diagnosis rate[14]. The diagnosis of bone marrow metastasis can assist the diagnosis of primary tumors and prognostication, which suggests that it is a useful auxiliary method to diagnose tumors, especially in less developed countries and regions without access to advanced examination equipment, such as PET/CT.

Patients with advanced colon cancer may not have typical clinical symptoms, and bone marrow metastasis is relatively rare. However, when intestinal bacteria-derived sepsis and refractory TCP occur simultaneously, the possibility of secondary bone marrow metastasis from intestinal tumors should be considered. It should not be assumed that the TCP occurred secondary to sepsis, and a bone marrow puncture examination should be performed promptly to identify hematological diseases. Once there is evidence of bone marrow metastasis, digestive endoscopy can be completed as soon as possible, and patients who cannot undergo endoscopy can be examined by systemic PET/CT.

We would like to thank the patient for agreeing to the publication of this article and all doctors and staff who assisted us with this report. We are also very grateful to the translators and indirect tutors.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good):

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Nakaji K, Sun C S-Editor: Chen YL L-Editor: Webster JR P-Editor: Chen YL

| 1. | Yoshino T, Argilés G, Oki E, Martinelli E, Taniguchi H, Arnold D, Mishima S, Li Y, Smruti BK, Ahn JB, Faud I, Chee CE, Yeh KH, Lin PC, Chua C, Hasbullah HH, Lee MA, Sharma A, Sun Y, Curigliano G, Bando H, Lordick F, Yamanaka T, Tabernero J, Baba E, Cervantes A, Ohtsu A, Peters S, Ishioka C, Pentheroudakis G. Pan-Asian adapted ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for the diagnosis treatment and follow-up of patients with localised colon cancer. Ann Oncol. 2021;32:1496-1510. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Alghandour R, Saleh GA, Shokeir FA, Zuhdy M. Metastatic colorectal carcinoma initially diagnosed by bone marrow biopsy: a case report and literature review. J Egypt Natl Canc Inst. 2020;32:30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Chuwa H, Kassam NM, Wambura C, Sherman OA, Surani S. Disseminated Carcinomatosis of Bone Marrow in an African Man with Metastatic Descending Colon Carcinoma. Cureus. 2020;12:e7593. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hanamura F, Shibata Y, Shirakawa T, Kuwayama M, Oda H, Ariyama H, Taguchi K, Esaki T, Baba E. Favorable control of advanced colon adenocarcinoma with severe bone marrow metastasis: A case report. Mol Clin Oncol. 2016;5:579-582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Takeyama H, Sakiyama T, Wakasa T, Kitani K, Inoue K, Kato H, Ueda S, Tsujie M, Fujiwara Y, Yukawa M, Ohta Y, Inoue M. Disseminated carcinomatosis of the bone marrow with disseminated intravascular coagulation as the first symptom of recurrent rectal cancer successfully treated with chemotherapy: A case report and review of the literature. Oncol Lett. 2017;13:4290-4294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Zeeneldin A, Al-Dhaibani N, Saleh YM, Ismail AM, Alzibair Z, Moona MS, Mohamed W. Anorectal Cancer with Bone Marrow and Leptomeningeal Metastases. Case Rep Oncol Med. 2018;2018:9246139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Tyagi R, Singh A, Garg B, Sood N. Beware of Bone Marrow: Incidental Detection and Primary Diagnosis of Solid Tumours in Bone Marrow Aspiration and Biopsies; A Study of 22 Cases. Iran J Pathol. 2018;13:78-84. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Lai GM, Lin JT, Chang CS. Metastatic bone marrow tumors manifested by hematologic disorders: study of thirty-four cases and review of literature. J Anal Oncol. 2014;3:85-90. |

| 9. | Ghimire S, Ravi S, Budhathoki R, Arjyal L, Hamal S, Bista A, Khadka S, Uprety D. Current understanding and future implications of sepsis-induced thrombocytopenia. Eur J Haematol. 2021;106:301-305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Viehl CT, Weixler B, Guller U, Dell-Kuster S, Rosenthal R, Ramser M, Banz V, Langer I, Terracciano L, Sauter G, Oertli D, Zuber M. Presence of bone marrow micro-metastases in stage I-III colon cancer patients is associated with worse disease-free and overall survival. Cancer Med. 2017;6:918-927. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Wu Q, Ren J, Wu X, Wang G, Gu G, Liu S, Wu Y, Hu D, Zhao Y, Li J. Recombinant human thrombopoietin improves platelet counts and reduces platelet transfusion possibility among patients with severe sepsis and thrombocytopenia: a prospective study. J Crit Care. 2014;29:362-366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Chen GL, Zhang RB. Analysis of the role of bone marrow biopsy and smear in the diagnosis of bone marrow metastasis. Zhongguo Aizheng Fangzhi Zazhi. 2016;S2:271-272. |

| 13. | Kucukzeybek BB, Calli AO, Kucukzeybek Y, Bener S, Dere Y, Dirican A, Payzin KB, Ozdemirkiran F, Tarhan MO. The prognostic significance of bone marrow metastases: evaluation of 58 cases. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2014;57:396-399. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Guan JH, Wang XN, Ma K. One-step method of bone marrow aspiration and biopsy applied in diagnosis of the bone marrow metastatic cancer. Zhongguo Shi Yan Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi. 2013;21:1054-1057. [PubMed] |