Published online Nov 26, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i33.12358

Peer-review started: August 8, 2022

First decision: September 5, 2022

Revised: September 10, 2022

Accepted: October 11, 2022

Article in press: October 11, 2022

Published online: November 26, 2022

Processing time: 106 Days and 16.8 Hours

Intercalated duct lesions (IDLs) are considered relatively benign and rare tumors of salivary glands, that were only described recently. Their histopathological appearance may range from ductal hyperplasia to encapsulated adenoma with hybrid patterns of both variants. It is thought that IDLs may be the precursor for malignant proliferations, therefore their correct diagnosis remains crucial for proper lesion management. It is the first reported IDL case arising from the accessory parotid gland (APG), which stands for less frequent but higher mal

A 24-years-old male with no accompanying diseases was referred to the hospital with a painless nodule on the right cheek. On physical examination, the stiff, immobile, and painless mass was palpable in the anterior portion of the right parotideomasseteric region, just superior to the parotid duct. Ultrasound exam

Fine needle aspiration biopsy might not always be diagnostic, and given the malignant potential, the surgical resection of such lesion remains the treatment of choice.

Core Tip: In this article we present a clinical case of a patient diagnosed with a hybrid intercalated duct lesion (IDL) tumor of the accessory parotid gland. It is the first reported IDL case arising from such location, which stands for less frequent but higher malignancy rate tumor developmental area. We also discuss potential diagnostic pitfalls associated with unusual growth site, describe the further treatment choice, and review the available literature.

- Citation: Stankevicius D, Petroska D, Zaleckas L, Kutanovaite O. Hybrid intercalated duct lesion of the parotid: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(33): 12358-12364

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i33/12358.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i33.12358

Intercalated duct lesions (IDLs) are considered relatively benign and rare tumors of salivary glands, that were only described recently. According to the largest IDL study to date, in most cases they present as asymptomatic, up to a centimeter in diameter parotid gland nodules with a female to male ratio of 1.7:1[1]. IDL histopathological appearance may range from intercalated duct hyperplasia (IDH) to encapsulated intercalated duct adenoma (IDA) with hybrid patterns[1]. The pathogenesis of IDL is still not well established, nonetheless the links to chronic sialadenitis, sialolithiasis, gland atrophy and radiation therapy are documented[2]. It is suggested that IDLs may be the precursor lesion for neoplastic proliferations such as basal cell adenoma (BCA) or even epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma (EMC) when present in the parotid gland[3,4]. However, due to a low incidence, the data regarding such lesions remains limited and the disorder is not widely recognized by clinicians and pathologists.

We report a clinical case of a 24-years-old male patient with a tumor of hybrid pattern IDL originating from the accessory parotid gland (APG). To our knowledge, it is the first report of the IDL arising in a such location. Moreover, here we discuss potential diagnostic pitfalls associated with unusual growth area and further treatment choice.

A 24-years-old smoker male with no accompanying diseases was referred to The National Cancer Institute with a painless nodule on the right cheek, which he stated as having been present for 6 mo.

The palpable mass was present for 6 mo with no evidence of growth.

No previous history of head and neck trauma, sialadenitis, sialolithiasis, oncological disease, or radiotherapy was noted.

The patient was a smoker with no accompanying diseases. Family history was unremarkable.

On physical examination, the mass was palpable in the anterior portion of the right parotideomasseteric region, just superior to the parotid duct. The nodule was stiff, immobile, and painless on palpation. The skin above it remained unaffected.

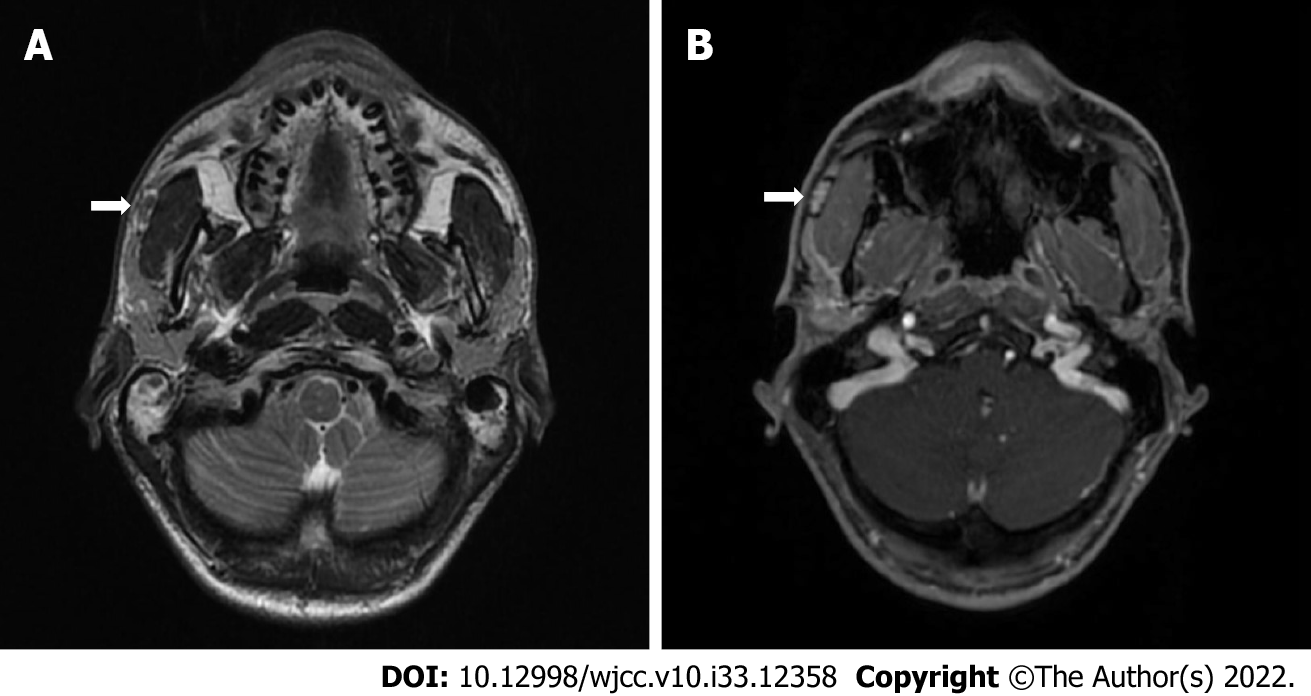

Ultrasound examination demonstrated 1.5 cm × 1.0 cm hypoechogenic mass on the anterior part of the right parotid gland, laying on the surface of masseter muscle with no signs of inflammation, and slightly enlarged submandibular lymph nodes. Ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration cytology, followed by liquid-based fine needle aspiration biopsy were performed. However, the results came out uninformative. A contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the parotid was obtained. T2-weighted image demonstrating a well encapsulated 1.5 cm × 1.0 cm × 0.5 cm tumor with high-intensity signal capsule together with low-intensity signal core in the very anterior part of the parotideomasseteric region (Figure 1A). A contrast-enhanced T1-weighted image showed a contrast accumulating core and no clear contrast accumulation in the capsule (Figure 1B). MRI, performed for other reasons 4 years prior to the present disease onset, did not show any evidence of tumor presence. The well-defined margined and encapsulated mass prompted of benign pleomorphic adenoma, however hyperintense capsule and submandibular lymphadenopathy were uncharacteristic features, therefore surgical resection followed up.

Tumor of the right APG, which after surgical resection and histopathological examination was confirmed as hybrid form of IDL.

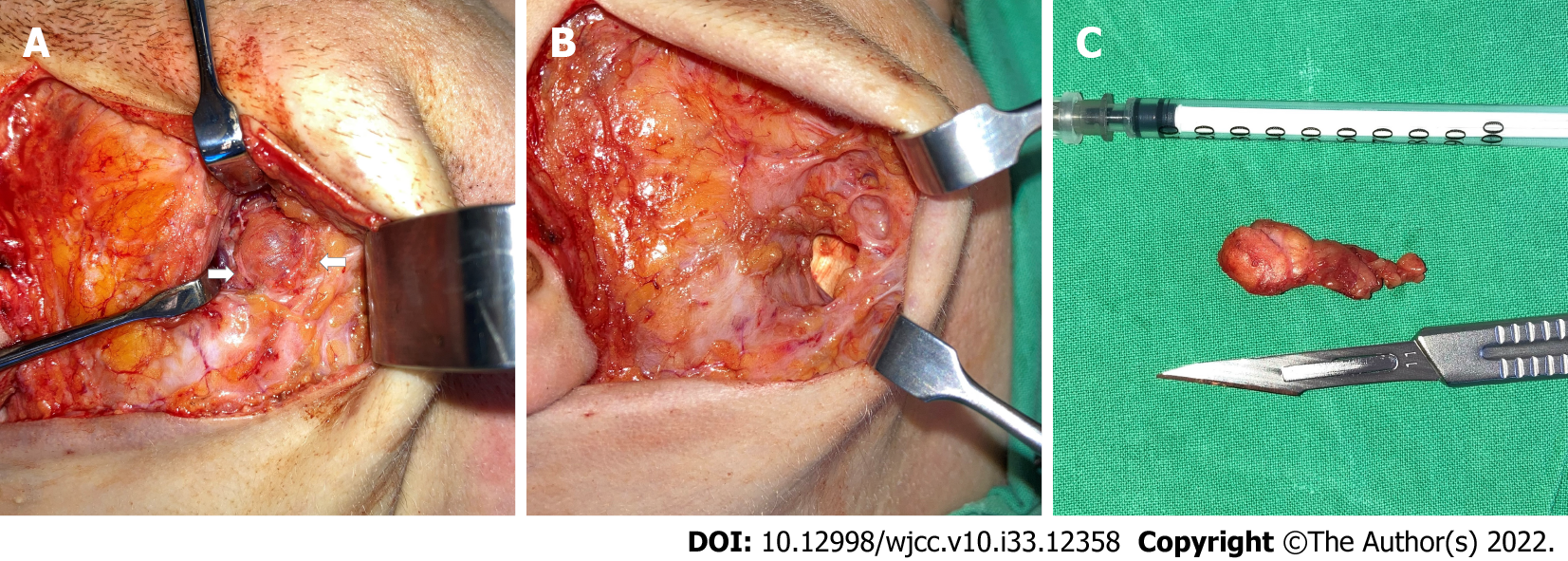

Right facelift skin incision was performed, and the skin flap was raised through the subcutaneous dissection then separated from the superficial musculoaponeurotic system reaching the anterior portion of the parotid gland. The great auricular nerve was identified and preserved. The anterior border of the parotid gland was reached using Colorado microdissection needle (Stryker Craniomaxillofacial). The tumor was identified between two buccal facial nerve branches (Figure 2A) originating at the very anterior portion of the parotideomasseteric region, separately from the main parotid gland. The mass was found lying above the masseter muscle superior to the Stensen duct, suggesting that the tumor’s origin was the APG. Using surgical loupes, extracapsular dissection of the tumor was performed, sparing both buccal branches of the facial nerve. The surgical resection cavity was visible over imprinted masseter muscle fibers (Figure 2B). The Penrose drain was placed, and the wound was closed in a two-layer manniere. Further, the pathological specimen was sent to the National Center of Pathology for histopathological evaluation (Figure 2C). No signs of facial nerve palsy or weakness were visible postoperatively. The patient was discharged home on the 3rd postoperative day after full control of pain and edema. Sutures were removed 7th day postoperatively.

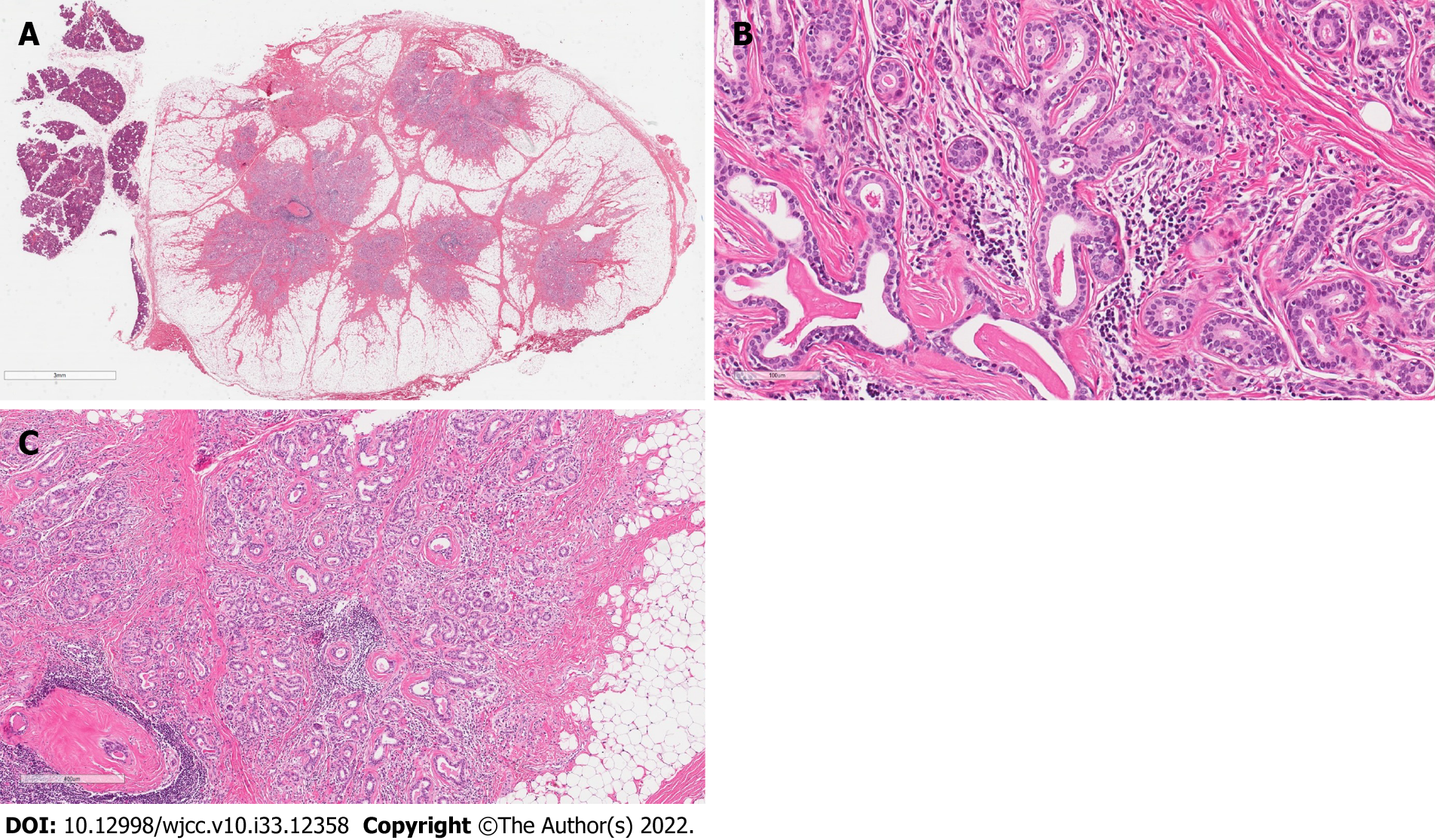

On gross examination, the specimen revealed a circumscribed fatty appearance. Microscopically in slides made from the formalin fixed paraffin embedded tissue cut and stained with hematoxylin/eosin, the lesion was a 15 mm × 10 mm nodule of regular border composed by a partially encapsulating thin layer of fibrous tissue. In longitudinal sections, the lesion was composed of numerous small tubules surrounded by a large amount of adipose tissue (Figure 3A). The epithelial component contained no acinar cells and lacked evidence of infiltrative growth. The tubules were surrounded by a collagenous membrane and consisted of two cell layers: Cuboidal ductal cells (with small round, cytologically bland nuclei and with pale amphophilic cytoplasm) and myoepithelial cells with elongated nuclei (Figure 3B). There was evidence of fibrosis, periductal hyalinization and focal periductal chronic inflammation within the tumor (Figure 3C). No accumulations of amyloid (by staining with Kongo Red method) or fungi (by staining with periodic acid shift method) were found.

All microscopic criteria support a conclusion of the salivary gland IDL with hybrid features due to a partially round, thinly encapsulated adenoma-like appearance and irregular hyperplasia-like areas of benign tubules with abundant intervening stroma.

The patient was requested for follow-up visit after 6 mo and 1 year post surgery. No recurrence or metastasis of the disease were found, and the surgical scar was fully healed and barely visible.

IDLs are rare salivary gland tumors that are usually detected in major salivary glands with a dominant location of the parotid gland. However, the incidence rate of IDL is low, therefore the data regarding such lesions remains limited: Only case reports and case series were published up to this date, since the first printed case in 1994[5]. While healthy salivary gland epithelial tissue consists of acinar cells and ductal components that are divided into excretory, striated, and intercalated, the IDL in turn is the abnormal proliferation of intercalated ducts. The architectural appearance of IDL may range from IDH to IDA or hybrid patterns of both variants[1]. Histologically IDH is characterized as the unencapsulated proliferation of intercalated ducts that interpose into the surrounding salivary gland parenchyma. In contrast, IDA has well defined fibrous capsule that separates them from the healthy salivary gland tissue. The hybrid pattern, as the name suggests, has both IDH and IDA structural properties, containing irregular and thinly encapsulated margins and intervening stroma. According to the study, conducted by Weinreb et al[1], the hybrid pattern stands for the least common finding (4 cases) followed by IDA (9 cases) and IDH (15 cases).

It is important to emphasize the malignancy potential of such lesions and their association with other salivary gland tumors. In the research of Montalli et al[4] the tubular variant of BCA showed IDL-like areas with closely apposed ducts. In both, the immunoprofile of luminal and myoepithelial cells were reminiscent of intercalated ducts, with the only difference of greater quantity of myoepithelial cells in BCA. Therefore, they stated that IDLs are closely related to tubular BCA and at least some BCAs can arise from IDLs. In the already mentioned study of Weinreb et al[1], the most obvious connection of IDL was seen with EMC and BCA. They concluded that IDL might be a precursor lesion of these neoplasms. However, all of EMC and BCA cases seemed to be arising from IDH and hybrid forms of IDL, while IDA alone did not provoke above mentioned malignancies. Such relation, specifically of hyperplasia of intercalated ducts, was noticed in a few other papers. Chetty[3] found IDH zones in 3 of 7 EMC cases. Since the proliferating intercalated ducts were in close proximity to EMC and to the case containing mucoepidermoid carcinoma, the author stated that IDH may be a precursor lesion for both EMC and “hybrid” carcinomas. In a paper by Di Palma[5], the transition of IDH to EMC was captured. The overgrowth of myoepithelial cells which infiltrated the surrounding stroma in the area where proliferating intercalated ducts merged with surrounding acini was noticed. In the case presented here, the thinly encapsulated and well-defined primary hybrid IDL tumor did not show any signs of potential malignant transformations on a histopathological basis. However, the possible neoplastic links between IDLs and other neoplasms remain poorly explored and demand further investigation.

The results of IDL immunohistochemical and genetic analyses were discussed in the recently published paper by Kusafuka et al[6]. They support the theory that IDL is the “sprout” lesion of BCA or basal cell adenocarcinoma rather than EMC due to its immunohistochemical profile and missense mutation in the CTNNB1 gene. Even though no specific marker for intercalated ducts has yet been found, some authors consider intercalated duct-related molecules. SRY-Box Transcription Factor 10 (SOX10) molecule expression was positive in acinic cell carcinoma, adenoid cystic carcinoma, EMC and myoepithelioma, therefore their intercalated duct origins were suggested[7]. Chênevert et al[8] surveyed the expression of anoctamin-1 (DOG1) in human salivary tissues and tumors. The DOG1 was found positive in IDA and IDH as a precursor lesion for secretory adenoma, EMC, and cystadenoma.

The data regarding the epidemiology of this lesion is scarce, most likely due to its’ low incidence and usually small, undetectable tumor size. According to the largest study to date, describing a total of 32 IDL cases, the female to male sex ratio was 1.7:1 (19 women, 11 men, 2 unknown) and the mean age during diagnosis was 53.8 years[1]. We have found two other similar papers that report IDL cases originating from the parotid gland as hyperplastic and hybrid forms[9,10]. Mok et al[9] reported a hybrid form of parotid gland IDL where such lesion for the first time was detected by fine needle aspiration biopsy. They also forewarn potential differential diagnostic pitfalls associated with varied architectural features proposing its’ special awareness during microscopic evaluation. In our case, however, the fine needle aspiration biopsy findings were uninformative, thus the final diagnosis was confirmed after excision and histopathological analysis. Another paper presented an IDH case, that was similarly diagnosed after superficial parotidectomy before non-diagnostic results of the biopsy[10]. Taking into account that biopsy results can be rarely informative, we believe, surgical consideration is decisive, since there is a likelihood of potential malignization and the correct diagnosis is crucial for proper lesion management.

The developmental location of IDL is usually in the parotid gland (82%) with only a few described exceptions in the submandibular gland (12%) and oral cavity (6%)[1]. In this report we present a case of IDL of hybrid type originated from the APG. Based on the literature, APG anatomical variation stands for 21%–56% of the population[11,12]. Moreover, tumors originating from accessories are even less common – only 1%–7.7% of all parotid gland tumors[13,14]. On the other hand, they stand for higher malignancy rate tumors, ranging from 26% to 50%, compared to main parotid gland neoplasms[13,15]. The recently appeared article states that out of 792 parotid gland tumors, only 13 (1.64%) arise from APG[16]. Pleomorphic adenoma was the most common histological subtype (53.8%), followed by benign myoepithelioma (7.5%), malignant mucoepidermoid carcinoma (23.1%), carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma (7.5%) and adenoid cystic carcinoma (7.5%). Early studies have noticed the impact of chronic sialadenitis, sialolithiasis, gland atrophy and radiation therapy on the development of such lesions[2]. Interestingly, our patient was not associated with any of these factors. It should be noted that no evidence of tumor presence was visible in the MRI scan, performed 4 years prior to lesion onset. Therefore, we presume that IDL might be a relatively fast-growing tumor. According to another report, the nodule was palpable for only 1 mo until administration to the hospital[10]. This feature should draw special clinician attention as it may warn a malignant process. To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of IDL originating from APG. We also believe such location causes differential diagnostic challenges and should include neoplasms in the mid-cheek region. This caution is supported by Koudounarakis et al[17] case where APG tumor was misdiagnosed as glomus tumor.

We presented a case of a hybrid form of IDL, originating from the APG. In this location the development of tumors is less frequent, but they pose a higher malignancy rate. Fine needle aspiration biopsy results might not always be diagnostic, and given the malignant potential, the surgical resection of such lesions remains the treatment of choice.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: Lithuania

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D, D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Gokce E, Turkey; Xu HT, China S-Editor: Liu XF L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu XF

| 1. | Weinreb I, Seethala RR, Hunt JL, Chetty R, Dardick I, Perez-Ordoñez B. Intercalated duct lesions of salivary gland: A morphologic spectrum from hyperplasia to adenoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:1322-1329. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Yu GY, Donath K. Adenomatous ductal proliferation of the salivary gland. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2001;91:215-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Chetty R. Intercalated duct hyperplasia: possible relationship to epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma and hybrid tumours of salivary gland. Histopathology. 2000;37:260-263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Montalli VA, Martinez E, Tincani A, Martins A, Abreu Mdo C, Neves C, Costa AF, Araújo VC, Altemani A. Tubular variant of basal cell adenoma shares immunophenotypical features with normal intercalated ducts and is closely related to intercalated duct lesions of salivary gland. Histopathology. 2014;64:880-889. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Di Palma S. Epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma with co-existing multifocal intercalated duct hyperplasia of the parotid gland. Histopathology. 1994;25:494-496. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kusafuka K, Baba S, Kitani Y, Hirata K, Murakami A, Muramatsu A, Arai K, Suzuki M. A symptomatic intercalated duct lesion of the parotid gland: A case report with immunohistochemical and genetic analyses. Med Mol Morphol. 2022;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ohtomo R, Mori T, Shibata S, Tsuta K, Maeshima AM, Akazawa C, Watabe Y, Honda K, Yamada T, Yoshimoto S, Asai M, Okano H, Kanai Y, Tsuda H. SOX10 is a novel marker of acinus and intercalated duct differentiation in salivary gland tumors: A clue to the histogenesis for tumor diagnosis. Mod Pathol. 2013;26:1041-1050. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Chênevert J, Duvvuri U, Chiosea S, Dacic S, Cieply K, Kim J, Shiwarski D, Seethala RR. DOG1: A novel marker of salivary acinar and intercalated duct differentiation. Mod Pathol. 2012;25:919-929. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 173] [Cited by in RCA: 163] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Mok Y, Pang YH, Teh M, Petersson F. Hybrid intercalated duct lesion of the parotid: Diagnostic challenges of a recently described entity with fine needle aspiration findings. Head Neck Pathol. 2016;10:269-274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Naunheim MR, Lin HW, Faquin WC, Lin DT. Intercalated duct lesion of the parotid. Head Neck Pathol. 2012;6:373-376. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Frommer J. The human accessory parotid gland: Its incidence, nature, and significance. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1977;43:671-676. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Toh H, Kodama J, Fukuda J, Rittman B, Mackenzie I. Incidence and histology of human accessory parotid glands. Anat Rec. 1993;236:586-590. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Johnson FE, Spiro RH. Tumors arising in accessory parotid tissue. Am J Surg. 1979;138:576-578. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Perzik SL, White IL. Surgical management of preauricular tumors of the accessory parotid apparatus. Am J Surg. 1966;112:498-503. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Guzzo M, Locati LD, Prott FJ, Gatta G, McGurk M, Licitra L. Major and minor salivary gland tumors. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2010;74:134-148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 255] [Cited by in RCA: 308] [Article Influence: 19.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Luksic I, Mamic M, Suton P. Management of accessory parotid gland tumours: 32-year experience from a single institution and review of the literature. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2019;48:1145-1152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Koudounarakis E, Karatzanis A, Nikolaou V, Velegrakis G. Pleomorphic adenoma of the accessory parotid gland misdiagnosed as glomus tumour. JRSM Short Rep. 2013;4:23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |