Published online Mar 26, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i9.2961

Peer-review started: November 14, 2021

First decision: December 10, 2021

Revised: December 22, 2021

Accepted: January 29, 2022

Article in press: January 29, 2022

Published online: March 26, 2022

Processing time: 128 Days and 9.5 Hours

Struma ovarii is a rare specific ovarian tumor. It is a highly differentiated monodermal teratoma with a malignant transformation rate as low as 5%. Thus, malignant transformation and metastasis are extremely rare. The clinical manifestations of this disease are not typical and are easily misdiagnosed.

A 55-year-old female patient had a history of pain in the right hepatic region for approximately 1 year. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging showed a solid cystic mass in the right adnexal region and a solid mass in the right retroperitoneum. The patient underwent surgical resection, and the combined morphological and immunohistochemical results led to the final diagnosis of right struma ovarii with papillary carcinoma and right retroperitoneal lymph node metastasis.

Malignant struma ovarii with distant metastasis is extremely rare, and the clinical manifestations of this disease are nonspecific. Accurate preoperative diagnoses are difficult to obtain, and pathological examination is the gold standard for diagnosing this disease.

Core Tip: Malignant struma ovarii (MSO) with biologically malignant behavior is an extremely rare disease. The rarity of MSO and the nonspecific clinical presentation make it very difficult to diagnose preoperatively. We report a case of MSO, for which we analyzed a combination of pathological and immunohistochemical findings, to improve the understanding of this disease. A clear preoperative diagnosis of MSO can be particularly helpful for doctors in formulating the best treatment plan, allowing patients to avoid unnecessary treatments to the greatest extent possible.

- Citation: Xiao W, Zhou JR, Chen D. Malignant struma ovarii with papillary carcinoma combined with retroperitoneal lymph node metastasis: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(9): 2961-2968

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i9/2961.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i9.2961

Struma ovarii is a rare and highly differentiated monodermal tumor that contains more than 50% thyroid tissue and accounts for 2%-3% of ovarian teratomas[2,3]. This tumor is usually benign, and malignant transformation and metastasis are extremely rare, with malignant transformation occurring in approximately 5% of cases[4,6]. The disease can affect females of all ages but is most common in patients of childbearing age[10]. The clinical manifestations of this disease are not specific and are mostly characterized by abdominal symptoms, such as abdominal pain and irregular vaginal bleeding[4]. Malignant struma ovarii (MSO) is very difficult to diagnose preoperatively due to the lack of specific imaging manifestations, so histopathology is necessary to confirm the diagnosis.

The purpose of our report is to present a case of MSO and analyze its clinical, pathological, and imaging features to improve the understanding of this disease and to provide a reference for the preoperative diagnosis and treatment selection of this disease.

A 55-year-old female patient was admitted to the hospital with pain in the liver area lasting for more than 1 year.

The patient presented with persistent pain in the liver area with a burning sensation on the skin for 1 year, and one instance of a small amount of bloody vaginal secretion was found six months ago.

The patient has had hypertension for more than 5 years.

Her mother died of stomach cancer, and her father died of emphysema.

A lymph node measuring approximately 0.6 cm × 0.6 cm was palpated in the right inguinal region of the patient. There was an irregular active mass palpable on the left anterior side of the uterus, approximately 8 cm × 6 cm × 6 cm in size.

Her blood pressure was elevated, with a maximum systolic pressure of 180 mmHg, and HPV type 39/53 (+) was detected. Her serum thyroglobulin (TG) concentration was > 500 ng/mL, which decreased to 39.13 ng/mL after gynecological surgery (normal range: 3.50-77.00 ng/mL). The other laboratory examinations (including routine blood and urine tests, coagulation function tests, liver and kidney function tests, and evaluations of tumor marker levels) were normal, with CA125 (-).

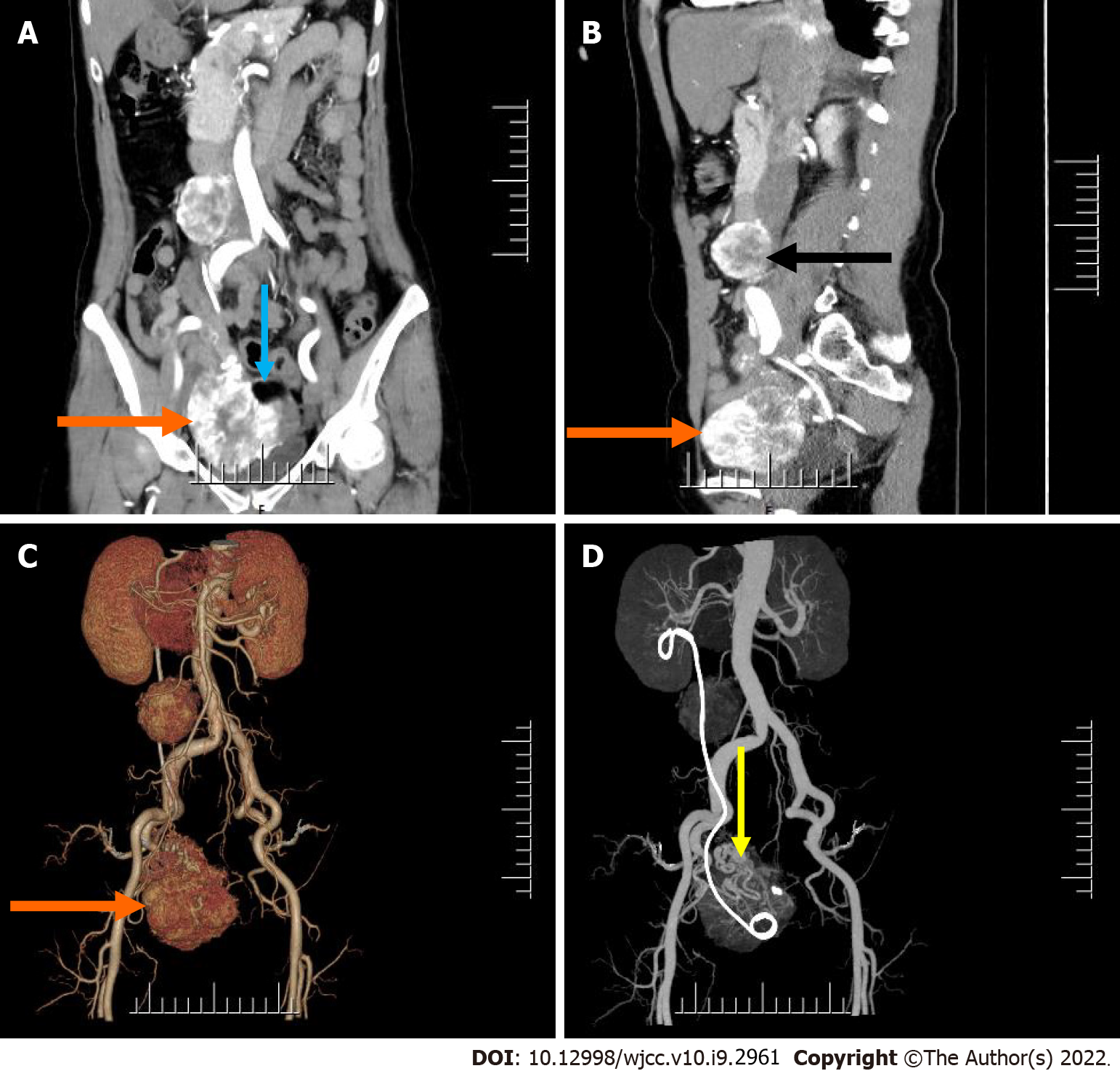

Computed tomography (CT) examination showed an irregular mass with mixed density in the right adnexal region, measuring approximately 8.7 cm × 7.6 cm × 6.5 cm, with a clear boundary (Figure 1). A contrast-enhanced scan showed obvious heterogeneous enhancement, and multiple thickened and tortuous vessel shadows were found in the lesion, which was mainly supplied by the right reproductive artery (Figure 1C and D). In addition, there was a fat density shadow in the left portion of the mass, which was not enhanced on the contrast-enhanced scan (Figure 1A). In the right retroperitoneum, there was a rounded mass with soft tissue density that was approximately 4.3 cm × 3.2 cm × 4.6 cm in size, with a well-defined boundary (Figure 1). The mass located to the right in front of the inferior vena cava was closely associated with the inferior vena cava, which was mildly compressed. Additionally, a contrast-enhanced scan showed heterogeneous marked enhancement (Figure 1A and B).

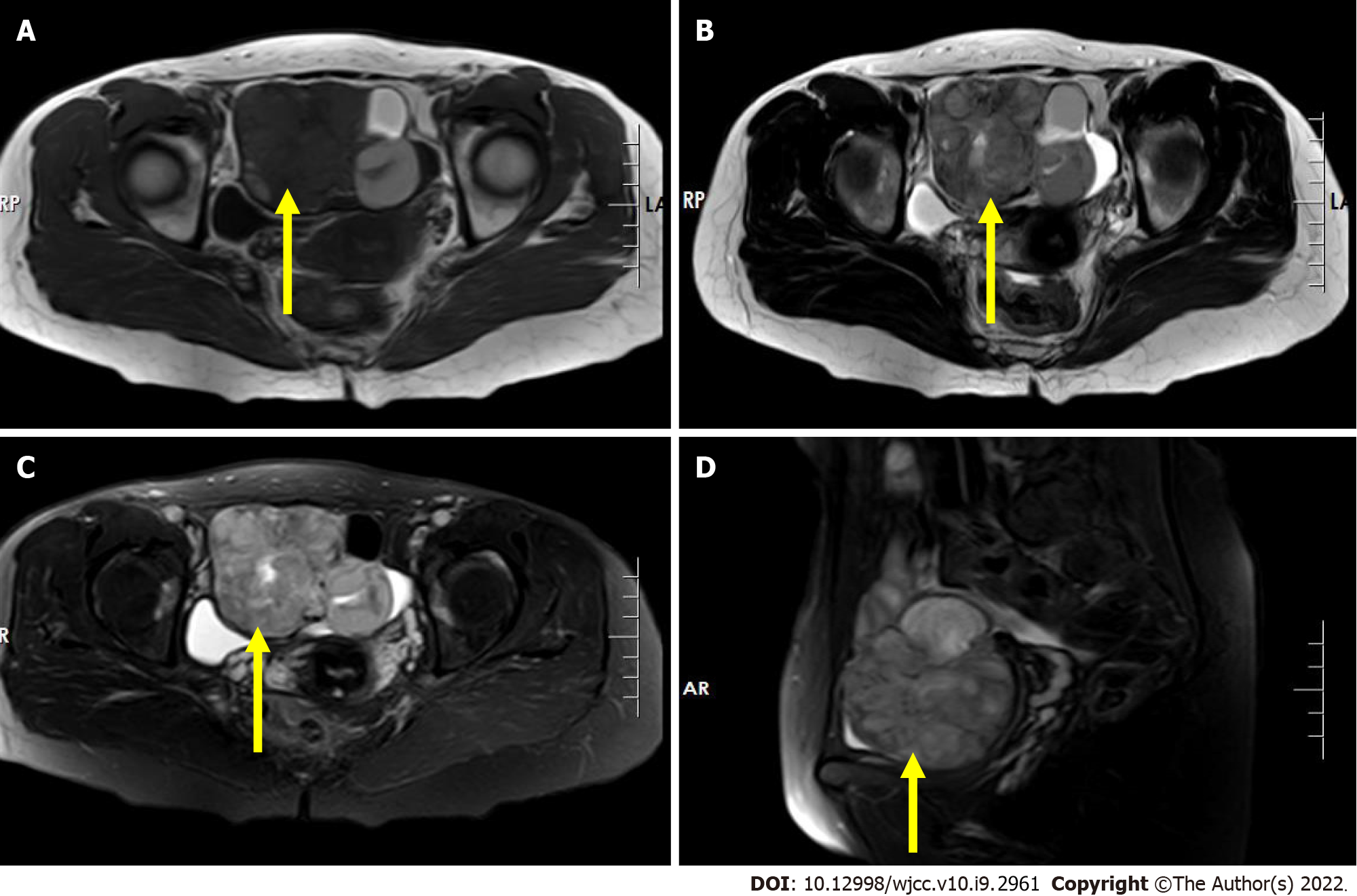

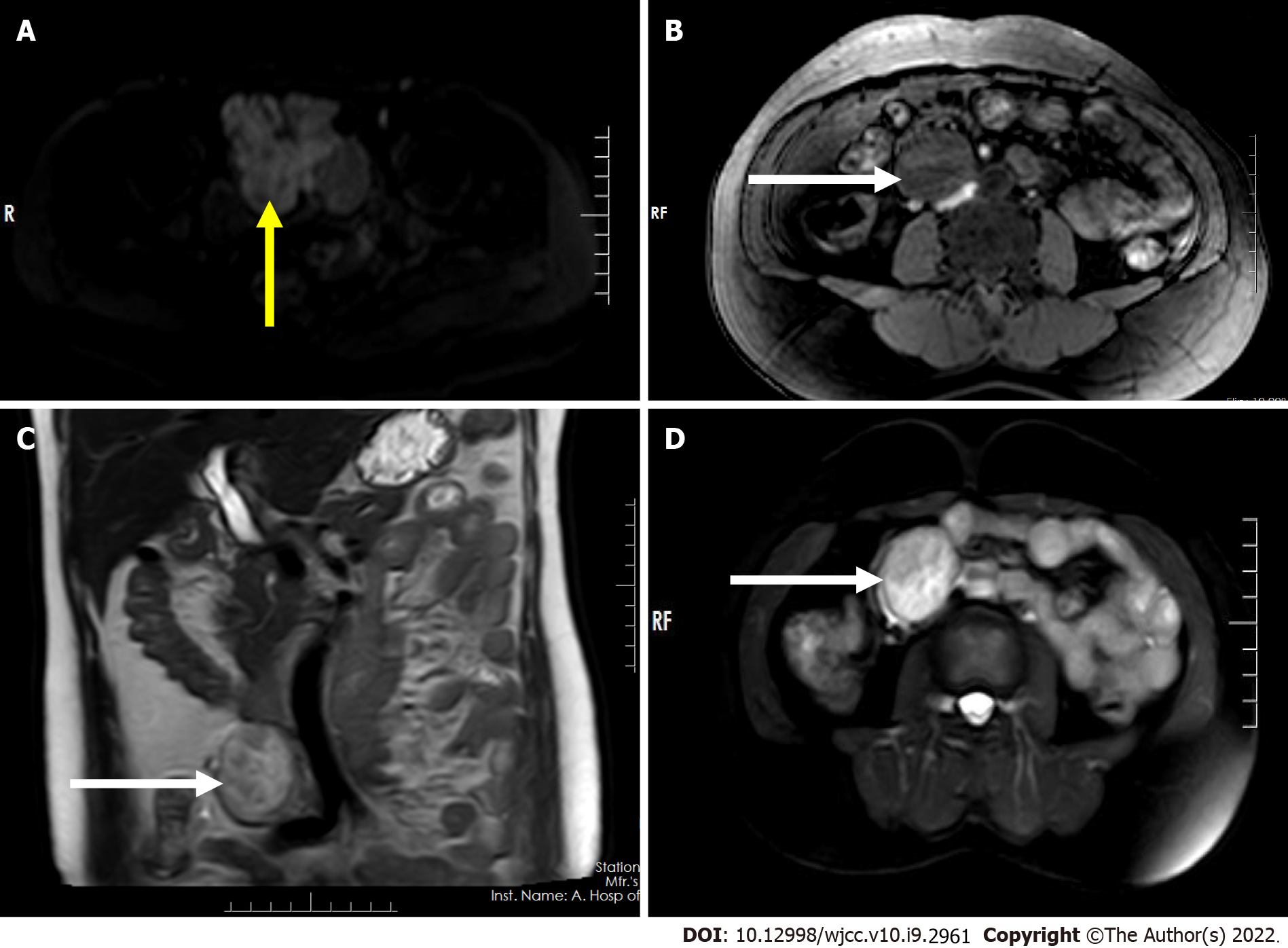

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed an irregular mass with mixed signal in the right adnexal region with an iso/hypointense signal on T1-weighted imaging (T1WI) (Figure 2A), a slightly high heterogeneous signal intensity on T2-weighted imaging (T2WI) and short tau inversion recovery (STIR) imaging (Figure 2B-D), hyperintense signal on diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) (Figure 3A), and further hyperintense signal at the edge of the lesion (each sequence), suggesting the possibility of hemorrhage within the lesion. The mass in the right retroperitoneum was characterized by low signal intensity on T1WI (Figure 3B), inhomogeneous slightly high/high signal intensity on T2WI (Figure 3C), and inhomogeneous high signal intensity on STIR imaging (Figure 3D).

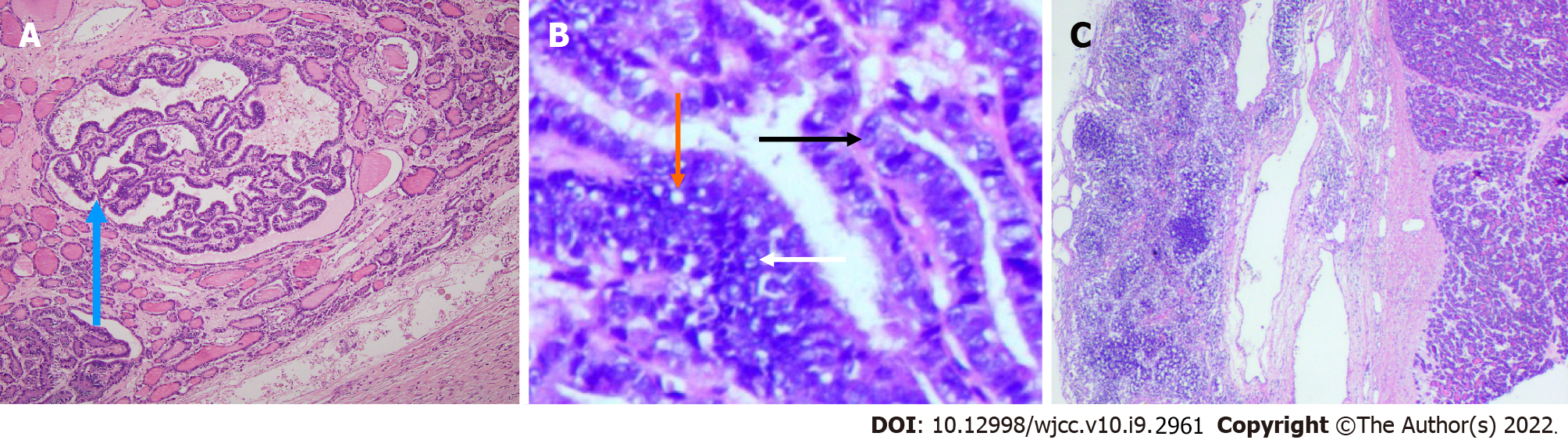

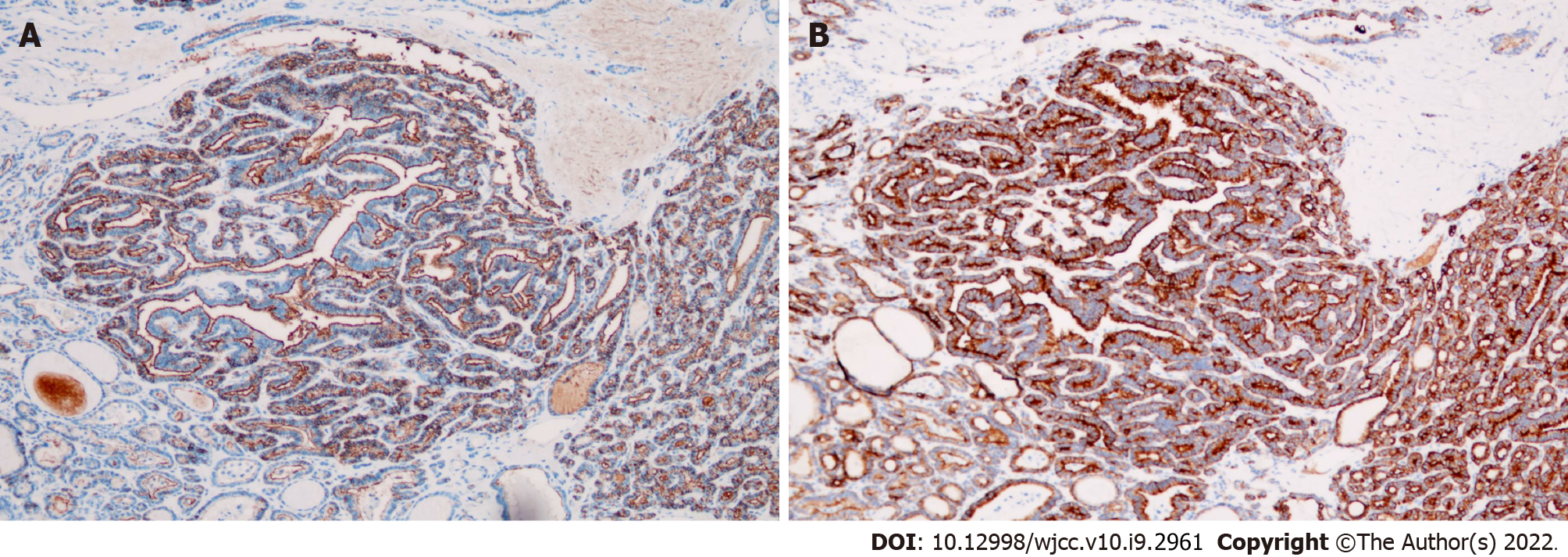

Surgically resected specimens revealed thyroid-like tissue with local papillary structure and necrosis in the tumor of the right adnexa (Figure 4A and B). Immunohistochemistry showed CK19(+), TG(+), TTF-1(+), galectin-3(+), HBME-1(+), and CD56 (partially absent) in the lesion (Figure 5). Thyroid-like tissue with localized papillary structures was identified within the tumor in the right retroperitoneum; this lesion was closely associated with the retroperitoneal lymph nodes (Figure 4C).

MSO with papillary carcinoma in the right adnexa and right-sided retroperitoneal lymph node metastasis.

After a series of relevant examinations, the patient underwent selective vascular embolization (right internal iliac artery and ovarian artery) because of the rich blood supply to the tumor in the pelvis, followed by resection of the right pelvic tumor and right retroperitoneal tumor+ bilateral adnexal resection + pelvic lavage under general anesthesia. During the surgery, the boundary between the pelvic mass and right ovary was not clear, the right fallopian tube was not involved, and the mass was mainly supplied by the right ovarian artery. The right retroperitoneal mass had an intact capsule, which was adjacent to the inferior vena cava but was clearly demarcated from the inferior vena cava and ureter. Hysterectomy and pelvic lymph node dissection were not performed. Postoperatively, routine anti-infective treatment was provided.

The patient recovered well postoperatively with significant relief of her abdominal pain. She was followed up five months postoperatively, and no signs of recurrence were seen on CT.

Struma ovarii is a rare type of mature teratoma with monodermal high specificity. It contains at least 50% thyroid tissue and is a germ cell tumor of the ovary, accounting for 2%-3% of ovarian teratomas[2-3,6]. The disease is mostly benign and unilateral, and malignant transformation and metastasis are extremely rare. The malignant transformation rate is as low as 5%, and the most common malignancies are papillary carcinoma (approximately 70%) and follicular carcinoma (approximately 30%)[4,6,10-11]. MSO metastasizes in approximately 5%-23% of cases[2,10], mainly leading to lymphatic and blood metastasis and peritoneal and omental metastasis, but metastases have also been seen in the pelvis, liver, lung, etc.[1,2].

Struma ovarii was first described by Von Kalden in 1895[2,3]. It can occur in women of any age. However, this tumor is more common in women aged 4-60 years and is less common in postmenopausal women[10]. The clinical manifestations of the disease are nonspecific and usually include abdominal symptoms, such as abdominal pain, abdominal distention, abdominal mass, irregular vaginal bleeding, and infertility. Some patients also have hyperthyroidism, a small amount of ascites and other symptoms[4,6]. Additionally, some patients can present with elevated ovarian tumor marker CA125[3,6], but this index was not elevated in the patient in this report.

Pathologically, the solid component of MSO includes thyroid tissue and abundant interstitial vessels. Histological malignancy is not equivalent to biological malignancy, and biological malignancy can be diagnosed by any one of the following criteria: (1) Extraovarian metastasis; (2) Tumor invasion on the surface of the serous membrane of the ovary; and (3) Recurrence after the initial surgery[5]. This patient met the first two conditions, so this case was judged to be biologically malignant.

Patients with both MSO and thyroid cancer are generally classified into three conditions: (1) Metastasis of thyroid cancer to the ovary; (2) Metastasis of MSO to the thyroid; and (3) Concurrent occurrence of thyroid cancer and MSO[11]. This patient had a solid cystic mass with mixed echogenicity measuring approximately 0.6 cm x 0.5 cm x 0.3 cm in size on an ultrasound examination of the left lobe of the thyroid gland. This patient underwent single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) thyroid imaging, which showed no abnormalities in thyroid morphology, density, size, or function based on 99mTc uptake. Elevated TG was detected before abdominal surgery, and no increase in this index was seen postoperatively. Unfortunately, the patient has not yet undergone total thyroidectomy, so it is unknown whether the patient suffers from both diseases. However, based on the results of the above supplementary examination, it is reasonable to assume that the patient did not have thyroid disease. Some scholars believe that the presence of a teratoma and normal thyroid epithelial tissue is highly suggestive of primary MSO rather than a lesion that is the source of the thyroid cancer metastasi[6,8]. Therefore, we considered the patient's MSO to be the primary focus.

Due to the rarity of MSO, there are few relevant reports on this disease, most of which are case reports, and no definitive optimal uniform treatment protocol is currently available. The management course of abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy with omentectomy, with or without hysterectomy, and unilateral adnexal resection is supported by most scholars only for young patients without metastases to preserve fertility to the greatest extent possible. Extraovarian tumor extension is considered an indication for total thyroidectomy and adjuvant treatment, such as radioactive iodine [I]-131 ablation, in postoperative patients[6,10,12,13]. The greatest controversy has been whether to routinely administer postoperative adjuvant therapy to patients without evidence of metastasis. Some studies have suggested that the recurrence rate is lower in patients who received routine adjuvant therapy after surgery than in patients who only underwent surgery, but other studies have suggested that there are no significant differences in the recurrence rate and prognosis of patients despite the use of adjuvant therapy after surgery[6].

The clinical course of MSO is long, and the prognosis is generally good. The presence of metastases does not cause treatment dilemmas, with most patients achieving a long survival duration after treatment. However, the presence of the histologic subtype of atypical papillary thyroid carcinoma in the tumor is an independent predictor of poor prognosis or treatment failure[11]. Additionally, some patients may develop recurrence and require close long-term follow-up. TG is a glycoprotein unique to thyroid tissue, and some patients with MSO have elevated serum TG levels, which are useful for monitoring tumor recurrence and tumor regression after treatment[1,5].

MSO has a similar imaging presentation to struma ovarii, does not have obvious specific imaging findings, and is more common unilaterally[4]. The most common CT presentations are cystic masses or predominantly cystic lobulated cystic-solid masses, which can include single or multiple cysts with segregation of the cystic portion and solid components that represent thyroid tissue. The mass is typically characterized by a well-defined, highly attenuated area and calcifications[8].

On MRI, MSO shows a solid cystic mass of uterine adnexal origin with well-defined borders and cystic cavities of different sizes. Each cystic cavity has a different signal due to different TG contents. Most of these cavities present a high signal on T1WI, and an extremely low signal on T2WI is characteristic of these cavities. DWI shows a high signal when the cystic cavity has a high protein content. On contrast-enhanced scans, the solid components of the tumor and cystic wall and the separation between these tissues showed progressive and distinct enhancement[8].

In general, MSO needs to be differentiated from the following tumors: (1) Cystadenocarcinoma: the solid component mostly shows wall nodules or nodular soft tissue protruding into the cystic cavity, a large amount of ascites, and malignant signs such as lymph node metastasis; (2) Cystadenoma: The cyst wall and septum are thin and smooth and without obvious enhancement on contrast-enhanced scans; and (3) Infectious lesions: abdominal pain, fever, and elevated white blood cells are common, and the lesions are mostly adherent to the surrounding tissue structures.

A clear preoperative diagnosis of MSO can be particularly helpful for doctors in formulating the best treatment plan, allowing patients to avoid unnecessary treatments, such as hysterectomy, and preserving fertility to the greatest extent possible in young patients without metastasis. The patient in this case report presented with abdominal pain. CT and MRI demonstrated a solid cystic mass in the pelvis and a right retroperitoneal mass; the preoperative examination revealed the absence of tumor markers [CA125(-)]. Thus, the preoperative misdiagnosis was a malignant right ovarian teratoma combined with hemorrhage and right retroperitoneal neurogenic tumor, without preoperative examination of the thyroid.

In summary, cases of MSO with distant metastasis are extremely rare, and the clinical manifestations of this disease are nonspecific. Thus, it is difficult to obtain an accurate diagnosis preoperatively. Preoperative CT, MRI and thyroid function examinations, combined with the patients’ clinical manifestations, can help improve the accuracy of the preoperative diagnosis and provide great assistance in developing an appropriate treatment plan.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Radiology, nuclear medicine and medical imaging

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Rahimi-Movaghar E, Shariati MBH, Yoshida H S-Editor: Xing YX L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Chan SW, Farrell KE. Metastatic thyroid carcinoma in the presence of struma ovarii. Med J Aust. 2001;175:373-374. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Dardik RB, Dardik M, Westra W, Montz FJ. Malignant struma ovarii: two case reports and a review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol. 1999;73:447-451. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Marcy PY, Thariat J, Benisvy D, Azuar P. Lethal, malignant, metastatic struma ovarii. Thyroid. 2010;20:1037-1040. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Robboy SJ, Shaco-Levy R, Peng RY, Snyder MJ, Donahue J, Bentley RC, Bean S, Krigman HR, Roth LM, Young RH. Malignant struma ovarii: an analysis of 88 cases, including 27 with extraovarian spread. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2009;28:405-422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Shaco-Levy R, Bean SM, Bentley RC, Robboy SJ. Natural history of biologically malignant struma ovarii: analysis of 27 cases with extraovarian spread. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2010;29:212-227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Tzelepis EG, Barengolts E, Garzon S, Shulan J, Eisenberg Y. Unusual Case of Malignant Struma Ovarii and Cervical Thyroid Cancer Preceded by Ovarian Teratoma: Case Report and Review of the Literature. Case Rep Endocrinol. 2019;2019:7964126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Thomas JJ, Maheshwari S, Alwaheedy M. Papillary Carcinoma in Struma Ovarii: A Radiological Dilemma. Cureus. 2021;13:e17360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ikeuchi T, Koyama T, Tamai K, Fujimoto K, Mikami Y, Konishi I, Togashi K. CT and MR features of struma ovarii. Abdom Imaging. 2012;37:904-910. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sah S, McCluggage WG. Ovarian Combined Brenner Tumor, Mucinous Cystadenoma and Struma Ovarii: First Report of a Rare Combination. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2019;38:576-580. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Gonet A, Ślusarczyk R, Gąsior-Perczak D, Kowalik A, Kopczyński J, Kowalska A. Papillary Thyroid Cancer in a Struma Ovarii in a 17-Year-Old Nulliparous Patient: A case Report. Diagnostics (Basel). 2020;10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ayhan S, Kilic F, Ersak B, Aytekin O, Akar S, Turkmen O, Akgul G, Toyran A, Turan T, Kimyon Comert G. Malignant struma ovarii: From case to analysis. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2021;47:3339-3351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Zhang X, Axiotis C. Thyroid-type carcinoma of struma ovarii. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134:786-791. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Marti JL, Clark VE, Harper H, Chhieng DC, Sosa JA, Roman SA. Optimal surgical management of well-differentiated thyroid cancer arising in struma ovarii: a series of 4 patients and a review of 53 reported cases. Thyroid. 2012;22:400-406. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |