Published online Dec 6, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i34.12631

Peer-review started: September 3, 2022

First decision: September 26, 2022

Revised: September 30, 2022

Accepted: November 7, 2022

Article in press: November 7, 2022

Published online: December 6, 2022

Processing time: 90 Days and 11.1 Hours

A “cannot intubate, cannot oxygenate (CICO)” situation is a life-threatening condition that requires emergent management to establish a route for oxygenation to prevent oxygen desaturation. In this paper, we describe airway management in a patient with an extended parotid tumor that invaded the airways during CICO using the endotracheal tube tip in the pharynx (TTIP) technique.

A 43-year-old man was diagnosed with parotid tumor for > 10 years. Computed tomography and nasopharyngeal fiberoptic examination revealed a substantial mass from the right parotid region with a deep extension through the lateral pharyngeal region to the retropharyngeal region and obliteration of the naso

Using an endotracheal tube as a supraglottic airway device, patients may have increased survival without experiencing life-threatening desaturation.

Core Tip: In the induction of a patient with an extended parotid tumor that invaded the airways, sudden loss of a definite airway occurred. We applied the endotracheal tube tip in the pharynx technique by leaving the tip of the endotracheal tube in front of the glottis outlet with our hand enclosing the patient’s nose and mouth to initiate ventilation. This technique not only buys us time to perform front-of-neck access of the airway or prepare other tools for reintubation but also avoids life-threatening desaturation in a “cannot intubate, cannot oxygenate” situation.

- Citation: Lin TC, Lai YW, Wu SH. Emergent use of tube tip in pharynx technique in “cannot intubate cannot oxygenate” situation: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(34): 12631-12636

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i34/12631.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i34.12631

Difficult airway poses challenges to all anesthesiologists. Till now, there is no specific consensus for the management of an anticipated difficult airway[1]. In critical situations where we failed to secure the airway with videolaryngoscopy intubation, supraglottic airway device, or mask ventilation, front-of-neck access might be the last measure to rescue the patient[2]. What else can be done in this kind of situation?

In this study, we applied the endotracheal tube tip in the pharynx (TTIP) technique to manage such a situation[3,4]. By leaving the tip of the endotracheal tube in front of the patient’s glottis outlet, attaching it to the anesthetic machine, and with our hand enclosing the patient’s nose and mouth, we were then able to initiate ventilation. This technique not only buys us time to perform front-of-neck access of the airway or prepare other tools for reintubation but also avoids life-threatening desaturation in a “cannot intubate, cannot oxygenate (CICO)” situation.

We report the case of a 43-year-old otherwise healthy man (weight, 65 kg; height, 174 cm; body mass index, 21.4 kg/m²) who was scheduled for elective tracheostomy and parotid tumor excision. His chief complaint was dysphagia for months.

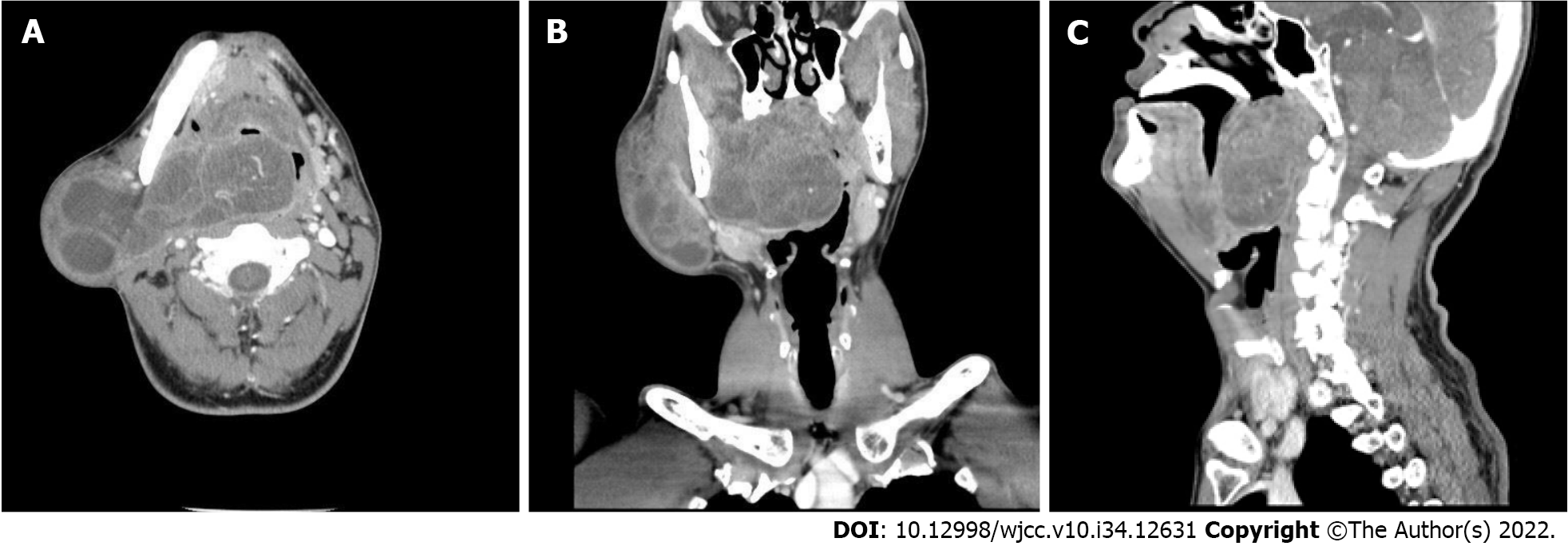

The tumor was recognized since 10 years ago, but the patient refused surgical treatment at the time. It became larger and progressively extended to the nasopharynx and oropharynx, leading to a muffled voice, dysphagia, and mild dyspnea in the supine position (Figure 1).

There was no relevant history of past illness.

There was no relevant family history of cancer or chronic disease. The patient was otherwise healthy other than having a parotid tumor, alcohol drinking, and betelnut chewing history for > 10 years.

Preoperative assessment concluded him as a patient with difficult airway (Mallampati class IV). His thyromental distance was 6 cm; inter-incisor gap, 4 cm; and head extension, > 35°. There were no abnormal breathing sounds on physical examination. He was classified as having American Society of Anesthesiology class III status.

Blood cell count, electrolytes, and biochemistry parameters were all within normal limit.

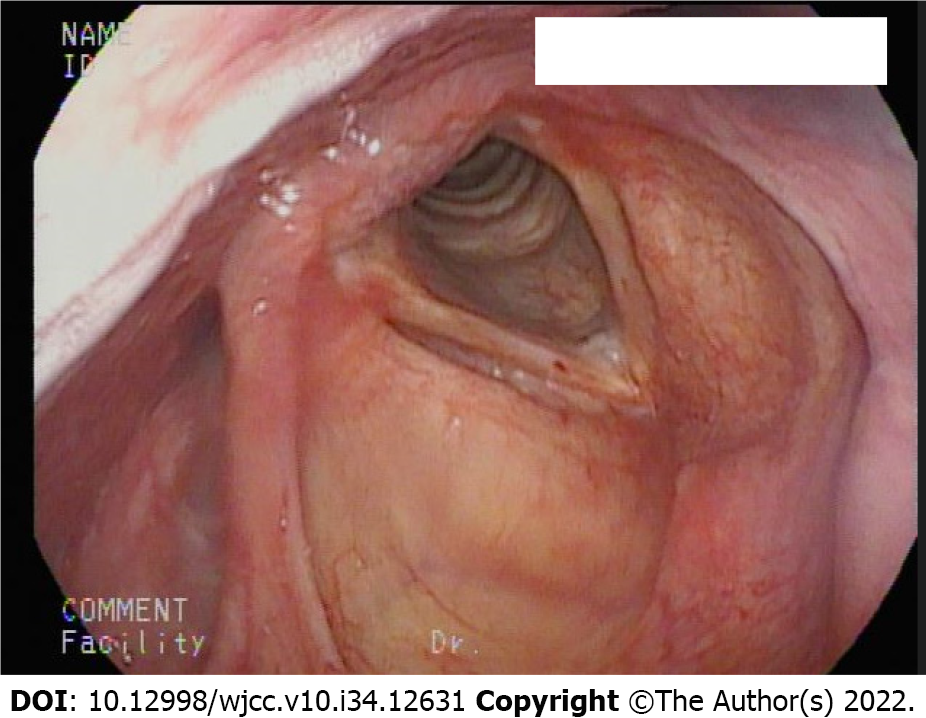

Computed tomography and nasopharyngeal fiberoptic examination revealed a huge mass from the right parotid region and deeply extended through the lateral pharyngeal region to the retropharyngeal region and obliteration of the nasopharynx to the oropharynx (Figure 2). However, fiberoptic examination from the oral approach also demonstrated a clear view of the laryngeal inlet after bypassing the tumor (Figure 3).

Benign parotid tumor was suspected preoperatively. Benign pleomorphic adenoma of the parotid gland was finally confirmed by pathology.

The patient’s otolaryngologist arranged tumor excision surgery under general anesthesia. Although an awake tracheostomy was introduced to the patient initially, out of fear, he asked for tracheostomy under general anesthesia. There was no sign of respiratory distress at the time, and his previous oral fiberoptic examination demonstrated that oral intubation was possible. Thus, our medical team and the patient came to an agreement that we would try awake intubation first if he can cooperate well, and we would anesthetize him after securing definite airway and then perform tracheostomy. If there were signs of dyspnea occurred during intubation, we would shift to awake tracheostomy immediately.

On the operation day, he was admitted to the operating theater and subsequently received fentanyl 50 μg. Then, 2 mL of 10% lidocaine was sprayed to his tongue base as topical anesthesia for awake intubation. There was no stridor nor respiratory distress under semi-Fowler’s position. No additional sedative drug was given for fear that his muscle tone and patency of upper airway will be affected. Then, 6 L/min pure oxygen mask was given for preoxygenation for 5 min and paraoxygenation during intubation. As his nasopharynx is nearly completely obstructed, awake fiberoptic guided naso-endotracheal intubation was impossible and high-flow nasal cannula was not used for the same reason. Trachway and fiberoptic oral intubation appeared to be the remaining choices at the time.

We adopted Trachway with the retromolar technique to pass through the narrowest part between the oropharynx and tumor, and the laryngeal inlet can be visualized. The first intubation attempt with a 6.5-mm tube failed because the angle of the device to the glottis was too sharp; thus, the endotracheal tube could not pass beyond the vocal cord. Consequently, we changed the 6.5-mm endotracheal tube to a 5.5-mm tube for the next attempt. The patient was not dyspneic during our first attempt other than coughing three times because the 6.5-mm tube impinged his vocal cord. Subsequently, his respiratory pattern returned to normal after a short break. His SpO2 was 100% with 6 L/min oxygen mask delivered during the procedure. The second attempt with the 5.5-mm endotracheal intubation appeared successful. We watched the tube passing through the vocal cord, and the anesthesia machine demonstrated five consecutive waves of end-tidal CO2 that reached 40 mmHg following spontaneous breathing with 400 mL of tidal volume. The tube was fixed 23 cm in depth with the cuff inflated. We thought that the airway was already secured; thus, 120 mg propofol was then administered for hypnosis. However, the end-tidal CO2 waveform disappeared right after propofol injection even with positive pressure oxygen delivered. A CICO situation has occurred. Owing to the suspicion of endotracheal tube dislodgement or kinking, the ear, nose, and throat (ENT) doctor then commenced performing tracheostomy to secure a definite airway. Meanwhile, we emergently used the TTIP technique to ventilate the patient. With our hands closing the patient’s mouth and nose creating an enclosed space, the tube was withdrawn to the glottis outlet, and effective bag-valve positive pressure (inspiratory pressure of 20 mmHg) ventilation with 300 mL of tidal volume was achieved. We then continued this technique to ventilate the patient until tracheostomy was completed 9 min later. Subsequent arterial blood gas analysis revealed pH 7.411, PaCO2 of 35.7 mmHg, and PaO2 of 242.5 mmHg upon 50% oxygenation, demonstrating that adequate ventilation is possible by applying this technique. Throughout the course, the SpO2 remained 100%, and no tumor bleeding or gastric distention had been noticed. The patient was transited to T-Piece 6 L/min uneventfully after 9-h surgery.

Feeding via a nasogastric tube for wound protection was applied during admission. The patient was discharged 2 wk later. Further swallowing rehabilitation was arranged. Final pathology revealed benign pleomorphic adenoma of the parotid gland. There was no metastasis of lymph nodes being noticed.

A CICO situation is every anesthesiologist’s nightmare. Current guidelines have focused on maintaining oxygenation via intubation, supraglottic airway devices, mask ventilation, front-of-neck access, or even waking up the patient in such a situation[2,5]. However, in patients with distorted and known difficult airway anatomy, fewer options are available. By applying the TTIP technique, we might be able to prevent situations from worsening. The point is to use our hands in closing the patient’s mouth and nose to create an enclosed space, and only the endotracheal tube tip is left in front of the patient’s glottis outlet. Theoretically, positive oxygen delivery at the moment would either go into the lungs or esophagus if the space is perfectly sealed. Most healthy adults have upper esophageal sphincter resting pressure of > 30 mmHg[6]; thus, a gentle positive pressure ventilation of 15-20 mmHg is less likely to cause gastric distention or aspiration if the tube appropriately positioned. If it was placed too deep, the tube may go into the upper esophagus. All the air for ventilation would erroneously enter the gastrointestinal tract and increase the risk of aspiration.

In our case, we suddenly lost control of the airway in the patient who was extremely difficult to intubate. Although end-tidal CO2 is a great indicator for successful intubation, fiberoptic confirmation of the tracheal ring or carina should have been conducted in this situation because the traditional laryngeal mask airway, oral airway, and nasal airway would not allow entry into the patient’s oropharynx because of tumor obstruction. What else could we do other than the front-of-neck access (which ENT doctors were already doing) to resume effective oxygenation? We attempted the TTIP technique, which resolved this airway crisis. The technique may be a life-saving straw to ventilate patients in a CICO situation when other tools are unavailable or impractical.

In other clinical scenarios, we can apply this technique temporarily, such as accidental endotracheal tube dislodgement when withdrawing the tube in percutaneous dilatational tracheostomy operation or naso-endotracheal intubation for dental, orthognathic, and plastic surgeries, often performed via direct laryngoscopy[7]. The odds that each time an anesthesiologist encountered an unanticipated difficult airway and difficult direct laryngoscopy can be up to 0.9% and 1.5%-8.5%, respectively[8]. The first intubation attempt in naso-endotracheal intubation may fail, and the preparation for the next attempt may be needed some time. Removing a naso-endotracheal tube and resuming to traditional mask ventilation are rational and effective at the most of the times. However, once the tube is removed, the damaged mucosa is no longer compressed, and the previous injury from the nostril could bleed again, worsening the view of next intubation attempt. Even worse, the mixture of blood and secretion may cause disastrous aspiration. By applying the technique, the risk of bleeding and thus aspiration could be minimized.

A CICO situation can be lethal. Clinicians should make every effort to prevent desaturation in airway management. The TTIP technique is easy to perform and can effectively maintain oxygenation. This technique is another option to deal with airway crises. This technique can also be temporarily used in other clinical scenarios but should not be attempted initially when a more definite airway can be established.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Corresponding Author’s Membership in Professional Societies: Taiwan Society of Anesthesiologists, V1646.

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: Taiwan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Chen ZH, China; Gupta N, India S-Editor: Wang JJ L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Wang JJ

| 1. | Cook TM, Morgan PJ, Hersch PE. Equal and opposite expert opinion. Airway obstruction caused by a retrosternal thyroid mass: management and prospective international expert opinion. Anaesthesia. 2011;66:828-836. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Frerk C, Mitchell VS, McNarry AF, Mendonca C, Bhagrath R, Patel A, O'Sullivan EP, Woodall NM, Ahmad I; Difficult Airway Society intubation guidelines working group. Difficult Airway Society 2015 guidelines for management of unanticipated difficult intubation in adults. Br J Anaesth. 2015;115:827-848. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1399] [Cited by in RCA: 1321] [Article Influence: 132.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kristensen MS. Tube tip in pharynx (TTIP) ventilation: simple establishment of ventilation in case of failed mask ventilation. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2005;49:252-256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Mørkenborg ML, Kristensen MS. Tube tip in pharynx-a conduit for awake oral intubation in patients with extremely restricted mouth opening. Can J Anaesth. 2022;69:504-508. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Charco-Mora P, Urtubia R, Reviriego-Agudo L. The Vortex model: A different approach to the difficult airway. Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim (Engl Ed). 2018;65:385-393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Rezende DT, Herbella FA, Silva LC, Panocchia-Neto S, Patti MG. Upper esophageal sphincter resting pressure varies during esophageal manometry. Arq Bras Cir Dig. 2014;27:182-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Chauhan V, Acharya G. Nasal intubation: A comprehensive review. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2016;20:662-667. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Crosby ET, Cooper RM, Douglas MJ, Doyle DJ, Hung OR, Labrecque P, Muir H, Murphy MF, Preston RP, Rose DK, Roy L. The unanticipated difficult airway with recommendations for management. Can J Anaesth. 1998;45:757-776. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 418] [Cited by in RCA: 369] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |