Published online Nov 26, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i33.12380

Peer-review started: August 17, 2022

First decision: September 5, 2022

Revised: September 19, 2022

Accepted: October 26, 2022

Article in press: October 26, 2022

Published online: November 26, 2022

Processing time: 97 Days and 19.4 Hours

Primary malignant pericardial mesothelioma (PMPM) is an extremely rare malignant tumor, and it is difficult to diagnose definitively before death. We present a case in which PMPM was diagnosed at autopsy. We consider this case to be highly suggestive and report it here.

A 78-year-old male presented with transient loss of consciousness and falls. The transient loss of consciousness was considered to result from complications of diastolic dysfunction due to pericardial disease, fever with dehydration, and paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Ultrasound cardiography (UCG) and computed tomography showed cardiac enlargement and high-density pericardial effusion. We considered pericardial disease to be the main pathogenesis of this case. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging and gadolinium contrast-enhanced T1-weighted images showed thick staining inside and outside the pericardium. Pericardial biopsy was considered to establish a definitive diagnosis, but the patient and his family refused further treatment and examinations, and the patient was followed conservatively. We noticed a thickening of the pericardium and massive changes in the pericardium on UCG over time. We performed an autopsy 60 h after the patient died of pneumonia. Giemsa staining of the autopsy tissue showed an epithelial-like arrangement in the pericardial tumor, and immunostaining showed positive and negative factors for the diagnosis of PMPM. Based on these findings, the final diagnosis of PMPM was made.

PMPM has a poor prognosis, and early diagnosis and treatment are important. The temporal echocardiographic findings may provide a clue for the diagnosis of PMPM.

Core Tip: Primary malignant pericardial mesothelioma (PMPM) is an extremely rare malignant tumor that is difficult to diagnose definitively before death. We encountered a case of PMPM that could not be diagnosed before death. A 78-year-old male was admitted to our emergency department with the chief complaint of loss of consciousness. In his lifetime, PMPM had not been listed as a differential diagnosis based on several imaging examinations, but it was eventually diagnosed at autopsy. Imaging findings on ultrasound cardiography may aid in the antemortem diagnosis of PMPM, which is one of the differential diagnoses for pericardial disease.

- Citation: Oka N, Orita Y, Oshita C, Nakayama H, Teragawa H. Primary malignant pericardial mesothelioma with difficult antemortem diagnosis: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(33): 12380-12387

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i33/12380.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i33.12380

Primary malignant pericardial mesothelioma (PMPM) is an extremely rare malignant tumor[1]. PMPM-related symptoms are also nonspecific, and histological evaluation is necessary according to the current diagnostic criteria[2]. Diagnostic examinations other than autopsy include pericardiocentesis and pericardiotomy; however, such examinations cannot always be performed in all patients suspected of PMPM because of their invasiveness or poor conditions. Here, we present a case of PMPM in which the diagnosis was not made by several imaging examinations in the patient’s lifetime but was made by autopsy.

A 78-year-old male was admitted to our emergency department in September 2019 because of transient loss of consciousness and falls.

The patient reported a transient loss of consciousness and falls while walking in the morning after breakfast. He regained consciousness immediately.

The patient had been receiving treatment for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, diabetes mellitus, and chronic kidney disease at our hospital and at the family physician’s clinic. The patient was receiving direct oral anticoagulants and amiodarone for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation and dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitor and sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor for diabetes mellitus.

The patient had been smoking 20 cigarettes daily for 58 years, and his history of asbestos exposure was unknown.

The results of his physical examination were as follows: height, 1.58 m; weight, 51.6 kg; body mass index, 20.59 kg/m2; blood pressure, 91/53 mmHg; pulse rate, 92 beats/min and irregular; oxygen saturation in room air, 97%; body temperature, 37.9 °C; and respiratory rate, 16 breaths/min. At the time of the visit, the patient's level of consciousness was clear, and no obvious neurological abnormalities were observed. Mild anemia was observed in the ocular conjunctiva. Jugular venous distension was marked. On auscultation, the heart sounds were irregular but well audible, and there was no clear heart murmur or pericardial friction rub. In the lung field, normal breath sounds were present with no rales. There were no abnormal findings in the abdomen. Bilateral marked leg edema was noted.

The laboratory findings showed a high inflammatory response (white blood cell count, 17970/μL; C-reactive protein level, 16.58 mg/dL) and anemia (hemoglobin level, 9.8 g/dL). Renal function was reduced, and the brain natriuretic peptide level was slightly elevated at 370 pg/dL. Blood and urine cultures were negative for sepsis. A close examination for collagen disease was negative, as was a quantitative test for tuberculosis. Regarding tumor markers, the carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) level was slightly elevated (5.6 ng/dL), and the soluble interleukin-2 receptor level was elevated at 1760 U/mL.

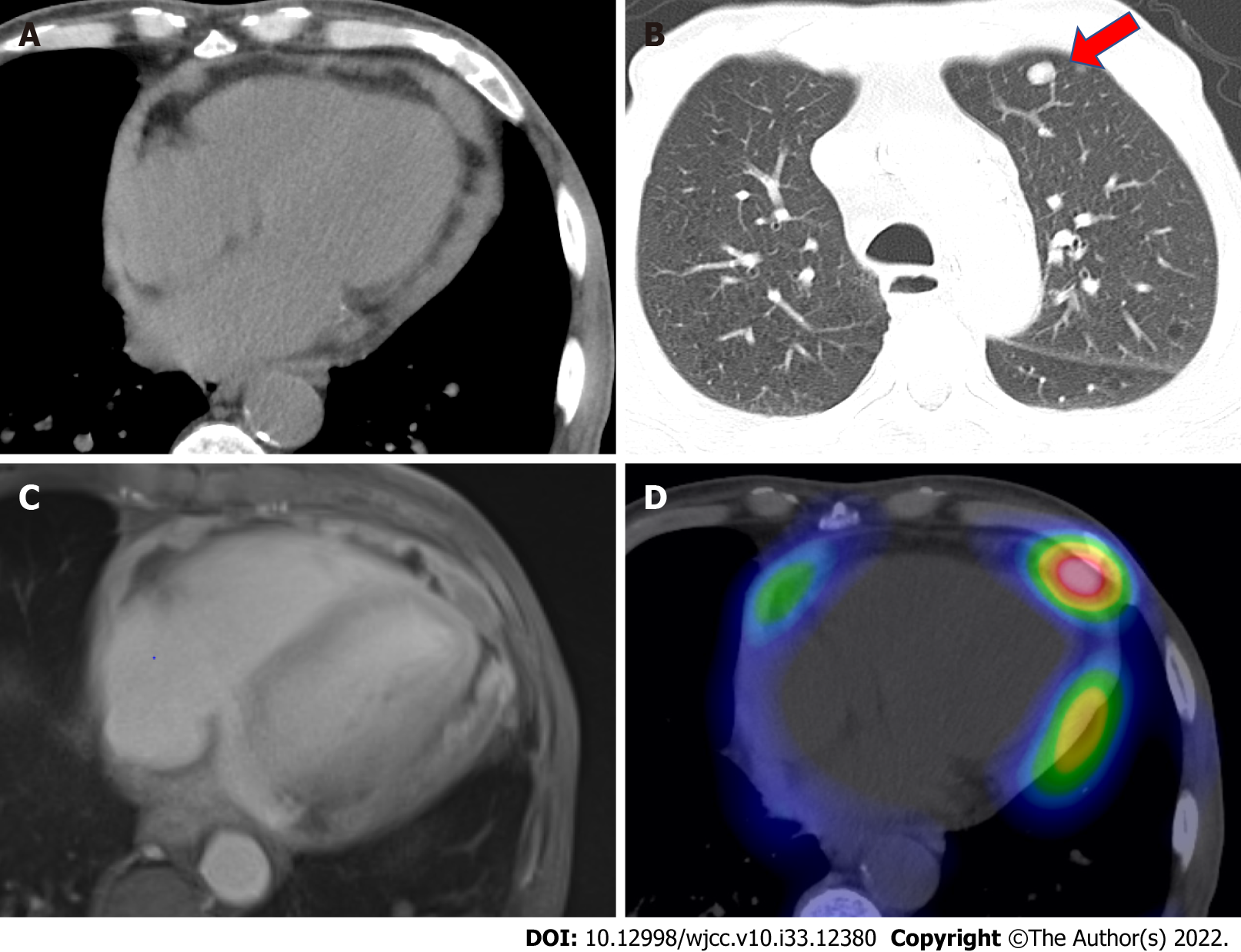

Electrocardiography showed the presence of atrial fibrillation. Chest radiography showed an increased cardiothoracic ratio of 68.7% and cardiac shadow enlargement, but no pleural effusion was noted. Plain computed tomography (CT) showed cardiac enlargement, a high density of pericardial effusion, and bilateral pleural effusion (Figure 1A). Circular nodular shadows (8 mm in diameter at the largest) were noted in the lungs (Figure 1B). Ultrasound cardiography (UCG) on admission also showed pericardial effusion with normal left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF). Regarding pericardial effusion, mild to moderate pericardial effusion was seen in all circumferential areas but seemed slightly more common in the posterior left ventricular (LV). There was no evidence of right ventricular or atrial collapse or septal bounce, which was not supportive of the presence of cardiac tamponade or constrictive pericarditis. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed faint high-signal areas in the pericardium on both T1- and T2-weighted images, and gadolinium contrast-enhanced T1-weighted images showed thick staining inside and outside the pericardium and a small amount of pericardial fluid (Figure 1C). The thickening of the pericardium was diffuse and did not present a clear tumor shadow. Gallium scintigraphy showed fluid accumulation in the pericardial cavity (Figure 1D).

The transient loss of consciousness may have been caused by diastolic dysfunction due to pericardial disease, dehydration due to fever and inflammation, and decreased cardiac output due to the appearance of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Regarding pericardial disease, which was considered the main pathology, in this case, we considered pericarditis or pericardial invasion or metastasis of the malignant disease. As shown above, CT showed nodular shadows in the lungs, and the possibility of malignancy could not be ruled out. Pericardial infiltration of this lung cancer was not actively suspected. Upper and lower gastrointestinal endoscopies were performed to exclude malignant disease, but no significant findings were observed. To confirm the final diagnosis, cardiac catheterization, thoracoscopic lung biopsy, chest CT-guided lung biopsy, and pericardial biopsy were recommended, while pericardiocentesis could not be performed because several images did not show pure pericardial effusion. We strongly recommended to the patient and his family that he undergo such examinations, but they refused further examinations and treatment, so these examinations were not performed.

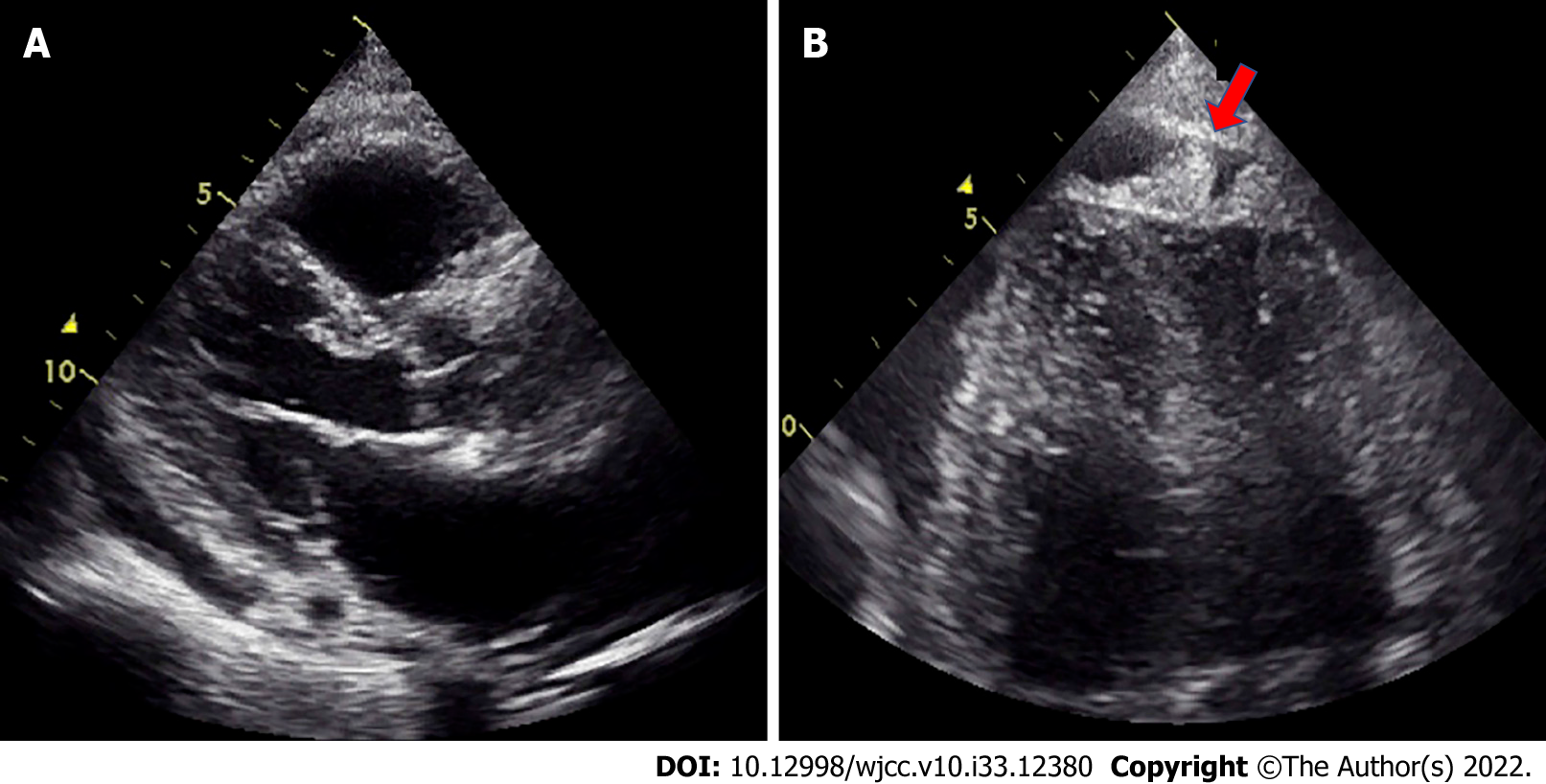

Furthermore, UCG on the 23rd day after admission showed that the LVEF was maintained within normal limits (66%). Pericardial effusions were slightly more observed near the posterior LV, but the degree of effusion was unchanged (Figure 2A). At this time, we found mass-like echogenicity at the apex, which was not present at the time of admission (Figure 2B). The E/A ratio was increased to 1.55, and the deceleration time was 140 ms on regular sinus rhythm, indicating progression of the restrictive disorder. On the 58th day after admission, because of an increase in pleural effusion, left thoracentesis was performed after obtaining consent; the effusion was exudative with no obvious atypical cells, suggesting some kind of inflammation.

Pericardial disease was the main pathology in this case, and although blood tests and as many imaging studies as possible were performed, a definitive diagnosis was not reached. A pericardial biopsy was recommended, but the patient did not wish to undergo aggressive examinations and/or treatment, and a definitive diagnosis was not reached before his death.

On admission, the patient’s loss of consciousness had improved, but because of possible complications of dehydration and inflammation, extracellular fluid replacement and antibiotics were administered, and the fever improved. On approximately the 20th day after admission, the patient again developed a fever with elevated inflammatory findings, and antibiotics were administered after culture tests were performed. From admission, rehabilitation had been performed, but after a fall on the 30th day after admission, rehabilitation had not progressed as expected. Around the 66th day, edema of both lower limbs became prominent, and the patient was treated with an increased dose of diuretics. In addition, he developed pneumonia and was treated with external fluid replacement, antibiotics, and intravenous dopamine infusion, but these measures were ineffective, and he died on his 77th day after admission.

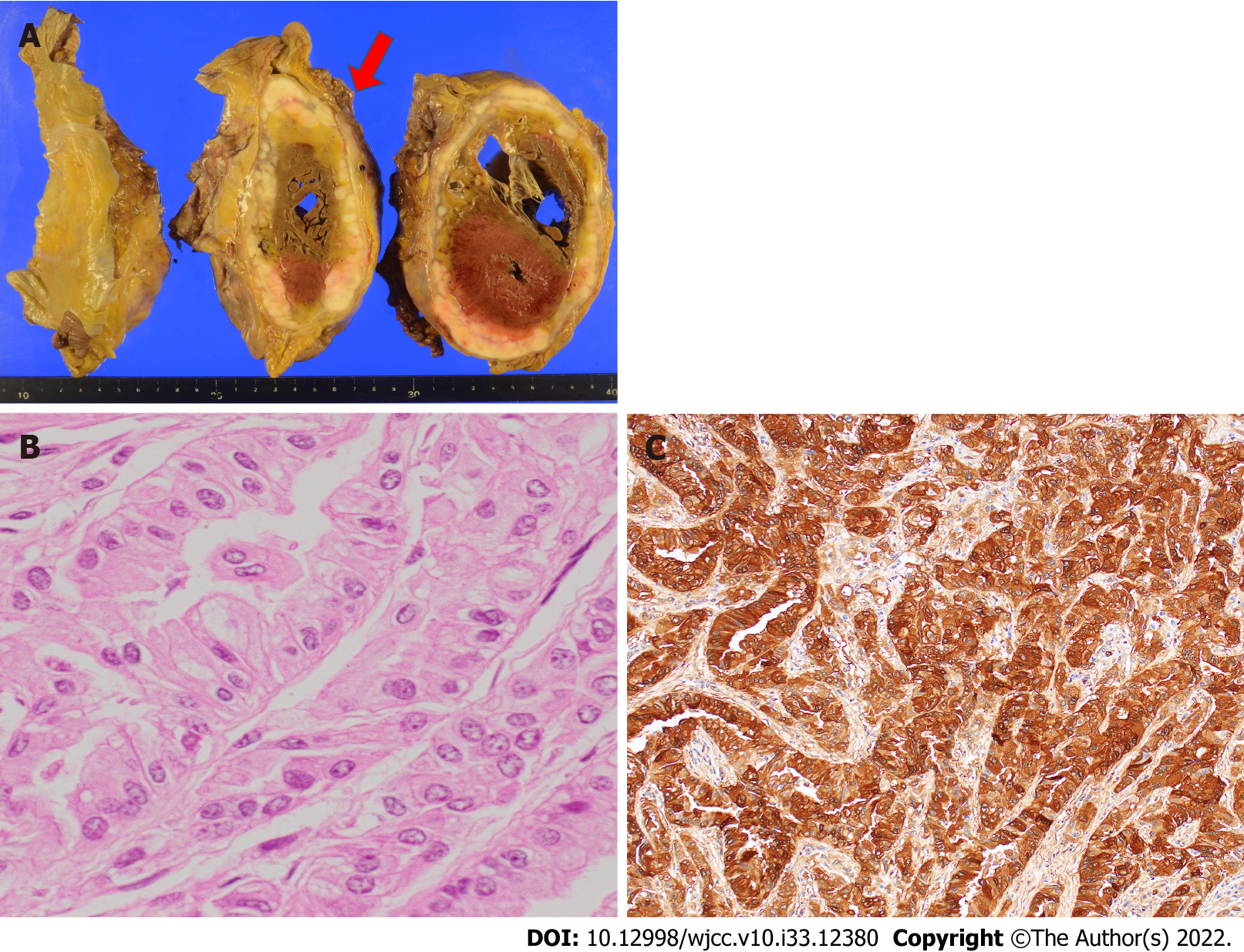

An autopsy, which was performed 60 h after death, showed a large tumor surrounding the pericardium and infiltration of the myocardium (Figure 3A). Giemsa staining showed an epithelial-like arrangement on the pericardial tumor (Figure 3B), and epithelial-type cells were also found in both lungs (subpleural). Immunostaining was positive for calretinin (Figure 3C) and podoplanin/D2-40 and negative for CEA, thyroid transcription factor-1 (TTF-1), napsin A, and claudin 4. Based on the autopsy findings, the final diagnosis of PMPM was made (Table 1).

| Antigen | Clone | Immunoreactivity |

| Calretinin | DAK Calret | + |

| Cytokeratin 5/6 | D5/16 B4 | + |

| WT-1 | 6F-H2 | - |

| Podoplanin | D2-40 | + |

| Claudin 4 | EPRR17575 | - |

| Epithelial related antigen | MOC-31 | - |

| CEA | II-7 | - |

| Epithelial antigen | BerEP-4 | - |

| TTF-1 | 8G7G3/1 | - |

| Napsin A | polyclonal | - |

| p40 | 11F12.1 | - |

| p63 | 4A4 | - |

| MTAP | 2G4 | - |

We reported a case of PMPM in which the final diagnosis was made based on autopsy. In the patient’s lifetime, PMPM had not been listed as a differential diagnosis based on several imaging examinations; meanwhile, we considered pericardial invasion or metastasis of other malignant disease.

PMPM is an extremely rare malignant tumor. In a large autopsy study, the prevalence was < 0.0022%[1,3]. Compared with pleural malignant mesothelioma, PMPM is less likely to be associated with asbestos exposure[4]. In the current case, the patient’s history of asbestos exposure was unknown. PMPM is difficult to diagnose and is often misdiagnosed. One reason is that it lacks the specificity of clinical symptoms, such as dyspnea and cough. These symptoms are common and are caused by many cardiac diseases, such as constrictive pericarditis, pericardial effusion, cardiac tamponade, and heart failure[1]. In this context, echocardiographic evaluation is the most commonly used diagnostic tool. In UCG, pericardial effusion (85.9%) was the most common finding, followed by pericardial mass (36.4%) and thickening (17.3%)[5]. In the present case, UCG on admission showed only pericardial effusion. However, UCG on the 23rd day showed not only pericardial effusion but also pericardial mass and pericardial thickening in the apex of the heart, accompanied by a restrictive pattern. These findings are suggestive of PMPM but are not always simultaneously present, and the successive performance of UCG may provide any hints for the diagnosis of PMPM.

Certainly, pathologic findings are needed for a definitive diagnosis. Andersen and Hansen set the criteria for PMPM in 1974, as follows: (1) The tumor is localized to the visceral side and wall of the epicardium; (2) When there is metastasis, it is localized only to the affiliated lymph nodes; (3) There are no other primary tumors; and (4) The autopsy has been completely performed[2]. Of the cases reported before 1985, 75% were postmortem diagnoses[6]. Regarding pathological evaluation in the patient’s lifetime, pericardial fluid cytology is sometimes difficult to diagnose, and pericardiocentesis can only diagnose 10%-30% of cases[3,4,7]. Even in the present case, pericardiocentesis was not performed because pericardial effusion did not mainly involve fluid, judging from several imaging examinations. Therefore, most definitive diagnoses are made by autopsy. In this case, a definitive diagnosis was made by autopsy, although our case met three of the four criteria (did not meet the second criterion) posited by Andersen and Hansen[2]. In our case, malignant mesothelioma was noted in the lung; however, considering the large tumor over the pericardium, these findings in the lungs were caused by lung metastasis.

Malignant mesothelioma is histologically classified into three types: epithelial type, sarcomatoid type, and biphasic type[8]. Epithelial types are the most frequent types, biphasic types are the least frequent[3], and the tumor classification in the present patient was epithelial. Immunostaining is essential for the pathological diagnosis of mesothelioma. When epithelial or biphasic mesothelioma is suspected, positive markers include calretinin, Wilms tumor-1 (WT-1), and podoplanin/D2-40, and negative markers include CEA, TTF-1, napsin A, and claudin 4[9]. Since there are no markers with 100% sensitivity and specificity, it is recommended that at least two positive markers and at least two negative markers be used as the basis for the diagnosis of epithelial mesothelioma[9]. In this case, calretinin and podoplanin/D2-40 were positive as positive markers, and CEA, TTF-1, napsin A, and claudin 4 were negative as negative markers, which was one of the reasons for the diagnosis. In the present case, WT-1, a positive marker, was negative. An autopsy of this case was performed 60 h postmortem, and this time course may have affected the immunostaining results (Table 1).

PMPM is difficult to diagnose and highly malignant, so the stage is often advanced when it is diagnosed. The prognosis for life is poor, and even if treated, the prognosis is within 10 mo[10]. Lymph node metastasis is found in 30%-50% of cases, and the prognosis is extremely poor with lymph node metastasis[3,7,11]. There is no effective or standard treatment for this disease. Localized lesions are the only lesions that can be surgically resected for curative purposes, but diffuse lesions are difficult to access[12]. Although there may have been no effective treatment even if an antemortem diagnosis had been made in this case, chemotherapy and radiotherapy have been effective[1,4,11,13,14], and it was necessary to list this case in the differential diagnosis based on the UCG findings.

Looking back on the examinations and progress of the present case, there were several points for improvement, which are listed here. First, in this case, a close examination of the gastrointestinal tract was performed to rule out malignant disease of the gastrointestinal tract. Nevertheless, this examination alone was not sufficient and may have placed an additional burden on the patient. Second, in the present study, we performed gallium scintigraphy; however, 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG PET) has been established as the standard examination for malignancies, and it seems superior to gallium scintigraphy in identifying inflammation[15]. Nevertheless, we do not have FDG PET equipment at our hospital. It is difficult under the Japanese insurance system for hospitalized patients to have FDG PET performed at other facilities. Thus, in the present case, 18F-FDG PET was not performed, which could have provided more clinical information. Third, other than T1W, T2W, and gadolinium-enhanced T1W images, many MRI sequences and findings are valuable in the diagnosis of cardiac/pericardial masses, such as perfusion images (to see tumor vascularity), T1W with fat suppression images (to exclude pericardial lipoma), and advanced images if available (native T1 mapping, T2 mapping, extracellular volume mapping, etc.). Although the specific imaging and/or analyses might have helped in differentiation, we did not perform the MRI examination after listing sufficient differential diseases and providing imaging conditions. In addition, some analyses cannot be performed with our MRI equipment. Finally, a pericardial biopsy was still preferred for a definitive diagnosis. We were not able to perform the biopsy because the patient and family did not wish to do so, but we could have made more effort to explain the procedure to them.

In conclusion, we encountered a case of PMPM, which was difficult to diagnose definitively during the patient’s lifetime based on several imaging examinations. For early diagnosis or diagnosis in the patient’s lifetime, the combination of the presence of pericardial effusion, mass, and thickening on successive UCG may suggest the presence of PMPM, which should be one of the differential diagnoses for pericardial disease, irrespective of the absence of asbestos exposure.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: Japan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Theerasuwipakorn N, Thailand; Yang L, China S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: A P-Editor: Gao CC

| 1. | Suman S, Schofield P, Large S. Primary pericardial mesothelioma presenting as pericardial constriction: a case report. Heart. 2004;90:e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Andersen JA, Hansen BF. Primary pericardial mesothelioma. Dan Med Bull. 1974;21:195-200. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Nilsson A, Rasmuson T. Primary Pericardial Mesothelioma: Report of a Patient and Literature Review. Case Rep Oncol. 2009;2:125-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Thomason R, Schlegel W, Lucca M, Cummings S, Lee S. Primary malignant mesothelioma of the pericardium. Case report and literature review. Tex Heart Inst J. 1994;21:170-174. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Kong L, Li Z, Wang J, Lv X. Echocardiographic characteristics of primary malignant pericardial mesothelioma and outcomes analysis: a retrospective study. Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2018;16:7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Nambiar CA, Tareif HE, Kishore KU, Ravindran J, Banerjee AK. Primary pericardial mesothelioma: one-year event-free survival. Am Heart J. 1992;124:802-803. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | McGehee E, Gerber DE, Reisch J, Dowell JE. Treatment and Outcomes of Primary Pericardial Mesothelioma: A Contemporary Review of 103 Published Cases. Clin Lung Cancer. 2019;20:e152-e157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Galateau-Salle F, Churg A, Roggli V, Travis WD; World Health Organization Committee for Tumors of the Pleura. The 2015 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Pleura: Advances since the 2004 Classification. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11:142-154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 202] [Cited by in RCA: 195] [Article Influence: 21.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Husain AN, Colby TV, Ordóñez NG, Allen TC, Attanoos RL, Beasley MB, Butnor KJ, Chirieac LR, Churg AM, Dacic S, Galateau-Sallé F, Gibbs A, Gown AM, Krausz T, Litzky LA, Marchevsky A, Nicholson AG, Roggli VL, Sharma AK, Travis WD, Walts AE, Wick MR. Guidelines for Pathologic Diagnosis of Malignant Mesothelioma 2017 Update of the Consensus Statement From the International Mesothelioma Interest Group. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2018;142:89-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 328] [Cited by in RCA: 401] [Article Influence: 50.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ost P, Rottey S, Smeets P, Boterberg T, Stragier B, Goethals I. F-18 fluorodeoxyglucose PET/CT scanning in the diagnostic work-up of a primary pericardial mesothelioma: a case report. J Thorac Imaging. 2008;23:35-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Watanabe A, Sakata J, Kawamura H, Yamada O, Matsuyama T. Primary pericardial mesothelioma presenting as constrictive pericarditis: a case report. Jpn Circ J. 2000;64:385-388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Fujita K, Hata M, Sezai A, Minami K. Three-year survival after surgery for primary malignant pericardial mesothelioma: report of a case. Surg Today. 2014;44:948-951. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Chung SM, Choi SJ, Kim MJ, Choi JY, Kim HJ, Lee SY, Kang EJ. Positive response of a primary malignant pericardial mesothelioma to pemetrexed plus cisplatin followed by pemetrexed maintenance chemotherapy: A case report. Oncol Lett. 2016;12:213-216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Vogelzang NJ, Rusthoven JJ, Symanowski J, Denham C, Kaukel E, Ruffie P, Gatzemeier U, Boyer M, Emri S, Manegold C, Niyikiza C, Paoletti P. Phase III study of pemetrexed in combination with cisplatin vs cisplatin alone in patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2636-2644. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2425] [Cited by in RCA: 2271] [Article Influence: 103.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kubota K, Tanaka N, Miyata Y, Ohtsu H, Nakahara T, Sakamoto S, Kudo T, Nishiyama Y, Tateishi U, Murakami K, Nakamoto Y, Taki Y, Kaneta T, Kawabe J, Nagamachi S, Kawano T, Hatazawa J, Mizutani Y, Baba S, Kirii K, Yokoyama K, Okamura T, Kameyama M, Minamimoto R, Kunimatsu J, Kato O, Yamashita H, Kaneko H, Kutsuna S, Ohmagari N, Hagiwara A, Kikuchi Y, Kobayakawa M. Comparison of 18F-FDG PET/CT and 67Ga-SPECT for the diagnosis of fever of unknown origin: a multicenter prospective study in Japan. Ann Nucl Med. 2021;35:31-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |