Published online Mar 6, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i7.2307

Peer-review started: September 21, 2021

First decision: October 22, 2021

Revised: November 6, 2021

Accepted: January 22, 2021

Article in press: January 22, 2022

Published online: March 6, 2022

Processing time: 161 Days and 16.5 Hours

Smoldering multiple myeloma (SMM) is an asymptomatic plasma cell proliferative disorder that can progress to multiple myeloma (MM). Amyloidosis (light chain) (AL) is the most common form of systemic amyloidosis. There are few reports of SMM coexisting with AL involving the digestive tract.

A 63-year-old woman presented with lower limb edema, abdominal distension, abdominal pain, and hematochezia. Gastroscopy showed gastric retention, gastric angler mucosal coarseness, hyperemia, and mild oozing of blood. Colonoscopy showed hyperemic and edematous mucosa of the distal ascending colon and sigmoid colon with the presence of multiple round and irregular ulcers, submucosal ecchymosis, and hematoma. Gastric and colonic tissue biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of AL by positive Congo red staining. MM was confirmed by bone marrow biopsy and immunohistochemistry. The patient had no hypercalcemia, renal dysfunction, anemia, bone lesions or biomarkers of malignancy defined as plasma cells > 60% in bone marrow. Additionally, no elevated serum free light chain ratio, or presence of bone marrow lesions by magnetic resonance imaging (SLiM criteria) were detected. The patient was finally diagnosed with SMM coexisting with AL. She received chemotherapy and was discharged when the symptoms were relieved. She is doing well at nearly five years of follow up.

This case highlights that high index of suspicion is required to diagnose gastrointestinal AL. It should be suspected in elderly patients with endoscopic findings of granular-appearing mucosa, ecchymosis, and submucosal hematoma. Timely diagnosis and appropriate therapy can help to improve the prognosis of these patients.

Core Tip: We report an unusual case of smoldering multiple myeloma with gastrointestinal symptoms (abdominal distension, abdominal pain, and blood in the stool). Gastrointestinal amyloidosis (light chain) (AL) was suspected based on the endoscopic findings of granular-appearing mucosa, ecchymosis, and submucosal hematoma. The diagnosis of gastrointestinal AL was confirmed by Congo red staining of biopsied tissues. The patient was doing well at the last follow-up of 5 years after chemotherapy which is the best prognosis among the reported cases of multiple myeloma with gastrointestinal AL.

- Citation: Liu AL, Ding XL, Liu H, Zhao WJ, Jing X, Zhou X, Mao T, Tian ZB, Wu J. Gastrointestinal amyloidosis in a patient with smoldering multiple myeloma: A case report . World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(7): 2307-2314

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i7/2307.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i7.2307

Amyloidosis is a clinical disorder of extracellular deposition of fibrillar proteins in one or more organs. More than 40 different types of proteins have been identified to form amyloid in humans. The most common protein found in amyloidosis is the light chain immunoglobulin. Amyloidosis (light chain) (AL) is the most common form of systemic amyloidosis, accounting for approximately 70% of all cases[1]. The monoclonal light chain (κ or λ) originates from the abnormal proliferation of bone marrow plasma cells[2]. Multiple myeloma (MM) is a hematologic malignancy characterized by uncontrolled proliferation of monoclonal plasma cells in the bone marrow. The common clinical manifestations of MM are bone pain, anemia, kidney injury, repeated infections, and extramedullary plasmacytoma[3]. When the patient is asymptomatic, it is called smoldering MM (SMM). Approximately 10%-15% of MM patients develop overt AL[4]. However, there are few reports of MM coexisting with gastrointestinal AL[4]. Moreover, there are only two reported cases of SMM combined with gastrointestinal AL to date[5,6]. Here, we report a case of an elderly woman with SMM and gastrointestinal AL who was successfully treated with chemotherapy.

A 63-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital in November 2016 due to pedal edema lasting four months, abdominal distension and abdominal pain for one month, and hematochezia for one week. She had no nausea, vomiting, fever or weight loss.

The patient had no history of malignancy.

This patient had no history of smoking or drinking, and no familial history of genetic diseases.

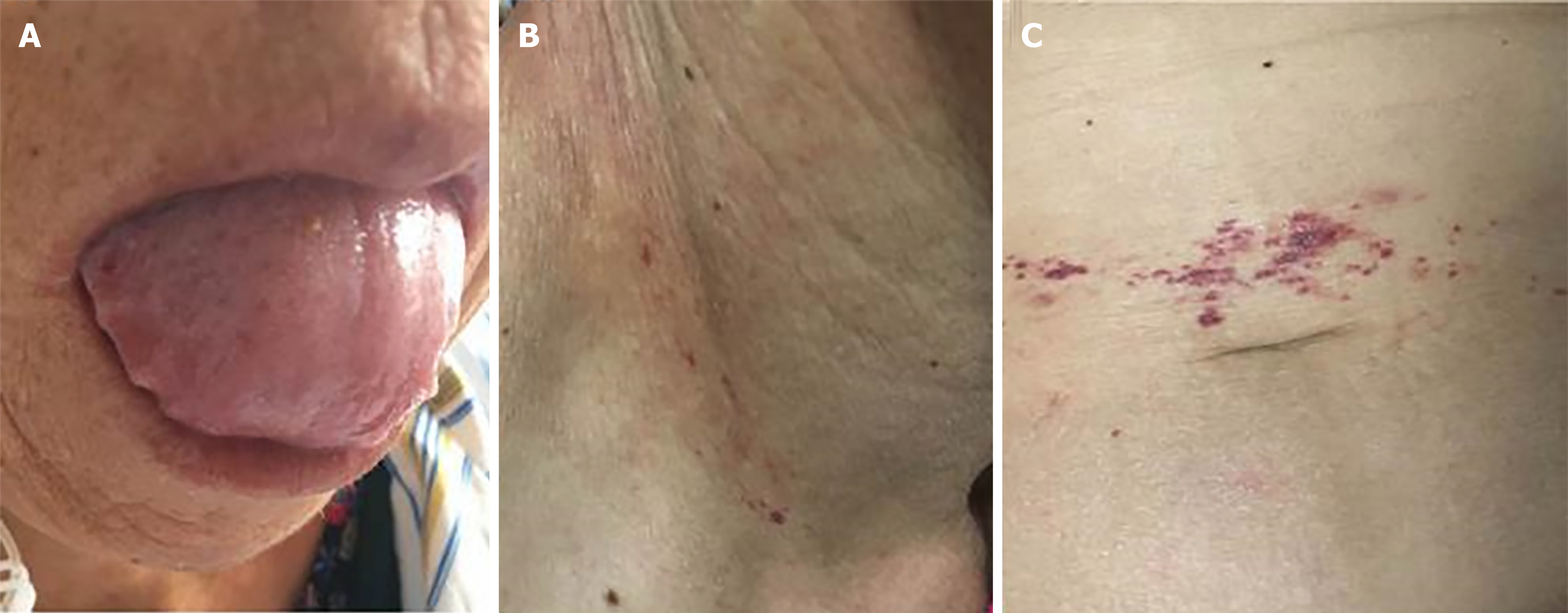

On physical examination, her tongue was swollen with teeth prints and skin purpura was present in the right neck and periumbilical region (Figure 1). There was mild edema in both lower extremities.

Laboratory investigations revealed normocytic anemia, hypoalbuminemia, and increased D-dimer. Stool occult blood was positive. Urinary kappa chain and lambda chain were elevated (Table 1). Serum protein electrophoresis and immunofixation were negative.

| Parameter | Patient value | Reference value |

| Hemoglobin | 94 g/L | 115-150 g/L |

| C-reactive protein | 3.03 mg/L | 0-5 mg/L |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate | 13 mm/h | 0-20 mm/h |

| D-dimer | 2170 ng/mL | 0-500 ng/mL |

| Serum albumin | 30.23 g/L | 40-55 g/L |

| Serum globulin | 20.20 g/L | 20-40 g/L |

| nt-proBNP | 381.8 pg/mL | 0-125 pg/mL |

| Serum calcium | 2.11 mmol/L | 2.11-2.52 mmol/L |

| Antinuclear antibodies | 1:100 | < 1:100 |

| ANCA | Negative | Negative |

| Serum immunoglobulin kappa chain | 1.77 g/L | 1.7-3.7g /L |

| Serum immunoglobulin lambda chain | 1.41 g/L | 0.9-2.1 g/L |

| Serum free lambda/kappa | < 100 | < 100 |

| Urinary kappa (κ) chain | 20.5 0 mg/L | 0-7.1 mg/L |

| Urinary lambda (λ) chain | 1110 mg/L | 0-3.9 mg/L |

| β2 microglobulin | 2216.58 ug/L | 900-2700 ug/L |

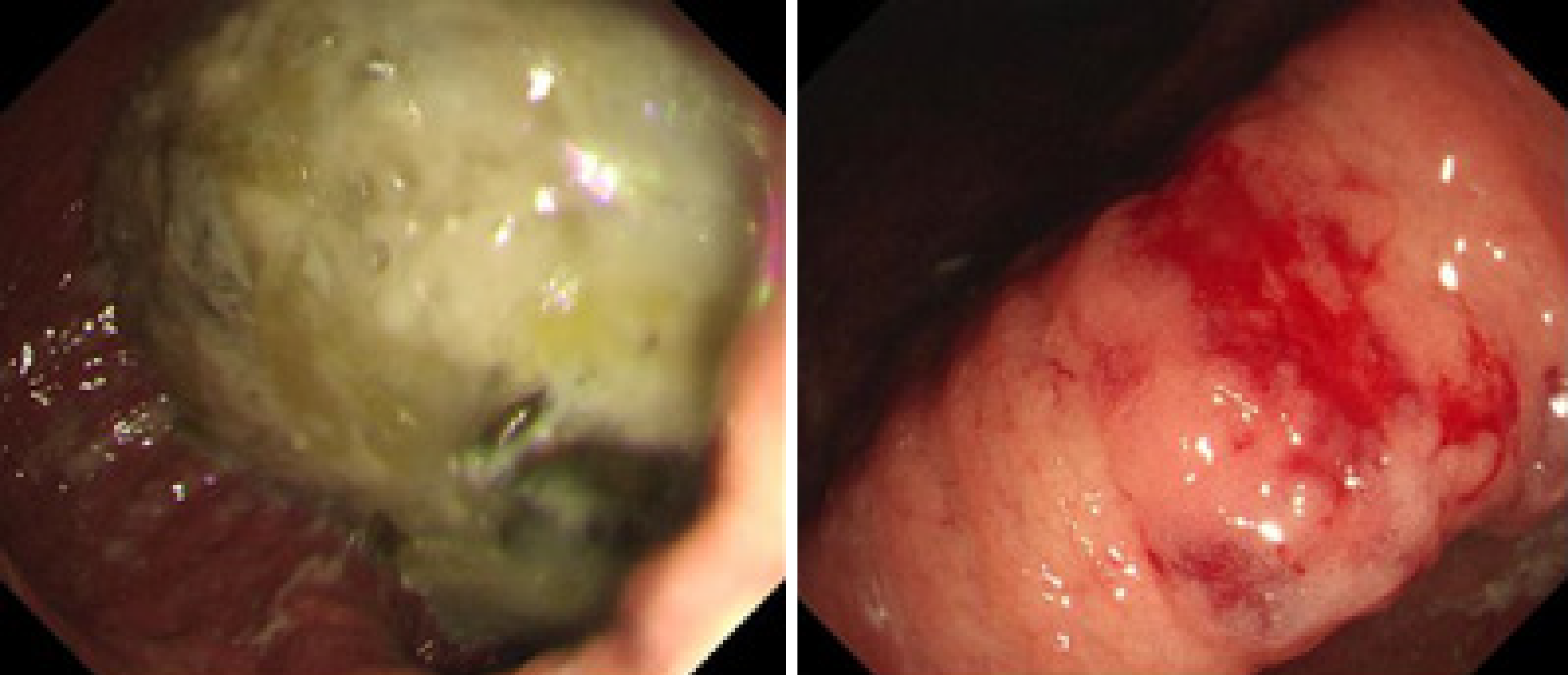

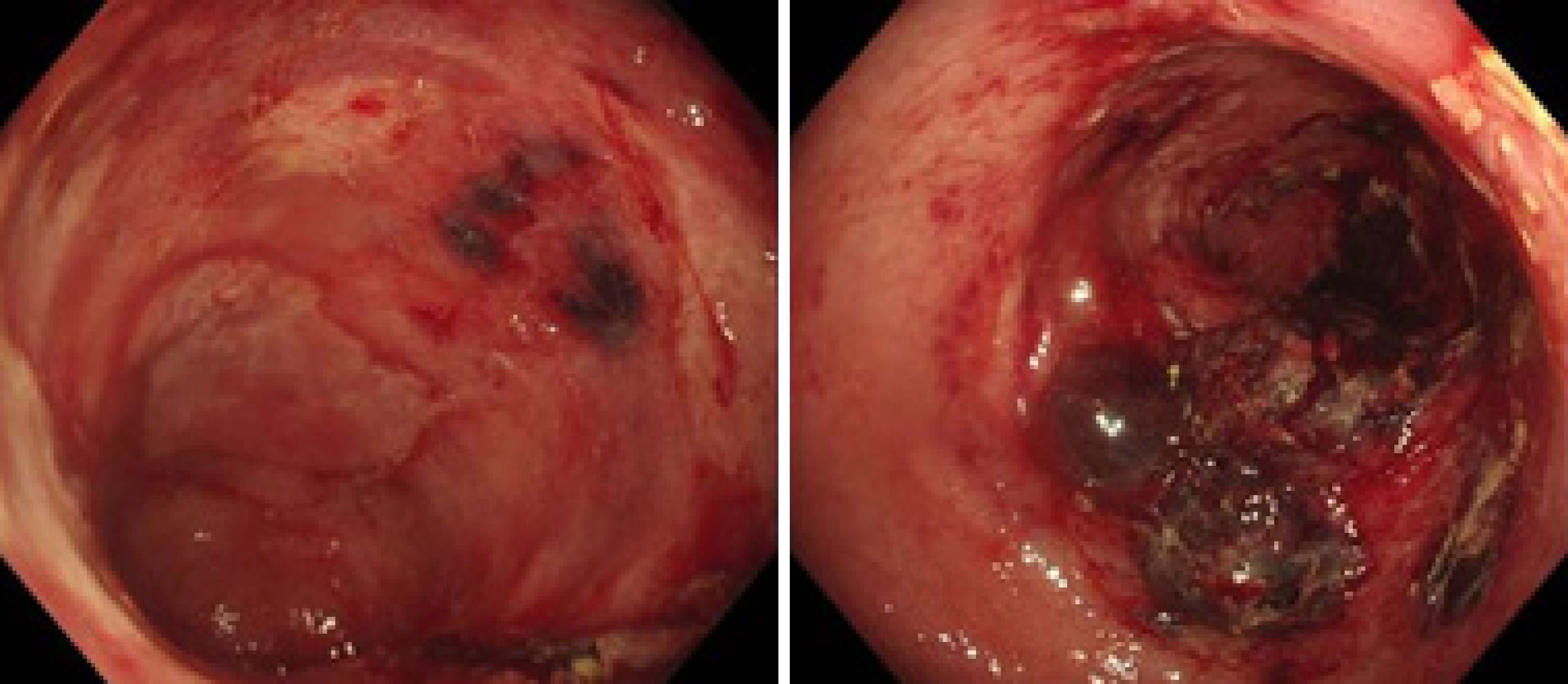

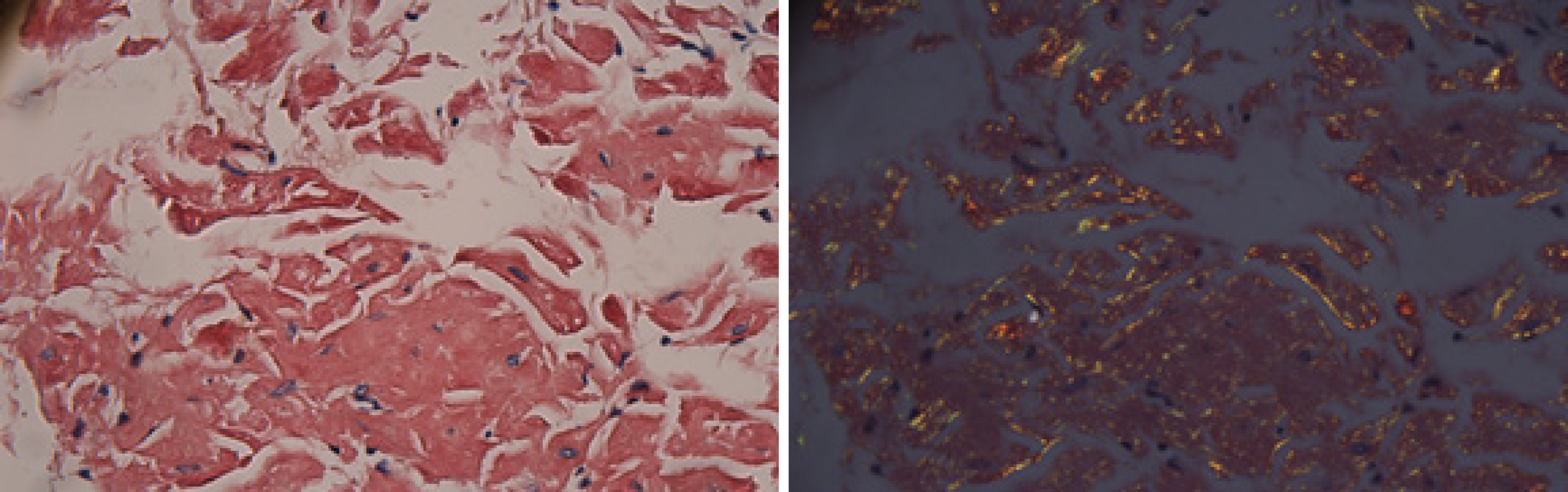

The electrocardiogram was normal. Echocardiography revealed normal left ventricular ejection fraction (61%) and slightly decreased left ventricular diastolic function. Computed tomography (CT) found marked thickening of the stomach and whole colon mild ascites, and pleural effusion. Doppler ultrasound revealed left lower limb venous thrombosis. Gastroscopy showed gastric retention, mucosal coarseness, hyperemia, and mild oozing of blood from the incisura angularis (Figure 2). Colonoscopy showed mucosal hyperemia, edema with multiple round and irregular ulcers, ecchymosis and hematoma in the distal descending and sigmoid colon (Figure 3). Histologic staining with Congo red stain (Figure 4) revealed positively staining deposits in the lamina propria of the gastric and colonic mucosa without plasmacytic infiltration. A bone marrow aspiration smear was hypocellular with reduced numbers of granulocytic and erythroid precursors in each stage. No gene mutation was tested. Bone marrow biopsy showed the presence of neoplastic plasma cells in small clusters accounting for 15%-20% of the marrow elements. Immunohistochemistry revealed lambda light chains in the neoplastic cells establishing the diagnosis of MM. X-rays of the head, lumbar spine, pelvis, and chest did not reveal any lytic lesions.

The patient was finally diagnosed as SMM with AL (λ subtype), involving tongue, skin, stomach and colon.

The patient was started on proton pump inhibitors and somatostatin which significantly reduced her gastrointestinal symptoms. Subsequently, she received one session of inpatient chemotherapy with vindesine, epirubicin and dexamethasone. Thalidomide was added to prevent angiogenesis. Low molecular heparin and warfarin were given for lower extremity venous thrombosis. Bacterial pneumonia developed during the treatment. However, the patient improved after anti-infective therapy. She was discharged after a hospital stay of one month when the symptoms of lower limb edema, abdominal distension and abdominal pain improved. Later, she received outpatient chemotherapy with hypodermic injection of bortezomib (2.2 mg) on days 1, 4, 8, and 11, and intravenous dexamethasone (40.5 mg) on days 1, 4, 8, and 11 every month for about 5 years. After 10 mo, the patient was improved. The hemoglobin level increased to 127 g/L, and β2 microglobulin, urinary kappa chain, and lambda chain returned to normal. Bone marrow biopsy revealed hyperplastic medullary images without neoplastic plasma cells.

The patient was regularly followed for roughly five years. During this period, the patient had occasional episodes of mild abdominal distension. The latest bone marrow biopsy in April 2021 showed that neoplastic plasma cells accounted for 20.5% of the marrow elements. Echocardiography revealed myocardial amyloidosis, suggesting progression of the disease. However, she is currently continuing chemotherapy and is doing well as of the last follow up in August 2021.

AL can be primary amyloidosis or secondary to myeloma. The proportion of λ and κ light chain is about 3:1[7]. The incidence of AL is estimated to be 3 to 5 per million per year. The mean age of onset is about 65 years. AL can affect multiple organs such as heart, kidney, liver, tongue, gastrointestinal tract, skin and nerves. The digestive system is affected in about 3.2% patients with amyloidosis of any type[8], and roughly 10% patients with AL[9]. The parts of digestive system most commonly affected are tongue, esophagus, stomach, small intestine, large intestine, liver, and spleen. The corresponding clinical manifestations include enlarged tongue, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea, hematochezia, abdominal distension, constipation, and hepatosplenomegaly. The complications include mesenteric infarction, intestinal obstruction, and intestinal perforation. In the index case, tongue (enlargement) and skin (purpura) were affected with AL. Abnormal gastric motility resulted in gastric retention. Colonic ulcers and hematoma led to hematochezia. She did not have myocardial amyloidosis until nearly 5 years later.

On endoscopy, gastrointestinal amyloidosis can mimic inflammatory bowel disease, ischemic colitis, and gastrointestinal tumors. Amyloidosis can appear as granular-appearing mucosa, polyps, erosions, ulcers, and submucosal hematomas[10]. The endoscopic manifestation of amyloidosis depends on the location and the amount of amyloid deposition. When a small amount of amyloid is deposited in the submucosa, the mucosal layer remains intact. As the amyloid deposition gradually increases, the elasticity of tissue decreases, the mucosa becomes erythematous with the development of erosions and ecchymosis. When there is abundant amyloid deposition, submucosal hematomas develop. After the absorption of hematoma, shallow ulcers and hyperplastic polypoidal lesions can be seen. When all layers of the intestinal wall are affected, fibroblast hyperplasia occurs which can cause intestinal stenosis and obstruction. The gastrointestinal bleeding from amyloidosis occurs due to local ischemia, infarction, and mucosal injury causing erosions, hematomas, and ulcerations. Gastrointestinal bleeding caused by submucosal hematoma can be obscure or overt, or sometimes life-threatening[5].

Amyloidosis is diagnosed by histological examination of tissue biopsies of the affected organs with Congo red staining and apple-green birefringence using polarized microscopy. It is necessary to identify the subtype and etiology of amyloidosis for treatment. In our case, AL was confirmed by positive Congo red staining of gastric and colonic tissues.

SMM is a transitional stage between monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance and MM. The diagnostic criteria of SMM are as follows[11]: monoclonal protein level ≥ 30 g/L , or 24 hr urine immunoglobulin light chain ≥ 0.5 g (or both), or 10%-60% clonal marrow plasmacytosis with the absence of end-organ damage and biomarkers of malignancy. The CRAB features of hypercalcemia, renal failure, anemia, and destructive bone lesions suggest end-organ failure. Biomarkers of malignancy (SLiM criteria) include plasma cells greater than 60% in the bone marrow, elevated serum free light chain ratio, and the presence of bone lesions on MRI[3]. In our patient, the urinary lambda (λ) chain was 1110 mg/L and the bone marrow biopsy showed neoplastic plasma cells accounting for 15%-20% of the marrow elements. Though our patient had anemia and occult blood in stools, the anemia improved once the gastrointestinal bleeding ceased. Therefore, the cause of anemia in the present case was gastrointestinal bleeding rather than bone marrow failure due to MM. Although the patient did not undergo MRI, the X-ray revealed no lytic lesions. Hence, the patient had no CRAB or SLiM criteria. The patient was finally diagnosed as AL secondary to SMM. A comprehensive literature search was conducted with publication dates from January 1, 1990, to August 31, 2021. There are only two reported cases of SMM combined with gastrointestinal AL (Table 2). Gjeorgjievski et al[5] reported a 92-year-old female with a history of SMM who presented with progressive fatigue, dizziness, and melena. Bone marrow biopsy showed numerous plasma cells with λ light chain on immunohistochemical staining. Endoscopy revealed an ulcerated mass in the gastric body. Tissue biopsy with positive Congo red staining was consistent with gastric AL(λ) amyloidosis. Gastrointestinal bleeding stopped when she was given intravenous omeprazole. However, the patient’s reported follow-up time (one month) was very short. Liyanaarachchi et al[6] reported a 51-year-old male who was admitted with nausea, vomiting, loss of weight, and haematemesis for 2 mo. Bone marrow aspiration and biopsy revealed hypercellular marrow with more than 30% plasma cells. Endoscopy showed an unhealthy oedematous mucosa with erosions and exposed blood vessels in the stomach and duodenum. He was diagnosed as SMM causing AL amyloidosis. The patient was given proton pump inhibitors. However, he rapidly deteriorated and succumbed to septic shock.

| Ref. | Gjeorgjievski et al[5], 2015 | Liyanaarachchi et al[6], 2017 |

| Age | 92 | 51 |

| Gender | Female | Male |

| M protein type | IgG lambda M-protein | IgG lambda M-protein |

| Symptoms | Weakness, lethargy, orthostatic dizziness, melena | Nausea, vomiting, loss of weight, haematemesis |

| Endoscopy | Ulcerated mass in the stomach | Oedematous mucosa with erosions and exposed blood vessels in the stomach and duodenum |

| Treatment | Omeprazole | Proton pump inhibitors |

| Follow-up time | One month | None |

| Prognosis | No bleeding | Succumbed to septic shock |

The overall risk of progression of SMM to MM is about 10% per year in the first 5 years, 3% per year in the next 5 years and 1% per year thereafter[12]. SMM does not require active treatment as the end-organ damage is absent. Therapy of AL includes traditional chemotherapy (melphalan, prednisone), novel drugs such as protease inhibitors (bortezomib), immunosuppressants (thalidomide, lenalidomide) and autologous stem cell transplantation[7]. The treatment of amyloidosis-induced bleeding is difficult. Proton pump inhibitors and somatostatin maybe effective. Endoscopic injection of noradrenaline at the bleeding site can be performed but is often ineffective. Surgical intervention may be required for refractory bleeding for localized lesions[13]. Our patient did not have recurrent bleeding after proton pump inhibitors and somatostatin therapy. She then received chemotherapy and was discharged when the symptoms were relieved.

The prognosis of gastrointestinal amyloidosis is poor, and mainly depends on the underlying disease and organ involvement. In a study of 155 patients with systemic amyloidosis, 24 patients had gastrointestinal involvement and 131 patients had no gastrointestinal involvement[14]. Median overall survival in patients with gastrointestinal involvement was shorter (8 mo) than in those without gastrointestinal involvement (16 mo). Our patient has survived for nearly five years after diagnosis. As far as we know, the index case has the longest follow-up and the best prognosis among reported cases of MM and gastrointestinal AL. The good outcome of our patient was probably due to early diagnosis and absence of organ involvement other than the digestive tract.

In summary, we report a rare case of SMM with gastrointestinal AL achieving long-term survival of about 5 years with medical therapy. Gastrointestinal amyloidosis should be considered in elderly patients with endoscopic findings of granular-appearing mucosa, ecchymosis, and submucosal hematoma. Once amyloidosis is diagnosed, further evaluation should be carried out to distinguish between primary and secondary amyloidosis, identify the subtype of amyloidosis, and determine the organ involvement. Timely diagnosis and treatment can help to improve the prognosis.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Ahmed S, Yang T S-Editor: Xing YX L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Palladini G, Merlini G. What is new in diagnosis and management of light chain amyloidosis? Blood. 2016;128:159-168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 18.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Xiao H, Qing D, Li C, Zhou H. A case report of gastric amyloidosis due to multiple myeloma mimicking gastric cancer. BMC Gastroenterol. 2020;20:219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Brigle K, Rogers B. Pathobiology and Diagnosis of Multiple Myeloma. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2017;33:225-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 15.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hu H, Huang D, Ji M, Zhang S. Multiple myeloma with primary amyloidosis presenting with digestive symptoms: A case report and literature review. Arab J Gastroenterol. 2020;21:54-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Gjeorgjievski M, Purohit T, Amin MB, Kurtin PJ, Cappell MS. Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding from Gastric Amyloidosis in a Patient with Smoldering Multiple Myeloma. Case Rep Gastrointest Med. 2015;2015:320120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Liyanaarachchi LATM, Kalubowila U, Ratnayake RMCSB, Ratnayake NVI, Ratnatunga RMP, Rathnayake. Light-chain amyloidosis (AL amyloidosis) presenting as gastrointestinal bleeding. J Postgraduate Institute Med. 2017;4:41. |

| 7. | Hasib Sidiqi M, Gertz MA. Immunoglobulin light chain amyloidosis diagnosis and treatment algorithm 2021. Blood Cancer J. 2021;11:90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Cowan AJ, Skinner M, Seldin DC, Berk JL, Lichtenstein DR, O'Hara CJ, Doros G, Sanchorawala V. Amyloidosis of the gastrointestinal tract: a 13-year, single-center, referral experience. Haematologica. 2013;98:141-146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Singh K, Chapalamadugu P, Malet P. Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding Due to Amyloidosis in a Patient With Multiple Myeloma. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:A22-A23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Liu YP, Jiang WW, Chen GX, Li YQ. Case report and review of the literature of primary gastrointestinal amyloidosis diagnosed with enteroscopy and endoscopic ultrasonography. World J Clin Cases. 2018;6:284-290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Mateos MV, Kumar S, Dimopoulos MA, González-Calle V, Kastritis E, Hajek R, De Larrea CF, Morgan GJ, Merlini G, Goldschmidt H, Geraldes C, Gozzetti A, Kyriakou C, Garderet L, Hansson M, Zamagni E, Fantl D, Leleu X, Kim BS, Esteves G, Ludwig H, Usmani S, Min CK, Qi M, Ukropec J, Weiss BM, Rajkumar SV, Durie BGM, San-Miguel J. International Myeloma Working Group risk stratification model for smoldering multiple myeloma (SMM). Blood Cancer J. 2020;10:102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 162] [Article Influence: 32.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kyle RA, Remstein ED, Therneau TM, Dispenzieri A, Kurtin PJ, Hodnefield JM, Larson DR, Plevak MF, Jelinek DF, Fonseca R, Melton LJ 3rd, Rajkumar SV. Clinical course and prognosis of smoldering (asymptomatic) multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2582-2590. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 609] [Cited by in RCA: 626] [Article Influence: 34.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Yeh YC, Lin CH, Huang SC, Tsou YK. Education and imaging. Gastrointestinal: gastric hematoma with bleeding in a patient with primary amyloidosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29:419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lim AY, Lee JH, Jung KS, Gwag HB, Kim DH, Kim SJ, Lee GY, Kim JS, Kim HJ, Lee SY, Lee JE, Jeon ES, Kim K. Clinical features and outcomes of systemic amyloidosis with gastrointestinal involvement: a single-center experience. Korean J Intern Med. 2015;30:496-505. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |