Published online Feb 6, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i4.1388

Peer-review started: September 4, 2021

First decision: November 22, 2021

Revised: November 27, 2021

Accepted: December 25, 2021

Article in press: December 25, 2021

Published online: February 6, 2022

Processing time: 142 Days and 3.7 Hours

Severe refractory anemia during pregnancy can cause serious maternal and fetal complications. If the cause cannot be identified in time and accurately, blind symptomatic support treatment may cause serious economic burden. Thalassemia minor pregnancy is commonly considered uneventful, and the condition of anemia rarely progresses during pregnancy. Autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA) is rare during pregnancy with no exact incidence available.

We report the case of a 30-year-old β-thalassemia minor multiparous patient experiencing severe refractory anemia throughout pregnancy. We monitored the patient closely, carried out a full differential diagnosis, made a diagnosis of direct antiglobulin test-negative AIHA, and treated her with prednisone and intra

Coombs-negative AIHA should be suspected in cases of severe hemolytic anemia in pregnant patients with and without other hematological diseases.

Core Tip: Severe maternal anemia can cause serious adverse effects with a significant increase in maternal and neonatal mortality. We report the successful diagnosis and treatment of direct antiglobulin test test-negative autoimmune hemolytic anemia in a patient with β-thalassemia minor during pregnancy. The findings from this case report suggest that maternal anemia can have multiple etiologies, and blood transfusion is not always the appropriate treatment.

- Citation: Zhou Y, Ding YL, Zhang LJ, Peng M, Huang J. Direct antiglobulin test-negative autoimmune hemolytic anemia in a patient with β-thalassemia minor during pregnancy: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(4): 1388-1393

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i4/1388.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i4.1388

As an autosomal inherited hemoglobin (Hb) disorder, due to the absence or reduced synthesis of the globin chains of Hb, thalassemia has two main types, α- and β-thalassemia. Over 300 types of β-globin gene mutations have been reported causing varying degrees of reduced β-globin synthesis, usually categorized as minor, intermedia, or major on the basis of their clinical manifestations and dependence on blood transfusion[1]. China has a high prevalence of thalassemia, especially in the south of the Yangtze River. From epidemiological data, the thalassemia carrier population in China is over 30 million, among which over 1% has the major or intermedia type[2]. Patients with asymptomatic β-thalassemia minor, also known as silent carriers, who have mild microcytic, hypochromic anemia or even a normal Hb level, usually require little medical care.

Pregnancy complications are considered uncommon among β-thalassemia minor patients[3]. Aside from accurate and timely antenatal counseling, β-thalassemia minor patients do not require more frequent antenatal check-ups than normal, as this type of anemia during pregnancy rarely progresses to a serious condition that can cause significant adverse effects with a high risk of maternal mortality.

We report the case of a 30-year-old multipara with β-thalassemia minor who experienced severe hemolytic anemia throughout pregnancy. Fortunately, the maternal and fetal outcome was favorable following diagnosis and treatment. To our knowledge, this is the first report of such a case.

A 30-year-old woman, gravida 2 para 1, presented with fatigue, chest tightness, and shortness of breath for over 1 mo after activities at the 17-wk gestation.

The patient was diagnosed with severe anemia at a local hospital. Her Hb level was 40 g/L and she had several blood transfusions, but her Hb did not increase as expected and began to drop when the transfusion stopped.

Signs of anemia had not been taken seriously until the patient was hospitalized for pleuritis in 2019, when she was found to be an IVS-II-654(C>T) carrier. Her husband is not a carrier of thalassemia trait. Special medication history (other than Vitamin Complex Tablets) and transfusion history before this pregnancy were denied.

No contributory personal history or similar family history.

The patient’s vital signs were normal. She had a pale appearance, her uterus size matched the gestational age, and fetal heart rate was normal.

The patient was referred to our hospital at the 25-wk gestation. Laboratory investigations showed severe anemia, with an Hb level of 39 g/L, mean corpuscular Hb of 22.5 pg, mean corpuscular volume of 74.6 fL, and fraction of Hb A2 of 4.7%, as well as a raised bilirubin level of 34.8 µmol/L, direct bilirubin level of 15.9 µmol/L, raised lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level of 392.5 U/L, reticulocyte count of 3.15%, and haptoglobin below the detection limit. The ferritin level was 291.57 ng/mL, and B12 and folate levels were normal. Oral glucose tolerance test and other routine prenatal blood test results were within the normal range. We performed TORCH (comprising toxoplasmosis, Treponema pallidum, rubella, cytomegalovirus, herpes virus, and hepatitis viruses) serology to rule out preceding infection. Signs of intravascular hemolysis that could not be ascribed to β-thalassemia minor were observed.

Abdominal ultrasound showed a spleen diameter of 68 mm. Echocardiography demonstrated a left atrial diameter of 40 mm and mild mitral, tricuspid, and aortic regurgitation.

We carried out a multidisciplinary consultation on the third day after the patient’s admission. Taking expert opinions from a hematologist and rheumatologist, we performed further examinations. Bone marrow cytology suggested active proliferation of erythrocytes. Flow cytometry showed normal erythrocyte levels of CD55 and CD59. Connective tissue screening including antinuclear antibody and extractable nuclear antigen was also negative. A normal complement C3 level and slightly decreased C4 level were detected. We performed the direct antiglobulin test (DAT; also referred to as the "Coombs" test) including IgG and C3 several times; however, the results were negative. According to the principle of exclusion, the patient’s severe hemolytic anemia could be due to autoimmune reasons. On the other hand, the patient’s intermediate Down's screening indicated a high risk of trisomy 21; thus, a prenatal diagnosis was performed. The karyotype of the fetus was normal and copy number variation-sequencing did not find any disease-causing gene mutations.

According to the patient’s test results, the presence of intravascular hemolysis was basically established; however, the gene sequencing did not match thalassemia major. Erythrocyte CD55 and CD59 should be analyzed to rule out paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria.

The evidence for connective tissue disease was insufficient.

DAT-negative autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA) during pregnancy.

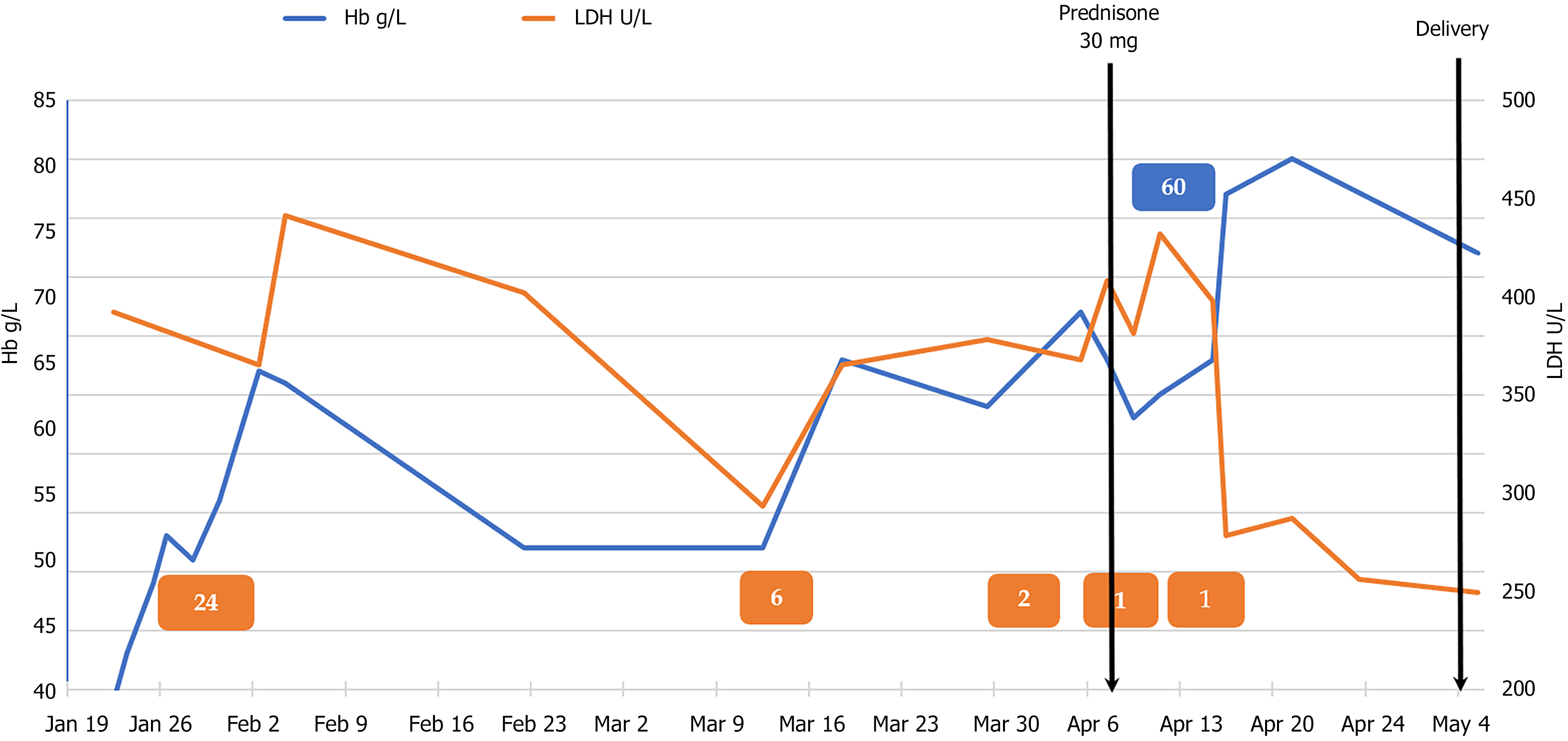

The patient was given red blood cell (RBC) transfusions with other symptomatic and supportive treatment, and the growth parameters and middle cerebral artery peak systolic velocity (MCA-PSV) of the fetus were monitored. Fortunately, fetal growth and development matched the gestational age and the MCA-PSV did not increase. The patient was discharged 2 wk later and underwent strict follow-up. She returned to her hometown for 1 mo, and at the 31-wk gestation, she underwent echocardiographic re-examination at the local hospital, which showed an atrial septal aneurysm 35 mm × 14 mm in size, indicating anemic cardiomyopathy. She was admitted to our hospital for the second time. Her blood tests still suggested severe hemolytic anemia, but this time we were very cautious regarding blood transfusion in order to avoid heart overload. We suspected that the hemolysis was due to autoimmune factors, and after discussions with the patient and her family, she was given corticosteroid and immunoglobulin therapy. She received prednisone 30 mg orally qd and intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) 20 g/d for 3 d. Her Hb level rose to > 80 g/L. The patient’s Hb and LDH values throughout pregnancy in relation to medication administration and RBC transfusion are shown in Figure 1. At 38+ wk gestation, she was given vaginal misoprostol to induce labor, following echocardiography which found no abnor

A live 3255-g boy was born by normal vaginal delivery. The neonate was transferred to the Neonatology Department 35 h after birth due to hyperbilirubinemia. Blood test results showed no sign of hemolysis; however, Hb was 136 g/L, white blood cell count was 9.07 × 109/L, platelet count was 314 × 109/L, and inflammatory indicators were elevated, indicating neonatal infection, and he had inherited the same IVS-II-654(C>T) mutation from his mother. The neonate was discharged after antibiotic treatment and phototherapy 10 d later. The mother discontinued oral corticosteroid postnatally, and maintained an Hb level above 90 g/L.

β-thalassemia carriers are asymptomatic; however, little research is available on the pregnancy outcome of β-thalassemia carriers, although it has been reported that the incidence of intrauterine growth retardation and oligohydramnios is higher[3-5]. It is recommended that pregnant women with mild thalassemia should follow the health care guidelines for normal pregnancy[6]. Thalassemia carriers tend to become more anemic during pregnancy, and it is commonly believed that this is due to physio

AIHA is characterized by the production of RBC autoantibodies, accelerating their destruction[7]. The incidence of AIHA in the general population is 1/100.000[8]. AIHA is rare during pregnancy, and the exact incidence has not been reported[9,10]. It has been reported that ovarian teratomas were suggested as a possible trigger of AIHA in pregnant and non-pregnant patients[11]. The diagnosis is generally based on the presence of anemia along with signs of hemolysis such as reticulocytosis, low haptoglobin, increased LDH, elevated indirect bilirubin, and a positive DAT. DAT-negative AIHA, as in our patient, only occurs in 5%-10% of all cases, and requires more specific detection with new diagnostic tools[7,9]. Due to insufficient knowledge and conditions, we did not perform a more sensitive DAT test such as anti-IgA and IgM antisera[12], and there is still room for improvement in this area. The prognosis is usually favorable once an accurate diagnosis of AIHA has been made, patients usually respond to first-line corticosteroids, and AIHA resolves after delivery[13]. Other treatments include RBC transfusions and IVIG. It was reported that cyclosporine A was safe and effective in a case of β-thalassemia major, AIHA, and insulin treated diabetes mellitus when first-line corticosteroids were unsuitable[14]. Research focused on AIHA in patients with thalassemia is very limited. Available reports are usually on alloimmunization in thalassemia major patients after receiving multiple blood transfusions. A multicenter study showed that erythrocyte autoantibodies occurred in 6.5% of chronically or intermittently transfused thalassemia patients[15]. As reported, the presence of underlying RBC autoantibodies may be predictors of AIHA in β-thalassemia patients[16]. Our thalassemia patient was not transfusion dependent, and as pregnancy is a semi-allogeneic process, we thought that there might be potential links between these three pathological processes.

We report a rare case of severe refractory anemia during pregnancy. Following various examinations, the underlying cause of the anemia was finally identified, and the patient received timely treatment. Very little research has been carried out on AIHA in pregnant patients with thalassemia. Little is known about possible pathologic process and ignoring it can lead to delays in treatment and adverse pregnancy outcome. We suggested that DAT-negative AIHA should be suspected in cases of severe hemolytic anemia in pregnant patients with and without other hematological diseases. Hopefully, there will be more detailed and in-depth studies carried out on this issue in the future.

Special thanks to the nurses and physicians for their care of this patient.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Obstetrics and gynecology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Naem AA, Tolunay HE S-Editor: Li X L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Li X

| 1. | Taher AT, Weatherall DJ, Cappellini MD. Thalassaemia. Lancet. 2018;391:155-167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 383] [Cited by in RCA: 515] [Article Influence: 73.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Society of Perinatal Medicine; Chinese Medical Association; Obstetric Subgroup; Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology; Chinese Medical Association. Experts’ consensus on thalassaemia during pregnancy. Zhonghua Weichan Yixue Zazhi. 2020;23:577-584. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 3. | Tsatalas C, Chalkia P, Pantelidou D, Margaritis D, Bourikas G, Spanoudakis E. Pregnancy in beta-thalassemia trait carriers: an uneventful journey. Hematology. 2009;14:301-303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Leung TY, Lao TT. Thalassaemia in pregnancy. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2012;26:37-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Sheiner E, Levy A, Yerushalmi R, Katz M. Beta-thalassemia minor during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103:1273-1277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Management of Beta Thalassaemia in Pregnancy. Green-top Guideline No. 66. March 2014. Available from: https://www.rcog.org.uk/globalassets/documents/guidelines/gtg_66_thalassaemia.pdf. |

| 7. | Barcellini W, Fattizzo B. The Changing Landscape of Autoimmune Hemolytic Anemia. Front Immunol. 2020;11:946. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 16.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Rigal D, Meyer F. [Autoimmune haemolytic anemia: diagnosis strategy and new treatments]. Transfus Clin Biol. 2011;18:277-285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kamesaki T. [Diagnosis and classification of direct antiglobulin test-negative autoimmune hemolytic anemia]. Rinsho Ketsueki. 2021;62:456-462. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Maroto A, Martinez-Diago C, Tio G, Sagues M, Borrell A, Bonmati A, Teixidor M, Adrados C, Torrent S, Alvarez E. Autoimmune hemolytic anemia in pregnancy: a challenge for maternal and fetal follow-up. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020;1-3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Felemban AA, Rashidi ZA, Almatrafi MH, Alsahabi JA. Autoimmune hemolytic anemia and ovarian dermoid cysts in pregnancy. Saudi Med J. 2019;40:397-400. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Genty I, Michel M, Hermine O, Schaeffer A, Godeau B, Rochant H. [Characteristics of autoimmune hemolytic anemia in adults: retrospective analysis of 83 cases]. Rev Med Interne. 2002;23:901-909. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Fattizzo B, Ferraresi M, Giannotta JA, Barcellini W. Secondary Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis and Autoimmune Cytopenias: Case Description and Review of the Literature. J Clin Med. 2021;10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Agapidou A, Vlachaki E, Theodoridis T, Economou M, Perifanis V. Cyclosporine therapy during pregnancy in a patient with β-thalassemia major and autoimmune haemolytic anemia: a case report and review of the literature. Hippokratia. 2013;17:85-87. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Vichinsky E, Neumayr L, Trimble S, Giardina PJ, Cohen AR, Coates T, Boudreaux J, Neufeld EJ, Kenney K, Grant A, Thompson AA; CDC Thalassemia Investigators. Transfusion complications in thalassemia patients: a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CME). Transfusion. 2014;54:972-81; quiz 971. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Khaled MB, Ouederni M, Sahli N, Dhouib N, Abdelaziz AB, Rekaya S, Kouki R, Kaabi H, Slama H, Mellouli F, Bejaoui M. Predictors of autoimmune hemolytic anemia in beta-thalassemia patients with underlying red blood cells autoantibodies. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2019;79:102342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |