Published online Dec 6, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i34.12648

Peer-review started: July 4, 2022

First decision: August 1, 2022

Revised: August 5, 2022

Accepted: November 7, 2022

Article in press: November 7, 2022

Published online: December 6, 2022

Processing time: 151 Days and 3.4 Hours

Aggressive vertebral hemangioma (VH) is an uncommon lesion in the adult population. The vast majority of aggressive VHs have typical radiographic features. However, preoperative diagnosis of atypical aggressive VH may be difficult. Aggressive VHs are likely to recur even with en bloc resection.

A 52-year-old woman presented with a 3-mo history of numbness and pain in her right lower extremity. Physical examination showed sacral tenderness and limited mobility, and the muscle strength was grade 4 in the right digital flexor. Computed tomography revealed osteolytic bone destruction from S1 to S2. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed that the mass was compressing the dural sac; it was heterogeneously hypointense on T1-weighted MRI and hype

The radiographic findings of atypical aggressive VH include osteolytic vertebral bone destruction, extension of the mass into the spinal canal, and heterogeneous signal intensity on T1-, T2-, and enhanced T1-weighted MRI. These characteristics make preoperative diagnosis difficult, and biopsy is necessary to verify the lesion. Surgical decompression and gross total resection are recommended for treatment of aggressive VH. However, recurrence is inevitable in some cases.

Core Tip: Aggressive vertebral hemangioma is characterized by osteolytic vertebral bone destruction and may extend into the spinal canal. Atypical aggressive vertebral hemangioma exhibits heterogeneous signal intensity on T1-, T2-, and enhanced T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging. Recurrence is inevitable in some cases.

- Citation: Wang GX, Chen YQ, Wang Y, Gao CP. Atypical aggressive vertebral hemangioma of the sacrum with postoperative recurrence: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(34): 12648-12653

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i34/12648.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i34.12648

Vertebral hemangioma (VH) is among the most common benign spinal vascular malformations. The diagnosis of VH depends on its imaging appearance, including computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Typical VH is characterized by coarse vertical trabeculae on radiographic and CT images and hyperintensity on T1- and T2-weighted MRI. Atypical VH exhibits osteolytic vertebral bone destruction, vertebral compression fractures, and atypical enhanced or unenhanced MRI signals[1]. Aggressive VH may extend into the spinal canal and/or paravertebral space, resulting in spinal cord compression and neurological deficits. Aggressive VH accounts for approximately 1% of all cases of VH[2]. We herein report a case of aggressive VH of the sacrum with an atypical radiographic appearance and recurrence 6 mo after surgery.

A 52-year-old woman presented with a 3-mo history of intermittent attacks of numbness and pain in her right lower extremity.

The patient was referred to our institution because her symptoms were not relieved after conservative treatment.

The patient denied a history of hepatitis, tuberculosis, hypertension, diabetes, and drug allergy.

The patient had no other significant medical history.

Physical examination revealed tenderness, percussion pain, and limited mobility in the area of the right sacrum. No hypoesthesia of the skin was present. Muscle strength was grade 4 in right plantar flexion. No amyotrophy, paralysis, or ataxia was observed. The Babinski sign, Gordon sign, and Hoffmann sign were negative.

Laboratory tests including blood cell count, renal and liver function tests, and erythrocyte sedimen

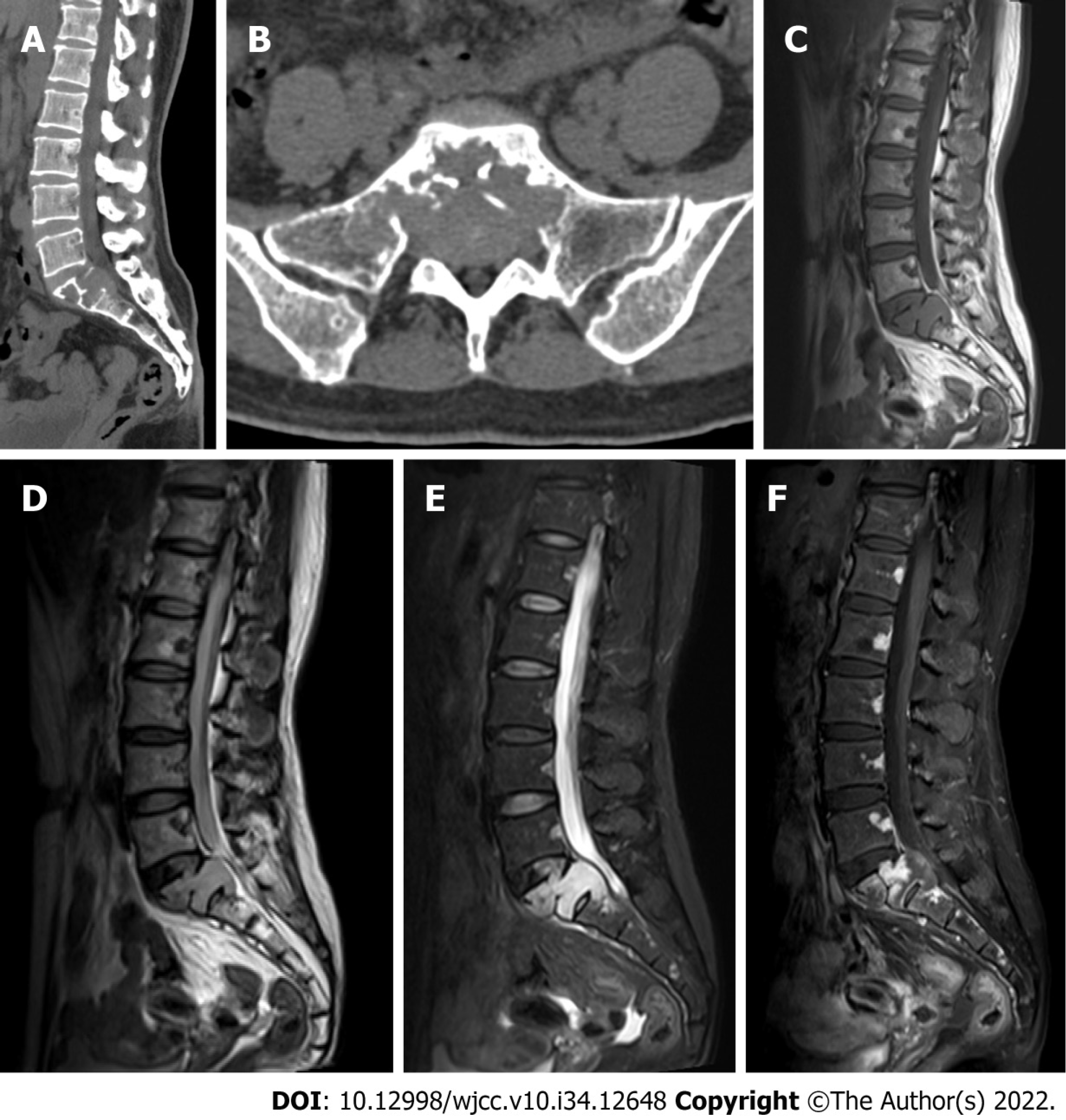

CT showed osteolytic vertebral bone destruction at S1 with a residual coarse crest and soft mass protruding into the spinal canal (Figure 1A and B). MRI showed a soft tissue mass occupying the vertebral body of S1 with involvement of the posterosuperior aspect of the S2 vertebral body. The mass was isointense on T1-weighted MRI and heterogeneously hyperintense on T2-weighted MRI (Figure 1C and D). The thecal sac was compressed by the mass at S1 (Figure 1D and E). Significant heterogeneous signal intensity was shown by MRI after gadolinium contrast enhancement (Figure 1F). The vertebral endplate was interrupted by the mass (Figure 1D).

Our preliminary diagnosis was solitary bone plasmacytoma.

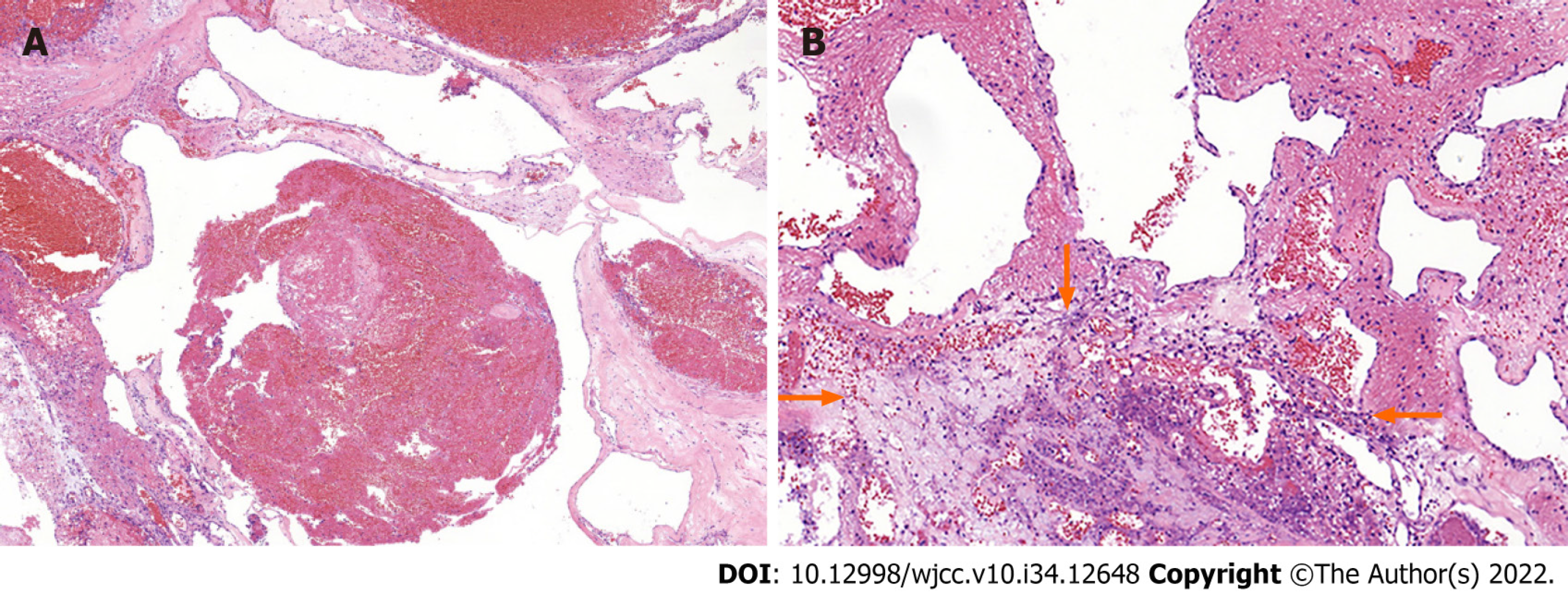

On the basis of the clinical and imaging findings, we performed an operation to remove the tumor along with segmental pedicle fixation. After successful induction of general anesthesia, a straight midline incision of about 16 cm in length was made over the center of the tumor. After removal of the L5–S1 Laminas and ligament flavum, the tumor was exposed. The tumor was located ventral to the thecal sac at S1 and measured 5 cm × 4 cm × 6 cm in size. It was reddish in color, tough in consistency, and well demarcated. The tumor was completely removed, and no residual tumor tissue was seen. The surrounding nerves and vessels were carefully protected, bilateral crest screws were inserted and connected to the pedicle screw in L5, and the nuts were fastened. A drain was left in the incision. After hemostasis was confirmed, the muscle layer, subcutaneous tissue, and skin were sutured closed. The tumor specimen was sent for histopathological examination. Microscopically, the tumor was composed of thin-walled vessels lined with a single layer of flat endothelial cells. The diameter and wall thickness of the proliferated vessels were not uniform. Regions of blood stasis containing red blood cells and cellulose were observed, and an area of inflammatory necrosis was present (Figure 2).

The patient’s numbness and pain in the right lower extremity improved immediately after the operation. Six months postoperatively, however, the patient developed rapidly progressive lumbosacral pain. Repeat MRI showed recurrence of the mass at S1/2; it was larger than in the previous examination, and it was compressing the thecal sac (Figure 3). The patient refused reoperation and instead received conservative medical treatment.

VH is an extremely common benign lesion characterized by proliferation of blood vessels. It is considered to be a lesion of dysembryogenetic origin or a hamartomatous lesion. Perman[3] was the first to describe the radiographic features of typical VH in 1926. The incidence of VH is about 11% in the adult population[4], and the prevalence of VH seems to increase with age. The vast majority of VHs are asymptomatic and quiescent lesions. They are usually an incidental finding on spinal MRI or CT. VH is most frequently found in the thoracic spine, followed by the lumbar and cervical spine; sacral involvement is rare[1]. Multiple-level involvement reportedly occurs in as many as 30% of cases. VH is usually confined to the vertebral body, although it may occasionally extend into the posterior elements. Plain radiographs of VH may reveal either parallel linear streaks or a “honeycombed” appearance. CT scans can also demonstrate the classic “honeycomb” sign or vertically oriented vertebral lucencies separated by thickened trabecular bone. Typical VH appears as a well-defined and hyperintense lesion on T1- and T2-weighted MRI with fat predominance. VH can grow quickly, extending beyond the vertebral cortex and into the paravertebral and/or epidural space with compression of the spinal cord and/or nerve roots; such tumors are termed aggressive VH[2]. Cauda equina syndrome and radiculopathy usually present as lower extremity numbness associated with progressive motor weakness. Sphincteric disturbances are late manifestations[5,6]. Atypical VH has less fatty tissue and greater vascular content[7]. Wang et al[1] summarized the imaging features of atypical VH as follows: Expansive and osteolytic vertebral bone destruction, vertebral body compression fractures, involvement of more than one segment or longitudinally of soft tissue extending beyond one segment, epidural soft tissue compression of the spinal cord, the lesion centered in the neural arch, and atypical enhanced or unenhanced MRI signals. Atypical aggressive VH is uncommon; Wang et al[1] reported 34 patients with atypical aggressive VH in their institution, and 1 Lesion was located in the sacrum. The authors reviewed the literature of the past 20 years and identified 45 cases of atypical aggressive VH[1]. The aggressive VH in our case originated from the sacrum and exhibited atypical features.

Our patient’s lesion showed osteolytic bone destruction without a honeycomb appearance and without a “polka-dot” sign. The superior vertebral endplate of S1 was interrupted as clearly shown on sagittal MRI. The lesion showed isointense signals on T1-weighted MRI and hyperintense signals on T2-weighted MRI, and it exhibited heterogeneous enhancement on post-contrast images. The lesion occupied the whole S1 and involved the posterior aspect of S2. Epidural osseous compression resulted in radiculopathy. According to the diagnostic standards described by Wang et al[1], our patient exhibited five atypical radiographic features of aggressive VH. Decompression with laminectomy should be performed in patients with rapid and progressive neurological deficits. The cure rate for VH without extraosseous soft tissue extension using laminectomy ranges from 70% to 80%[8,9]. Acosta et al[10] reported six patients who underwent decompressive laminectomy in their series, and two patients required reoperation for recurrence. For aggressive VH causing cord compression and neurological deficits, more radical surgical resection has been advocated. The postoperative recurrence rates of aggressive VH remain controversial based on the results of different studies. Goldstein et al[11] reported 2 cases of recurrence among 68 patients with VH, and the recurrences developed at 4.4 and 5.3 years after the operation, respectively. Wang et al[12] reported 20 aggressive VHs that were surgically treated, and 3 of the 20 patients had undergone surgical decompression at other institutions. Therefore, postoperative recurrence of aggressive VH depends not only on the intraosseous and epidural extension of the lesion but also on the experience of the operator. Our patient developed recurrence 6 mo after the operation, and she experienced progressive lower back pain. MRI showed that the soft tissue mass had increased in size and was compressing the thecal sac more severely than before.

Differential diagnoses of VH include metastasis, solitary bone plasmacytoma, and epithelioid hemangioendothelioma. Osteolytic vertebral metastases may present with cortical expansion and as soft tissue masses. The definitive diagnosis can be difficult and often requires all radiological imaging modalities in addition to histopathological examination[13]. The classic radiological appearance of solitary bone plasmacytoma is described as a “mini brain” appearance on axial CT and MRI. However, one-third of cases may mimic aggressive VH, and the differential diagnosis is very challenging[13]. Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma is a rare mesenchymal neoplasm. The tumor shows a lytic pattern of bone destruction on CT, mixed signal intensity on T1- and T2-weighted MRI, and nonspecific radiological features.

VH of the spine shows hyperintensity or hypointensity on T1-weighted MRI and hyperintensity on T2-weighted MRI. Aggressive VH extending beyond the vertebral body and invading the epidural space causes compressive myelopathy. Atypical aggressive VH of the spine with heterogeneous signal intensity on T1- and T2-weighted MRI and enhanced T1-weighted MRI without a characteristic imaging appearance may be diagnosed as malignant before the operation. Biopsy is necessary to achieve a correct diagnosis. We have herein described an atypical aggressive VH of the spine with recurrence 6 mo postoperatively. Therefore, continued clinical presentation and MRI follow-up are necessary for aggressive VH.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Clinical neurology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Muthu S, India; Singh SP, United States S-Editor: Xing YX L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Wang B, Zhang LH, Yang SM, Han SB, Jiang L, Wei F, Yuan HS, Liu XG, Liu ZJ. Atypical Radiographic Features of Aggressive Vertebral Hemangiomas. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2019;101:979-986. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Hurley MC, Gross BA, Surdell D, Shaibani A, Muro K, Mitchell CM, Doppenberg EM, Bendok BR. Preoperative Onyx embolization of aggressive vertebral hemangiomas. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2008;29:1095-1097. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Perman E. On haemangiomata in the spinal column. Acta Chit Scand. 1926;61:91-105. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Huvos AG. Hemangioma, lymphangioma, angiomatosis/lymphangiomatosis, glomus tumor. In: Huvos AG, editor. Bone tumors: diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders 1991; 553–578. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 5. | Nassar SI, Hanbali FS, Haddad MC, Fahl MH. Thoracic vertebral hemangioma with extradural extension and spinal cord compression. Case report. Clin Imaging. 1998;22:65-68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ergun T, Lakadamyali H, Mukaddem A. Acute spinal cord compression from an extraosseous vertebral hemangioma with hemorrhagic components: a case report. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2007;30:602-606. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Dang L, Liu C, Yang SM, Jiang L, Liu ZJ, Liu XG, Yuan HS, Wei F, Yu M. Aggressive vertebral hemangioma of the thoracic spine without typical radiological appearance. Eur Spine J. 2012;21:1994-1999. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Mohan V, Gupta SK, Tuli SM, Sanyal B. Symptomatic vertebral haemangiomas. Clin Radiol. 1980;31:575-579. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Fox MW, Onofrio BM. The natural history and management of symptomatic and asymptomatic vertebral hemangiomas. J Neurosurg. 1993;78:36-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 251] [Cited by in RCA: 221] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Acosta FL Jr, Sanai N, Chi JH, Dowd CF, Chin C, Tihan T, Chou D, Weinstein PR, Ames CP. Comprehensive management of symptomatic and aggressive vertebral hemangiomas. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2008;19:17-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Goldstein CL, Varga PP, Gokaslan ZL, Boriani S, Luzzati A, Rhines L, Fisher C G, Chou D, Williams RP, Dekutoski MB, Quraishi NA, Bettegowda C, Kawahara N, Fehlings MG. Spinal hemangiomas: results of surgical management for local recurrence and mortality in a multicenter study. Spine. 2015;140:656-664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Wang B, Meng N, Zhuang HQ, Han SB, Yang SM, Jiang L, Wei F, Liu XG, Liu ZJ. The Role of Radiotherapy and Surgery in the Management of Aggressive Vertebral Hemangioma: A Retrospective Study of 20 Patients. Med Sci Monit. 2018;24:6840-6850. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Rodallec MH, Feydy A, Larousserie F, Anract P, Campagna R, Babinet A, Zins M, Drapé JL. Diagnostic imaging of solitary tumors of the spine: what to do and say. Radiographics. 2008;28:1019-1041. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 216] [Cited by in RCA: 186] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |