Published online Feb 6, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i4.1349

Peer-review started: August 12, 2021

First decision: October 20, 2021

Revised: October 22, 2021

Accepted: December 23, 2021

Article in press: December 23, 2021

Published online: February 6, 2022

Processing time: 165 Days and 2.4 Hours

Rhabdomyolysis develops as a result of skeletal muscle cell collapse from leakage of the intracellular contents into circulation. In severe cases, it can be associated with acute kidney injury and disseminated intravascular coagulation, leading to life threatening outcomes. Rhabdomyolysis can occur in the perioperative period from various etiologies but is rarely induced by tourniquet use during orthopedic surgery.

A 77-year-old male underwent right total knee arthroplasty using a tourniquet under spinal anesthesia. About 24 h after surgery, he was found in a drowsy mental state and manifested features of severe rhabdomyolysis, including fever, hypotension, oliguria, high creatine kinase, myoglobinuria, and disseminated intravascular coagulation. Despite supportive care, cardiac arrest developed abruptly, and the patient was not able to be resuscitated.

Severe rhabdomyolysis and disseminated intravascular coagulation can develop from surgical tourniquet, requiring prompt, aggressive treatments to save the patient.

Core Tip: Although total knee arthroplasty under spinal anesthesia using a tourniquet is widely performed in elderly patients, physicians should be aware of the possibility of tourniquet-induced rhabdomyolysis after surgery. Careful use of a tourniquet and maintaining an adequate hemodynamic state in the perioperative period is important to prevent rhabdomyolysis. Nonspecific symptoms, such as altered mental state, can obscure a prompt diagnosis and delay early treatment. Regular monitoring and careful evaluations are necessary to detect rhabdomyolysis early, and aggressive therapies, including early vigorous hydration, are required.

- Citation: Yun DH, Suk EH, Ju W, Seo EH, Kang H. Fatal rhabdomyolysis and disseminated intravascular coagulation after total knee arthroplasty under spinal anesthesia: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(4): 1349-1356

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i4/1349.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i4.1349

Rhabdomyolysis is a clinical syndrome caused by the destruction of skeletal muscle fibers, which leads to the leakage of intracellular contents into circulation. Various toxic materials, such as creatine kinase (CK), lactate dehydrogenase, myoglobin, aspartate transaminase (AST), and electrolytes, are released to the bloodstream, causing systemic symptoms, including hyperkalemia, hypovolemia, acute kidney injury (AKI), metabolic acidosis, compartment syndrome, cardiac dysrhythmia, and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) in severe cases[1]. Rhabdomyolysis can be classified according to the mechanism of injury, such as hypoxic, physical, chemical, or biological, or classified as acquired or inherited. Trauma is the most common cause, with less common causes being toxins, drugs, alcohol, infection, sepsis, excessive workouts, myopathies, endocrinopathies, thermal injury, and electrolyte abnormalities[2].

As a form of trauma, surgery can induce rhabdomyolysis due to ischemic muscle injury from long-term immobilization or excessive tissue compression during the surgery. Recently, there have been increasing numbers of descriptions of rhabdomyolysis which developed in the perioperative period. The use of a pneumatic tourniquet, which is widespread in extremity orthopedic surgery to create a bloodless operation field, is rarely associated with morbidity and mortality but can induce rhabdomyolysis. In this report, we present an unusual case of tourniquet-induced rhabdomyolysis after total knee arthroplasty (TKA) under spinal anesthesia, which was ultimately fatal.

A 77-year-old male (weight: 51 kg, height: 170 cm) exhibited a drowsy mental state about 24 h after TKA.

The patient had been diagnosed with unstable angina 8 years prior, which was treated with a coronary stent insertion. He had been subsequently treated with Sigmart (nicorandil 5 mg; JW Pharmaceutical, Seoul, South Korea), aspirin (enteric coated tab, 100 mg), Almarl (arotinolol 5 mg; HK inno.N, Seoul, South Korea), and Herben (diltiazem 30 mg; HK inno.N).

Prior to surgery, chest X-ray was normal. Echocardiogram showed a left ventricular ejection fraction of 61%, grade 2 diastolic dysfunction, mild aortic regurgitation, trivial mitral regurgitation and tricuspid regurgitation. All hematological parameters were unremarkable, with normal blood urea nitrogen/creatinine (BUN/Cr) of 11.0/0.8 mg/dL and low hemoglobin of 11.9 g/dL.

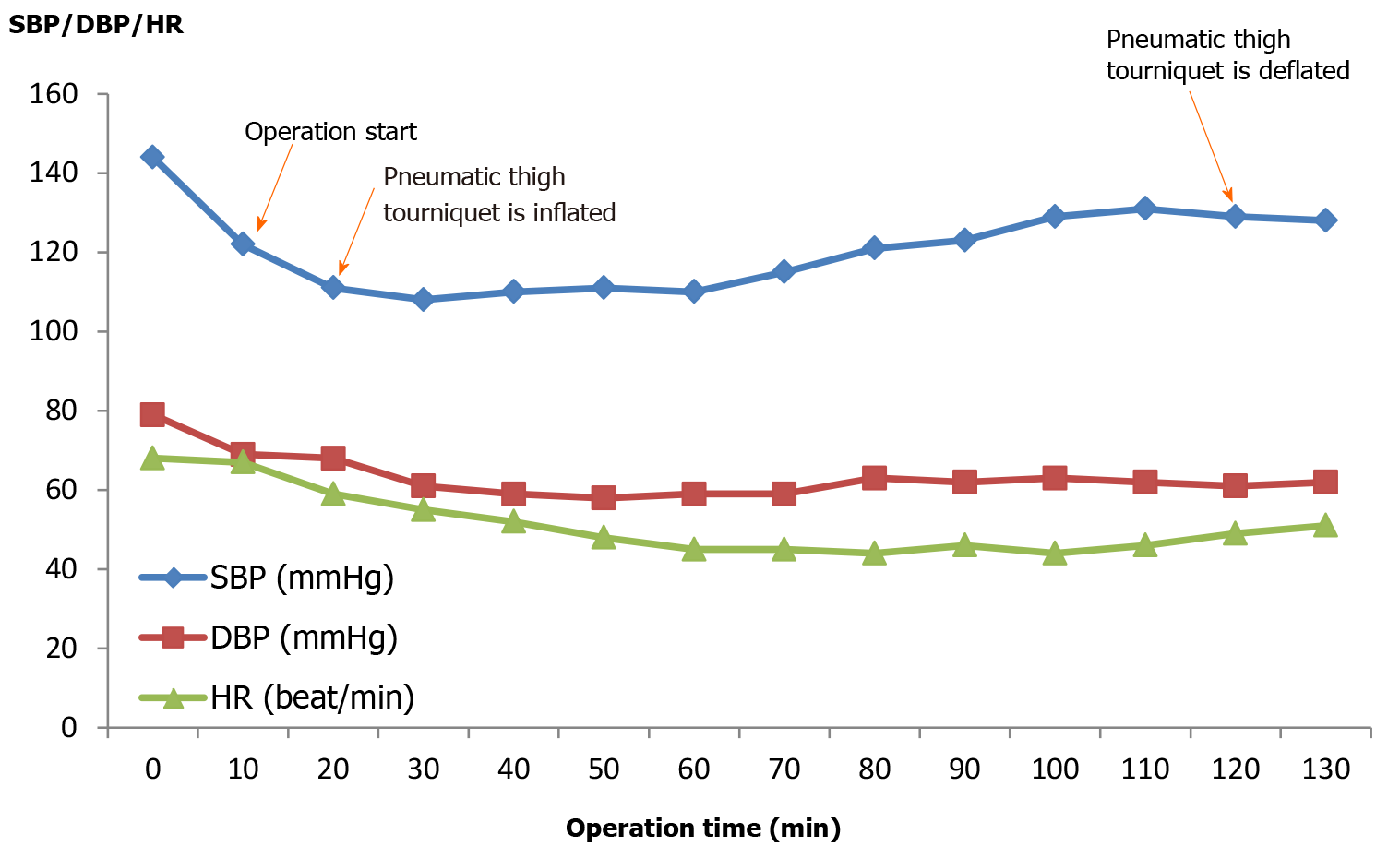

Aspirin was stopped 7 d before surgery, and no medication was administered on the morning of surgery. After arriving at the operating room, initial vital signs were blood pressure (BP) of 144/79 mmHg, heart rate (HR) of 68 beats/min, and SpO2 of 97%. Bupivacaine (0.5%, 10 mg) was injected into the subarachnoid space at T10 for the spinal block. Intravenous dexmedetomidine was infused (0.5 μg/kg/min for first 10 min, then at 0.4-0.6 μg/kg/min) for sedation. A pneumatic thigh tourniquet was applied intraoperatively at an inflation pressure of 300 mmHg for 100 min. Total anesthesia time was 2 h and 10 min. During surgery, 600 mL of crystalloid was administered and 150 mL of urine were collected. Estimated blood loss was 90 mL. Intraoperative vital signs showed BP of 100-130/50-70 mmHg, HR of 45-55 beats/min, and SpO2 of 97%-99% (Figure 1).

On arrival in the recovery room, initial vital signs were BP of 97/55 mmHg, HR of 41 beats/min and SpO2 of 100%. During the first hour of recovery, vital signs were maintained as follows: BP of 95-100/55-60 mmHg, HR of 40-45 beats/min, and SpO2 of 98%-100%. About 90 mL of urine and 70 mL of blood were drained, and 400 mL of crystalloid was administered.

After surgery, post-operative pain was managed with an intravenous patient-controlled analgesia (AutoFuser; ACE Medical, Beverly Hills, CA, United States), including 1 mg fentanyl (Hana Pharm, Seoul, South Korea), of which the baseline infusion rate, bolus demand dose, and lock-out time were 2 mL/h, 2 mL, 15 min. Antibiotics (Refosporen, 1 g and cefazedone sodium 1 g; both from Hanall Biopharma, Seoul, Korea) were also injected bid. The morning following surgery, the patient complained of severe pain on the right thigh and overnight shivering. Tridol Injection (tramadol hydrochloride 50 mg/mL; Yuhan Pharm, Seoul, South Korea) was injected for pain control.

When the mental change was identified, the patient’s mental state was assessed with a Glasgow coma scale score of 8/15 (M5/V2/E1). At that time, vital signs were BP of 110/70 mmHg, HR of 122 beats/min, body temperature of 37.9 °C, and SpO2 of 86%-90%. Electrocardiogram was normal.

On physical examination, the patient’s right thigh, which had been cuffed with tourniquet during the operation, was stiff and had turned a dark brown, without swelling, whereas the surgical site and distal extremity were unaffected. Urine collected in a Foley bag was dark colored, and the urine output every 8 h after operation was 100 mL, 220 mL, and 250 mL, respectively, for a total of 570 mL/d, which indicated oliguria.

Immediately after surgery in the recovery room, laboratory results were within the normal range, with the exception for some derangement in the coagulation panel. About 19 h after surgery, CK was markedly increased to 2763 IU/L (normal: 56-244 IU/L), creatine kinase-myocardial band (CK-MB) was elevated to 13.26 ng/mL (normal: < 4.87 ng/mL), and AST and BUN/Cr were also elevated. However, troponin-I was normal at 0.100 ng/mL (normal: < 0.16 ng/mL). Prolonged coagulation battery, thrombocytopenia, and high levels of fibrinogen degradation product and D-dimer were detected in the early postoperative phase, and serial tests demonstrated progressive deterioration of DIC. Additional laboratory tests performed during the intensive care unit (ICU) stay showed continued deterioration of the parameters. Serial changes in the parameters are summarized in Table 1.

| Time | CK, 56-244 IU/L | AST, 5-37 U/L | LDH, 160-520 U/L | BUN, 8-22 mg/dL | Cr, 0.8-1.2 mg/dL | K, 3.5-5.0 mEq/L | Platelet count, 150-400 ×103/mL | PT/aPTT, 10.4-13.5/36.0-39.0 s | PT INR, 0.85-1.15 INR | Fibrinogen, 170-410 mg/dL | D-dimer, 0-0.55 mg/mL | FDP, 0-5 mg/mL | pH |

| Preop. | 27 | 11 | 0.8 | 4.1 | 111 | 11.3/30.8 | 1 | ||||||

| After surgery | 111 | 26 | 10.4 | 0.7 | 3.5 | 91 | 12.2/28.8 | 1.09 | 198 | 4.14 | 10.2 | ||

| 19 h after surgery (next day morning) | 2763 | 93 | 15.2 | 1 | 3.5 | 52 | 13.8/32.8 | 1.24 | 150 | 80 | 148 | 7.383 | |

| 31 h after surgery (during ICU) | 121 | 464 | 20.4 | 1.2 | 3.7 | 44 | 17.3/37.9 | 1.58 | 361 | 48.3 | 117 | 7.406 | |

| 33 h after surgery (during CPR) | 3455 | 128 | 502 | 19.5 | 1.4 | 5.3 | 16 | 31.7/120.3 | 3.02 | 171 | 80 | 140 | 7.511 |

Immediately after the mental change was identified, brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed for differential diagnosis. Mild small vessel disease was identified, but no notable hemorrhage or infarction was evident.

As the patient persisted in the drowsy mental state, additional tests found that serum myoglobin was 1027 ng/mL (normal: 28-72 ng/mL), and random urine analysis revealed that urine myoglobin was 25.3 ng/mL and red blood cell count was 100/high powered field (HPF) (normal: 0-4/HPF).

Tourniquet-induced rhabdomyolysis was diagnosed based on the serum CK level (5 times the upper limit of normal range), myoglobinuria, and physical examination. Laboratory findings revealed that AKI (AKIN criteria stage 1, urine output < 0.5 mL/kg/h for 6-12 h and serum Cr increase 0.3 mg/dL within 48 h) and DIC accompanied the rhabdomyolysis.

About 1 h after the change in the patient’s mental status, BP dropped to 88/62 mmHg, and norepinephrine (0.5-1 μg/kg/min) was infused to maintain systolic BP above 100 mmHg. After brain MRI examination, the patient was admitted to the ICU. An arterial line was placed in the left radial artery for continuous monitoring of blood pressure, and a central line was secured in the right internal jugular vein for adequate fluid supply and cardiovascular monitoring. A nephrologist was consulted, and fluid treatment of 5 L/d was prescribed. Dialysis was scheduled due to progressive renal impairment. Fluid loading was initiated with normal saline at 400 mL/h for 2 h, and then decreased to 250 mL/h. For renoprotection, Lasix (furosemide, 20 mg injection; Handok, Seoul, South Korea) and sodium bicarbonate (40 mL injection of 8.4%; Jeil Pharmaceutical, Daegu, South Korea) were administered for diuresis and urine alkalization, respectively. The urine output was 110 mL for the first 3 h and 600 mL for next 4 h. Denogan (propacetamol hydrochloride 1 g injection; Yungjin Pharmaceutical, Seoul, South Korea) was administered to control fever. About 2 h after fluid administration, the patient’s mental status was restored to alert. His vital signs were as fo

| Time | SBP in mmHg | DBP in mmHg | HR in beats/min | BT in ℃ | SpO2, % | Progress note |

| Before surgery | 120 | 70 | 50 | 36.6 | 100 | After arrival on operation room |

| After surgery | 95 | 58 | 48 | 35.8 | 100 | During recovery room |

| 6 h after surgery | 120 | 70 | 61 | 36.4 | 100 | |

| 12 h after surgery | 100 | 60 | 75 | 36.1 | 100 | |

| 24 h after surgery | 110 | 70 | 110 | 37.9 | 90 | Drowsy mental state |

| 28 h after surgery | 100 | 70 | 103 | 36.6 | 98 | During ICU, mental state was recovered |

| 31 h after surgery | 100 | 60 | 113 | 38 | 96 | |

| 33 h after surgery | 50 | 20 | 37 | 52 | During CPR |

Approximately 5 h after the patient’s mental state was restored, his BP and HR dropped suddenly, followed by cardiac arrest. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation was performed for about 1 h; however, the patient was not resuscitated. At the will of the guardian, we stopped further resuscitation, and he expired.

Rhabdomyolysis has been described during the perioperative period after various types of surgeries, including urologic, spinal, coronary bypass graft, bariatric, and head and neck. Risk factors for developing rhabdomyolysis during surgery and subsequent post-operative period are: prolonged surgical duration, improper positioning, male sex, obesity, age < 10 or > 60 years, diabetes, hypertension, kidney disease, endocrine disease, chronic drug users, and sepsis[3-6].

Excessive or prolonged compression by a pneumatic tourniquet during a lower extremity surgery can bring about tissue ischemia, both beneath the cuff and in the distal tissue, which can therefore lead to rhabdomyolysis. However, this is a rare outcome, as only a few cases of rhabdomyolysis after tourniquet application in lower extremity surgery have been reported[7-12]. Tourniquet-induced rhabdomyolysis occurs regardless of the anesthetic type and is generally related to longer tourniquet application times and unusually high tourniquet pressures. Therefore, it is important to control the tourniquet application time and pressure to prevent rhabdomyolysis.

Although optimal tourniquet pressure and inflation time for prevention of muscle injury have not been clearly defined, several methods are used to determine the optimal inflation pressure for lower extremity. The first is determined by adding 100-150 mmHg above the arm systolic blood pressure[13], and a second is by adding 50-75 mmHg to the pressure required to obliterate the peripheral pulse on Doppler probe[14]. Additionally, Horlocker et al[15] recommended the tourniquet inflation time < 120 min to prevent nerve injury during TKA not pertaining to muscle injury. In TKA, tourniquet is usually used at 300 mmHg of pressure until completion of cementing and total inflation time is limited to 120 min. If the operation is expected to be longer, the tourniquet should be deflated for a minimum of 20 min every 60-90 min[16].

Besides the optimal use of tourniquet, the safe inflation pressure and time seem to be dependent on several variables. For example, underlying conditions of a patient are also important in predicting the development of rhabdomyolysis after tourniquet application. Additionally, factors, including age, blood pressure, co-morbidities and the condition of the extremity, should also be considered when assessing the risks of developing rhabdomyolysis after using a tourniquet during surgery. To our know

Rhabdomyolysis can be precipitated by hypotension or hypovolemia due to the distortion of perfusion to the affected muscles. Glassman et al[17] suggested that permissive hypertension would prevent the development of rhabdomyolysis by improving perfusion to compressed muscles. In TKA, tourniquet use significantly decreases intraoperative blood loss but cannot decrease total blood loss[18], therefore sufficient fluid should be supplied postoperatively after tourniquet deflation when persistent bleeding is ongoing. In our patient, the tourniquet pressure and duration did not exceed the recommended guidelines, with 300 mmHg of pressure applied for 100 min. The patient had two known risk factors of male sex and old age. Additionally, preoperative dehydration, sustained postoperative hypotension, and his history of ischemic heart disease are thought to be contributing factors of the rhabdomyolysis development, as together these conditions contributed to peripheral vascular insufficiency. Moreover, postoperative shivering and fever may have limited tissue perfusion and oxygen supply, and overlapping AKI and DIC cascade further led to the rapid progression of the disease.

TKA is usually performed on older patients, many with various underlying diseases, and spinal anesthesia is preferred in lower extremity surgery for elderly patients to avoid risks of general anesthesia. However, hypotension induced by spinal block and dexmedetomidine infusion for sedation might have contributed to rhabdomyolysis by lowering perfusion pressure. Therefore, meticulous care in tourniquet use and maintaining adequate perfusion pressure are required to prevent muscle injury. We recommend the lowest effective inflation pressure with minimal inflation time in TKA because the tourniquet inflation time and pressure have additive effects.

The diagnosis of rhabdomyolysis in our patient was confirmed by elevated serum CK levels of > 1000 U/L, which is 5-times the normal upper limit. The patient also had dark urine and severe pain in the area the tourniquet was applied. Clinical suspicion is important to make a timely decision for diagnosis, so physicians should pay attention to the clinical presentations. The symptoms of this syndrome vary, from minor and subclinical to severe and even fatal, according to the degree of skeletal muscle injury. Musculoskeletal signs are inappropriate severe pain, occasional tenderness or swelling in the affected muscle, and skin changes, indicating muscle necrosis can be present. Simple myalgia, fatigue, weakness, fever, tachycardia, nausea, and vomiting are common general manifestations, and pigmenturia can be observed in some cases. Non-specific symptoms, such as hypotension, shock and changes in mental status, might be present, requiring differential diagnosis. Complications of rhabdomyolysis are hyperkalemia, hypocalcemia, elevated AST, cardiac dysrhythmias, and cardiac arrest in early phase. AKI and DIC can develop, usually 12-72 h after insult, as late complications in serious cases.

In our patient, clotting studies detected an early DIC cascade in the postoperative period. Although fibrinolysis is activated transiently after tourniquet use itself, myocyte components can activate the coagulation pathway leading to DIC in severe rhabdomyolysis[1]. Persistent oliguria and progressive increase in creatine levels showed ongoing kidney injury. AKI is the most common serious complication of rhabdomyolysis, occurring in approximately 10%-67%. The mortality rate of rhabdomyolysis is known to about 10%, which increases with the degree of kidney injury up to 50%[19]. AKI is an independent predictor of higher mortality and more likely to develop in elderly patients and in patients with chronic comorbid disease, such as congestive heart failure, coronary artery disease, diabetes mellitus, atrial fibrillation, hyperlipidemia, and chronic kidney disease[20].

Although clear guidelines for the management of rhabdomyolysis have not yet been developed, the goals of rhabdomyolysis treatment are the same as maintaining adequate tissue perfusion and oxygenation to prevent hypoxic tissue injury and preserving renal function by maintaining urine output. Prompt fluid replacement is the keystone of treatment. Aggressive hydration should be initiated as soon as possible to control hypovolemia and maintain adequate urine output (> 200-300 mL/h in adult). High volume fluid replacement, up to 1.5 L/h or more than 6 L/d, may be needed to obtain satisfactory urine output[21,22]. Mannitol, loop diuretics, and sodium bicarbonate have been used for renal protection, but the additional benefit beyond fluid resuscitation is not known. Renal replacement therapy can be considered in deteriorating kidney function, uncontrolled hyperkalemia, metabolic acidosis, and fluid overload. In the present case, early mental changes prompted a brain MRI to rule out intracranial accident. Unfortunately, the treatment of rhabdomyolysis, such as early hydration, was delayed during the radiological study. After radiological work up, the patient was transferred to the ICU, and urine output was found to be inadequate, despite fluid replacement and pharmacological renoprotection. Higher volume expansion should have been performed in order to achieve satisfactory urine output. We thought that the unresolved dehydration and overlapping DIC cascade resulted in the devastating outcome.

Rhabdomyolysis induced by tourniquet application is very rare, but can lead to potentially lethal results if it develops. Physicians should be aware of the possibility of tourniquet-induced rhabdomyolysis after TKA, regardless of the type of anesthesia. Tourniquets should be used carefully in elderly patients with risk factors, and maintaining hemodynamic stability with adequate fluid replacement is important during the perioperative period. Regular monitoring of CK level and sufficient attention are necessary to detect this syndrome early. Once rhabdomyolysis is diagnosed, prompt aggressive treatments, including vigorous hydration, are required to save the patient, especially when accompanied by AKI or DIC.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Anesthesiology

Country of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Liu W S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Warren JD, Blumbergs PC, Thompson PD. Rhabdomyolysis: a review. Muscle Nerve. 2002;25:332-347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 287] [Cited by in RCA: 282] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Huerta-Alardín AL, Varon J, Marik PE. Bench-to-bedside review: Rhabdomyolysis -- an overview for clinicians. Crit Care. 2005;9:158-169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 486] [Cited by in RCA: 556] [Article Influence: 26.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Landau ME, Kenney K, Deuster P, Campbell W. Exertional rhabdomyolysis: a clinical review with a focus on genetic influences. J Clin Neuromuscul Dis. 2012;13:122-136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Chakravartty S, Sarma DR, Patel AG. Rhabdomyolysis in bariatric surgery: a systematic review. Obes Surg. 2013;23:1333-1340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Iwere RB, Hewitt J. Myopathy in older people receiving statin therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;80:363-371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Pariser JJ, Pearce SM, Patel SG, Anderson BB, Packiam VT, Shalhav AL, Bales GT, Smith ND. Rhabdomyolysis After Major Urologic Surgery: Epidemiology, Risk Factors, and Outcomes. Urology. 2015;85:1328-1332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Lee YG, Park W, Kim SH, Yun SP, Jeong H, Kim HJ, Yang DH. A case of rhabdomyolysis associated with use of a pneumatic tourniquet during arthroscopic knee surgery. Korean J Intern Med. 2010;25:105-109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Karcher C, Dieterich HJ, Schroeder TH. Rhabdomyolysis in an obese patient after total knee arthroplasty. Br J Anaesth. 2006;97:822-824. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Palmer SH, Graham G. Tourniquet-induced rhabdomyolysis after total knee replacement. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1994;76:416-417. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Shenton DW, Spitzer SA, Mulrennan BM. Tourniquet-induced rhabdomyolysis. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990;72:1405-1406. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Sheth NP, Sennett B, Berns JS. Rhabdomyolysis and acute renal failure following arthroscopic knee surgery in a college football player taking creatine supplements. Clin Nephrol. 2006;65:134-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Vold PL, Weiss PJ. Rhabdomyolysis from tourniquet trauma in a patient with hypothyroidism. West J Med. 1995;162:270-271. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Crenshaw A, Canale S, Beaty J. Surgical techniques and approaches. 2007, 3-5. |

| 14. | Reid HS, Camp RA, Jacob WH. Tourniquet hemostasis. A clinical study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1983;230-234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Horlocker TT, Hebl JR, Gali B, Jankowski CJ, Burkle CM, Berry DJ, Zepeda FA, Stevens SR, Schroeder DR. Anesthetic, patient, and surgical risk factors for neurologic complications after prolonged total tourniquet time during total knee arthroplasty. Anesth Analg. 2006;102:950-955. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Arthur JR, Spangehl MJ. Tourniquet Use in Total Knee Arthroplasty. J Knee Surg. 2019;32:719-729. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Glassman DT, Merriam WG, Trabulsi EJ, Byrne D, Gomella L. Rhabdomyolysis after laparoscopic nephrectomy. JSLS. 2007;11:432-437. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Cai DF, Fan QH, Zhong HH, Peng S, Song H. The effects of tourniquet use on blood loss in primary total knee arthroplasty for patients with osteoarthritis: a meta-analysis. J Orthop Surg Res. 2019;14:348. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | McKenna MC, Kelly M, Boran G, Lavin P. Spectrum of rhabdomyolysis in an acute hospital. Ir J Med Sci. 2019;188:1423-1426. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Yang CW, Li S, Dong Y, Paliwal N, Wang Y. Epidemiology and the Impact of Acute Kidney Injury on Outcomes in Patients with Rhabdomyolysis. J Clin Med. 2021;10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Khan FY. Rhabdomyolysis: a review of the literature. Neth J Med. 2009;67:272-283. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Scharman EJ, Troutman WG. Prevention of kidney injury following rhabdomyolysis: a systematic review. Ann Pharmacother. 2013;47:90-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |