INTRODUCTION

General information on amebic liver abscess

Worldwide the most commonly encountered manifestation of invasive extraintestinal amebiasis in humans is amebic liver abscesses (ALAs), which occur when Entamoeba histolytica (E. histolytica) spreads extraintestinally[1-5]. In 9% of cases, liver abscesses develop as a complication of amebiasis, and in 2010, ALAs led to a total of nearly 50000 fatalities[6,7]. Though cases have declined in number in recent years, ALAs are still a major public health issue within endemic areas[8]. ALA patients may present with what appears to be colitis, with pain in the upper right abdomen and sometimes accompanied by a fever; however, asymptomatic infections may also occur[1,9]. Hepatitis E virus infection and amebiasis are endemic in India and coexisting acute hepatitis E and ALA has also been reported[10]. The aim of this review was to share the general information of ALA and its pathogenesis, examinations, diagnosis, treatment, complications, prognosis, and prevention.

General information on amebiasis

E. histolytica is an anaerobic parasitic invasive enteric protozoan, and infections of E. histolytica correlate to high mortality and morbidity rates[11,12]. Each year, this protozoan causes 40000-100000 deaths, ranking only behind malaria in patient mortality[13-15]. According to a previous report, invasive amebiasis develops in fewer than one-tenth of patient infections[11]. The geographic distribution of amebiasis has worldwide amplitude and a high rate of incidence, and it remains a public health concern in low- and middle-income developing countries in the tropics, particularly in environments that are crowded and lacking in adequate sanitation and clean water due to the oral-fecal route of pathogen transmission (including ingestion of food or water that contains cysts from this protozoan)[6,16-19]. On the other hand, this pathogen is only rarely seen in wealthier countries but is epidemiologically growing; in particular, recent immigrants from endemic regions (or travelers returning from a long-term stay in an endemic region) have a greater risk of developing amebiasis[6,20-22].

Maintaining a high index of suspicion is recommended for amebiasis regarding other groups that are at greater risk, such as men who have sex with men, people with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome or HIV, immunocompromised hosts such as patients with cirrhosis, or people who reside in group homes or mental health facilities[6,23]. In particular, relatively large numbers of cases have been reported in Japan in individuals infected with HIV-1, and it was found that these individuals commonly suffered from subclinical amebiasis[24]. In addition, asymptomatic individuals infected with HIV-1 who have a high anti-E. histolytica titer run a risk of invasive amebiasis, most likely as a result of subclinical amebiasis exacerbation[24].

In the Western world, the low overall prevalence, as well as the fact that the latency period between infection by the underlying pathogen and clinical symptom onset may be lengthy, creates a risk of delaying diagnosis of amebiasis and thus inadequate treatment[20]. Additionally, pregnancy has also been found to be an invasive amebiasis risk factor; management of pregnant patients becomes especially complex[20]. Mortality due to amebiasis is primarily the result of extraintestinal infections, with the most common of these being ALAs[25].

PATHOGENESIS

The route of transmission of E. histolytica that leads to ALA has yet to be thoroughly elucidated; broadly, after E. histolytica breaches the host’s innate defenses, it causes liver abscess and amebic colitis by invading the intestinal mucosa[8,26]. Often, trophozoites enter the circulatory system. They are then filtered in the liver and produce abscesses and can develop further into severe invasive diseases, such as ALAs[27]. On the other hand, conditions of immune-compromised individuals and/or momentaneous immune modulation in humans have been reported to increase both bacterial and viral activities/ infections and related diseases[28-31]. ALA may arise following an impairment of the anti-E. histolytica immune system, and the immune evasion is a typical mode of action of pathogens in humans.

Regarding its molecular mechanism, E. histolytica uses the virulence factor Gal/GalNAc lectin in order to invade the host tissue; this molecule not only protects against ALAs but also induces an adherence-inhibitory antibody response[3]. In addition, E. histolytica has a pair of low-molecular-weight protein tyrosine phosphatase (LMW-PTP) genes, EhLMW-PTP1 and EhLMW-PTP2, which are expressed through cysts, cultured trophozoites, and clinical isolates[32]. There is a single amino acid sequence difference, at position A85V, between the proteins EhLMW-PTP1 and EhLMW-PTP2[32]. Both of these genes are expressed in cultured trophozoites, particularly EhLMW-PTP2; trophozoites that are recovered from ALAs show downregulated EhLMW-PTP1 expression[32].

In an in vitro study, the compound linearolactone, as isolated from Salvia polystachya, demonstrated antiparasitic activity against E. histolytica through the production of reactive oxygen species and was able to induce apoptosis-like effects in trophozoites of E. histolytica through intracellular reactive oxygen species production, which affected the structure of the actin cytoskeleton[33]. Therefore, linearolactone served to more actively reduce ALA development[33]. Furthermore, calreticulin is a highly conserved protein in the endoplasmic reticulum and serves in an important capacity in regulating vital cellular functions[34]. In patients with acute phase ALAs, interleukin levels (interleukin-6, interleukin-10, granulocyte colony stimulating factor, and transforming growth factor β1) were higher, while resolution phase ALA patients had higher levels of interferon gamma detected[34].

Entamoeba dispar is a separate amoeba species that annually infects 12% of the global population, and it has been classified as “noninvasive” in the past[17]. However, this amoeba has been isolated from patients suffering from symptomatic non-dysenteric colitis, and DNA sequences from this species have been both detected and genotyped in samples from dysenteric colitis patients as well as samples from ALA patients, suggesting that this amoeba may play some role in human large intestine and liver lesion development[17].

EXAMINATIONS

It is difficult to distinguish ALA from pyogenic liver abscesses using only clinical, laboratory, and radiological findings[35,36]. In order to diagnose the various ALA-related complications, computed tomography (CT) scans serve as an ideal tool[37]. As a result, serologic E. histolytica tests are a necessary part of accurate evaluations of liver abscesses within high-risk groups[35,36]. On the other hand, in a study to use CT findings to determine different morphological types of ALA and to determine any differences in their clinical features, ALAs were found to have three distinct CT morphological types, each varying in terms of its laboratory and clinical features[38].

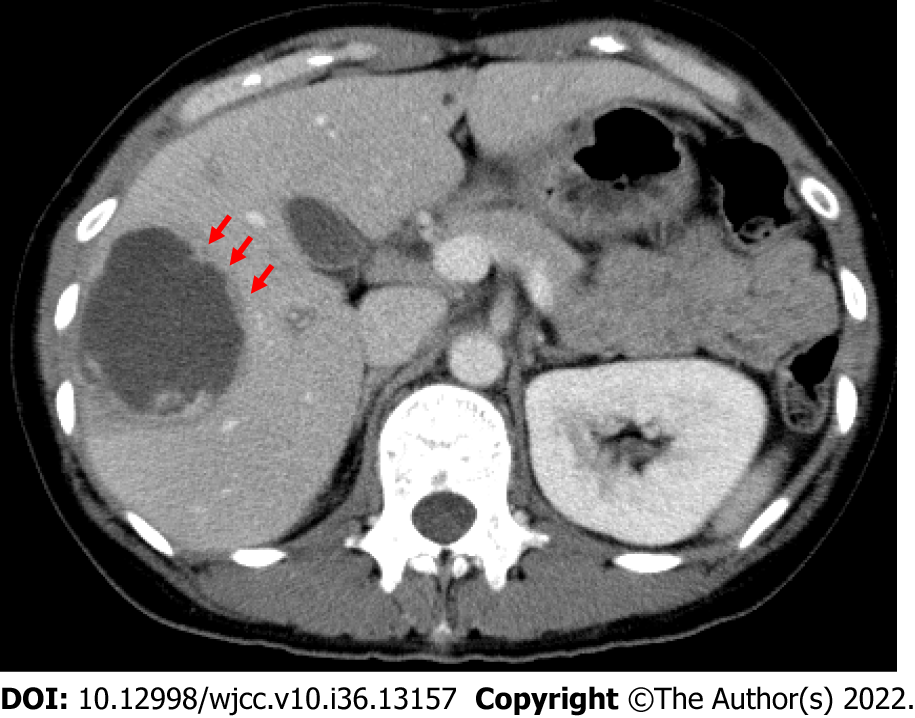

Type I abscesses (representing 66% of the total) have walls that were either absent or incomplete as well as peripheral septa and edges that are ragged and exhibit enhancement that is both irregular and interrupted[38]. Here, we show a CT from our institution of a 44-year-old woman with a type I abscess (Figure 1). Clinically, these abscesses had an acute presentation alongside severe disease. Laboratory parameters were significantly deranged, and they had higher incidences of rupture with higher rates of admission to inpatient care and/or intensive care[38]. In a large majority of type I abscesses (81%), disease severity prompted percutaneous drainage to be carried out immediately[38].

Figure 1 Computed tomography of a 44-year-old woman with a type I abscess.

The axial computed tomography image illustrates the non-enhancing and ragged edge of the abscess in the absence of a definite wall, peripheral septa, and ragged edges; these edges exhibited both irregular and interrupted enhancement (arrows).

Type II abscesses (representing 28% of the total) have complete walls with both peripheral hypodense halo and rim enhancement. Type III abscesses (representing 6% of the total) demonstrate walls but without enhancement[38]. The type II and III abscesses feature delayed presentations, with near-normal laboratory findings and mild to moderate disease[38]. On the other hand, whether ALA patients are infected with HIV cannot be determined through the clinical characteristics alone. Even in the absence of HIV symptoms, it is advisable to routinely test ALA patients for HIV[39].

DIAGNOSIS

Despite the rarity of ALAs, a high index of suspicion should be maintained by physicians working with patients who have presented with synchronous lesions of the colon and liver, particularly because in recent years travel has increased to regions where they are endemic[40]. Crucial predictors of ALAs include habitual alcohol consumption and low socioeconomic status[25]. A number of diagnostic tools are available for diagnosis; if there is a suspicion of amebiasis, testing yield can be maximized through a combination of stool testing and serology[6]. Diagnosis relies on nonspecific liver imaging and on detecting anti-E. histolytica antibodies, which cannot be used to distinguish between acute and previous infections[5,21]. Therefore, diagnostics must focus primarily on detecting E. histolytica using PCR or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay[1]. Among these options, a parallel analysis using indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay with crude soluble antigen together with excretory-secretory antigen for ALA serodiagnosis improved the overall amebic serology efficacy compared to either assay on its own[41].

Recently, the XEh Rapid® IgG4-based rapid dipstick test for rapid detection of ALAs (based on detecting the anti-E. histolytica pyruvate phosphate dikinase IgG4 antibody) demonstrated high diagnostic specificity in infected patients (97%-100%), with diagnostic sensitivity varying between 38% and 94%[42]. The various evaluation process-related difficulties have been discussed elsewhere; nonetheless, it has demonstrated promise for development into a point-of-care test, especially for settings that have relatively restricted resources, and consequently further investigation to confirm its sensitivity as a diagnostic is warranted[42]. On the other hand, one valuable antigen for amebiasis serodiagnosis is the C-terminal region of the intermediate subunit of E. histolytica galactose- and N-acetyl-D-galactosamine-inhibitable lectin[43]. The newly developed immunochromatographic kit, which uses fluorescent silica nanoparticles coated with the C-terminal region of the intermediate subunit of E. histolytica galactose- and N-acetyl-D-galactosamine-inhibitable lectin prepared in Escherichia coli, has proven beneficial for rapid amebiasis serodiagnosis[43].

Ultrasound is currently the criterion standard for liver abscess diagnoses[14]. Acute abdominal pain can be the result of a variety of diseases, but even in non-endemic Western countries parasitic abscess should not be overlooked as a potential diagnosis[14]. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound is a promising new technique, with the potential for greater accuracy in recognizing liver abnormalities, including abscesses; however, definition of differential diagnoses will require retrospective population-wide studies[14].

It is difficult to definitively diagnose ALAs because sensitive point-of-care molecular tests are not readily commercially available[44]. A diagnostic study was performed in order to compare the available methods for E. histolytica laboratory diagnoses in pus samples, stool samples, and blood samples taken from patients who had radiological and/or clinical diagnoses of ALA with loop-mediated isothermal amplification. The results found that loop-mediated isothermal amplification had significantly greater sensitivity (88%) then reverse transcriptase PCR (64%) as well as outstanding specificity (100%)[44]. On the other hand, in ALAs, cell-free circulating E. histolytica DNA can be detected in serum in ALAs, which could prove beneficial for not only positive diagnosis but also the efficacy of follow-up treatments[21]. Additional innovative detecting methods have been developed for E. histolytica, and stool samples were analyzed using PCR-denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis in order to distinguish between pathogenic E. histolytica (pathogenic) and non-pathogenic Entamoeba dispar[45]. The PCR amplification target was a relatively small region (228 bp) of the adh112 gene, which was selected for greater test sensitivity[45]. These results, validated by nested PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism, would imply that PCR-denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis may have promise as a tool to distinguish between Entamoeba infections and contribute to the determination of a specific course of treatment for E. histolytica patients, thus obviating unnecessary treatment of patients who have been infected with Entamoeba dispar, which is non-pathogenic[45].

Additionally, diagnosis is possible through abdominal ultrasound and echography-guided liver puncture[46]. If liver abscess fluid bacterial cultures remain negative, amebic abscess should be considered as a possibility, even if the patient has no personal history of tropical or subtropical travel[1]. In culture-negative cases, 16S rRNA abscess fluid analysis plays a part in improved microbiological diagnoses[35].

TREATMENT

ALAs can be treated medically. Percutaneous catheter drainage (PCD) is required in only 15% of cases[5,47]. They generally respond well to treatment using metronidazole, alongside drainage if indicated[2,4,48]. In uncomplicated cases, it is advisable to avoid surgical drainage[48].

Safe, effective complex abscess decompression has been enabled through surgical drainage with preoperative CT and intraoperative ultrasonography[48]. In particular, liver abscesses in the caudate lobe can be accessed without major complications via different percutaneous drainage routes, despite its deep location and the fact that it is surrounded by large blood vessels[4]. Thus, PCD or percutaneous needle aspiration (PNA) could be regarded as a first-line therapy for caudate lobe amebic abscess management, in adjunct to medical therapy[4]. Following substantial reduction or cessation of PCD output along with clinical recovery, treating physicians may be concerned with residual collections on radiological evaluations[49]. However, both the significance and prevalence of such collections remain unknown, and it is subsequently unclear what approach should be taken in order to tackle them. On the other hand, PCD removal can be expedited successfully in ALAs, even when residual collections are present[49]. In pediatric patients, PNA and drain placement were both found to be effective as ALA treatments, though PNA had greater efficacy[50].

On the other hand, ultrasound-guided PCD has been found to be both safe and effective as a treatment method for ruptured ALAs, including free ruptures with diffuse intraperitoneal fluid collections. For ruptured ALAs, PCD is also recommended as the first line of therapy[51]. At present, metronidazole on its own as well as PNA and PCD play unclear roles in treating uncomplicated ALAs[52]. Compared to metronidazole on its own, PNA results in earlier resolution of both pain and tenderness in patients suffering from medium to large ALAs[52]. On the other hand, PCD is preferable for larger ALAs[52]. However, further efforts to generate more accurate and reliable data are needed due to therapeutic dilemmas caused by discrepancies in randomized controlled trials[52]. In addition, the literature seems to be conflicting on the topic with proponents of both percutaneous methods and laparoscopic drainage[4,53]. Given the rarity of amebiasis, the rarity of the complication itself, and the possibility that PCD may prove ineffective due to viscosity of the abscess content, catheter dislocation etc, a step-up approach would be advisable in that case.

The indicated treatment is to use an amebicidal drug such as metronidazole or tinidazole as well as paromomycin or another luminal cysticidal agent for clinical disease[1,6,54]. Treatment involves oral administration of 500-750 mg of metronidazole (or another nitroimidazole if necessary), three times daily, for 7-10 d[55]. As an alternative option, 2000 mg of tinidazole can be administered orally on a daily basis for 3 d[55]. However, in 40%-60% of patients, the parasites persist within the intestine. Therefore, nitroimidazole treatment should always be followed with a luminal agent such as a 7-d regimen of 500 mg of paromomycin three times a day or a 20-d regimen of 650 mg of iodoquinol three times a day[55].

The drug of choice for treating ALAs is often metronidazole, a common antibacterial and antiprotozoal drug; though it has long been preferred, it is also associated with a number of different adverse effects in some clinical situations, including intolerance[54,56,57]. The mechanisms of resistance to metronidazole, as well as mutagenic potential, have previously been described[23]. Though ordinarily safe, under rare circumstances this drug is capable of causing serious central nervous system disturbances. In particular, metronidazole neurotoxicity as well as characteristic bilateral symmetrical cerebellar dentate hyperintensities have been shown on brain magnetic resonance imaging[58]. However, neurotoxicity is not dependent on dose, and with discontinuation of the drug it can be fully reversed[57,58]. Additionally, it is still unknown what effects, if any, the drug has when used by pregnant or lactating patients (and consequently in breastfeeding infants)[54].

The efficacy of nitazoxanide has been demonstrated in invasive intestinal amebiasis treatment; however, a study has shown that in uncomplicated ALAs nitazoxanide has efficacy comparable to metronidazole and enjoys the advantages of both superior tolerability and simultaneous luminal clearance, leading to a lower likelihood of recurrence[54].

In comparison to metronidazole, tinidazole has an earlier clinical response, a shorter course of treatment, a more favorable rate of recovery, and a higher tolerability; consequently, for ALAs tinidazole can be considered preferable to metronidazole[56]. The recommended treatment for asymptomatic infections is a luminal cysticidal agent, in order to reduce the chances of either invasive disease or transmission[6].

For surgical treatment, a laparoscopic approach imposes the least physical burden resulting from the laparotomy[46]. According to the latest research results, ubiquitin Ehub antibodies are induced solely in patients with ALA or other invasive amoebiasis, and the antibody response is mainly to the glycoprotein, indicating that the glycans are immunodominant[59]. Therefore, Ehub glycan inhibitors hold potential as an amoebiasis treatment through selective damage to trophozoites[59].

COMPLICATIONS

In rare cases, abscesses can rupture into the peritoneum, pericardium, or pleura, or into the hilum of the bile duct; they may also lead to septic emboli[2]. Thromboses of the hepatic vein and the inferior vena cava are uncommon ALA complications (though well documented) and are generally attributed to the inflammation and mechanical compression that accompany larger abscesses[60]. With ALAs, the combination of portal vein thrombosis and hepatic vein thrombosis is a common occurrence, frequently manifesting as segmental hypoperfusion in the portal venous phase and indicating ischemia[61]. When events such as these are detected using CT, they may indicate a more severe disease that demands more aggressive management, including percutaneous drainage[61]. However, there has been one report of a left hepatic ALA in a patient who had no clear source of infection, initially presenting with a left portal vein thrombosis[22].

In rare cases, hepatic artery aneurysms can complicate amebiasis in hepatic abscess patients[13]. In addition to the significant harm caused by the disease, particularly in developing countries, there is only sporadic case report data available, which suggests that there may be an underreporting bias[13]. Further studies are necessary in order to further elucidate vascular involvement in this setting of parasitological interest[13]. Furthermore, intrahepatic pseudoaneurysms due to ALAs are exceptionally uncommon. There are only a handful of published reports[62]. In every known symptomatic case, the treatment was embolization of the hepatic artery; consequently, the natural course of the disease remains poorly understood, as do the effects of abscess drainage on outcomes[62]. On the other hand, according to one report regarding symptomatic intracavitary intrahepatic pseudoaneurysms as a result of an ALA, an ultrasound-guided abscess PCD caused the intrahepatic pseudoaneurysms to spontaneously resolve[62]. Recently, there has been a case reported of ALA copresenting with coronavirus disease 2019. Based on pathophysiological similarities, coinfection with both of these could affect the clinical course of the patient[18].

PROGNOSIS

There are highly varied infection outcomes for amebiasis due to the protozoan parasite E. histolytica[63]. Prognosis is favorable, and there is near-universal recovery[5]. A study of the relationship between the genotypes of parasites and amebic infection outcomes found a significant association with disease outcomes related to single nucleotide polymorphisms (both non-synonymous and synonymous) within the protein 2 (kerp2) locus, which is rich in both lysine and glutamic acid[63]. An incomplete linkage disequilibrium value has also been found to exist at the kerp2 locus, with potential recombination events and significant values for population differentiation[63]. At the kerp2 locus, disease-specific single nucleotide polymorphisms, potential recombination events, and significant values for population differentiation are present, indicating that the host continuously exerts selection pressure on the parasite on the kerp2 gene and its gene products; this could potentially serve as a way to determine the outcome of disease caused by E. histolytica infections[63].

Additionally, in isolation from asymptomatic carriers, E. histolytica is closer, phylogenetically, to species that cause human liver abscesses, and they exhibit potential interpopulation recombination[63]. Individuals who experience persistent asymptomatic infections of E. histolytica could have a greater likelihood of future ALA development, and asymptomatic people who live in areas where it is endemic should always be mandated to undergo close investigations[63]. On the other hand, potentially valuable predictors of recurrent ALA include the presence of resistance genes (nim) and Prevotella in the abscess fluid, accompanied by elevated levels of matrix metalloproteinase-9 and large abscess size (11 cm × 10.8 cm); recurrence rates were 8.9%[64].

PREVENTION

Despite the knowledge that has been gained and the scientific advances that have been made, there are still no effective treatments to prevent this infection[65]. The extended duration of subclinical E. histolytica infection makes it difficult to control this disease not only in individual amebiasis patients but also epidemiologically[24]. Anti-E. histolytica testing targeting individuals who are at greater risk could prove beneficial in early subclinical amebiasis diagnosis, and earlier treatment of infected patients could halt invasive amebiasis from developing, thus preventing community transmission[24].

The compound curcumin can demonstrate anti-amebic effects within the liver, which would suggest that administering curcumin daily could help to significantly decrease infection incidence rates[65]. Immunization using a chimeric vaccine (using the recombinant protein PEΔIII-LC3-KDEL3) was successful in preventing invasive amebiasis, avoiding acute proinflammatory response, and rapidly activating a protective response. Ultimately, this recombinant protein induced increased serum levels of IgG[3]. Additionally, in order to proactively eliminate the disease, it would be beneficial to have greater awareness among at-risk members of the public[8].

CONCLUSION

The aim of this minireview was to highlight the pathogenesis of and difficulty of diagnosing ALAs. Methods of pathogenesis and accurate diagnosis have yet to be determined. However, accurate diagnoses can be achieved through newer molecular biological techniques, and these can lead to appropriate management of infections due to this organism. Future studies should ideally aim to elucidate pathogenesis and determine more effective diagnoses for effective ALA management.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: Japan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Hakimi T, Afghanistan; Pantelis AG, Greece; Priyadarshi RN, India S-Editor: Liu GL L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Liu GL