Published online Mar 6, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i7.2286

Peer-review started: September 13, 2021

First decision: November 22, 2021

Revised: November 24, 2021

Accepted: January 22, 2022

Article in press: January 22, 2022

Published online: March 6, 2022

Processing time: 170 Days and 2 Hours

Burkholderia gladioli (B. gladioli) is regarded as a rare opportunistic pathogen. Only a few patients with abscesses caused by B. gladioli infections have been reported, and these are usually abscesses at the incision caused by traumatic surgery.

A 74-year-old male patient with abscesses and pain throughout his body for 1 mo was admitted to our hospital. Some of the abscesses had ruptured with purulent secretions on admission. Color Doppler ultrasound examination of the body surface masses showed mixed masses 75 mm × 19 mm, 58 mm × 17 mm, 17 mm × 7 mm, and 33 mm × 17 mm in size in the muscle tissues of both the right and left forearms, the posterior area of the right knee and the left leg, respectively. Abscess secretions and blood cultures grew B. gladioli. The following 3 methods were used to jointly identify the bacterium: an automatic microbial identification system, matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry, and full-length 16S rDNA sequencing. After 27 d of treatment with meropenem, etimicin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and other antibiotics, most of his skin abscesses were flat and he was discharged without any symptoms.

This is the first reported case of multiple skin abscesses associated with bacteremia caused by B. gladioli. Our study provides important reference values for the clinical diagnosis and treatment of B. gladioli infections.

Core Tip: Burkholderia gladioli (B. gladioli) is a rare opportunistic pathogen. We report the first case of multiple skin abscesses caused by infection due to B. gladioli, and the relevant biological information, identification, and sensitivity to drugs, are also described in detail. The following three methods including an automatic microbial identification system, matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry, and full-length 16S rDNA sequencing were jointly used to identify this bacterium. Therefore, the results obtained using the combination of these methods, were more accurate and reliable. This case provides a solid basis for the future clinical diagnosis and treatment of B. gladioli infections.

- Citation: Wang YT, Li XW, Xu PY, Yang C, Xu JC. Multiple skin abscesses associated with bacteremia caused by Burkholderia gladioli: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(7): 2286-2293

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i7/2286.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i7.2286

Burkholderia gladioli (B. gladioli) belongs to the genus Burkholderia, which is a group of Gram-negative, aerobic, and non-fermentative bacteria. They were originally identified as plant pathogens in gladiolus and other flowers, and most of them were isolated from soil or water samples. In general, B. gladioli is an uncommon opport

A 74-year-old male patient suffering from abscesses and pain throughout his body for 1 mo was admitted to the First Hospital of Jilin University on June 3, 2021.

The patient did not have a fever, cough, or abdominal pain during the disease. On admission, the skin on his left anterior chest, abdomen, and limbs showed red abscesses, which ranged in size from a broad bean to that of an egg. Some of the abscesses had ruptured with purulent secretions and obvious tenderness. Deep ulcers the size of 3 eggs were observed on his right upper limb and left lower limb. Furthermore, the ulcers in his right forearm even reached the muscular layer. Petechiae the size of millet grains or beans, were scattered around his lower limbs, with no signs of fading.

The patient suffered from left mandibular lymph node enlargement and underwent surgical incision and drainage 4 mo ago. The patient was hospitalized due to pneumonia 3 years ago.

The patient had no relevant personal and family history.

Physical examination showed the following: Body temperature was 36.5oC, pulse rate was 70 bpm, respiratory rate was 20 breaths/min, and blood pressure was 115/54 mmHg.

The initial laboratory examinations on admission showed the following levels: white blood cell (WBC) count was 41.96 × 109/L, neutrophil absolute value (NE) was 37.64 × 109/L, monocyte absolute value was 2.16 × 109/L, red blood cell count was 2.93 × 1012/L, hemoglobin was 80 g/L, hematocrit was 0.266 L/L, red blood cell distribution width was 24.8%, and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein was 170.26 mg/L.

Color Doppler ultrasound examinations of the body surface masses on admission showed mixed masses 75 mm × 19 mm, 58 mm × 17 mm, 17 mm × 7 mm, and 33 mm × 17 mm in size in the muscle tissues of both the right and left forearms, the posterior area of the right knee and the left leg, respectively.

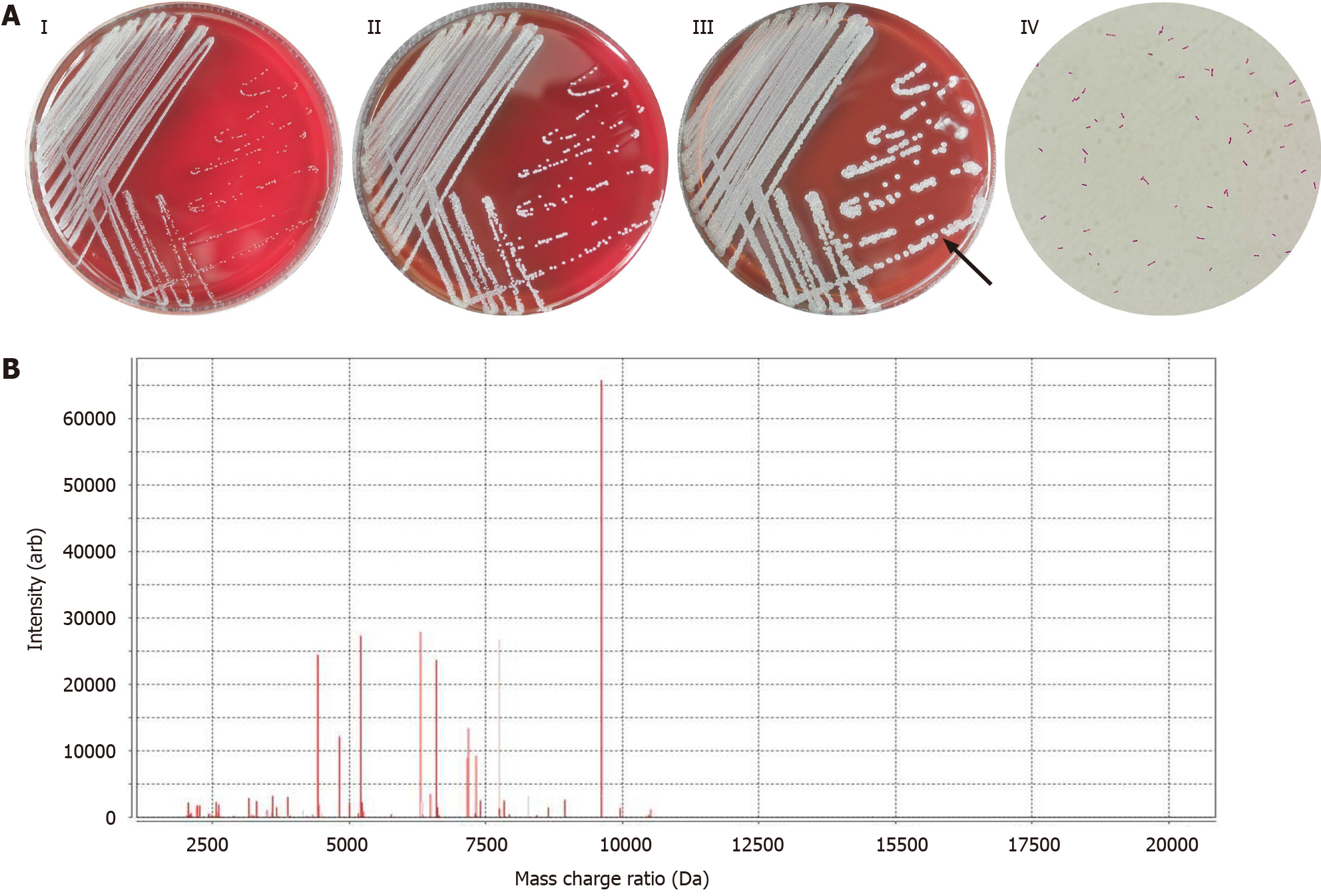

The patient’s abscess secretions on admission day 2 and 5 were collected and cultured for general bacteria/fungi at 35oC with 5% CO2. The bacterial culture showed positive results after 24 h, and no fungi were identified even after 72 h. The bacteria were inoculated into sheep blood and MacConkey agar plates at 37oC. After 36 h, yellowish, round, smooth, moist, slightly raised, and neatly edged colonies appeared on the plates. The bacteria showed a short-rod shape, arranged singly or in pairs under the microscope, and were identified as Gram-negative bacteria based on Gram staining results. Biochemical analysis showed positive results for catalase and dynamic tests, and negative for oxidase and H2S tests. On admission day 2 and 9, the patient’s blood was added to BACT/ALERT FN Plus Aerobic/F and Anaerobic/F media, respectively, and was cultured in a BACT/ALERT VIRTUO automatic blood culture system. The results of Aerobic/F blood cultures were positive after 36 h, and the colony characteristics, microscopic morphology, and biochemical reactions of this bacterium were consistent with the result of pus cultures, and the results of Anaerobic/F blood cultures were negative. Blood cultures were performed again on admission day 26. The results of Aerobic/F and Anaerobic/F blood cultures were negative after 72 h. The colony and microscopic morphology of B. gladioli are shown in Figure 1A.

In addition, the following 3 methods were used to jointly identify the bacterium in abscess secretions and blood: (1) The VITEK 2 GN cards in the VITEK 2 XL automatic microbial identification system were used for identification (98% probability), and after 4.78 h of analysis, B. gladioli was identified; (2) VITEK MS mass spectrometry (99.9% probability) and MALDI-TOF-MS technology were used to identify the bacterium as B. gladioli, and relevant results of the mass spectrogram are shown in Figure 1B; and (3) Full-length 16S rDNA sequencing was also used to identify this bacterium, and the primers 7F 1540R and 27F 1492R were used for the amplification of 16S rRNA. The PCR products were purified using the SK8255 Ezup column bacterial genomic DNA extraction kit and the sequence was determined by the Applied Biosystems 3730XL sequencer. The Ribosomal Database Project database was applied for similarity alignment against the sequence of this bacterium (NCBI Accession No. DQ513513). The sequence determination results were as follows: the length of the sequence was 1441 bp, the sequence similarity was 99% between this bacterium and B. gladioli. The detailed sequence was as follows: TGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAGATTGAACGCTGGCGGCATGCCTTACACATGCAAGTCGAACGGCAGCACGGGTGCTTGCACCTGGTGGCGAGTGGCGAACGGGTGAGTAATACATCGGAACATGTCCTGTAGTGGGGGATAGCCCGGCGAAAGCCGGATTAATACCGCATACGATCTACGGATGAAAGCGGGGGACCTTCGGGCCTCGCGCTATAGGGTTGGCCGATGGCTGATTAGCTAGTTGGTGGGGTAAAGGCCCACCAAGGCGACGATCAGTAGCTGGTCTGAGAGGACGACCAGCCACACTGGGACTGAGACACGGCCCAGACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAGTGGGGAATTTTGGACAATGGGCGAAAGCCTGATCCAGCAATGCCGCGTGTGTGAAGAAGGCCTTCGGGTTGTAAAGCACTTTTGTCCGGAAAGAAATCCTGAGGGCTAATATCCTTCGGGGATGACGGTACCGGAAGAATAAGCACCGGCTAACTACGTGCCAGCAGCCGCGGTAATACGTAGGGTGCGAGCGTTAATCGGAATTACTGGGCGTAAAGCGTGCGCAGGCGGTTTGTTAAGACCGATGTGAAATCCCCGGGCTCAACCTGGGAACTGCATTGGTGACTGGCAAGCTAGAGTATGGCAGAGGGGGGTAGAATTCCACGTGTAGCAGTGAAATGCGTAGAGATGTGGAGGAATACCGATGGCGAAGGCAGCCCCCTGGGCCAATACTGACGCTCATGCACGAAAGCGTGGGGAGCAAACAGGATTAGATACCCTGGTAGTCCACGCCCTAAACGATGTCAACTAGTTGTTGGGGATTCATTTCCTTAGTAACGTAGCTAACGCGTGAAGTTGACCGCCTGGGGAGTACGGTCGCAAGATTAAAACTCAAAGGAATTGACGGGGACCCGCACAAGCGGTGGATGATGTGGATTAATTCGATGCAACGCGAAAAACCTTACCTACCCTTGACATGGTCGGAATCCTGGAGAGATCTGGGAGTGCTCGAAAGAGAACCGATACACAGGTGCTGCATGGCTGTCGTCAGCTCGTGTCGTGAGATGTTGGGTTAAGTCCCGCAACGAGCGCAACCCTTGTCCTTAGTTGCTACGCAAGAGCACTCTAGGGAGACTGCCGGTGACAAACCGGAGGAAGGTGGGGATGACGTCAAGTCCTCATGGCCCTTATGGGTAGGGCTTCACACGTCATACAATGGTCGGAACAGAGGGTCGCCAACCCGCGAGGGGGAGCTAATCCCAGAAAACCGATCGTAGTCCGGATTGCACTCTGCAACTCGAGTGCATGAAGCTGGAATCGCTAGTAATCGCGGATCAGCATGCCGCGGTGAATACGTTCCCGGGTCTTGTACACACCGCCCGTCACACCATGGGAGTGGGTTTTACCAGAAGTGGCTAGTCTAACCGCAAGGAGGA. The above three methods were combined to identify the bacterium as B. gladioli. The instruments and reagents used in full-length 16S rDNA sequencing were from Sangon Biotech Shanghai Co., Ltd. Instruments and reagents used in other methods were derived from BioMérieux (Lyon, France).

The Kirby-Bauer method was used to determine the drug sensitivity of the bacterium in abscess secretions and blood. Several colonies were picked and prepared into bacterial suspensions of 0.5 McFarland standard, and then the suspensions were spread on Mueller-Hinton agar plates. The sensitive strips of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMZ), meropenem, and minocycline from Thermo Fisher Scientific were placed on the plates. The plates were inverted after 15 min and incubated at 35oC for 18 h. The diameters of the bacteriostatic zones were measured. The above procedures were in line with the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) operating standards. The results of four drug sensitivity tests of abscess secretions and blood cultures are shown in Table 1.

| Diameter of inhibition zone (mm) | Abscess secretion culture (first) | Abscess secretion culture (second) | Aerobic blood culture (first) | Aerobic blood culture (second) |

| TMP-SMZ | 36 | 36 | 30 | 26 |

| Meropenem | 28 | 27 | 22 | 25 |

| Minocycline | 26 | 27 | 22 | 26 |

The final diagnosis of the presented case was multiple skin abscesses associated with bacteremia due to B. gladioli.

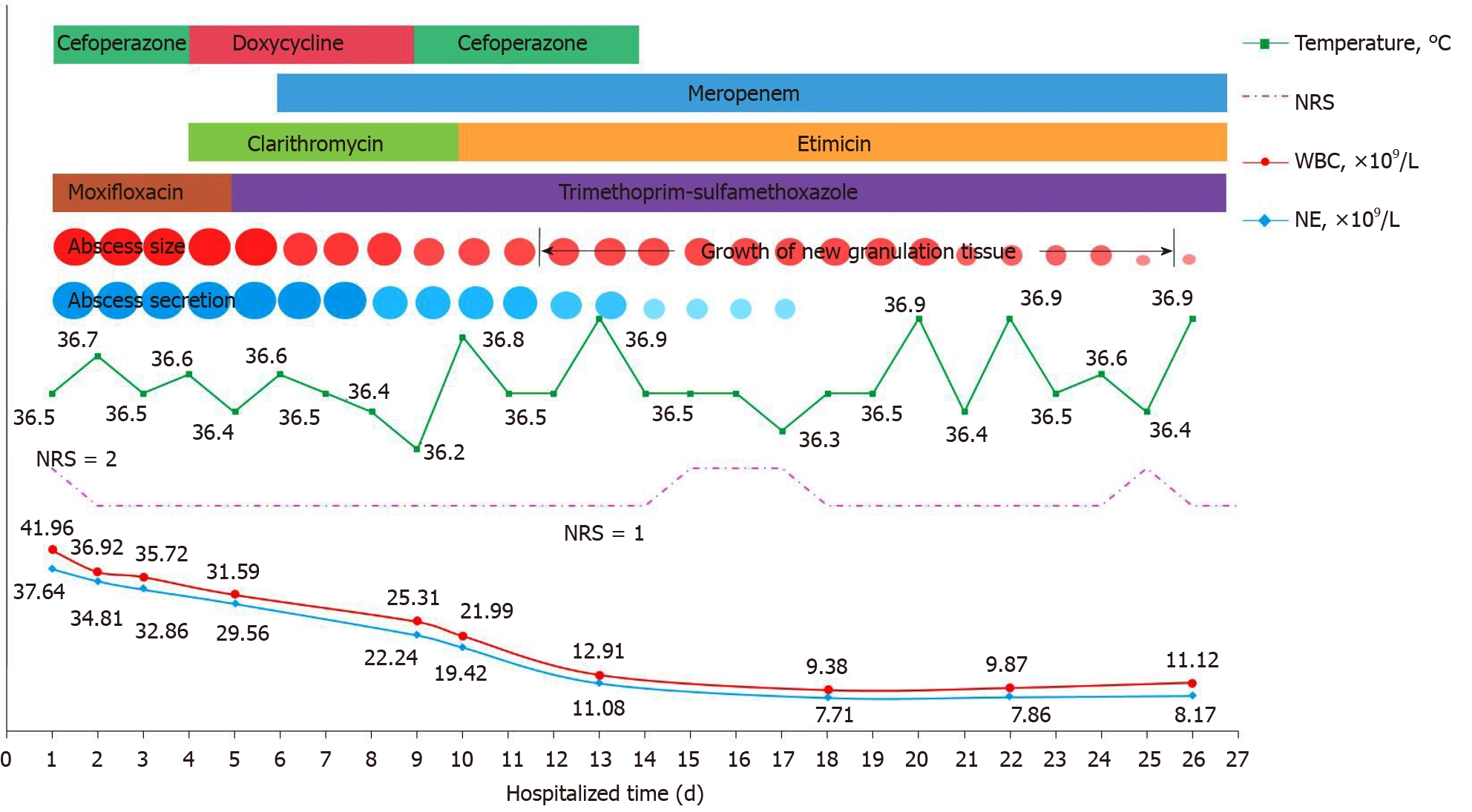

The patient underwent 27 d of treatment, and the medications administered during hospitalization are shown in Figure 2.

The patient’s multiple deep ulcers became shallower and a large amount of new granulation tissue was observed on admission day 12. On admission day 18, his skin abscesses were significantly reduced, and there were no secretions after extrusions. Auxiliary examinations showed that the absolute values of WBC and NE were normal. The changes in various indicators during hospitalization of this patient are shown in Figure 2. Most of the skin abscesses were flat on admission day 27 and the patient was discharged. He was instructed to pay attention to wound care and hygiene after discharge. He was asked to take 0.5 g meropenem intravenously 3 times/d, 0.3 g etimicin intravenously once/d, and TMP-SMZ orally twice/d (two tablets each time).

In previous studies, all patients with abscesses caused by B. gladioli infections were local[2-12], but multiple skin abscesses associated with bacteremia caused by B. gladioli were reported for the first time. Basic information of published cases and this case is shown in Table 2. B. gladioli is easily neutralized by human serum or complement factors; thus, healthy people are rarely infected with this bacterium[13,14]. This patient had a history of pneumonia, which provided the same pathological background as in the reported cases of B. gladioli infections, most of which were patients with cystic fibrosis and chronic granuloma diseases, suggesting that people with underlying diseases are more susceptible to B. gladioli. In addition, B. gladioli can also easily infect newborns with low immune functions[15]. Consistent with some reports[3,6,8], B. gladioli was obtained from the blood and abscess secretions of the patients. It has also been reported that B. gladioli was detected in lymph nodes[13], cornea[14], and sputum[16]; therefore, it is possible to improve the detection rates of the bacterium by simultaneously examining the blood, sputum, as well as various other secretions in patients. The patient in this report had no other clinical manifestations except for skin abscesses during hospitalization, which was different from previous cases who had a fever, cough, and other symptoms[8]. Previous studies showed that commercial tests such as the API[7] or VITEK[13] bacterial identification system could mistakenly identify B. gladioli as B. cepacia. Other studies used cell fatty acid analysis[2] or partial gene sequencing of 16S-23S rRNA[16] to identify B. gladioli, but the risks of misidentification always exist. In the clinical laboratory, it is important to timely and accurately identify the bacterium, which is closely related to clinical diagnosis and treatment, and carelessness may delay the diagnosis of diseases. In our laboratory, an automatic microbial identification system, MALDI-TOF MS, and full-length 16S rDNA sequencing were used to jointly identify the bacterium, which overcame the difficulties in the identification process and ensured the accuracy of the identification results.

| Ref. | Age/gender | Basic diseases | Clinical features | Medical therapy | Outcome |

| Ross et al[2], 1995 | 34 yr/M | CGD | Facial abscess and left otitis externa abscess | TMP-SMZ and amoxicillin/clavulanate | Recovery |

| Hoare et al[3], 1996 | 5 yr/M | CGD | Necrotic abscess, bacteremia and multiple hemorrhages | TMP-SMZ, ciprofloxacin and gentamicin | Recovery |

| Boyanton et al[4], 2005 | 6 yr/M | CGD | Left fourth metatarsal bone abscess | Ciprofloxacin, intravenous ticarcillin/clavulanate and gentamicin | Recovery |

| Marom et al[5], 2018 | 13 mo/not given | CGD | Facial abscess | Cefazolin, clindamycin and cephalexin | Recovery |

| Khan et al[6], 1996 | 22 yr/M | CF | Chest wall abscess, empyema and bacteremia | Imipenem | Death |

| Jones et al[7], 2001 | 17 yr/M | CF | Recurrent abscess | Piperacillin, tazocin, TMP-SMZ, meropenem, imipenem, tobramycin and ceftazidime | Death |

| Brizendine et al[8], 2012 | 39 yr/M | CF | Lung abscess, bacteremia, necrotizing pneumonia and empyema | TMP-SMZ, piperacillin/tazobactam | Death |

| Church et al[9], 2009 | 41 yr/M | CF | Mediastinal abscess | TMP-SMZ, meropenem, and ceftazidime | Recovery |

| Kennedy et al[10], 2007 | Not given | CF | Mediastinal abscess | Not given | Recovery |

| Waseem et al[11], 2008 | 17 yr/M | Type 1 diabetes | Right-sided waist abscess and diabetic ketoacidosis | Levofloxacin | Recovery |

| Choi et al[12], 2014 | 55 yr/F | No | Cystic neck abscess and silicone granulomas | Not given | Recovery |

| Present report: Wang YT, et al | 74 yr/M | Pneumonia | Multiple skin abscesses and bacteremia | Cefoperazone, clarithromycin, doxycycline, meropenem, moxifloxacin, TMP-SMZ, and etilmicin | Recovery |

Drug sensitivity tests were carried out using the Kirby-Bauer method in our laboratory. However, it was difficult for the microbiology laboratory to issue the drug sensitivity reports as the CLSI did not provide the B. gladioli drug sensitivity standards. In previous reports, the microtiter dilution method[6] and the E-test method[14] were used to test the drug sensitivity of B. gladioli. The results showed that B. gladioli was sensitive to TMP-SMZ or meropenem. In some hospitals, patients with B. gladioli infections were treated with the above two drugs, and the prognoses were good[2,3]. After treatment with TMP-SMZ and meropenem, combined with other antibacterial agents, the abscesses in our patient were reduced and finally disappeared, and the condition was well controlled. The patient has now recovered and was discharged from hospital. However, due to the differences between in vitro and in vivo environments, as well as the differences between drug sensitivity tests in vitro and drug efficacies in vivo, there will be antimicrobial drug failures and ineffective treatments. As reported by Quon et al[17], patients infected with B. gladioli can still deteriorate and die, even after treatment with TMP-SMZ and meropenem. It has also been reported that levofloxacin[11], cefazolin and gentamicin[18] were effective in the treatment of patients with B. gladioli infections. The above studies suggested that the treatment of B. gladioli was not limited to certain drugs, and multiple factors should be considered in patients with different clinical symptoms. Nevertheless, at least five people have died due to B. gladioli infections[6,8,16,17,19].

Following a literature review, it was found that the symptoms, identification methods, drug treatments, and outcomes of patients with B. gladioli infections were not the same. The reasons for these differences can be summarized as follows: (1) There were differences in defenses, immune functions, and autologous flora among different populations; (2) There were also differences in the routes and quantity of bacterial invasions; (3) There were differences in the instruments and reagents for the detection and identification of bacteria; and (4) There were differences in the judgment criteria of drug sensitivity used in different laboratories.

This paper reports the first case of multiple skin abscesses associated with bacteremia caused by B. gladioli, including the clinical features, laboratory examinations, medications, and outcome. All patients with abscesses caused by B. gladioli infections were analyzed retrospectively. The sensitivity and accuracy of B. gladioli identification results were improved by the combined applications of three identification methods, including an automatic microbial identification system, MALDI-TOF MS, and full-length 16S rDNA sequencing. Our study provides important reference values for the clinical diagnosis and treatment of B. gladioli infections, and is beneficial for the rehabilitation of patients.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medical laboratory technology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Kung WM, Meng M S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: Webster JR P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Christenson JC, Welch DF, Mukwaya G, Muszynski MJ, Weaver RE, Brenner DJ. Recovery of Pseudomonas gladioli from respiratory tract specimens of patients with cystic fibrosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:270-273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ross JP, Holland SM, Gill VJ, DeCarlo ES, Gallin JI. Severe Burkholderia (Pseudomonas) gladioli infection in chronic granulomatous disease: report of two successfully treated cases. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21:1291-1293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hoare S, Cant AJ. Chronic granulomatous disease presenting as severe sepsis due to Burkholderia gladioli. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;23:411. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Boyanton BL Jr, Noroski LM, Reddy H, Dishop MK, Hicks MJ, Versalovic J, Moylett EH. Burkholderia gladioli osteomyelitis in association with chronic granulomatous disease: case report and review. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005;24:837-839. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Marom A, Miron D, Wolach B, Gavrieli R, Rottem M. Burkholderia gladioli-associated facial pustulosis as a first sign of chronic granulomatous disease in a child - Case report and review. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2018;29:451-453. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Khan SU, Gordon SM, Stillwell PC, Kirby TJ, Arroliga AC. Empyema and bloodstream infection caused by Burkholderia gladioli in a patient with cystic fibrosis after lung transplantation. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1996;15:637-639. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Jones AM, Stanbridge TN, Isalska BJ, Dodd ME, Webb AK. Burkholderia gladioli: recurrent abscesses in a patient with cystic fibrosis. J Infect. 2001;42:69-71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Brizendine KD, Baddley JW, Pappas PG, Leon KJ, Rodriguez JM. Fatal Burkholderia gladioli infection misidentified as Empedobacter brevis in a lung transplant recipient with cystic fibrosis. Transpl Infect Dis. 2012;14:E13-E18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Church AC, Sivasothy P, Parmer J, Foweraker J. Mediastinal abscess after lung transplantation secondary to Burkholderia gladioli infection. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2009;28:511-514. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kennedy MP, Coakley RD, Donaldson SH, Aris RM, Hohneker K, Wedd JP, Knowles MR, Gilligan PH, Yankaskas JR. Burkholderia gladioli: five year experience in a cystic fibrosis and lung transplantation center. J Cyst Fibros. 2007;6:267-273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Waseem M, Al-Sherbeeni S, Al-Malki MH, Al-Ghamdi MS. Burkholderia gladioli associated abscess in a type 1 diabetic patient. Saudi Med J. 2008;29:1048-1050. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Choi HJ. Pseudocyst of the neck after facial augmentation with liquid silicone injection. J Craniofac Surg. 2014;25:e474-e475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Graves M, Robin T, Chipman AM, Wong J, Khashe S, Janda JM. Four additional cases of Burkholderia gladioli infection with microbiological correlates and review. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25:838-842. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lestin F, Kraak R, Podbielski A. Two cases of keratitis and corneal ulcers caused by Burkholderia gladioli. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:2445-2449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Zhou F, Ning H, Chen F, Wu W, Chen A, Zhang J. Burkholderia gladioli infection isolated from the blood cultures of newborns in the neonatal intensive care unit. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2015;34:1533-1537. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Wilsher ML, Kolbe J, Morris AJ, Welch DF. Nosocomial acquisition of Burkholderia gladioli in patients with cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;155:1436-1440. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Quon BS, Reid JD, Wong P, Wilcox PG, Javer A, Wilson JM, Levy RD. Burkholderia gladioli - a predictor of poor outcome in cystic fibrosis patients who receive lung transplants? Can Respir J. 2011;18:e64-e65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Tong Y, Dou L, Wang C. Peritonitis due to Burkholderia gladioli. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2013;77:174-175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Dursun A, Zenciroglu A, Karagol BS, Hakan N, Okumus N, Gol N, Tanir G. Burkholderia gladioli sepsis in newborns. Eur J Pediatr. 2012;171:1503-1509. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |