Published online Feb 26, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i6.2045

Peer-review started: October 8, 2021

First decision: October 27, 2021

Revised: November 9, 2021

Accepted: January 14, 2022

Article in press: January 14, 2022

Published online: February 26, 2022

Processing time: 138 Days and 7.8 Hours

After undergoing radical cystectomy combined with hysterectomy, female patients may suffer from pelvic organ prolapse due to the destruction of pelvic structures, which mainly manifests as the prolapse of tissues of the vulva to varying degrees and can be accompanied by symptoms, such as bleeding and inflammation. Once this complication is present, surgical intervention is needed to resolve it. Therefore, preventing and managing this complication is especially important.

The postoperative occurrence of acute enterocele is rare, and a case of acute small bowel vaginosis 2 mo after radical cystectomy with hysterectomy is reported. When the patient was admitted, physical examination revealed that the small bowel was displaced approximately 20 cm because of vaginocele. A team of gynecological, general surgery, and urological surgeons was employed to return the small bowel and repair the lacerated vaginal wall during the emergency operation. Eventually, the patient recovered, and no recurrence was seen in the half year of follow-up.

We review the surgical approach for such patients, analyze high-risk factors for the disease and suggest corresponding preventive measures.

Core Tip: After undergoing radical cystectomy combined with hysterectomy, female patients may suffer from pelvic organ prolapse due to the destruction of pelvic structures, which mainly manifests as the prolapse of tissues of varying degrees in the vulva and can be accompanied by symptoms, such as bleeding and inflammation. Once this complication is present, we need surgical intervention to resolve it. So how to prevent and manage this complication is especially important. We review the surgical approach for such patients, analyzes high-risk factors for the disease and focuses on suggesting corresponding preventive measures.

- Citation: Liu SH, Zhang YH, Niu HT, Tian DX, Qin F, Jiao W. Vaginal enterocele after cystectomy: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(6): 2045-2052

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i6/2045.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i6.2045

Bladder cancer is the most common malignant tumor of the urinary system. The incidence rate in males is 3-4 times that in women. Although the probability of male cancer is far greater than that of female cancer, the possibility of myometrial invasion is greater in women[1]. The preferred choice of treatment for women with muscle-invasive bladder cancer is radical cystectomy and urinary diversion. However, for patients with locally advanced disease, it may be necessary to enucleate the uterus and bilateral adnexa and even a segment of the anterior vaginal wall for bladder removal, thereby reducing the likelihood of recurrence and metastasis after surgery. Given that destruction of the original structure of the pelvic cavity combined with the loss of some tissues, such as ligaments and fascia, leads to the absence of support for the vagina and vulvar region of the patient, the probability of developing pelvic organ prolapse (POP) after surgery increases.

In patients with an orthotopic neobladder, the presence of POP can lead to compression of the neobladder, triggering urinary retention and dysuria. POP causes patients to experience a reduction in quality of life, and surgical treatment is often indicated for patients with sexual needs. However, patients with acute enterocele are at risk of bowel rupture as well as mesenteric torsion, which subsequently triggers intestinal avascular necrosis, requiring timely multidisciplinary joint surgical intervention[2]. The patient's previous surgical history can indicate whether it is likely that various levels of intra-abdominal adhesions are present. In addition, the absence of pelvic tissues (muscles, ligaments, and vaginal supporting tissues) undoubtedly increases the difficulty of surgical repair. Two surgical approaches are available: transabdominal or transvaginal approaches using vaginal atresia[3] or posterior vaginal wall repair to reduce the probability of secondary POP after surgery. It has also been reported that pelvic mesh placement results in good outcomes. To reduce patient suffering and expense, we believe that preventive measures are needed to reduce the incidence of POP after radical cystectomy in women. Importantly, doctors need to understand the anatomy of the female reproductive system, reduce the damage to important ligaments and fascia during surgery, and preserve vaginal support as much as possible[4,5]. However, more important is adequate preoperative preparation and individualized postoperative care.

The patient was a 72-year-old woman who experienced sudden spontaneous small bowel bulging into the vagina during defecation at home and was transferred to our hospital 10 h after onset for treatment.

The patient suffered from excruciating abdominal pain and had assumed and maintained a hunched posture for over 10 h.

The patient was pregnant three times, gave birth two times, and miscarried once. Her height, weight and body mass index were 158 cm, 56 kg and 22.4 kg/m2, respectively. The patient had no history of chronic disease. She underwent radical cystectomy, uterine and double adnexectomy and bilateral ureterolithotomy due to bladder malignancy two months prior. Postoperative pathology confirmed high-grade invasive urothelial carcinoma invading the deep muscularis without involvement of urethral resection margins and bilateral ureteral stumps.

The personal and family history of the patient was unremarkable.

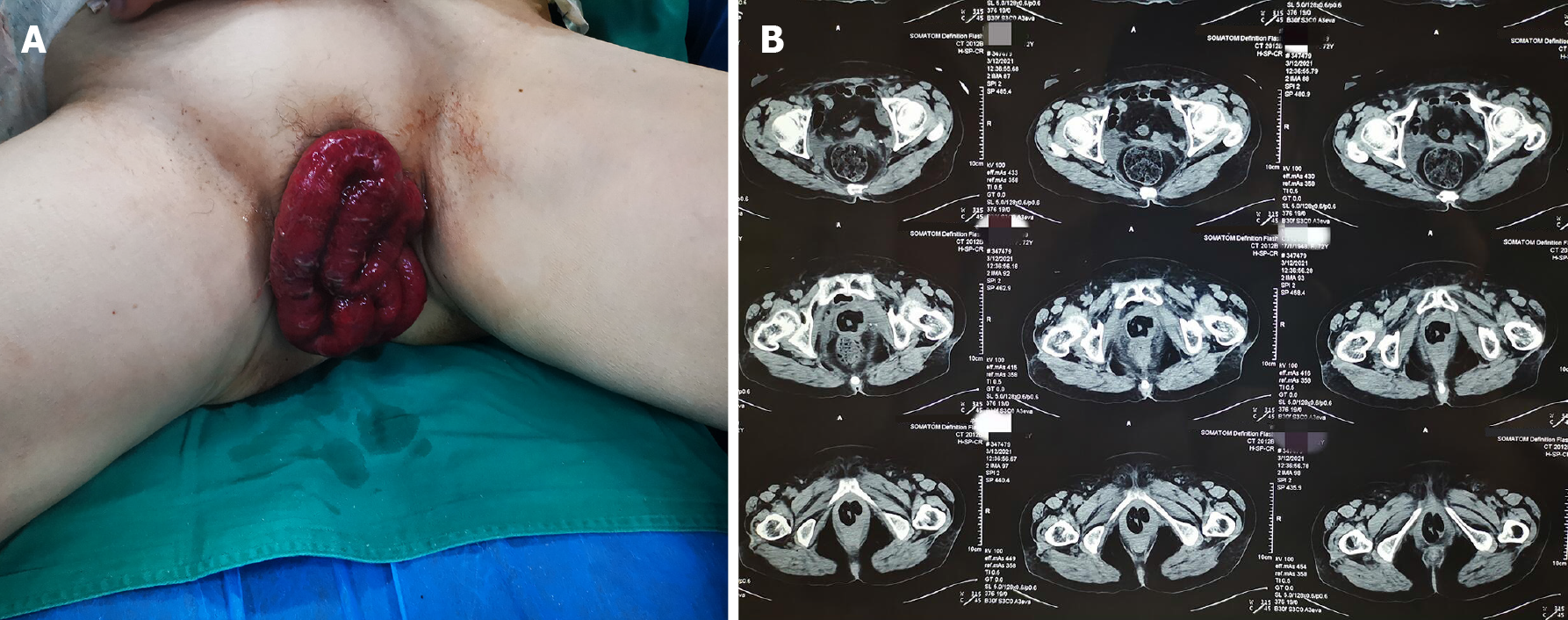

The patient’s temperature was 37.6°C, heart rate was 98 bpm, respiratory rate was 19 breaths per minute, blood pressure was 170/85 mmHg and oxygen saturation in room air was 99%. Physical examination after admission revealed that the small intestine had prolapsed approximately 20 cm, and its color was dark red (Figure 1). The initial diagnosis was vaginal enterocele (Aa6, Ba7, C9, AP-4, BP6 stage IV prolapse) according to the POP-Q system[6,7].

Blood analysis revealed mild leukocytosis of 11.5 × 109/L, with predominant neutrophils (85%) and a normal hematocrit and platelet count. Prothrombin and partial thromboplastin times were normal, and the d-dimer value was 0.71 μg/mL. Serum C-reactive protein was normal, and the erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 32 mm/h. The blood biochemistry and urine analyses were normal. The electrocardiogram, chest X-ray and arterial blood gas results were also normal.

In the initial imaging evaluation with a pelvic computed tomography (CT) scan, the patient’s uterus and bladder were not visualized. A partial small bowel herniation from the pelvic region was discovered (Figure 1B), and the abdominal CT showed no other abnormalities.

Wei Jiao, MD, PhD, Chief Doctor, Professor, Department of Urology, The Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University, provided the following assessment: The patient underwent laparoscopic radical cystectomy and hysterectomy 2 mo earlier. Based on the patient's medical history and physical examinations, acute vaginal enterocele was considered.

Yu-Fang Xia, MD, PhD, Chief Doctor, Assistant Professor, Department of Gynecology, The Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University, provided the following assessment: After undergoing radical cystectomy combined with hysterectomy, female patients may suffer from POP due to the destruction of pelvic structures. If the patient presents vaginal bacteria proliferation, damage to pelvic internal tissues due to inflammation resulting in edema can result in acute vaginal enterocele.

Guo-De Sui, MD, PhD, Chief Doctor, Assistant Professor, Department of Emergency Surgery, The Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University, provided the following assessment: The patient's physical examination after admission revealed that the small intestine had prolapsed approximately 20 cm, and its color was dark red (Figure 1). We were concerned that the patient might have bowel rupture, and open surgical exploration was urgently needed.

The final diagnosis of the presented case was acute vaginal enterocele after cystectomy.

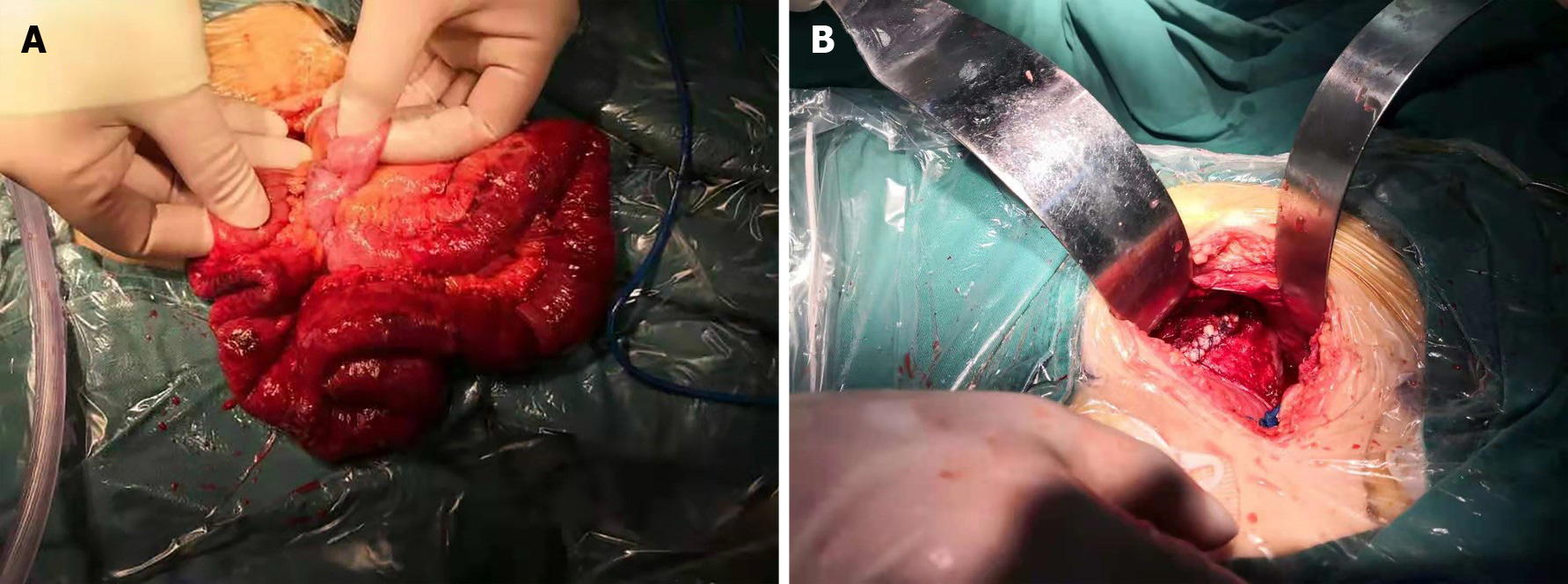

The patient's exposed small bowel outside the vagina was dark red, and due to the risk of small bowel ischemic necrosis and rupture, we quicky performed open surgical exploration to ensure that the small bowel was free of mesangial torsion and necrosis. Intraoperatively, an abdominal median incision approximately 10 cm in length was made in the abdominal cavity for exploration. The patient had no obvious adhesion in the abdominal cavity. A small amount of ascites was observed in the pelvic cavity, and the sigmoid colon was palpable with a larger mass of hard feces. Intraoperatively, approximately 20 cm of the small intestine was dislodged from the vaginal stump. After being placed back and moistened with warm saline for 15 min, the dislodged small intestine exhibited good revascularization and peristalsis (Figure 2A). A small portion of the intestinal wall serosal layer was broken. We used 4-0 VICRYL (Ethicon) for suture repair. The patient's vaginal stump exhibited edema and inflammatory changes, and the suture was reinforced using 0-0 VICRYL (Ethicon) (Figure 2B). After washing of the pelvic cavity with warm saline and dilute iodophor, the pelvic floor wound was assessed to ensure that it was not bleeding. The incision was closed layer by layer.

Postoperatively, we used cefoperazone sulbactam to prevent infection and observed that the patient's routine inflammatory indicators gradually recovered to normal levels 3 d after surgery. Routine blood tests returned to normal values before discharge, but mild anemia was noted. The patient began to flatulate on postoperative day 2 and defecate on postoperative day 3. The patient did not show symptoms such as intestinal root obstruction and intestinal necrosis during hospitalization. The patient recovered well and was discharged on the 5th postoperative day. During the follow-up assessment approximately 6 mo after the patient was discharged from the hospital, no new prolapse and no cancer recurrence were noted.

Currently, no definite incidence rate of POP after radical cystectomy has been reported. However, after radical cystectomy and hysterectomy, the rate of pelvic cavity structure prolapse is not minimal[8]. The patients mainly have chronic symptoms. Acute enterocele patients are rare, and clinicians lack relevant treatment experience. Both urgent and elective revision surgeries are difficult and require the skill of an experienced physician.

In our literature review, representative cases of acute and chronic POP after radical cystectomy (including cases treated with laparoscopic and robotic-assisted surgery) due to bladder cancer published in recent years were retrieved. Table 1 summarizes the patient's basic conditions, surgical approach, and follow-up in these cases. Most of the surgeries were performed using the vaginal approach. In addition, nonurgent repair surgery was supplemented with mesh reinforcement, and polytetrafluoroethylene polymer composites were the mesh material most often used. Some scholars, such as Lin et al[2], have also chosen to use biological grafts. Zimmer and Wang[9] believed that the placement of mesh reduces the chance of POP recurrence to some extent and benefits patients in the long term. The placement of a matched mesh by surgical repair is currently the most popular surgical approach for treating POP. However, there is a possibility of recurrence postoperatively. In the case reported by Lin, some patients experienced a second or even third recurrence after repair and ultimately opted for a more extreme complete vaginal suture procedure. Multiple recurrences of POP cause considerable harm to patients, both psychologically and physiologically, while also increasing their financial burden. We reviewed previous case reports and found that the main factors reported to be responsible are type of surgery and lack of judgment and corresponding preventive measures against the etiology of the disease. We propose some humble opinions in this regard.

| Ref. | Case | Age | Surgry | Time to pop after surgry | Type and stage | Approach | Method | Relaspe | Follow up |

| Okada et al[13] | 1 | 78 | Cystectomy and Hysterectomy | 3 mo | Stage III Anterior enterocele | Transvaginal | Suture with Polytetrafluoroethylene mesh | No | 6 mo |

| Shaker[8] | 1 | 75 | Cystectomy and Hysterectomy | 10 mo | Stage III Anterior enterocele | Transvaginal | Suture | No | 4 mo |

| Stav et al[14] | 1 | 70 | Cystectomy | 16 mo | Stage III Anterior enterocele | Transvaginal | Suture with polypropylene mesh | Yes | 2 mo |

| 2 | 71 | Cystectomy | 18 mo | Stage IV Anterior enterocele | Transvaginal | Suture | No | 10 mo | |

| 3 | 69 | Cystectomy,hysterectomy and Anterior vaginal repair | 10 mo | Stage IV Anterior enterocele | Transvaginal | Suture | No | 5 mo (Died) | |

| 4 | 44 | Cystectomy,ileal conduit and chemotherap | 2 mo | Stage III Anterior enterocele | Transvaginal | Suture with bilateral iliococcygeal suspension | Three weeks later developed a colo-vaginal fistula | 10 mo (Died) | |

| 5 | 65 | Cystectomy,ileal conduit | 7 mo | Stage IV Anterior enterocele | Transvaginal | Colpocleisis | Yes | 6 mo | |

| Graefe et al[15] | 1 | 67 | Cystectomy,ileal conduit | 8 mo | Stage IV Anterior enterocele | Transvaginal | Suture with Polypropylene mesh | No | 16 mo |

| 2 | 76 | Cystectomy,ileal conduit | 12 mo | Stage IV Anterior enterocele and vaginal vault prolapse | Transvaginal | Suture with Polypropylene mesh | No | 4 mo | |

| Lin et al[2] | 1 | 55 | Robotic-assisted cystectomy with ileal conduit (previous hysterectomy) | 4 mo | Stage IV with denuded anterior vaginal wall enterocele | Transvaginal | 6 wk later native tissue repair, 52 wk later Suture with biological graft, 78 wk completion perineorrhaphy | Yes, 6 wk later vaginal wall dehiscence 52 wk later recurrent dehiscence 78 wk recurrent dehiscence | 5 yr |

| 2 | 68 | Robotic-assisted cystectomy with ileal conduit (previous hysterectomy) | 1 yr | Stage II prolapse of the anterior wall and vault anterior vaginal wall prolapse | Transvaginal | 56 wk later suture and reconstruction for an enterocele prolapsing, 80 wk later partial vaginectomy, 86 wk suture with biological graft | Yes, 56 wk later anterior vaginal wall prolapse, 80 wk later recurrent vaginal bulge. 86 wk later recurrent bulge | 21 mo | |

| 3 | 73 | Robotic-assisted radical cystectomy, hysterectomy and ileal conduit | 14 wk | Anterior vaginal wall prolapse | Transvaginal | Suture | NO | 11 mo | |

| 4 | 73 | Robotic-assisted radical cystectomy hysterectomy | 28 mo | Vaginal eversion andvaginal dehiscence | Transvaginal | Suture and colpocleisis, levatorplasty, perineorrhaphy | Yes, 4 mo later vaginal dehiscence | 3 wk | |

| 5 | 79 | Robotic-assisted radical cystectomy hysterectomy | 11 wk | Vaginal dehiscenceanda window of thickened peritoneal tissue | Transvaginal | Suture and enterocele repair, colpocleisis and aperineorrhaphy | No | 8 mo |

We have summarized the etiology of acute enterocele based on reported cases as follows: (1) Patients were discharged from the hospital with mixed hygiene strategies and occasionally lacked the necessary perineal care, had vaginal bacteria proliferation, had damage to pelvic internal tissues due to inflammation resulting in edema, and had difficulties in securing vaginal posterior wall sutures due to edema and the weakened state of inflammatory tissues (which result in slippage of sutures); (2) As was found in the patients in these cases, a history of constipation was present in some patients with increased pressure in the pelvic cavity during bowel movements leading to enterocele; and (3) Clinicians mainly focus on tumor recurrence and prognosis, and reexamination is mainly based on imaging and biochemical examination. Reexamination often lacks a meticulous physical examination, and early enterocele is easily overlooked. In response to the above pathogenetic factors, we have focused on proposing corresponding preventive measures. Expedite the patient's postoperative recovery and reduce the risk of postoperative infection. In addition to the proper use of antimicrobials, prophylactic measures are routine in surgical procedures, such as avoiding intraoperative hypothermia in patients, controlling perioperative blood glucose, and adhering to strict aseptic procedures[10]. Patients should be referred to gynecologic perioperative practice for anti-infection options when undergoing radical cystectomy and hysterectomy. The most notable of these strategies is the disinfection of the vagina preoperatively and intraoperatively, and we recommend the preoperative use of a 1:5000 potassium permanganate dilution by sitting in a bath and flushing the vagina once each morning and night. Intraoperatively, the scope of skin disinfection of the perineal area should be appropriately expanded, and the vagina should be rinsed again using dilute iodophors. Cleaning agents may also include chlorhexidine. The above approach has been used to reduce the number of bacteria on the skin of the perineal region and in the vagina with the aim of alleviating the inflammatory reaction in the vaginal wall tissue during and after surgery, thereby alleviating tissue edema and reducing the risk of suture slippage in the posterior vaginal wall after surgery. In addition, in the instructions before discharge, patients need to be reminded to pay attention to perineal hygiene postoperatively and to change their underpants on a regular basis. Postoperatively, increased abdominal pressure is one of the predisposing factors for POP and can be induced by coughing, laughing, improper movement, and constipation. Compared with extrinsic factors, such as coughing, laughing, and participating in sports, constipation is often overlooked by clinicians and patients[11].

In the present case, the patient had a long history of constipation with vaginal enterocele occurring during defecation and a large, hard fecal mass was palpable in the sigmoid colon on intraoperative exploratory laparotomy. We believe that constipation is a high-risk factor for acute vaginal enterocele. Therefore, it is important to correct constipation problems, and we recommend routine bowel preparation before surgery and propose individualized postoperative bowel movement management protocols for patients with a history of constipation[12]. Patients are encouraged to use glycerin enemas postoperatively. Softened stools facilitate expulsion, and osmotic laxatives, such as polyethylene glycol, may also be used if necessary. When patients are reexamined postoperatively, clinicians should emphasize physical examination unconstrained by imaging and laboratory test results, though they are important measures to detect early POP.

We report a case of a female patient who presented with a sudden, spontaneous small bowel bulging into the vagina. Exploratory laparotomy, small bowel recovery and vaginal repair were performed. Acute enterocele is a relatively intractable problem for surgeons once it occurs. If the patient has a history of surgery, adhesions in the abdominal viscera may be present, increasing the difficulty of surgery. According to the patient's actual situation, a transabdominal or transvaginal surgical approach can be taken, We have referred to the treatment methods of other scholars including Okada, Stav, and Graefe[13-15], which had good guiding significance for us. In our case, we chose the potentially cumbersome intraperitoneal approach because of additional concerns about revascularization of the patient's bowel. In addition, inflammation, adhesions and pain all contribute to increased local tissue oxidative stress in patients. Oxidative stress is one of the principal factors associated with mesh foreign-body reactions[16]. Therefore, we did not place meshes to prevent aggravation of inflammation. However, we found that mesh placement in cases without inflammation may benefit patients[17]. Acute vaginal enterocele causes great distress to patients both psychologically and physiologically while increasing the financial burden on patients. We believe that adequate preoperative preparation along with detailed postoperative education is one of the important means to prevent this complication. Other means of prevention await further study.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Urology and Nephrology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Ghannam WM, Zharikov YO S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Scosyrev E, Noyes K, Feng C, Messing E. Sex and racial differences in bladder cancer presentation and mortality in the US. Cancer. 2009;115:68-74. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 196] [Cited by in RCA: 234] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lin FC, Medendorp A, Van Kuiken M, Mills SA, Tarnay CM. Vaginal Dehiscence and Evisceration After Robotic-assisted Radical Cystectomy: A Case Series and Review of the Literature. Urology. 2019;134:90-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Lee D, Zimmern P. Management of Pelvic Organ Prolapse After Radical Cystectomy. Curr Urol Rep 2019;20:71.. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Abou-Elela A. Outcome of anterior vaginal wall sparing during female radical cystectomy with orthotopic urinary diversion. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2008;34:115-121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Chang SS, Cole E, Cookson MS, Peterson M, Smith JA Jr. Preservation of the anterior vaginal wall during female radical cystectomy with orthotopic urinary diversion: technique and results. J Urol. 2002;168:1442-1445. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Bump RC, Mattiasson A, Bø K, Brubaker LP, DeLancey JO, Klarskov P, Shull BL, Smith AR. The standardization of terminology of female pelvic organ prolapse and pelvic floor dysfunction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:10-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3198] [Cited by in RCA: 3114] [Article Influence: 107.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Madhu C, Swift S, Moloney-Geany S, Drake MJ. How to use the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification (POP-Q) system? Neurourol Urodyn 2018;37:S39-43.. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Shaker D. Anterior enterocele: a cause of recurrent prolapse after radical cystectomy. Int Urogynecol J. 2020;31:219-220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Zimmern PE, Wang CN. Abdominal Sacrocolpopexy for Repair of Pelvic Organ Prolapse After Radical Cystectomy. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2019;25:218-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Wick EC, Hobson DB, Bennett JL, Demski R, Maragakis L, Gearhart SL, Efron J, Berenholtz SM, Makary MA. Implementation of a surgical comprehensive unit-based safety program to reduce surgical site infections. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;215:193-200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 11.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lapalus MG, Henry L, Barth X, Mellier G, Gautier G, Mion F, Damon H. [Enterocele: clinical risk factors and association with others pelvic floor disorders (about 544 defecographies)]. Gynecol Obstet Fertil. 2004;32:595-600. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Andresen V, Layer P. Medical Therapy of Constipation: Current Standards and Beyond. Visc Med. 2018;34:123-127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Okada Y, Matsubara E, Nomura Y, Nemoto T, Nagatsuka M, Yoshimura Y. Anterior enterocele immediately after cystectomy: A case report. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2020;46:2446-2449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Stav K, Dwyer PL, Rosamilia A, Lim YN, Alcalay M. Transvaginal pelvic organ prolapse repair of anterior enterocele following cystectomy in females. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2009;20:411-415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Graefe F, Beilecke K, Tunn R. Vaginal vault prolapse following cystectomy: transvaginal reconstruction by mesh interposition. Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24:1407-1409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Talley AD, Rogers BR, Iakovlev V, Dunn RF, Guelcher SA. Oxidation and degradation of polypropylene transvaginal mesh. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2017;28:444-458. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Chapple CR, Cruz F, Deffieux X, Milani AL, Arlandis S, Artibani W, Bauer RM, Burkhard F, Cardozo L, Castro-Diaz D, Cornu JN, Deprest J, Gunnemann A, Gyhagen M, Heesakkers J, Koelbl H, MacNeil S, Naumann G, Roovers JWR, Salvatore S, Sievert KD, Tarcan T, Van der Aa F, Montorsi F, Wirth M, Abdel-Fattah M. Consensus Statement of the European Urology Association and the European Urogynaecological Association on the Use of Implanted Materials for Treating Pelvic Organ Prolapse and Stress Urinary Incontinence. Eur Urol. 2017;72:424-431. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 17.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |