Published online Mar 26, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i9.2829

Peer-review started: August 10, 2021

First decision: December 1, 2021

Revised: December 6, 2021

Accepted: February 19, 2022

Article in press: February 19, 2022

Published online: March 26, 2022

Processing time: 224 Days and 3.5 Hours

Sarcomatoid intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (SICC) is an extremely rare and highly invasive malignant tumor of the liver. The precise pathologic mechanism of SICC has not been clearly identified, and the prognosis is very poor. The effectiveness of the treatment strategy of radical hepatectomy combined with Huaier granules has not yet been reported.

The patient was a 69-year-old male who presented with intermittent right upper abdominal pain for one month and 4-pound weight loss before admission. Abdominal magnetic resonance imaging and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography showed multiple stones in the bile ducts accompanied by dilatation of the intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts. The preoperative diagnoses were right intrahepatic bile duct stones and extrahepatic bile duct stones; thus, surgical resection was performed. Choledochoscopy showed that the bile duct wall of the right anterior lobe was thickened, and a mass was visible in the duct. Then, a biopsy was performed, and rapid frozen-section biopsy analysis indicated that the tumor was malignant. The final diagnosis was SICC (T1aN0M0). Huaier granules were taken by the patient as anticancer therapy after surgery. The patient attended follow-up for 72 mo with no tumor recurrence or metastasis.

Sarcomatous intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma is an extremely rare, aggressive malignancy, and the diagnostic gold standard is pathological diagnosis. We reported the first case of successful treatment with Huaier granules as anticancer therapy after surgery, which indicated that Huaier granules are safe and effective. Further studies are needed to study the anticancer molecular mechanisms of Huaier granules in sarcomatous intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma.

Core Tip: Sarcomatoid intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (SICC) is an extremely rare and highly invasive malignant tumor of the liver. The precise pathologic mechanism of SICC has not been clearly identified, and the prognosis is very poor. The effectiveness of the treatment strategy of radical hepatectomy combined with Huaier granules has not yet been reported. A 69-year-old male with long-term use of Huaier granules for anticancer therapy postoperation achieved long-term survival with no tumor recurrence or metastasis. We reported the first case of successful treatment with Huaier granules as an adjuvant treatment after surgery and demonstrated that Huaier granules are safe and effective.

- Citation: Feng JY, Li XP, Wu ZY, Ying LP, Xin C, Dai ZZ, Shen Y, Wu YF. Sarcomatoid intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma with good patient prognosis after treatment with Huaier granules following hepatectomy: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(9): 2829-2835

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i9/2829.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i9.2829

Sarcomatoid intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (SICC) is rare and has only been reported sporadically worldwide, mainly in individual case reports[1]. The precise pathologic mechanism of SICC has not been clearly identified, and the prognosis is poor, with a median survival period of only 6-11 mo[2]. Surgical resection is recommended as the main treatment option[3]; however, patients still have a relatively poor prognosis due to the challenging diagnosis and frequent metastasis to other organs or invasion of adjacent vasculature[4]. Here, we present the first case of a patient with SICC successfully treated with Huaier granules as an adjuvant treatment after surgery.

Intermittent right upper abdominal pain for one month and 4-pound weight loss.

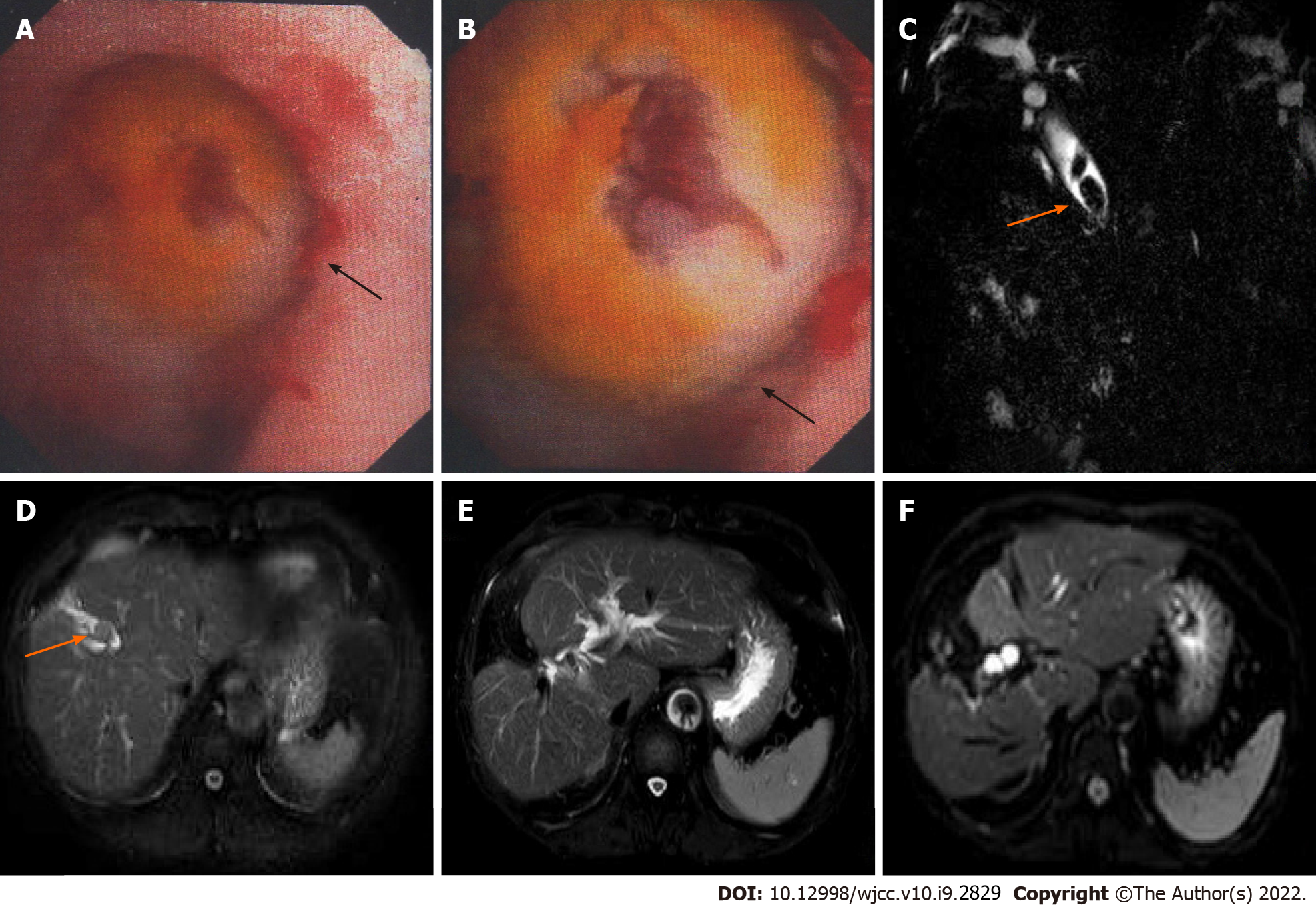

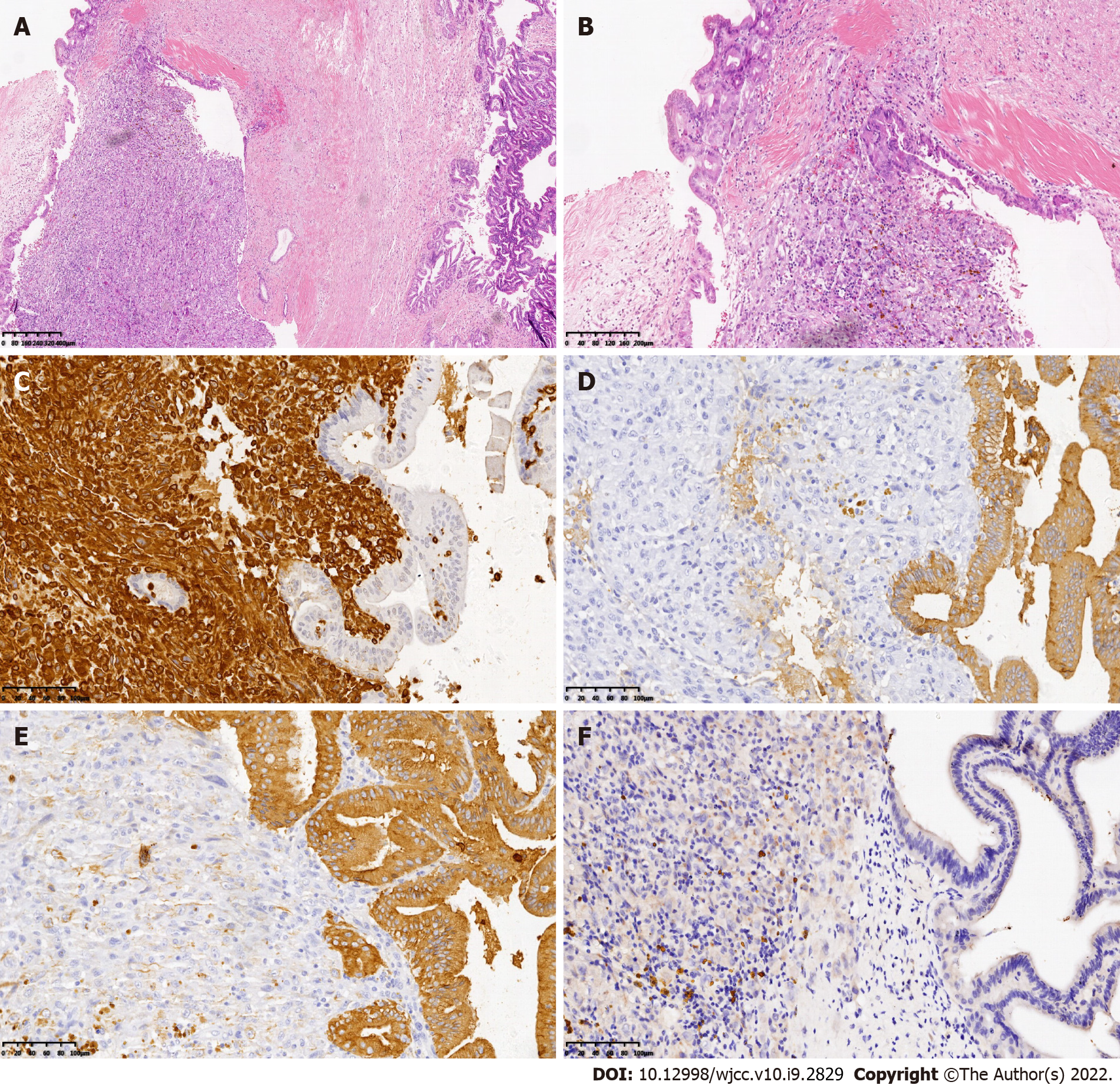

The patient was a 69-year-old Chinese man admitted to the hospital in December 2014 due to intermittent right upper abdominal pain for one month and 4-pound weight loss. The preoperative diagnoses were right intrahepatic bile duct stones, extrahepatic bile duct stones and postcholecystectomy status; thus, surgical resection was performed. During the operation, no space-occupying lesions of the liver or related swollen lymph nodes were found. Choledochoscopy showed that the bile duct wall of the right anterior lobe was thickened, and a mass was visible in the duct (Figure 1A and B). In addition, a biopsy was performed, and rapid frozen-section biopsy analysis indicated that the tumor was malignant. Thus, we diagnosed the patient with a malignant liver tumor and performed right hepatectomy combined with regional lymphadenectomy. The operative time was four and a half hours, the intraoperative blood loss during the operation was 300 mL, and the duration of hospital stay after surgery was 16 d. Histopathological examination of the liver tissue (Figure 2) showed the existence of an SICC (1.5 cm × 1.5 cm). No evidence of cancer infiltration was found at the margin of the hepatectomy, in the nerves, or in the vessels. The tumor stage was T1aN0M0 based on the 7th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer TNM staging system.

Cholecystectomy had been performed at another hospital 5 years prior for gallbladder stones with cholecystitis.

Physical examination showed a soft abdomen and tenderness in the right upper abdomen, no rebound pain, and no abdominal mass or swollen lymph nodes.

The data obtained by serological examination were as follows: A white blood cell count of 8.2 × 109/L [normal range: (4-10) × 109/L], with 69.8% neutrophils; a hemoglobin level of 129 g/L (normal range: 130-175 g/L); a platelet count of 303 × 109/L [normal range: (125-350) × 109/L]; an albumin level of 39.3 g/L (normal range: 40-55.0 g/L); a globulin level of 21.2 g/L (normal range: 20-40 g/L); an alanine aminotransferase concentration of 135 U/L (normal range: 9-50 U/L); an aspartate aminotransferase concentration of 85 U/L (normal range: 15-40 U/L); a total bilirubin level of 69.7 μmol/L (normal range: 3.4-17.1 μmol/L); a direct bilirubin level of 30.4 μmol/L (normal range: 1.7-6.8 μmol/L); an HBsAg level of 0.352 COI (< 1.000); an HBsAb level of 5.23 IU/L (2-10iu/L); an HBeAg level of 0.095 COI (< 1.000); hepatitis C antibody IgG was negative; an α-fetoprotein concentration of 1.83 ng/mL (normal range: < 9 ng/mL); a carcinoembryonic antigen level of 1.88 ng/mL (normal range: < 5 ng/mL); and a serum carbohydrate antigen (CA) level of 19-9 of 89.6 U/mL (normal range: < 35 U/mL). Immunohistochemical staining showed that atypical cells in the tumor were positive for pan-cytokeratin (pan-CK) and vimentin but negative for hepatocyte paraffin 1 (HepPar-1).

Abdominal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) showed multiple stones in the bile ducts accompanied by dilatation of the intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts (Figure 1C and D). Abdominal ultrasound showed moderate echogenicity in the right lobe of the liver, suggesting inflammatory changes.

Sarcomatoid intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, SICC (T1aN0M0); right intrahepatic bile duct stones; extrahepatic bile duct stones; and postcholecystectomy status.

Surgery: Right hepatectomy combined with regional lymphadenectomy. After surgery, the patient had been taking Huaier granules (20 g tid po) as anticancer therapy until now.

Routine follow-up was sustained in the surgical clinic, and no other emerging lesions were discovered in the liver. The patient has now attended follow-up for 72 mo, and no tumor recurrence or metastasis has been observed (Figure 1E and F).

SICC is an extremely rare histological subtype of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC), accounting for 4.5% of ICCs[1] and less than 1% of hepatobiliary system malignancies[4]. Fewer than 45 cases have been reported in the English literature[2]. SICC is defined by the World Health Organization as cholangiocarcinoma with spindle cell areas resembling spindle cell sarcoma or fibrosarcoma or with features of malignant fibrous histiocytoma[5]. Researchers have hypothesized that anticancer therapy, such as transcatheter arterial chemoembolization and radiation therapy, might cause the evolution of sarcomatoid changes or promote the transformation of epithelial cells into sarcoma cells in sarcomatous hepatocellular carcinoma[3]. In contrast, there are no reports regarding the relationship between SICC and anticancer therapy[6]. In addition, sarcomatoid changes in cholangiocellular carcinoma are believed to be due to the natural progression of the disease[3,7], but the precise pathological mechanism that leads to SICC has not been fully elucidated. In our case, the inflammatory irritation caused by bile duct stones may be the main reason. SICC has no specific clinical features and can often be asymptomatic until it becomes large or combined with intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile duct stones[8]. SICC produces nonspecific symptoms or signs, such as abdominal pain, fever, abdominal mass, nausea, vomiting, fatigue, weight loss, and, rarely, acute intra-abdominal bleeding secondary to tumor rupture. Abdominal pain and fever are the most common symptoms[8]. In our study, the patient presented with abdominal pain as the primary symptom, consistent with previous reports in the literature, which may be related to biliary infection caused by intrahepatic and extrahepatic biliary stones.

Radiological imaging of SICC has been described to show an enlarged, low-density lesion, with a clear or unclear mass, sometimes with intratumor hemorrhage[9], which are common characteristics similar to ordinary ICC. In addition, serological tumor markers, such as CA19-9, carcinoembryonic antigen, and alpha-fetoprotein levels, were negative or low in SICC according to previous studies[4,8] and may also not be sufficient to diagnose SICC. Therefore, the definitive diagnosis of SICC can only be determined by biopsy and is dependent on histopathological and immunohistochemical examinations.

The histopathological features of SICC indicate the coexistence of adenocarcinoma cells with differentiated sarcomatoid cells, which are spindle-shaped, round-shaped or oval-shaped and arranged in bundles or weaves. Immunohistochemical staining of the tumors is positive for both epithelial cholangiogenic tumor markers (pan-CK, CK19, CK8) and the mesenchymal tumor marker vimentin and negative for HepPar-1, which is used to distinguish HCC from cholangiocarcinoma and metastatic carcinoma[6,10]. In our case, pan-CK, CK19 and vimentin were positive, and HepPar-1 was negative, which was similar to the results described in previous reports.

The degree of SICC malignancy is significantly higher than that of traditional cholangiocarcinoma. To date, no definitive comprehensive treatment for SICC is available, but radical liver resection is generally recommended as the first treatment option, and patients with SICC who undergo surgical resection have a significantly higher survival rate than those who do not[3,10]. Therefore, complete resection of the tumor, such as regular hepatic lobectomy, hemihepatectomy and trisegmentectomy, may result in a satisfactory treatment outcome. Malhotra et al[7] reported that postoperative treatment with a combination of gemcitabine and cisplatin could improve the prognosis and prolong the survival time of patients with SICC to 29 mo after hepatectomy. Gu et al[11] also reported that doxorubicin, Taxol, cisplatin, and cyclophosphamide as adjuvant chemotherapy after hepatectomy might prolong the survival time of patients with sarcomatoid carcinomas. In contrast, Aghajanian et al[12] described that uterine carcinosarcoma was not sufficiently sensitive to the combination of paclitaxel and carboplatin. The efficacy of postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy for SICC has not been confirmed.

Huaier granule, the aqueous product of Huaier extract, is a traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) approved by the Chinese State Food and Drug Administration (SFDA). Huaier granules are different from cytotoxic drugs, target agents, or immune checkpoint inhibitors and can be used alone or in combination with chemotherapy or radiation therapy, leading to increased therapeutic effects, prolonged recurrence-free survival and reduced recurrence rates in malignant lymphoma, osteosarcoma, liver cancer, breast cancer, rectal cancer, lung cancer, pancreatic adenocarcinoma, gastric cancer and colon cancer[13,14]. Currently, no therapeutic effect of Huaier granules for SICC has been reported. In the case presented here, the patient took Huaier granules as postoperative adjuvant treatment without interruption. Postoperative contrast-enhanced computed tomography and contrast-enhanced MRI showed no tumor recurrence. Routine follow-up was sustained in the surgical clinic, and no other emerging lesions were observed in the liver. The patient has now attended follow-up for 72 mo, and no tumor recurrence or metastasis has been observed. Qi et al[15] reported that Huaier granules could inhibit the expression of N-cadherin and vimentin to prevent the metastasis of tumor cells. Additionally, Huaier granules could block the STAT3 signaling pathway by inhibiting STAT3 activation. This may be the main mechanism underlying the effectiveness of Huaier granules. Nevertheless, this was the first study to use Huaier granules as a postoperative adjuvant treatment for SICC; the efficacy of Huaier granules remains unclear and needs to be further studied.

SICC is an extremely rare, aggressive malignancy, and the diagnostic gold standard is pathological diagnosis. We reported the first case of successful treatment with Huaier granules as anticancer therapy after surgery, which indicated that Huaier granules are safe and effective. Further research is needed to study the anticancer molecular mechanisms of Huaier granules in sarcomatous intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Gencdal G, Gupta R, Ozdemir F, Shrestha A S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: A P-Editor: Fan JR

| 1. | Inoue Y, Lefor AT, Yasuda Y. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma with sarcomatous changes. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2012;6:1-4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Wang Y, Ming JL, Ren XY, Qiu L, Zhou LJ, Yang SD, Fang XM. Sarcomatoid intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma mimicking liver abscess: A case report. World J Clin Cases. 2020;8:208-216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Okabayashi T, Shima Y, Iwata J, Iiyama T, Sumiyoshi T, Kozuki A, Tokumaru T, Hata Y, Noda Y, Morita M. Surgical outcomes for 131 cases of carcinosarcoma of the hepatobiliary tract. J Gastroenterol. 2014;49:982-991. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kim DK, Kim BR, Jeong JS, Baek YH. Analysis of intrahepatic sarcomatoid cholangiocarcinoma: Experience from 11 cases within 17 years. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25:608-621. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Nagtegaal ID, Odze RD, Klimstra D, Paradis V, Rugge M, Schirmacher P, Washington KM, Carneiro F, Cree IA; WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. The 2019 WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system. Histopathology. 2020;76:182-188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2554] [Cited by in RCA: 2441] [Article Influence: 488.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 6. | Sato K, Murai H, Ueda Y, Katsuda S. Intrahepatic sarcomatoid cholangiocarcinoma of round cell variant: a case report and immunohistochemical studies. Virchows Arch. 2006;449:585-590. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Malhotra S, Wood J, Mansy T, Singh R, Zaitoun A, Madhusudan S. Intrahepatic sarcomatoid cholangiocarcinoma. J Oncol. 2010;2010:701476. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Wang T, Kong J, Yang X, Shen S, Zhang M, Wang W. Clinical features of sarcomatoid change in patients with intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma and prognosis after surgical liver resection: A Propensity Score Matching analysis. J Surg Oncol. 2020;121:524-537. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Bridgewater J, Galle PR, Khan SA, Llovet JM, Park JW, Patel T, Pawlik TM, Gores GJ. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J Hepatol. 2014;60:1268-1289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 862] [Cited by in RCA: 1076] [Article Influence: 97.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Zhang N, Li Y, Zhao M, Chang X, Tian F, Qu Q, He X. Sarcomatous intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: Case report and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e12549. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Gu KW, Kim YK, Min JH, Ha SY, Jeong WK. Imaging features of hepatic sarcomatous carcinoma on computed tomography and gadoxetic acid-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2017;42:1424-1433. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Aghajanian C, Sill MW, Secord AA, Powell MA, Steinhoff M. Iniparib plus paclitaxel and carboplatin as initial treatment of advanced or recurrent uterine carcinosarcoma: a Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;126:424-427. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Song X, Li Y, Zhang H, Yang Q. The anticancer effect of Huaier (Review). Oncol Rep. 2015;34:12-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Chen Q, Shu C, Laurence AD, Chen Y, Peng BG, Zhen ZJ, Cai JQ, Ding YT, Li LQ, Zhang YB, Zheng QC, Xu GL, Li B, Zhou WP, Cai SW, Wang XY, Wen H, Peng XY, Zhang XW, Dai CL, Bie P, Xing BC, Fu ZR, Liu LX, Mu Y, Zhang L, Zhang QS, Jiang B, Qian HX, Wang YJ, Liu JF, Qin XH, Li Q, Yin P, Zhang ZW, Chen XP. Effect of Huaier granule on recurrence after curative resection of HCC: a multicentre, randomised clinical trial. Gut. 2018;67:2006-2016. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 22.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Qi T, Dong Y, Gao Z, Xu J. Research Progress on the Anti-Cancer Molecular Mechanisms of Huaier. Onco Targets Ther. 2020;13:12587-12599. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |