Published online Dec 6, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i34.12566

Peer-review started: July 13, 2022

First decision: August 6, 2022

Revised: September 28, 2022

Accepted: November 8, 2022

Article in press: November 8, 2022

Published online: December 6, 2022

Processing time: 141 Days and 20.7 Hours

Direct acting antivirals (DAAs) are a very effective treatment for hepatitis C virus (HCV). However, brand DAAs are expensive. The licensing of cheaper generic DAAs may address this issue, but there is a lack of clinical studies comparing the efficacy of generic vs brand DAA formulations.

To compare the efficacy and safety of generic against brand DAAs for chronic hepatitis C treatment in Bahrain.

This was a retrospective observational study involving 289 patients with chronic HCV infection during 2016 to 2018. There were 149 patients who were treated with brand DAAs, while 140 patients were treated with generic DAAs. Commonly used DAAs were Ombitasvir/Paritaprevir/Ritonavir ± Dasabuvir ± Ribavirin, and Sofosbuvir/Daclatasvir ± Ribavirin. SVR at 12 wk post treatment was the main outcome variable.

Overall, 87 patients (30.1%) had cirrhosis and 68.2% had genotype 1 HCV infection. At 12 wk post treatment, SVR was achieved by 271 (93.8%) of the patients. In patients who were treated with generic medications, 134 (95.7%) achieved SVR at 12 wk post treatment, compared to 137 (91.9%) among those treated with brand medications (P = 0.19). Having cirrhosis [odds ratio (OR): 9.41, 95% confidence interval (CI): 2.47–35.84] and having HCV genotype 3 (OR: 3.56, 95%CI: 1.03–12.38) were significant independent predictors of not achieving SVR. Alanine transaminase, gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase, and total bilirubin levels decreased significantly following therapy with both generic and brand DAAs.

Generic and brand DAAs demonstrate comparable effectiveness in the treatment of chronic hepatitis C patients. Both are safe and equally effective in improving biochemical markers of hepatic inflammation.

Core Tip: The World Health Organization aims to eliminate hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection by 2030. Its guidelines recommend treatment for all individuals diagnosed with HCV infection for > 12 years. Management of HCV infection in low- and middle-income countries is hampered by high costs of medication. This is the first study to compare efficacy and safety of generic compared to original brand direct acting antivirals (DAAs) for hepatitis C treatment in Bahrain, where the prevalence of HCV infection is estimated to be 1.7% (1.39-2.21%). Overall, our study adds to the literature on the similarity in effectiveness in patients receiving both brand and generic formulations of DAAs for chronic hepatitis C.

- Citation: Abdulla M, Al Ghareeb AM, Husain HAHY, Mohammed N, Al Qamish J. Effectiveness and safety of generic and brand direct acting antivirals for treatment of chronic hepatitis C. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(34): 12566-12577

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i34/12566.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i34.12566

Over 71 million individuals live with hepatitis C virus (HCV) globally, equivalent to 1% of the world’s population[1]. Furthermore, approximately 5 million new cases of HCV were diagnosed in 2015[2]. HCV can present as an acute or a chronic infection. Acute HCV infection does not present with symptoms and up to 30% (15%–45%) of affected persons spontaneously eliminate the virus within 6 mo without medication[3]. However, roughly 70% of HCV infected persons develop chronic infection, and up to 30% of those will develop cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma within 20 years – eventually leading to almost 1 million deaths annually[3,4]. Achieving a sustained virologic response (SVR), where the HCV RNA levels remain undetectably low, has been associated with a reduction in liver-associated complications, improvement in health-related quality of life, and reduction in the need for liver transplantation among individuals with chronic hepatitis C[4-6].

Direct acting antivirals (DAAs) have revolutionized the treatment landscape for patients with chronic hepatitis C because they have been shown to demonstrate high SVR rates[7,8]. In response to this, the World Health Organization (WHO) proposed strategies for the elimination of HCV infection by 2030[9]. Achieving the HCV elimination strategy requires the diagnosis of 90% of those with hepatitis C, followed by treatment of 80% of those diagnosed – this will ultimately lead to an 80% reduction in new HCV infections, and a 65% reduction in HCV-associated mortality[8,9]. Furthermore, the WHO updated its chronic hepatitis C guidelines recommending treatment for all individuals diagnosed with HCV infection who are 12 years of age or older, irrespective of disease stage[9].

The uptake of DAAs in the management of HCV infection in several countries, especially in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), has been hampered by the high cost of medications[10]. Moreover, the increase in the rate of new HCV infections, the low rate of testing for HCV infection globally, and patent ownership rights and restrictions by brand name companies producing the DAAs, have hampered the production of their generic versions; and low rates of treatment in LMICs (harboring 72% of HCV burden) continue to threaten the attainment of the WHO HCV elimination goal[7]. With the increasing voluntary license permission being granted to companies producing generic DAAs by brand name manufacturers, the use of generic DAAs has substantially improved access to hepatitis C treatment in developing countries[11,12]. However, there are increasing concerns regarding the safety and efficacy of generic DAA formulations. A pharmacokinetic study has revealed similar bioequivalence between the generic and brand DAA formulations[13], and several real-world studies of generic DAAs and their systematic review have reported high SVR rates of 92%-98% in HCV infected patients irrespective of their genotype[7,14-15]. Despite these findings, comparative studies assessing the effectiveness and safety of generic vs brand DAA formulations for hepatitis C treatment are needed before its adoption, but only a few of these studies, carried out in India and Egypt, have been reported[16-18].

In Bahrain, the prevalence of HCV infection is estimated to be 1.7% (1.39%-2.21%)[2]. The predominant HCV genotype among Bahraini patients is type 1, followed by genotypes 3 and 4, and the lowest frequency is for genotype 2[19,20]. There is a real-world study of DAAs for hepatitis C treatment in Bahrain[21], but no study has compared the effectiveness of generic vs brand DAAs for hepatitis C treatment in the country. Therefore, the objective of this study was to compare the efficacy and safety of generic vs brand DAAs for chronic hepatitis C treatment in Bahrain.

This was a retrospective observational study involving 289 patients with a real time reverse transcrip

Patients’ enrolment in the study was in accordance with The European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) guidelines, 2016 and 2018[22,23]. All patients who were aged 18 years or over with a real-time RT-PCR diagnosis of chronic liver disease from HCV infection (i.e., based on the presence of HCV RNA for over 6 mo) were included in the study.

All the patients underwent full clinical assessment at baseline and after 12 wk of treatment. The baseline data collected included disease history and physical examination, complete blood count, prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time (PTT), INR, serum total bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase (ALP), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (gGT), albumin, creatinine, and serum HCV-RNA by real-time RT-PCR assay with lower limit of detection of 15 IU/mL (Abbott Real time HCV kits, m2000rt machine, Des Plaines, IL, 60018, United States). Abdominal ultrasound was carried out to detect the presence of liver cirrhosis and to exclude hepatocellular carcinoma and metastatic liver disease.

The patients were classified into two groups, brand and generic. The brand group included 149 patients who were treated with brand antiviral therapy according to EASL guidelines, 2016 and 2018. The generic group included 140 patients treated with generic DAAs according to EASL guidelines, 2016 and 2018[22,23].

Most of the patients who were treated with brand antiviral agents received Ombitasvir/Paritaprevir/ Ritonavir ± Dasabuvir ± Ribavirin [Omb/Par/Rit ± Das ± Rib; n = 44 (44.3%)], Sofosbuvir/Ledipasvir ± Ribavirin [Sof/Lep ± Rib; n = 55 (36.9%)], Sofosbuvir/Declatasvir ± Ribavirin [Sof/Dec ± Rib; n = 26 (17.4%)], and Sofosbuvir ± Ribavirin [Sof ± Rib; n = 2 (0.7%)]. These brand name agents included Sovaldi (Sofosbuvir), Harvoni (Sofosbuvir/Ledipasvir), Viekira Pak (Ombitasvir/Paritaprevir/Ritonavir/ Dasabuvir), Viekirax (Ombitasvir/Paritaprevir/Ritonavir), Daclinza (Daclatasvir), and Rebetol (Ribavirin), respectively. Of the patients treated with generic medications, 118 (84.3%) received Sofosbuvir/Daclatasvir ± Ribavirin [Sof/Dec ± Rib] while 22 (15.7%) received Sofosbuvir/Ledipasvir ± Ribavirin [Sof/Lep ± Rib]. These generic agents (all meant for use in Egypt) included Nucleobuvir (Sofosbuvir), Daclavirdine (Daclatasvir), Harvoni (Sofosbuvir/Ledipasvir), and Ribavirin (Ribavirin-Egypt). It should be noted that some of the generic medications used were produced by the same brand-name company at a lower price and for use only in LMICs such as Egypt.

The primary study endpoint was the proportion of patients having HCV-RNA below detectable limits 12 wk post treatment (SVR) within each patient group, and comparing the findings of the patients who received brand vs generic DAAs. We also assessed the proportion of patients who abandoned treatment due to adverse effects of the antiviral therapy. Treatment failure was defined as the presence of HCV-RNA above detectable limits in patients after 12 wk of having completed therapy, irrespective of the type of DAAs received. Further clinical and laboratory evaluation was carried out at 12 wk post treatment in order to compare the laboratory parameters at baseline and after treatment in each group.

Data analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (Version 24.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp, United States). The normality of continuous variables was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk’s test, and they are reported as the mean ± standard deviation (SD), or for non-normally distributed variables as median (interquartile range). Categorical variables are presented as frequencies and percentages, and were compared using the Chi-Square test. Independent samples t-test was used to compare continuous variables with a normal distribution, while Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare non-normal continuous data. Paired t-test was used to compare continuous paired-samples of laboratory parameters before and at the end of treatment for each group. Univariate and multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed to determine the predictors of not achieving SVR 12 wk post treatment. Not achieving SVR was the dependent variable, while the treatment group was the main independent variable. Known predictors of SVR and variables with a P value of < 0.2 in the univariate analysis were the criteria for inclusion in the final model. A P value (two-sided) < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

A total of 289 patients completed the study; 140 patients (48.4%) were treated with generic medications and 149 (51.6%) received brand medications. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1. There were no significant sex differences in the study participants, and except for the serum level of PTT and platelet count, there were no significant differences in the laboratory parameters explored between patients who received generic and brand medications (Table 1). Patients who received brand medications had a higher proportion of co-morbidities, such as cirrhosis (33.6 vs 10.0%), diabetes mellitus (31.5 vs 10.7%), dyslipidemia (15.4 vs 5.7%), hypertension (24.8 vs 14.3%), and sickle cell disease (6 vs 5.7%), while those who received generic medication had a higher proportion of co-morbidities like hypothyroidism (5.0 vs 1.3%) and human immunodeficiency virus infection (2.1 vs 0.7%). The baseline median (interquartile range) HCV RNA level was 717465 (356749-1489 361) IU/mL in patients who received brand medications compared to 712023.5 (331131-1820183) IU/mL in those who received generic medications (Mann-Whitney U test; P = 0.81).

| Variable | Generic, n (%) | Brand, n (%) | t (χ2)a statistic | P |

| Total | 140 | 149 | ||

| Age (yr) | 9.23a | 0.01 | ||

| < 40 | 52 (37.1) | 33 (22.1) | ||

| 40-65 | 73 (52.1) | 103 (69.1) | ||

| > 65 | 15 (10.7) | 13 (8.7) | ||

| Sex | 0.23a | 0.63 | ||

| Female | 59 (42.1) | 67 (45.0) | ||

| Male | 81 (57.9) | 82 (55.0) | ||

| Co-morbidities | 32.28a | < 0.001 | ||

| None | 65 (46.4) | 25 (16.8) | ||

| one to two | 61 (43.6) | 85 (57.0) | ||

| More than two | 14 (10.0) | 39 (26.2) | ||

| USD cirrhosis | 15.10a | < 0.001 | ||

| No | 113 (80.7) | 89 (59.7) | ||

| Yes | 27 (19.3) | 60 (40.3) | ||

| HCV genotype | 9.86a | 0.02 | ||

| 1 | 88 (62.9) | 109 (73.2) | ||

| 2 | 4 (2.9) | 2 (1.3) | ||

| 3 | 33 (23.6) | 16 (10.7) | ||

| 4 | 15 (10.7) | 22 (14.8) | ||

| WBC (× 109/L) ± SD | 6.26 ± 3.34 | 5.82 ± 2.15 | 1.37 | 0.17 |

| Haemoglobin (g/dL) ± SD | 12.50 ± 2.52 | 12.80 ± 2.12 | -1.1 | 0.27 |

| Platelets (× 109/L) ± SD | 232.35 ± 108.08 | 189.01 ± 95.48 | 3.62 | < 0.001 |

| PT (sec) ± SD | 14.11 ± 11.94 | 13.3 ± 1.88 | 0.8 | 0.43 |

| PTT (sec) ± SD | 24.16 ± 2.94 | 26.21 ± 3.79 | -5.1 | < 0.001 |

| INR ± SD | 1.08 ± 0.18 | 1.31 ± 2.22 | -1.2 | 0.23 |

| Creatinine (μmol/L) ± SD | 66.86 ± 21.07 | 89.68 ± 148.85 | -1.8 | 0.07 |

| Albumin (g/L) ± SD | 41.04 ± 5.11 | 38.81 ± 6.05 | 3.36 | 0.01 |

| Total bilirubin (μmol/L) ± SD | 17.68 ± 15.62 | 18.72 ± 18.26 | -0.52 | 0.6 |

| ALP (U/L) ± SD | 93.31 ± 43.54 | 102.02 ± 43.79 | -1.7 | 0.09 |

| ALT (U/L) ± SD | 71.66 ± 57.59 | 61.96 ± 41.47 | 1.65 | 0.1 |

| gGT(U/L) ± SD | 84.44 ± 109.99 | 101.76 ± 92.69 | -1.45 | 0.15 |

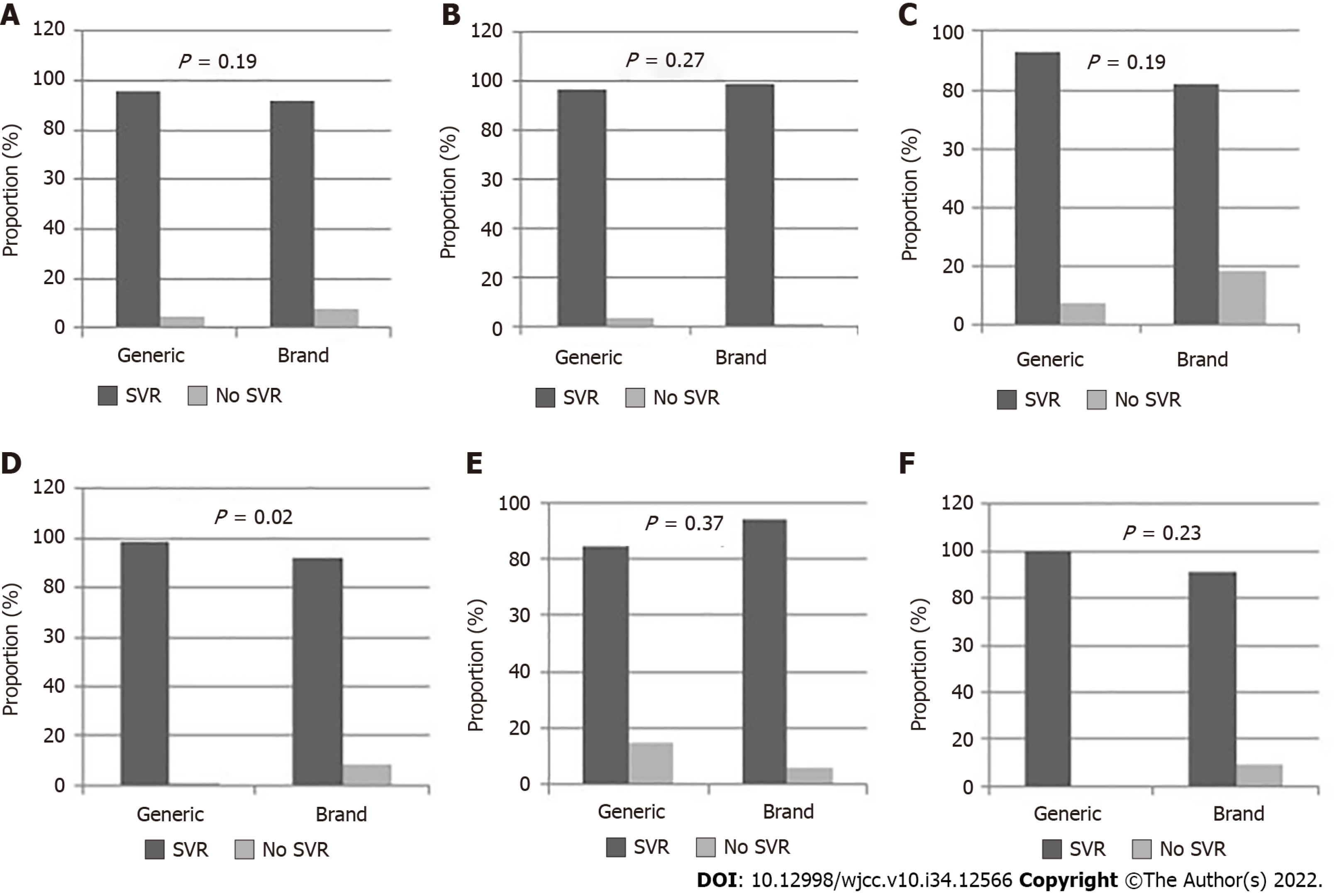

By 12 wk following treatment, SVR was achieved by 271 (93.8%) of the patients. Figure 1A-F summarizes the outcomes of treatment among patients treated with brand and generic medications and their subgroups. Of the patients who were treated with generic medications, 134 (95.7%) achieved SVR at 12 wk post treatment. In comparison, 137 (91.9%) of the patients who were treated with brand DAAs achieved SVR at 12 wk post treatment (Figure 1A; χ2 = 1.76, P = 0.19). In patients who received generic medications, 6 (4.3%) did not achieve SVR at 12 wk post treatment due to treatment failure, whereas for patients treated with brand medications, SVR was not achieved due to abandoning treatment for adverse effects in 7 (4.7%) patients, and to treatment failure in 5 (3.4%).

Among patients without liver cirrhosis (Figure 1B), 109 (96.5%) treated with generic medications and 88 (98.9%) treated with brand medications achieved SVR (P = 0.27). Similarly, among patients with cirrhosis (Figure 1C), there was no significant difference in the SVR rates between patients treated with brand and generic medications (P = 0.19). However, among patients with HCV genotype 1 (Figure 1D), 87 out of 88 patients (98.9%) treated with generic medications had SVR, compared to 100 of 109 (91.7%) patients who were treated with brand medications (P = 0.02). All patients with genotype 2, irrespective of the type of medication given, had SVR (100%). There was no significant difference in the SVR observed for patients with genotypes 3 and 4 according to the regimen received (Figure 1E and F).

Table 2 shows the predictors of not achieving SVR after 12 wk of treatment. In univariate analysis, having more than two co-morbidities and having ultrasound-diagnosed (USD) cirrhosis were significant determinants. On multivariable logistic regression analysis, being in the 40-65 years age group (odds ratio [OR]: 0.26, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.67-0.99), having USD cirrhosis (OR: 9.41, 95%CI: 2.47-35.84), and having HCV genotype 3 (OR: 3.56, 95%CI: 1.03–12.38) were significant independent predictors of not achieving SVR after 12 wk of treatment.

| Variable | No SVR, n (%) | Crude OR, (95%CI) | Adjusted OR, (95%CI) | Adjusted P |

| Age (yr) | ||||

| < 40 | 6 (7.1) | 1 | 1 | |

| 40-65 | 8 (4.5) | 0.63 (0.21-1.87) | 0.26 (0.67-0.99) | 0.049 |

| > 65 | 4 (14.3) | 2.19 (0.57-8.42) | 1.26 (0.23-6.96) | 0.79 |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 8 (4.8) | 1 | 1 | |

| Male | 12 (7.4) | 1.59 (0.58-4.36) | 3.0 (0.87-10.37) | 0.08 |

| Co-morbidities | ||||

| None | 2 (2.2) | 1 | 1 | |

| 0ne to two | 10 (6.8) | 3.24 (0.69-15.12) | 1.36 (0.22-8.38) | 0.74 |

| More than two | 6 (11.3) | 5.62 (1.09- 28.93) | 3.63 (0.52-25.49) | 0.19 |

| USD cirrhosis | ||||

| No | 5 (2.5) | 1 | 1 | |

| Yes | 13 (14.9) | 6.92 (2.39-20.10) | 9.41 (2.47-35.84) | 0.001 |

| HCV genotype | ||||

| 1 | 10 (4.9) | 1 | 1 | |

| 3 | 6 (12.2) | 2.69 (0.93-7.81) | 3.56 (1.03-12.38) | 0.044 |

| 4 | 2 (5.4) | 1.10 (0.23-5.25) | 0.69 (0.13-3.75) | 0.67 |

| DAC regimen | ||||

| Generic | 6 (4.3) | 1 | 1 | |

| Brand | 12 (8.1) | 1.96 (0.71-5.36) | 2.00 (0.57-7.04) | 0.28 |

| WBC (× 109/L) | 1.04 (0.89-1.21) | |||

| Haemoglobin (g/dL) | 1.14 (0.92-1.41) | |||

| Platelets (× 109/L) | 1.00 (0.96-1.01) | |||

| PT (sec) | 1.02 (0.95-1.05) | |||

| PTT (sec) | 1.12 (0.98-1.29) | |||

| INR | 0.99 (0.72-1.38) | |||

| Creatinine (μmol/L) | 1.00 (0.98-1.01) | |||

| Albumin (g/L) | 0.98 (0.90-1.06) | |||

| Total bilirubin (μmol/L) | 0.99 (0.96-1.03) | |||

| ALP (U/L) | 1.05 (0.99-1.02) | |||

| ALT (U/L) | 1.01 (1.00-1.02) | |||

| gGT(U/L) | 1.03 (1.00-1.06) |

Table 3 shows the predictors of not achieving SVR 12 wk post treatment in patients receiving only Sofosbuvir-based generic and brand medications. In univariate analysis, only having USD cirrhosis and having HCV genotype 3 were significant determinants. On multivariable logistic regression analysis, having USD cirrhosis (OR: 8.99, 95%CI: 1.83–44.16) and having HCV genotype 3 (OR: 4.44, 95%CI: 1.17-16.89) remained significant independent predictors of not achieving SVR 12 wk post treatment.

| Variable | No SVR, n (%) | Crude OR (95%CI) | Adjusted OR (95%CI) | Adjusted P |

| Age (yr) | ||||

| < 40 | 5 (7.5) | 1 | 1 | |

| 40-65 | 6 (4.5) | 0.58 (0.17-1.98) | 0.30 (0.07-1.35) | 0.12 |

| > 65 | 20 (9.1) | 1.24 (0.22-6.89) | 0.69 (0.08-5.81) | 0.73 |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 4 (4.3) | 1 | 1 | |

| Male | 9 (6.9) | 1.66 (0.49-5.55) | 2.33 (0.57-9.53) | 0.24 |

| Co-morbidities | ||||

| None | 2 (2.6) | 1 | 1 | |

| 0ne to two | 7 (6.3) | 2.47 (0.50-12.21) | 1.03 (0.14-7.61) | 0.98 |

| More than two | 4 (11.4) | 4.77 (0.83-27.43) | 3.45 (0.41-29.05) | 0.26 |

| USD cirrhosis | ||||

| No | 4 (2.6) | 1 | 1 | |

| Yes | 9 (13.2) | 5.76 (1.71-19.42) | 8.99 (1.83-44.16) | 0.007 |

| HCV genotype | ||||

| 1 | 6 (4.1) | 1 | 1 | |

| 3 | 6 (12.2) | 3.30 (1.01-10.77) | 4.44 (1.17-16.89) | 0.03 |

| 4 | 1 (3.8) | 0.95 (0.11-8.20) | 0.95 (0.10-9.45) | 0.96 |

| DAC regimen | ||||

| Generic | 6 (4.3) | 1 | 1 | |

| Brand | 7 (8.4) | 2.06 (0.67-6.34) | 1.42 (0.34-5.94) | 0.63 |

| WBC (× 109/L) | 0.98 (0.80-1.21) | |||

| Haemoglobin (g/dL) | 1.15 (0.89-1.48) | |||

| Platelets (× 109/L) | 1.00 (0.99-1.01) | |||

| PT (sec) | 1.02 (0.95-1.06) | |||

| PTT (sec) | 1.17 (1.00-1.37) | |||

| INR | 1.00 (0.72-1.38) | |||

| Creatinine (μmol/L) | 1.00 (0.97-1.03) | |||

| Albumin (g/L) | 0.97 (0.90-1.06) | |||

| Total bilirubin (μmol/L) | 0.99 (0.95-1.03) | |||

| ALP (U/L) | 1.01 (1.00-1.02) | |||

| ALT (U/L) | 1.01 (1.00-1.02) | |||

| gGT(U/L) | 1.03 (1.00-1.07) |

Table 4 shows the changes in the laboratory parameters at baseline and after treatment among patients treated with generic and brand medications. There was no significant difference in the WBC count before and after treatment among patients treated with generic medications (P = 0.15), but there was a significant increase in WBC among those treated with brand medications (P = 0.005). Treatment with both generic and brand medications were associated with a significant increase in serum albumin level (P < 0.001) and platelet count (P < 0.001). Similarly, treatment with both generic and brand medications were associated with a significant decline in serum total bilirubin (P < 0.05), serum ALT (P < 0.001), and gGT (P < 0.001). Generic medication use was associated with a significant reduction in serum ALP levels at the end of treatment (P < 0.001); however, treatment with brand medications was associated with an insignificant reduction in serum ALP levels (Table 4).

| Variable | Period | Generic, mean ± SD | P | Brand, mean ± SD | P |

| WBC (× 109/L) | wk 0 | 6.27 ± 3.34 | 0.15 | 5.82 ± 2.15 | 0.005 |

| EOT | 6.67 ± 3.62 | 6.13 ± 2.40 | |||

| Haemoglobin (g/dL) | wk 0 | 12.50 ± 2.52 | 0.17 | 12.81 ± 2.12 | 0.94 |

| EOT | 12.71 ± 2.44 | 12.81 ± 2.25 | |||

| Platelets (× 109/L) | wk 0 | 232.35 ± 108.1 | < 0.001 | 189.01 ± 95.48 | < 0.001 |

| EOT | 257.63 ± 113.11 | 210.85 ± 100.69 | |||

| PT (sec) | wk 0 | 14.11 ± 11.93 | 0.52 | 13.32 ± 1.88 | 0.91 |

| EOT | 13.31 ± 8.79 | 13.30 ± 1.91 | |||

| PTT (sec) | wk 0 | 24.16 ± 2.91 | 0.001 | 26.20 ± 3.79 | 0.22 |

| EOT | 23.14 ± 4.25 | 25.90 ± 3.22 | |||

| INR | wk 0 | 1.08 ± 0.18 | 0.7 | 1.31 ± 2.22 | 0.31 |

| EOT | 1.11 ± 0.87 | 1.12 ± 0.17 | |||

| Creatinine (μmol/L) | wk 0 | 66.86 ± 21.07 | 0.05 | 89.68 ± 148.85 | 0.55 |

| EOT | 70.50 ± 31.94 | 92.05 ± 138.93 | |||

| Albumin (g/L) | wk 0 | 41.04 ± 5.11 | < 0.001 | 38.82 ± 6.05 | < 0.001 |

| EOT | 42.78 ± 5.46 | 40.90 ± 5.48 | |||

| Total bilirubin (μmol/L) | wk 0 | 17.68 ± 15.62 | < 0.001 | 18.72 ± 18.26 | 0.004 |

| EOT | 14.30 ± 12.64 | 15.14 ± 13.74 | |||

| ALP (U/L) | wk 0 | 93.31 ± 43.55 | < 0.001 | 102.02 ± 43.79 | 0.18 |

| EOT | 77.32 ± 32.65 | 94.79 ± 73.56 | |||

| ALT (U/L) | wk 0 | 71.66 ± 57.59 | < 0.001 | 61.96 ± 41.47 | < 0.001 |

| EOT | 27.09 ± 33.56 | 29.09 ± 24.58 | |||

| gGT(U/L) | w 0 | 84.44 ± 109.98 | < 0.001 | 101.76 ± 92.69 | < 0.001 |

| EOT | 43.48 ± 62.65 | 50.64 ± 53.37 |

The adoption of a new low-cost generic DAA therapy for the treatment of chronic HCV infection has remained a game changer for several national treatment programs as it has improved access to treatment and has provided significant progress towards the elimination of HCV. In most countries, generic formulations are required to undergo pharmaco-equivalence studies[9,12] and are therefore required to demonstrate a similar rate of absorption and bioavailability compared to the original brand drug before its approval for use. Several studies carried out in multiple countries have shown that generic and brand DAAs have similar bioequivalence[13,24]. Several studies have revealed the real-life effectiveness of generic DAAs[7,14,15], but only a few studies have assessed their clinical efficacy compared to the original brand DAAs. This study is a comparative assessment of chronic hepatitis C patients treated with either brand or generic DAAs. Although we did not randomize the study patients, most of the baseline laboratory tests and viral load did not significantly differ between patients treated with generic or brand DAAs. However, the patients significantly differed in their age group, HCV genotype, and number of co-morbidities including the proportion with USD cirrhosis.

In this study, we compared the safety and efficacy of generic vs brand DAAs for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C. The study findings revealed that the generic DAAs used were very effective with an SVR rate of 95.7% compared with 91.9% in patients receiving brand DAAs. Our findings are generally consistent with the findings of other studies. In Argentina, Marciano et al[25] compared treatment with generic or brand Sofosbuvir-based therapy for 321 patients with chronic hepatitis C, of whom 91% had cirrhosis. The study revealed an SVR rate of 91% among patients receiving brand and 89% among those receiving generic Sofosbuvir-based regimen. In Egypt, two studies among patients with chronic hepatitis C revealed SVR rates of 98.2%-100% among patients receiving generic DAAs compared with rates of 98.1%-99% in those receiving brand DAAs[17,18]. In India, Tang et al[16] carried out a non-randomized comparative study among 66 patients with chronic hepatitis C. SVR rates were 72.4% vs 75.7% among patients treated with generic vs brand DAAs. The lower SVR rates in the studies from Argentina and India compared to ours may be due to a higher proportion of patients with cirrhosis, and some of their patients were previously treated cases who had treatment failure[16,25]. Overall, our study adds to the literature on the similarity in effectiveness in patients receiving both brand and generic formulations of DAAs for chronic hepatitis C.

Being a middle-aged patient, having USD cirrhosis, and having genotype 3 were all predictors of not achieving SVR. Middle-aged patients were 74% less likely to achieve SVR while patients with cirrhosis were 9.4 times less likely to achieve SVR, and patients with HCV genotype 3 were almost 4 times less likely to do so. Furthermore, our analysis revealed that receiving brand or generic DAAs was not an independent risk factor for not achieving SVR. Moreover, when we restricted our analysis to patients treated with Sofosbuvir-based brand and generic regimens, our study revealed that having cirrhosis and genotype 3 were the independent predictors of not achieving SVR. A previous study in the same setting using brand DAAs for hepatitis C treatment revealed that having cirrhosis at baseline was the only risk factor for not achieving SVR [21]. The findings of this study indicate that adequate care and attention need to be given during treatment of patients with cirrhosis and genotype 3 HCV in our setting. Another study found that having positive HCV RNA at 4 wk post treatment was a risk factor for not achieving SVR[17]. In the present study, we did not assess the level of HCV RNA at 4 wk post treatment. This should be considered in future studies.

In terms of safety, this study revealed that 4.3% of HCV infected patients treated with generic DAAs had treatment failure compared with 3.4% among patients who received brand DAAs. None of the patients who received generic DAAs abandoned treatment due to adverse drug reaction/effects while 4.7% of those receiving brand DAAs did. Considering intention-to-treat analysis, although the proportion of patients with a poor outcome was higher among patients treated with brand medications, the difference was not statistically significant. Similar findings were documented by other investigators and this suggests that the safety profile of both generic and brand DAAs for HCV infection treatment are good. Both the generic and brand DAA formulations resulted in significant changes in the level of serum transaminases and hemoglobin level, and this is consistent with findings of previous studies involving brand or generic DAAs[26-30]. Total bilirubin substantially decreased at 12 wk post treatment[17,26,27,30,30]. ALP, ALT, and gGT all substantially declined at 12 wk post treatment when compared to baseline values in both groups in accordance with previously published reports.

This study has some limitations. This was a non-randomized retrospective observational clinical study from a single center. Not all the patients received the same type of brand or generic DAA formulation, which might have accounted for minor differences in the treatment outcome. The type of DAA medication given to the patients was based on the EASL guidelines at the time of enrolment[22,23]. Another important limitation is that, although the majority of our patients were treatment naïve, we do not have data on the proportion of previously treated hepatitis C patients included in this analysis, which might have affected the treatment outcomes[16-18]. This should be considered during further studies in our setting. Moreover, other factors that might have influenced the treatment outcome is the choice of the DAA medication used. In our study, the choice of DAA regimen used was physician driven, i.e., based on the physicians’ interest in treating the greatest number of patients effectively considering the best available evidence, as well as the most effective medications according to the patients’ profile at a reduced cost.

This study shows that generic and brand DAAs demonstrated comparable effectiveness in the treatment of chronic hepatitis C patients, were well tolerated, and were equally effective in improving biochemical markers of hepatic inflammation. Therefore, generic DAAs could revolutionize the treatment of hepatitis C – providing access to treatment for millions of people infected with HCV. Closer monitoring should be given to HCV infected patients with HCV genotype 3 and cirrhosis during treatment.

Direct acting antiviral (DAA) agents have revolutionized the treatment of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection because they are highly effective. However, brand DAA agents are very expensive and unaffordable to many patients who need them. Generic versions of the DAA agents are being developed to address this challenge but research on whether their effectiveness is comparable to brand DAA agents are limited.

Data on the clinical efficacy of generic DAA agents for chronic HCV infection treatment is rare in Bahrain.

This study evaluated the effectiveness and safety of generic compared to brand DAA agents for chronic HCV infection treatment.

In this observational study, 149 patients were enrolled and treated with brand DAA agents (brand group), and another 140 patients were enrolled and treated with generic versions of DAA agents (generic group) over a two-year period. The primary outcomes included sustained virologic response after 12 wk of treatment and its determinants.

In general, there was no significant differences in the treatment outcome of patients who received brand vs generic DAA agents in terms of their sustained virologic response after 12 wk of treatment. Both generic and brand DAAs showed marked improvement in liver function evidenced by a substantial reduction in serum alanine and aspartate aminotransferase levels and total bilirubin levels. Overall, patients who had cirrhosis and HCV genotype 3 were significantly less likely to achieve sustained virologic response after 12 wk of treatment.

Generic DAA agents have similar clinical efficacy and safety levels compared to brand DAA agents in the treatment of chronic HCV infection. They also show similarity in their improvement of hepatic function in these patients.

Further studies are needed to better evaluate the long-term efficacy and safety of generic direct acting antiviral (DAA) agents in previously treated hepatitis C virus (HCV) infected patients and in patients with cirrhosis and HCV genotype 3.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Bahrain

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: El Kassas M, Egypt; El-Bendary M, Egypt; Lo SY, Taiwan; Metawea MI, Egypt S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | World Health Organization. Global hepatitis report 2017. World Health Organization; Geneva 2017. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241565455. |

| 2. | GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392:1789-1858. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9354] [Cited by in RCA: 8390] [Article Influence: 1198.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 3. | World Health Organization. Hepatitis C fact sheet. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hepatitis-c (accessed 20/02/2022). |

| 4. | Nahon P, Bourcier V, Layese R, Audureau E, Cagnot C, Marcellin P, Guyader D, Fontaine H, Larrey D, De Lédinghen V, Ouzan D, Zoulim F, Roulot D, Tran A, Bronowicki JP, Zarski JP, Leroy V, Riachi G, Calès P, Péron JM, Alric L, Bourlière M, Mathurin P, Dharancy S, Blanc JF, Abergel A, Serfaty L, Mallat A, Grangé JD, Attali P, Bacq Y, Wartelle C, Dao T, Benhamou Y, Pilette C, Silvain C, Christidis C, Capron D, Bernard-Chabert B, Zucman D, Di Martino V, Thibaut V, Salmon D, Ziol M, Sutton A, Pol S, Roudot-Thoraval F; ANRS CO12 CirVir Group. Eradication of Hepatitis C Virus Infection in Patients With Cirrhosis Reduces Risk of Liver and Non-Liver Complications. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:142-156.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 420] [Cited by in RCA: 401] [Article Influence: 50.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ferrarese A, Germani G, Gambato M, Russo FP, Senzolo M, Zanetto A, Shalaby S, Cillo U, Zanus G, Angeli P, Burra P. Hepatitis C virus related cirrhosis decreased as indication to liver transplantation since the introduction of direct-acting antivirals: A single-center study. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:4403-4411. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Morgan RL, Baack B, Smith BD, Yartel A, Pitasi M, Falck-Ytter Y. Eradication of hepatitis C virus infection and the development of hepatocellular carcinoma: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:329-337. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 631] [Cited by in RCA: 653] [Article Influence: 54.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Perazzo H, Castro R, Luz PM, Banholi M, Goldenzon RV, Cardoso SW, Grinsztejn B, Veloso VG. Effectiveness of generic direct-acting agents for the treatment of hepatitis C: systematic review and meta-analysis. Bull World Health Organ. 2020;98:188-197K. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Falade-Nwulia O, Suarez-Cuervo C, Nelson DR, Fried MW, Segal JB, Sulkowski MS. Oral Direct-Acting Agent Therapy for Hepatitis C Virus Infection: A Systematic Review. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166:637-648. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 497] [Cited by in RCA: 551] [Article Influence: 68.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | World Health Organization. Guidelines for the Care and Treatment of Persons Diagnosed With Chronic Hepatitis C Virus Infection 2018. Available from: www.who.int/hepatitis/publications/hepatitis-c-guidelines-2018/en (accessed 20/02/2022). |

| 10. | Iyengar S, Tay-Teo K, Vogler S, Beyer P, Wiktor S, de Joncheere K, Hill S. Prices, Costs, and Affordability of New Medicines for Hepatitis C in 30 Countries: An Economic Analysis. PLoS Med. 2016;13:e1002032. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 185] [Cited by in RCA: 185] [Article Influence: 20.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Baumert TF, Berg T, Lim JK, Nelson DR. Status of Direct-Acting Antiviral Therapy for Hepatitis C Virus Infection and Remaining Challenges. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:431-445. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 24.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | World Health Organization. Progress report on access to hepatitis C treatment: focus on overcoming barriers in low and middle income countries 2018; Geneva, Switzerland. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/260445. |

| 13. | Hill A, Tahat L, Mohammed MK, Tayyem RF, Khwairakpam G, Nath S, Freeman J, Benbitour I, Helmy S. Bioequivalent pharmacokinetics for generic and originator hepatitis C direct-acting antivirals. J Virus Erad. 2018;4:128-131. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Gupta S, Rout G, Patel AH, Mahanta M, Kalra N, Sahu P, Sethia R, Agarwal A, Ranjan G, Kedia S, Acharya SK, Nayak B, Shalimar. Efficacy of generic oral directly acting agents in patients with hepatitis C virus infection. J Viral Hepat. 2018;25:771-778. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Zeng QL, Xu GH, Zhang JY, Li W, Zhang DW, Li ZQ, Liang HX, Li CX, Yu ZJ. Generic ledipasvir-sofosbuvir for patients with chronic hepatitis C: A real-life observational study. J Hepatol. 2017;66:1123-1129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Tang L, Kamat M, Shukla A, Vora M, Kalal C, Kottilil S, Shah S. Comparative Antiviral Efficacy of Generic Sofosbuvir versus Brand Name Sofosbuvir with Ribavirin for the Treatment of Hepatitis C. Interdiscip Perspect Infect Dis. 2018;2018:9124604. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Abozeid M, Alsebaey A, Abdelsameea E, Othman W, Elhelbawy M, Rgab A, Elfayomy M, Abdel-Ghafar TS, Abdelkareem M, Sabry A, Fekry M, Shebl N, Rewisha E, Waked I. High efficacy of generic and brand direct acting antivirals in treatment of chronic hepatitis C. Int J Infect Dis. 2018;75:109-114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | El-Nahaas SM, Fouad R, Elsharkawy A, Khairy M, Elhossary W, Anwar I, Abdellatif Z, Maher RM, Bekheet N, Esmat G. High sustained virologic response rate using generic directly acting antivirals in the treatment of chronic hepatitis C virus Egyptian patients: single-center experience. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;30:1194-1199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Abdulla MA, Murad EA, Aljenaidi HA, Aljowder DR, Aljeeran OI, Farid E, Al Qamish JR. Interrelationship of hepatitis C virus genotypes with patient characteristics in Bahrain. Hepat Med. 2017;9:7-11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Janahi EM, Al-Mannai M, Singh H, Jahromi MM. Distribution of Hepatitis C Virus Genotypes in Bahrain. Hepat Mon. 2015;15(12):e30300. DOI: 10.5812/hepatmon.30300. |

| 21. | Abdulla M, Ali H, Nass H, Khamis J, AlQamish J. Efficacy of direct-acting antiviral therapy for hepatitis C viral infection. Real-life experience in Bahrain. Hepat Med. 2019;11:69-78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Recommendations on Treatment of Hepatitis C 2016. J Hepatol. 2017;66:153-194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 821] [Cited by in RCA: 805] [Article Influence: 100.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Recommendations on Treatment of Hepatitis C 2018. J Hepatol. 2018;69:461-511. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1281] [Cited by in RCA: 1211] [Article Influence: 173.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Bendas ER, Rezk MR, Badr KA. Drug Interchangeability of Generic and Brand Products of Fixed Dose Combination Tablets of Sofosbuvir and Ledipasvir (400/90 mg): Employment of Reference Scaled Average Bioequivalence Study on Healthy Egyptian Volunteers. Clin Drug Investig. 2018;38:439-448. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Marciano S, Haddad L, Reggiardo MV, Peralta M, Vistarini C, Marino M, Descalzi VI, D'Amico C, Figueroa Escuti S, Gaite LA, Perez Ravier R, Longo C, Borzi SM, Galdame OA, Bessone F, Fainboim HA, Frías S, Cartier M, Gadano AC. Effectiveness and safety of original and generic sofosbuvir for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C: A real world study. J Med Virol. 2018;90:951-958. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Deterding K, Höner Zu Siederdissen C, Port K, Solbach P, Sollik L, Kirschner J, Mix C, Cornberg J, Worzala D, Mix H, Manns MP, Cornberg M, Wedemeyer H. Improvement of liver function parameters in advanced HCV-associated liver cirrhosis by IFN-free antiviral therapies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;42:889-901. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Raschzok N, Schott E, Reutzel-Selke A, Damrah I, Gül-Klein S, Strücker B, Sauer IM, Pratschke J, Eurich D, Stockmann M. The impact of directly acting antivirals on the enzymatic liver function of liver transplant recipients with recurrent hepatitis C. Transpl Infect Dis. 2016;18:896-903. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Elsharkawy A, Eletreby R, Fouad R, Soliman Z, Abdallah M, Negm M, Mohey M, Esmat G. Impact of different sofosbuvir based treatment regimens on the biochemical profile of chronic hepatitis C genotype 4 patients. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;11:773-778. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Mohamed MS, Hanafy AS, Bassiony MAA, Hussein S. Sofosbuvir and daclatasvir plus ribavirin treatment improve liver function parameters and clinical outcomes in Egyptian chronic hepatitis C patients. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;29:1368-1372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Lourenço MS, Zitelli PMY, Cunha-Silva M, Oliveira AIN, Oliveira CP, Sevá-Pereira T, Carrilho FJ, Pessoa MG, Mazo DF. Direct-acting antivirals for chronic hepatitis C treatment: The experience of two tertiary university centers in Brazil. World J Hepatol. 2022;14:195-208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |