Published online Dec 26, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i36.13250

Peer-review started: August 12, 2022

First decision: September 4, 2022

Revised: September 15, 2022

Accepted: November 25, 2022

Article in press: November 25, 2022

Published online: December 26, 2022

Processing time: 136 Days and 8.6 Hours

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common type of liver cancer and has a high risk of invasion and metastasis along with a poor prognosis.

To investigate the independent predictive markers for disease-free survival (DFS) in patients with HCC and establish a trustworthy nomogram.

In this study, 445 patients who were hospitalized in The First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical College between December 2009 and December 2014 were retrospectively examined. The survival curve was plotted using the Kaplan–Meier method and survival was determined using the log-rank test. To identify the prognostic variables, multivariate Cox regression analyses were carried out. To predict the DFS in patients with HCC, a nomogram was created. C-indices and receiver operator characteristic curves were used to evaluate the nomogram's performance. Decision curve analysis (DCA) was used to evaluate the clinical application value of the nomogram.

Longer DFS was observed in patients with the following characteristics: elderly, I–II stage, and no history of hepatitis B. The calibration curve showed that this nomogram was reliable and had a higher area under the curve value than the tumor node metastasis (TNM) stage. Moreover, the DCA curve revealed that the nomogram had good clinical applicability in predicting 3- and 5-year DFS in HCC patients after surgery.

Age, TNM stage, and history of hepatitis B infection were independent factors for DFS in HCC patients, and a novel nomogram for DFS of HCC patients was created and validated.

Core Tip: In this study, age, tumor node metastasis (TNM) stage, and hepatitis B history were shown to be independent predictors of disease-free survival (DFS) in individuals with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Additionally, we developed and validated a new nomogram for estimating 3- and 5-year DFS in HCC patients. The calibration curves of the nomogram were reliable, and the new nomogram had a higher area under the curve value than the TNM stage. We believe that our findings will be of interest to the readers of the World Journal of Clinical Cases.

- Citation: Luo PQ, Ye ZH, Zhang LX, Song ED, Wei ZJ, Xu AM, Lu Z. Prognostic factors for disease-free survival in postoperative patients with hepatocellular carcinoma and construction of a nomogram model. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(36): 13250-13263

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i36/13250.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i36.13250

Many individuals with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) pass away each year worldwide, making it the fourth most prevalent cancer-related cause of death[1,2]. Considerable improvements in examination and treatment methods have increased the 5-year survival rate of patients with early stage liver cancer to 70% after radical resection[3]. However, the majority of HCC patients reach the middle or late stages when they are treated, and their 5-year survival rate is around 15%[4].

The pathogenesis of HCC is controversial and complicated[5], and viral hepatitis has been linked to liver cancer incidence[6]. Radical hepatectomy is the first route for HCC patients, and chemotherapy is administered as required according to the postoperative pathological results[7]. Clinical investigations have indicated that age, differentiation degree, hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) level, tumor size, alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) level, tumor node metastasis (TNM) stage, tumor number, gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT) level, and other factors are important prognostic factors for HCC[8-11]. According to Zheng et al[12], who noted that the neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio, and platelet-lymphocyte ratio represent new prognostic markers for HCC outcomes. Microvascular invasion, number of cancer nodules, margin positive and Child-Pugh status were discovered by Goh et al[13] to be independent predictors of overall survival (OS). Furthermore, research has demonstrated that GGT and aspartate aminotransferase/alanine aminotransferase levels are prognostic factors for OS of HCC patients[14]. However, there has been little research on disease-free survival (DFS) indicators in HCC patients. Therefore, this study aimed to identify clinical indicators that determine DFS in HCC patients.

The First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University treated 445 HCC patients with curative hepatectomy as part of this study's retrospective evaluation. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Histopathological confirmation of HCC; (2) R0 resection of liver cancer; (3) Availability of comprehensive clinical information; (4) Follow-up data were available; and (5) Absence of any further therapies, such as chemoradiotherapy and interventional therapy, ahead of surgery. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Postoperative pathology revealed cholangiocarcinoma or metastatic liver cancer; (2) Inadequate data were provided; (3) Child–Pugh grade C; and (4) An inability to keep up with follow-up appointments. Based on the threshold for each indicator in the blood, patients were divided into high and low groups. The median negative likelihood ratio (NLR) and positive likelihood ratio (PLR) were used as cut-off values. All patients submitted written informed permission for this study, which was authorized by the First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University's ethics committee.

Calls and outpatient visits were used to gather patient follow-up data. Subsequent examinations were carried out at fixed intervals (follow-up began one week after discharge and occurred every 4 mo after the first year). According to the inclusion criteria, we included a total of 445 postoperative HCC patients and excluded 14 patients who were lost to follow-up and 73 who were excluded. Finally, a cohort of 358 patients was analyzed.

SPSS software (version 19.0) was used to statistically evaluate all patient data. Categorical variables were investigated using Fisher's exact test or the chi-squared test. DFS was analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier method, and verified by the log-rank test. An elevated risk of mortality was indicated by a hazard ratio (HR) >1.0. The R Project (3.5.5) was used to create the nomogram.

344 HCC patients were enrolled in this study (Table 1). The patients were divided into two groups: Elderly (aged ≥ 70 years) and young (aged < 70 years). Patients with a history of hepatitis B accounted for 25% of the total. 256 individuals had cirrhosis, while the majority of the 88 patients who did not have cirrhosis had abnormal liver function, such fatty liver disease. The median NLR and PLR were 2.19 and 97.67, respectively. The average follow-up period was 52 mo. HCC patients had 1-, 3-, and 5-year DFS rates of 73.26%, 59.30%, and 44.48%, respectively.

| Characteristics | Median (25th–75th percentile) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 279 (81.10) |

| Female | 65 (18.90) |

| Age (yr) | |

| ≥ 70 | 46 (13.37) |

| < 70 | 298 (86.63) |

| Smoking history | |

| Yes | 151 (43.90) |

| No | 193 (56.10) |

| Alcohol consumption history | |

| Yes | 133 (38.66) |

| No | 211 (61.34) |

| History of hepatitis B | |

| Yes | 86 (25.00) |

| No | 258 (75.00) |

| Hypertension | |

| Yes | 80 (23.26) |

| No | 264 (76.74) |

| Diabetes | |

| Yes | 41 (11.92) |

| No | 303 (88.08) |

| BMI | |

| < 18.5 | 26 (7.56) |

| ≥ 18.5, < 23 | 160 (46.51) |

| ≥ 23 | 158 (45.93) |

| Liver cirrhosis | |

| Yes | 256 (74.42) |

| No | 88 (25.58) |

| Ascites | |

| Yes | 44 (12.79) |

| No | 300 (87.21) |

| Cancer nodules | |

| Single | 299 (86.92) |

| Multiple | 45 (13.08) |

| Capsule | |

| Yes | 290 (84.30) |

| No | 54 (15.70) |

| Tumor diameter | |

| ≥ 5 cm | 163 (47.38) |

| < 5 cm | 181 (52.62) |

| Differentiation grade | |

| Low | 85 (24.71) |

| Moderate and High | 259 (75.29) |

| TNM stage | |

| I | 262 (76.16) |

| II | 38 (11.05) |

| III | 40 (11.63) |

| IV | 4 (1.16) |

| Portal vein thrombus | |

| Yes | 13 (3.78) |

| No | 331 (96.22) |

| HBsAg | |

| Positive | 268 (77.91) |

| Negative | 76 (22.09) |

| Surgical method | |

| Proximal stomach | 86 (25.00) |

| Full stomach | 258 (75.00) |

| 5-year survival | |

| Yes | 162 (47.09) |

| No | 182 (52.91) |

| Prothrombin time (s) | 13.80 (13.30-14.50) |

| Fibrinogen (g/L) | 2.91 (2.41-3.54) |

| ALB (g/L) | 40.45 (37.23-43.78) |

| TBIL (μmol/L) | 10.00 (8.00-15.00) |

| TC (mmol/L) | 4.35 (3.62-4.86) |

| ALT (U/L) | 34.50 (24.00-49.00) |

| AST (U/L) | 36.00 (27.00-52.00) |

| GGT (U/L) | 55.50 (34.00-122.75) |

| NLR | 2.19 (1.64-3.31) |

| PLR | 97.67 (72.10-138.17) |

Tables 2 and 3 show the results of univariate and multivariate regression analyses, respectively. Age, past hepatitis B infection history, and TNM stage were independent predictors of DFS in HCC patients. The HR was 0.543 for patients < 70 years and 0.654 among those who did not have a history of hepatitis B.

| Characteristics | HR value (95%CI) | P value |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Female | 0.840 (0.574, 1.230) | 0.371 |

| Age (yr) | ||

| < 70 | 1.00 (reference) | |

| ≥ 70 | 0.577 (0.350, 0.951) | 0.031a |

| Smoking history | ||

| No | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Yes | 1.031 (0.770, 1.381) | 0.839 |

| Alcohol use history | ||

| No | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Yes | 0.813 (0.601, 1.101) | 0.182 |

| History of hepatitis B | ||

| No | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Yes | 1.392 (1.008, 1.921) | 0.044a |

| Hypertension | ||

| Yes | 1.00 (reference) | |

| No | 0.684 (0.471, 0.993) | 0.046a |

| Diabetes | ||

| No | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Yes | 0.816 (0.513, 1.298) | 0.390 |

| BMI | ||

| ≥ 23 | 1.00 (reference) | |

| < 23 | 0.912 (0.682, 1.221) | 0.537 |

| Liver cirrhosis | ||

| No | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Yes | 1.321 (0.930, 1.876) | 0.120 |

| Ascites | ||

| No | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Yes | 1.172 (0.774, 1.776) | 0.453 |

| Cancer nodules | ||

| Single | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Multiple | 1.668 (1.140, 2.497) | 0.013a |

| Capsule | ||

| No | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Yes | 1.349 (0.925, 1.966) | 0.120 |

| Tumor diameter (cm) | ||

| < 5 | 1.00 (reference) | |

| ≥ 5 | 1.350 (1.010, 1.804) | 0.043a |

| Differentiation grade | 0.124 | |

| Moderate and High | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Low | 1.291 (0.932, 1.787) | 0.124 |

| TNM stage | ||

| I-II | 1.00 (reference) | |

| III-IV | 1.692 (1.224, 2.340) | 0.001a |

| Portal vein thrombus | ||

| No | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Yes | 2.862 (1.508, 5.432) | 0.001a |

| HBsAg | ||

| Negative | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Positive | 1.107 (0.774, 1.582) | 0.579 |

| AFP (ng/mL) | ||

| ≥ 400 | 1.00 (reference) | |

| < 400 | 0.958 (0.683, 1.345) | 0.805 |

| Fibrinogen (g/L) | ||

| ≤ 4 | 1.00 (reference) | |

| > 4 | 1.494 (1.037, 2.152) | 0.031a |

| Prothrombin time | ||

| Abnormal | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Normal | 0.836 (0.565, 1.236) | 0.369 |

| ALB (g/L) | ||

| < 40 | 1.00 (reference) | |

| ≥ 40 | 0.988 (0.746, 1.335) | 0.457 |

| TBIL (μmol/L) | ||

| ≤ 20.5 | 1.00 (reference) | |

| > 20.5 | 1.180 (0.762, 1.827) | 0.457 |

| TC (mmol/L) | ||

| ≤ 5.2 | 1.00 (reference) | |

| > 5.2 | 1.401 (0.980, 2.003) | 0.065 |

| ALT (U/L) | ||

| ≤ 50 | 1.00 (reference) | |

| > 50 | 1.049 (0.743, 1.481) | 0.786 |

| AST (U/L) | ||

| ≤ 40 | 1.00 (reference) | |

| > 40 | 1.055 (0.785, 1.416) | 0.724 |

| GTT (U/L) | ||

| ≤ 60 | 1.00 (reference) | |

| > 60 | 1.279 (0.957, 1.709) | 0.097 |

| NLR | 0.938 | |

| < 2.19 | 1.00 (reference) | |

| ≥ 2.19 | 0.988 (0.740, 1.321) | 0.938 |

| PLR | ||

| < 97.67 | 1.00 (reference) | |

| ≥ 97.67 | 0.956 (0.715, 1.277) | 0.759 |

| Characteristics | HR value (95%CI) | P value |

| Age (yr) | ||

| < 70 | 1.00 (reference) | |

| ≥ 70 | 0.543 (0.328, 0.898) | 0.017a |

| History of hepatitis B | ||

| Yes | 1.00 (reference) | |

| No | 0.654 (0.472, 0.907) | 0.011a |

| Hypertension | ||

| Yes | 1.00 (reference) | |

| No | 0.754 (0.510, 1.114) | 0.156 |

| Cancer nodules (Single/ Multiple) | ||

| Single | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Multiple | 1.009 (0.579, 1.757) | 0.975 |

| Tumor diameter (cm) | ||

| < 5 | 1.00 (reference) | |

| ≥ 5 | 1.125 (0.817, 1.548) | 0.471 |

| TNM stage | ||

| III-IV | 1.00 (reference) | |

| I-II | 0.585 (0.423, 0.810) | 0.001a |

| Portal vein thrombus | ||

| No | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Yes | 1.784 (0.885, 3.597) | 0.106 |

| Fibrinogen (> 4 g/L/≤ 4 g/L) | ||

| ≤ 4 g/L | 1.00 (reference) | |

| > 4 g/L | 1.304 (0.872, 1.951) | 0.196 |

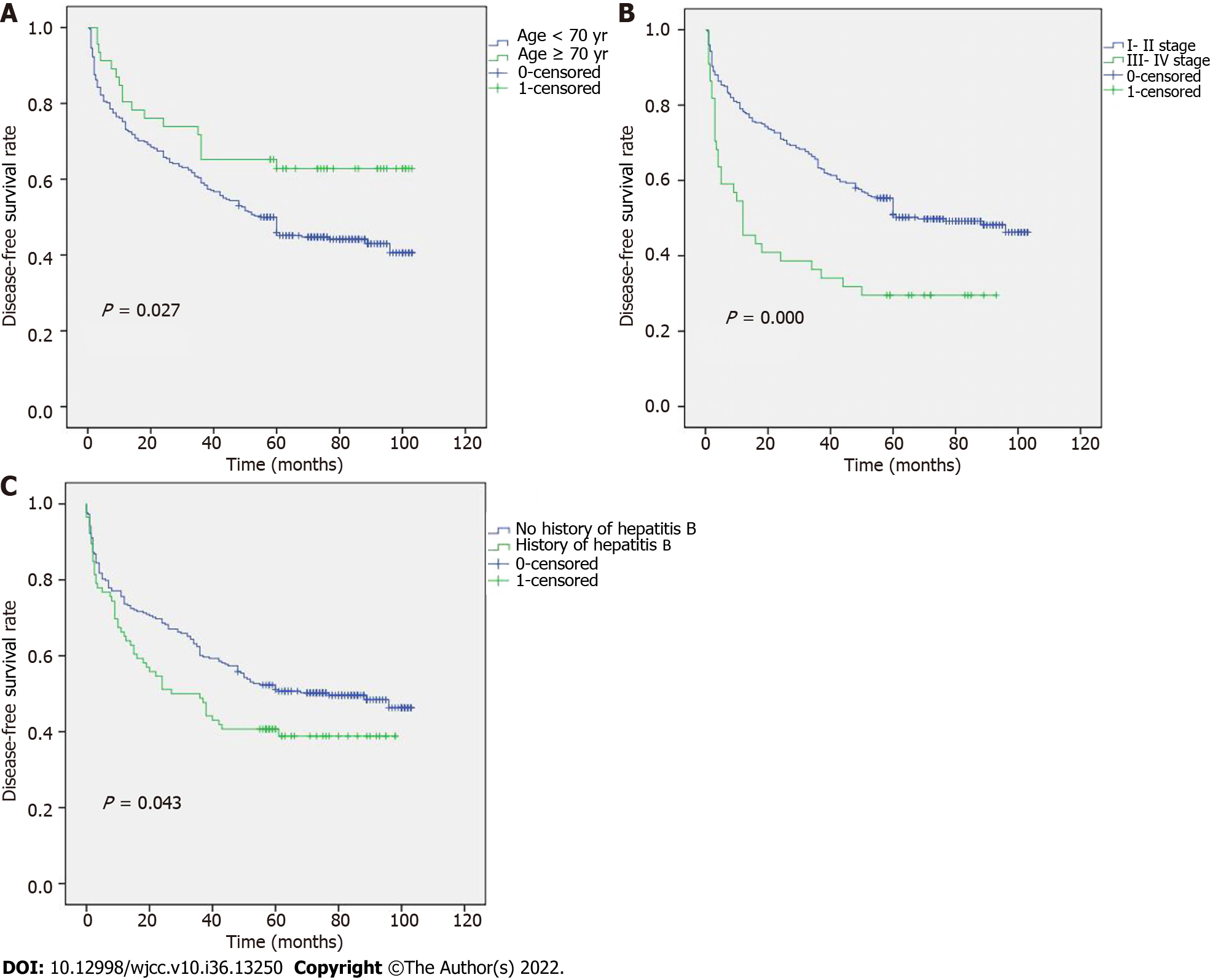

Young patients had a higher recurrence risk or mortality risk within 6 mo after surgery as a significant downhill trend was seen in these patients in the first 6 mo (Figure 1A). The DFS outcomes in patients who had different TNM stages and a history of hepatitis B are shown in Figures 1B and C, respectively. The median DFS for stages III–IV was 12 mo, and was 68 mo for stages I–II.

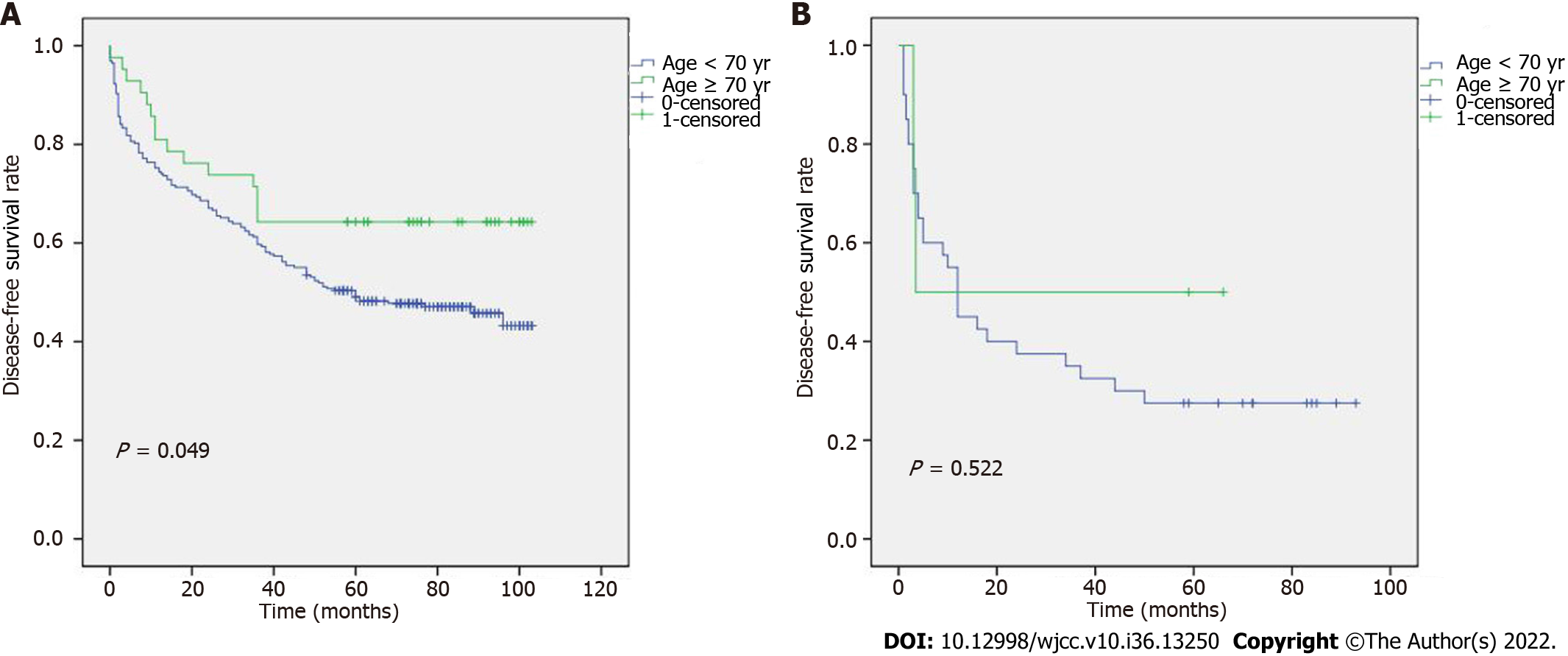

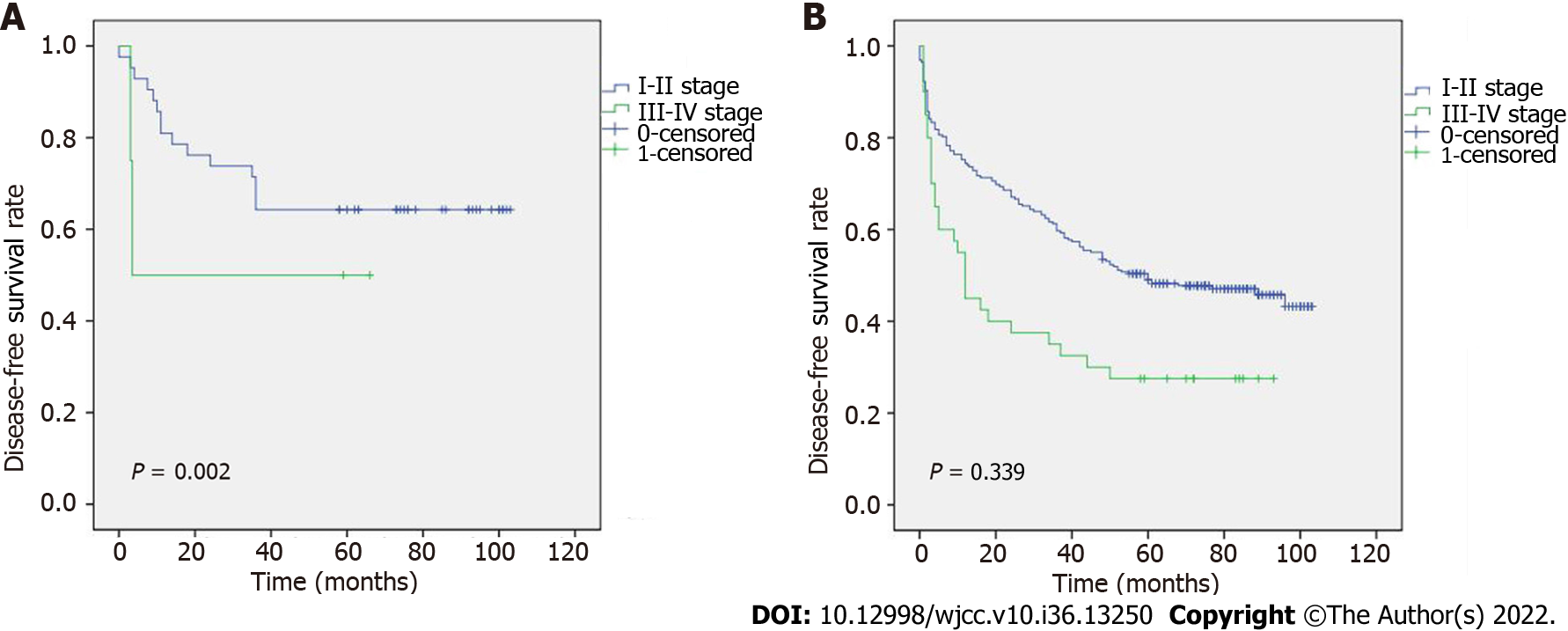

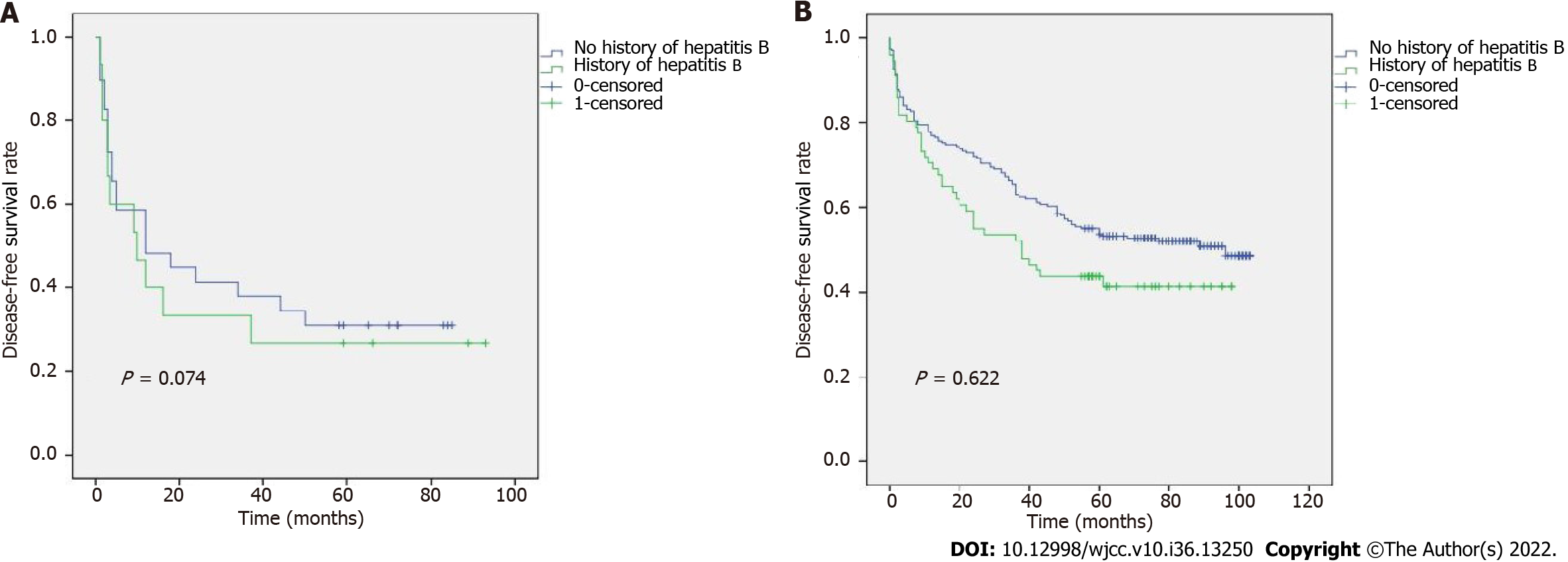

To determine the relationship between TNM stage and age, the DFS results are shown in Figure 2A and B. Figure 2A shows that, in stages I-II, patients ≥ 70 years had a longer DFS than those who were < 70 years. However, no discernible differences between stages III-IV were seen. In addition, we revealed an association between age and various TNM stages (Figure 3A and B). According to our results, individuals at stages I and II who were < 70 years had a better prognosis. The relationship between TNM stage and a history of hepatitis B was also examined (Figure 4A and B), but the difference was not statistically significant.

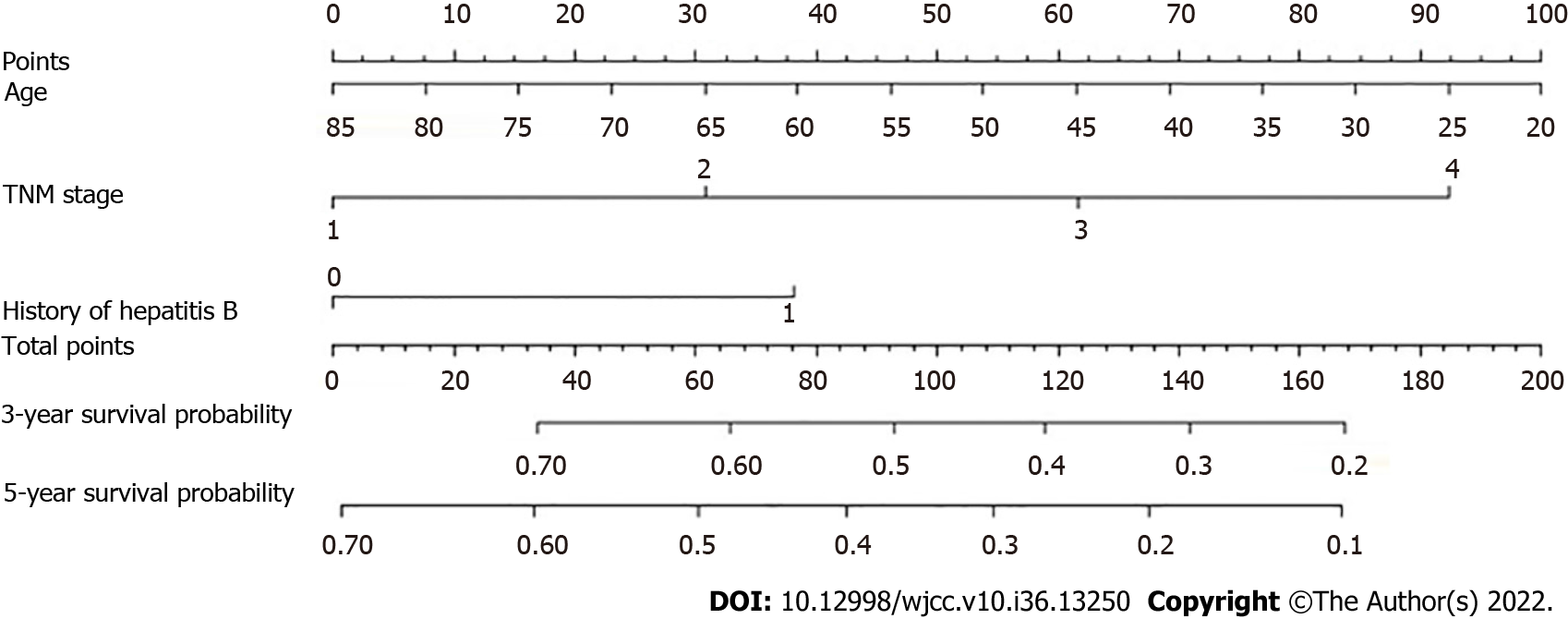

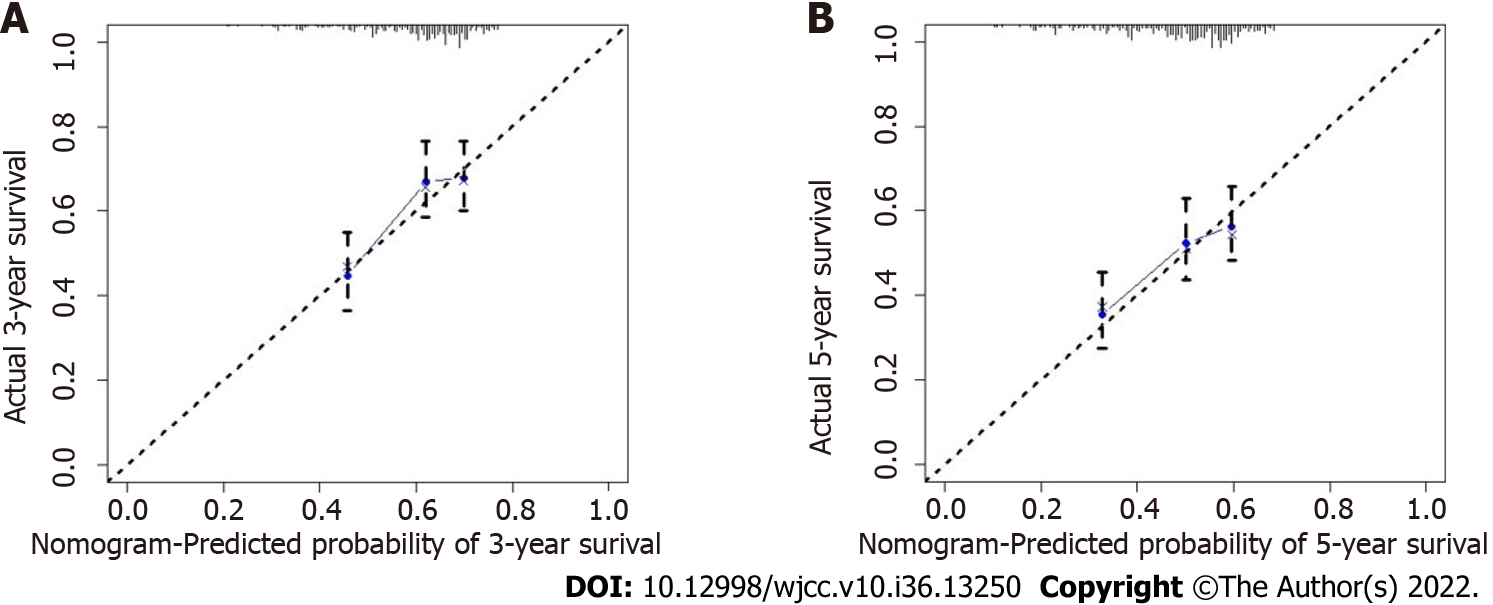

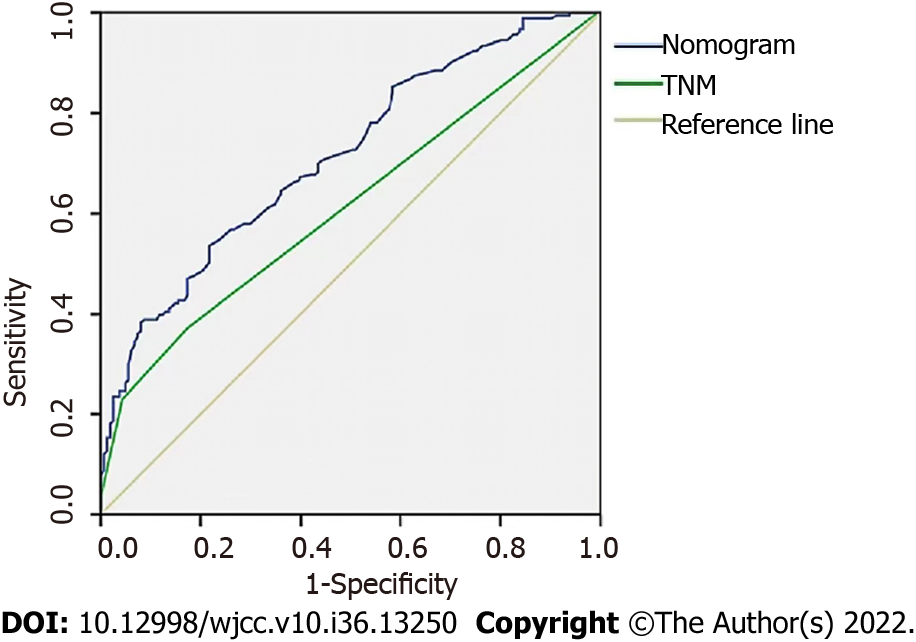

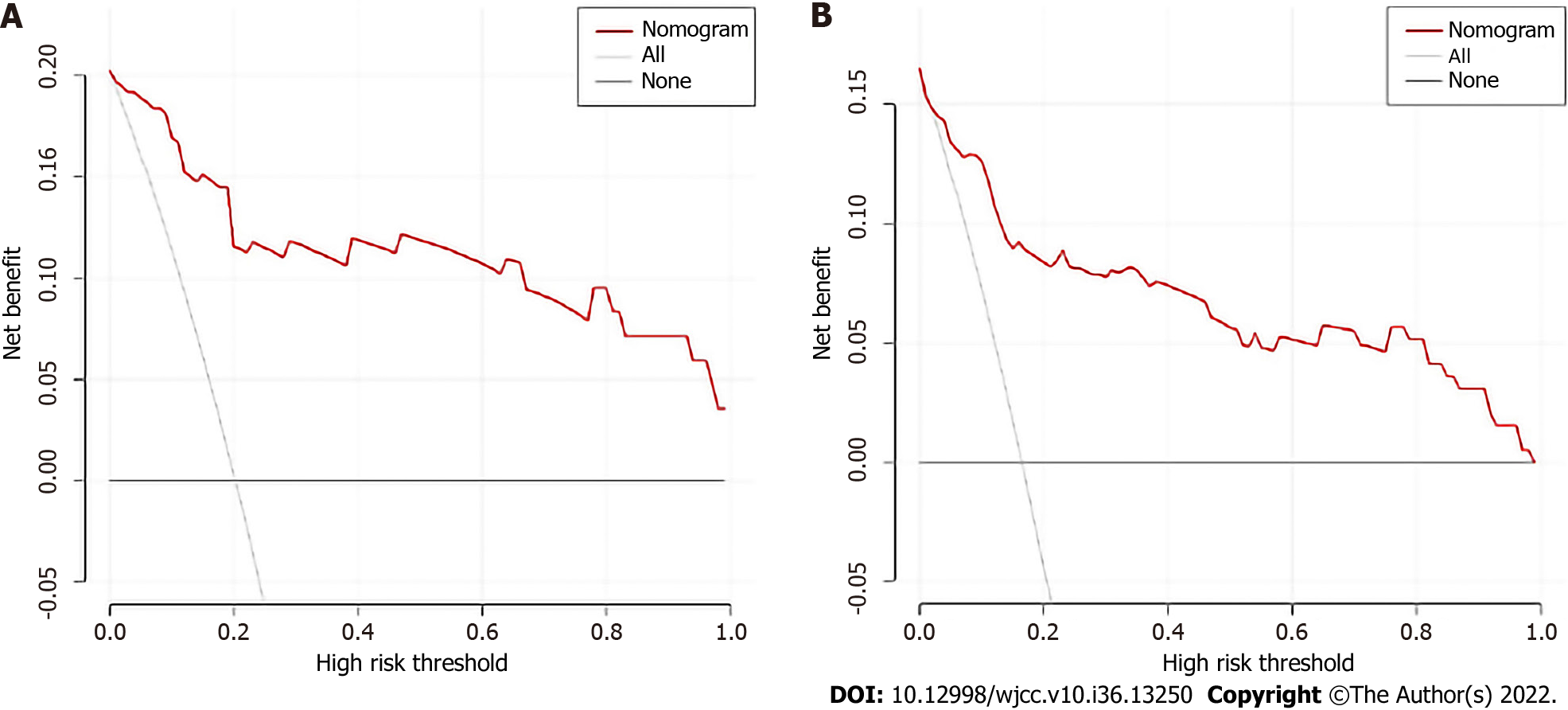

Age, TNM stage, and previous hepatitis B infection were utilized to create a nomogram (Figure 5). The C-index was calculated to be 0.713 (95%CI: 0.660–0.767) using 1000 bootstrap resampling methods, which indicated that the nomogram had a strong level of predictability. The actual survival curve of the nomogram matched closely, based on calibration curves for the 3- and 5-year DFS (Figure 6A and B). We compared the nomogram's receiver operator characteristic against that of the TNM stage to further assess the performance of the model and discovered that the nomogram's area under the curve was greater than that of the TNM stage (Figure 7). The nomogram enhanced the capacity to predict DFS in patients with HCC throughout a large range of risk threshold probabilities, according to the 3- and 5-year decision curve analysis curves (Figure 8A and B).

HCC has a high incidence and fatality rate, and increasing attention has been focused on HCC prognostic factors[15,16].

Recently, nomograms have been widely used as diagnostic and prognostic tools for various cancers[17]. We attempted to develop a prognostic nomogram that combines most of the important serum markers and clinicopathological characteristics. Many studies have shown that carbohydrate antigen 199 and AFP are related to the OS of patients with HCC[18,19], and the NLR and PLR levels found in the current investigation were similar to earlier results[20,21]. However, we discovered that hematological markers such as NLR, and AFP were not predictive of DFS.

Based on earlier published studies, the elderly group of HCC patients in our study was classified as those ≥ 70 years[22,23]. We examined the DFS of patients aged ≥ 70 and < 70 at TNM stages I-II and III-IV to further understand how age affects DFS in patients with various TNM stages. Sakakibara et al[24] used 40 years as the cutoff between young and elderly patients, and found that the 3-year OS of stage IIB patients in the young group was considerably lower than that of the elderly group, which is comparable to our results. Similar findings were obtained by Zhao et al[25], who retrospectively selected 995 colorectal cancer patients aged 35 years and discovered that they had a poorer prognosis. Faber et al[26], on the other hand, retrospectively examined 141 individuals and reported that those under the age of 35 often had a considerably better prognosis. Regardless of age, we discovered that stages I and II had a more favorable survival than stages III and IV, which is in line with the results of Lu Wu et al[27].

Hepatitis B virus (HBV), which affects 30% of people globally and is particularly widespread in China[28], is the main culprit in HCC. According to Li et al[29], preoperative HBV DNA levels over 2000 IU/mL were associated with a poorer prognosis and were strongly correlated with OS and DFS. In terms of the pathogenesis of HCC brought on by HBV, the integration of HBV DNA into the host genome triggered changes in gene protrusions, leading to the occurrence of liver cancer. In contrast, HBV-associated proteins, such as HBsAg, hepatitis B core antigen, and HBx, can mediate oxidative stress in cells[30]. Hence, for patients with HCC, more attention should be paid to a history of HBV in clinical practice.

This study had certain limitations, including an insufficient number of elderly patients and was a single center study. A limited relationship was observed between hepatitis B and HCC in Western countries; therefore, this study failed to collect clinical information from more patients (including foreign patients) through the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results and other databases to develop a more comprehensive and convincing nomogram model.

Age, TNM stage, and a history of hepatitis B infection were independent predictive factors of DFS in HCC patients. We constructed and validated an accurate and reliable nomogram that has great reference value for evaluating the prognosis of patients and guiding treatment.

The most prevalent form of liver cancer is hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), which also has a poor prognosis and a serious risk of invasion and metastasis.

The First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University treated 445 HCC patients with curative hepatectomy.

The objective of this study was to develop a valid nomogram and explore the independent prognostic markers for disease-free survival (DFS) in HCC patients.

A survival curve was plotted using the Kaplan–Meier method and tested using the log-rank method. To identify the prognostic variables, multivariate Cox regression analysis was carried out. To predict DFS in patients with HCC, a nomogram was created. C-indices and receiver operator characteristic curves were used to evaluate the nomogram's performance. Decision curve analysis (DCA) was used to evaluate the clinical application value of the nomogram.

A longer DFS was observed in patients with the following characteristics: Elderly, I-II stage, and no history of hepatitis B. The calibration curve showed that this nomogram was reliable and had a higher area under the curve value than the tumor node metastasis stage. Moreover, the DCA curve revealed that the nomogram had good clinical applicability in predicting 3- and 5-year DFS in HCC patients after surgery.

We created and tested a new nomogram to predict DFS in HCC patients, which was accurate and reliable.

We constructed and validated an accurate and reliable nomogram that has great reference value for evaluating the prognosis of patients and guiding treatment.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Nath L, India; Soldera J, Brazil S-Editor: Liu GL L-Editor: Webster JR P-Editor: Liu GL

| 1. | Llovet JM, Kelley RK, Villanueva A, Singal AG, Pikarsky E, Roayaie S, Lencioni R, Koike K, Zucman-Rossi J, Finn RS. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021;7:6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1343] [Cited by in RCA: 3793] [Article Influence: 948.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 2. | Huang DQ, Singal AG, Kono Y, Tan DJH, El-Serag HB, Loomba R. Changing global epidemiology of liver cancer from 2010 to 2019: NASH is the fastest growing cause of liver cancer. Cell Metab 2022; 34: 969-977. e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 322] [Article Influence: 107.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2018;69:182-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5593] [Cited by in RCA: 5990] [Article Influence: 855.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 4. | Ilikhan SU, Bilici M, Sahin H, Akca AS, Can M, Oz II, Guven B, Buyukuysal MC, Ustundag Y. Assessment of the correlation between serum prolidase and alpha-fetoprotein levels in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol.. 2015;21:6999-7007. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Fransvea E, Paradiso A, Antonaci S, Giannelli G. HCC heterogeneity: molecular pathogenesis and clinical implications. Cell Oncol.. 2009;31:227-233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Maucort-Boulch D, de Martel C, Franceschi S, Plummer M. Fraction and incidence of liver cancer attributable to hepatitis B and C viruses worldwide. Int J Cancer. 2018;142:2471-2477. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 200] [Cited by in RCA: 227] [Article Influence: 32.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Schlachterman A, Craft WW Jr, Hilgenfeldt E, Mitra A, Cabrera R. Current and future treatments for hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:8478-8491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Bucci L, Garuti F, Camelli V et al. Italian liver cancer (ITA.LI.CA) Comparison between alcohol- and hepatitis C virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma: clinical presentation, treatment and outcome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 43:385-399. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hu Y, You S, Yang Z, Cheng S. Nomogram predicting survival of hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein tumour thrombus after curative resection. ANZ journal of surgery. 2019;89 (1-2):E20-e25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Xu Y, Yuan X, Zhang X, Hu W, Wang Z, Yao L, Zong L. Prognostic value of inflammatory and nutritional markers for hepatocellular carcinoma. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100:e26506. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Zhang H, Yu X, Xu J, Li J, Zhou Y. Combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma: An analysis of clinicopathological characteristics after surgery. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98:e17102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Zheng J, Cai J, Li H, Zeng K, He L, Fu H, Zhang J, Chen L, Yao J, Zhang Y, Yang Y. Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio and platelet to lymphocyte ratio as prognostic predictors for hepatocellular carcinoma patients with various treatments: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Cell Physiol Biochem. 44:967-981. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 186] [Article Influence: 23.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Goh BK, Chow PK, Teo JY, Wong JS, Chan CY, Cheow PC, Chung AY, Ooi LL. Number of nodules, Child-Pugh status, margin positivity, and microvascular invasion, but not tumor size, are prognostic factors of survival after liver resection for multifocal hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2014;18:1477-1485. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Zhang LX, Lv Y, Xu AM, Wang HZ. The prognostic significance of serum gamma-glutamyltransferase levels and AST/ALT in primary hepatic carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2019;19:841. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Cheon J, Yoo C, Hong JY, Kim HS, Lee DW, Lee MA, Kim JW, Kim I, Oh SB, Hwang JE, Chon HJ, Lim HY. Efficacy and safety of atezolizumab plus bevacizumab in Korean patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Int. 42:674-681. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 14.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Pinter M, Scheiner B, Peck-Radosavljevic M. Immunotherapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a focus on special subgroups. Gut. 2021;70:204-214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 42.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. |

Ohori Tatsuo G, Riu Hamada M, Gondo T, Hamada R: Nomogram as predictive model in clinical practice.

|

| 18. | Chan MY, She WH, Dai WC, Tsang SHY, Chok KSH, Chan ACY, Fung J, Lo CM, Cheung TT. Prognostic value of preoperative alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) level in patients receiving curative hepatectomy- an analysis of 1,182 patients in Hong Kong. Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;4:52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Dai T, Peng L, Lin G, Li Y, Yao J, Deng Y, Li H, Wang G, Liu W, Yang Y, Chen G. Preoperative elevated plasma fibrinogen level predicts tumor recurrence and poor prognosis in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2019;10:1049-1063. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Johnson PJ, Dhanaraj S, Berhane S, Bonnett L, Ma YT. The prognostic and diagnostic significance of the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in hepatocellular carcinoma: a prospective controlled study. Br J Cancer.. 2021;125:714-716. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Mahassadi AK, Anzouan-Kacou Kissi H, Attia AK. The prognostic values of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio at baseline in predicting the in-hospital mortality in Black African patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma in palliative treatment: a comparative cohort study. Hepat Med.. 2021;13:123-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Cucchetti A, Sposito C, Pinna AD, Citterio D, Ercolani G, Flores M, Cescon M, Mazzaferro V. Effect of age on survival in patients undergoing resection of hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Surg.. 2016;103:e93-e99. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Hsu KF, Yu JC, Yang CW, Chen BC, Chen CJ, Chan DC, Fan HL, Chen TW, Shih YL, Hsieh TY, Hsieh CB. Long-term outcomes in elderly patients with resectable large hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing hepatectomy. Surg Oncol.. 2018;27:595-601. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Sakakibara A, Matsui K, Katayama T, Higuchi T, Terakawa K, Konishi I. Age-related survival disparity in stage IB and IIB cervical cancer patients. J Obstet Gynaecol Res.. 2019;45:686-694. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Zhao L, Bao F, Yan J, Liu H, Li T, Chen H, Li G. Poor prognosis of young patients with colorectal cancer: a retrospective study. Int J Colorectal Dis.. 2017;32:1147-1156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Faber W, Stockmann M, Schirmer C, Möllerarnd A, Denecke T, Bahra M, Klein F, Schott E, Neuhaus P, Seehofer D. Significant impact of patient age on outcome after liver resection for HCC in cirrhosis. Eur J Surg Oncol.. 2014;40:208-213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Wu L, Tsilimigras DI, Farooq A, Hyer JM, Merath K, Paredes AZ, Mehta R, Sahara K, Shen F, Pawlik TM. Management and outcomes among patients with sarcomatoid hepatocellular carcinoma: A population-based analysis. Cancer. 2019;125:3767-3775. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Cui F, Shen L, Li L, Wang H, Wang F, Bi S, Liu J, Zhang G, Zheng H, Sun X, Miao N, Yin Z, Feng Z, Liang X, Wang Y. Prevention of chronic hepatitis B after 3 decades of escalating vaccination policy, China. Emerg Infect Dis.. 2017;23:765-772. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 176] [Cited by in RCA: 261] [Article Influence: 32.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Li L, Li B, Zhang M. HBV DNA levels impact the prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma patients with microvascular invasion. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98:e16308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Levrero M, Zucman-Rossi J. Mechanisms of HBV-induced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol.. 2016;64:S84-S101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 479] [Cited by in RCA: 703] [Article Influence: 78.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |