Published online Dec 26, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i36.13418

Peer-review started: September 16, 2022

First decision: November 11, 2022

Revised: November 21, 2022

Accepted: December 5, 2022

Article in press: December 5, 2022

Published online: December 26, 2022

Processing time: 101 Days and 13.2 Hours

Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia (SAB) is among the leading causes of bacteraemia and infectious endocarditis. The frequency of infectious endocarditis (IE) among SAB patients ranges from 5% to 10%-12%. In adults, the characteristics of epidermolytic hyperkeratosis (EHK) include hyperkeratosis, erosions, and blisters. Patients with inflammatory skin diseases and some diseases involving the epidermis tend to exhibit a disturbed skin barrier and tend to have poor cell-mediated immunity.

We describe a case of SAB and infective endocarditis in a 43-year-old male who presented with fever of unknown origin and skin diseases. After genetic tests, the skin disease was diagnosed as EHK.

A breached skin barrier secondary to EHK, coupled with inadequate sanitation, likely provided the opportunity for bacterial seeding, leading to IE and deep-seated abscess or organ abscess. EHK may be associated with skin infection and multiple risk factors for extracutaneous infections. Patients with EHK should be treated early to minimize their consequences. If patients with EHK present with prolonged fever of unknown origin, IE and organ abscesses should be ruled out, including metastatic spreads.

Core Tip: Emergency physicians often encounter patients with fever of unknown origin, some of who present with skin diseases. We hope the case can heighten awareness that, in patients with epidermolytic hyperkeratosis or other skin diseases presented with prolonged pyrexia, infectious endocarditis, Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia and organ abscess could be identified and treated early to minimize the consequences and avoid further life-threatening episodes.

- Citation: Chen Y, Chen D, Liu H, Zhang CG, Song LL. Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia and infective endocarditis in a patient with epidermolytic hyperkeratosis: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(36): 13418-13425

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i36/13418.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i36.13418

Epidermolytic hyperkeratosis (EHK), originally termed bullous congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma, is a rare autosomal dominant disorder caused by mutations in keratins 1 and 10. It has characteristics of erythema, blistering, erosions and skin denudation present at birth and develop marked hyperkeratosis in adults[1,2]. EHK is easy to distinguish from other congenital ichthyoses through its pathological features[2]. These manifestations are due to mutations in genes mostly involved in skin barrier formation. When the skin barrier function is significantly impaired, it can lead to hypernatremic dehydration, impaired thermoregulation, increased risk for eletrolyte imbalances and infection. A breached skin barrier secondary to EHK is likely to provide the opportunity for bacterial seeding and invasion, leading to Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia (SAB) and infectious endocarditis, as in our case. We discuss a case of SAB and infective endocarditis in a 43-year-old man with EHK and no history of drug addiction.

A 43-year-old male presented with a 10-d history of pyrexia, fatigue, diarrhoea, and weight loss.

Upon presentation, he was pyrexial at 39°C, accompanied by fatigue, confusion, and diarrhoea.

He regarded his skin disease as psoriasis since childhood, with recurrently diffuse palmoplantar hyperkeratosis, erythema and hypernatremia on the flexor surfaces of both arms. He was not on regular medications and had never sought medical advice about his hyperkeratosis. He had never smoked, did not drink alcohol, and had no history of drug addiction. The patient had never received professional dermatological treatment.

The patient had no significant prior family history.

The patient was pyrexial at 39°C with a blood pressure of 132/78 mmHg on admission. His hyperkeratosis affected his upper and lower limbs as diffuse palmoplantar hyperkeratosis, erythema, and scales on the flexor surfaces of both arms (Figure 1). He had a systolic murmur over the mitral area but did not exhibit the meningeal irritation sign or cardiopulmonary or abdominal issues.

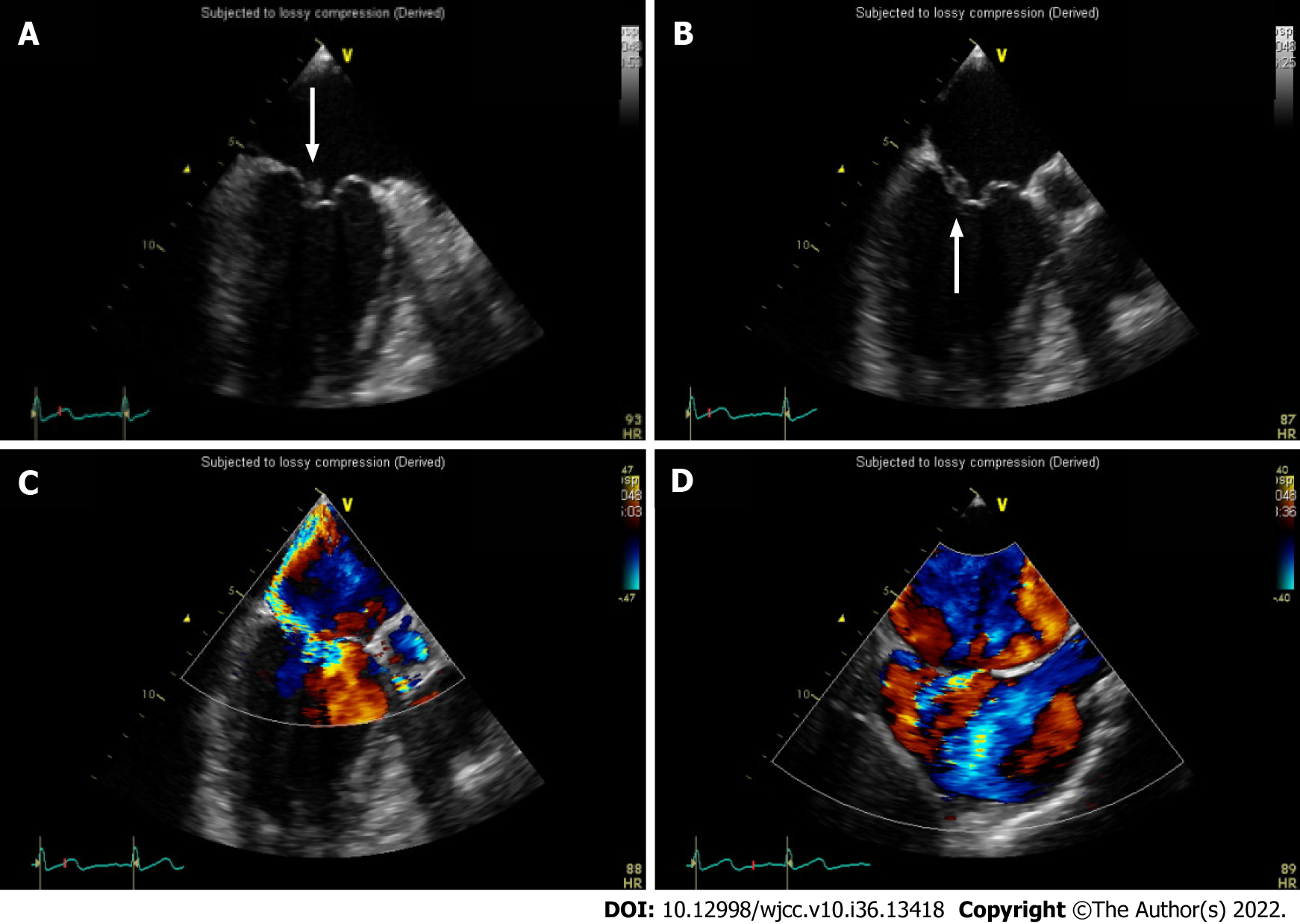

White cell counts and C-reactive protein levels were elevated to 17.07 × 109 cells/L and above 250 mg/L, respectively. His procalcitonin levels were 3.38 ng/mL. His tests for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and syphilis antibodies were negative. His electrocardiogram showed sinus tachycardia. Blood cultures isolated methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) 2 and 4 d after admission to the hospital. Transthoracic echocardiography indicated mitral valve disease with severe insufficiency.

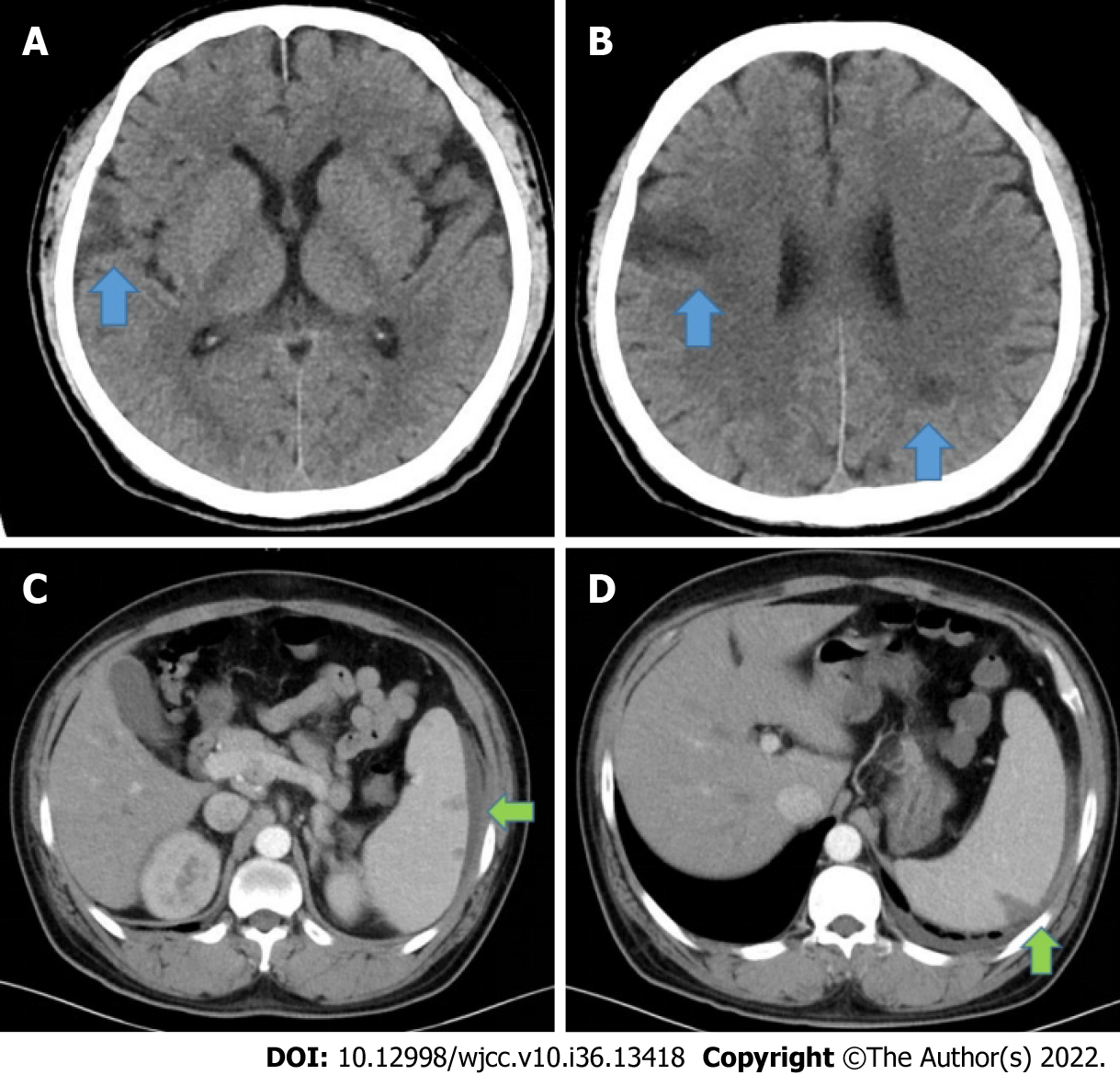

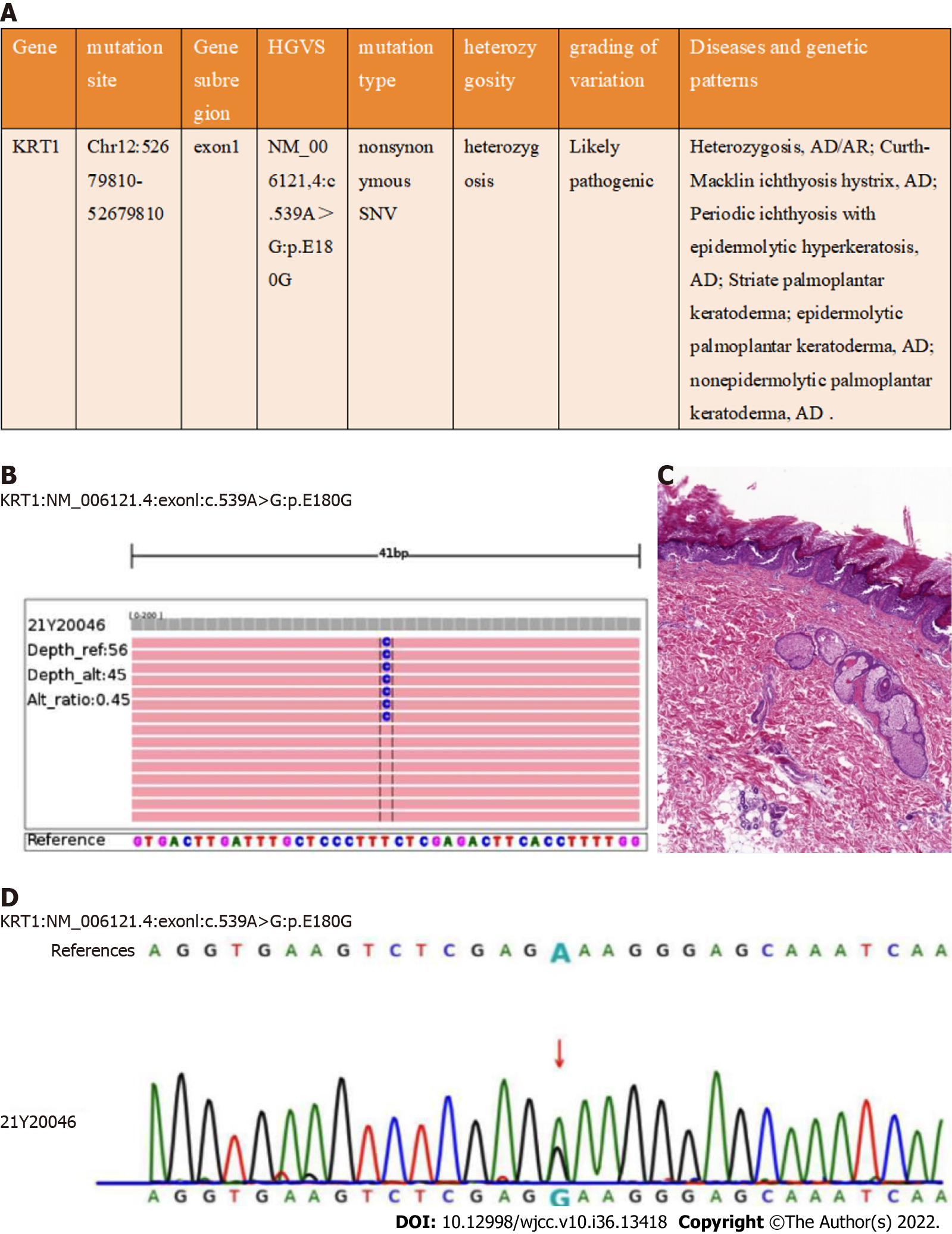

Cranial computed tomography revealed multiple low-density shadows in the brain (Figure 2). The computed tomography (CT) results of the chest were normal. Abdominal enhanced CT showed multiple low-density shadows in the spleen, which were considered to be splenic abscesses with subcapsular effusion (Figure 2). Given the persistent fever, bacteraemia, abscesses, and mitral valve insufficiency, we conducted transoesophageal echocardiography (Figure 3), which revealed a wart in the mitral valve with prolapse along with severe insufficiency. He was diagnosed with definitive infective endocarditis, clinically suspected to be attributable to his skin lesions. He was urgently referred to a dermatologist, who advised treatment with tretinoin, urea cream for external use, skin biopsy (Figure 4), and genetic tests. Later, a pathological examination was conducted on his skin, which showed epidermal hyperkeratosis, acantholysis, and lymphocytes infiltrating the superficial dermis around the blood vessels and adjuncts. Genetic tests revealed mutations in the keratin 1 (KRT1) gene (Figure 4).

The final diagnosis of the presented case was EHK combined with infectious endocarditis (IE).

He was started on intravenous 0.5 g levofloxacin once a day (QD). Four days later, levofloxacin was escalated to vancomycin 500 mg Q12 h due to a positive blood culture for Gram-positive coccal bacteraemia and persistent fever. When infective endocarditis and brain abscesses are diagnosed, the selection of antibiotics depends on drug sensitivity experiments; based on the results, his treatment was changed to 2 g ceftriaxone QD.

Cardiac surgery was planned for approximately 6-8 wk after completion of the course of antibiotics. Because of the use of antibiotics, his white cell counts and C-reactive protein levels remained within the normal range. Subsequent echocardiograms still showed a wart in the mitral valve with prolapse and severe insufficiency, but the valve excrescences appeared to be getting smaller. CT of the chest was repeated, which revealed a small pleural effusion. Cranial CT was also repeated, which indicated shrinking lesions. Blood cultures were repeated and were negative, and he remained apyrexial. Because of his medical insurance policy, the patient decided to return to his local hospital for further treatment.

The clinical manifestations, histopathological findings, and mutations in the KRT1 gene observed in this patient were consistent with the diagnostic criteria of EHK[3,4], a rare genodermatosis with autosomal-dominant inheritance[5]. EHK is associated with erythema, blistering, erosions and skin denudation present at birth, and develop marked hyperkeratosis in adult. The KRT1 mutation c.539A>G: p. E180G was found; this has been reported previously[6].

Patients with skin diseases often exhibit a disturbed skin barrier and tend to have poor cell-mediated immunity, such as atopic dermatitis, irritant contact dermatitis, ichthyosis, rosacea, and acne[7,8]. Patients with EHK, especially with subtypes of ichthyosis, are prone to repeated episodes of skin infections, including bacterial infection and fungal infection, but the mechanism is still elusive[4,9]. Several factors have been proposed, including disruption of skin barrier function, hyperkeratotic plaques and defective cell-mediated immunity[10-12]. Staphylococcus aureus is a leading cause of human bacterial infection, and the most common site of Staphylococcus aureus infection is the skin[13]. Skin and soft tissue infections with Staphylococcus remain a dominant cause of bacteraemia and IE[14,15].

The definition of SAB is as presence of ≥ 1 positive blood cultures for Staphylococcus aureus[16]. The most frequent site is the anterior nares, but the skin, axilla, oropharynx, perineum, and vagina may also be colonized. These colonized sites may serve as reservoirs for future infections. Colonization is relatively higher among patients with insulin-dependent diabetes, skin damage, HIV infection, and in patients undergoing maintenance haemodialysis[16]. SAB can lead to seeding and invasion of virtually any body site and associated complications[17]. The case fatality rates for SAB have only slightly improved in recent decades[18]. Patients with SAB can develop all kinds of complications, such as IE, epidural abscess, vertebral osteomyelitis, brain abscess, and discitis, which may be difficult to identify and can lead to high rates of disability and mortality[17,19].

SAB is a leading cause of bacteraemia and infective endocarditis. Only a minority of bacteraemic patients will show involvement of the heart valves. The frequency of endocarditis among SAB patients ranges from 5% to 10%-12%[20]. IE is a severe complication in patients with nosocomial SAB. It has a low incidence but high mortality. Therefore, prevention and early detection of IE are important. The incidence is highest in those with a previous history of IE or who have prosthetic, repaired valves, intravenous drug use or rheumatic heart disease[21,22]. Our patient had no history of these risk factors except EHK.

A case of atopic dermatitis, IE and multiple cerebral infarctions has been reported[23], but there are no previous reports of EHK and IE, such as in our case. Some factors have been speculated to increase the risk of infection, such as including disruption of skin barrier integrity, defective cell-mediated immunity, and delayed keratin scaling. In our case, a breached skin barrier secondary to EHK, coupled with inadequate skin sanitation, likely provided the opportunity for bacterial seeding by MSSA, triggering IE and abscesses. EHK may be associated with skin infection and multiple risk factors for extracutaneous infections. Patients with EHK should be treated early to minimize the consequences. If patients with EHK present with prolonged fever, IE and organ abscesses should be suspected or checked, including metastatic spreads. In conclusion, we highlight that in the absence of thorough treatment, clinicians should recognize that patients with EHK are susceptible to bacterial infections owing to disruption of the skin barrier.

We would like to thank the patient and his family. We extend our thanks to the dermatology, echocardiography, radiology, and pathology departments of the Beijing Tsinghua Changgung Hospital for facilitating the acquisition of the relevant materials.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Emergency medicine

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Ghimire R, Nepal; Nakaji K, Japan S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Miao H, Dong R, Zhang S, Yang L, Liu Y, Wang T. Inherited ichthyosis and fungal infection: an update on pathogenesis and treatment strategies. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2021;19:341-350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Rice AS, Crane JS. Epidermolytic Hyperkeratosis. [Updated 2022 Aug 1]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK544323/. |

| 3. | Kurosawa M, Takagi A, Tamakoshi A, Kawamura T, Inaba Y, Yokoyama K, Kitajima Y, Aoyama Y, Iwatsuki K, Ikeda S. Epidemiology and clinical characteristics of bullous congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma (keratinolytic ichthyosis) in Japan: results from a nationwide survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:278-283. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Peter Rout D, Nair A, Gupta A, Kumar P. Epidermolytic hyperkeratosis: clinical update. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2019;12:333-344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Hayashida MT, Mitsui GL, Reis NI, Fantinato G, Jordão Neto D, Mercante AM. Epidermolytic Hyperkeratosis--case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:888-891. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sashikawa M, Tsuda H, Komine M, Ohtsuki M. Novel missense mutation c.539A>G; p.Glu180Gly in keratin 1 causing epidermolytic ichthyosis. J Dermatol. 2021;48:e579-e580. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Proksch E. pH in nature, humans and skin. J Dermatol. 2018;45:1044-1052. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 166] [Cited by in RCA: 303] [Article Influence: 43.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Takahashi M, Hagiya H, Tanaka S, Yamamoto K, Honda H, Hasegawa K, Otsuka F. Persistent methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia in an adult patient with Netherton's syndrome: A case report. J Infect Chemother. 2022;28:978-981. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | DiGiovanna JJ, Bale SJ. Clinical heterogeneity in epidermolytic hyperkeratosis. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1026-1035. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Vyas NS, Kannan S, N Jahnke M, Hu RH, Choate KA, Shwayder TA. Congenital Ichthyosiform Erythroderma Superimposed with Chronic Dermatophytosis: A Report of Three Siblings. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33:e6-e9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hoetzenecker W, Schanz S, Schaller M, Fierlbeck G. Generalized tinea corporis due to Trichophyton rubrum in ichthyosis vulgaris. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:1129-1131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Schmuth M, Yosipovitch G, Williams ML, Weber F, Hintner H, Ortiz-Urda S, Rappersberger K, Crumrine D, Feingold KR, Elias PM. Pathogenesis of the permeability barrier abnormality in epidermolytic hyperkeratosis. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;117:837-847. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Becker RE, Bubeck Wardenburg J. Staphylococcus aureus and the skin: a longstanding and complex interaction. Skinmed. 2015;13:111-9; quiz 120. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Al-Bayati A, Alshami A, AlAzzawi M, Al Hillan A, Hossain M. Metastatic Osteoarticular Infective Endocarditis by Methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus Aureus. Cureus. 2020;12:e8124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Salvador VB, Chapagain B, Joshi A, Brennessel DJ. Clinical Risk Factors for Infective Endocarditis in Staphylococcus aureus Bacteremia. Tex Heart Inst J. 2017;44:10-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Rongpharpi SR, Duggal S, Kalita H, Duggal AK. Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: targeting the source. Postgrad Med. 2014;126:167-175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Keynan Y, Rubinstein E. Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia, risk factors, complications, and management. Crit Care Clin. 2013;29:547-562. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Holland TL, Arnold C, Fowler VG Jr. Clinical management of Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: a review. JAMA. 2014;312:1330-1341. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 294] [Cited by in RCA: 336] [Article Influence: 30.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Veronese C, Pellegrini M, Maiolo C, Morara M, Armstrong GW, Ciardella AP. Multimodal ophthalmic imaging of staphylococcus aureus bacteremia associated with chorioretinitis, endocarditis, and multifocal brain abscesses. Am J Ophthalmol Case Rep. 2020;17:100577. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kern WV. Management of Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia and endocarditis: progresses and challenges. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2010;23:346-358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Thornhill MH, Jones S, Prendergast B, Baddour LM, Chambers JB, Lockhart PB, Dayer MJ. Quantifying infective endocarditis risk in patients with predisposing cardiac conditions. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:586-595. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 19.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Cahill TJ, Prendergast BD. Infective endocarditis. Lancet. 2016;387:882-893. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 522] [Cited by in RCA: 656] [Article Influence: 72.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Furumura Y, Nishida M, Imanishi A, Maekawa N, Fukai K. Infectious endocarditis with multiple cerebral infarctions in a patient with severe atopic dermatitis. J Dermatol. 2019;46:e353-e354. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |