Published online Dec 6, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i34.12775

Peer-review started: September 27, 2022

First decision: October 13, 2022

Revised: November 3, 2022

Accepted: November 8, 2022

Article in press: November 8, 2022

Published online: December 6, 2022

Processing time: 65 Days and 20 Hours

A perforated gastroduodenal ulcer is rarely observed in children. Certain med

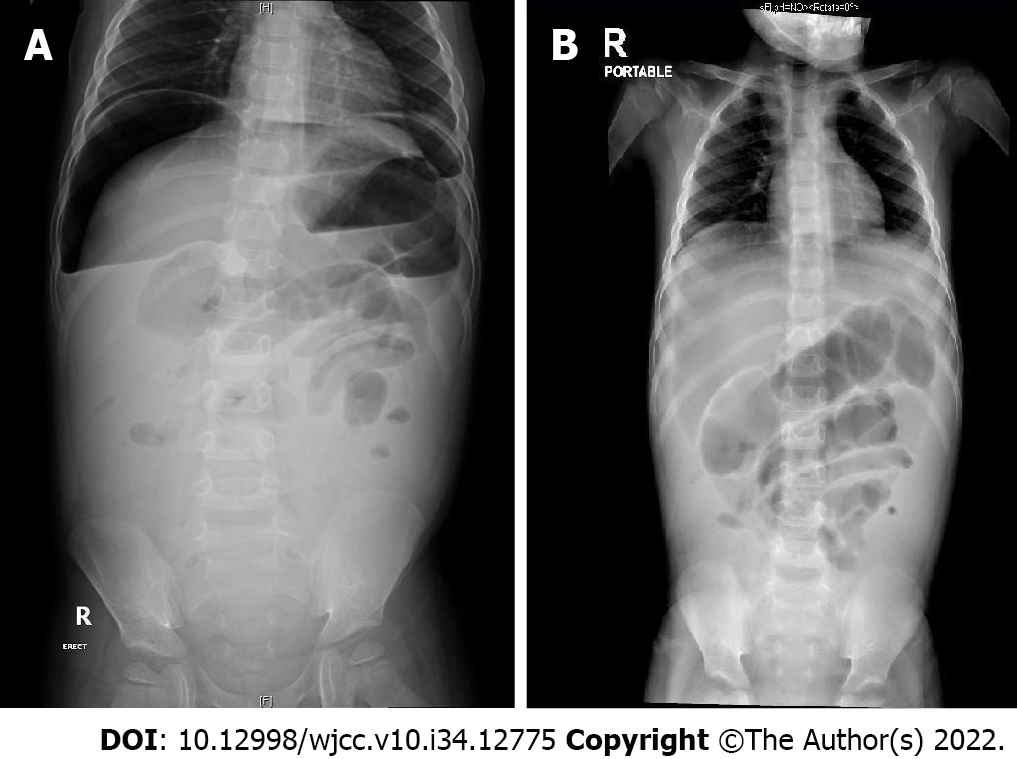

We report a case of a 3-year-old boy who was diagnosed with beta thalassemia major and treated with deferasirox. He presented to the emergency department with an acute abdomen. A perforated duodenal ulcer was suspected after X-ray imaging and laparoscopic exploration. It was successfully managed with laparoscopic washout and drainage.

Due to the rarity and severity of this case, it is a reminder that prevention and early recognition of gastrointestinal complications in patients receiving de

Core Tip: Deferasirox, an iron chelating agent, is associated with gastroduodenal ulcers. However, reports of perforated gastroduodenal ulcers in pediatric patients are rare. The pediatric patient presented in this report was previously diagnosed with beta thalassemia major and was treated with deferasirox. He presented to the emergency department with an acute abdomen. We suspected a perforated duodenal ulcer after X-ray and laparoscopic exploration. The patient recovered well after laparoscopic washout and drainage. Early recognition of this life threatening complication in the pediatric population is essential. Minimally invasive laparoscopic surgery is a safe and feasible management option for perforated duodenal ulcers.

- Citation: Alshehri A, Alsinan TA. Perforated duodenal ulcer secondary to deferasirox use in a child successfully managed with laparoscopic drainage: A case report . World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(34): 12775-12780

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i34/12775.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i34.12775

Peptic ulcer disease (PUD) is relatively uncommon in children, with an estimated incidence of 1.55 cases per year[1,2]. Primary PUD is more common in children over 10-years-old and is often related to Helicobacter pylori infection or acid hypersecretion. Secondary PUD is more common in younger children and usually occurs secondary to sepsis, head trauma, burns, or medications such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and steroids[3]. Although gastroduodenal perforation due to PUD is a rare complication, most cases are primarily secondary to trauma[4].

Cases of duodenal perforation have been reported with various etiologies, including malaria, lymphoma, meningitis, and gastroenteritis[5-9]. The occurrence of gastroduodenal ulceration in patients receiving deferasirox, an iron-chelating drug, has been noted in two publications[10,11]. Surgical repair of duodenal perforation is typically necessary, and laparoscopy is increasingly used[11-15]. To our knowledge, there have been no reported cases in which duodenal perforation in a pediatric patient was managed with laparoscopic drainage, without primary repair. In this paper, we describe a 3-year-old male diagnosed with a perforated duodenal ulcer who was treated successfully with laparoscopic washout and drainage.

A 3-year-old male presented to the emergency department with abdominal pain for 1 d.

The patient was previously diagnosed with beta thalassemia major. He has received multiple blood transfusions and has taken deferasirox, an iron-chelating agent, for longer than a year. Four months before his presentation to the emergency department, the deferasirox dose was increased from 250 mg once daily to 250 mg twice daily. Since then, he had experienced intermittent upper abdominal pain. Three weeks after the dose increase, he presented to the emergency department with generalized abdominal pain and recurrent episodes of vomiting and diarrhea associated with lethargy and fever. The family reported no history of trauma.

Besides diagnosis and treatment of beta thalassemia major, the patient had no other illnesses and no known allergies.

No special personal or family history was reported.

The patient had a fever of 39ºC and tachycardia of 130 beats per minute. His abdominal exam showed moderate distension with generalized tenderness, which was more remarkable on the epigastrium and right upper quadrant.

Blood analysis revealed the following: white blood cell count, 12.8 × 109/L (reference range: 5-15.5 × 109/L); red blood cell count, 2.7 × 1012/L (reference range: 3.9-5.0 × 1012/L); hemoglobin, 73 g/L (reference range: 110-138 g/L); and platelet count, 384 × 109/L (reference range: 150-350 × 109/L). Biochemical analysis revealed normal levels of total protein (58 g/L), albumin (33.4 g/L), creatinine (29 µmol/L), and urea nitrogen (4.4 mol/L).

Perforated duodenal ulcer.

As initial management, the patient was resuscitated with intravenous fluid, broad-spectrum antibiotics, and analgesia. Subsequently, he underwent an urgent diagnostic laparoscopy using a 5-mm umbilical port with two lateral 3-mm ports. Examination of the abdominal cavity revealed a moderate amount of bilious-free fluid and fibrinous reaction in the upper right quadrant, particularly over the upper area of the duodenum. There was no apparent perforation in the visible part of the duodenum. Kocherization of the duodenum was not performed at this stage. The gall bladder, anterior wall of the stomach, small intestine, and colon, including the appendix, were normal in appearance. The lesser sac was opened to examine the posterior wall of the stomach. Due to the inflammation over the duodenum, we suspected a tiny duodenal perforation. The surgeon decided not to explore the area or perform a laparotomy. Instead, the abdomen was irrigated, and two closed suction drains were placed in the hepatic bed and pelvis.

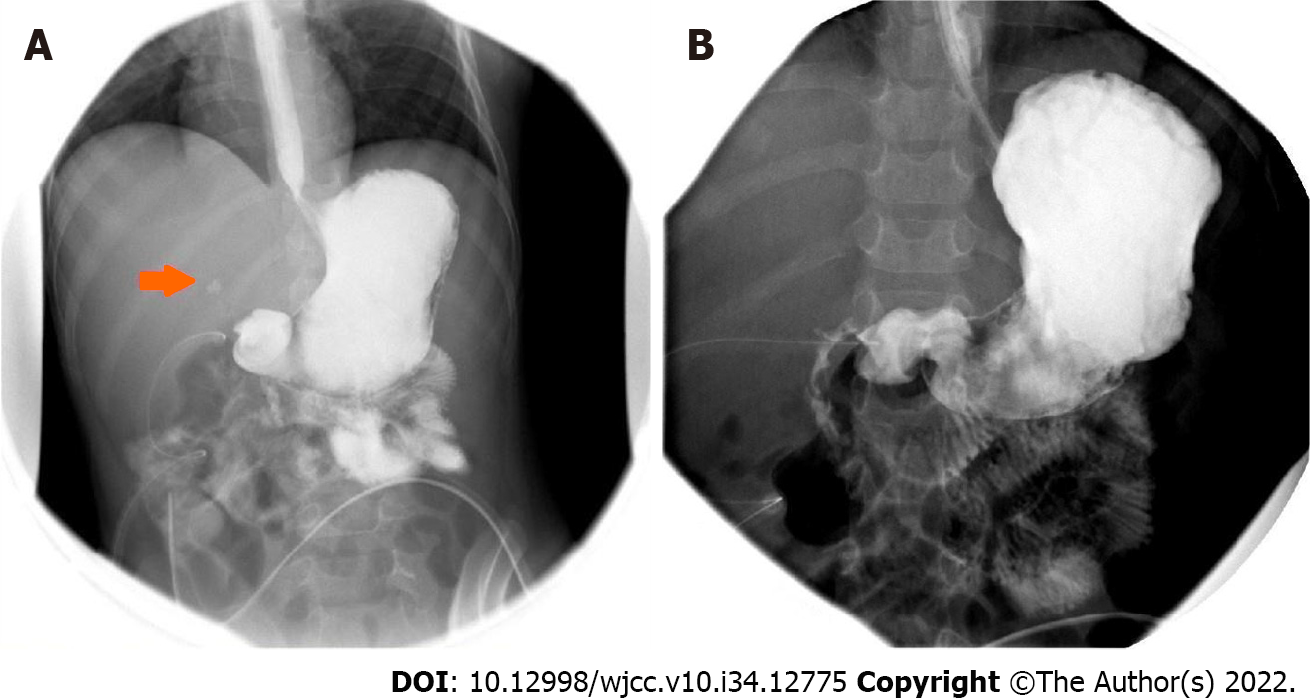

Postoperatively, the patient was admitted to the intensive care unit for 24 h. He was kept nil per os and started on total parenteral nutrition. He received nasogastric decompression, broad-spectrum antibiotics, and acid-suppressing therapy. The patient continued to improve. However, an upper gastrointestinal contrast study performed on postoperative day 5 showed minimal contrast leak from the first part of the duodenum (Figure 2A). Management of the patient continued as previously described. A week later, another upper gastrointestinal contrast study was performed. No contrast leak from the duodenum was observed (Figure 2B). The patient gradually began oral feeding and the abdominal drains were removed before he was discharged.

At the 1-mo follow-up, the patient recovered well and had satisfactory cosmetic results on his abdomen (Figure 3).

Diagnosing perforated pediatric PUD is challenging due to the low incidence rate[1-4]. Most cases of duodenal perforation are due to blunt abdominal trauma[4,11]. Treatment of duodenal perforation is typically surgery. Laparoscopy is being utilized increasingly for diagnosis and repair[4,6-8,11,12]. Although repairing a duodenal perforation is favored, identifying a small perforation is difficult and may require laparotomy to fully mobilize and repair the duodenum. In our case, laparoscopic washout and drainage of the abdomen was a safe and effective method to manage a duodenal perforation that was not easily accessible. While the perforation was healing, our patient remained hospitalized and received acid-suppressing medications and total parenteral nutrition via a peripherally-inserted central catheter. This strategy may not be practical in areas where total parenteral nutrition or vascular access is not readily available. This strategy is the most beneficial for tiny perforations. Traumatic perforations, which tend to be larger, benefit most from primary repair.

Our patient had a previous diagnosis of beta thalassemia major and was treated with an iron chelating medication (oral deferasirox). His gastrointestinal symptoms started after the deferasirox dose was increased, which led to duodenal perforation. In 2005, deferasirox was approved in the United States for use in adults and children over 2-years-old. Apart from its effect on renal function, deferasirox is generally well-tolerated in children. Vomiting and diarrhea are the most common gastrointestinal adverse events. However, ulceration and bleeding have been reported[9,10]. In a case report from Kuwait, a 6-year-old male with beta thalassemia was treated with deferasirox for 3 years. He presented with shock due to a perforated duodenal ulcer and was managed surgically with an omental patch. The ulcer healed but deferasirox was discontinued. This led to high ferritin levels, and iron-chelating therapy was restarted along with administration of a proton pump inhibitor[9]. In another case, a 10-year-old female with beta thalassemia was treated with deferasirox for 5.5 years. She presented with a bleeding gastric ulcer, was negative for Helicobacter pylori infection, and the ulcer healed after deferasirox was discontinued[10].

The pathophysiology of ulcer development with chronic use of deferasirox is not yet understood. Although gastroduodenal ulceration is not widely reported, it remains a significant and potentially life-threatening complication. Prevention and early recognition are essential because long-term iron chelation is often required for patients receiving multiple blood transfusion. An early warning sign may be recurrent abdominal pain, which was observed in our patient and two other reported cases. Acid-suppressing medication and proton pump inhibitors may be appropriate preventive treatments. Further research is warranted to identify the most effective treatments and to determine prevention and recognition strategies.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Pediatrics

Country/Territory of origin: Saudi Arabia

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Qi R, China; Shirini K, Iran S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Kalach N, Bontems P, Koletzko S, Mourad-Baars P, Shcherbakov P, Celinska-Cedro D, Iwanczak B, Gottrand F, Martinez-Gomez MJ, Pehlivanoglu E, Oderda G, Urruzuno P, Casswall T, Lamireau T, Sykora J, Roma-Giannikou E, Veres G, Wewer V, Chong S, Charkaluk ML, Mégraud F, Cadranel S. Frequency and risk factors of gastric and duodenal ulcers or erosions in children: a prospective 1-month European multicenter study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;22:1174-1181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Jamal MH, Karam A, Alsharqawi N, Buhamra A, AlBader I, Al-Abbad J, Dashti M, Abulhasan YB, Almahmeed H, AlSabah S. Laparoscopy in Acute Care Surgery: Repair of Perforated Duodenal Ulcer. Med Princ Pract. 2019;28:442-448. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sullivan PB. Peptic ulcer disease in children. Paediatrics and Child Health. 2010;20:462-464. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Gutierrez IM, Mooney DP. Operative blunt duodenal injury in children: a multi-institutional review. J Pediatr Surg. 2012;47:1833-1836. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Goldman N, Punguyire D, Osei-Kwakye K, Baiden F. Duodenal perforation in a 12-month old child with severe malaria. Pan Afr Med J. 2012;12:1. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Wilson JM, Darby CR. Perforated duodenal ulcer: an unusual complication of gastroenteritis. Arch Dis Child. 1990;65:990-991. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Tanzer F, Baskin E, Içli F, Toksoy H, Gökalp A. Perforated duodenal ulcer: an unusual complication of meningitis. Turk J Pediatr. 1994;36:67-70. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Yadav RP, Agrawal CS, Gupta RK, Rajbansi S, Bajracharya A, Adhikary S. Perforated duodenal ulcer in a young child: an uncommon condition. JNMA J Nepal Med Assoc. 2009;48:165-167. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Ueda N. Gastroduodenal Perforation and Ulcer Associated With Rotavirus and Norovirus Infections in Japanese Children: A Case Report and Comprehensive Literature Review. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2016;3:ofw026. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Huang CL, Lee JY, Chang YT. Early laparoscopic repair for blunt duodenal perforation in an adolescent. J Pediatr Surg. 2012;47:E11-E14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Clendenon JN, Meyers RL, Nance ML, Scaife ER. Management of duodenal injuries in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2004;39:964-968. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Urs AN, Narula P, Thomson M. Peptic ulcer disease. Paediatrics and Child Health. 2014;24:485-490. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 13. | Tarasconi A, Coccolini F, Biffl WL, Tomasoni M, Ansaloni L, Picetti E, Molfino S, Shelat V, Cimbanassi S, Weber DG, Abu-Zidan FM, Campanile FC, Di Saverio S, Baiocchi GL, Casella C, Kelly MD, Kirkpatrick AW, Leppaniemi A, Moore EE, Peitzman A, Fraga GP, Ceresoli M, Maier RV, Wani I, Pattonieri V, Perrone G, Velmahos G, Sugrue M, Sartelli M, Kluger Y, Catena F. Perforated and bleeding peptic ulcer: WSES guidelines. World J Emerg Surg. 2020;15:3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 202] [Cited by in RCA: 163] [Article Influence: 32.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Tytgat SH, Zwaveling S, Kramer WL, van der Zee DC. Laparoscopic treatment of gastric and duodenal perforation in children after blunt abdominal trauma. Injury. 2012;43:1442-1444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Raphael JL, Bernhardt MB, Mahoney DH, Mueller BU. Oral iron chelation and the treatment of iron overload in a pediatric hematology center. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2009;52:616-620. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |