Published online Mar 26, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i9.2858

Peer-review started: September 9, 2021

First decision: December 9, 2021

Revised: December 16, 2021

Accepted: January 22, 2022

Article in press: January 22, 2022

Published online: March 26, 2022

Processing time: 194 Days and 0.6 Hours

Delusional parasitosis is characterized by a false belief of being infested with parasites, insects, or worms. This illness is observed in patients with Parkinson’s disease and is usually related to dopaminergic treatment. To our knowledge, no cases of delusional parasitosis have been reported as a premotor symptom or non-motor symptom of Parkinson’s disease.

A 75-year-old woman presented with a complaint of itching that she ascribed to the presence of insects in her skin, and she had erythematous plaques on her trunk, arms, buttocks, and face. These symptoms started two months before the visit to the hospital. She took medication, including antipsychotics, with a diagnosis of delusional parasitosis, and the delusion improved after three months. A year later, antipsychotics were discontinued, and anxiety and depression were controlled with medication. However, she complained of bradykinesia, masked face, hand tremor, and mild rigidity, and we performed fluorinated N-3-fluoropropyl-2β-carbomethoxy-3β-(4-iodophenyl) nortropane positron emission tomography (PET), which showed mildly decreased DAT binding in the right anterior putamen and caudate nucleus. Parkinson’s disease was diagnosed on the basis of PET and clinical symptoms.

In conclusion, delusional parasitosis can be considered a non-motor sign of Parkinson’s disease along with depression, anxiety, and constipation.

Core Tip: Cases of delusional parasitosis during medication, such as dopamine agonists, in Parkinson’s disease have been reported. However, this case report shows that delusional parasitosis occurred before the diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease. In addition, unlike in other treatments for delusional disorders, the patient’s delusions improved quickly. After delusional parasitosis improved, the motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease were observed, and Parkinson’s disease was diagnosed. The sudden onset of delusional parasitosis in elderly without a psychiatric history could be associated with the premotor or non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease. Therefore, an evaluation of Parkinson’s disease should be considered for elderly with delusional parasitosis.

- Citation: Oh M, Kim JW, Lee SM. Delusional parasitosis as premotor symptom of parkinson’s disease: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(9): 2858-2863

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i9/2858.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i9.2858

Delusional parasitosis is characterized by a false belief that one is infested by parasites, insects, worms, bacteria, or other living organisms despite the absence of medical evidence[1]. Patients with delusional parasitosis report tactile hallucinations or paresthesia and often have skin damage from their attempts to remove the parasites. This illness can be classified into primary and secondary forms: the former cannot be explained by other psychiatric or organic diseases, whereas the latter can occur in other psychiatric disorders and medical illnesses, as well as in substance abuse disorders and medication side effects[2]. The treatment of delusional parasitosis is a therapeutic challenge because many patients refuse psychiatric treatment owing to the belief that parasitic infestation is unshakable and not a psychiatric condition.

Patients with Parkinson’s disease present with motor and non-motor symptoms, including cognitive decline, insomnia, depressive mood, anxiety, hallucinations, and delusions[3]. Psychotic symptoms are usually related to dopaminergic treatment, and secondary delusional parasitosis can be observed but very rarely. Few cases of delusional parasitosis associated with antiparkinsonian treatment have been reported, and the time of onset in these cases was different (less than 1 wk to 12 mo after medication). This suggests that the onset of delusional parasitosis is not related to the duration of treatment[4]. To date, no case of delusional parasitosis has been reported as a premotor symptom or non-motor symptom in Parkinson’s disease.

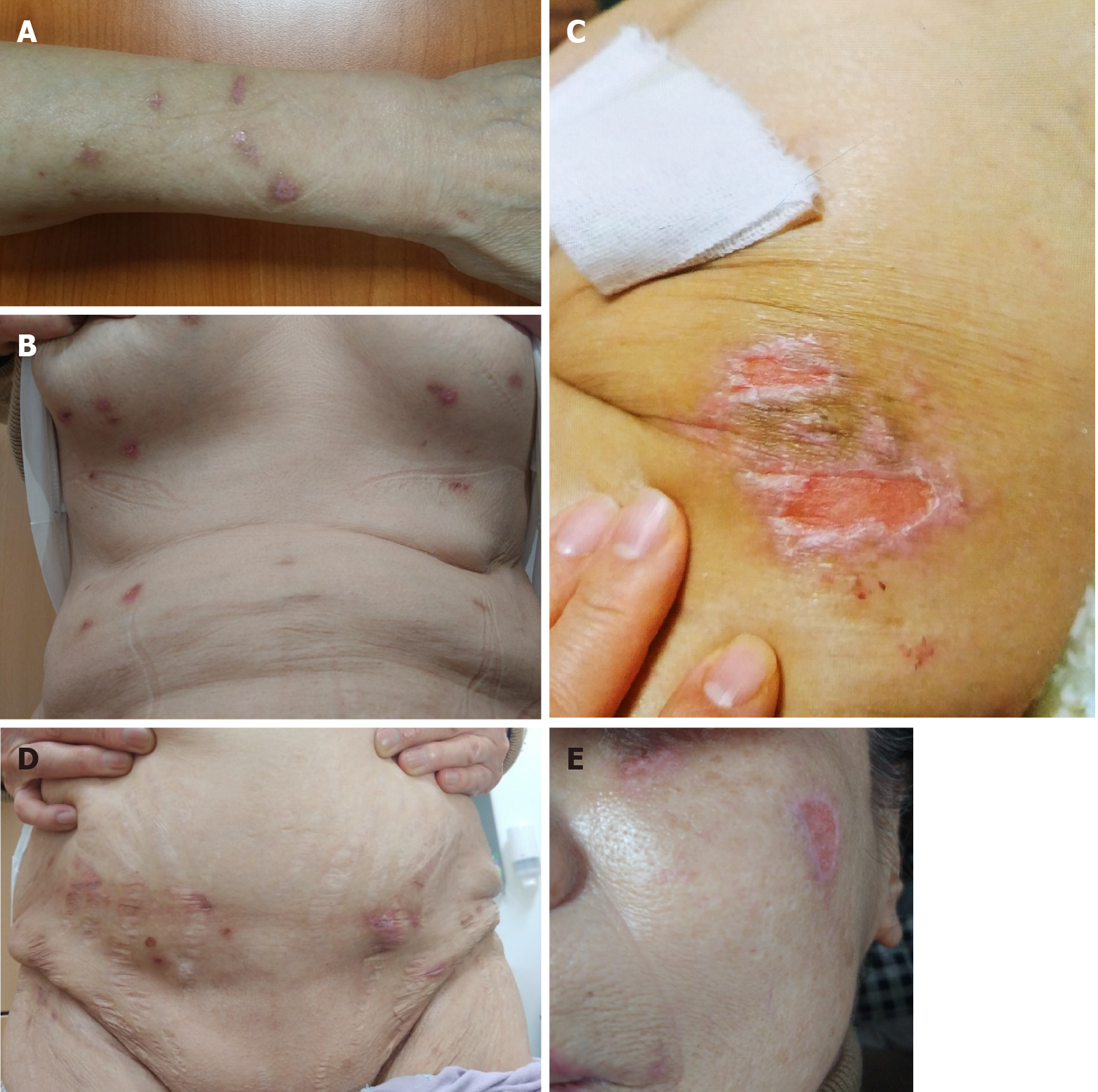

A 75-year-old woman was referred from the dermatology department to the psychiatric department with a complaint of itching due to the presence of insects in the skin. She also presented with erythematous plaques on the trunk, arms, buttocks, and face.

Four months prior, the patient underwent arthroscopic rotator cuff repair of the right shoulder. Two months after surgery, she started scratching her body and picking her skin with toothpicks and cotton swabs to catch insects and worms. She also collected insects and worms in a container to show them to her family, but there were no insects in the container. She kept scratching and picking; therefore, her skin was slow to improve even though the dermatologist already treated the skin lesion. She started taking medication (olanzapine 5 mg, etizolam 0.25 mg, and escitalopram 10 mg) three weeks before the onset of delusional parasitosis because of anxiety and insomnia. Anxiety and insomnia improved with medication; however, the delusional parasitosis continued.

The patient’s husband died one year ago. She had a mild depressive mood but had never been treated. She had no history of neurological diseases.

There was no family history of psychiatric diseases.

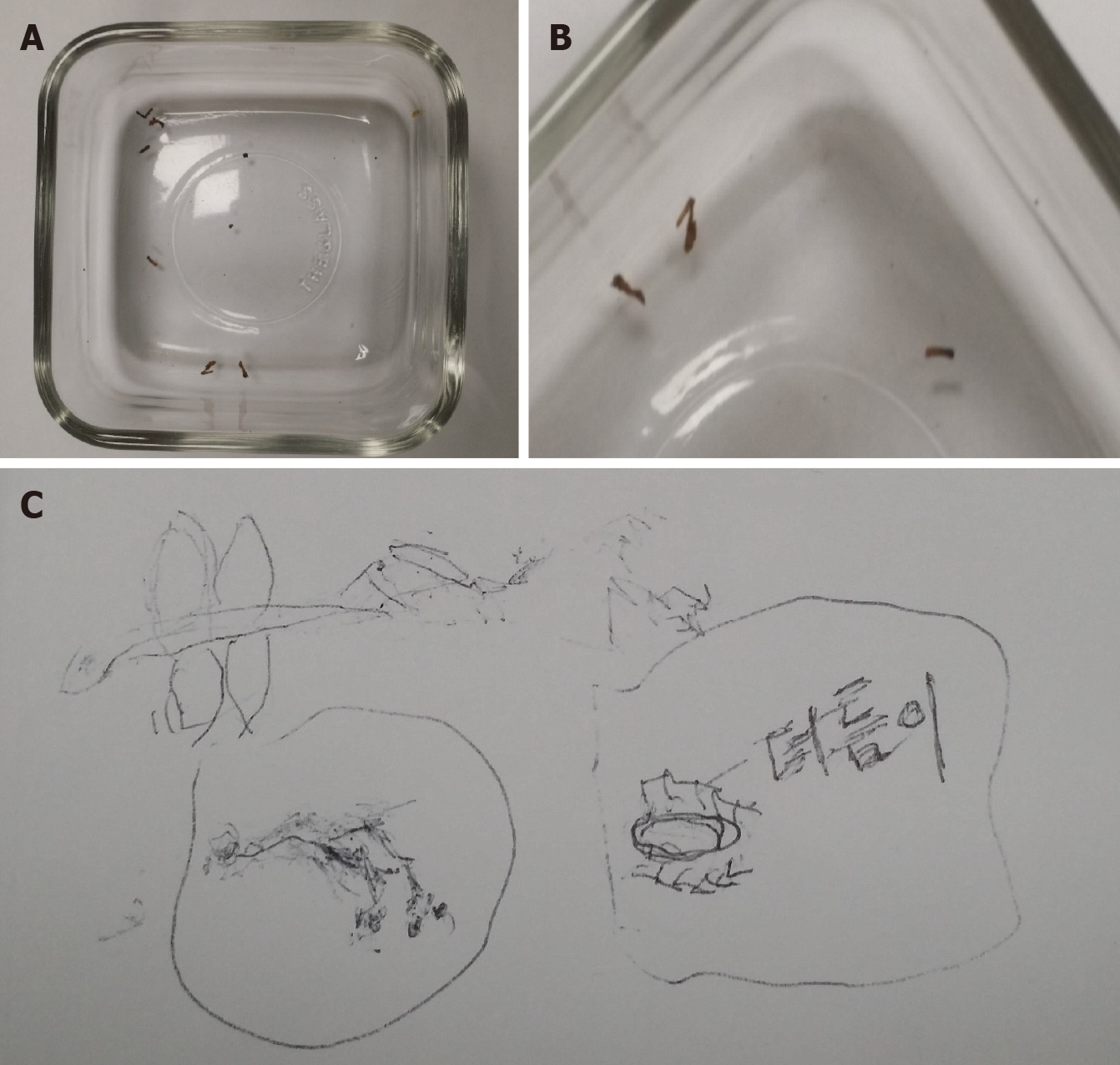

The patient was anxious and agitated, and she explained the insects in her skin in detail. She also reacted sensitively, and her family did not believe her. She presented a container with various dust particles and pieces of skin and stated that it contained insects that came from her skin (Figure 1). Her cognitive function was generally intact [Korean version of the Mini-Mental Status Examination of the CERAD assessment packet (MMSE-KC 29/30)]. She had erythematous plaques on the trunk, arms, buttocks, and face (Figure 2).

Skin biopsy revealed contact dermatitis and dermatofibroma.

A mild degree of global cerebral atrophy and small vessel disease was observed at both the periventricular white matter and deep white matter via magnetic resonance imaging of the brain.

The final diagnosis was delusional parasitosis and parkinson’s disease.

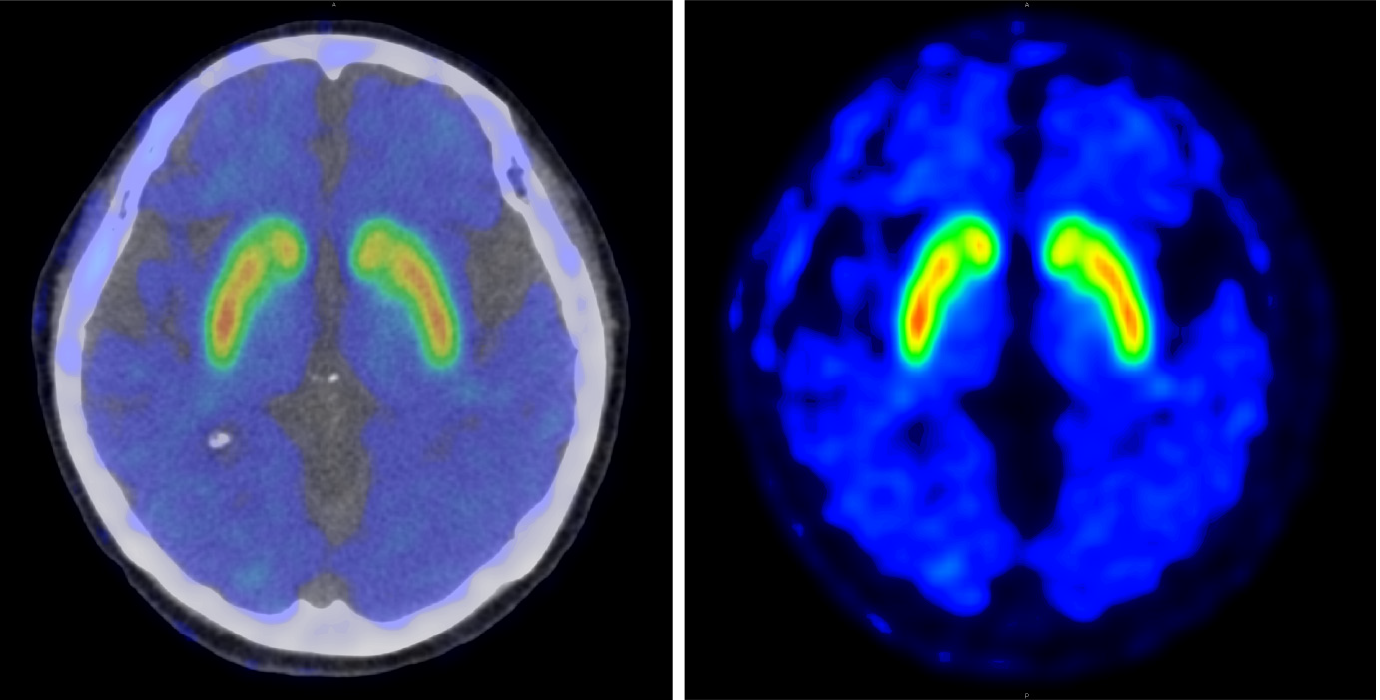

The delusions improved after three months of treatment with olanzapine 5 mg, aripiprazole 2 mg, escitalopram 10 mg, and alprazolam 0.125 mg. Thereafter, treatment was mainly focused on anxiety and depression. A year later, all antipsychotics were stopped, but she complained of bradykinesia, masked face, hand tremor, and mild rigidity. Considering the patient’s symptoms, we performed fluorinated N-3-fluoropropyl-2β-carbomethoxy-3β-(4-iodophenyl) nortropane positron emission tomography (PET), and the results showed mildly decreased DAT binding in the right anterior putamen and caudate nucleus (Figure 3).

To our knowledge, this is the first case of delusional parasitosis as a prodromal symptom of Parkinson’s disease. To date, there have been few reports of delusional parasitosis linked to the treatment complications of Parkinson’s disease using dopamine agonists. However, no cases of delusional parasitosis have been reported before the onset of motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease and without dopamine administration.

The etiology and pathophysiology of delusional parasitosis are unknown. One possible etiologic hypothesis is related to decreased striatal dopamine transporter functioning, which leads to increased extracellular dopamine level[5]. In addition, the striato-thalamo-cortical loop and putamen dysfunction may play an important role in somatic delusions, tactile misperceptions, and visual hallucinations[6]. The putamen contains bimodal cells that process information on somatosensory stimuli such as light touch, joint movement, and muscle pressure[7], and the dysfunction of these cells may be responsible for infestation. The role of the striatum and the efficacy of antipsychotics represent dopamine dysfunction in delusional parasitosis, and it is more strongly supported by delusional parasitosis in intoxication with substances that affect dopamine transporters (e.g., cocaine and methylphenidate).

Parkinson’s disease is the second most common progressive neurodegenerative disorder and occurs mostly in older persons. The degeneration or loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra and the development of Lewy bodies in dopaminergic neurons is the pathological definition of Parkinson’s disease[8]. At the time that Parkinson’s disease is diagnosed with motor symptoms, dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra had already decreased by 58%-84%, and striatal dopamine content had already decreased by 60%-80%[9]. The loss of dopaminergic neurons leads to the marked impairment of motor control. In addition to motor symptom such as rigidity, tremor, and bradykinesia, non-motor symptoms including cognitive dysfunction, autonomic nervous system failure, sleep disturbance, and mood disorder can be represented in Parkinson’s disease. Several non-motor symptoms can precede the development of motor symptoms by years to decades, and the diagnosis of parkinson’s disease is often delayed, thus resulting in inappropriate care and treatment. It is also known that 90% of patients experience non-motor symptoms during the course of the disease[10]. Most of the early features of parkinson’s disease are non-motor symptoms, and premotor symptoms that have been strongly linked to Parkinson’s disease include loss of smell, constipation, REM sleep behavior disorder, and depression. By contrast, fatigue, anxiety, cognition, personality change, and apathy are premotor symptoms that have been less strongly linked to Parkinson’s disease[11]. To date, hallucinations, psychosis, and delusional parasitosis have never been reported as premotor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease.

According to the aberrant salience hypothesis, psychotic symptoms may arise from the aberrant assignment of salience to irrelevant environmental stimuli imbuing them with meaningfulness and relevance[12]. In conditions of dopamine dysregulation, such as Parkinson’s disease or delusional disorder and schizophrenia, aberrant salience is assigned to normal stimuli, which then leads to delusion formation driven by the dysfunction of dopamine neurons. Normal events such as flakes of dry skin and rashes are probably attributed to aberrant salience, which leads to delusional beliefs in delusional parasitosis patients[13]. Delusional parasitosis and Parkinson’s disease may share the same key neurotransmitters and may involve the same anatomic structures. Future studies are required to improve our understanding of the neural networks involved in the pathophysiology of delusional parasitosis.

In conclusion, delusional parasitosis could be a premotor symptom or a non-motor symptom in Parkinson’s disease, along with constipation, loss of smell, and depression. We recommend an evaluation of Parkinson’s disease for elderly patients with sudden onset of delusional parasitosis without a psychiatric history.

We would like to thank the patient for their understanding and willingness to participate in this study.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Psychiatry

Country/Territory of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Feng J S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Trabert W. 100 years of delusional parasitosis. Meta-analysis of 1,223 case reports. Psychopathology. 1995;28:238-246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Prakash J, Shashikumar, R., Bhat, P. S., Srivastava, K., Nath, S., Rajendran A. Delusional parasitosis: Worms of the mind. Ind Psychiatry J. 2012;21: 72-74. |

| 3. | Truong DD, Bhidayasiri R, Wolters E. Management of non-motor symptoms in advanced Parkinson disease. J Neurol Sci. 2008;266:216-228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Aarsland D, Larsen JP, Cummings JL, Laake K. Prevalence and Clinical Correlates of Psychotic Symptoms in Parkinson Disease. Arch Neurol. 1999;56:595. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 255] [Cited by in RCA: 245] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Wolf RC, Huber M, Depping MS, Thomann PA, Karner M, Lepping P, Freudenmann RW. Abnormal gray and white matter volume in delusional infestation. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2013;46:19-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Huber M, Karner M, Kirchler E, Lepping P, Freudenmann RW. Striatal lesions in delusional parasitosis revealed by magnetic resonance imaging. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2008;32:1967-1971. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Làdavas E, Zeloni G, Farnè A. Visual peripersonal space centred on the face in humans. Brain. 1998;121:2317-2326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Macphee GJA, Stewart DA. Parkinson’s disease - Pathology, aetiology and diagnosis. Rev Clin Gerontol 2012;22:165–78. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 9. | Tolosa E, Compta Y, Gaig C. The premotor phase of Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2007;13 Suppl:S2-S7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Löhle M, Storch A, Reichmann H. Beyond tremor and rigidity: non-motor features of Parkinson’s disease. J Neural Transm. 2009;116: 1483-1492. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Siderowf A, Lang AE. Premotor Parkinson's disease: concepts and definitions. Mov Disord. 2012;27:608-616. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Pankow A, Katthagen T, Diner S, Deserno L, Boehme R, Kathmann N, Gleich T, Gaebler M, Walter H, Heinz A, Schlagenhauf F. Aberrant Salience Is Related to Dysfunctional Self-Referential Processing in Psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 2016;42:67-76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Flann S, Shotbolt J, Kessel B, Vekaria D, Taylor R, Bewley A, Pembroke A. Three cases of delusional parasitosis caused by dopamine agonists. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;35:740-742. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |