Published online Nov 26, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i33.12416

Peer-review started: September 3, 2022

First decision: September 26, 2022

Revised: October 13, 2022

Accepted: October 24, 2022

Article in press: October 24, 2022

Published online: November 26, 2022

Processing time: 80 Days and 20.2 Hours

Herbal medicine has a long history of use in the prevention and treatment of disease and is becoming increasingly popular globally. However, there are also widespread concerns about its safety. Among them, the cardiotoxicity of aconitine has been described.

We report a case of a 61-year-old male with aconitine poisoning presenting with malignant arrhythmia and severe cardiogenic shock, which was successfully managed with aggressive advanced life support and heart transplantation.

This is the first case wherein in vivo cardiac pathology was obtained, confirming that aconitine caused acute myocardial necrosis.

Core Tip: Aconitine poisoning can cause severe cardiotoxicity. In this patient, aconitine poisoning led to life-threatening ventricular arrhythmia and cardiogenic shock, ultimately requiring a heart transplantation as a cure.

- Citation: Liao YP, Shen LH, Cai LH, Chen J, Shao HQ. Acute myocardial necrosis caused by aconitine poisoning: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(33): 12416-12421

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i33/12416.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i33.12416

Aconitine, a diester alkaloid with the chemical formula C34H47NO11, is the main toxic component present in plants such as Aconitum carmichaelii, Radix Aconiti kusnezoffii, and A. napellus. Aconitum, a traditional medical herb, is believed to have analgesic, anti-inflammatory, and circulatory enhancing effects[1,2]. However, it has been shown to have severe cardiotoxicity[3]. We report a case of aconitine poisoning presenting with life-threatening ventricular arrhythmia and cardiogenic shock requiring the assistance of ventilators, bedside blood purification device, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), and intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) equipment. In this case, heart transplantation was required to save the life of the patient, and the in vivo cardiac pathology results indicated severe myocardial necrosis due to aconitine poisoning.

A 61-year-old male was admitted to the hospital due to dizziness and vomiting.

Five hours prior to arrival, he consumed about 40 mL of homemade herbal medicinal wine due to back pain. Approximately 10 min later, he developed dizziness and severe, non-projectile vomiting.

The patient had been in good health in the past.

He had occasionally consumed homemade Chinese herbal medicinal wine for back pain in the past month, about 20 mL each time, according to the family.

On admission, the patient was unconscious, and the main artery pulse disappeared. The heart sound was not heard, and the blood pressure was 0 mmHg.

Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry showed blood and urine aconitine concentrations of 65.6 μg/mL and 1064.2 μg/mL, respectively.

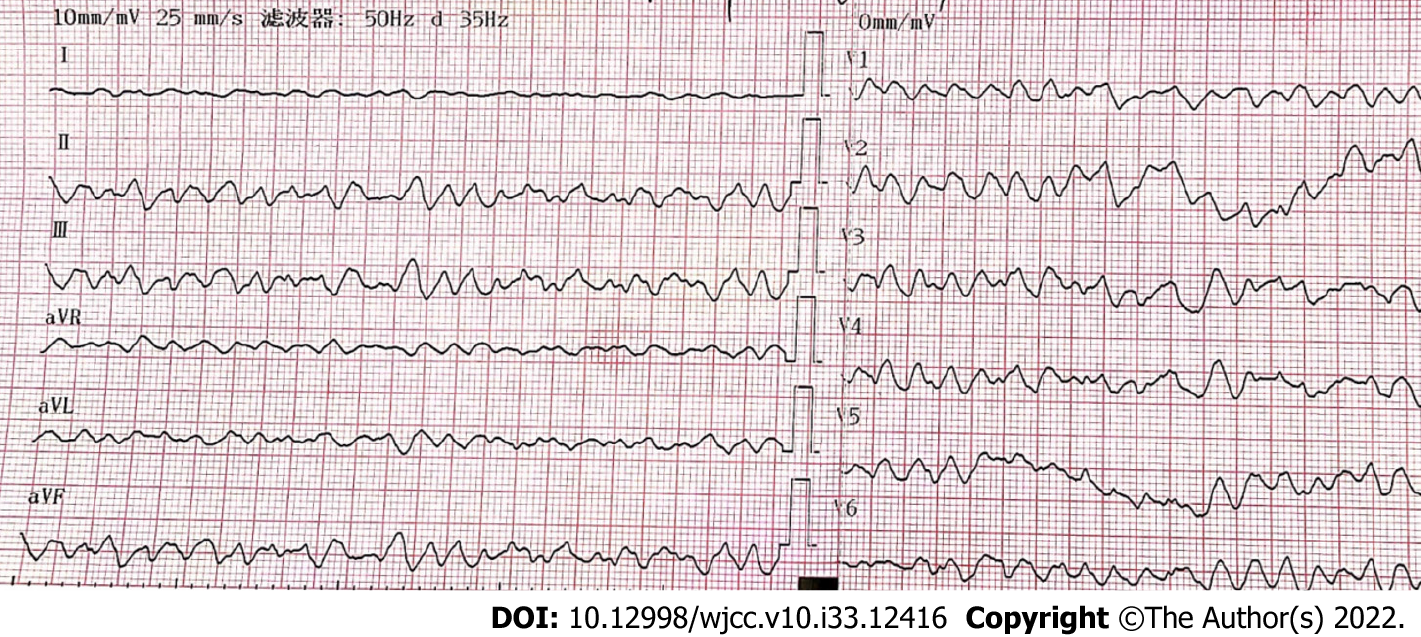

Upon arrival at the hospital, a complete electrocardiogram (ECG) showed ventricular fibrillation (Figure 1), and cardiac arrest occured afterward.

Given the patient’s history and blood panel results, he was diagnosed with acute aconitine poisoning.

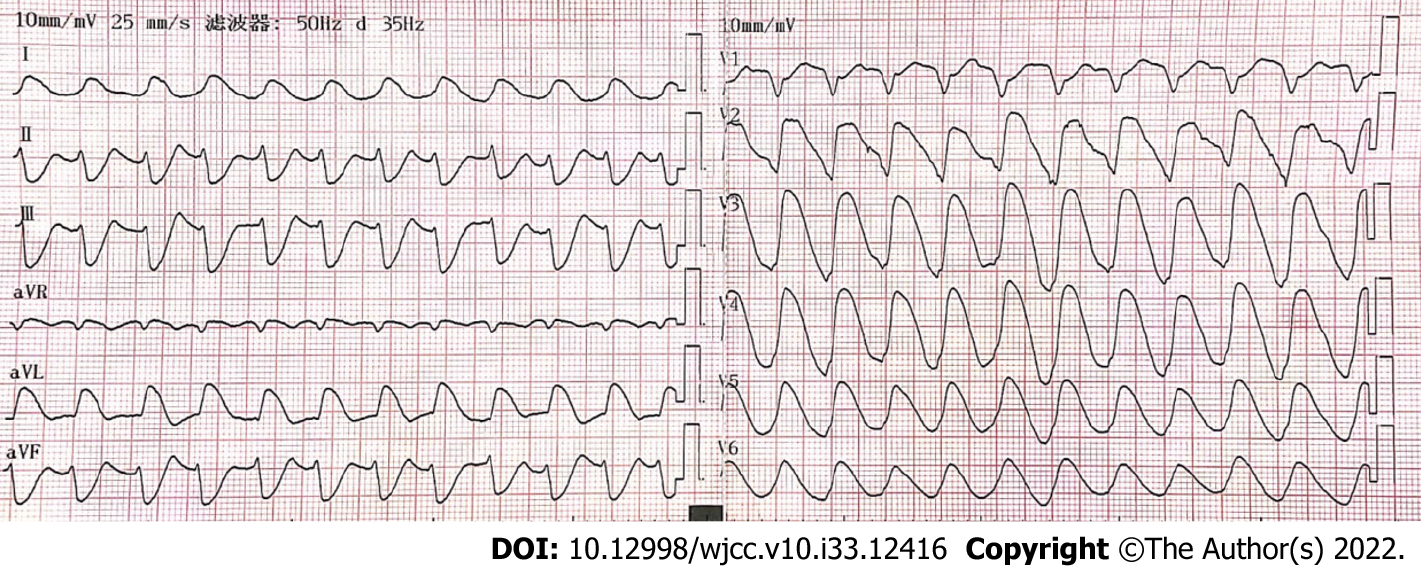

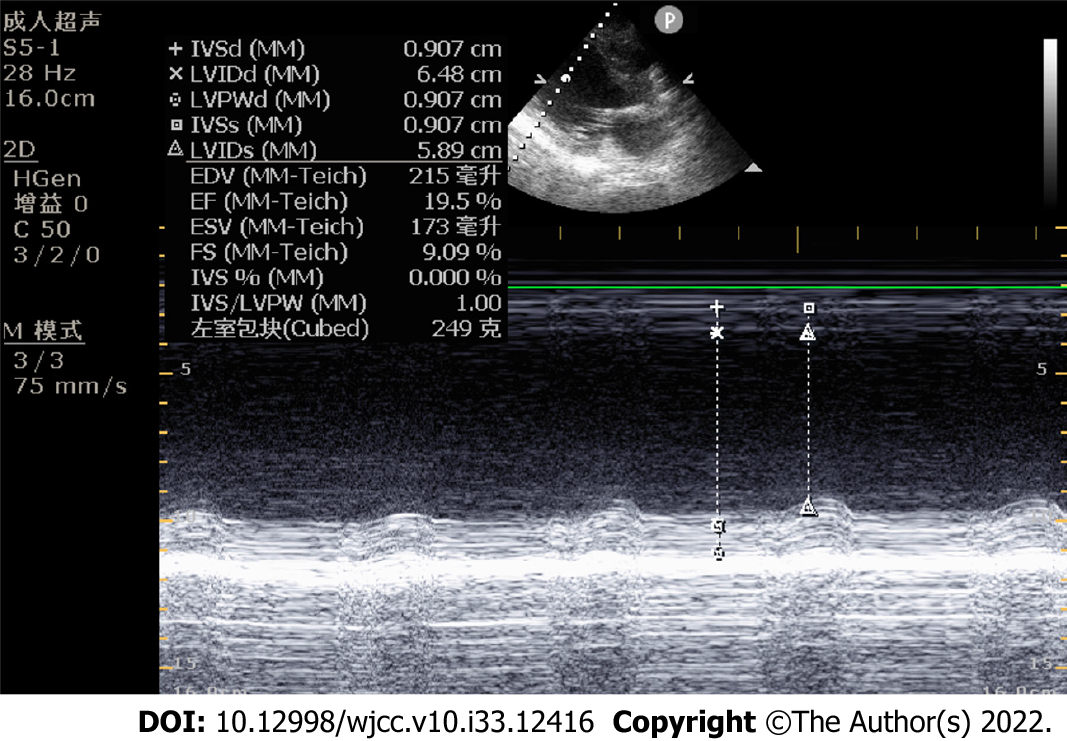

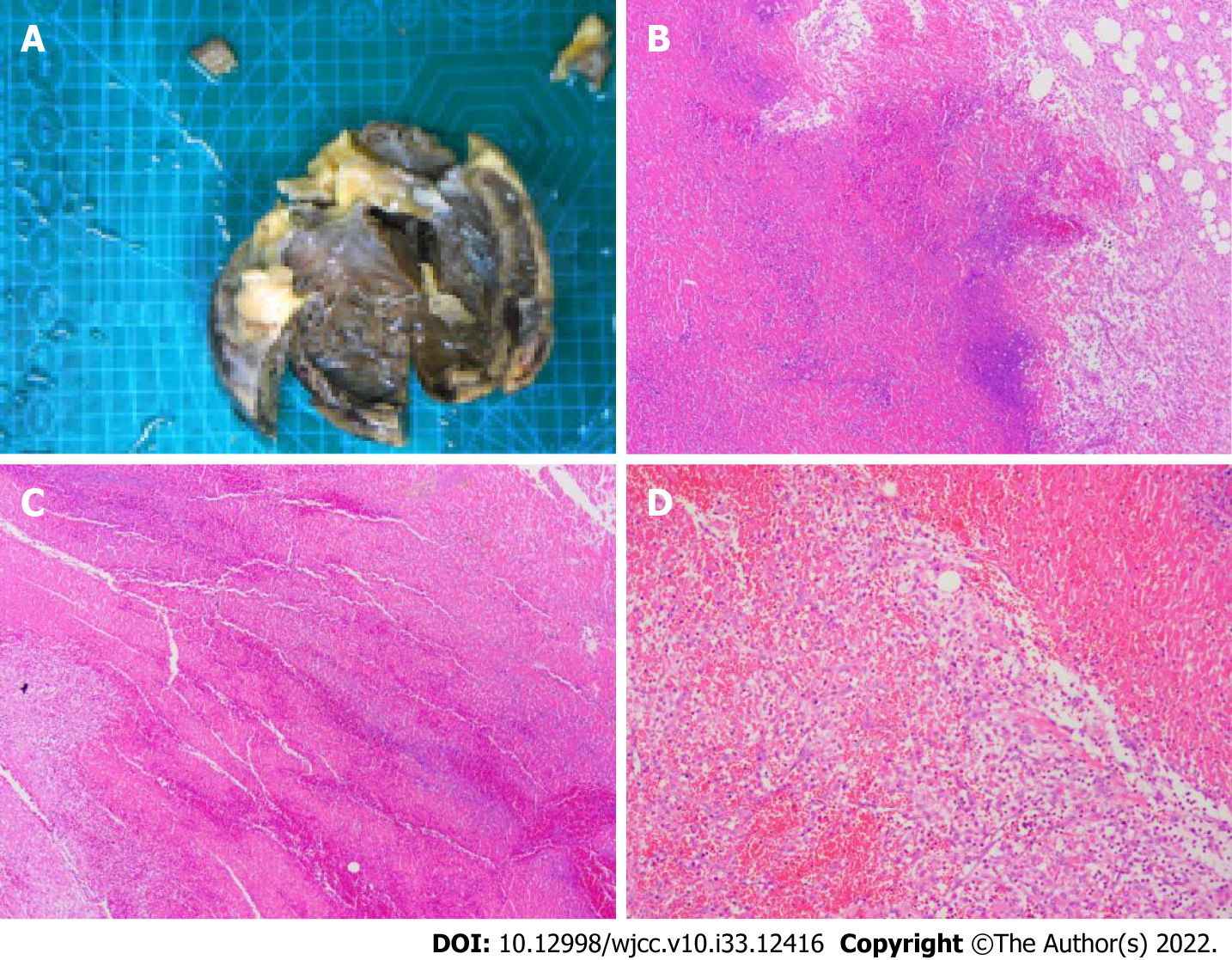

The patient was treated with external electric defibrillation (200 J), chest compressions, endotracheal intubation, ventilator-assisted ventilation, and intravenous epinephrine. After 5 min, the patient’s heartbeat recovered, and the ECG showed rapid ventricular tachycardia (Figure 2). Amiodarone (150 mg) was slowly administered intravenously for 15 min, followed by a continuous infusion at 1 mg/min. Considering that the patient’s hypotension was refractory despite the high-dose norepinephrine (> 1 μg/kg/min) and that he had malignant arrhythmia and cardiogenic shock, adjuvant support therapy with venoarterial ECMO (VA-ECMO) was performed within 60 min of arrival at the hospital after obtaining consent from the patient’s family. After admission, acute neurological events were ruled out by complete head computed tomography, and acute coronary syndrome was ruled out by coronary angiography. On the same day, complete toxicologic analyses of the blood and urine were performed. Blood and urine aconitine concentrations were 65.6 μg/mL and 1064.2 μg/mL, respectively. Daily blood purification therapy was administered to the patient from days 1 to 4 of admission. After treatment, the blood aconitine concentration decreased to 0 μg/mL on day 4, and the urine aconitine concentration decreased to 0.8 μg/mL on day 11 (Table 1). Additionally, the patient was given glucocorticoids (methylprednisolone; 200 mg for 4 d, 120 mg for 3 d, 40 mg for 2 d), γ-globulin (20 g for 3 d), and symptomatic treatment such as bedside hemofiltration and maintenance of internal environment stability. An IABP was used for cardiac assistance on day 1 of admission, and a conventional dose of levosimendan therapy was initiated on day 5 and day 12. However, the patient’s cardiac function did not improve. Multiple cardiac ultrasound indicated left ventricular enlargement with severe diffuse hypokinesis of the left ventricular wall. On day 18 of admission, cardiac ultrasound revealed ejection fraction of 19.5% (Figure 3). The patient had difficulty in removing the ECMO and IABP. Hence, he underwent heart transplantation 21 d later. In vivo cardiac pathology suggested dilatation of the left ventricle, total necrosis of part of the left ventricular wall accompanied by hemorrhage, partial myocardial necrosis of the ventricular septum, hyperplasia of fibrous granulation tissue, and some infiltration of neutrophils, lymphocytes, plasma cells, and histocytes. Additionally, edema and degeneration of a few cardiomyocytes in the right ventricle were observed (Figure 4).

| AC | Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 4 | Day 5 | Day 11 |

| Blood AC (ng/mL) | 65.6 | 12.7 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Urine AC (ng/mL) | 1064.2 | 1021.6 | 876.5 | 264.7 | 0.8 |

The patient was cured and discharged 3 wk after heart transplantation. The patient has been followed up for 1 year after discharge and has been in good living condition, with no obvious abnormalities on cardiac ultrasound or electrocardiogram.

Globally, herbal medicine is used for many medical problems. With increasingly widespread communication, aconitine cardiotoxicity has been reported worldwide despite its analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects. Yeih et al[4] reported a case of aconitine-induced life-threatening ventricular tachyarrhythmia that was successfully restored to normal sinus rhythm with amiodarone. Moritz et al[5] also described a case of acute arrhythmia caused by the ingestion of three homemade aconitine capsules, in which the half-life of aconitine in humans was calculated to be 3 h. Bicker et al[6] reported three cases of death resulting from aconitine poisoning and found that the aconitine concentration was significantly higher in heart blood than in peripheral blood.

Aconitine is highly toxic, and the heart is the main target organ of poisoning, which leads to death mainly by ventricular arrhythmia and cardiac arrest[7,8]. To the best of our knowledge, no exact lethal dose of aconitine has been reported to date. In one case of mortality reported in the literature, the patient’s antemortem aconitine blood concentration was 39.1 ng/mL, and the postmortem urine concentration was 67.4 ng/mL[9]. In our case, the aconitine concentration in the blood and urine was significantly higher than that reported in the aforementioned study, which is considered to be associated with the accumulation of oral aconitine from herbal medicinal wine that was repeatedly ingested 1 mo before the patient’s visit. Moreover, the patient developed acute malignant arrhythmia and cardiac arrest and was eventually resuscitated successfully. Organ support technologies such as ECMO, IABP, and bedside blood purification provided a good bridging effect. However, it has also been reported that the aconitine blood concentration does not fully correlate with symptoms or ECG results due to different times of arrival at the hospital and individual physiological differences[10]. Therefore, close monitoring and timely and effective means of support for patients with aconitine poisoning are essential.

Several fundamental studies have explored the mechanism of aconitine-induced cardiotoxicity, but the exact mechanism has not been fully understood. It has been shown that aconitine increases the peak Na+ current (iNa) by accelerating Na+ channel activation and Na+/K+ pump inhibition, thereby inducing various ventricular arrhythmias in guinea pigs[11]. In addition, aconitine also significantly exacerbates Ca2+ overload, leading to arrhythmia, and ultimately promotes the development of apoptosis through the phosphorylation of P38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)[12]. Studies have also found that aconitine inhibits the expression of TnT and Bcl-2 and promotes the expression of caspase 3 and Bax in zebrafish embryonic cardiomyocytes[13]. In summary, studies on the mechanism of aconitine-induced cardiotoxic effects have mainly focused on interactions with ion channels, induction of cytotoxic damage, and epigenetic and transcriptional regulation[8]. Unfortunately, no specific antidote for aconitine poisoning has been found. In this case, we tried to use immunoglobulin and glucocorticoids for immune anti-inflammatory therapy. However, the results were poor, and the patient had massive myocardial necrosis and irreversible cardiac pump failure. Fortunately, the patient was eventually cured by heart transplantation, and we obtained the first in vivo cardiac pathology specimen of aconitine poisoning. With this pathological result, we found that aconitine caused acute myocardial necrosis, which is of great benefit to our understanding of the mechanism of aconitine poisoning. At the same time, this case also showed that VA-ECMO played an important role as effective support for circulatory failure in cardiogenic shock, cardiac arrest, and refractory ventricular arrhythmias caused by poisoning, providing healthcare providers ample time for subsequent diagnosis and treatment.

Aconitine poisoning can cause acute myocardial necrosis. VA-ECMO played an important role in maintaining the patients’ condition until heart transplantation.

All of the authors would like to express their gratitude to the patient.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Substance abuse

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Duan H, China; Walusansa A, Uganda S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Jiang H, Zhang Y, Wang X, Meng X. An Updated Meta-Analysis Based on the Preclinical Evidence of Mechanism of Aconitine-Induced Cardiotoxicity. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:900842. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Khan H, Nabavi SM, Sureda A, Mehterov N, Gulei D, Berindan-Neagoe I, Taniguchi H, Atanasov AG. Therapeutic potential of songorine, a diterpenoid alkaloid of the genus Aconitum. Eur J Med Chem. 2018;153:29-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Coulson JM, Caparrotta TM, Thompson JP. The management of ventricular dysrhythmia in aconite poisoning. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2017;55:313-321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Yeih DF, Chiang FT, Huang SK. Successful treatment of aconitine induced life threatening ventricular tachyarrhythmia with amiodarone. Heart. 2000;84:E8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Moritz F, Compagnon P, Kaliszczak IG, Kaliszczak Y, Caliskan V, Girault C. Severe acute poisoning with homemade Aconitum napellus capsules: toxicokinetic and clinical data. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2005;43:873-876. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Bicker W, Monticelli F, Bauer A, Roider G, Keller T. Quantification of aconitine in post-mortem specimens by validated liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry method: three case reports on fatal 'monkshood' poisoning. Drug Test Anal. 2013;5:753-762. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Li H, Liu L, Zhu S, Liu Q. Case reports of aconite poisoning in mainland China from 2004 to 2015: A retrospective analysis. J Forensic Leg Med. 2016;42:68-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Zhou W, Liu H, Qiu LZ, Yue LX, Zhang GJ, Deng HF, Ni YH, Gao Y. Cardiac efficacy and toxicity of aconitine: A new frontier for the ancient poison. Med Res Rev. 2021;41:1798-1811. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Cho YS, Choi HW, Chun BJ, Moon JM, Na JY. Quantitative analysis of aconitine in body fluids in a case of aconitine poisoning. Forensic Sci Med Pathol. 2020;16:330-334. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Jeon SY, Jeong W, Park JS, You Y, Ahn HJ, Kim S, Kim D, Park D, Chang H, Kim SW. Clinical relationship between blood concentration and clinical symptoms in aconitine intoxication. Am J Emerg Med. 2021;40:184-187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Wang XC, Jia QZ, Yu YL, Wang HD, Guo HC, Ma XD, Liu CT, Chen XY, Miao QF, Guan BC, Su SW, Wei HM, Wang C. Inhibition of the INa/K and the activation of peak INa contribute to the arrhythmogenic effects of aconitine and mesaconitine in guinea pigs. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2021;42:218-229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Sun GB, Sun H, Meng XB, Hu J, Zhang Q, Liu B, Wang M, Xu HB, Sun XB. Aconitine-induced Ca2+ overload causes arrhythmia and triggers apoptosis through p38 MAPK signaling pathway in rats. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2014;279:8-22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Li M, Xie X, Chen H, Xiong Q, Tong R, Peng C, Peng F. Aconitine induces cardiotoxicity through regulation of calcium signaling pathway in zebrafish embryos and in H9c2 cells. J Appl Toxicol. 2020;40:780-793. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |