Published online Feb 26, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i6.2036

Peer-review started: September 26, 2021

First decision: October 18, 2021

Revised: October 28, 2021

Accepted: January 11, 2022

Article in press: January 11, 2022

Published online: February 26, 2022

Processing time: 150 Days and 3.4 Hours

Detergent poisoning mostly occurs through oral ingestion (> 85%), ocular exposure (< 15%), or dermal exposure (< 8%). Reports of detergent poisoning through an intravenous injection are extremely rare. In addition, there are very few cases of renal toxicity directly caused by detergents. Here, we report a unique case of acute kidney injury caused by detergent poisoning through an accidental intravenous injection.

A 61-year-old man was intravenously injected with 20 mL of detergent by another patient in the same room of a local hospital. The surfactant and calcium carbonate accounted for the largest proportion of the detergent. The patient complained of vascular pain, chest discomfort, and nausea, and was transferred to our institution. After hospitalization, the patient’s serum creatinine level increased to 5.42 mg/dL, and his daily urine output decreased to approximately 300 mL. Renal biopsy findings noted that the glomeruli were relatively intact; however, diffuse acute tubular injury was observed. Generalized edema was also noted, and the patient underwent a total of four hemodiafiltration sessions. Afterward, the patient’s urine output gradually increased whereas the serum creatinine level decreased. The patient was discharged in a stable status without any sequelae.

Detergents appear to directly cause renal tubular injury by systemic absorption. In treating a patient with detergent poisoning, physicians should be aware that the renal function may also deteriorate. In addition, timely renal replacement therapy may help improve the patient’s prognosis.

Core Tip: Reports of detergent poisoning through an intravenous injection are extremely rare. Here, we report a case of acute kidney injury caused by detergent poisoning through an accidental intravenous injection. The patient progressed to acute kidney injury after administration of detergent. Kidney biopsy showed diffuse acute tubular injury. This case demonstrates that detergent directly cause tubular injury by systemic absorption. In addition, this case shows that renal replacement therapy at an appropriate time is helpful for the patient’s prognosis.

- Citation: Park S, Ryu HS, Lee JK, Park SS, Kwon SJ, Hwang WM, Yun SR, Park MH, Park Y. Acute kidney injury due to intravenous detergent poisoning: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(6): 2036-2044

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i6/2036.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i6.2036

Detergent poisoning mostly occurs through oral ingestion (> 85%), ocular exposure (< 15%), or dermal exposure (< 8%)[1]. According to a previous study, 36% of the cases of chemical poisoning were caused by detergents; in most cases, children accidentally ingested the detergents[2]. Ingesting detergents primarily causes gastrointestinal symptoms such as oral cavity hyperemia, pharyngeal irritation/pain, drooling, and vomiting[3,4]. Although rare, respiratory depression[3,5], central nervous system depression [6], and metabolic acidosis with hyperlactatemia[7] have been reported.

Reports of renal toxicity due to detergent ingestion are rare. A previous report noted that acute kidney injury (AKI) occurred due to rhabdomyolysis[8], while another noted that AKI occurred without any signs of rhabdomyolysis. The authors suggested that the systemic absorption of the detergent resulted in the direct toxicity of the renal tubules, causing AKI[9]. Another report of renal cortical necrosis after detergent ingestion showed that acute tubular necrosis and thrombotic microangiopathy were noted in renal biopsy[10].

Reports of detergent poisoning through an intravenous injection are extremely rare[11]. In addition, there are very few cases of renal toxicity directly caused by detergents[9,10]. Therefore, our report discusses a case of AKI caused by an intravenous injection of detergent.

A 61-year-old man was injected with detergent through the venous line and presented to the emergency department of our institution complaining vascular pain, dizziness, nausea, and chest discomforts.

The patient was admitted to a local hospital two months ago because of second degree burn. While undergoing burn treatment, another patient in the same room injected an unknown bubbling liquid through the patient’s venous line in the left greater saphenous vein, under the pretext of clearing the blocked fluid line. Within minutes of being injected with detergent, the patient complained of vascular pain, dizziness, nausea, and chest discomforts. He was then prompted admission to the emergency department of our institution.

The National Forensic Service compared the components of the liquid in the patient’s intravenous infusion line and the bathroom detergent in the hospital room of the local hospital. The detergent contained the following ingredients: Surfactant (dodecyldimethylamine oxide, sodium alkylbenzene sulfonate), stabilizer (water, ethanol, octane-1,2-diol, sodium sulfate, silicon dioxide), cleaning aid (sodium hydrogen carbonate), antifoam (dimethylsiloxane), abrasive (calcium carbonate), and perfume (2,6-dimethyl-7-octen-2-ol, linalool, (E)-dodec-2-en-1-al, (R)-p-mentha-1,8-dien) (Table 1). The surfactant and calcium carbonate, which accounted for the largest proportion, were also detected in the intravenous infusion line. It was revealed that approximately 20 mL of detergent was injected.

| Ingredients | Molecular weight (g/moL) |

| Dodecyldimethylamine oxide | 229.40 |

| Sodium alkylbenzene sulfonate | 334.45 |

| Water | 18.02 |

| Ethanol | 46.07 |

| Octane-1,2-diol | 146.23 |

| Sodium sulfate | 142.04 |

| Silicon dioxide | 60.08 |

| Sodium hydrogen carbonate | 84.01 |

| Dimethylsiloxane | 92.17 |

| Calcium carbonate | 100.09 |

| 2,6-dimethyl-7-octen-2-ol | 156.27 |

| Linalool | 154.25 |

| (E)-dodec-2-en-1-al | 182.30 |

| (R)-p-mentha-1,8-dien | 136.23 |

The patient was maintained on atorvastatin 10 mg for dyslipidemia.

The patient has no relevant family history.

At the emergency department, the patient’s vital signs showed the following: Blood pressure, 120/60 mmHg; heart rate, 88 beats per minute; respiratory rate, 14 per minute; body temperature, 36.1 °C. On physical examination, the breath sounds were clear, and the heart rhythm was regular without murmurs. Erythema was observed around the left greater saphenous vein.

The initial laboratory findings revealed mild leukocytosis (14.8 × 103/μL) and elevated levels of aspartate transaminase (AST) (111 IU/L), total and direct bilirubin (3.48 mg/dL and 1.02 mg/dL, respectively), and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) (1726 IU/L) (Table 2). Arterial blood gas analysis did not show metabolic acidosis or hyperlactatemia. The dipstick urinalysis results revealed protein 3+ and blood 3+, and urine microscopy revealed the presence of numerous red blood cells (RBCs) (Table 3).

| Parameters | 1st day of hospitalization | 2nd day of hospitalization | 3rd day of hospitalization |

| WBC (× 103/μL) | 14.8 | 9.9 | 6.5 |

| Hb (g/dL) | 12.6 | 10.1 | 10.7 |

| PLT (× 103/μL) | 149 | 109 | 110 |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 23.7 | 44.0 | 55.7 |

| Cr (mg/dL) | 0.99 | 3.59 | 5.42 |

| AST (IU/L) | 111 | 51 | 31 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 22 | 8 | 4 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 3.48 | 0.84 | 0.57 |

| Direct bilirubin (mg/dL) | 1.02 | - | - |

| LDH (IU/L) | 1726 | 833 | 731 |

| CPK (IU/L) | 56 | - | 36 |

| Ca (mg/dL) | 9.61 | 9.06 | 9.10 |

| Inorganic P (mg/dL) | 3.77 | 5.16 | 4.59 |

| Na (mEq/L) | 139 | 136 | 137 |

| K (mEq/L) | 3.76 | 3.82 | 4.02 |

| CI (mEq/L) | 104.2 | 103.1 | 103.7 |

| Total CO2 (mmol/L) | 25.1 | 22.9 | 22.5 |

| The dipstick urinalysis findings | |

| Color | Orange |

| Turbidity | Cloudy |

| Specific gravity | 1.044 |

| pH | 6.5 |

| Protein | 3+ |

| Glucose | - |

| Ketone | - |

| Blood | 3+ |

| Urobilinogen | - |

| Bilirubin | - |

| Nitrite | - |

| WBC | - |

| Urine microscopy findings | |

| Micro RBC (/HPF) | Many (> 20) |

| Micro WBC (/HPF) | 0-2 |

| Micro sediment | No cast and crystal |

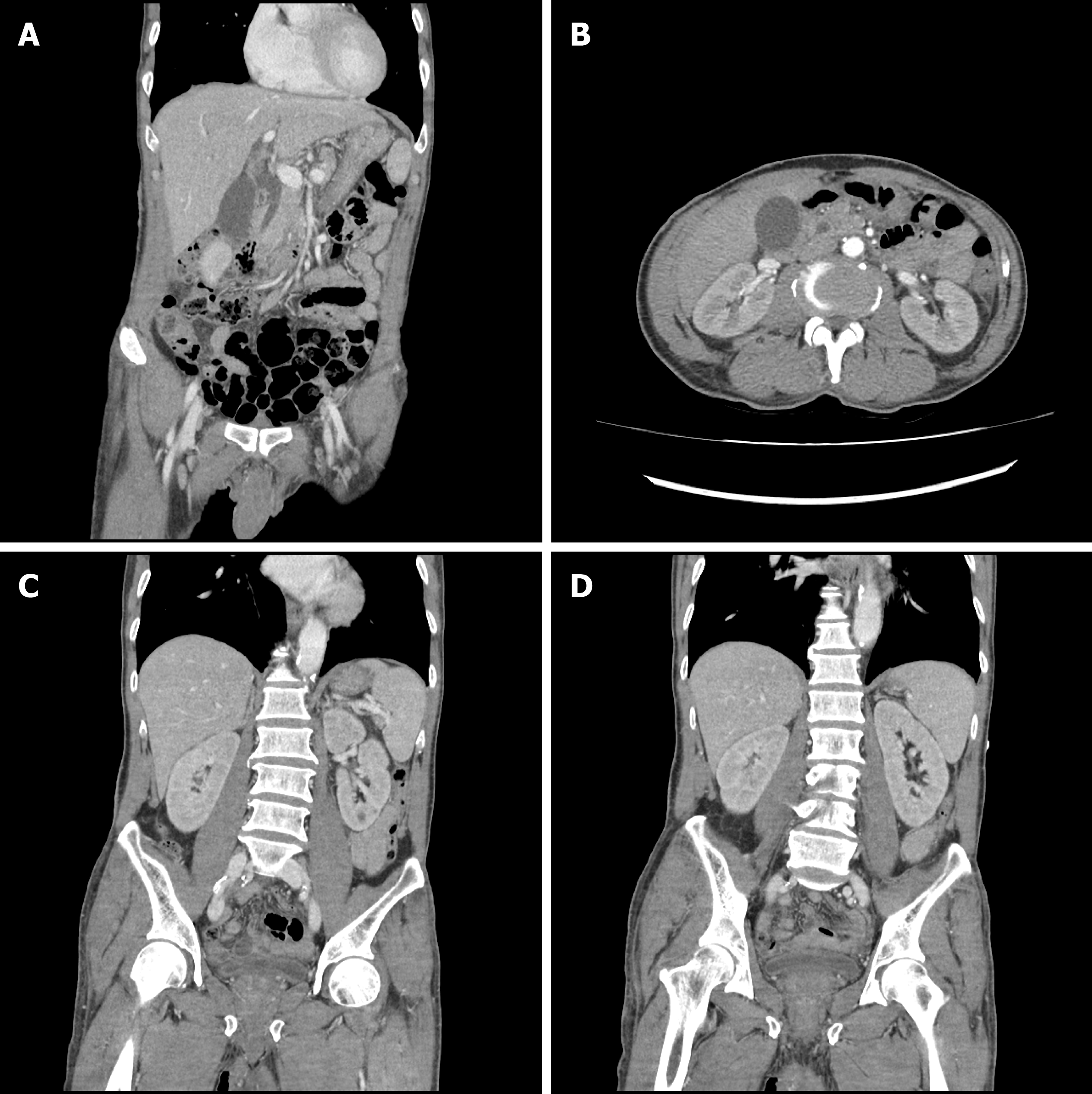

The chest radiography and electrocardiogram readings showed no abnormal findings. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis was performed to determine the cause of bilirubin elevation. The CT images revealed mild common bile duct dilatation, which was seen as a senile change, and the absence of any lesions that could elevate the bilirubin level. The kidney sizes and shapes were relatively normal, but both renal parenchymal enhancements were decreased, which was suggestive of AKI (Figure 1).

On the 2nd day of hospitalization, the patient complained of general weakness and nausea. A decrease in hemoglobin from 12.6 mg/dL to 10.1 mg/dL was observed in laboratory findings on the 2nd day of hospitalization. LDH, AST, and bilirubin elevation were observed in the initial laboratory findings, and since hemolysis may be caused by detergent[12,13], further diagnostic work up was performed. Peripheral blood smear showed normal RBCs and reticulocyte counts without schistocytes. Serum haptoglobin level was also within normal range (Table 4).

| Tests | 2nd day of hospitalization | |

| Peripheral blood smear | RBC | Normocytic and normochromic RBCs with mild anisopoikilocytosis |

| WBC | Normal WBC counts with no toxic granulation and vacuolations | |

| PLT | Decreased PLT counts | |

| Reticulocyte count (%) | 1.6 | |

| Hemosiderin stain | Negative | |

| Haptoglobin (mg/dL) | 45 | |

| Homocysteine (μmol/L) | 8.66 | |

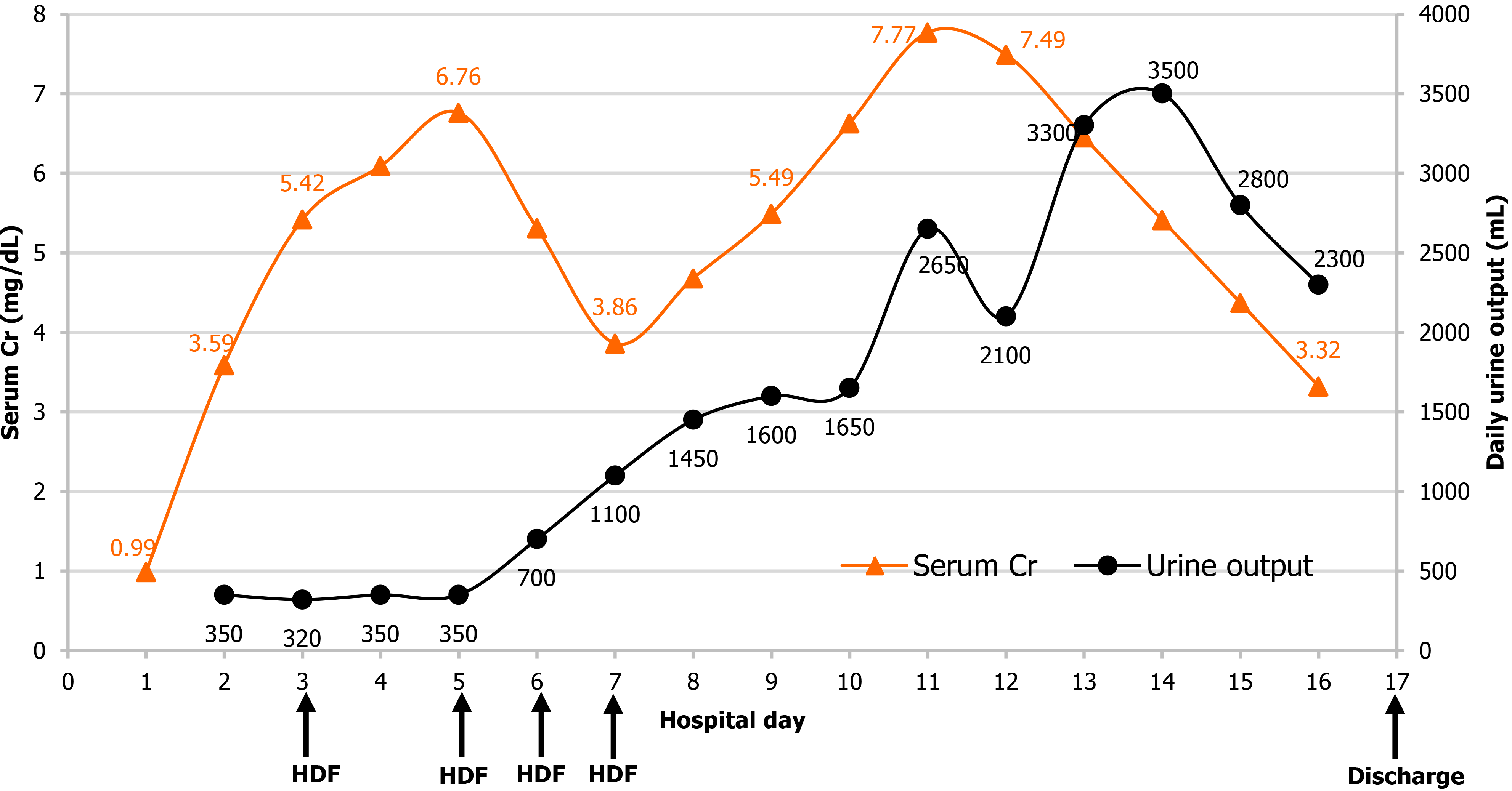

White blood cell count, AST, bilirubin, and LDH, which were increased in the initial laboratory findings, all decreased at the 2nd day of hospitalization; however, blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and serum creatinine (Cr) levels were increased to 44.0 mg/dL and 3.59 mg/dL, respectively. Oliguria was noted as the patient’s daily urine output was only 350 mL. On the 3rd day of hospitalization, the BUN and serum Cr levels further increased to 55.7 mg/dL and 5.42 mg/dL, respectively. Oliguria (daily urine output 320 mL) persisted and generalized edema, which did not respond to diuretics, was noted.

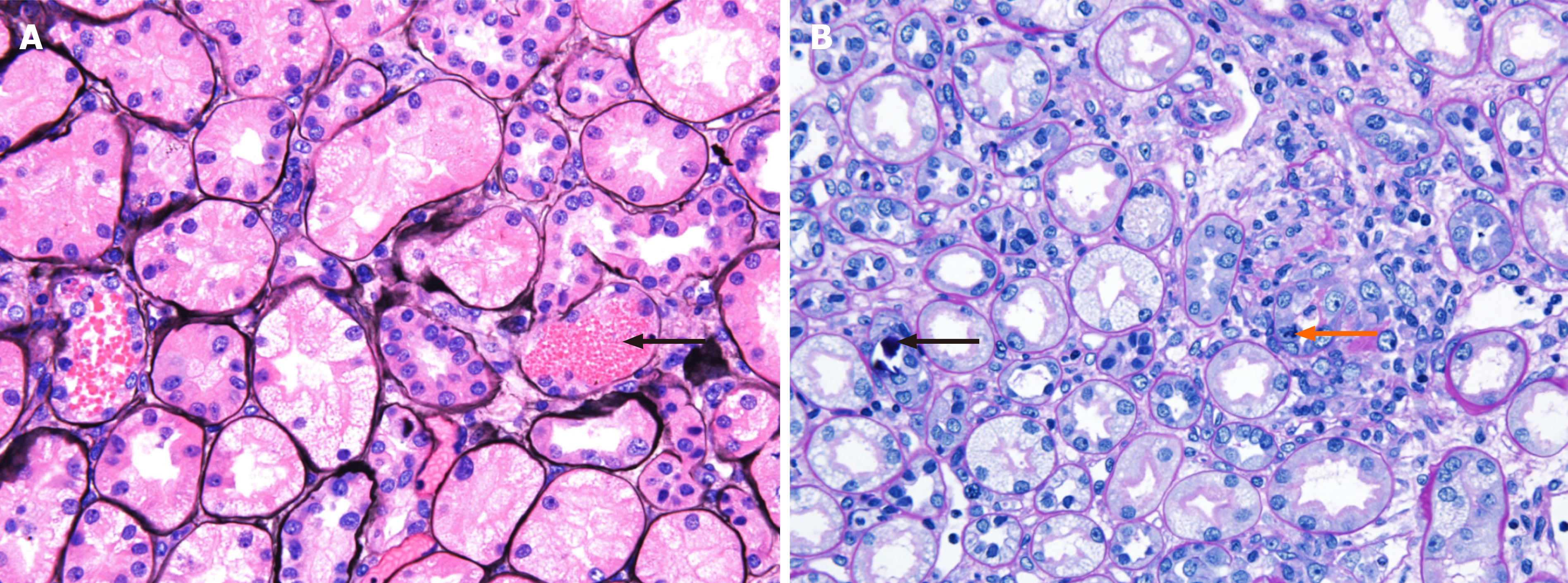

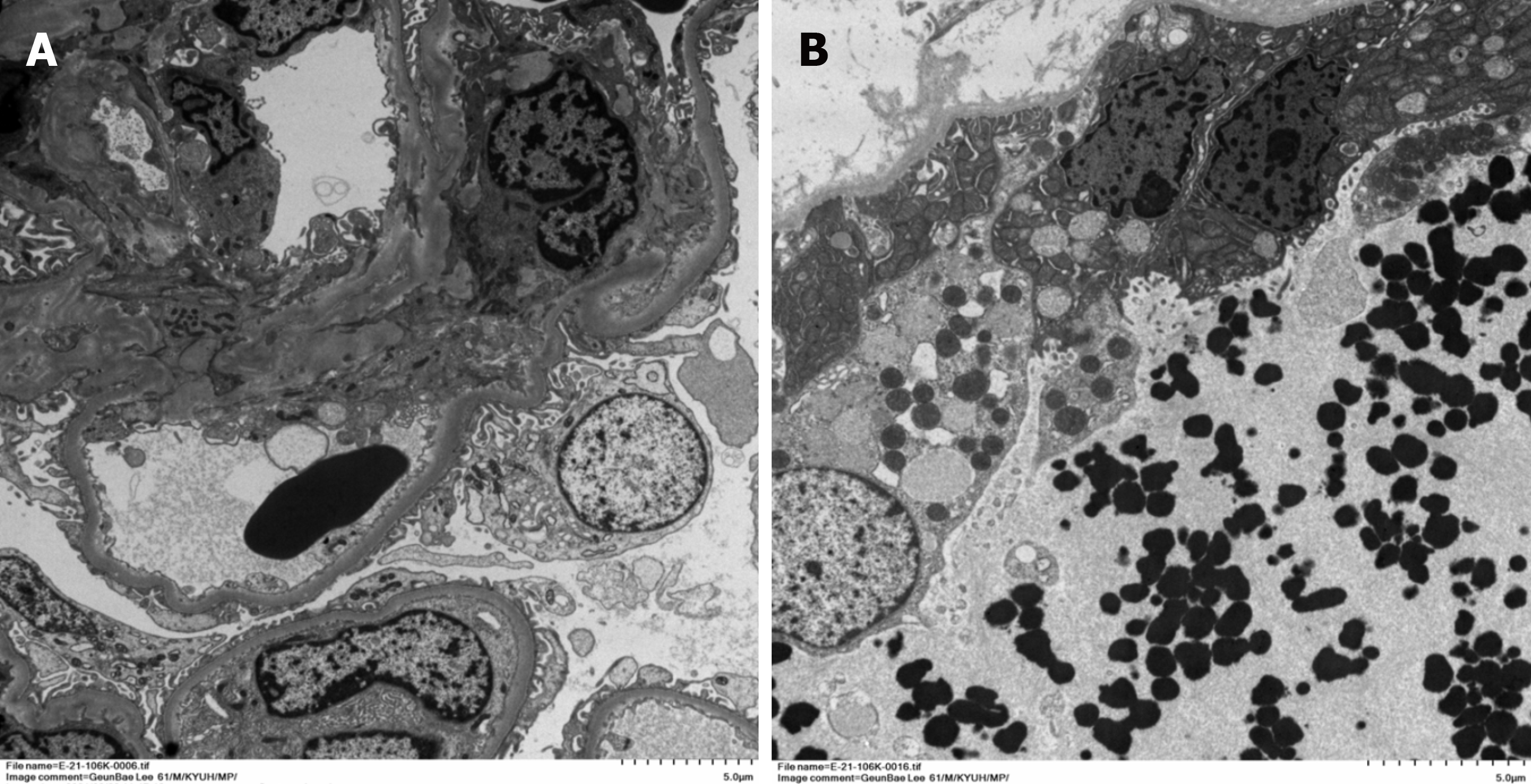

Renal biopsy was performed on the 4th day of hospitalization. Light microscopy examination of renal biopsy specimen revealed up to 15 glomeruli that appeared normal in size and cellularity. The tubules showed diffuse swollen cytoplasms with vacuolar degeneration, focal loss of brush border with focal regenerative nuclear change and mitotic figures. Some tubular lumina contain a few RBCs and granular casts, sloughed cells and calcium concretions. There were focal interstitial fibrosis and infiltration of lymphocytes and some neutrophils. Segmental trace immunofluorescence staining for IgG, IgM and fibrinogen in mesangium was suggestive of a nonspecific trapping. Electron microscopic examination revealed tubular degeneration and granular casts in distal tubular lumina. Thus, the diagnosis was diffuse acute tubular injury (Figures 2 and 3).

The final diagnosis of the presented case is acute kidney injury due to direct renal tubular injury by detergent injection.

On the day after admission, the patient presented with oliguria and generalized edema that did not respond to diuretics. Thus, on the 3rd day of hospitalization, we performed hemodiafiltration (HDF) to treat the volume overload and to remove the potential toxic substances in the blood.

The patient underwent four sessions of HDF until the 7th day of hospitalization. Once his urine output increased and the edema improved, HDF was discontinued, and he was closely monitored. The serum Cr level, which was still elevated until the 11th day of hospitalization, gradually decreased and was seen as a sign of recovery of his renal function. Symptoms such as general weakness and generalized edema were not noted, and he was discharged on the 17th day of hospitalization (Figure 4).

The patient’s symptoms and serum Cr level showed improvement from the 12th day of hospitalization, and the patient discharged on the 17th day without any sequelae. One week after discharge, the serum Cr level (0.83 mg/dL) returned to normal, and the urinalysis results did not reveal proteinuria or hematuria.

This is a case of AKI caused by an intravenous detergent injection in which the renal biopsy findings revealed acute tubular injury. Detergent poisoning commonly occurs through the oral route, and this is the first case of detergent poisoning through an intravenous injection in the Republic of Korea.

To the best of our knowledge, there has only been one case report of detergent poisoning through an intravenous injection in the literature. Okumura et al[11] reported a case of a patient injecting 40 mL of detergent into his vein during a suicide attempt. Unlike our patient, this patient showed more serious clinical features including ventricular tachycardia, AKI, rhabdomyolysis, hemolysis, and coagulation dysfunction. The renal biopsy findings of this patient were acute tubular necrosis without any other abnormality, similar to our patient. The differences between the previous case and our case are the components and amounts of detergent (40 mL vs 20 mL, respectively). The detergent in the previous case was composed of 8% surfactant (alkylbetain, sodium fatty acid, alkanol amide, sodium alkylether sulfate, benzalkonium salt, and alkylglycoside). Although there was no information on the other ingredients, the surfactant itself was different from our case. The differences in the components and administered amounts of detergent may have resulted in the different clinical features of each case.

Rhabdomyolysis after the oral ingestion of a detergent has been reported to cause AKI[8]; however, this was not observed in our patient (Table 2). The creatine phosphokinase levels were consistently within normal range from hospitalization to discharge. The patient’s body temperatures were within the normal range during hospitalization, no signs of infection were observed, and the results of the blood cultures were negative. Therefore, the possibility of AKI due to infection was also thought to be scarce. In the previous case report, it was reported that AKI occurred without any factors that could cause secondary AKI such as rhabdomyolysis. The authors suggested that the tubular injury was directly caused by the systemic absorption of the detergent[9]. Similarly, our case had no other secondary cause of AKI other than acute tubular injury, which was the main clinical feature. Therefore, it is likely that direct tubular toxicity occurred in our patient.

There are some studies on the interactions between surfactants and the cell membrane[14]. Surfactants have a hydrophobic and hydrophilic part. It is believed that the hydrophobic component can partition into the lipophilic part of the membrane and increase its fluidity, leading to cell disruption and leakage, and cell death[15]. This mechanism may explain why surfactants cause hemolysis[16] and death of Escherichia coli[17]. However, there was no evidence of hemolysis in our case, and the AST and bilirubin elevation were occurred due to direct hepatotoxicity of detergent, presumably. The results of renal biopsy suggest that the detergent caused the destruction of the kidney tubules. Therefore, it can be considered that the surfactant of the detergent acted on the cell membranes of the kidney tubules and caused acute tubular injury. However, it is difficult to determine why other cells such as RBCs or myocytes were not affected. Calcium carbonate also accounted for a large proportion of the detergent injected into our patient. Excessive use of calcium carbonate can lead to milk-alkali syndrome and cause AKI[18]. However, our patient’s serum calcium level was within the normal range (Table 2). Thus, it seems unlikely that calcium carbonate caused AKI in our case.

We performed HDF for control of intractable generalized edema and removal of remained potential toxic substances from the patient’s blood. However, considering the molecular weight of the detergent’ component investigated retrospectively (Table 1), conventional hemodialysis (HD) and HDF could have had no difference in potential toxin removal capacity.

Although detergent poisoning through an intravenous injection is very rare, its components could cause direct renal toxicity. Therefore, regardless of the route, detergent poisoning can cause renal toxicity. When detergent poisoning occurs, the renal function should be closely monitored, and the timing of renal replacement therapy may improve the patient’s survival.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Urology and nephrology

Country/Territory of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Awad AK, de Melo FF, Udomkarnjananun S, Zhao L S-Editor: Xing YX L-Editor: A P-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Day R, Bradberry SM, Thomas SHL, Vale JA. Liquid laundry detergent capsules (PODS): a review of their composition and mechanisms of toxicity, and of the circumstances, routes, features, and management of exposure. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2019;57:1053-1063. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Alzahrani SH, Ibrahim NK, Elnour MA, Alqahtani AH. Five-year epidemiological trends for chemical poisoning in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Ann Saudi Med. 2017;37:282-289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Day R, Bradberry SM, Jackson G, Lupton DJ, Sandilands EA, H L Thomas S, Thompson JP, Vale JA. A review of 4652 exposures to liquid laundry detergent capsules reported to the United Kingdom National Poisons Information Service 2008-2018. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2019;57:1146-1153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Settimi L, Giordano F, Lauria L, Celentano A, Sesana F, Davanzo F. Surveillance of paediatric exposures to liquid laundry detergent pods in Italy. Inj Prev. 2018;24:5-11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Banner W, Yin S, Burns MM, Lucas R, Reynolds KM, Green JL. Clinical characteristics of exposures to liquid laundry detergent packets. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2020;39:95-110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. |

Rigaux-Barry F, Patat A-M, Cordier L, Manel J, Sinno-Tellier S: Risks related to pods exposure compared to traditional laundry detergent products: Study of cases recorded by French PCC from 2005 to 2012.

|

| 7. | Vohra R, Huntington S, Fenik Y, Phan D, Ta N, Geller RJ. Exposures to Single-Use Detergent Sacs Reported to a Statewide Poison Control System, 2013-2015. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2020;36:e690-e694. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Prabhakar KS, Pall AA, Woo KT. Rhabdomyolysis and acute renal failure complicating detergent ingestion. Singapore Med J. 2000;41:182-183. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Lim YC. Acute renal failure following detergent ingestion. Singapore Med J. 2009;50:e256-e258. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Riella LV, Golla S, Dogaru G, Rennke HG, Christopher K. Renal cortical necrosis complicating laundry detergent ingestion. NDT Plus. 2009;2:40-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Okumura T, Suzuki K, Yamane K, Kumada K, Kobayashi R, Fukuda A, Fujii C, Kohama A. Intravenous detergent poisoning. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 2000;38:347-350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Chernitsky E, Senkovich O. Mechanisms of anionic detergent-induced hemolysis. Gen Physiol Biophys. 1998;17:265-270. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Chernitsky EA, Senkovich OA. Erythrocyte hemolysis by detergents. Membr Cell Biol. 1997;11:475-485. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Groot RD, Rabone KL. Mesoscopic simulation of cell membrane damage, morphology change and rupture by nonionic surfactants. Biophys J. 2001;81:725-736. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 829] [Cited by in RCA: 711] [Article Influence: 29.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. |

Denyer SP, Stewart G: Mechanisms of action of disinfectants.

|

| 16. | Kondo T, Tomizawa M. Hemolysis by nonionic surface-active agents. J Pharm Sci. 1968;57:1246-1248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Das J, Rabone K. Antimicrobial cleaning compositions containing aromatic alcohols or phenols. Int Patent Appl. 1998;. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 18. | Skjønsberg H, Hartmann A, Fauchald P. [Acute renal failure caused by hypercalcemia]. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2001;121:1781-1783. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |