Published online Mar 6, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i7.2127

Peer-review started: July 20, 2021

First decision: October 16, 2021

Revised: October 16, 2021

Accepted: January 19, 2022

Article in press: January 19, 2022

Published online: March 6, 2022

Processing time: 224 Days and 12.7 Hours

Patients with hematological diseases are immunosuppressed due to various factors, including the disease itself and treatments, such as chemotherapy and immunotherapy, and are susceptible to infection. Infections in these patients often progress rapidly to sepsis, which is life-threatening.

To evaluate the diagnostic efficacy of the neutrophil CD64 (nCD64) index, compared to procalcitonin (PCT) and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), for the identification of early sepsis in patients with hematological diseases.

This was a prospective analysis of patients with hematological diseases treated at the Fuxing Hospital affiliated with Capital Medical University, between March 2014 and December 2018. The nCD64 index was quantified by flow cytometry and the Leuko64 assay software. The factors which may affect the nCD64 index levels were compared between patients with different infection statuses (local infection, sepsis, and no infection), and the control group and the nCD64 index levels were compared among the groups. The diagnostic efficacy of the nCD64 index, PCT, and hs-CRP for early sepsis was evaluated among patients with hematological diseases.

A total of 207 patients with hematological diseases (non-infected group, n = 50; locally infected group, n = 67; sepsis group, n = 90) and 26 healthy volunteers were analyzed. According to the absolute neutrophil count (ANC), patients with hematological diseases without infection were divided into the normal ANC, ANC reduced, and ANC deficiency groups. There was no statistically significant difference in the nCD64 index between these three groups (P = 0.586). However, there was a difference in the nCD64 index among the non-infected (0.74 ± 0.26), locally infected (1.47 ± 1.10), and sepsis (2.62 ± 1.60) groups (P < 0.001). The area under the diagnosis curve of the nCD64 index, evaluated as the difference between the sepsis and locally infected group, 0.777, which was higher than for PCT (0.735) and hs-CRP (0.670). The positive and negative likelihood ratios were also better for the nCD64 index than either PCT and hs-CRP.

Our results indicate the usefulness of the nCD64 index as an inflammatory marker of early sepsis in hematological patients.

Core Tip: Early sepsis in hematological patients is difficult to diagnosis, often progresses rapidly, and has a high mortality rate. The neutrophil CD64 (nCD64) index has high sensitivity and specificity as a diagnostic marker of early sepsis. We confirm the usefulness of this index in hematological patients, with the diagnostic efficacy of the nCD64 index for early sepsis in this clinical population being significantly better than high-sensitivity C-reactive protein and superior to procalcitonin. The index can be helpful in evaluating the severity of infection in patients with hematological diseases.

- Citation: Shang YX, Zheng Z, Wang M, Guo HX, Chen YJ, Wu Y, Li X, Li Q, Cui JY, Ren XX, Wang LR. Diagnostic performance of Neutrophil CD64 index, procalcitonin, and C-reactive protein for early sepsis in hematological patients. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(7): 2127-2137

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i7/2127.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i7.2127

Our findings indicate that the neutrophil CD64 (nCD64) index is a valuable biomarker for early sepsis in hematological patients and is helpful in distinguishing sepsis from local infection, with the diagnostic efficacy of the nCD64 index being superior to that of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) and procalcitonin (PCT). The nCD64 index test may be an additional tool that could be routinely used for the identification of early sepsis in febrile hematological patients.

Sepsis often progresses rapidly in critically ill patients and is associated with a high mortality rate[1]. Patients with hematological diseases are in an immunosuppressive state and, therefore, are more susceptible to sepsis. These patients often show no obvious clinical symptoms and signs in the early stage of sepsis, making diagnosis and determination of the severity of infection difficult. Sepsis is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in hematological patients[2-5]. Owing to the serious time lag for bacterial culture results, the quick detection of inflammatory markers provides an advantage in terms of time. nCD64 has been described as an accurate biomarker for the diagnosis of sepsis in critical patients and newborns[6] and can help determine the severity of infection[7-9]. However, there are few studies on the nCD64 index in the field of hematological diseases. At present, there are only reports on the nCD64 index for bacterial infections in patients with hematological diseases[10,11], with no report on its use for early diagnosis of sepsis in hematological patients.

There has been no large-scale clinical trial to confirm whether the expression of mature nCD64 in peripheral blood of hematological patients without infection is up-regulated. A literature review by Westwood et al[12] confirmed that the percentage of CD64 positive cells in mature bone marrow cells of patients with myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome was not statistically different from that of a normal control group[12]. In another literature review, Ohsaka et al[13] reported that the percentage of nCD64 positive cells in patients with multiple myeloma and polycythemia vera was higher than for a normal control group, suggesting that this elevation reflected the activation of neutrophils involved in the anti-tumor process of the body's immune system[13]. However, the number of cases in the experimental groups of these two literature reviews was 18 and 19, respectively, both of which were relatively small. Moreover, data on the CD64 mean fluorescent intensity and the CD64 index were not included. The results of our study showed that the nCD64 index in peripheral blood of hematological patients without infections was not statistically different from that of the normal control group. As such, the nCD64 index could be used for the early diagnosis of sepsis in hematological patients. In addition, the detection of peripheral blood nCD64 index was not affected by the peripheral blood neutrophil count, with no significant difference in the index between the three ANC groups (normal, reduced, and deficient ANC groups). This conclusion is consistent with the results reported by Xiong et al[11], suggesting that agranulocytosis did not affect the detection of nCD64 index.

Glucocorticoid drugs are widely used in hematology. When sepsis occurs, pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as colony stimulating factors, are released and neutrophils are activated, resulting in high expression of CD64 molecules. We evaluated the effect of glucocorticoids on the nCD64 index by comparing the index between patients in the no-infection group who had been treated with glucocorticoids within the week prior to the blood sample compared to those without glucocorticoids treatment. We found no significant difference in the nCD64 index between these two groups. This finding agrees with the results by Allen et al[14] who found no difference in the nCD64 index in patients with autoimmune diseases treated with and without glucocorticoids.

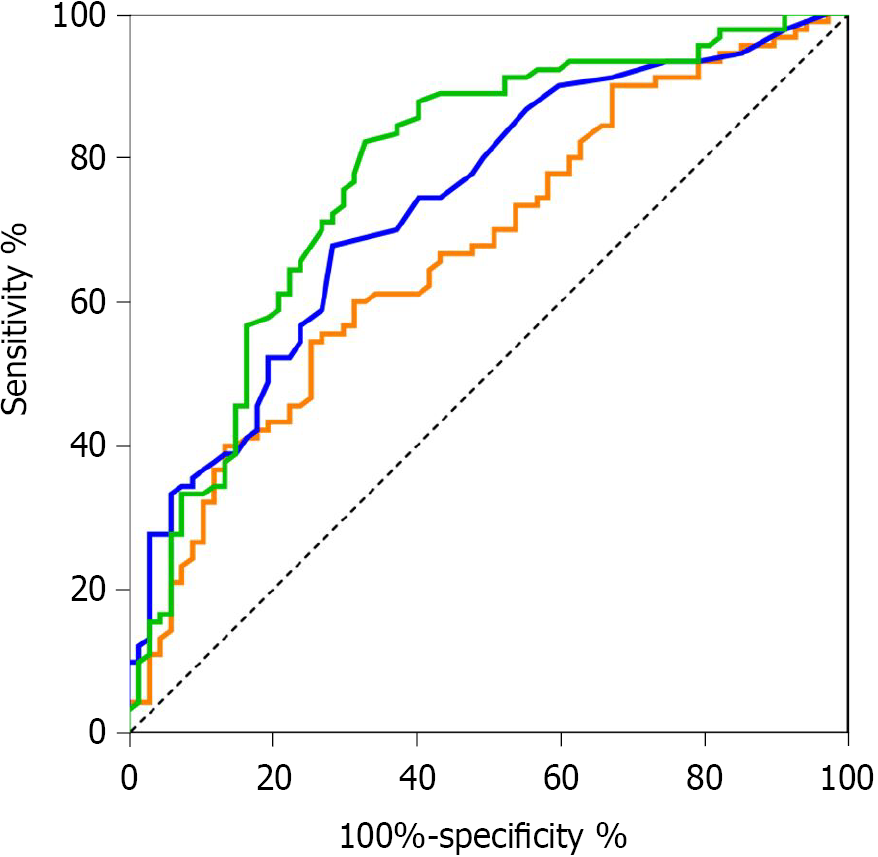

We evaluated the diagnostic value of the nCD64 index for the early stage of sepsis in hematological patients against the use of PCT or hs-CRP. The area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was greater for the nCD64 index than for PCT (0.777 vs 0.735) or CRP (0.777 vs 0.670). Based on our findings, both the nCD64 index and PCT have a moderate diagnostic value for early sepsis in hematological patients, which is significantly better than that of hs-CRP. This is the same conclusion as reported by Yeh et al[6] in their meta-analysis. As the area under the curve (AUC) of the nCD64 index is slightly higher than that for PCT, the nCD64 index may be better than PCT in the diagnosis of early sepsis in hematological patients; however, it will be necessary to further expand the sample size to prove that the nCD64 index is superior to PCT. The Youden index of the nCD64 index was also higher at 0.494 than for PCT (0.394) or hs-CRP (0.29). The positive and negative likelihood ratios of the nCD64 index were also better for the nCD64 index than PCT, which further suggests that the nCD64 index might perform better than PCT for diagnosing early sepsis in hematological patients. In a study comparing the diagnostic value of the nCD64 index and PCT for patients with leukemia and a bacterial infection, Kongman et al[15] concluded that the specificity and sensitivity (0.71 and 0.90, respectively) of the nCD64 index for diagnosis of bacterial infection were slightly higher than those for PCT (0.67 and 0.89, respectively). This conclusion, together with the findings of our study, indicates a trend toward a diagnostic superiority of the nCD64 index over PCT for early sepsis in hematological patients. However, both the study by Kongman et al[15] and our study are limited by the relatively small study samples, with lack of statistical confirmation of a difference in the AUC of the ROC.

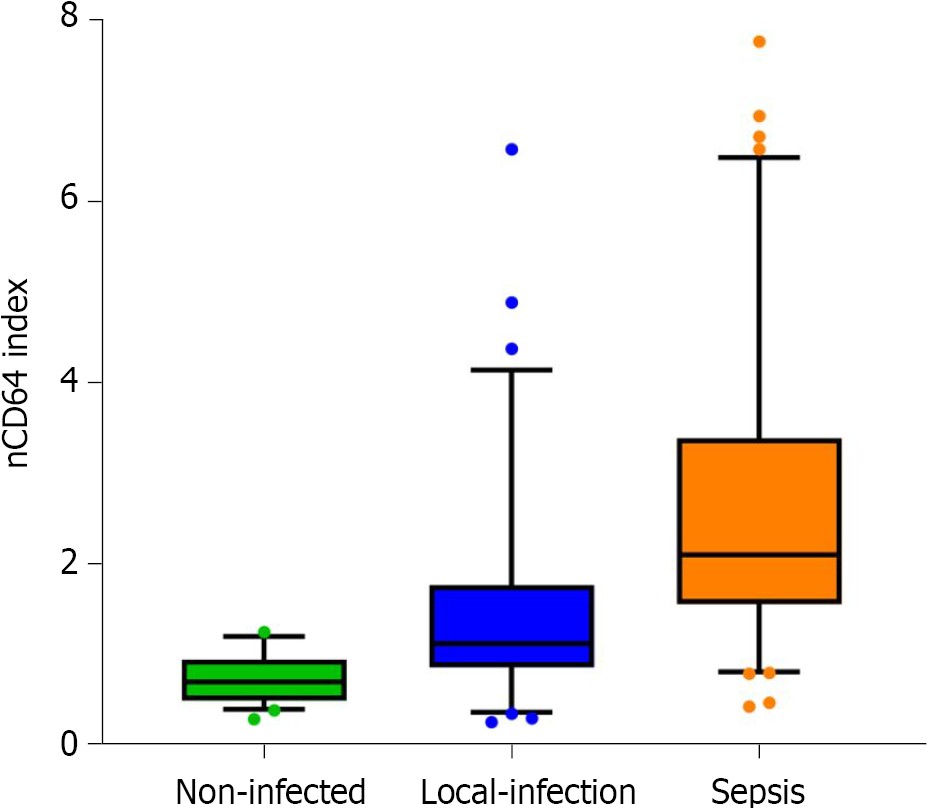

In order to further explore the application of the nCD64 index for the assessment of the severity of infection in hematological patients, we compared the nCD64 index among patients with no infection, patients with local infection, and patients with sepsis. We found the nCD64 index to be higher in patients with a local infection compared to those without an infection (P < 0.001), as well as being higher in the sepsis compared to the local infection group (P < 0.001). These results indicate the feasibility of using the nCD64 index to assess the severity of infection in hematological patients. However, due to the fact that there are few patients in the sepsis group, we were unable to further evaluate the utility of the nCD64 index to differentiate severe sepsis and septic shock. In the field of hematology, the utility of the nCD64 to assess the severity of infection has not been previously addressed. In their study on the diagnosis of sepsis in critically ill patients, Ghosh et al[16] showed that the level of nCD64 expression is related to the severity of infection. Furthermore, our finding that the nCD64 index can be used to diagnose local infections in hematological patients is consistent with the findings of Wan et al[10] and Wu et al[17].

At present, there is no unified conclusion, locally or internationally, regarding the expression of nCD64 in the identification of infectious pathogens. Some studies have suggested that the expression of nCD64 in patients with bacterial infection is significantly increased[18]. Another study also reported CD64 to be highly expressed on neutrophils in viral infections[19]. However, due to the specificity of hematological diseases and treatments received, the patients in our study sample were susceptible to multiple infections during hospitalization, which could account for the bacterial, viral, and fungal infections in our study group.

This study had some limitations, mainly its small sample size and use of data from a single center. Although we report a high diagnostic sensitivity and specificity of the nCD64 index, further multicenter studies with larger sample sizes are needed to confirm the diagnostic superiority of the nCD64 index over PCT and hs-CRP. Furthermore, the potential use of the nCD64 index to evaluate the severity of infection in hematological patients warrants further investigation.

A total of 207 patients with hematological diseases were included, with men comprising 57.0% (118/207) of the sample; the median age of our study sample was 60 (range, 14-88) years. The 26 healthy volunteer group included 13 men, with a median age of 46 (range, 22-76) years. The distribution of sex, age, and white blood cell, absolute neutrophil (ANC), red blood cell (RBC), and platelet (PLT) counts are reported for each patient group and the control group in Table 1. While there was no significant difference in the distribution of age and sex among the groups, the ANC was lower in the sepsis group. The site of infection and the number of positive cases of bacterial culture for each patient group (no infection, local infection, and sepsis) are summarized in Table 2. Pulmonary infections were the most common, with an infection rate of 53.5%. Fungal infections were identified in 43 patients (27.39%). Positive blood cultures were identified in 11 infected patients (7%) and included 2 cases of Klebsiella pneumoniae, 2 cases of Escherichia coli, 3 cases of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, 2 cases of Staphylococcus epidermidis, 1 case of Enterobacter cloacae subspecies, and 1 case of Listeria monocytogenes.

| Diagnosis | Patients with hematological diseases (n = 207) | Normal controls (n = 26) | P value | ||

| Local infection | Sepsis | No infection | |||

| Sex, n (%) | 0.255 | ||||

| Female | 34 (50.7) | 58 (64.4) | 26 (52.0) | 13 (50.0) | |

| Male | 33 (49.3) | 32 (35.6) | 24 (48.0) | 13 (50.0) | |

| Age, median [range], yr | 60 [14-86] | 60 [18-84] | 60 [21-88] | 46 [22-76] | 0.726 |

| WBC, median [range] (× 109/L) | 3.7 [0.30-136.0] | 2.55 [0.30-161.0] | 3.4 [0.70-20.4] | 0.090 | |

| ANC, median [range] (× 109/L) | 2.31 [0.00-45.80] | 0.745 [0.00-39.00] | 2.1 [0.10-13.59] | 0.013 | |

| RBC, median [range] (× 1012/L) | 2.53 [1.15-4.87] | 2.40 [1.13-4.51] | 3.05 [1.68-4.62] | < 0.001 | |

| PLT, median [range] (× 109/L) | 56 [6-456] | 34 [1-462] | 133 [8-517] | < 0.001 | |

| Infection sites | Hematological patients with local infection (n = 67) | Hematological patients with sepsis (n = 90) | ||||

| Clinical diagnosis (n = 55) | Positive culture of secretions (n = 11) | Positive blood culture (n = 1) | Clinical diagnosis (n = 54) | Positive culture of secretions (n = 26) | Positive blood culture (n = 10) | |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 20 | 1 | - | 123 | 54 | 1 |

| Lung infection | 271 | 6 | 1 | 315 | 146 | 5 |

| Suppurative tonsillitis | - | - | - | 1 | 2 | - |

| Oral infections | 2 | 2 | - | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Cholecystitis | - | - | - | 2 | - | - |

| Appendicitis | 2 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Perianal infection | - | - | - | 27 | - | - |

| Skin and soft tissue infection | 22 | 1 | - | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Urinary tract infection | - | 1 | - | 48 | 2 | - |

| Unknown infection site | 2 | - | - | - | - | 1 |

The laboratory reference value of the nCD64 index was based on the values calculated from the peripheral blood sample of the 26 normal controls: 0.71 ± 0.31 (95%CI, 0.59-0.84). The average nCD64 index for the 50 non-infected hematological patients was 0.74 ± 0.26 (95%CI, 0.66-0.81), which was similar to the index for the control group (P = 0.734).

The non-infected hematological patient group was subdivided based on the ANC count as follows: Normal ANC group (ANC absolute count ≥ 2.0 × 109 / L), ANC reduced group (ANC absolute count 0.5 × 109 / L-2.0 × 109 / L), and ANC deficient group (ANC absolute count < 0.5 × 109 / L). The average nCD64 index for the 29 patients in the normal ANC group was 0.71 ± 0.21, compared to 0.81 ± 0.31 for the 12 patients in the ANC reduced group and 0.72 ± 0.34 for the 9 patients in the ANC deficient group, with no significant differences between the groups (P = 0.586).

The non-infected hematological patient group was subdivided according to whether glucocorticoids were used within one week before blood collection. The average nCD64 index for the 41 patients without glucocorticoid use was 0.76 ± 0.27, compared to 0.63 ± 0.17 for the 9 patients in whom glucocorticoids were used; however, this difference was not significant (P = 0.17).

The area under the ROC curve (AUC, Figure 1) for the nCD64 index differentiating the sepsis and local infection groups was 77.7%, which was slightly higher than for PCT (73.5%) and significantly higher than for hs-CRP (67.0%). The diagnostic efficacy of the nCD64 index and PCT was at a medium level, with low diagnostic efficacy for hs-CRP (Figure 2). The Youden index for the nCD64 index was 0.60, compared to 0.41 for PCT and 0.36 for hs-CRP. The best cutoff value, sensitivity, specificity, and likelihood ratio of the three markers (nCD64 index, PCT, and hs-CRP) are reported in Table 3. The positive and negative likelihood ratios of the nCD64 index were better than those for PCT and hs-CRP.

| Indicator | AUC | Best cutoff | Sensitivity | Specificity | Likelihood ratio | |

| Positive | Negative | |||||

| nCD64 index | 77.7% | 1.465 | 82.3% | 67.2% | 2.51 | 0.26 |

| PCT (ng/mL) | 73.5% | 0.175 | 67.8% | 71.6% | 2.39 | 0.45 |

| hs-CRP (mg/L) | 67.0% | 69.8 | 54.4% | 74.6% | 2.18 | 0.60 |

The average nCD64 index for the hematological patient groups was as follows: 0.74 ± 0.26 (95%CI 0.66-0.81) for the no-infection group, 1.47 ± 1.10 (95%CI 1.20-1.74) for the local infection group, and 2.62 ± 1.60 (95%CI 2.28-2.96) for the sepsis group. The index was higher for the local infection than the no-infection group (P < 0.001), and for the sepsis group compared to the local infection group (P < 0.001; Figure 3).

This study was approved by the Fuxing Hospital, Capital Medical University IRB (2014FXHEC-KY020). The Ethics Committee waived the need for informed consent due to the use of anonymized data for analysis.

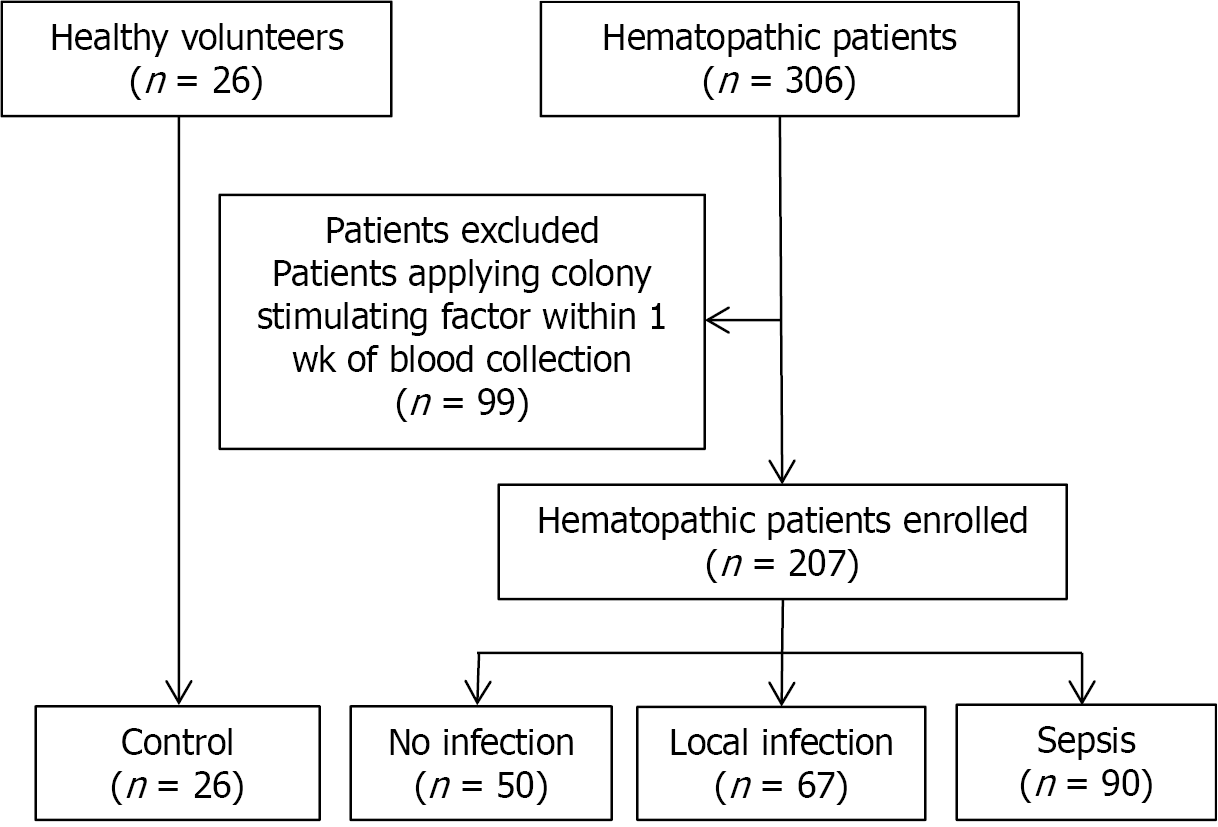

Patients with hematological diseases who presented for assessment and treatment at Fu-Xing Hospital, affiliated with Capital Medical University, between March 2014 and December 2018 were prospectively enrolled. A total of 207 hematological patients were included, with the following distribution of diseases: acute myeloid leukemia, n = 96; acute lymphocytic leukemia, n = 22; myelodysplastic syndrome, n = 34; myeloproliferative diseases, n = 12; chronic lymphocytic leukemia, n = 7; non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, n = 14; multiple myeloma, n = 15; primary systemic amyloidosis, n = 1; aplastic anemia, n = 5; and idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, n = 1. Excluded were hematological patients receiving colony stimulating factors within one week of blood sampling (n = 99).

The following clinical variables were collected within the first 24 h of suspected infection: sex; age; symptoms and signs; body temperature; white blood cell, RBC, absolute neutrophil, and PLT counts; and the nCD64 index. The Sequential (Sepsis-Related) Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score, serum lactate levels, and treatments provided were also collected. For comparison, blood samples from 26 healthy adults were also collected.

We used the Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3, 2016) criteria, which define sepsis as a life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulation in the host immune response to an infection[1]. The diagnosis of sepsis was based on evident signs of bacterial infection and a SOFA score ≥ 2. Using these criteria, hematological patients were classified into the following groups for analysis, as shown in Figure 2: non-infected group (n = 50), local infection group (n = 67), and sepsis group (n = 90).

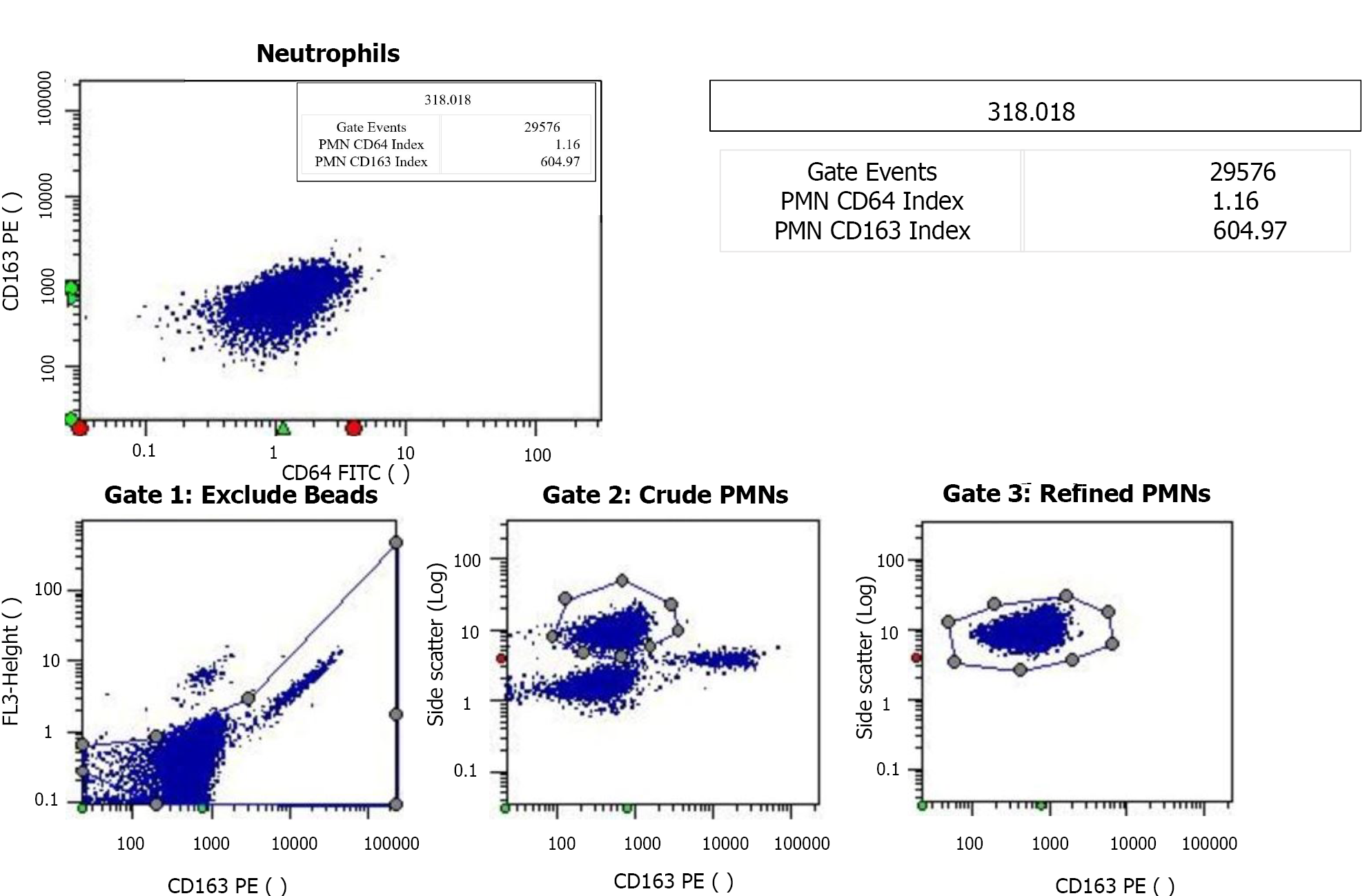

The CD64 index was quantified using the CantoII flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, and Company; Franklin Lakes, NJ, United States). Specifically, 50 μL of EDTA anticoagulated whole blood was collected from each patient and labeled with monoclonal antibodies at room temperature. Leuko64 reagent, including CD64FITC + CD163PE antibodies (Trillium Diagnostics, LLC, Brewer, ME, United States), was added to the sample. The sample was then mixed thoroughly and incubated at 25ºC in the dark for 15 min. Erythrocyte lysin was then added, followed by the addition of 5 μL of Leuko64 beads. Once the sample was clear and translucent, the mature nCD64 index was measured using Data-Interpolating Variational Analysis software (Becton, Dickinson, and Company; Franklin Lakes, NJ, United States) and the gating strategy for mature neutrophils was side scatter and CD163 (Figure 4). Standard fluorescent microspheres were used to calibrate the instrument prior to obtaining measurements. The CD64 index was calculated as follows: Average nCD64 fluorescence intensity /average fluorescence microsphere fluorescence intensity) × 2.14.

Analyses were performed using Epidata statistical software (version 3.1; The Epidata Association, Odense, Denmark), SPSS (version 16.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States), and GraphPad statistical software (2018; GraphPad Software, Inc, San Diego, CA, United States). The normality of distribution of measured data was evaluated using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov normality test. Normally distributed data (nCD64 index, PCT, and hs-CRP) were described by their mean ± SD. Independent sample or adjusted t-tests were used, as appropriate, for between-group comparisons of these variables, with q or rank sum tests used for comparison among all three groups (no infection, local infection, and sepsis groups). Non-normally distributed data (age and the white blood cell counts, neutrophil, RBC, and PLT counts, were described as medians (ranges). ROC curve analysis was used to compare the diagnostic efficacy of the nCD64 index to the PCT and hs-CRP for early-stage sepsis. The AUC, Youden index, sensitivity, specificity, positive likelihood ratio, and negative likelihood ratio were calculated for the “best cutoff” value. All tests were deemed statistically significant with a two-sided P value < 0.05.

Sepsis is a systemic, deleterious host response to infection which progresses rapidly, leading to severe sepsis and septic shock, with a high rate of mortality[1]. Patients with hematological diseases are susceptible to infection due to their immunosuppressed status which results from the disease itself and treatments, such as chemotherapy and immunotherapy, among other factors. Infections in this clinical population often progress rapidly to sepsis, which seriously threatens the patient's life[2,3]. The speed and appropriateness of therapy administered in the initial hours after the development of severe sepsis are likely to influence the outcome[1]. Early identification of sepsis, however, is difficult owing to the lack of specific clinical manifestations, especially in patients with hematological diseases. Inflammatory biomarkers could provide an advantage in this regard; however, the optimal inflammatory markers to use for early diagnosis of sepsis have not yet been identified.

The CD64 molecule is an immunoglobulin IgG Fc fragment receptor I belonging to the immunoglobulin superfamily[20]. Infections or invasions of endotoxins activate neutrophils, increasing the expression of CD64 molecules. This increased expression of nCD64 can be detected within 4-6 h of onset of an infection. As such, nCD64 is a marker of early inflammation[21]. Recent studies in the field of pediatrics and intensive care medicine have shown that the detection of CD64 on the surface of neutrophils is helpful in the early diagnosis and assessment of the severity of sepsis, with its diagnostic efficacy for early stage of sepsis being superior to other classic biological inflammatory markers, such as PCT, CRP, and interleukin-6[6-8]. The elevation in nCD64 level is closely related to the degree of organ failure and mortality in patients with sepsis[7]. At present, there has been no research regarding the application of the nCD64 index for the diagnosis of early sepsis in hematological patients. As better biological markers are needed to diagnose sepsis and assess the severity of infection in hematological patients, our aim in this study was to explore the use of the nCD64 index for the early diagnosis of sepsis in this clinical population and to evaluate its diagnostic efficacy compared to PCT and hs-CRP.

This study confirmed that the neutrophil CD64 (nCD64) index can be used for early diagnosis of sepsis in hematological patients. The nCD64 index test may be an additional tool that could be routinely used for the identification of early sepsis in febrile hematological patients.

Our findings indicate that the nCD64 index is a valuable biomarker for early sepsis in hematological patients and is helpful in distinguishing sepsis from local infection, with the diagnostic efficacy of the nCD64 index being superior to that of high-sensitive C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) and procalcitonin (PCT).

The nCD64 index as a function of the infection status was as follows: Non-infected group, 0.74 ± 0.26; local infection group, 1.47 ± 1.10; and the sepsis group, 2.62 ± 1.60 (P < 0.001 between each group). The area under the diagnostic curve for the nCD64 index (difference between the sepsis and locally infected groups) was 0.777, which was higher than for the diagnostic curve using PCT (0.735) or hs-CRP (0.670). Overall, the positive and negative likelihood ratios were better for the nCD64 index than for PCT or hs-CRP.

Patients with hematological disease treated at our hospital between March 2014 and December 2018 were analyzed. The nCD64 index was tested using flow cytometry and Leuko64 assay software. The factors which may affect the nCD64 index levels, as a function of infection status, were analyzed. The diagnostic efficacy of the nCD64 index, PCT, and hs-CRP for early sepsis in patients with hematological malignancies were compared.

In this study, we evaluated the diagnostic efficacy of the nCD64 index, PCT, and hs-CRP for early diagnosis of sepsis in patients with hematological diseases.

Timely identification of early sepsis is very difficult in hematological patients due to the lack of specific clinical manifestations.

Sepsis is a systemic, deleterious, host response to infection which can lead to severe sepsis and septic shock. Sepsis progresses rapidly and is associated with a high mortality rate, especially in hematological patients.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Hematology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: BEHERA B S-Editor: Wu YXJ L-Editor: Webster JR P-Editor: Wu YXJ

| 1. | Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A, Annane D, Gerlach H, Opal SM, Sevransky JE, Sprung CL, Douglas IS, Jaeschke R, Osborn TM, Nunnally ME, Townsend SR, Reinhart K, Kleinpell RM, Angus DC, Deutschman CS, Machado FR, Rubenfeld GD, Webb SA, Beale RJ, Vincent JL, Moreno R; Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines Committee including the Pediatric Subgroup. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2012. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:580-637. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4031] [Cited by in RCA: 3979] [Article Influence: 331.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Christopeit M, Schmidt-Hieber M, Sprute R, Buchheidt D, Hentrich M, Karthaus M, Penack O, Ruhnke M, Weissinger F, Cornely OA, Maschmeyer G. Prophylaxis, diagnosis and therapy of infections in patients undergoing high-dose chemotherapy and autologous haematopoietic stem cell transplantation. 2020 update of the recommendations of the Infectious Diseases Working Party (AGIHO) of the German Society of Hematology and Medical Oncology (DGHO). Ann Hematol. 2021;100:321-336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kochanek M, Schalk E, von Bergwelt-Baildon M, Beutel G, Buchheidt D, Hentrich M, Henze L, Kiehl M, Liebregts T, von Lilienfeld-Toal M, Classen A, Mellinghoff S, Penack O, Piepel C, Böll B. Management of sepsis in neutropenic cancer patients: 2018 guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Working Party (AGIHO) and Intensive Care Working Party (iCHOP) of the German Society of Hematology and Medical Oncology (DGHO). Ann Hematol. 2019;98:1051-1069. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 16.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Torres VB, Azevedo LC, Silva UV, Caruso P, Torelly AP, Silva E, Carvalho FB, Vianna A, Souza PC, Godoy MM, Azevedo JR, Spector N, Bozza FA, Salluh JI, Soares M. Sepsis-Associated Outcomes in Critically Ill Patients with Malignancies. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12:1185-1192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Al-Zubaidi N, Shehada E, Alshabani K, ZazaDitYafawi J, Kingah P, Soubani AO. Predictors of outcome in patients with hematologic malignancies admitted to the intensive care unit. Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Ther. 2018;11:206-218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Yeh CF, Wu CC, Liu SH, Chen KF. Comparison of the accuracy of neutrophil CD64, procalcitonin, and C-reactive protein for sepsis identification: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intensive Care. 2019;9:5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Yin WP, Li JB, Zheng XF, An L, Shao H, Li CS. Effect of neutrophil CD64 for diagnosing sepsis in emergency department. World J Emerg Med. 2020;11:79-86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Song Y, Chen Y, Dong X, Jiang X. Diagnostic value of neutrophil CD64 combined with CRP for neonatal sepsis: A meta-analysis. Am J Emerg Med. 2019;37:1571-1576. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Tang Z, Qin D, Tao M, Lv K, Chen S, Zhu X, Li X, Chen T, Zhang M, Zhong M, Yang H, Xu Y, Mao S. Examining the utility of the CD64 index compared with other conventional indices for early diagnosis of neonatal infection. Sci Rep. 2018;8:9994. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Wan SG, Zheng CC, Han X, Zhao H, Sun XJ, Su L, Xia CQ. Evaluation of neutrophilic CD64 index as a diagnostic marker of bacterial infection in blood diseases. Zhongguo Shi Yan Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi. 2014;22:797-800. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Xiong SD, Pu LF, Wang HP, Hu LH, Ding YY, Li MM, Yang DD, Zhang C, Xie JX, Zhai ZM. Neutrophil CD64 Index as a superior biomarker for early diagnosis of infection in febrile patients in the hematology department. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2017;55:82-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Westwood NB, Copson ER, Page LA, Mire-Sluis AR, Brown KA, Pearson TC. Activated phenotype in neutrophils and monocytes from patients with primary proliferative polycythaemia. J Clin Pathol. 1995;48:525-530. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ohsaka A, Saionji K, Takagi S, Igari J. Increased expression of the high-affinity receptor for IgG (FcRI, CD64) on neutrophils in multiple myeloma. Hematopathol Mol Hematol. 1996;10:151-160. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Allen E, Bakke AC, Purtzer MZ, Deodhar A. Neutrophil CD64 expression: distinguishing acute inflammatory autoimmune disease from systemic infections. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61:522-525. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kong M, Zhang HM, Luo ZZ, Cao XC, Lu ZX. Value of CD64 in early diagnosis of leukemia complicated with bacterial infection. Huazhongkeji Daxue Xuebao. 2014;6:701-704. |

| 16. | Ghosh PS, Singh H, Azim A, Agarwal V, Chaturvedi S, Saran S, Mishra P, Gurjar M, Baronia AK, Poddar B, Singh RK, Mishra R. Correlation of Neutrophil CD64 with Clinical Profile and Outcome of Sepsis Patients during Intensive Care Unit Stay. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2018;22:569-574. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Wu ZD, Zhou JB, Meng WJ. Significance of CD64 in monitoring of infection after chemotherapy in patients with hematologica malignancies. J Pract Onco. 2013;28:473-475. |

| 18. | García-Salido A, de Azagra-Garde AM, García-Teresa MA, Caro-Patón GL, Iglesias-Bouzas M, Nieto-Moro M, Leoz-Gordillo I, Niño-Taravilla C, Sierra-Colomina M, Melen GJ, Ramírez-Orellana M, Serrano-González A. Accuracy of CD64 expression on neutrophils and monocytes in bacterial infection diagnosis at pediatric intensive care admission. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2019;38:1079-1085. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Nuutila J. The novel applications of the quantitative analysis of neutrophil cell surface FcgammaRI (CD64) to the diagnosis of infectious and inflammatory diseases. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2010;268-274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Takai S, Kasama M, Yamada K, Kai N, Hirayama N, Namiki H, Taniyama T. Human high-affinity Fc gamma RI (CD64) gene mapped to chromosome 1q21.2-q21.3 by fluorescence in situ hybridization. Hum Genet. 1994;93:13-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Patnaik R, Azim A, Agarwal V. Neutrophil CD64 a Diagnostic and Prognostic Marker of Sepsis in Adult Critically Ill Patients: A Brief Review. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2020;24:1242-1250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |