Published online Mar 26, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i9.2923

Peer-review started: October 7, 2021

First decision: December 17, 2021

Revised: December 25, 2021

Accepted: February 20, 2022

Article in press: February 20, 2022

Published online: March 26, 2022

Processing time: 166 Days and 6.9 Hours

Acute stent thrombosis (AST) is a serious complication of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). The causes of AST include the use of stents of inappropriate diameters, multiple overlapping stents, or excessively long stents; incomplete stent expansion; poor stent adhesion; incomplete coverage of dissection; formation of thrombosis or intramural hematomas; vascular injury secondary to intraoperative mechanical manipulation; insufficient dose administration of postoperative antiplatelet medications; and resistance to antiplatelet drugs. Cases of AST secondary to coronary artery spasms are rare, with only a few reports in the literature.

A 55-year-old man was admitted to the hospital with a chief complaint of back pain for 2 d. He was diagnosed with coronary heart disease and acute myocardial infarction (AMI) based on electrocardiography results and creatinine kinase myocardial band, troponin I, and troponin T levels. A 2.5 mm × 33.0 mm drug-eluting stent was inserted into the occluded portion of the right coronary artery. Aspirin, clopidogrel, and atorvastatin were started. Six days later, the patient developed AST after taking a bath in the morning. Repeat coronary angiography showed occlusion of the proximal stent, and intravascular ultrasound showed severe coronary artery spasms. The patient’s AST was thought to be caused by coronary artery spasms and treated with percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty. Postoperatively, he was administered diltiazem to inhibit coronary artery spasms and prevent future episodes of AST. He survived and reported no discomfort at the 2-mo follow-up after the operation and initiation of drug treatment.

Coronary spasms can cause both AMI and AST. For patients who exhibit coronary spasms during PCI, diltiazem administration could reduce spasms and prevent future AST.

Core Tip: Acute stent thrombosis (AST) is a serious complication of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). The causes of AST include the use of stents of inappropriate diameters, multiple overlapping stents, or excessively long stents; incomplete stent expansion; poor stent adhesion; incomplete coverage of dissection; formation of thrombosis or intramural hematomas; vascular injury secondary to intraoperative mechanical manipulation; insufficient dose administration of postoperative antiplatelet medications; and resistance to antiplatelet drugs. Cases of AST secondary to coronary artery spasms are rare. We report a case of AST in a 52-year-old man possibly caused by a coronary artery spasm. Coronary spasms can cause both AMI and AST. For patients with coronary spasms during PCI, diltiazem administration could reduce spasms and prevent future AST.

- Citation: Meng LP, Wang P, Peng F. Acute coronary artery stent thrombosis caused by a spasm: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(9): 2923-2930

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i9/2923.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i9.2923

Acute stent thrombosis (AST) is a serious complication of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). When bare metal stents were often used, the incidence rate of AST was approximately 1.2%[1]. However, in recent years, because of the widespread use of drug-eluting stents and continuous advancements in the treatment of complex lesions, the incidence rate of AST has been increasing[2]. Currently, the known causes of AST include the use of stents of inappropriate diameters, multiple overlapping stents, or excessively long stents; incomplete coverage of dissection; incomplete stent expansion; poor stent adhesion; formation of thrombosis or intramural hematomas; vascular injury secondary to intraoperative mechanical manipulation; insufficient dose administration of postoperative antiplatelet medications; and resistance to antiplatelet drugs[3,4]. However, the occurrence of AST secondary to coronary artery spasms is rare, with only a few cases reported in the literature[5]. Here, we report a case of AST possibly caused by a coronary artery spasm.

A 55-year-old man was admitted to the hospital with a chief complaint of back pain for 2 d.

Two days before admission, the patient developed non-radiating back pain, nausea, discomfort, fatigue, and an impending sense of doom. He reported no shortness of breath or vomiting. His symptoms lasted for 6-7 h and improved afterwards. He did not seek medical consultation until the day of admission.

The patient had hypertension for 3 years and was on irbesartan 80 mg qd.

The patient reported no history of smoking, diabetes, or malignancy.

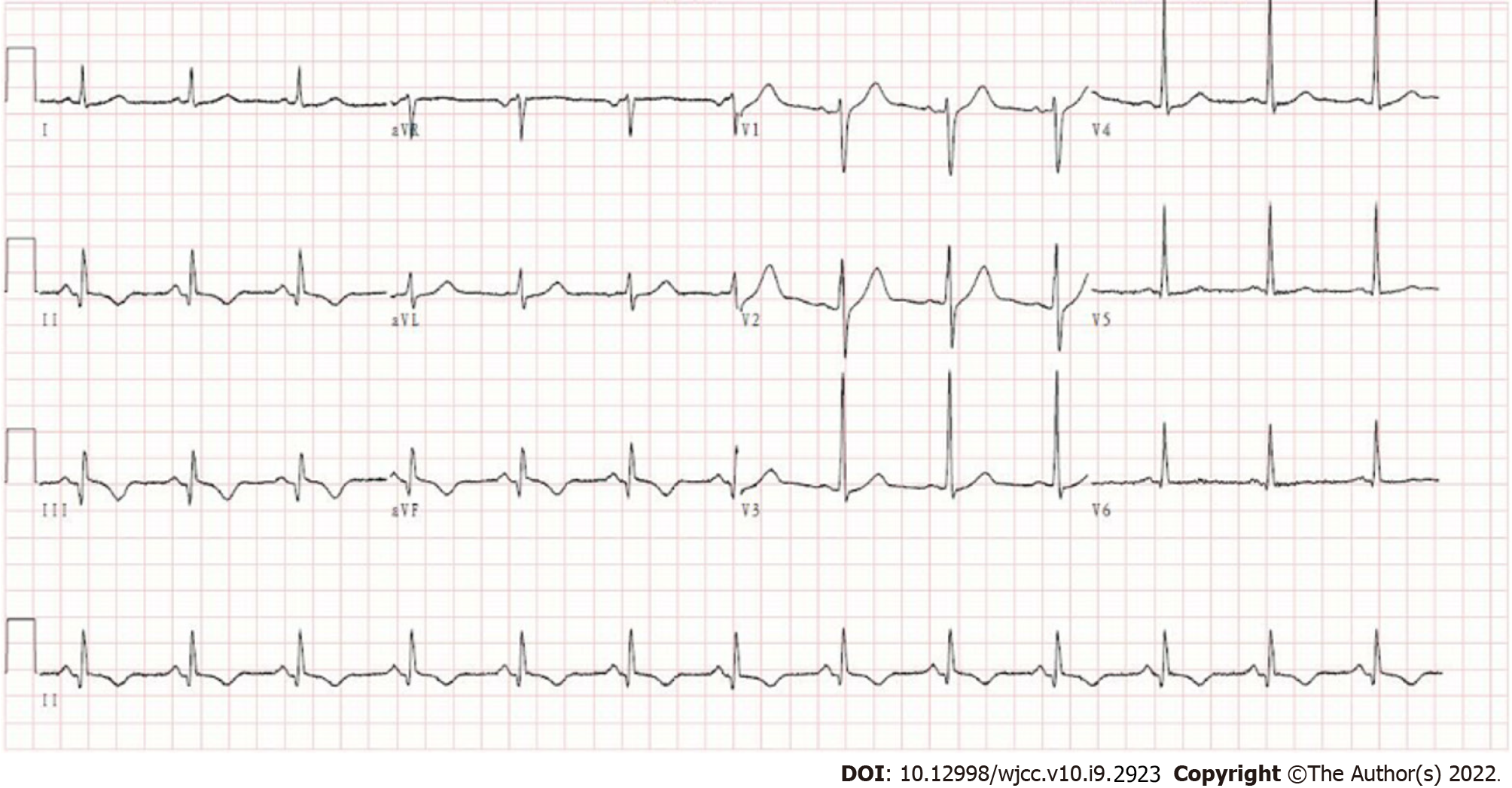

Physical examination revealed no abnormalities.

At the hospital, the electrocardiogram showed a sinus rhythm; possible inferior myocardial infarction in leads II, III, and aVF; and mild ST-segment depression. The patient was administered with ticagrelor 180 mg, aspirin 300 mg, and atorvastatin 20 mg before emergency department transfer. The repeat electrocardiogram showed an abnormal sinus rhythm; Q wave; and II, III, aVF T-wave changes (Figure 1). Blood examination revealed a troponin level of 23.85 ng/mL and a creatine kinase myocardial band isoenzyme level of 90.2 U/L. The patient was admitted to the critical care unit for acute inferior myocardial infarction.

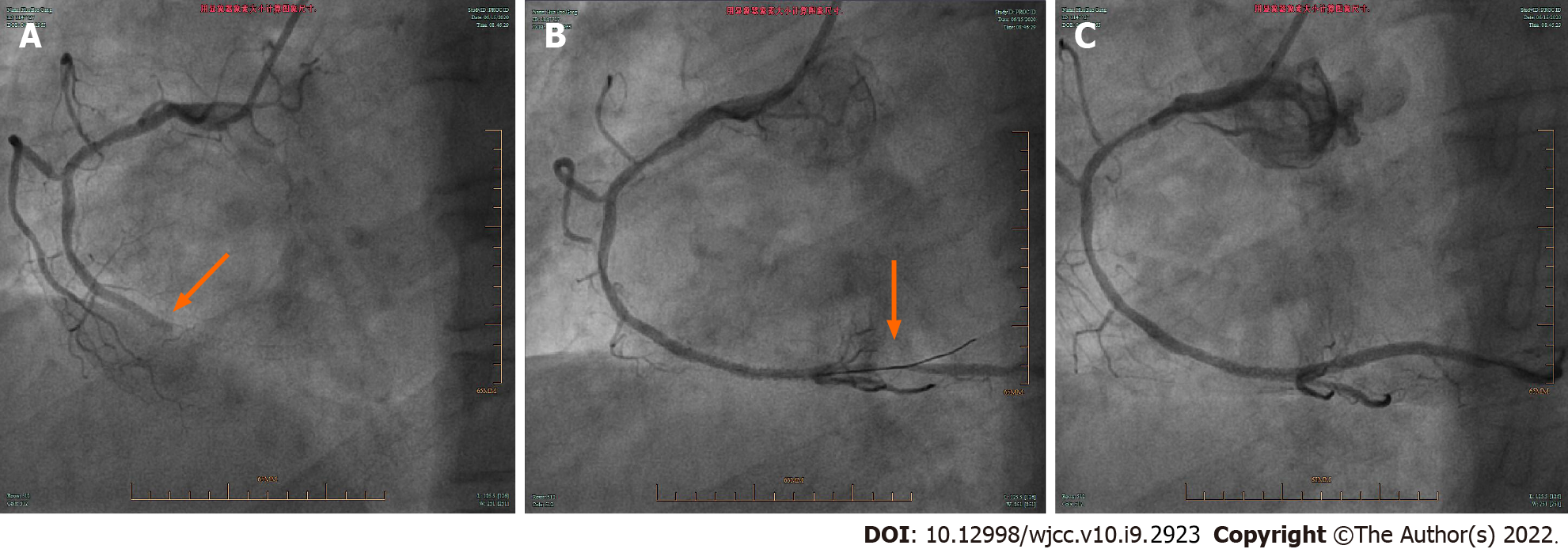

Six days later, the patient’s troponin levels returned to normal. Coronary angiography showed no left main coronary or left circumflex artery stenosis, 60% stenosis in the proximal left anterior descending artery, 60%-70% stenosis in the proximal right coronary artery (RCA), and complete occlusion of the middle parts of the RCA (Figure 2A).

Balloon angioplasty was performed with a 2.0 mm × 15.0 mm balloon in the middle part of the RCA. Repeat angiography showed 90% stenosis in both the middle and distal parts of the RCA (Figure 2B). Distal RCA stenosis resolved after injecting 2 mL of nitroglycerin (Figure 2C). A 2.5 mm × 33.0 mm drug-eluting stent was then inserted into the middle part of the RCA. A Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) flow grade of 3 was documented postoperatively (Figure 2D).

Final diagnoses of coronary heart disease, acute myocardial infarction (AMI), and AST were made.

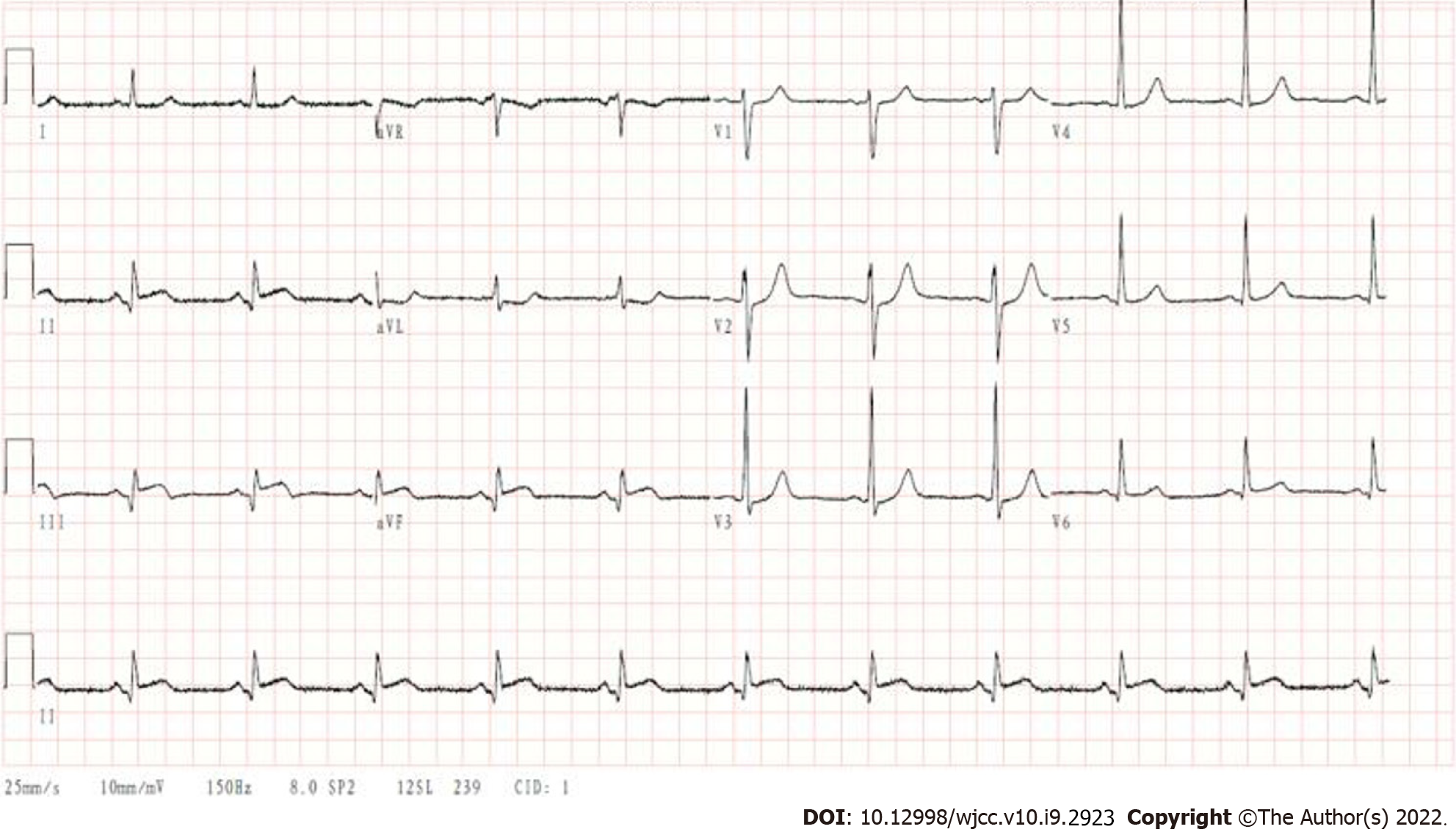

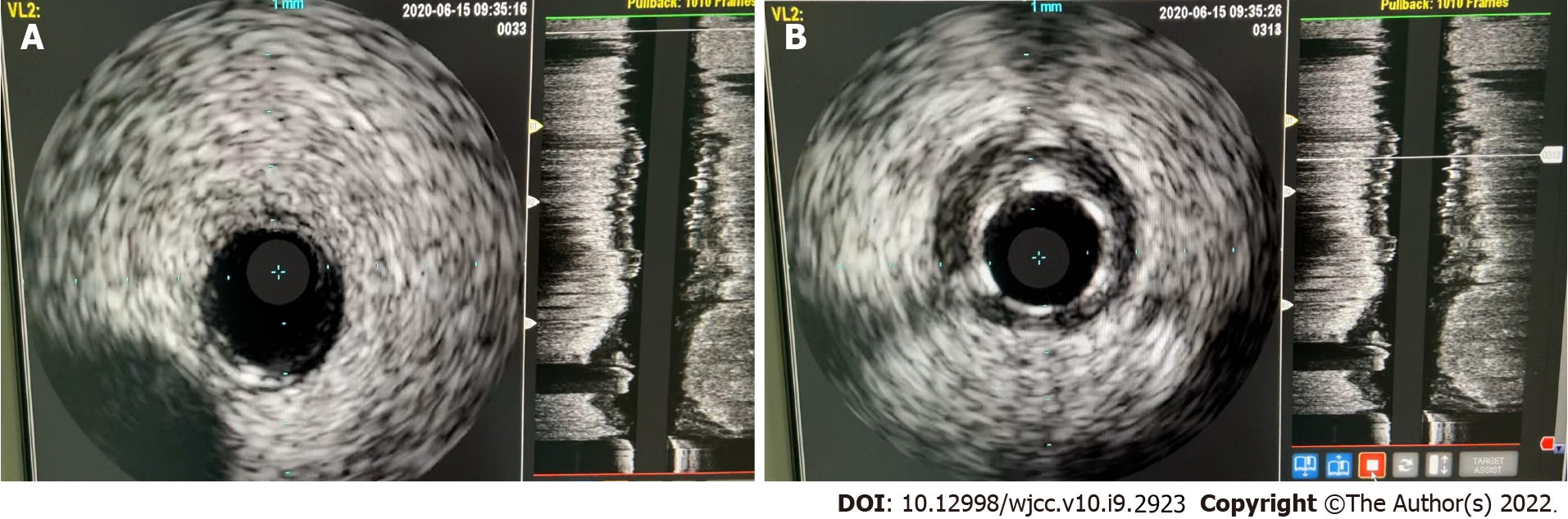

The patient was started on aspirin, clopidogrel, and atorvastatin. He recovered well from the operation and was scheduled to leave the hospital on June 15, 2020. However, on the day of the supposed discharge, he suddenly developed pain and discomfort in his back lasting over 10 min. The electrocardiogram showed a sinus rhythm with abnormal Q waves and ST elevations of 0.05-0.10 mv in leads II, III, and aVF (Figure 3). His symptoms improved slightly after sublingual nitroglycerin administration. AST was suspected, and he was transferred to the digital subtraction tomography room. Coronary angiography showed occlusion in the proximal stent (Figure 4A, Video 1). After performing percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty using a 2.5 mm × 20.0 mm balloon, the distal end of the RCA showed 90% stenosis. After expanding the stent sequentially from the distal to proximal segments using 15 atm pressure, RCA showed 90% stenosis (Figure 4B). The balloon was withdrawn, and intracoronary nitroglycerin was administered. Repeat angiography then revealed a patent distal right coronary artery with TIMI flow grade 3 (Figure 4C). An intravascular ultrasound catheter inserted in the distal end of the right coronary artery showed no obvious plaque (Figure 5A) and good adherence of the stent (Figure 5B). Postoperatively, the etiology of AST was suspected to be coronary artery spasms. Diltiazem administration was started to reduce coronary artery spasms. Postoperatively, back discomfort disappeared, and ST segments in leads II, III, and aVF dropped.

On hospitalization day 4, the patient reported no discomfort. He was discharged and started on antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel, diltiazem to reduce coronary spasms, and atorvastatin to stabilize atherosclerotic plaques. He reported no discomfort at the 2-mo follow-up.

AST is a serious complication of PCI. A recent meta-analysis of 30 clinical studies involving a total 221066 patients showed that the incidences of confirmed, highly probable, and possible AST were 0.4%, 0.2%, and 0.6%, respectively[6]. Despite the low incidence, AST leads to acute coronary syndrome and has a mortality rate of 20%-40%[7]. Understanding the risk factors for AST and pathophysiology of its occurrence and development may provide insights to aid the development of preventive and active treatments.

Iakovou et al[8] showed that decreased left ventricular ejection fraction is associated with the occurrence of AST. The ACUITY trial showed that insulin-treated diabetes and ST-segment elevations ≥ 0.1 mv are independent risk factors for AST within 1 year after PCI[9]. Kuchulakanti et al[7] showed that diabetes and acute and chronic renal failure are risk factors for AST in patients with drug-coated stent implants. A study on platelet hyperresponsiveness to adenosine diphosphate involving over 10000 patients proposed platelet hyperresponsiveness as a major risk factor for AST after PCI[10]. Insufficient use or premature discontinuation of antiplatelet drugs and clopidogrel resistance are also major causes of thrombosis after PCI. In recent years, cases of AST secondary to heparin-induced thrombocytopenia have been reported frequently[11,12].

Clinical risk factors for AST include current or past acute coronary syndrome, diabetes, and smoking. Coronary artery disease-related risk factors for AST include restenosis, bridging vessel disease, opening, coronary artery bifurcation, chronic occlusive arterial disease, and small vessel disease. Intraoperative technical risk factors for AST include the use of stents of inappropriate diameters, multiple overlapping stents, or excessively long stents; incomplete coverage of dissection; incomplete stent expansion; poor stent adherence; formation of thrombosis or intramural hematomas, and vascular damage secondary to mechanical manipulation. Drug-related risk factors for AST include poor response to aspirin or clopidogrel and premature discontinuation of antiplatelet drugs.

Coronary artery spasms can lead to acute coronary syndrome and myocardial infarction[13,14]; however, the occurrence of AST secondary to coronary spasms is rare and often only reported in the context of Kounis syndrome[15,16]. Kounis syndrome refers to the occurrence of acute coronary syndrome secondary to an allergic reaction. Exposure to allergens induces derangements in the neuroendocrine system and mast cell degranulation. This releases abundant inflammatory transmitters, which lead to coronary artery spasms or atherosclerotic plaque rupture. These events ultimately lead to stent thrombosis and AMI. Greif et al[5] reported a case of AST caused by a wasp bite after PCI. Tzanis et al[17] reported a case of early stent thrombosis secondary to an allergic reaction caused by rice intake. In our case, spasms were observed at the distal end of the coronary artery during PCI and resolved with nitroglycerin administration. At first, the spasms were not adequately appreciable and simply thought to be an effect of the surgical procedure, eluding the possibility of myocardial infarction resulting from a coronary artery spasm. During the second operation, the distal end of the stent showed severe stenosis after passing the balloon; however, the stenosis disappeared after intracoronary nitroglycerin administration, and subsequent intravascular ultrasound confirmed coronary artery spasms as the cause. The cold bath before the occurrence of AST was the patient’s first bath after 12 d of bed rest. It acted as an acute stimulus to the body and possibly caused neuroendocrine derangements that ultimately led to coronary artery spasms at the distal end of the stent. After adjusting the patient’s medications, subsequent follow-up consultations documented no cardiac events for 2 mo; this indicated the effectiveness of the medications used after PTCA and a good patient prognosis. However, for our patient, it is still difficult to ascertain the distal coronary spasm as the sole cause of AST.

Coronary artery spasms can cause both AMI and AST. For patients who exhibit coronary spasms during PCI, diltiazem administration is advised to reduce these spasms and prevent AST.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; externally peer-reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single-blind

Specialty type: Cardiac and cardiovascular systems

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: TERAGAWA H, Wang P S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Verhaegen C, Kautbally S, Zapareto DC, Brusa D, Courtoy G, Aydin S, Bouzin C, Oury C, Bertrand L, Jacques PJ, Beauloye C, Horman S, Kefer J. Early thrombogenicity of coronary stents: comparison of bioresorbable polymer sirolimus-eluting and bare metal stents in an aortic rat model. Am J Cardiovasc Dis. 2020;10:72-83. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Lupi A, Ugo F, De Martino L, Infantino V, Iannaccone M, Iorio S, Di Leo A, Colangelo S, Zanera M, Schaffer A, Persampieri S, Garbo R, Senatore G. Real-World Experience With a Tapered Biodegradable Polymer-Coated Sirolimus-Eluting Stent in Patients With Long Coronary Artery Stenoses. Cardiol Res. 2020;11:219-225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Natsuaki M, Morimoto T, Watanabe H, Abe M, Kawai K, Nakao K, Ando K, Tanabe K, Ikari Y, Igarashi Hanaoka K, Morino Y, Kozuma K, Kadota K, Kimura T; STOPDAPT-1 and STOPDAPT-2 Trial Investigators. Clopidogrel Monotherapy vs. Aspirin Monotherapy Following Short-Term Dual Antiplatelet Therapy in Patients Receiving Everolimus-Eluting Coronary Stent Implantation. Circ J. 2020;84:1483-1492. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Byrne RA, Joner M, Kastrati A. Stent thrombosis and restenosis: what have we learned and where are we going? Eur Heart J. 2015;36:3320-3331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 337] [Cited by in RCA: 422] [Article Influence: 42.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Greif M, Pohl T, Oversohl N, Reithmann C, Steinbeck G, Becker A. Acute stent thrombosis in a sirolimus eluting stent after wasp sting causing acute myocardial infarction: a case report. Cases J. 2009;2:7800. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lipinski MJ, Escarcega RO, Baker NC, Benn HA, Gaglia MA Jr, Torguson R, Waksman R. Scaffold Thrombosis After Percutaneous Coronary Intervention With ABSORB Bioresorbable Vascular Scaffold: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;9:12-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 15.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kuchulakanti PK, Chu WW, Torguson R, Ohlmann P, Rha SW, Clavijo LC, Kim SW, Bui A, Gevorkian N, Xue Z, Smith K, Fournadjieva J, Suddath WO, Satler LF, Pichard AD, Kent KM, Waksman R. Correlates and long-term outcomes of angiographically proven stent thrombosis with sirolimus- and paclitaxel-eluting stents. Circulation. 2006;113:1108-1113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 495] [Cited by in RCA: 471] [Article Influence: 24.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Iakovou I, Schmidt T, Bonizzoni E, Ge L, Sangiorgi GM, Stankovic G, Airoldi F, Chieffo A, Montorfano M, Carlino M, Michev I, Corvaja N, Briguori C, Gerckens U, Grube E, Colombo A. Incidence, predictors, and outcome of thrombosis after successful implantation of drug-eluting stents. JAMA. 2005;293:2126-2130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2402] [Cited by in RCA: 2331] [Article Influence: 116.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Généreux P, Madhavan MV, Mintz GS, Maehara A, Palmerini T, Lasalle L, Xu K, McAndrew T, Kirtane A, Lansky AJ, Brener SJ, Mehran R, Stone GW. Ischemic outcomes after coronary intervention of calcified vessels in acute coronary syndromes. Pooled analysis from the HORIZONS-AMI (Harmonizing Outcomes With Revascularization and Stents in Acute Myocardial Infarction) and ACUITY (Acute Catheterization and Urgent Intervention Triage Strategy) TRIALS. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:1845-1854. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 223] [Cited by in RCA: 331] [Article Influence: 30.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Stone GW, Witzenbichler B, Weisz G, Rinaldi MJ, Neumann FJ, Metzger DC, Henry TD, Cox DA, Duffy PL, Mazzaferri E, Gurbel PA, Xu K, Parise H, Kirtane AJ, Brodie BR, Mehran R, Stuckey TD; ADAPT-DES Investigators. Platelet reactivity and clinical outcomes after coronary artery implantation of drug-eluting stents (ADAPT-DES): a prospective multicentre registry study. Lancet. 2013;382:614-623. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 642] [Cited by in RCA: 677] [Article Influence: 56.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Voudris V, Georgiadou P, Kalogris P, Kostelidou T, Karabinis A, Gerotziafas G. Missed Heparin-Induced Thrombocytopenia (HIT) Diagnosis in a Patient with Acute Stent Thrombosis. Am J Case Rep. 2019;20:753-757. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ben Messaoud M, Maatouk M, Boussaada MM, Mahjoub M, Mnari W, Gamra H. Case Report: Concomitant coronary stent and femoral artery thrombosis in the setting of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. F1000Res. 2019;8:667. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Om SY, Yoo SY, Cho GY, Kim M, Woo Y, Lee S, Kim DH, Song JM, Kang DH, Cheong SS, Park SW, Park SJ, Song JK. Diagnostic and Prognostic Value of Ergonovine Echocardiography for Noninvasive Diagnosis of Coronary Vasospasm. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;13:1875-1887. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Niccoli G, Camici PG. Myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary arteries: what is the prognosis? Eur Heart J Suppl. 2020;22:E40-E45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Sciatti E, Vizzardi E, Cani DS, Castiello A, Bonadei I, Savoldi D, Metra M, D'Aloia A. Kounis syndrome, a disease to know: Case report and review of the literature. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis. 2018;88:898. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Chen JP, Hou D, Pendyala L, Goudevenos JA, Kounis NG. Drug-eluting stent thrombosis: the Kounis hypersensitivity-associated acute coronary syndrome revisited. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;2:583-593. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Tzanis G, Bonou M, Mikos N, Biliou S, Koniari I, Kounis NG, Barbetseas J. Early stent thrombosis secondary to food allergic reaction: Kounis syndrome following rice pudding ingestion. World J Cardiol. 2017;9:283-288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |