Published online Nov 26, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i33.12136

Peer-review started: July 6, 2022

First decision: September 25, 2022

Revised: September 30, 2022

Accepted: October 26, 2022

Article in press: October 26, 2022

Published online: November 26, 2022

Processing time: 140 Days and 4.8 Hours

Tubal endometriosis (TEM) is a category of pelvic endometriosis (EM) that is characterized by ectopic endometrial glands and/or stroma within any part of the fallopian tube. The fallopian tubes may be a partial source of ovarian endometriosis (OEM). TEM is difficult to diagnose during surgery and is usually detected by pathology after surgery.

To provide a clinical basis for the diagnosis and treatment of TEM.

In this study, the data of 30 patients who underwent laparoscopic salpingectomy due to various gynecological diseases and had pathological confirmation of TEM at our hospital were retrospectively analyzed, and the clinical basis for the diagnosis and treatment of TEM was evaluated.

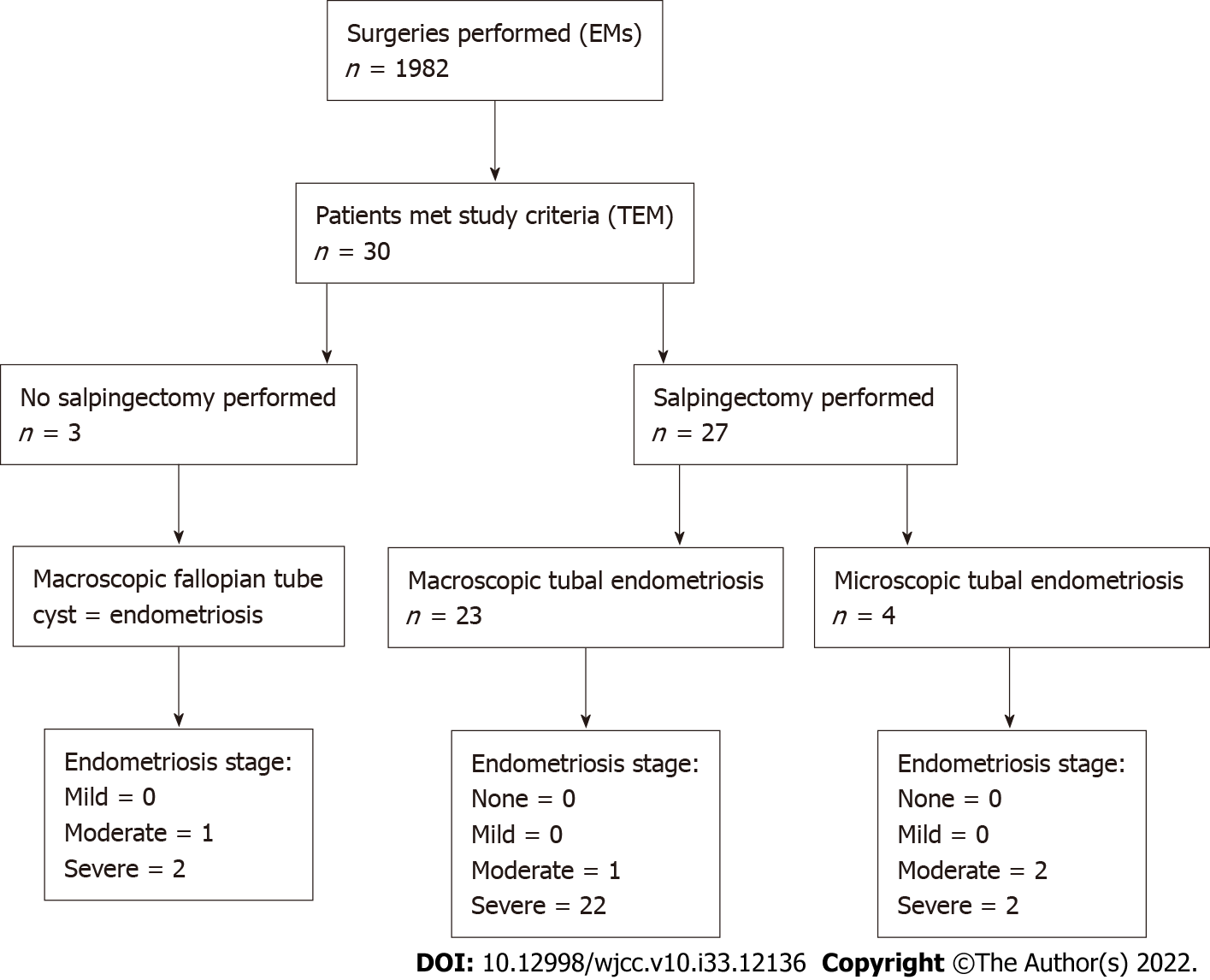

Among 1982 surgical patients, 30 met the study criteria. Among those, 6 patients had a history of infertility, 12 patients had a history of artificial abortion, 13 patients had a history of cesarean section, 1 patient had a history of tubal ligation, 4 patients had an intrauterine device, and 22 patients had hydrosalpinx. Sixteen patients (53.33%) conceived naturally and gave birth to healthy babies. Pathology showed that only 2 patients had TEM without any other gynecological diseases, while the others all had simultaneous diseases, including 26 patients with EM at other pelvic sites.

The final diagnosis of TEM depends on pathological examination since there are no specific clinical characteristics. The rate of TEM combined with EM (especially OEM) was higher than that of other gynecological diseases, which indicates that TEM is related to OEM.

Core Tip: Tubal endometriosis (TEM) is a category of pelvic endometriosis that is characterized by ectopic endometrial glands and/or stroma within any part of the fallopian tube. The fallopian tubes may be a partial source of ovarian endometriosis (OEM). In this study, 30 patients who underwent laparoscopic salpingectomy due to various gynecological diseases and were pathologically confirmed as having TEM at our hospital were retrospectively analyzed to provide a clinical basis for the diagnosis and treatment of TEM. The final diagnosis of TEM depends on pathological examination since there are no specific clinical characteristics. The rate of TEM combined with OEM was higher than that of other gynecological diseases, which indicates that TEM is related to OEM.

- Citation: Jiao HN, Song W, Feng WW, Liu H. Diagnosis and treatment of tubal endometriosis in women undergoing laparoscopy: A case series from a single hospital. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(33): 12136-12145

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i33/12136.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i33.12136

Endometriosis (EM) is a common, estrogen-driven chronic condition in which endometrium-like epithelial and stromal cells are implanted at ectopic sites beyond their native location, namely, the internal lining of the uterine cavity[1]. Tubal endometriosis (TEM) is a type of pelvic EM that is characterized by ectopic endometrial glands and/or stroma on any part of the fallopian tube. The causes of tubal dysfunction in EM may be hydrosalpinx, tubal blockage or adhesion formation. Up to 30% of women with EM have some form of tubal involvement[2]. Studies have suggested that the fallopian tubes may be a partial source of ovarian endometriosis (OEM)[3,4]. TEM is difficult to diagnose during surgery and is usually detected by pathology after surgery. In our study, the clinical and pathological characteristics of TEM were analyzed, and the correlation between TEM and OEM was analyzed to provide a clinical basis for the diagnosis and treatment of TEM.

Among 1982 patients diagnosed with EM at Ruijin Hospital affiliated with Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, 30 patients were diagnosed with pathologically confirmed TEM and underwent laparoscopy due to various gynecological diseases from January 2013 to December 2021. The clinical data and pathological features of the patients, including age, fertility and contraceptive status, clinical manifestations, concomitancy of other gynecological diseases, and surgical methods, were collected.

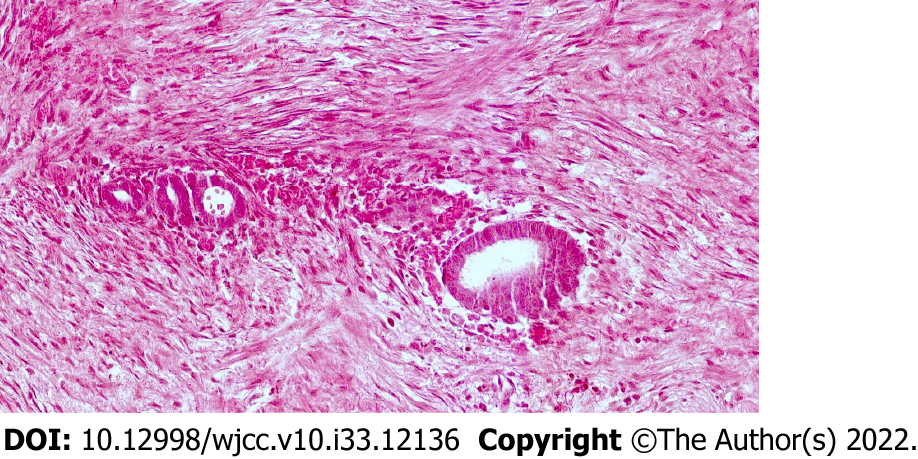

TEM was defined as the presence of ectopic endometrial glands and/or stroma in the fallopian tube, and 30 patients met this criterion.

In our study, we used immunohistochemistry to diagnose EM. Regarding the anatomical distribution of TEM, lesions of the proximal tube have been shown to mainly affect the mucosa, whilst lesions of the distal tube tend to affect the serosa/subserosa. Some authors have proposed that only lesions beyond the isthmus should be considered as TEM, whilst those proximal to the isthmus could be defined as endometrial colonisation Thus, the limited evidence suggests lesions may be more prevalent beyond the isthmus and ampulla[1].We will give consideration to potential lesions in the medial portion of the fallopian tube since TEM at this part could be confused with endometrial epithelization of the fallopian tube, and further research will be carried out in the future.

Normally distributed data are expressed as the means ± SD, while nonnormally distributed data are expressed as medians (ranges). Analysis of variance was used to compare the rates of TEM combined with EM (especially OEM) and those of other gynecological diseases. P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. All data were processed using SAS 9.0 statistical software (SAS Institute, Inc.).

There were 1982 patients diagnosed with EM at our hospital who underwent laparoscopic surgery, including salpingectomy, cystectomy, and adenomyomectomy, and 30 of these patients were diagnosed with TEM, accounting for 1.51% of the patients (30/1982). Laparoscopic surgery was performed in all 30 TEM patients, including unilateral or bilateral salpingectomy in 27 and tubal cystectomy in 3. The mean age of the 30 TEM patients was 41.13 ± 10.33 years (14-74 years), and 1 of them was postmenopausal. There were 5 patients under 35 years old, 24 patients between 35 and 50 years old, and 1 patient over 50 years old. The mean number of pregnancies in the 30 patients was 1.23 ± 1.04 (0~4), including 0 pregnancies in 11 patients, 1 in 17 patients, and > 1 in 2 patients. The average number of births was 0.70 ± 0.60 (0-2), including 0 births in 11 patients, 1 birth in 17 patients, and > 1 births in 2 patients. 16 patients (53.33%) conceived naturally and gave birth to healthy babies.

Three patients had no sexual history, 6 patients had a history of infertility, 12 patients had a history of induced abortion, 13 patients had a history of cesarean section, 1 patient had a history of tubal sterilization, and 4 patients had contraceptive intrauterine devices (IUDs) (Table 1). A total of 20 patients had a history of intrauterine surgery (including induced abortion, cesarean section and IUD insertion).The incidence rate of TEM was higher in patients with an intrauterine operation history than in patients without an intrauterine operation history (P < 0.05). There were 6 patients with a history of a laparoscopic ovarian endometrial cystectomy and 1 patient with a history of a laparoscopic myomectomy.

| Sample number | Age | G/P | Infertility | Intrauterine surgery | CA125 (U/mL) | Pathologic diagnosis | RAF scores of ASRM | ||

| Fallopian tube and/or ovary | Uterine Anomaly | Deep infiltrating endometriosis | |||||||

| 1 | 45 | 1/1 | No | Yes | 53.2 | Absence right fallopian tube and right ovary | Uterus normal | No | 52 |

| 2 | 35 | 1/0 | Yes | Yes | 80.2 | Absence left fallopian tube and left ovary | Uterus normal | Yes | 82 |

| 3 | 46 | 2/1 | No | Yes | 10.2 | Absence left fallopian tube | Uterine myoma | No | 36 |

| 4 | 44 | 1/1 | No | No | 131.7 | Absence left fallopian tube and left ovary | Uterus normal | No | 82 |

| 5 | 27 | 0/0 | No | No | 52.1 | Absence left fallopian tube and left ovary | Uterus normal | Yes | 74 |

| 6 | 44 | 2/1 | No | Yes | 233.5 | Absence left fallopian tube and left ovary | Uterine myoma | Yes | 94 |

| 7 | 25 | 1/0 | No | Yes | 78.6 | Absence left fallopian tube and left ovary | Uterus normal | No | 92 |

| 8 | 48 | 1/1 | No | Yes | 49.9 | Absence left fallopian tube and left ovary | Uterine myoma | No | 92 |

| 9 | 40 | 3/2 | No | Yes | 49.3 | Absence left fallopian tube and left ovary | Uterine sarcoma | Yes | 48 |

| 10 | 47 | 1/1 | No | No | 21.3 | Absence left fallopian tube and left ovary | Uterus normal | No | 19 |

| 11 | 41 | 3/0 | Yes | Yes | 205.1 | Absence bilateral fallopian tube and bilateral ovary | Uterus normal | Yes (rectal endometriosis) | 150 |

| 12 | 28 | 0/0 | No | No | 102.6 | Absence left fallopian tube and bilateral ovary | Uterus normal | Yes (ureteral endometriosis) | 82 |

| 13 | 47 | 2/1 | No | Yes | 95.7 | Absence bilateral fallopian tube and bilateral ovary | Uterine myoma | Yes | 150 |

| 14 | 47 | 0/0 | Yes | No | 29.3 | Absence left fallopian tube and left ovary | Uterine adenomyosis | No | 92 |

| 15 | 28 | 0/0 | No | No | 168.5 | Absence left fallopian tube and left ovary | Uterus normal | Yes (ureteral endometriosis) | 144 |

| 16 | 74 | 2/2 | No | Yes | 10.1 | Absence left fallopian tube and left ovary | Uterus normal | No | 64 |

| 17 | 49 | 1/0 | Yes | Yes | 498.7 | Absence bilateral fallopian tube and bilateral ovary | Uterine adenomyosis | Yes | 144 |

| 18 | 49 | 3/1 | No | Yes | 45.2 | Absence right fallopian tube and right ovary | Uterus normal | No | 52 |

| 19 | 43 | 1/1 | No | Yes | 31.9 | Absence right fallopian tube and right ovary | Uterine myoma | No | 80 |

| 20 | 43 | 1/1 | No | Yes | 18.2 | Absence left fallopian tube and left ovary | Uterine adenomyosis | No | 116 |

| 21 | 40 | 1/1 | No | Yes | 28.8 | Absence left fallopian tube and left ovary | Uterine myoma | Yes | 92 |

| 22 | 42 | 1/1 | No | No | 105 | Absence left fallopian tube and left ovary | Uterus normal | Yes | 76 |

| 23 | 45 | 0/0 | Yes | No | 8.7 | Absence right fallopian tube and left ovary | Uterus normal | Yes | 76 |

| 24 | 47 | 1/1 | No | Yes | 60.3 | Absence left fallopian tube and left ovary | Uterus normal | No | 56 |

| 25 | 39 | 1/1 | No | Yes | 8.6 | Absence bilateral fallopian tube and bilateral ovary | Uterus normal | No | 114 |

| 26 | 42 | 4/1 | No | Yes | 175.8 | Absence left fallopian tube and left ovary | Septate Uterus | No | 92 |

| 27 | 42 | 1/1 | No | Yes | 64.6 | Absence right fallopian tube and right ovary | Uterus normal | No | 36 |

| 28 | 37 | 0/0 | Yes | No | 159.7 | Absence right fallopian tube | Uterus normal | No | 24 |

| 29 | 14 | 0/0 | No | No | 118.5 | Absence left fallopian tube and left ovary | Left uterus unicomis and right rudimentary uterus horn | Yes | 82 |

| 30 | 36 | 2/1 | No | Yes | 17.5 | Absence right fallopian tube and right ovary | Uterine adenomyosis | No | 62 |

Among the 30 patients, 9 patients had a chief complaint of progressive dysmenorrhea, 5 patients had chronic abdominal pain, 4 patients had menorrhagia, 6 patients had infertility, 3 patients had abnormal vaginal bleeding, and 15 patients were diagnosed with adnexal cysts by ultrasound. Of the 30 patients, 26 had dysmenorrhea. Preoperative ultrasound revealed that 9 patients had fallopian tube occupation, including 7 patients with suspected hydrosalpinx and 2 patients with undetermined fallopian tube occupation (suspected cancer). There were 19 patients (63.33%) who had a CA125 level over 35 U/mL, with an average level of 90.43 ± 98.95 U/mL.

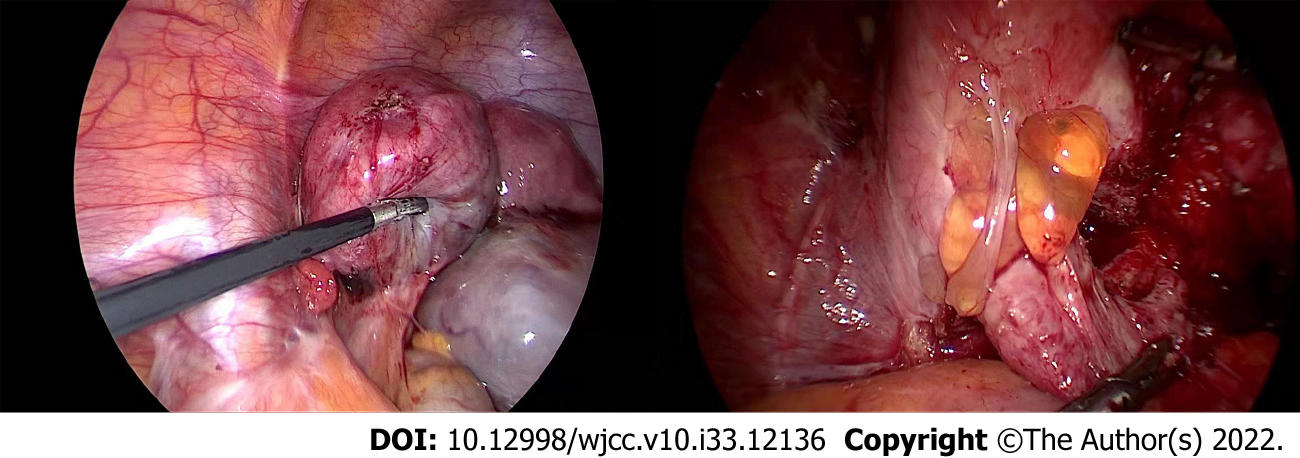

Laparoscopic surgery was performed in all 30 TEM patients, including unilateral or bilateral salpingectomy in 27 and tubal cystectomy in 3. There were fallopian tubal abnormalities in 26 patients, including hydrosalpinx in 22 patients, unilateral or bilateral fallopian tubal and ovarian adhesion and hydrosapinx, tubal torsion and thickening of the fallopian tube in 10 patients, unilateral or bilateral distorted and enlarged fallopian tubes with violet lesions in 7 patients, unilateral or bilateral fallopian tube fimbria embedment in 5 patients, bilateral fallopian tube ampullary enlargement and stiffness with a history of bilateral tubal ligation in 1 patient, and unilateral or bilateral endometrial fallopian tubal cyst in 3 patients. There were 26 patients with EM in other parts of the pelvic cavity, 11 patients with uterine myoma, and 1 patient with uterine malformation (rudimentary uterus horn). The size and diameter of the lesions were noted to be 0.5-10 cm during intraoperative exploration. Clinical staging was performed for endometriotic lesions in other parts of the pelvic cavity. The RAF scores of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) staging ranged between 19 and 150 points, with an average score of 81.83 ± 35.14 points. There were 0 cases in stage I, 0 cases in stage II, 4 cases in stage III and 26 cases in stage IV (Figures 1 and 2).

Postoperative pathology confirmed unilateral TEM in 26 cases and bilateral TEM in 4 cases. Endo

Only 2 patients had simple TEM, had no symptoms and were diagnosed with adnexal cysts by ultrasound. The remaining patients had one or more lesions, including other pelvic EM lesions in 26 patients (13 cases of OEM cysts and 13 cases of OEM accompanied by pelvic EM). The EM lesions that were in unilateral fallopian tubes and unilateral ovaries were all ipsilateral. There were 4 cases accompanied by adenomyosis, 5 cases with uterine myoma and 1 case with uterine sarcoma. A patient with left TEM combined with left rudimentary uterus horn and left OEM cyst underwent a laparoscopic left hysterectomy, a left salpingectomy and a left ovarian endometrial cystectomy (Table 1).

In our study, the rate of TEM combined with EM (especially OEM) was higher than the rates of other gynecological diseases (P = 0.0001). The TEM lesions of 4 patients who had no obvious abnormal appearance of their fallopian tubes were detected in the muscularis and mucosa of the fallopian tube (0.5-5 mm). The TEM lesions of 26 patients who had abnormal appearances of their fallopian tubes were mainly found in the serosa and the muscularis of the fallopian tubes.

In our study, 1982 patients, including 30 patients [1.51% (30/1982)] with TEM, were diagnosed with EM by surgery at our hospital during the same period. In a review of 2063 EM cases published in 1945 by Clement et al[5], EM lesions were located in the fallopian tube in 6 cases, accounting for 0.29% of the patients. There are few reports on TEM, and the incidence rate of TEM has varied greatly. This may be related to the fact that the clinical characteristics of TEM are not obvious and that the diagnosis of TEM requires surgical and pathological diagnostic verification. In recent years, with the promotion of the concept of preventive salpingectomy during hysterectomy, TEM was found in the postoperative pathological examinations of fallopian tubes without any obvious abnormalities. Therefore, more large-sample data and epidemiological investigations are needed to determine the exact incidence rate of TEM.

TEM lesions can be divided into three types: serosal (subserosal) TEM, intraluminal TEM and past-tubal ligation TEM. The most common type of TEM is serosal (subserosal) TEM, which is frequently accompanied by EM in other parts of the pelvis. Intrauterine surgery increases the incidence of EM, which may increase the incidence rate of TEM[6]. Most of the patients had a history of intrauterine surgery and tubal ligation, indicating that tubal ligation and intrauterine surgery may increase the incidence rate of TEM. In 1981, Rock et al[7] reported that the incidence of TEM could be as high as 63% after laparoscopic tubal electrocoagulation sterilization. The mechanism of the induction of TEM after tubal ligation may be related to the following three factors[8]: (1) Fistulas formed by tubal ligation may induce endometrial implantation directly; (2) the position of the tubal ligation is located between the isthmus and ampulla. Ligation stimulates the activation of the tubal intima, incurs tubal submucosa, muscularity and serosa to convert into or tends to transform into endometrial tissue, and finally forms lesions; and (3) factors related to infection may cause EM lesions to directly invade the fallopian tube, leading to TEM and changes in the fallopian tube structure, or TEM may be indirectly caused by the inflammatory response. In addition, the pathogenic factors of EM, such as menstrual reflux and genetic factors, may also be applicable to TEM[9] However, further study is needed to confirm this.

TEM lacks specific clinical manifestations. Routine examinations (e.g., ultrasound studies and serum tumor marker measurements) cannot be used to obtain a definite diagnosis[10]. None of the cases reported in China or in our study were diagnosed before surgery. McGuinness et al[11] found that TEM was more common than we expected. In patients with pelvic pain, adnexal cysts or infertility, 12% of the patients had visible tubal lesions through laparoscopic surgery, and 42.5% had only microscopic lesions confirmed by postoperative pathology. There are no separate clinical staging criteria for TEM. The modified revised American Fertility Society staging criteria of the ASRM can be used for reference. The EM was scored according to the lesion location, size, scope and adhesion of EM lesions to evaluate the severity of the disease and to select treatment plans.

Different parts of the fallopian tube may cause different clinical manifestations[12]: (1) If the lesion involves the isthmus or interstitium of the fallopian tube, the lesion can cause infertility by proximal fallopian tube obstruction; (2) lesions involving the middle fallopian tube are rare and are more common in patients with severe EM; and (3) if the lesion involves the ampulla of the fallopian tube, it will lead to obstruction and cause hydrops and blood accumulation and will also cause local diverticulum formation or thickening and distortion of the fallopian tube, which can eventually lead to infertility or dysmenorrhea.

Prospective studies have shown that EM is associated with an increased risk of subsequent infertility[13]. However, among patients with histologically confirmed EM, those patients who were confirmed to have OEM did not have a higher risk of infertility[4]. These results suggest that TEM and other types of EM may be more correlated with infertility[14].

Among the 30 included patients, 26 had dysmenorrhea, 5 had chronic abdominal pain, and 6 had infertility. Preoperative gynecological ultrasound examinations revealed 9 cases of fallopian tube occupation, including 7 cases of suspected hydrosalpinx and 2 cases of undetermined fallopian tube occupation (suspected cancer). If a patient has the clinical symptoms of dysmenorrhea or infertility, salpingography and laparoscopic exploration should be recommended, even if the ultrasound examination only suggests the existence of OEM, to determine whether there are fallopian tube structure abnormalities and to detect and manage the possible coexisting TEM[10].

EM is closely associated with the occurrence of EM-associated ovarian cancer, especially endo

As one category of EM, TEM is treated following the general principles for the treatment of EM, including reducing and removing lesions, relieving and controlling pain, treating and promoting fertility, and preventing and reducing recurrence[19].

TEM is often detected during laparoscopic exploration of OEM or other pelvic lesions. Surgery, drugs and combination therapy can be used simultaneously. If the patient desires fertility preservation, conservative surgery, such as salpingography and laparoscopic salpingoplasty, can be used according to the lesion site. During the operation, attention should be given to the prevention of adhesions, such as the use of anti-adhesion agents or anti-adhesion membranes (Interceed®). No bleeding should be found on the wound surface; otherwise, the adhesions will be more serious[12,20], and postoperative GnRH-a therapy may be needed. The fallopian tube on the lesion side should be removed if the patient has no desire for fertility preservation or if the patient should need to undergo a hysterectomy because of other gynecological diseases. According to the guidelines for the treatment of EM, combined drug therapy is recommended after surgery to reduce EM recurrence.

In addition, assisted reproductive technology, especially gamete intrafallopian transfer, can significantly increase the rate of intrauterine pregnancy[21].

In our study, 2 patients had simple TEM; the rest had one or more lesions, including 26 patients with pelvic EM in other areas (13 with OEM cysts and 13 with OEM and pelvic EM). The EM lesions of the unilateral fallopian tube and unilateral ovary were ipsilateral. There were 4 cases of adenomyosis, 5 cases of uterine myoma and 1 case of uterine sarcoma. One patient had left TEM combined with a left rudimentary uterine horn and a left OEM cyst. The rate of TEM combined with EM (especially OEM) was higher than that of other gynecological diseases (P = 0.0001), which indicates that TEM is related to OEM.

Zheng et al[22] reported the oviduct source of OEM. Their team validated FM03 and DMBT1 as specific markers for tubal mucosal epithelium and endometrium, respectively, in 32 cases of OEM. The results showed that FM03 expression was high and DMBT1 expression was low in 18 patients (56%). Fourteen patients (44%) had low FM03 expression and high DMBT1 expression. The results showed that approximately 60% of the cells in EM were derived from the fallopian tubes, and 40% were derived from the uterus. The histological origin of OEM may be the tubal epithelium[23]. The results of this study also indicate that TEM and OEM may have a certain correlation. The etiology of TEM has not been determined thus far, but it may be associated with OEM. This is an original perspective to some extent, but a large number of clinical studies are needed to verify it.

Xue et al[24] found that there were 168 cases (55.08%) of left TEM, 93 cases (30.49%) of right TEM, and 44 cases (14.43%) of bilateral TEM among 305 TEM patients. They believed that TEM is an asymmetrical disease and that the left side is more susceptible. However, in our study, a left-sided susceptibility to TEM was not found due to the limited sample size. These perspectives are new. A large number of scientific studies and clinical studies are still needed for verification.

This study is limited by several factors. First, the sample size, constituting 1982 patients with EM and 30 with identifiable TEM, was small. Second, owing to the study’s retrospective nature, it was difficult to assess the significance of salpingectomy in postoperative pain relief in patients with tubal disease, especially because all patients had EM on other pelvic organs as well.

The fields of infertility and EM management would benefit from further studies that evaluate the role of fallopian tubes and the anatomical location of EM lesions in patients with infertility and pelvic pain.

The pathogenesis and mechanism of TEM have not been determined, but the correlation between TEM and OEM remains to be studied. The treatment of EM may help to increase the natural pregnancy rates, but further studies are needed for confirmation. The study of TEM will provide new ideas for the treatment of female infertility and other diseases and thus has very important clinical significance.

Tubal endometriosis (TEM) is characterized by ectopic endometrial glands and/or stroma within any part of the fallopian tube. TEM is difficult to diagnose during surgery and is usually detected by pathology after surgery.

The fields of infertility and EM management would benefit from further studies that evaluate the role of fallopian tubes and the anatomical location of endometriosis (EM) lesions in patients with infertility and pelvic pain.

To provide a clinical basis for the diagnosis and treatment of TEM.

In this study, the data of 30 patients who underwent laparoscopic salpingectomy due to various gynecological diseases and had pathological confirmation of TEM at our hospital were retrospectively analyzed, and the clinical basis for the diagnosis and treatment of TEM was evaluated.

Pathology showed that only 2 patients had TEM without any other gynecological diseases, the rest had one or more lesions. The EM lesions of the unilateral fallopian tube and unilateral ovary were ipsilateral. One patient had left TEM combined with a left rudimentary uterine horn and a left ovarian endometriosis (OEM) cyst. The rate of TEM combined with EM (especially OEM) was higher than that of other gynecological diseases (P = 0.0001), which indicates that TEM is related to OEM.

The final diagnosis of TEM depends on pathological examination since there are no specific clinical characteristics. The pathogenesis and mechanism of TEM have not been determined, but the correlation between TEM and OEM remains to be studied. The treatment of EM may help to increase the natural pregnancy rates, but further studies are needed for confirmation.

The study of TEM will provide new ideas for the treatment of female infertility and other diseases and thus has very important clinical significance.

The authors thank the Ruijin Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine for their assistance with this research.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Obstetrics and gynecology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Jin X, China; Naem AA, Germany S-Editor: Zhang H L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhang H

| 1. | Hill CJ, Fakhreldin M, Maclean A, Dobson L, Nancarrow L, Bradfield A, Choi F, Daley D, Tempest N, Hapangama DK. Endometriosis and the Fallopian Tubes: Theories of Origin and Clinical Implications. J Clin Med. 2020;9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Foti PV, Ognibene N, Spadola S, Caltabiano R, Farina R, Palmucci S, Milone P, Ettorre GC. Non-neoplastic diseases of the fallopian tube: MR imaging with emphasis on diffusion-weighted imaging. Insights Imaging. 2016;7:311-327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Yuan Z, Wang L, Wang Y, Zhang T, Li L, Cragun JM, Chambers SK, Kong B, Zheng W. Tubal origin of ovarian endometriosis. Mod Pathol. 2014;27:1154-1162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Boujenah J, Salakos E, Pinto M, Shore J, Sifer C, Poncelet C, Bricou A. Endometriosis and uterine malformations: infertility may increase severity of endometriosis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2017;96:702-706. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Clement PB. The pathology of endometriosis: a survey of the many faces of a common disease emphasizing diagnostic pitfalls and unusual and newly appreciated aspects. Adv Anat Pathol. 2007;14:241-260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 217] [Cited by in RCA: 214] [Article Influence: 11.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Tomassetti C, Geysenbergh B, Meuleman C, Timmerman D, Fieuws S, D'Hooghe T. External validation of the endometriosis fertility index (EFI) staging system for predicting non-ART pregnancy after endometriosis surgery. Hum Reprod. 2013;28:1280-1288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Rock JA, Parmley TH, King TM, Laufe LE, Su BS. Endometriosis and the development of tuboperitoneal fistulas after tubal ligation. Fertil Steril. 1981;35:16-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Zhang XS, Lin J. Clinical analysis of 21 cases with tubal endometriosis. Prog Obstet Gynecol. 2002;B: 265-267. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Daraï E, Ploteau S, Ballester M, Bendifallah S. [Pathogenesis, genetics and diagnosis of endometriosis]. Presse Med. 2017;46:1156-1165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Qi H, Zhang H, Zhao X, Qin Y, Liang G, He X, Zhang J. Integrated analysis of mRNA and protein expression profiling in tubal endometriosis. Reproduction. 2020;159:601-614. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | McGuinness B, Nezhat F, Ursillo L, Akerman M, Vintzileos W, White M. Fallopian tube endometriosis in women undergoing operative video laparoscopy and its clinical implications. Fertil Steril. 2020;114:1040-1048. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Zheng X, Han H, Guan J. Clinical features of fallopian tube accessory ostium and outcomes after laparoscopic treatment. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2015;129:260-263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Prescott J, Farland LV, Tobias DK, Gaskins AJ, Spiegelman D, Chavarro JE, Rich-Edwards JW, Barbieri RL, Missmer SA. A prospective cohort study of endometriosis and subsequent risk of infertility. Hum Reprod. 2016;31:1475-1482. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 176] [Article Influence: 19.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Mahran A, Abdelraheim AR, Eissa A, Gadelrab M. Does laparoscopy still has a role in modern fertility practice? Int J Reprod Biomed. 2017;15:787-794. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Wei JJ, William J, Bulun S. Endometriosis and ovarian cancer: a review of clinical, pathologic, and molecular aspects. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2011;30:553-568. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Dawson A, Fernandez ML, Anglesio M, Yong PJ, Carey MS. Endometriosis and endometriosis-associated cancers: new insights into the molecular mechanisms of ovarian cancer development. Ecancermedicalscience. 2018;12:803. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Chiang AJ, Chang C, Huang CH, Huang WC, Kan YY, Chen J. Risk factors in progression from endometriosis to ovarian cancer: a cohort study based on medical insurance data. J Gynecol Oncol. 2018;29:e28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Higashiura Y, Kajihara H, Shigetomi H, Kobayashi H. Identification of multiple pathways involved in the malignant transformation of endometriosis (Review). Oncol Lett. 2012;4:3-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ferrero S, Vellone VG, Barra F. Pathophysiology of pain in patients with peritoneal endometriosis. Ann Transl Med. 2019;7:S8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Goldberg JM, Falcone T, Diamond MP. Current controversies in tubal disease, endometriosis, and pelvic adhesion. Fertil Steril. 2019;112:417-425. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Wiedemann R, Sterzik K, Gombisch V, Stuckensen J, Montag M. Beyond recanalizing proximal tube occlusion: the argument for further diagnosis and classification. Hum Reprod. 1996;11:986-991. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Zheng W, Li N, Wang J, Ulukus EC, Ulukus M, Arici A, Liang SX. Initial endometriosis showing direct morphologic evidence of metaplasia in the pathogenesis of ovarian endometriosis. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2005;24:164-172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Wang Y, Mang M, Wang Y, Wang L, Klein R, Kong B, Zheng W. Tubal origin of ovarian endometriosis and clear cell and endometrioid carcinoma. Am J Cancer Res. 2015;5:869-879. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Xue RH, Li J, Huang Z, Li ZZ, Chen L, Lin Q, Huang HF. Is tubal endometriosis an asymmetric disease? Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2020;301:721-727. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |