Published online Feb 26, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i6.1876

Peer-review started: July 5, 2021

First decision: October 11, 2021

Revised: October 22, 2021

Accepted: January 19, 2022

Article in press: January 19, 2022

Published online: February 26, 2022

Processing time: 233 Days and 11.8 Hours

Acute portal vein thrombosis (PVT) with bowel necrosis is a fatal condition with a 50%-75% mortality rate. This report describes the successful endovascular treatment (EVT) of two patients with severe PVT.

The first patient was a 22-year-old man who presented with abdominal pain lasting 3 d. The second patient was a 48-year-old man who presented with acute abdominal pain. Following contrast-enhanced computed tomography, both patients were diagnosed with massive PVT extending to the splenic and superior mesenteric veins. Hybrid treatment (simultaneous necrotic bowel resection and EVT) was performed in a hybrid operating room (OR). EVTs, including aspiration thrombectomy, catheter-directed thrombolysis (CDT), and continuous CDT, were performed via the ileocolic vein under laparotomy. The portal veins were patent 4 and 6 mo posttreatment in the 22-year-old and 48-year-old patients, respectively.

Hybrid necrotic bowel resection and transileocolic EVT performed in a hybrid OR is effective and safe.

Core Tip: Acute portal vein thrombosis (PVT) with bowel necrosis is a fatal condition with no definite cure. This report describes successful endovascular treatment (EVT) in two severe PVT cases. Hybrid treatment (simultaneous necrotic bowel resection and EVT) was performed in a hybrid operating room. EVTs, including aspiration thrombectomy, catheter-directed thrombolysis (CDT), and continuous CDT, were performed via the ileocolic vein under laparotomy. By performing this procedure, we were able to achieve a good result for a disease with a low survival rate and did so with minimal intestinal resection.

- Citation: Shirai S, Ueda T, Sugihara F, Yasui D, Saito H, Furuki H, Kim S, Yoshida H, Yokobori S, Hayashi H, Kumita SI. Transileocolic endovascular treatment by a hybrid approach for severe acute portal vein thrombosis with bowel necrosis: Two case reports. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(6): 1876-1882

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i6/1876.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i6.1876

Acute portal vein thrombosis (PVT) is a rare condition involving thrombus formation in the portal vein (PV) and its branches. Extension of the thrombus to the splenic vein (SV) and superior mesenteric vein (SMV) may lead to bowel necrosis, which has a reported mortality rate of 50%-75%[1-3]. Although systemic anticoagulation is the standard treatment for PVT, most thrombi (both intra- and extrahepatic) are not sufficiently dissolved using this therapeutic approach[4,5]. Recently, in addition to systemic anticoagulation, endovascular treatments (EVTs), including aspiration thrombectomy (AT) and catheter-directed thrombolysis (CDT), have been reported to be useful for PVT[6]. However, they have yet to be established as recommended treatment strategies for this condition. Additionally, in previous reports of EVT used for PVT, transjugular, transhepatic, or transsplenic approaches to the PV are relatively common, whereas the transileocolic approach under laparotomy is rarely reported[7]. Hybrid treatment [performed in a hybrid operating room (OR)], which consists of simultaneous surgical necrotic bowel resection and thrombus removal by transi

Case 1: A 22-year-old man presented with abdominal pain lasting 3 d.

Case 2: A 48-year-old man presented with acute abdominal pain lasting 1 wk.

Case 1: This man had abdominal pain and visited another hospital but was diagnosed with gastroenteritis and returned home. After that, his symptoms worsened, and he was taken to the emergency room again. He was diagnosed with gastroenteritis by computed tomography and was hospitalized. Melena was observed at night on the same day, and intestinal ischemia was suspected based on contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT).

Case 2: This man was admitted to another hospital because of epigastric pain. He was diagnosed with reflux esophagitis and was prescribed an analgesic. He returned home and was followed up. Afterwards, the patient’s abdominal pain and nausea worsened, and he again went to his local hospital. He was referred to our hospital on suspicion of acute peritonitis.

Case 1: The patient had a history of acute pancreatitis.

Case 2: There was no significant past illness.

There was no significant personal or family history in two patients.

Case 1: The abdomen had diffuse tenderness, with rebound tenderness in the entire area.

Case 2: The abdomen had diffuse distention and tenderness, with rebound tenderness in the entire area.

Case 1: Blood test results were as follows: white blood cell count, 17.7 × 10³/μL; neutrophil count, 86.0%; C-reactive protein (CRP), 9.03 mg/dL; aspartate aminotransferase, 499 U/L; alanine aminotransferase, 575 U/L; creatinine phosphokinase, 2888 U/L; lactate dehydrogenase, 1025 U/L; and lactate, 19 mg/dL.

Case 2: Blood test results were as follows: white blood cell, 18.5 × 10³/μL and CRP, 20.56 mg/dL. Liver function and lactate analyses revealed no abnormal changes.

Case 1: CECT showed massive PVT extending to the SV and SMV with non

Case 2: CECT showed complete PVT extending to the SMV and SV without contrast medium enhancement in the jejunum walls. The wall of the small intestine was edematous and thickened, and the contrast effect was also diminished. The intestinal wall was edematous and thickened, accompanied by a large amount of ascites.

The patient’s condition was diagnosed as acute PVT extending to the splenic and SMVs with bowel necrosis.

The patient’s condition was diagnosed as severe PVT extending to the splenic and SMVs with bowel necrosis.

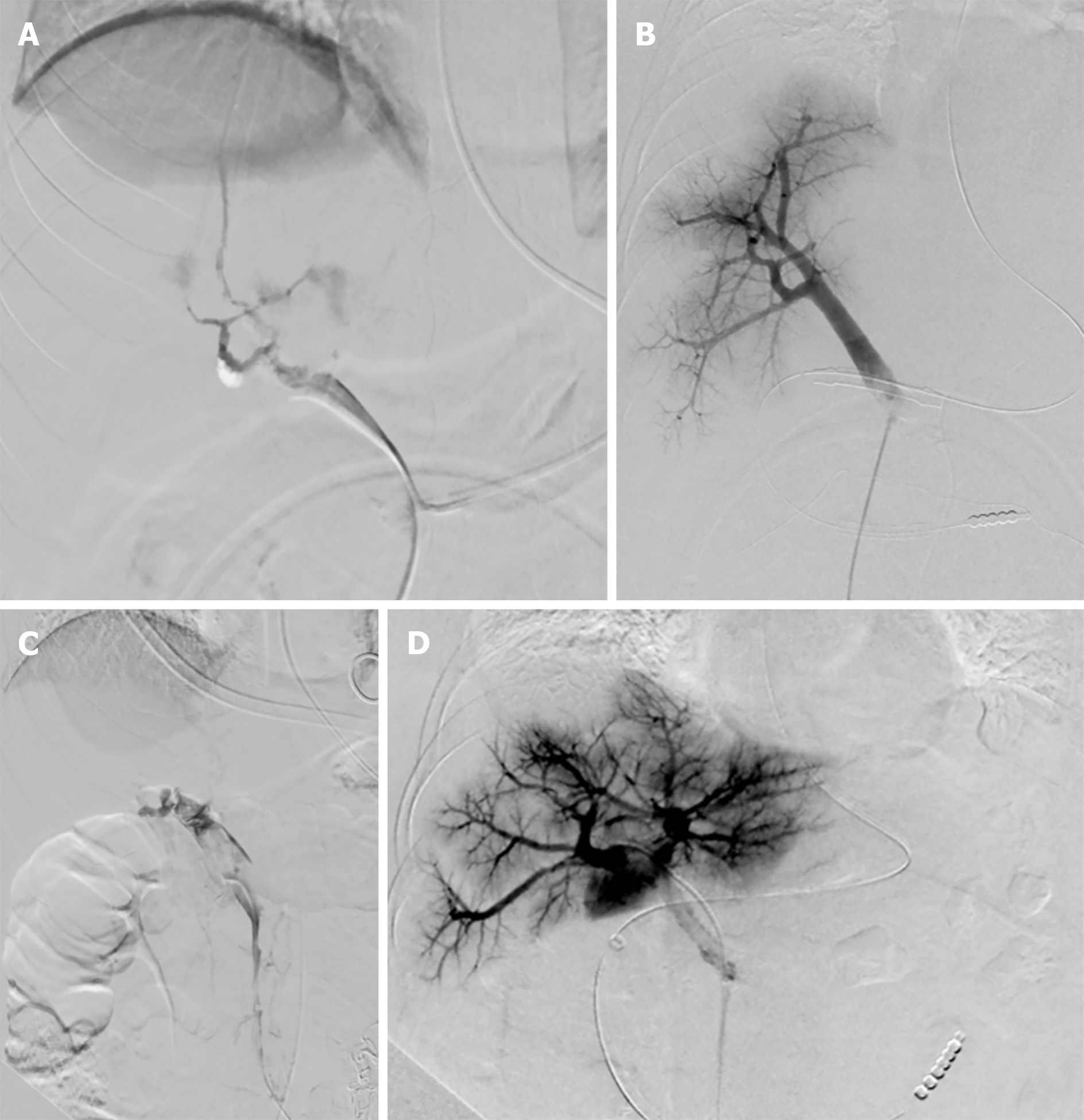

A decision was made to perform an emergency hybrid treatment including simultaneous surgical necrotic bowel resection and EVT in a hybrid OR. Under general anesthesia, approximately 340 cm of necrotic bowel, which appeared as irreversible bowel ischemia at the time of laparotomy, was resected from the region between the distal ileum and the proximal jejunum. EVT via the ileocolic vein was performed immediately after the surgery (Figure 1A) over three sessions within a period of 4 d. The blood flow from the main PV to the right PV was completely recovered by the end of the final EVT (Figure 1B).

Hybrid treatment was performed in a hybrid OR with the patient under general anesthesia over a total of four sessions of EVT. In the first session, considering that bowel ischemia could be improved by EVT, open abdomen management without resection was adopted. However, the next day, there was no improvement in the ischemic bowel, indicating that the change was irreversible. In the subsequent session, approximately 210 cm of necrotic bowel was resected in total, and the thrombus was removed using the same method as that used in case 1 (Figure 1C). A total of four EVT sessions took place over a period of 5 d. The final angiogram showed good PV flow at the end of the fourth EVT session (Figure 1D).

During the laparotomy, the ileocolic vein was divided, isolated, and punctured with an 18-G needle (Catheter Introducer; Medikit, Tokyo, Japan). After ligation of the proximal end of the ileocolic vein, a 0.035-in guidewire (Radifocus Guide Wire M; Terumo, Tokyo, Japan) was inserted, and an 8-Fr sheath (Supersheath; Medikit) was inserted. At this point, heparin (5000 U) was administered. A further 1000 U was then administered every hour to keep the activated clotting time within the range of 200-300 s. Next, the 0.035-in guidewire and a 4-Fr guide catheter (GLIDECATH; Terumo) were advanced into the PV, SMV, and SV via the sheath. The 4-Fr guide catheter was then replaced with a 6-Fr catheter (Aspiraircass; Medikit) and an 8-Fr guiding catheter (Launcher; Medtronic, Dublin, Ireland) for the patient in case 1 and the patient in case 2, respectively. Manual AT using these catheters was repeatedly performed. Additionally, to remove the residual thrombus found after AT, CDT using 30000 U of urokinase (Mochida, Tokyo, Japan) for the patient in case 1 and 24000 U for the patient in case 2 was performed via a 5-Fr multiple-side-hole infusion catheter (Fountain Infusion System; Merit Medical, South Jordan, UT) within the same session. This was repeated almost every day for 3 d in the patient in case 1 and for 4 d in the patient in case 2 until peripheral PV circulation was completely restored. During the interval between each session, a 5-Fr sheath (Medikit) and a heparin-coated catheter (Anthron; Toray Medical, Tokyo, Japan) were kept in place within the SMV and PV. Continuous CDT using urokinase was performed via the sheath (120000 U/d) and catheter (240000 U/d) with an open abdomen and continuous negative pressure.

After the treatments, an intravenous injection of systemic heparin (20000-50000 U; Mochida) was administered daily for 45 d, while the activated partial thromboplastin time was maintained at 50-60 s. Heparin was switched to warfarin (Eisai, Tokyo, Japan) 3 mg/d on postfinal EVT Day 40. Although the patient experienced short bowel syndrome, he was discharged 4 mo after the treatment. CECT showed that the patient’s main and right PVs were patent 4 mo after the treatment.

Heparin (15000 U) was replaced with edoxaban (Daiichi-Sankyo, Tokyo, Japan) 60 mg/d on postfinal EVT Day 24. The patient was discharged 33 d after the final EVT. CECT showed that the PV was patent 9 mo after the treatment.

PVT is a rare condition, with an incidence of approximately 0.7 per 100000 people per year[1]. Acute PVT is even more infrequent and is difficult to diagnose. In this case report, acute PVT was diagnosed as gastroenteritis in one patient and peritonitis in another patient. Thus, infections might have induced three factors of Virchow's triad, including intravascular vessel wall damage, stasis of flow, and the presence of a hypercoagulable state, and caused PVT[4]. Focusing on risk factors, such as thrombophilia and portal hypertension, may be effective for diagnosing PVT; however, it is difficult to distinguish PVT from enteritis and other ischemic intestinal diseases, such as arterial thrombosis or nonocclusive mesenteric ischemia, based on clinical symptoms without imaging evaluation[4].

Nevertheless, early diagnosis is important because PVT can be quite severe and is associated with a high mortality rate[1-3]. In severe PVT, such as in these cases, venous congestion is initially induced owing to various etiologies. Hemorrhagic infarction then occurs, and arteriovenous obstruction finally leads to bowel necrosis. Yerdel et al[8] classified PVT into four grades of severity (1 to 4), with Grade 4 being the most severe stage, defined as “complete PV and entire SMV thrombosis.” According to their study, the in-hospital mortality of Grade 4 PVT was 50%. In the present case report, both patients had Grade 4 PVT; nonetheless, despite the severity of their conditions and the high associated mortality rate, positive outcomes were achieved using hybrid treatment including necrotic bowel resection and multiple EVT sessions for thrombi until the intrahepatic blood flow became stable.

Although there are no reports that clearly define the treatment endpoint for PVT, we believe that it is important to improve the inflow and outflow systems of the liver. Sharma et al[4] revealed that different treatments were shown according to the etiologies. It is reasonable to monitor conservatively, without anticoagulation, for reversible risk factors such as pancreatitis or abdominal infections in patients with minimal thrombus in PV. In cases of noncirrhotic, nonmalignant, and symptomatic PVT, anticoagulation is recommended. For asymptomatic PVT, especially with extension to the mesenteric veins, nonreversible risk factors, and hypercoagulable states, anticoagulation is reasonable for preventing or reducing symptoms such as abdominal pain, nausea or vomiting, or ischemic complications, including bowel necrosis and portal hypertension-related symptoms. In patients with PVT accompanied by malignancy, anticoagulation is also recommended in the majority of cases. Thrombolysis can be considered in those with thrombus extension or worsening pain while on anticoagulation and in patients with impending or ongoing bowel necrosis owing to thrombosis. For these, anticoagulation is often recommended.

According to the guidelines for PVT treatment[9], systemic anticoagulation is considered the first-line therapy for this condition. However, collective data from retrospective studies show that anticoagulation alone might be insufficient. A report showed that in cases of extensive PVT in which anticoagulation was initiated early and maintained for 6 mo, 50% of patients recanalized completely, 40% did so partially, and 10% did not recanalize at all[6]. This result supports the idea that combining systemic anticoagulation with EVT might be beneficial, especially in cases of imminent bowel infarction. Furthermore, EVT may become the sole effective therapy for PVT in patients with a contraindication to anticoagulation.

Recently, several EVT techniques, including CDT and AT, have been described for acute PVT[6]. Wang et al[10] reported the successful treatment of 12 patients with acute PVT by aspiration combined with CDT. Eight patients achieved complete recanalization, and four patients achieved partial recanalization, which shows that AT combined with CDT was more effective than monotherapy. Kennoki et al[7] reported a case of successful recanalization of acute extensive PVT by AT and continuous CDT. The present case report involved EVTs, including AT, CDT, and continuous CDT. Although CDT is effective for acute thrombosis and enhances the efficacy of thrombolytics, it generally takes time and may cause clot migration and hemorrhagic complications[11]. In contrast, high recanalization rates have been achieved using AT, which has frequently allowed for the removal of large sections of thrombus all at once. This reduces the time required for recanalization, is not associated with hemorrhagic risk, and may prevent distal embolization, which is not the case in CDT[11]. Nevertheless, a large sheath is generally required to avoid vessel injury, and this cannot be applied to tortuous vessels.

In terms of the approach to the PV, the percutaneous transhepatic, percutaneous transsplenic, and transjugular approaches, including transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS), are known, along with the transileocolic approach under laparotomy. The percutaneous approach is the least invasive. However, it may increase the risk of bleeding. In one report, out of 46 patients who underwent the percutaneous transsplenic approach, 3 (6.5%) had severe bleeding, and 6 (13%) had mild bleeding[7]. Moreover, although TIPS using covered stents is a common procedure in Europe and the United States when approaching the PV, TIPS has not been allowed by the health insurance system in Japan and is only performed in a limited number of institutions. In the present cases, there were a few reasons for the choice of the transileocolic approach. First, the percutaneous approach would have been difficult to perform because of the large amount of ascites, especially in case 1, and the complete occlusion of the intrahepatic PV. Second, considering that both patients required necrotic bowel resection, it was reasonable to perform EVT under laparotomy. Third, the transileocolic approach is associated with a low risk of bleeding compared with other approaches because the ileocolic vein is punctured under direct observation[12]. Finally, this approach enables the use of larger devices for AT. Therefore, the transileocolic approach is considered a useful method that does not cause serious complications in the short term; however, further research and evaluation of the complications and long-term prognosis of patients is required.

As shown in the present cases, surgery and EVT should be performed in a hybrid OR to optimize the treatment of PVT with bowel necrosis. Indeed, the hybrid OR enabled us to reduce the transfer time from the intervention room to the OR and, consequently, the risks related to this transfer. Moreover, these patients’ abdomens were left open with negative pressure applied during the intervals between EVT sessions. The open abdomen allowed for the bowel condition to be monitored and permitted a sheath to be left with a catheter in the PV during the intervals between EVT sessions. Multiple EVT procedures in combination with an open abdomen enabled us to perform minimal bowel resection while visually observing the condition of the bowel.

Herein, two patients with severe acute PVT extending to the SV and SMV with bowel necrosis were successfully treated with EVTs. Overall, hybrid necrotic bowel resection and transileocolic EVT with AT and CDT performed in a hybrid OR were found to be effective and safe.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Japan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Ciccone MM, Dietrich CF, Ennab RM S-Editor: Li X L-Editor: A P-Editor: Li X

| 1. | Rajani R, Björnsson E, Bergquist A, Danielsson A, Gustavsson A, Grip O, Melin T, Sangfelt P, Wallerstedt S, Almer S. The epidemiology and clinical features of portal vein thrombosis: a multicentre study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:1154-1162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Jung HJ, Lee SS. Combination of surgical thrombectomy and direct thrombolysis in acute abdomen with portal and superior mesenteric vein thrombosis. Vasc Specialist Int. 2014;30:155-158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Wolter K, Decker G, Kuetting D, Trebicka J, Manekeller S, Meyer C, Schild H, Thomas D. Interventional treatment of acute portal vein thrombosis. Rofo. 2018;190:740-746. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sharma AM, Zhu D, Henry Z. Portal vein thrombosis: When to treat and how? Vasc Med. 2016;21:61-69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Loffredo L, Pastori D, Farcomeni A, Violi F. Effects of anticoagulants in patients with cirrhosis and portal vein thrombosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2017;153:480-487.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 233] [Cited by in RCA: 297] [Article Influence: 37.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Seedial SM, Mouli SK, Desai KR. Acute portal vein thrombosis: current trends in medical and endovascular management. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2018;35:198-202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kennoki N, Saguchi T, Sano T, Moriya T, Shirota N, Otaka J, Suzuki K, Tomita K, Chiba N, Kawachi S, Koizumi K, Tokuuye K. Successful recanalization of acute extensive portal vein thrombosis by aspiration thrombectomy and thrombolysis via an operatively placed mesenteric catheter: a case report. BJR Case Rep. 2018;4:20180024. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Yerdel MA, Gunson B, Mirza D, Karayalçin K, Olliff S, Buckels J, Mayer D, McMaster P, Pirenne J. Portal vein thrombosis in adults undergoing liver transplantation: risk factors, screening, management, and outcome. Transplantation. 2000;69:1873-1881. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 485] [Cited by in RCA: 525] [Article Influence: 21.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Wu M, Schuster M, Tadros M. Update on management of portal vein thrombosis and the role of novel anticoagulants. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2019;7:154-164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Wang MQ, Liu FY, Duan F, Wang ZJ, Song P, Fan QS. Acute symptomatic mesenteric venous thrombosis: treatment by catheter-directed thrombolysis with transjugular intrahepatic route. Abdom Imaging. 2011;36:390-398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ueda T, Murata S, Miki I, Yasui D, Sugihara F, Tajima H, Morota T, Kumita SI. Endovascular treatment strategy using catheter-directed thrombolysis, percutaneous aspiration thromboembolectomy, and angioplasty for acute upper limb ischemia. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2017;40:978-986. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Yoshida H, Makino H, Yokohama T, Maruyama H, Hirakata A, Ueda J, Takata H, Mamada Y, Taniai N, Uchida E. Interventional radiology: Percutaneous transhepatic obliteration and transileocolic obliteration. In: Obara K, editor. Clinical investigation of portal hypertension. Singapore: Springer, 2019; 403-408. |