Published online Mar 6, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i7.2301

Peer-review started: September 29, 2021

First decision: December 2, 2021

Revised: December 13, 2021

Accepted: January 19, 2022

Article in press: January 19, 2022

Published online: March 6, 2022

Processing time: 153 Days and 17.1 Hours

Leishmaniasis includes a range of chronic infections in humans and animals and can be caused by more than 20 species of Leishmania protozoa. The manifestations of leishmaniasis are diverse and dependent on the immune response capacity of the host and the type of Leishmania. In East Asia, leishmaniasis is relatively rare and prone to misdiagnosis and underdiagnosis.

We report a case of a 36-year-old male with cutaneous leishmaniasis. The patient had been misdiagnosed with a bacterial skin infection and was given a dressing change and oral levofloxacin, which proved ineffective. Histopathological examination revealed amastigote (Leishman-Donovan body) in the histocytes, and nucleic acid sequencing proved that the pathogen was Leishmania major. The patient was treated successfully by regional injection of sodium gluconate (600 mg) three times. The ulcer healed and did not recur at 1.5-year follow-up.

Skin ulcers caused by leishmaniasis are easily misdiagnosed in non-epidemic countries, yet it should not be overlooked.

Core Tip: Cutaneous leishmaniasis is caused by Leishmania protozoan infection. The most common vector is the sandfly. It often presents as ulcerative plaques and nodules on exposed skin. Because cutaneous leishmaniasis is rare in East Asia, it is often misdiagnosed and underdiagnosed. We hope that this case will draw the attention of clinicians and increase the knowledge of differential diagnosis of skin ulcers.

- Citation: Zhuang L, Su J, Tu P. Cutaneous leishmaniasis presenting with painless ulcer on the right forearm: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(7): 2301-2306

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i7/2301.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i7.2301

Leishmaniasis is a chronic zoonotic parasitic disease caused by Leishmania protozoa infection with the main vector being sandflies[1]. There are four main types of leishmaniasis: cutaneous leishmaniasis, cutaneous mucosal leishmaniasis, visceral leishmaniasis and post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis. More than 90% of cutaneous leishmaniasis occurs in the Middle East and South America; the rest are found in North Africa, Central Asia and India. It is rare in East Asia (China, Japan, Korea, North Korea, etc.)[2]. Cutaneous leishmaniasis occurs in exposed skin areas susceptible to sandfly bites and presents as a papule that gradually expands into an ulcerative plaque. Because cutaneous leishmaniasis is rare in East Asia, it is more likely to be misdiagnosed and underdiagnosed and requires the attention of clinicians.

A 36-year-old male presented with a painless ulcer on the right forearm lasting for 2 mo.

The patient had been working in central Asia for several years. He returned to China after noticing a soybean-sized nodule that gradually increased in size to an ulcer over a period of 2 mo on the right forearm. He was initially diagnosed with a bacterial skin infection, but the treatment of debridement and levofloxacin (0.5 g/d orally for 7 d) was unsuccessful.

The patient was in good health and had no history of other diseases.

The patient had been working in central Asia for 3 years. Family history was unremarkable.

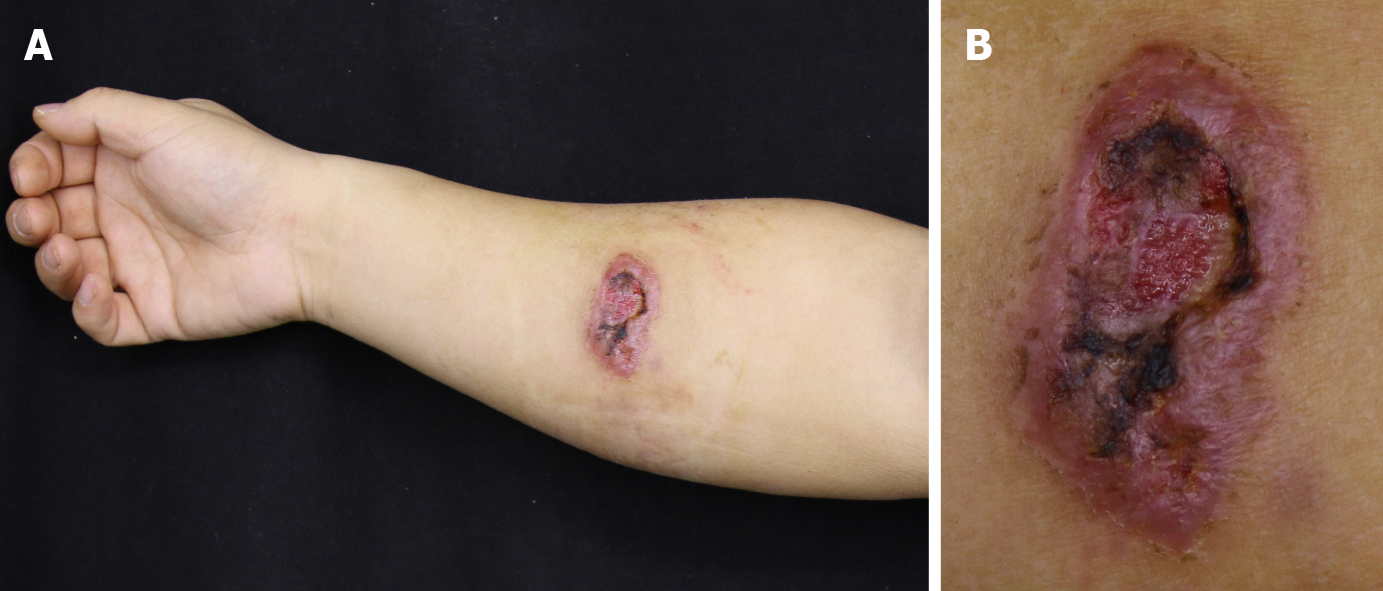

A 5.8 cm × 4.0 cm ulcer on the right forearm with black crust in the center and raised borders was observed. After squeezing, a clear, thin liquid secretion appeared. Three hard, peanut-sized subcutaneous nodules could be palpated around the ulcer (Figure 1A and B). No enlargement of lymph nodes was palpable in the right axilla or other areas.

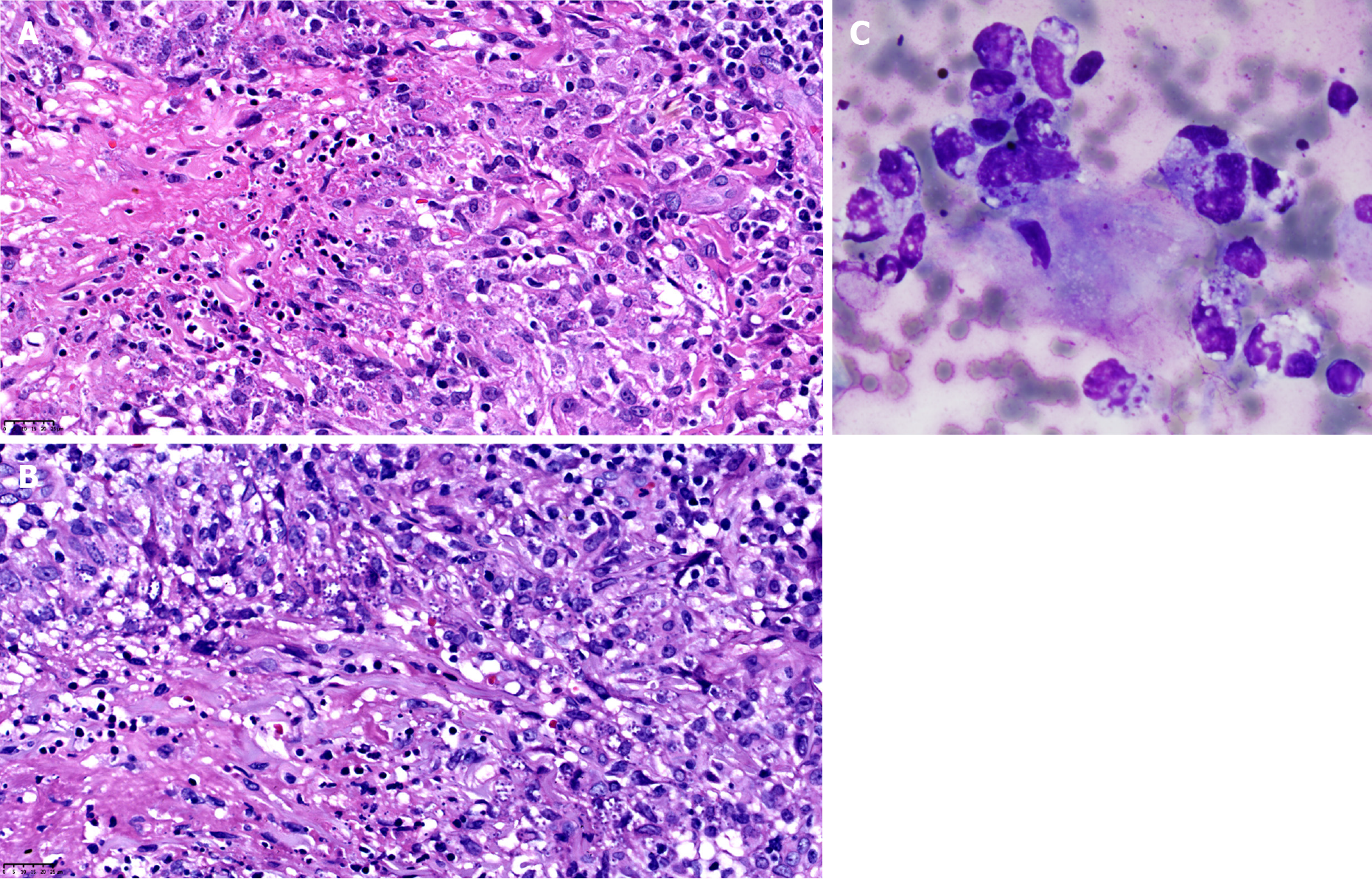

The results from routine tests, such as blood, urine, stool routine, liver and kidney function and bacterial culture, were normal. Histopathological examination revealed diffuse mixed inflammatory cell infiltration within the superficial and deep layers of the dermis. Amastigote of Leishmania existed in the cytoplasm of the histocytes (Figure 2A). Giemsa staining showed the amastigote more clearly (Figure 2B). Leishman-Donovan bodies were seen on scrapings of the skin lesion (Figure 2C), and no Leishman-Donovan bodies were seen on bone marrow smears. Serum immunoglobulin G antibody test of Leishmania donovani was negative.

Computed tomography examination of the chest and abdomen showed no abnormalities.

Combined with the clinical manifestations, histopathological changes and laboratory findings, visceral leishmaniasis could be excluded, and the diagnosis of cutaneous leishmaniasis was established. Since the patient had worked abroad for a long time and China was not a Leishmania major epidemic area, this case was consistent with imported cutaneous leishmaniasis.

Sodium gluconate (600 mg) topical injection into the lesions was administered once a week for 3 wk. The ulcer gradually shrank, and the subcutaneous nodules regressed significantly.

After treatment with antimony sodium gluconate, the lesion completely faded and left a scar. No recurrence was observed after 1.5 years of follow-up (Figure 3).

Cutaneous leishmaniasis, also known as oriental sore, occurs in the Middle East, Central Asia, India, North Africa and European countries along the Mediterranean Sea. Cases in non-endemic countries usually have a history of travel to the epidemic areas[2]. A variety of Leishmania species can cause cutaneous leishmaniasis, including Leishmania braziliensis, Leishmania mexicana, Leishmania amazonensis, Leishmania panamensis and Leishmania guynaesis in South America and Leishmania major, Leishmania tropicalis and Leishmania infantum in Asia, Africa and Europe[1]. The difference in virulence between different species is mainly due to the difference in lipophosphate glycans on the surface of Leishmania protozoa, which play an important role in the infection of the sandfly and the invasion of human macrophages[3].

The lesions of cutaneous leishmaniasis occur on exposed areas, such as the face, neck and extremities, that are susceptible to sandfly bites. In some patients with immunodeficiency, the lesions may disseminate or distribute along lymphatic vessels[4]. In most cutaneous leishmaniasis cases, the lesions may heal spontaneously with scarring within a few months, and some patients develop chronic or disseminated infections. It is important to note that leishmaniasis from South American species has a more diverse clinical presentation, is prone to disseminated and diffuse forms, and has a slightly worse prognosis than leishmaniasis from Asian, African and European species[2].

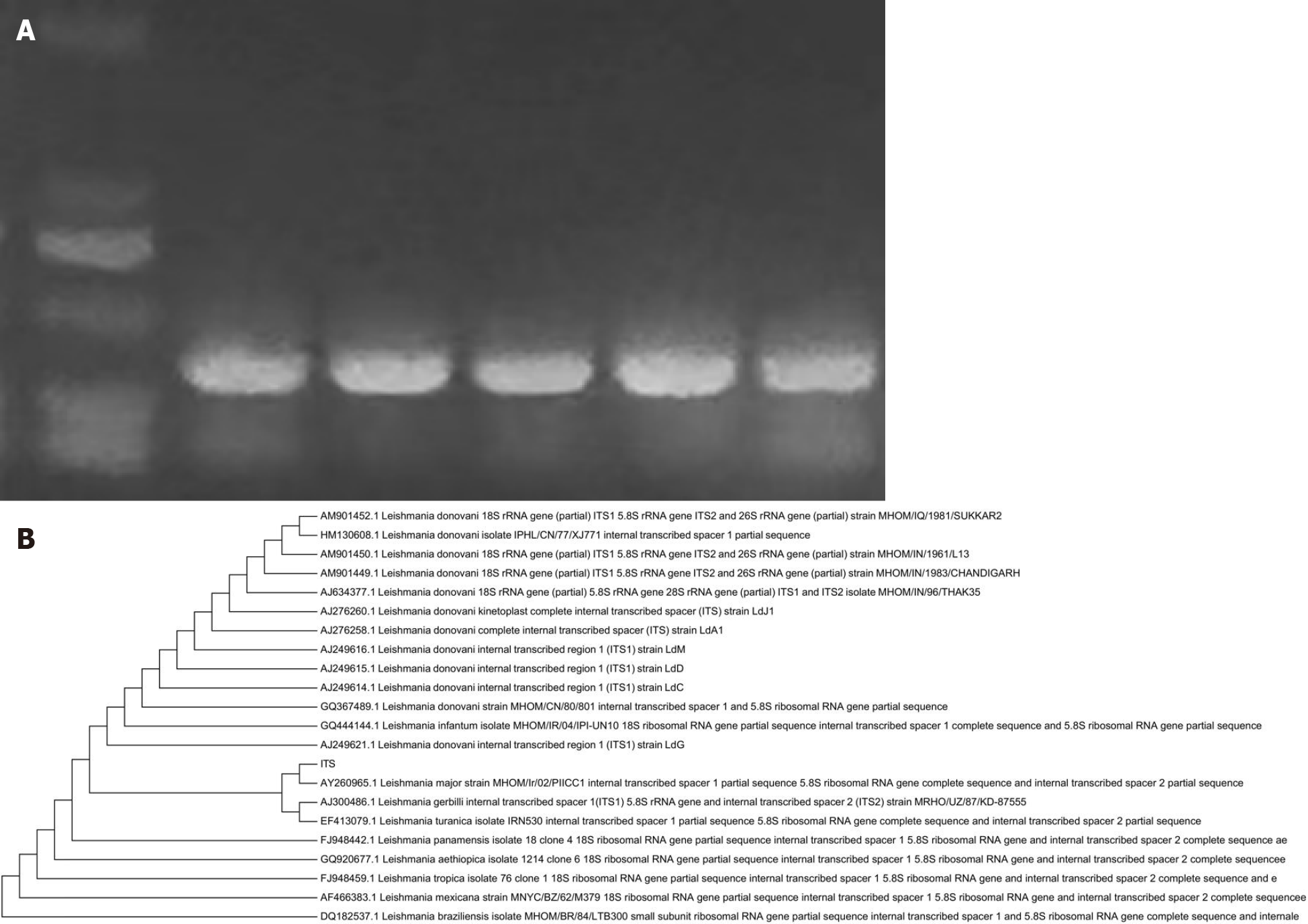

The diagnosis of cutaneous leishmaniasis relies on laboratory tests. In hematoxylin and eosin sections and smears of secretions, the use of Giemsa stain clearly shows the absence of amastigote and is an important basis for confirming the diagnosis[5]. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays, especially sequencing of PCR products, are commonly used to determine the specific infecting species. Leishmania protozoa belong to the kinetoplastida, whose kinetoplast DNA K13A and the transcribed spacer region ITS1 within the ribosomal DNA are highly conserved within species and differ between species[6,7]. Therefore, primers are often designed in this region for PCR amplification and sequencing (Figure 4). Due to the large variation in specificity and sensitivity, serological diagnostic methods have some application in visceral leishmaniasis but are rarely used for the diagnosis of cutaneous leishmaniasis[8]. In addition, some scholars are investigating the feasibility of worm antigens and specific proteins in the saliva of the vector whitefly as indicators of infection, and mouse animal models have demonstrated that host interleukin-10 levels correlate with disease severity[9].

In our case, the patient had a history of living abroad in central Asia, and the pathogenic examination revealed Leishmania major infection. We excluded the mucosa and visceral involvement, so the final diagnosis of cutaneous leishmaniasis was made.

Treatment selection for cutaneous leishmaniasis should be based on patients’ personal characteristics[10]. Some lesions may heal on their own or by local antimonial therapy within several months. For lesions with a diameter larger than 5 cm with local enlarged lymph nodes or that involve the face, auricle or genital area, the systematic antimonial treatment is needed[11,12]. Other drugs, such as amphotericin B, miltefosine, pentamidine and fluconazole, could be an option for patients who are intolerant to antimonials due to the adverse side effects[13,14]. In the future, it is expected that leishmaniasis will be radically cured by vaccination[15]. The lesion of our patient was solitary and confined to the forearm. Therefore, the intralesional injection of antimonials was provided, and the patient recovered well.

Cutaneous leishmaniasis in non-epidemic countries tends to be misdiagnosed as deep fungal infection, pyoderma gangrenosum, basal cell carcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma, which also present as ulcerative lesions and proliferative plaques. If a patient has a travel history to epidemic countries and skin lesions exist on the exposed skin areas, then leishmaniasis should be considered. Cutaneous leishmaniasis is somewhat self-healing, and treatment plans need to be tailored to the condition.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Dermatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Ferreira GSA, Tanabe H S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Burza S, Croft SL, Boelaert M. Leishmaniasis. Lancet. 2018;392, 951-970. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 954] [Cited by in RCA: 1292] [Article Influence: 184.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Handler MZ, Patel PA, Kapila R, Al-Qubati Y, Schwartz RA. Cutaneous and mucocutaneous leishmaniasis: Differential diagnosis, diagnosis, histopathology, and management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:911-26; 927. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sacks D, Kamhawi S. Molecular aspects of parasite-vector and vector-host interactions in leishmaniasis. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2001;55:453-483. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 272] [Cited by in RCA: 259] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Choi CM, Lerner EA. Leishmaniasis as an emerging infection. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2001;6:175-182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Andrade-Narvaez FJ, Medina-Peralta S, Vargas-Gonzalez A, Canto-Lara SB, Estrada-Parra S. The histopathology of cutaneous leishmaniasis due to Leishmania (Leishmania) mexicana in the Yucatan peninsula, Mexico. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2005;47:191-194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Weigle KA, Labrada LA, Lozano C, Santrich C, Barker DC. PCR-based diagnosis of acute and chronic cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania (Viannia). J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:601-606. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Yang BB, Guo XG, Hu XS, Zhang JG, Liao L, Chen DL, Chen JP. Species discrimination and phylogenetic inference of 17 Chinese Leishmania isolates based on internal transcribed spacer 1 (ITS1) sequences. Parasitol Res. 2010;107:1049-1065. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Elmahallawy EK, Sampedro Martinez A, Rodriguez-Granger J, Hoyos-Mallecot Y, Agil A, Navarro Mari JM, Gutierrez Fernandez J. Diagnosis of leishmaniasis. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2014;8:961-972. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Carrillo E, Moreno J. Editorial: Biomarkers in Leishmaniasis. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2019;9:388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Brito NC, Rabello A, Cota GF. Efficacy of pentavalent antimoniate intralesional infiltration therapy for cutaneous leishmaniasis: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0184777. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hepburn NC. Cutaneous leishmaniasis: an overview. J Postgrad Med. 2003;49:50-54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lawn SD, Whetham J, Chiodini PL, Kanagalingam J, Watson J, Behrens RH, Lockwood DN. New world mucosal and cutaneous leishmaniasis: an emerging health problem among British travellers. QJM. 2004;97:781-788. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Singh N, Kumar M, Singh RK. Leishmaniasis: current status of available drugs and new potential drug targets. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2012;5:485-497. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 258] [Cited by in RCA: 263] [Article Influence: 20.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Alrajhi AA, Ibrahim EA, De Vol EB, Khairat M, Faris RM, Maguire JH. Fluconazole for the treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania major. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:891-895. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 228] [Cited by in RCA: 204] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Launois P, Tacchini-Cottier F, Kieny MP. Cutaneous leishmaniasis: progress towards a vaccine. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2008;7:1277-1287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |