Published online Feb 26, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i6.1946

Peer-review started: August 6, 2021

First decision: November 11, 2021

Revised: November 16, 2021

Accepted: January 11, 2022

Article in press: January 11, 2022

Published online: February 26, 2022

Processing time: 201 Days and 8.2 Hours

Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia (COP), formerly known as bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia, is an extremely rare disease in pregnancy. In this case, we report on COP diagnosed in recurrent pneumonia that does not respond to antibiotics in pregnant woman.

A 35-year-old woman with no prior lung disease presented with concerns of chest pain with cough, sputum, dyspnea, and mild fever at 11 wk’ gestation. She was diagnosed with community-acquired pneumonia and treated with antibiotics; her symptoms improved temporarily. Four weeks after discharge, she was re-admitted with aggravated symptoms. Chest computed tomography demonstrated multifocal patchy airspace consolidation and ground-glass opacities at the basal segments of the right lower lobe, at the lateral basal segment of the lower lobe, and at the lingular segment of the left upper lobe. Bronchoalveolar lavage revealed an increased lymphocyte count and a decreased CD4/CD8 ratio. Pred

This case suggests that it is important to differentiate COP from atypical pneumonia in the deteriorated condition despite antibiotic treatment.

Core Tip: Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia (COP) is a diffuse infiltrating lung disease, wherein granulation tissue proliferates in the small bronchiolar epithelium. The COP is an extremely rare in pregnancy. We present the fourth case of COP during pregnancy. This case highlights that it is important to differentiate COP from other types of pneumonia that does not respond and aggravated despite of empirical antibiotics in pregnant woman. The corticosteroid administration is effective in the treatment of COP during pregnancy.

- Citation: Lee YJ, Kim YS. Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia associated with pregnancy: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(6): 1946-1951

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i6/1946.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i6.1946

Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia (COP) is a diffuse infiltrating lung disease, wherein granulation tissue proliferates in the small bronchiolar epithelium damaged owing to various causes and consequently obstructs alveolar ducts and alveoli[1,2]. The occurrence of COP in pregnancy is extremely rare and pregnancy-related physiological changes may worsen respiratory complications in COP. Previously reported cases had pre-onset underlying diseases such as asthma, fungal infection and Crohn's disease that can cause inflammatory condition (Table 1). Here, we report the fourth case of COP in a pregnant woman without underlying medical history initially diagnosed with community-acquired pneumonia that did not improve with antibiotic treatment.

| Case No. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Ref. | Ghidini et al[1], 1999 | Futagami et al[10], 2003 | Holder et al[5], 2011 | Present |

| Age (yr) | 27 | 33 | 16 | 35 |

| Underlying disease | HIV | ITP, asthma | COP, pulmonary hypertension, asthma, partial right lower-lobe resection | None |

| Gestational age (wk) at diagnosis | 26 + 5 | 38 | 20 | 16 + 1 |

| Gestational age (wk) at delivery | 34 | 38 | 28 | 39+4 |

| Symptoms | Cough, dyspnea, chest pain | Cough, fever | Dyspnea, chest pain, fatigue | Chest pain, cough, dyspnea, sputum |

| Radiologic Findings | Diffuse bilateral parenchymal infiltrates (left lower lobe) in chest X-ray | Diffuse bilateral parenchymal infiltrates in chest X-ray | Patchy ground glass infiltrates in chest CT | Multifocal patchy airspace consolidation and GGO |

| Initial diagnosis | Asthmatic bronchitis or interstitial; Pneumonia | Asthmatic bronchitis or mycoplasmic pneumonia | Pre-existing COP | CAP |

| Definite diagnosis method | Open lung biopsy | BAL, TBLB | NA | BAL, TBLB |

| Initial treatment | Trimethoprim (300 mg) + sulfamethoxazole (1500 mg) IV every 6 h + ceftriaxone (2 g) IV daily, methylprednisolone, 60 mg IV every 8 h | Cefmetazole 1 g every 12 h + gabexatemesilate 2 g IV continuously | NA | Ceftriaxone (2 g daily) IV + amoxicillin (250 mg every 8 h), cefpodoxime (100 mg every 12 h) orally |

| Final treatment | Dexamethasone, 5 mg IV every 12 h for 72 h, folowed by methylprednisolone, 60 mg IV daily for 48 h, then 30 mg IV every 8 h for 4 d; and prednisone 40 mg/d orally | Minocycline 100 mg + methylprednisolone 125 mg every 12 h and every 8 h, for 5 d, followed 40 mg per day orally for 11 d | Nebulizer of a beta-2 agonist and corticosteroids | Prednisolone (0.5 mg/kg/d) for 10 d |

A 35-year-old woman, gravida 2, para 1, presented with concerns of chest wall pain with cough, sputum, dyspnea, and mild fever of 37.7 °C at 11 wk of gestation.

The mild cough was started ten days ago with gradually aggravated feature.

Her obstetric history included spontaneous vaginal delivery at 40 wk of gestation, with no special medical history. In particular, there was no history of previous pulmonary diseases.

A 7.5 pack-year history of smoking was noted before the first pregnancy by an antenatal evaluation.

On admission, the patient’s blood pressure was 120/80 mmHg, body temperature was 37.7 °C, pulse rate was 108/min, oxygen saturation was 96%, and respiratory rate was 28/min with a rale in the right lower lung area.

Laboratory tests indicated a white blood cell count of 7.59 × 103/µL (74.9% neutrophils, 10.8% lymphocytes, and 3.5% monocytes) with an absolute neutrophil count of 5680 cells/µL, a hemoglobin level of 12.1 g/dL, a platelet count of 284 × 103/µL, and an elevated C-reactive protein level of 4.77 mg/dL.

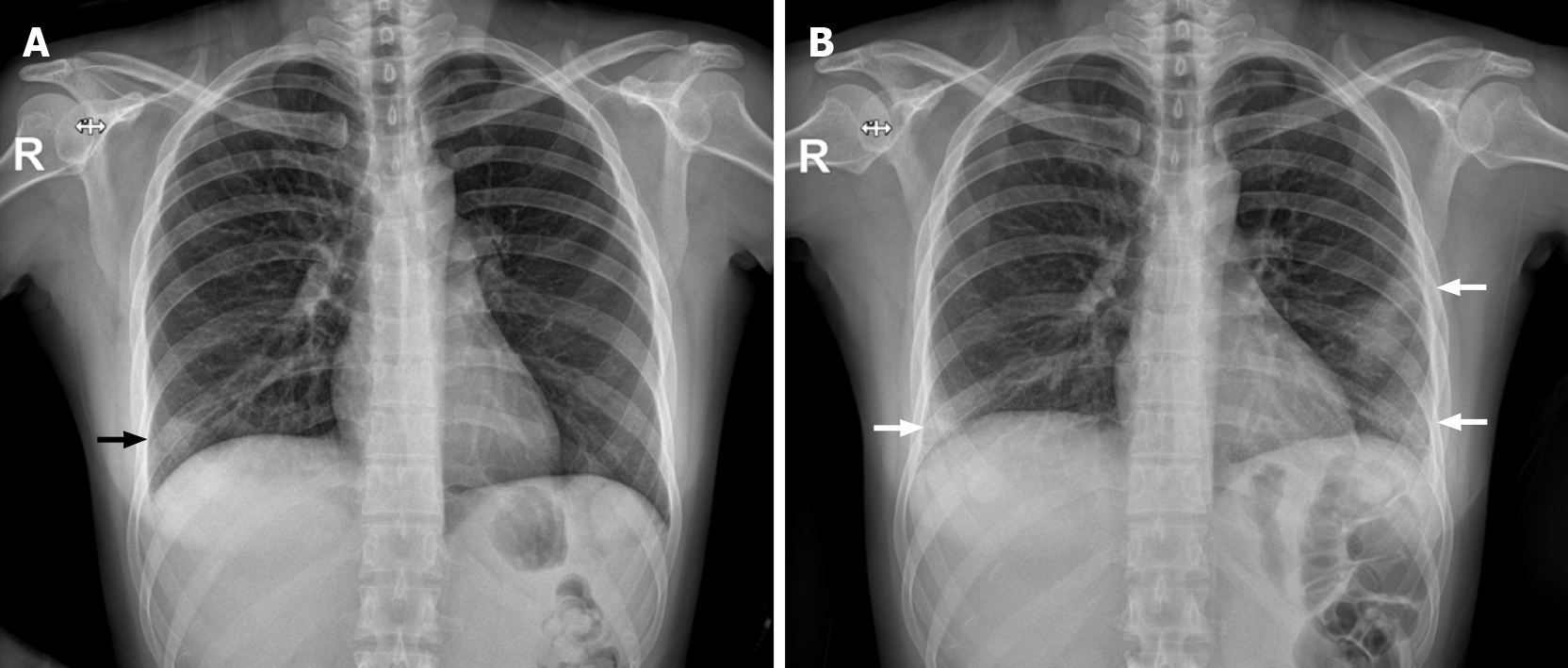

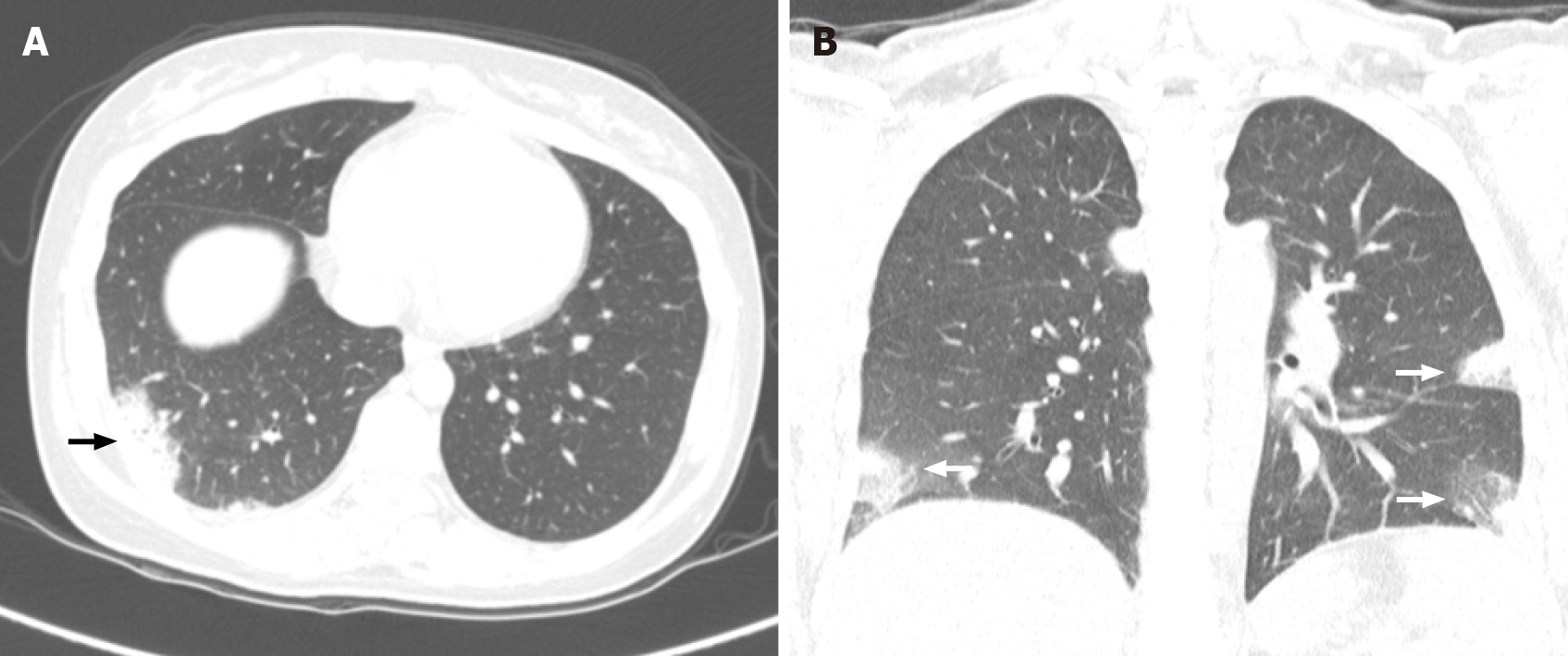

Chest radiography showed increased patchy opacities in the right lower lobe (Figure 1), and computed tomography (CT) revealed some patchy lobular consolidation and peripheral ground-glass opacities (GGOs) in the posterior and lateral basal segments of the right lower lobe (Figure 2). The pulmonary function test showed a forced vital capacity (FVC) of 2.87 L (77% of predicted), forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) of 2.35 L (74% of predicted), FEV/FVC ratio of 82%, and peak expiratory flow of 6.19 L/s. The tidal flow-volume curve revealed minimal obstructive lung disease. An ultrasound examination showed that appropriate fetal growth for the gestational age, a normal amount of amniotic fluid, and no specific abnormal findings.

The increased lymphocyte count (40%) and a decrease in the CD4/CD8 ratio (0.6) with the presence of macrophages (25%) and neutrophils (8%) in BAL suggested a diagnosis of COP.

We began steroid treatment with prednisolone (0.5 mg/kg/d), and progressive improvement of radiological findings was noted. Dyspnea improved after 3 d of steroid treatment, and other symptoms were reduced on the 5th day of steroid administration.

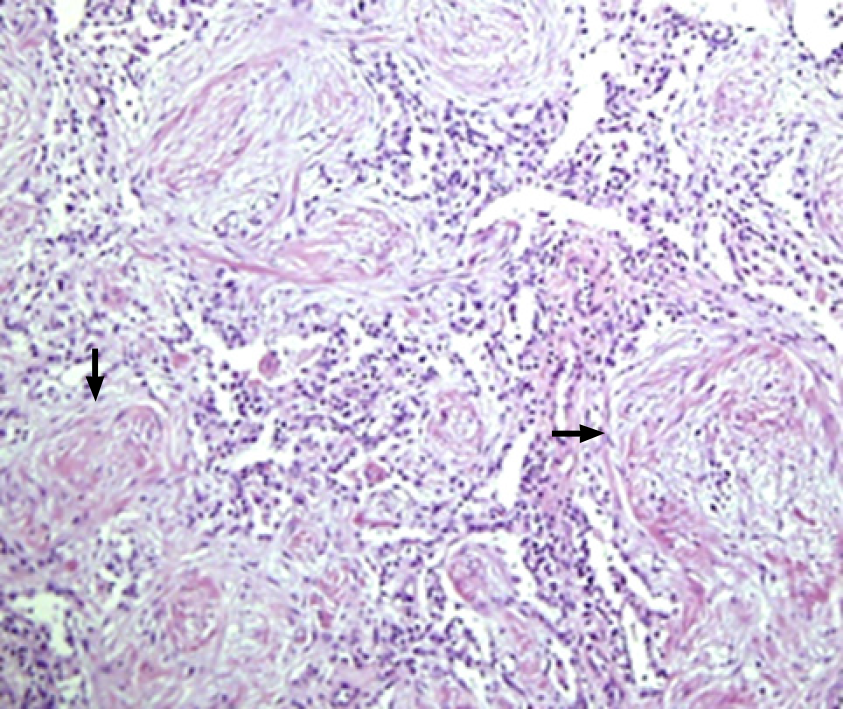

Post-discharge, the patient did not express any special events during pregnancy and gave birth by vaginal delivery at 39+4 d of gestation (male, 3370 g; Apgar scores of 8 and 9 at 1 and 5 min, respectively). Transbronchial lung biopsy was conducted after delivery without any complications, and the proliferation of granulation tissue into the bronchioles and alveolar duct indicated COP (Figure 3).

The prevalence of COP is unknown and is mainly observed in individuals aged 50-60 years[3]. COP occurrence during pregnancy is extremely rare, but it could be more severe owing to physiologic changes in pregnant women, such as an elevated diaphragm, increased oxygen demand, decreased functional residual capacity, and decreased chest wall compliance[4]. Thus, previous reports have recommended close antenatal care and regular pulmonary function tests to reduce respiratory complications during pregnancy; further, elective preterm delivery can be an option in more severe cases[5].

The clinical features of COP in the case described above were not notably different from the general clinical features of COP. The respiratory symptoms began with a flu-like illness with cough, mild fever, malaise and progression of shortened breathing to dyspnea[2]. Although a quarter of patients with COP had no special physical findings[3], inhalation rales or crackling were observed in the physical examination in this case.

In general, imaging approaches are employed to diagnose COP. Chest radiography for COP has three characteristic features: multiple alveolar opacities (typical COP), solitary opacity (focal COP), and infiltrative opacities (infiltrative COP). Bilateral multiple opacities are more common than solitary patterns[6,7]. In our patient, bilateral patchy opacities were observed in both lower lobes. Thin-section CT scans have a correct diagnosis rate of 79% with histologically proved COP[8]. CT findings for COP are patchy GGOs in the subpleural and/or peribronchovascular area (80%), airspace consolidation in bilateral lower lobes (71%), wall thickening and cylindrical dilatation of air bronchogram (71%), ill-defined small nodular opacities (50%), and pleural effusion (in a third of patients)[9]. The specific multifocal patchy airspace consolidation, GGOs, and bilateral pleural effusion were observed.

Corticosteroids are administered as the initial treatment for COP and are effective for both typical and focal COP. The recommended treatment regimens include initial dosages of 0.75-1.5 mg/kg prednisolone for 3 mo with gradual reduction according to clinical symptom improvement[10]. In this case, we began with a low initial oral dose of prednisolone of 0.5 mg/kg/d after the patient’s second admission because corticosteroid use in first trimester can be associated with the development of an orofacial cleft. Fortunately, symptoms improved after 5 d of the low-dose administration and maintenance therapy was continued for 5 more days. This rare case is about the COP diagnosed in pregnant women without underlying medical conditions. In addition, it suggests a diagnostic value of COP, which is less effective in conevntional initial treatment. In this case, a pregnant woman was initially diagnosed with community-acquired pneumonia and treated with antibiotics; her symptoms seemed to improve temporarily but then recurred with greater severity.

COP has similar clinical features with other types of pneumonia and in particular, chest radiographic differentiation of COP could be difficult. The progressive condition indicates a specific clinical aspect of COP; thus, it is important to differentiate COP from other atypical pneumonia that recur despite initial antibiotic treatment.

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Respiratory System

Country/Territory of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Barbosa OA, He Z, Wen XL S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Ghidini A, Mariani E, Patregnani C, Marinetti E. Bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;94:843. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Cordier JF. Cryptogenic organising pneumonia. Eur Respir J. 2006;28:422-446. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 337] [Cited by in RCA: 315] [Article Influence: 16.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Epler GR, Colby TV, McLoud TC, Carrington CB, Gaensler EA. Bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:152-158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 663] [Cited by in RCA: 587] [Article Influence: 14.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Mehta N, Chen K, Hardy E, Powrie R. Respiratory disease in pregnancy. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2015;29:598-611. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Holder KL, Scardo JA, Laye MR. Elective preterm delivery as a management option in cryptogenic organizing pneumonia. Obstet Med. 2011;4:76-79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Cordier JF, Loire R, Brune J. Idiopathic bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia. Definition of characteristic clinical profiles in a series of 16 patients. Chest. 1989;96:999-1004. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 207] [Cited by in RCA: 182] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Flowers JR, Clunie G, Burke M, Constant O. Bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia: the clinical and radiological features of seven cases and a review of the literature. Clin Radiol. 1992;45:371-377. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Johkoh T, Müller NL, Cartier Y, Kavanagh PV, Hartman TE, Akira M, Ichikado K, Ando M, Nakamura H. Idiopathic interstitial pneumonias: diagnostic accuracy of thin-section CT in 129 patients. Radiology. 1999;211:555-560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 260] [Cited by in RCA: 222] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Al-Ghanem S, Al-Jahdali H, Bamefleh H, Khan AN. Bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia: pathogenesis, clinical features, imaging and therapy review. Ann Thorac Med. 2008;3:67-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Futagami M, Sakamoto T, Sakamoto A, Shigetou T, Taniguchi R, Fukuhara R. Bronchiolitis obliterans organising pneumonia in pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2003;23:309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |