Published online Feb 26, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i6.2030

Peer-review started: September 15, 2021

First decision: October 18, 2021

Revised: October 31, 2021

Accepted: January 11, 2022

Article in press: January 11, 2022

Published online: February 26, 2022

Processing time: 161 Days and 4.1 Hours

Colonoscopy is essential for the diagnosis of intestinal Behcet’s disease (BD), which is characterized by a typical oval-shaped ulcer in the ileocecal region. However, potential risks of colonoscopy have rarely been reported.

Herein, we describe a patient with intestinal BD who presented with decreased oxygen saturation and shortness of breath during a diagnostic colonoscopy. Bilateral pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum, pneumoperitoneum, pneumoretroperitoneum and subcutaneous emphysema of the neck, chest, abdomen, back and scrotum were confirmed by computed tomography scan. The sudden change in condition was considered to be associated with iatrogenic bowel perforation. After receiving closed thoracic drainage and conservative therapy, the patient was discharged in stable condition.

Endoscopists should be aware of the risks of colonoscopy in patients with intestinal BD and the possibility of pneumothorax associated with intestinal perforation and make adequate preparations before colonoscopy.

Core Tip: Colonoscopy is necessary for diagnosing intestinal Behcet’s disease and determining the severity of gastrointestinal involvement. Endoscopists should be aware of the potential risks of colonoscopy in patients with intestinal Behcet’s disease and the possibility of pneumothorax associated with intestinal perforation.

- Citation: Mu T, Feng H. Bilateral pneumothorax and pneumomediastinum during colonoscopy in a patient with intestinal Behcet’s disease: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(6): 2030-2035

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i6/2030.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i6.2030

Intestinal Behcet’s disease (BD) is a rare, chronic, relapsing inflammatory disorder. As a special type of BD, it is characterized by a typical oval-shaped ulcer in the ileocecal region in addition to recurrent oral and genital ulcers, ocular and skin lesions, and a positive pathergy test[1]. Abdominal pain, diarrhea and hematochezia are common complaints[1]. Spontaneous bowel perforation is also a complication that could lead to intra-abdominal infection and even death[2].

Colonoscopy is necessary for diagnosing intestinal BD and determining the severity of gastrointestinal involvement. However, potential risks have rarely been mentioned in previous studies. In this article, we report a case of colonic perforation during diagnostic colonoscopy in a patient diagnosed with intestinal BD in which bilateral pneumothorax and respiratory distress occurred.

The patient presented with intermittent abdominal pain and bloating for six months and sudden shortness of breath and confusion during diagnostic colonoscopy.

A 58-year-old man presented with intermittent abdominal pain, bloating and reduced defecation in the past six months. To determine the severity of intestinal lesions and rule out intestinal tumors, the patient underwent a routine diagnostic colonoscopy using air insufflation under nontracheal intubation intravenous general anesthesia (propofol). Upon withdrawal of the colonoscope, the patient suddenly experienced shortness of breath and confusion and gradually developed cyanosis.

The patient underwent a colonoscopy 12 years prior, and colonic ulcers were observed. Because the patient had oral and perianal ulcers and the colonic ulcers were considered to be a manifestation of intestinal BD, the patient was diagnosed with intestinal BD by a rheumatologist. He had suffered severe pain in the right lower abdomen 11 years prior. Acute appendicitis was initially suspected, but spontaneous ileocecal perforation was confirmed during an emergency exploratory laparotomy, and surgical repair of the ileocecal perforation was performed. He still suffered from the recurrence of oral and perianal ulcers but did not experience unbearable abdominal symptoms after taking prednisone and leflunomide irregularly.

The patient had a 30-year history of smoking (1 pack per day).

The physical examination upon admission showed tenderness in the right lower abdomen. When cyanosis occurred, the oxygen saturation dropped to 68%, and the heart rate was 130 beats/min. Assisted mask ventilation was initiated with 100% oxygen, but the patient’s saturation did not improve. An abdominal examination revealed a distended abdomen on palpation and drum sounds on percussion. On auscultation, breath sounds were absent on the right side and diminished on the left side of the chest.

The patient had an antinuclear antibody titer of 1:320 (granular type, cytoplasmic type) and a positive fecal occult blood test upon admission. The laboratory results were not available during rescue.

The computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis before colonoscopy revealed bowel wall thickening in the terminal ileum, ileocecal area and appendix, ileocecal stenosis and incomplete bowel obstruction.

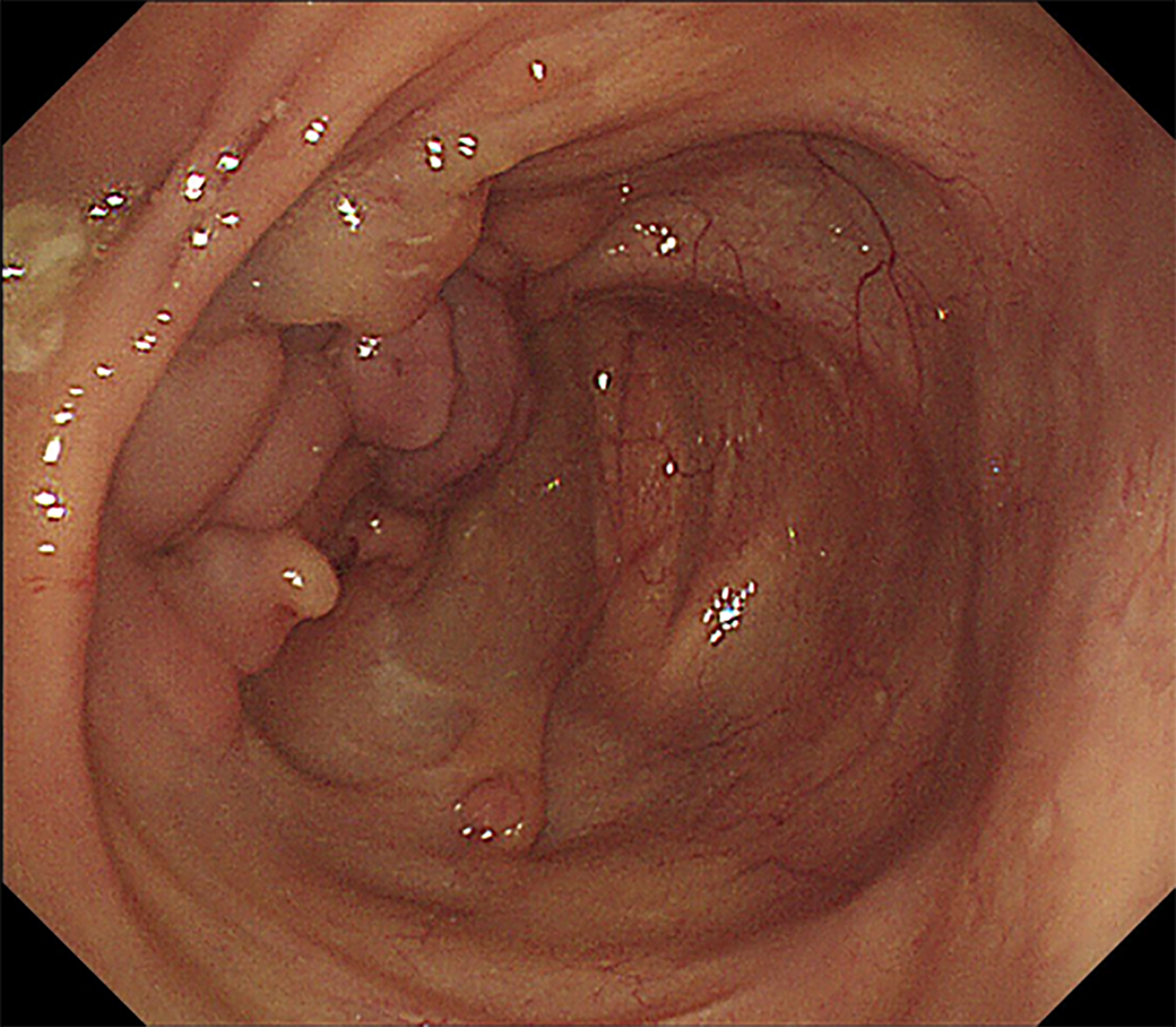

Colonoscopy revealed deformation, mucosal hyperplasia and multiple deep ulcers in the ileocecal region (Figure 1). The possibility of perforation could not be ruled out. The colonoscope could not enter the small intestine due to stenosis and deformation of the ileocecal valve. Pseudopolyps in the ascending colon and ring ulcers in the transverse colon and descending colon were also shown on colonoscopy. Biopsies were taken from the ileocecal region, ascending colon and transverse colon. Pathology revealed chronic active mucosal inflammation in the ileocecal region and chronic mucosal inflammation in the ascending and transverse colon.

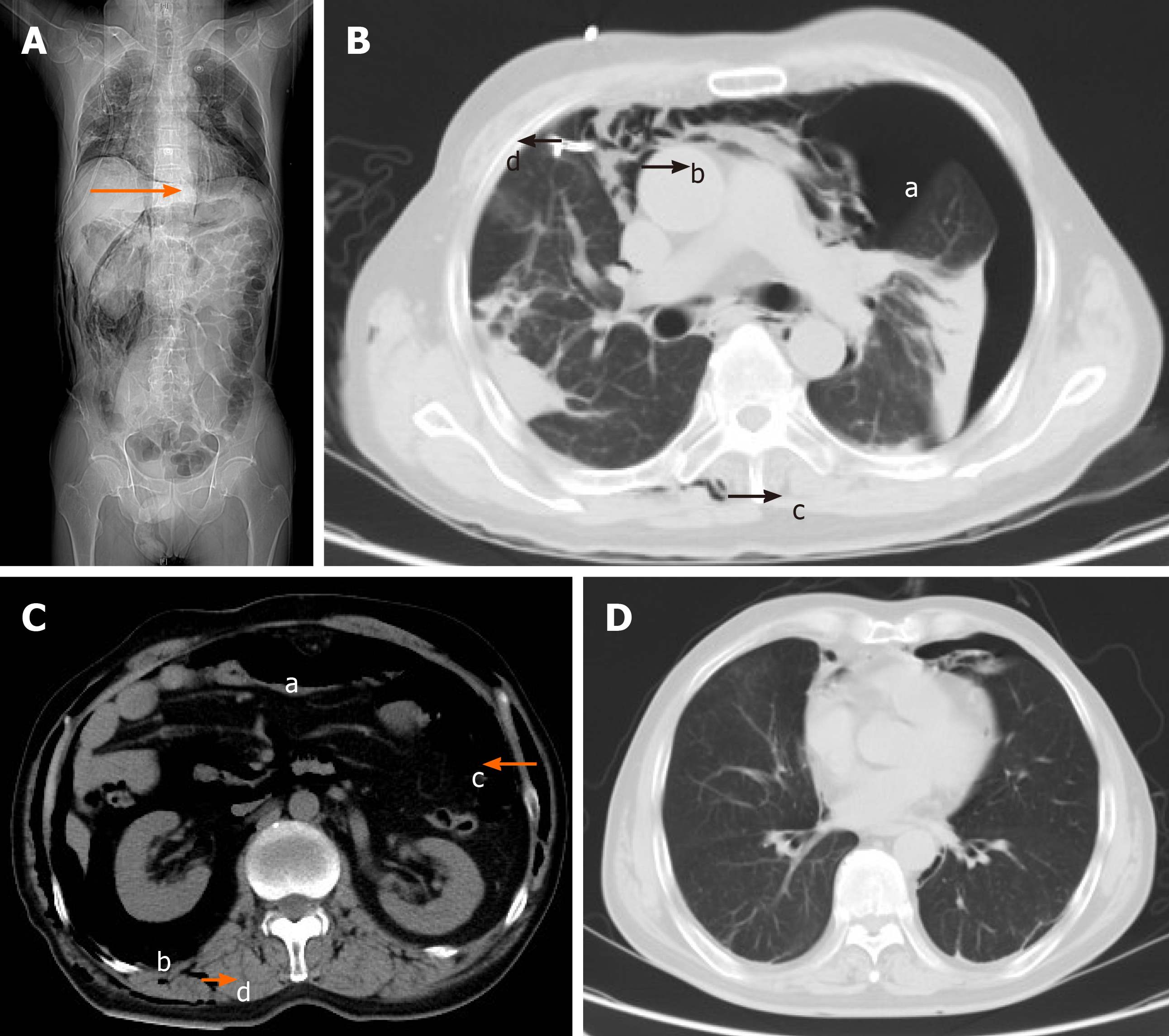

The CT scan of the chest, abdomen and pelvis after chest drain tube insertion showed bilateral pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum, pneumoperitoneum, pneumoretroperitoneum and subcutaneous emphysema of the neck, chest, abdomen, back and scrotum (Figure 2A-C).

The final diagnosis of the presented case was bowel perforation during the colonoscopy, resulting in bilateral pneumothorax, which is a life-threatening complication. The biopsies were taken from the mucosa at the edge of the ulcers without damage to the muscle layer, and no perforation after the biopsies was seen on endoscopy. Due to the past history of spontaneous ileocecal perforation and the presence of ileocecal stenosis and deep ulcers, it was speculated that this perforation occurred in the ileocecal area and was caused by a pressure-related injury to the muscle layer of the deep ulcers induced by air insufflation during the endoscopy.

Orotracheal intubation was immediately attempted by the anesthesiologists after the patient suffered shortness of breath and confusion but failed due to recurrent oral ulcers. Meanwhile, diagnostic abdominal paracentesis and thoracentesis were performed, and pneumothorax and pneumoperitoneum were confirmed. With the release of gas in the pleural cavity, the patient’s oxygen saturation gradually increased, and he gradually recovered consciousness. Therefore, orotracheal or nasotracheal intubation was not required in the subsequent treatment. We urgently contacted the thoracic surgeon, and the right thoracic drainage tube was subsequently inserted. Then, the patient’s vital signs were stable. To confirm the diagnosis, the patient was transferred to the imaging department for an emergency CT scan, the results of which are described above (Figure 2A-C). The thoracic surgeon reassessed the patient and considered that the left pneumothorax could be absorbed without inserting the left thoracic drainage tube. Then, the patient received conservative therapy (antibiotics and parenteral nutrition).

After rescue, the patient did not experience fever or severe abdominal pain. The white blood cell count was 11.87 × 109/L, C-reactive protein level was 22.00 mg/L, and procalcitonin level was 0.24 ng/mL on the day of the perforation. The chest drainage tube was removed 3 d after perforation. The white blood cell count was 6.92 × 109/L, C-reactive protein level was 20.75 mg/L, and procalcitonin level was 0.18 ng/mL 7 d after perforation. The CT scan of the chest, abdomen and pelvis 7 d after the perforation showed significant improvement of bilateral pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum, pneumoperitoneum, pneumoretroperitoneum and subcutaneous emphysema (Figure 2D). The patient stopped receiving total parenteral nutrition and consumed a liquid diet 8 d after perforation. He was satisfied with our rescue and discharged 9 d after perforation. Then, he took azathioprine to treat BD under the guidance of a rheumatologist.

Intestinal oval-shaped deep ulcers are characteristic lesions in patients with intestinal BD that can involve the intestinal muscle layer. Therefore, bowel perforation, especially ileocecal perforation, may occur as a complication of intestinal BD. In this case, spontaneous ileocecal perforation had occurred 11 years prior. Unfortunately, life-threatening iatrogenic bowel perforation associated with colonoscopy occurred during this admission.

Adult patients with spontaneous bowel perforation usually have specific causes, such as Crohn’s disease, scleroderma, intestinal non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and intestinal BD. The incidence of spontaneous bowel perforation in patients with Crohn's disease was reported to be 1.5%[3], but the incidence is unclear in patients with BD. Spontaneous bowel perforation in patients with intestinal BD could be single or multiple and is not limited to the ileocecal region[4,5]. Patients can experience severe abdominal pain, abdominal distention, nausea, vomiting, obstipation and fever[2,4-6] and often require surgical intervention[2,4,5,7], such as colonic repair and enterectomy. BD with spontaneous intestinal perforation could be confused with other common acute abdominal diseases, for example, acute suppurative appendicitis, due to the similarities of the abdominal symptoms and signs. An abdominal X-ray or a CT scan before colonoscopy or surgery can facilitate the detection of the occurrence of spontaneous bowel perforation.

It is estimated that the incidence of iatrogenic intestinal perforation is 0.016%-0.8% for diagnostic colonoscopies and 0.02%-8% for therapeutic colonoscopies[8]. Iatrogenic colonoscopic perforation could be detected while performing colonoscopy or after colonoscopy based on early symptoms, such as persistent abdominal pain and distention, or later symptoms and signs, such as fever, leukocytosis and abdominal rebound tenderness as a result of peritonitis[9]. In general, the sigmoid colon is the most common site of perforation (53%-65%)[8]. Due to the existence of ileocecal deep ulcers, patients with intestinal BD are at higher risk of perforation, and the ileocecal area may be the most common site of perforation. Insufflation and biopsy may lead to pressure-related and mechanical injuries of the colonic wall. Therefore, for patients with suspected intestinal BD, careful operation is required for endoscopy. It is necessary to reduce the amount of air insufflation or use carbon dioxide (CO2) insufflation. Biopsies should be taken from the mucosa at the edges of the ulcers. Endoscopists should pay attention to the patient's abdominal signs, especially when performing colonoscopy under general anesthesia.

In this case, bilateral pneumothorax occurred on the basis of intestinal perforation, resulting in shortness of breath and confusion. Both pneumoperitoneum and pneumoretroperitoneum were revealed by a CT scan. Massive air in the retroperitoneal space might leak out of the intestine directly through extraperitoneal intestinal perforation or indirectly through intraperitoneal intestinal perforation[10]. The free air could then extend upward along the esophageal hiatus or aortic hiatus to the mediastinum and pleural space[11], resulting in pneumomediastinum and bilateral pneumothorax. The air could then spread along the muscles and fascia to the loose subcutaneous tissue[12], resulting in subcutaneous emphysema of the neck, chest, abdomen, back and scrotum. Severe intra-abdominal infection did not occur because of bowel preparation. Surgery was not required; therefore, we could not determine the location or number of perforations.

Pneumothorax during or after a routine colonoscopy could appear in patients without underlying bowel diseases, as well as in those with diverticulosis, inflammatory bowel disease, previous colectomy, stricture and fecal impaction[13]. To our knowledge, this is the first report of pneumothorax and subcutaneous emphysema related to bowel perforation in a patient with intestinal BD. In this case, tracheal intubation was impossible due to the patient’s limited mouth opening caused by recurrent oral ulcers, which undoubtedly increased the difficulty of rescue.

Patients with intestinal BD should be fully assessed and adequately prepared before colonoscopy. Endoscopists and anesthesiologists should be aware of the possibility of pneumothorax related to intestinal perforation when a patient’s oxygen saturation drops during a colonoscopy, especially under general anesthesia.

We are grateful to the nurses, anaesthesiologists and thoracic surgeon for their assistance to the rescue.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Mohamed SY, Sintusek P S-Editor: Xing YX L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Hisamatsu T, Naganuma M, Matsuoka K, Kanai T. Diagnosis and management of intestinal Behçet's disease. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2014;7:205-212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Cakal B, Koklu S, Beyazit Y, Ozdemir A, Beyazit F, Ulker A. Fatal colonic perforation in a pregnant with Behçet's disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2011;5:273-274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Greenstein AJ, Sachar DB, Mann D, Lachman P, Heimann T, Aufses AH Jr. Spontaneous free perforation and perforated abscess in 30 patients with Crohn's disease. Ann Surg. 1987;205:72-76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sekmen U, Muftuoglu T, Sagiroglu J, Gungor O. Multiple perforations along the entire colon as a complication of intestinal Behcet's disease: a rare case. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:85-87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kuru S, Demırel AH, Dönmez M. A case of Behçet's disease with multiple colon perforations. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2010;21:324-325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Arhan M, Ibis M, Köklü S, Özin Y, Oymaci E. Behcet’s Disease Complicated with Descending Colon Perforation. Dig Surg. 2005;22:381. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Vicente CS, Freitas AD. Surgical treatment of intestinal perforation in Behçet Syndrome: an unusual presentation. Pan Afr Med J. 2018;30:230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | de'Angelis N, Di Saverio S, Chiara O, Sartelli M, Martínez-Pérez A, Patrizi F, Weber DG, Ansaloni L, Biffl W, Ben-Ishay O, Bala M, Brunetti F, Gaiani F, Abdalla S, Amiot A, Bahouth H, Bianchi G, Casanova D, Coccolini F, Coimbra R, de'Angelis GL, De Simone B, Fraga GP, Genova P, Ivatury R, Kashuk JL, Kirkpatrick AW, Le Baleur Y, Machado F, Machain GM, Maier RV, Chichom-Mefire A, Memeo R, Mesquita C, Salamea Molina JC, Mutignani M, Manzano-Núñez R, Ordoñez C, Peitzman AB, Pereira BM, Picetti E, Pisano M, Puyana JC, Rizoli S, Siddiqui M, Sobhani I, Ten Broek RP, Zorcolo L, Carra MC, Kluger Y, Catena F. 2017 WSES guidelines for the management of iatrogenic colonoscopy perforation. World J Emerg Surg. 2018;13:5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Shi X, Shan Y, Yu E, Fu C, Meng R, Zhang W, Wang H, Liu L, Hao L, Lin M, Xu H, Xu X, Gong H, Lou Z, He H, Xing J, Gao X, Cai B. Lower rate of colonoscopic perforation: 110,785 patients of colonoscopy performed by colorectal surgeons in a large teaching hospital in China. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:2309-2316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Bouma G, van Bodegraven AA, van Waesberghe JH, Mulder CJ, Pieters-van den Bos IC. Post-colonoscopy massive air leakage with full body involvement: an impressive complication with uneventful recovery. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1330-1332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Abdalla S, Gill R, Yusuf GT, Scarpinata R. Anatomical and Radiological Considerations When Colonic Perforation Leads to Subcutaneous Emphysema, Pneumothoraces, Pneumomediastinum, and Mediastinal Shift. Surg J (N Y). 2018;4:e7-e13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ignjatović M, Jović J. Tension pneumothorax, pneumoretroperitoneum, and subcutaneous emphysema after colonoscopic polypectomy: a case report and review of the literature. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2009;394:185-189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Gupta A, Zaidi H, Habib K. Pneumothorax after Colonoscopy - A Review of Literature. Clin Endosc. 2017;50:446-450. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |