Published online Feb 6, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i4.1423

Peer-review started: September 5, 2021

First decision: October 22, 2021

Revised: November 3, 2021

Accepted: December 23, 2021

Article in press: December 23, 2021

Published online: February 6, 2022

Processing time: 141 Days and 5.8 Hours

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is a rare proliferative histiocyte disorder. It can affect any organ or system, especially the bone, skin, lung, and central nervous system (CNS). In the CNS, the hypothalamic-pituitary is predominantly affected, whereas the brain parenchyma is rarely affected. LCH occurring in the brain parenchyma can be easily confused with glioblastoma or brain metastases. Thus, multimodal imaging is useful for the differential diagnosis of these intracerebral lesions and detection of lesions in the other organs.

A 47-year-old man presented with a headache for one week and sudden syncope. Brain computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging showed an irregularly shaped nodule with heterogeneous enhancement. On 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) positron emission tomography/CT, a nodule with 18F-FDG uptake and multiple cysts in the upper lobes of both lungs were noted, which was also confirmed by high-resolution CT. Thus, the patient underwent surgical resection of the brain lesion for further examination. Postoperative pathology confirmed LCH. The patient received chemotherapy after surgery. No recurrence was observed in the brain at the 12-mo follow-up.

Multimodal imaging is useful for evaluating the systemic condition of LCH, developing treatment plans, and designing post-treatment strategies.

Core Tip: Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is a rare hematological disease characterized by a clonal proliferation of abnormal langerhans cells. It can affect any organ or system, especially the bone, skin, lung, and central nervous system (CNS). In the CNS, the hypothalamic-pituitary is predominantly affected, whereas the brain parenchyma is rarely affected. Cases of LCH involving the brain parenchyma and presenting as an isolated brain tumour have been reported, but all the reports lack complete multimodal imaging. In this manuscript, we have reported a case of LCH involving the brain parenchyma and bilateral lungs, which was assessed using computed tomography (CT), high-resolution CT, magnetic resonance imaging, and 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/CT. Furthermore, we have reviewed the relevant literature.

- Citation: Liang HX, Yang YL, Zhang Q, Xie Z, Liu ET, Wang SX. Langerhans cell histiocytosis presenting as an isolated brain tumour: A case report . World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(4): 1423-1431

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i4/1423.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i4.1423

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is an uncommon disease characterized by clonal proliferation of myeloid precursors that differentiate into cluster of differentiation (CD)1a+/CD207+ (Langerin) cells in lesions[1,2]. It mainly affects children, with a reported incidence of 4-5 cases per million children aged < 15 years per year, while its incidence in adults is uncertain[3]. LCH may affect any organ or system, but it most frequently affects the bone, skin, pituitary, liver, spleen, hematopoietic system, lung, lymph nodes, and central nervous system (CNS)[4,5]. Cases of LCH involving the brain parenchyma and presenting as an isolated brain tumour have been reported, but all the reports lack complete multimodal imaging. Herein, we have reported a case of LCH involving the brain parenchyma and bilateral lungs, which was assessed using computed tomography (CT), high-resolution CT (HRCT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) positron emission tomography (PET)/CT. Furthermore, we have reviewed the relevant literature.

A 47-year-old man was referred to our hospital with a headache for one week and sudden syncope in the morning.

A 47-year-old man was referred to our hospital with a headache for one week and sudden syncope in the morning.

The patient had no history of polyuria or polydipsia. No other illnesses were observed.

The patient had no known comorbidities or family history, but had a 15-year smoking history.

No rash or positive neurological signs were found on physical examination.

Laboratory tests results showed increased in carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) levels (7.03 ng/mL, reference: 0-5 ng/mL), with no other abnormal findings.

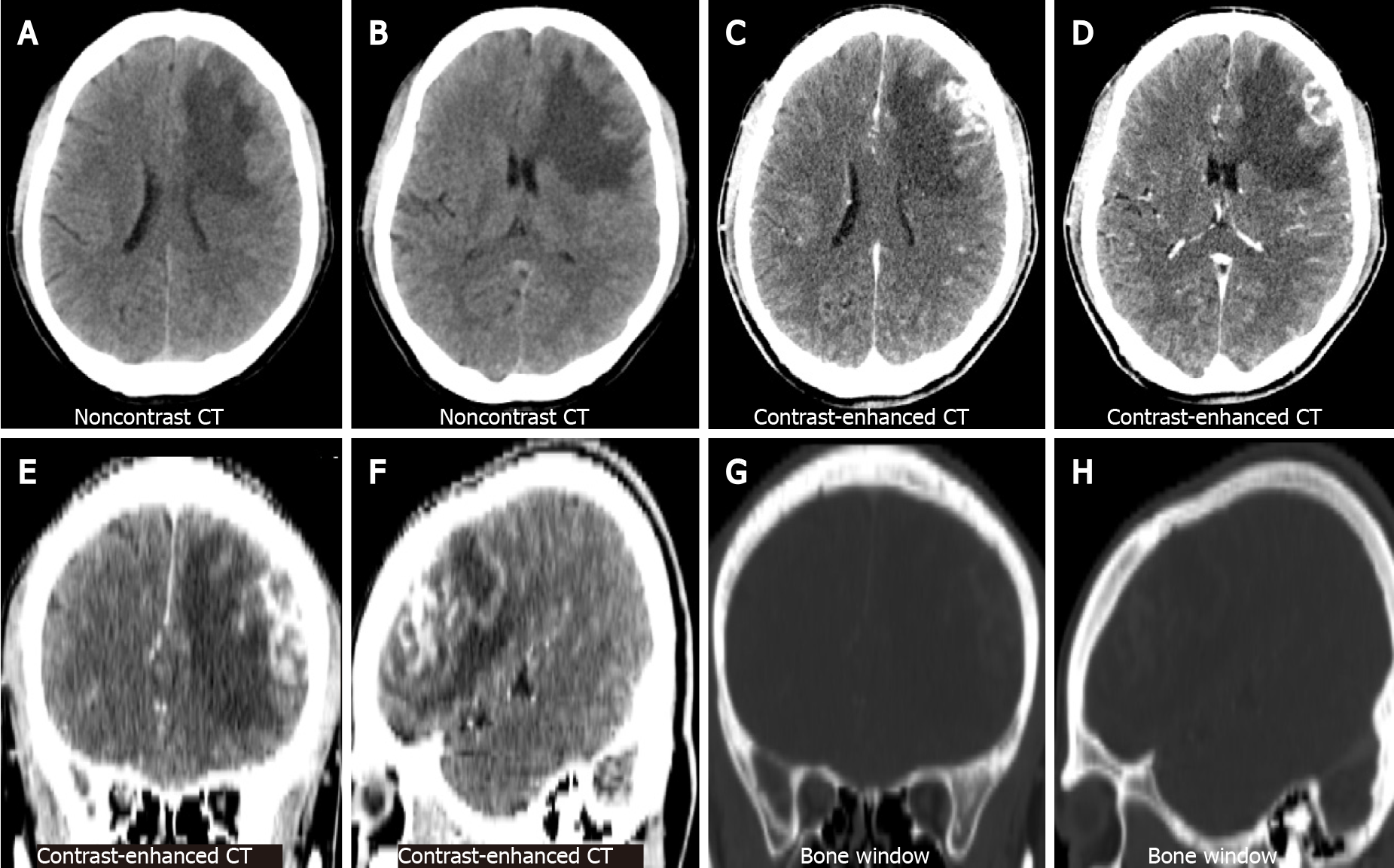

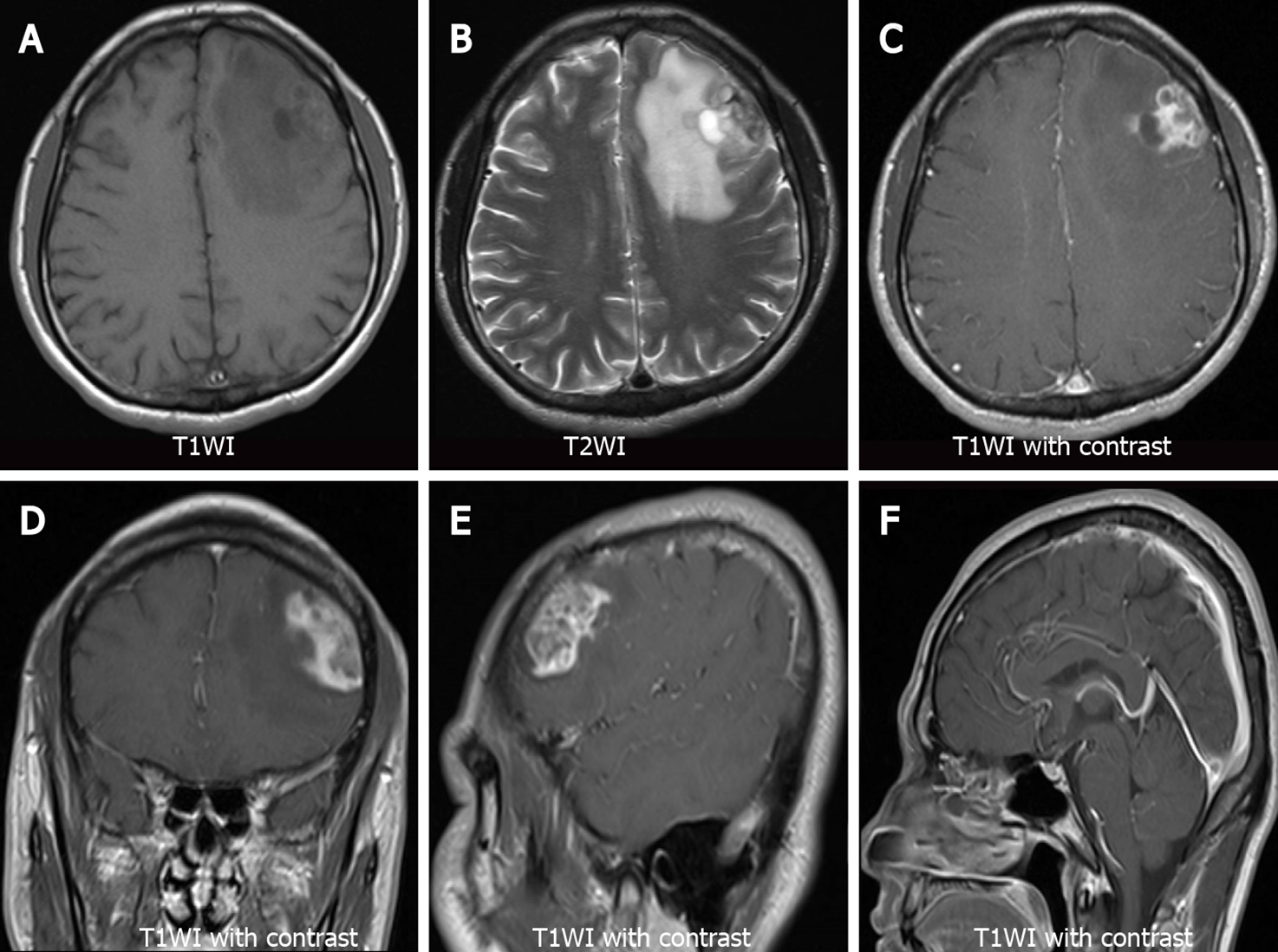

Non-contrast brain CT showed irregularly shaped nodular foci with isodensity at the left frontal corticomedullary junction. Large patches of hypodense edema were noted in the adjacent white matter (Figure 1A and B represent the lateral ventricular and basal ganglia levels, respectively). Contrast-enhanced brain CT showed significant heterogeneous enhancement in the left frontal foci (Figure 1C and D, the same level as the Figure 1A and B). Coronal and sagittal views of contrast-enhanced CT images showed irregular morphology of the lesion and poor demarcation with the adjacent skull (Figure 1E and F). Bone window CT showed no abnormalities in the adjacent skull (Figure 1G and H, the same level as the Figure 1E and F). Subsequently, the patient underwent a brain MRI. Axial T1-weighted images (T1WI) showed heterogeneous hypointense lesions in the left frontal lobe (Figure 2A). Axial T2-weighted images (T2WI) showed a heterogeneously mixed hyperintensity signals with hypointense areas in the left frontal lobe lesion (Figure 2B). After administration of gadolinium, the lesion showed heterogeneous enhancement on axial (Figure 2C), coronal (Figure 2D), and sagittal T1WI (Figure 2E). No abnormalities were found on sagittal T1WI of the sellar region (Figure 2F).

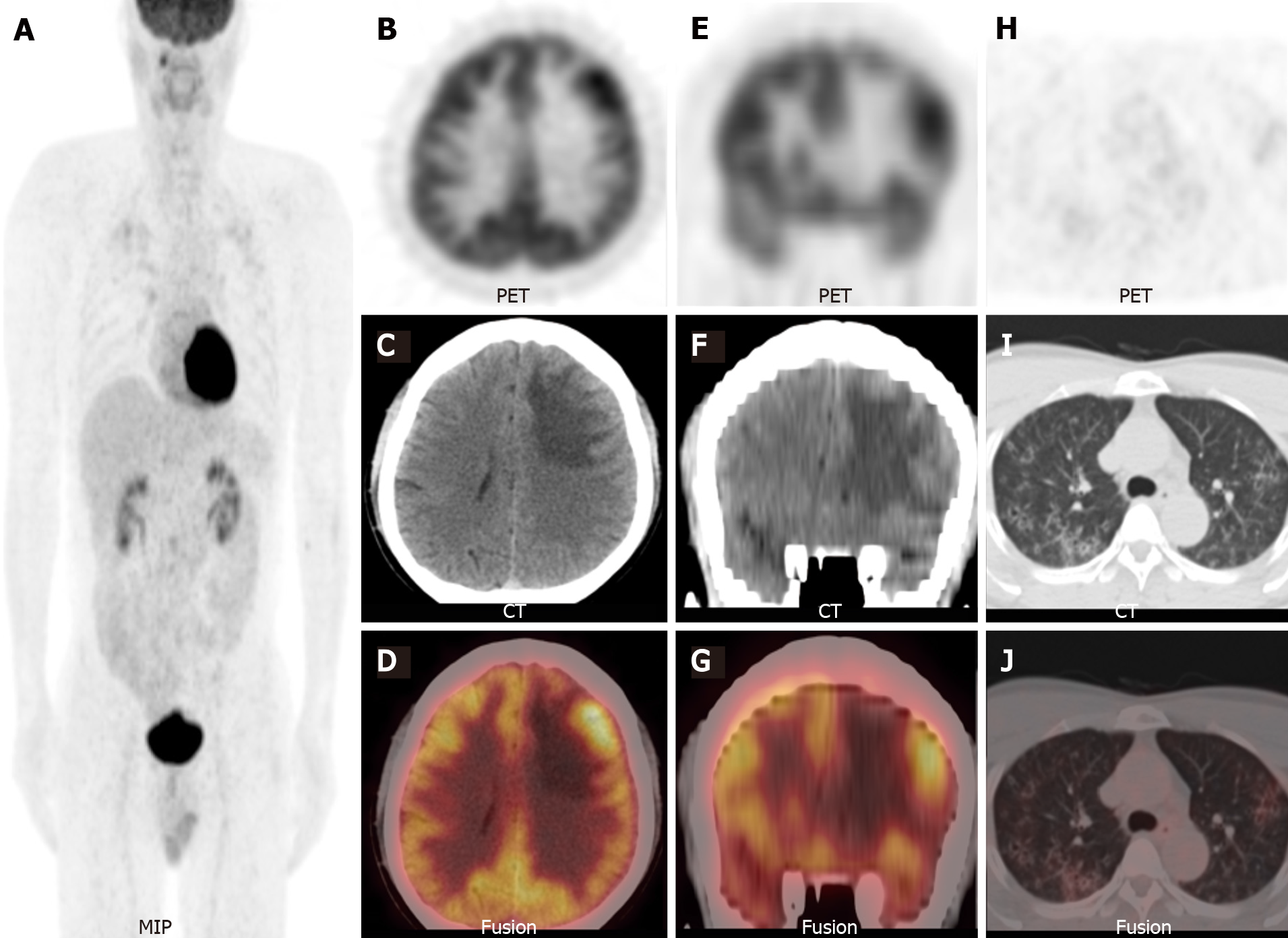

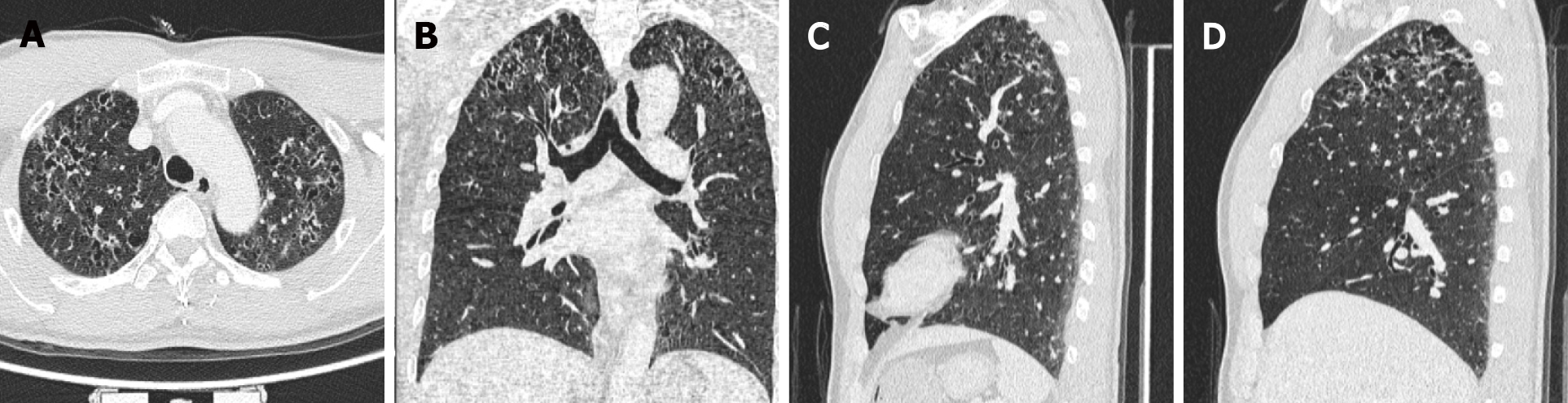

Considering the elevated CEA levels and CT and MRI manifestations, further investigation was required to rule out brain metastases. Therefore, 18F-FDG PET/CT was performed. Maximum-intensity-projection imaging showed a focal increase in 18F-FDG uptake in the right maxillary sinus and multiple foci of increased 18F-FDG uptake in the bilateral lung fields (Figure 3A). Axial (Figure 3B-D) and coronal (Figure 3E-G) views of the selected PET, non-enhanced CT (NE-CT), and fused PET/CT images showed moderately increased 18F-FDG uptake in the left frontal nodule [the maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax) of the lesions and surrounding tissues are shown in Supplementary Figure 1]. No abnormal 18F-FDG uptake was observed in the sellar region (Supplementary Figure 2). Axial (Figure 3H-J) views of the selected PET, NE-CT, and fused PET/CT images showed multiple cysts with peripheral exudation in the upper lobes of bilateral lungs, with slightly increased 18F-FDG uptake. HRCT was performed to further evaluate the pulmonary lesions. Axial (Figure 4A), coronal (Figure 4B), and sagittal (Figure 4C and D, left and right lungs, respectively) views of HRCT images showed multiple scattered small thick-walled irregular cysts and small nodules. Sinusitis was diagnosed in the right maxillary sinus. Bilateral lung manifestations should be differentiated from pulmonary LCH, but brain nodules are more difficult to diagnose and should be differentiated from gliomas.

The patient underwent brain tumour resection. Gross examination showed that the specimen was a grey-brown solid tumour (Figure 5A) and the cut surface was grey-brown and grey-white (Figure 5B). Histopathological examination revealed mononucleated and multinucleated histocytes with abundant cytoplasm and slight staining (haematoxylin and eosin, magnification, × 200; Figure 5C). On immunohistochemistry, the specimen stained positive for S100, CD207 (Langerin), CD4, and CD1a, and negative for CD3 and CD20. Ki67 (MIB-1) index was slightly > 30%.

The final histological diagnosis was LCH.

The patient received chemotherapy (vindesine and prednisone acetate) after surgery.

No recurrence was observed on brain MRI at the 12-mo follow-up (Supplementary Figure 3).

LCH involving the hypothalamic-pituitary or skull is not uncommon, but involvement of the brain parenchyma, such as the frontotemporal lobe, is rare. As of January 2019, fewer than 30 cases have been reported in the PubMed database (Table 1)[6-8]. We reviewed the relevant PubMed literature from 1990 to May 2021 and found 16 cases of brain parenchymal LCH with imaging data. The mean age was 31 years (95% confidence interval: 21.5-41.2). The male-to-female ratio was 14:2, which is consistent with that reported in previous literature reviews of intracerebral LCH, but higher than that in children with LCH[3,9,10]. The lesions were mostly located in the frontotemporal lobe (14 cases), particularly in the frontal lobe. The clinical presentation of LCH is non-characteristic and varies depending on the site. Most cases showed non-specific symptoms of mass effect such as headache, seizures, hemiparesis, and/or sensory disturbances. MRI findings without contrast were also largely non-specific. Nonetheless, MRI showed hypointensity on T1WI and hyperintensity on T2WI in most cases. After administration of gadolinium, most cases showed intense homogeneous or heterogeneous enhancement. Another characteristic feature is sulcal enhancement around the lesion[6,7]. MRI images showed leptomeningeal involvement near the lesions in several cases, as reported by Kim et al[7]. This may be a characteristic sign of brain parenchymal LCH, but it needs to be confirmed in more cases.

| Ref. | Age/sex | Diameter (cm)1 | Location (Lobe) | MRI Finding | 18F-FDG PET/CT finding | ||

| T1WI | T2WI | T1WI with contrast | |||||

| Caresio et al[20], 1991 | 29/Male | 3.0 | Right temporal lobe | Hypointense | Hyperintense | Ringlike enhancement | NA |

| Itoh et al[21], 1992 | 7/Male | NA | Right frontal lobe | Hypo-/iso-intense | Hyperintense | Intense enhancement | NA |

| Bogaert et al[22], 1994 | 40/Female | NA | Left parietal lobe | Hypointense | Hyperintense | Intense enhancement | NA |

| Vital et al[23], 1996 | 32/Female | NA | Right insula lobe | NA | Hyperintense | Intense enhancement | NA |

| Grant et al[24], 1999 | 20/Male | 3.5 | Right temporal lobe | NA | NA | Intense enhancement | NA |

| Katati et al[25], 2002 | 36/Male | NA | Left temporal lobe | Hypointense | NA | Intense enhancement | NA |

| Cagli et al[9], 2004 | 24/Male | 1.5 | Left temporal lobe | Hypointense | NA | Intense enhancement | NA |

| Yamaguchi et al[26], 2004 | 2/Male | NA | Multiple lesions/bilateral frontal and temporal lobes | NA | NA | Intense enhancement | NA |

| Rodríguez-Pereira et al[10], 2005 | 30/Male | 5.0 | Left frontal lobe | NA | NA | Gyral enhancement | NA |

| Rodríguez-Pereira et al[10], 2005 | 65/Male | 2.5 | Left parietal lobe | NA | NA | Peripheral enhancement | NA |

| Dieter[27], 2017 | 4/Male | 2.01 | Multiple lesions, right frontal, and parietal lobe | Iso-/hyper-intense | Hypointense | Uniform enhancement | NA |

| Cai et al[6], 2014 | 23/Male | 4.1 | Right frontal lobe | Hypo-/iso-intense | Iso-/hyper-intense | Moderate to intense homogeneous enhancement | NA |

| Dardis et al[28], 2015 | 64/Male | NA | Multiple lesions, left frontal and right temporal lobe, and brainstem | NA | Hyperintense | Patchy enhancement | NA |

| Kim et al[7], 2018 | 36/Male | 3.0 | Right frontal lobe | Isointense | Hyperintense | Heterogeneous enhancement | NA |

| Bärtschi et al[8], 2019 | 42/Male | NA | Right insular lobe | NA | Hyperintense | Intense enhancement | NA |

| Current case | 47/Male | 3.6 | Left frontal lobe | Hypointense | Hyperintensity with hypointense areas | Heterogeneous enhancement | Lesion SUVmax 9.5 and contralateral SUVmax 8.1 |

There are no previous reports of 18F-FDG PET/CT for assessing the metabolic activity of brain parenchymal LCH. To our knowledge, our case report is the first with a PET/CT description. The SUVmax of the brain lesion was approximately 9.5, which was similar to the SUVmax of LCH lesions involving other regions reported in the literature[11]. Additional bilateral lung lesions were found, and pulmonary manifestations were decisive for diagnosis[12]. As 30% patients with LCH present with multi-organ system involvement, it is important to detect involvement of other tissues (such as the bone, soft tissue, the CNS, or the lungs)[3,13]. Single or isolated brain lesions have previously been reported based on only brain CT or MRI, without whole-body scans[6,7]. Without whole-body evaluation, reports of isolated brain lesions may be non-rigorous or biased. More recent studies that performed whole-body evaluations have identified a higher rate of focal LCH lesions than that previously reported[14,15]. Therefore, PET/CT or PET/MRI seems to be more appropriate for evaluating this disease[16]. This is especially true for combined bone and lung lesions as some case without obvious symptoms are incidentally detected; they may be missed by relying solely on radiography or CT[8]. Several studies have confirmed the diagnostic value of systemic scans, such as PET/CT or PET/MRI for LCH[14,15,17,18]. The diagnostic evaluation of LCH plays a crucial role in treatment planning. PET/CT or PET/MRI can be used to assess multiple foci throughout the body, guide biopsy sites, and assist with post-treatment strategies.

Based on prospective trials, the combination of vinblastine plus prednisolone is the most commomly used induction chemotherapy regimen and is administered over six weeks[19].

As a systemic disease, LCH has the potential to involve the brain parenchyma, and its diagnosis is extremely challenging. The use of multimodal imaging or whole-body imaging, combined with the manifestation of lesions at other sites, can be helpful in the diagnosis of this disease. Moreover, multimodality imaging is useful for assessing the systemic status of LCH, developing treatment plans, and evaluating post-treatment strategies.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Hashimoto K, Mukthinuthalapati VVPK S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: A P-Editor: Fan JR

| 1. | Rodriguez-Galindo C, Allen CE. Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood. 2020;135:1319-1331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 204] [Article Influence: 40.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Allen CE, Beverley PCL, Collin M, Diamond EL, Egeler RM, Ginhoux F, Glass C, Minkov M, Rollins BJ, van Halteren A. The coming of age of Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Nat Immunol. 2020;21:1-7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Krooks J, Minkov M, Weatherall AG. Langerhans cell histiocytosis in children: History, classification, pathobiology, clinical manifestations, and prognosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1035-1044. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 19.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Grois N, Pötschger U, Prosch H, Minkov M, Arico M, Braier J, Henter JI, Janka-Schaub G, Ladisch S, Ritter J, Steiner M, Unger E, Gadner H; DALHX- and LCH I and II Study Committee. Risk factors for diabetes insipidus in langerhans cell histiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2006;46:228-233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 202] [Cited by in RCA: 191] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Haupt R, Minkov M, Astigarraga I, Schäfer E, Nanduri V, Jubran R, Egeler RM, Janka G, Micic D, Rodriguez-Galindo C, Van Gool S, Visser J, Weitzman S, Donadieu J; Euro Histio Network. Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH): guidelines for diagnosis, clinical work-up, and treatment for patients till the age of 18 years. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60:175-184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 394] [Cited by in RCA: 419] [Article Influence: 34.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Cai S, Zhang S, Liu X, Lin Y, Wu C, Chen Y, Hu J, Wang X. Solitary Langerhans cell histiocytosis of frontal lobe: a case report and literature review. Chin J Cancer Res. 2014;26:211-214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kim JH, Jang WY, Jung TY, Moon KS, Jung S, Lee KH, Kim IY. Magnetic Resonance Imaging Features in Solitary Cerebral Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis: Case Report and Review of Literature. World Neurosurg. 2018;116:333-336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Bärtschi P, Luna E, González-López P, Abarca J, Herrero J, Costa E, Paya A, Sales J, Moreno P. A Very Rare Case of Right Insular Lobe Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis (CD1a+) Mimicking Glioblastoma Multiforme in a Young Adult. World Neurosurg. 2019;121:4-11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Cagli S, Oktar N, Demirtas E. Langerhans' cell histiocytosis of the temporal lobe and pons. Br J Neurosurg. 2004;18:174-180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Rodríguez-Pereira C, Borrás-Moreno JM, Pesudo-Martínez JV, Vera-Román JM. Cerebral solitary Langerhans cell histiocytosis: report of two cases and review of the literature. Br J Neurosurg. 2005;19:192-197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Agarwal KK, Seth R, Behra A, Jana M, Kumar R. 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose PET/CT in Langerhans cell histiocytosis: spectrum of manifestations. Jpn J Radiol. 2016;34:267-276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Vassallo R, Harari S, Tazi A. Current understanding and management of pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Thorax. 2017;72:937-945. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Albano D, Bosio G, Giubbini R, Bertagna F. Role of 18F-FDG PET/CT in patients affected by Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Jpn J Radiol. 2017;35:574-583. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ferrell J, Sharp S, Kumar A, Jordan M, Picarsic J, Nelson A. Discrepancies between F-18-FDG PET/CT findings and conventional imaging in Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2021;68:e28891. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Huynh KN, Nguyen BD. Histiocytosis and Neoplasms of Macrophage-Dendritic Cell Lineages: Multimodality Imaging with Emphasis on PET/CT. Radiographics. 2021;41:576-594. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Hashimoto K, Nishimura S, Sakata N, Inoue M, Sawada A, Akagi M. Treatment Outcomes of Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis: A Retrospective Study. Medicina (Kaunas). 2021;57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Obert J, Vercellino L, Van Der Gucht A, de Margerie-Mellon C, Bugnet E, Chevret S, Lorillon G, Tazi A. 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography-computed tomography in the management of adult multisystem Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2017;44:598-610. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Sher AC, Orth R, McClain K, Allen C, Hayatghaibi S, Seghers V. PET/MR in the Assessment of Pediatric Histiocytoses: A Comparison to PET/CT. Clin Nucl Med. 2017;42:582-588. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Gadner H, Minkov M, Grois N, Pötschger U, Thiem E, Aricò M, Astigarraga I, Braier J, Donadieu J, Henter JI, Janka-Schaub G, McClain KL, Weitzman S, Windebank K, Ladisch S; Histiocyte Society. Therapy prolongation improves outcome in multisystem Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood. 2013;121:5006-5014. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 250] [Cited by in RCA: 299] [Article Influence: 24.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Caresio JF, McMillan JH, Batnitzky S. Coexistent intra- and extracranial mass lesions: an unusual manifestations of histiocytosis X. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1991;12:82. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Itoh H, Waga S, Kojima T, Hoshino T. Solitary eosinophilic granuloma in the frontal lobe: case report. Neurosurgery. 1992;30:295-298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Bogaert J, Verschakelen JA, d'Haen B, Dom R, Wilms G. Diagnosis of atypical intracerebral Langerhans cell histiocytosis suggested by concomitant lung abnormalities. A case report. Rofo. 1994;161:369-371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Vital A, Loiseau H, Kantor G, Vital C, Cohadon F. Primary Langerhans' cell histiocytosis of the central nervous system with fatal outcome. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1996;85:1156-1160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Grant GA, Kim DK, Shaw CM, Berger MS. Solitary eosinophilic granuloma of the temporal lobe: case report and review of the literature. Brain Tumor Pathol. 1999;16:55-59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Katati MJ, Martin JM, Pastor J, Arjona V. Isolated primary Langerhans' cell histiocytosis of central nervous system. Neurocirugia (Astur). 2002;13:477-478. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Yamaguchi S, Oki S, Kurisu K. Spontaneous regression of Langerhans cell histiocytosis: a case report. Surg Neurol. 2004;62:136-40; discussion 140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Dieter S. Letter to the Editor Re: Zeidman LA, Stone J, Kondziella D. New revelations about Hans Berger, father of the electroencephalogram (EEG), and his ties to the Third Reich. J Child Neurol. 2014;29:1002-1010. J Child Neurol. 2017;32:680-681. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Dardis C, Aung T, Shapiro W, Fortune J, Coons S. Langerhans cell histiocytosis in an adult with involvement of the calvarium, cerebral cortex and brainstem: discussion of pathophysiology and rationale for the use of intravenous immune globulin. Case Rep Neurol. 2015;7:30-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |