Published online Nov 6, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i31.11630

Peer-review started: July 22, 2022

First decision: August 22, 2022

Revised: August 23, 2022

Accepted: September 22, 2022

Article in press: September 22, 2022

Published online: November 6, 2022

Processing time: 97 Days and 1.3 Hours

Craniofacial necrotizing fasciitis (CNF) is an uncommon but fatal infection that can spread rapidly through the subfascial planes in the head and neck region. Symptoms usually progress rapidly, and early management is necessary to optimize outcomes.

A 43-year-old man visited our hospital with left hemifacial swelling involving the buccal and submandibular areas. The patient had fever for approximately 10 d before visiting the hospital, but did not report any other systemic symptoms. Computed tomography scan demonstrated an abscess with gas formation. After surgical drainage of the facial abscess, the patient’s systemic condition worsened and progressed to septic shock. Further examination revealed pulmonary and renal abscesses. Renal percutaneous catheter drainage was performed at the renal abscess site, which caused improvement of symptoms. The patient showed no evidence of systemic complications during the 4-mo post-operative follow-up period.

As the patient did not improve with conventional CNF treatment and symptoms only resolved after controlling the infection, the final diagnosis was secondary CNF with septic emboli. Aggressive surgical decompression is important for CNF management. However, if symptoms worsen despite early diagnosis and management, such as pus drainage and surgical intervention, clinicians should consider the possibility of a secondary abscess from internal organs.

Core Tip: Craniofacial necrotizing fasciitis (CNF) is a severe infection that can rapidly spread and progress to life-threatening conditions; therefore, early diagnosis and appropriate management are essential. It can occur mainly due to odontogenic infection, but many other causes lead to development of symptoms. This report describes a rare case of secondary necrotizing fasciitis originating from internal organ abscesses. It should be considered that septic emboli from other internal organs can cause a secondary CNF if there is no improvement of symptoms after radical surgical management.

- Citation: Lee DW, Kwak SH, Choi HJ. Secondary craniofacial necrotizing fasciitis from a distant septic emboli: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(31): 11630-11637

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i31/11630.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i31.11630

Craniofacial necrotizing fasciitis (CNF) is a rare and life-threatening condition characterized by the rapid progressive necrosis of the fascia, fat, and muscle. Fascial necrosis is a key feature of the disease progression. CNF is a lethal disease with a mortality rate of 20%-40%[1]. Although CNFs are rare, they are often associated with systemic conditions owing to the abundant vascularity of the head and neck region. Based on a literature review, CNF is mainly caused by odontogenic infections after tooth extraction, especially in patients with chronic diseases such as diabetes, immunosuppression, and elderly patients[2]. It can also be caused by peritonsillar abscesses, skin trauma due to insect bites, and fractures[3]. In most wound cultures of necrotizing fasciitis, group A Streptococcus bacteria are the most common pathogens[4,5]. Management of necrotizing fasciitis includes early detection, broad-spectrum antibiotics, and most importantly, radical surgical management. Early detection of CNF can depend on findings such as air bubbles in soft tissues on computed tomography (CT) and rapid progression of infection. The use of appropriate antibiotics based on bacterial cultures is vital in improving patient conditions[6]. However, CNFs are frequently difficult to manage despite aggressive treatment; thus, leading to significant morbidity and potential mortality[7].

In this report, we describe a rare case of CNF as a secondary presentation in a 43-year-old male patient who developed necrotizing fasciitis due to hematogenic spread from lung and renal abscesses. This patient met the diagnostic criteria of necrotizing fasciitis, unlike Ludwig’s angina which is bilateral inflammation that invades the submandibular area, including evidence of necrotizing fascia, characteristic pathological features (extensive tissue necrosis, pattern of infection spreading along the fascia), and/or the clinical presentation of gas-forming air bubbles in the fascia or muscle necrosis invasion on imaging tests such as contrast-enhanced CT[8].

A 43-year-old man visited our hospital with left facial swelling involving the buccal and submandibular areas.

A 43-year-old male patient was admitted to our outpatient department complaining of swelling and pain in the left hemifacial area which started two weeks prior to consult. The patient had fever for approximately 10 d, but no other systemic symptoms occurred. At the time of the visit, the patient had fever with a temperature of 38.0 °C.

The patient was diagnosed with diabetes mellitus treated with insulin. In addition, the patient had no history of illness associated with CNF, such as dental procedures, including tooth extraction, skin trauma, head and neck infections, and other facial fractures.

The patient had no medical history other than diabetes mellitus, and no family history of CNF.

Preoperative: On physical examination, trismus and thinning of the skin with crepitation were observed on the left cheek. There were also no pathological findings on dental examination.

Postoperative: On postoperative day (POD) 1, after surgical decompression by incision and drainage, the patient’s systemic condition worsened, accompanied by tachycardia, hypotension, and overall deterioration of the patient’s condition; hence, septic shock was considered.

At the time of hospitalization, the glycated hemoglobin (HbA1C) level was elevated at 17.1, indicating uncontrolled diabetes. The Laboratory Risk Indicator for Necrotizing Fasciitis (LRINEC) scoring system was used for proper diagnosis of necrotizing fasciitis[9]. Laboratory findings showed a high white blood cell (WBC) count (15170/μL; LRINEC score 1 point), a low hemoglobin level (10.5 g/dL; LRINEC score 2 points), an elevated high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) level (212.94 mg/L; LRINEC score 4 points), a high glucose level (242 mg/dL; LRINEC score 1 point), and a slightly low sodium level (134 mmol/L; LRINEC score 2 points). The following results were normal: Creatinine, bilirubin, aspartate aminotransferase, and alanine aminotransferase. The patient had a score of 10 points in the LRINEC, indicating a high risk of CNF[9]. In addition, the albumin level was low at 2.3 g/dL. Procalcitonin, measured on the 3rd d after admission, was elevated at 1.140 ng/mL (normal range: < 0.1 ng/mL). Blood cultures after admission, wound swabs, and tissue cultures of the surgical field showed gram-negative Klebsiella pneumoniae (K. pneumoniae).

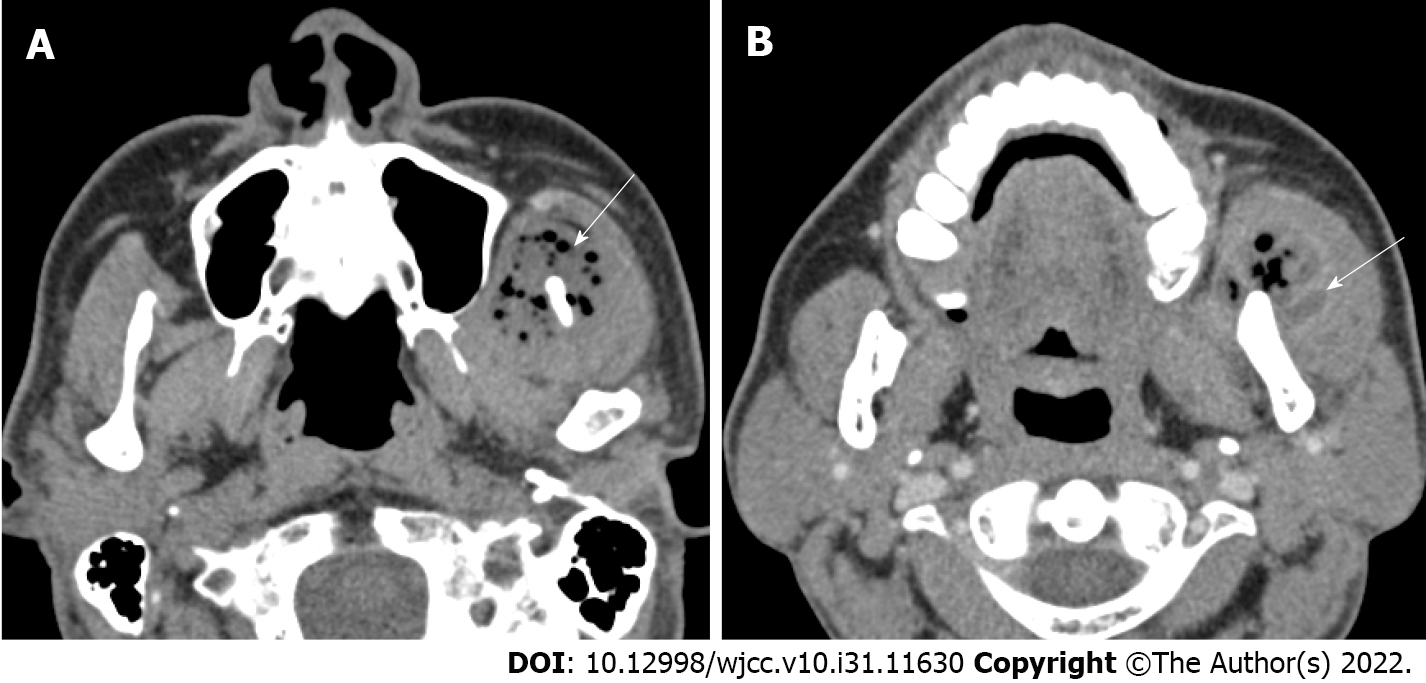

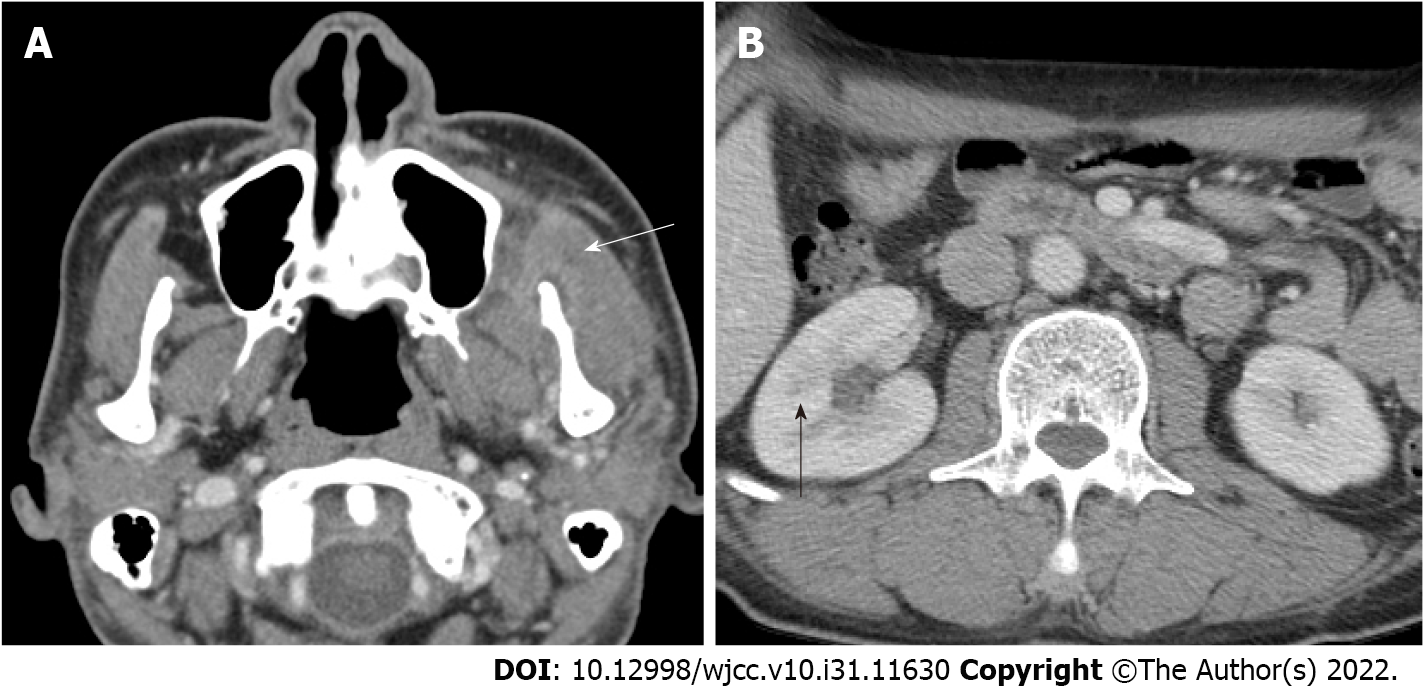

Preoperative: On facial CT, multiple abscesses with air bubble in the left temporal, masticator, and buccal spaces along the fascial layer were observed (Figure 1A). Pleomorphic wall-enhancing lesions were also observed in the left masseter and temporalis muscles (Figure 1B).

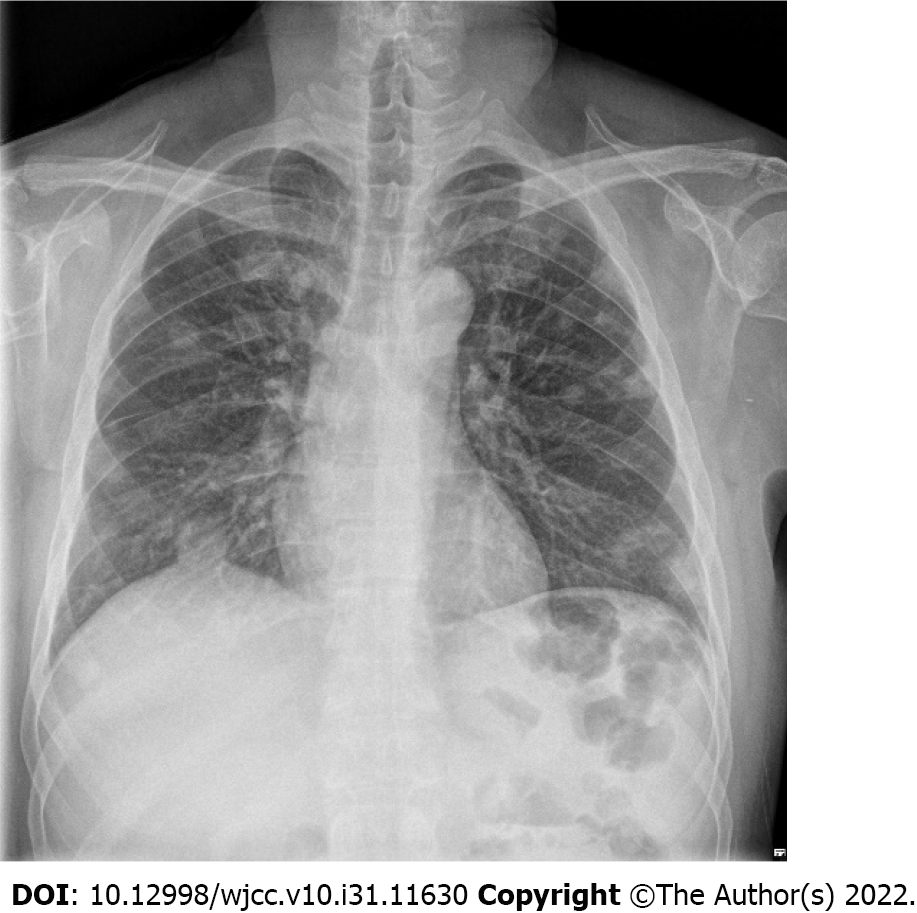

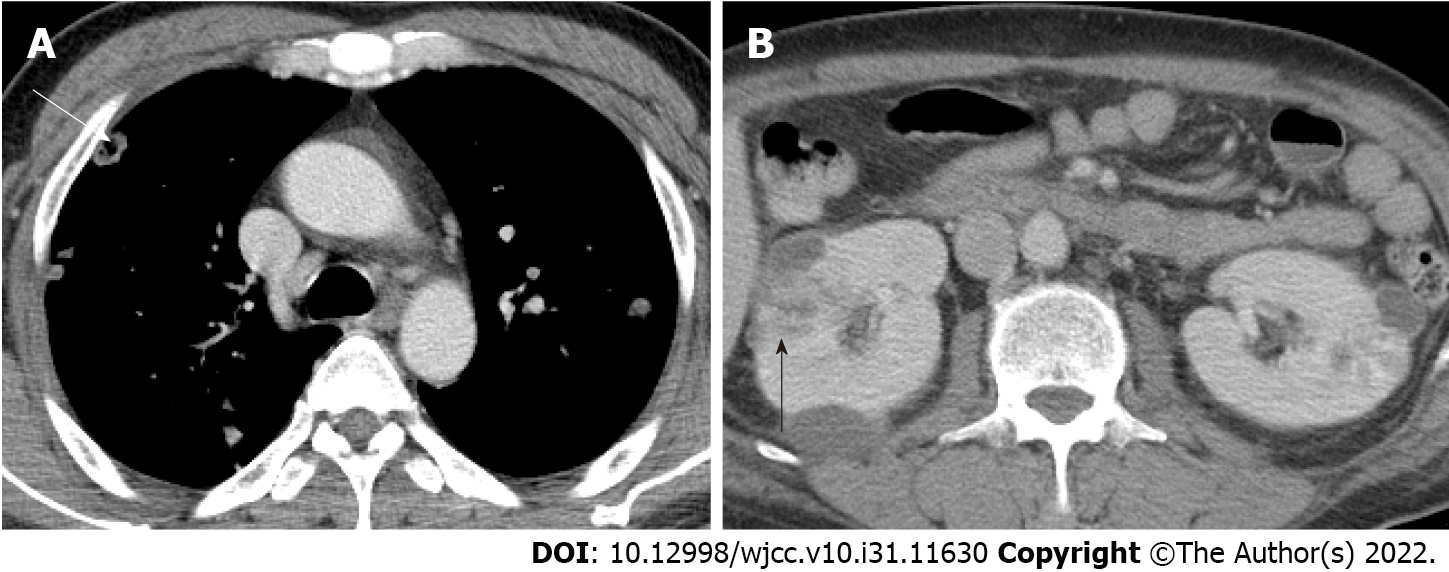

Postoperative: On POD 1, follow-up CT revealed that the abscess pocket had become smaller. However, after decompression of the CNF, the patient’s general condition deteriorated and progressed to septic shock. Contrast-enhanced chest CT was performed because multiple nodules were observed on chest X-ray upon admission (Figure 2). On chest CT on POD 2, septic emboli and pneumonia were observed in both lungs (Figure 3A). In addition, a lesion suspected as renal abscess was observed on chest CT. On POD 3, contrast-enhanced abdominopelvic CT (APCT) was also done, which showed multiple variably-sized renal abscesses in both kidneys (Figure 3B). This raised the suspicion that septic pneumonia and renal abscesses were the sources of sepsis.

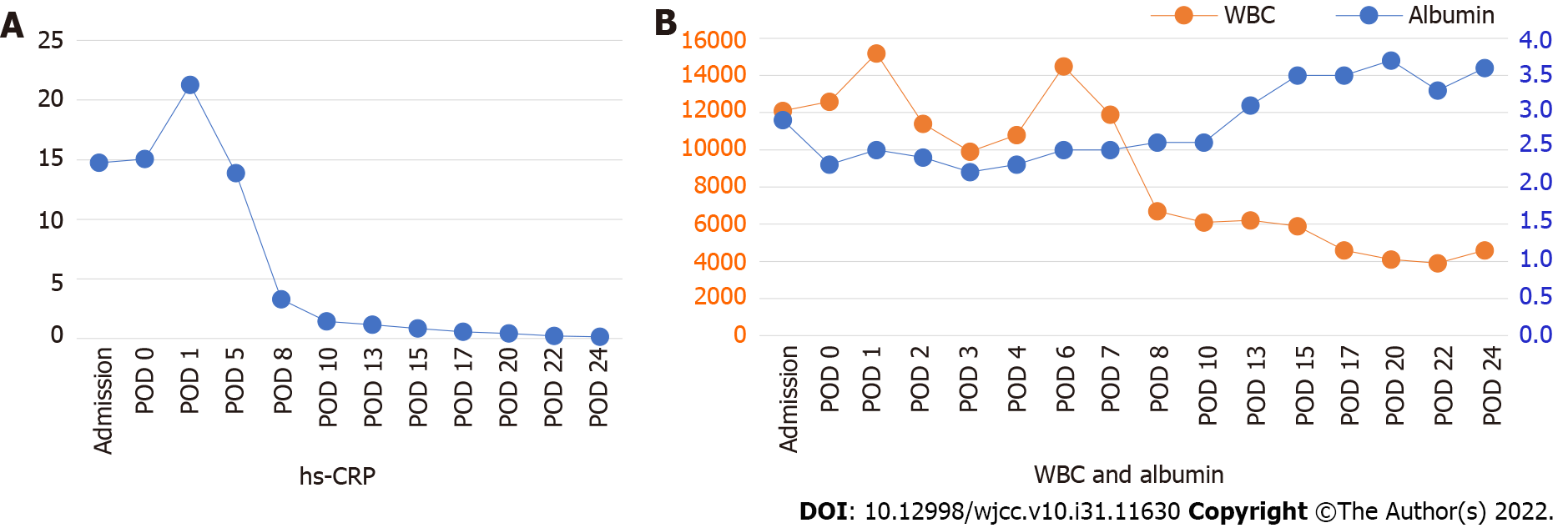

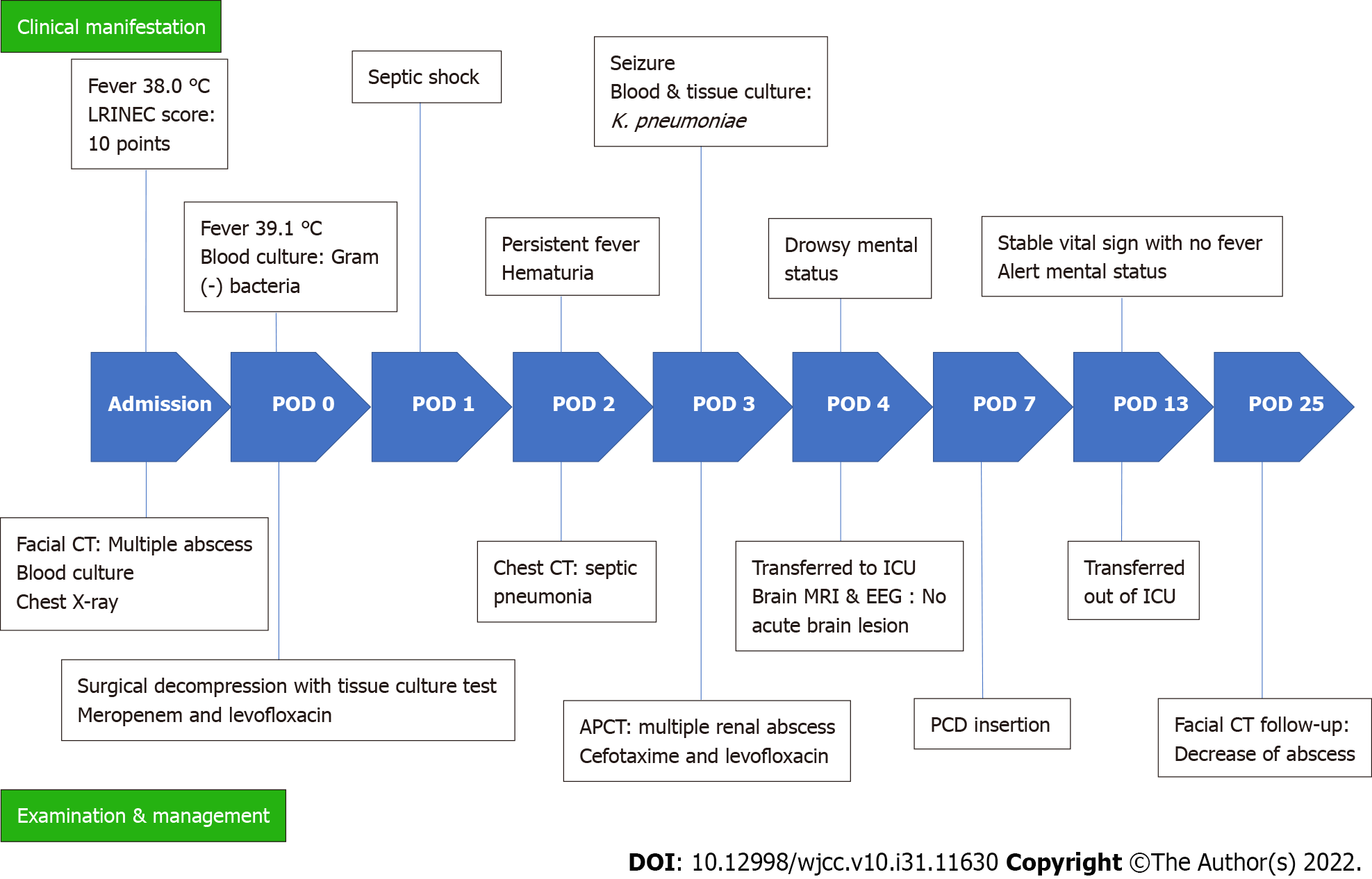

Prior to blood culture results for identification of sepsis, intravenous antibiotics were shifted to meropenem 1 g every 8 h and levofloxacin 750 mg per day, after consultation with the Department of Infectious Diseases. On POD 2, after K. pneumoniae was identified from the blood culture and detection of septic pneumonia and renal abscess, the antibiotic was changed to cefotaxime (POD 3). Cytopenia due to sepsis persisted, and despite the addition of metronidazole (POD 6), the clinical symptoms did not improve. On POD 3, the patient developed seizures due to metabolic encephalopathy, but magnetic resonance imaging or electroencephalography showed no acute brain lesions. Renal percutaneous catheter drainage (PCD) was performed on POD 7 to treat the renal abscess. After PCD insertion, the clinical signs and laboratory findings improved rapidly (Figure 4). After two weeks of PCD, the signs of infection and laboratory findings gradually stabilized, and the abscesses of the left masseter and temporalis muscle further decreased in size on facial CT taken on POD 25 (Figure 5A). Figure 6 shows a timeline of the course of illness.

The patient’s CNF symptoms and septic condition did not improve after surgical decompression of CNF but improved rapidly after PCD. Therefore, the final diagnosis of this patient was secondary CNF due to septic pulmonary and renal emboli.

Under urgent general anesthesia, an incision was made transversely above the left temporal crest. The superficial and deep temporal fasciae were dissected and the temporalis muscle was identified. After confirming the position of the abscess pocket on CT, dissection of the temporalis muscle was performed to drain the abscess, followed by massive saline irrigation. A drainage line was inserted through the temporal incision into the abscess pocket. A left upper gingivobuccal sulcus incision was then made to drain the abscess pocket of the masseter muscle and the pre-zygomatic area.

Intravenous empiric antibiotics were initially given, and after detection of K. pneumoniae, the appropriate antibiotic was administered based on the sensitivity results of the culture strain. The patient did not show improvement in clinical symptoms even after the administration of meropenem, levofloxacin, cefataxime, or metrodidazole, but eventually showed rapid improvement after PCD insertion. After PCD insertion, the antibiotic was again changed to ceftriaxone (2 g/d). In addition, since the patient had uncontrolled diabetes mellitus with a significantly elevated HbA1C level at the time of admission, blood glucose tests were monitored daily, and blood glucose was controlled with insulin. No further surgical procedures were performed after PCD insertion, and the patient was discharged on the POD 28 after blood glucose control, and the infection symptoms completely resolved.

No further renal abscesses were observed on APCT on POD 45 (Figure 5B). At outpatient follow-up after discharge, the patient’s HbA1C decreased to 4.9. Trismus was no longer observed six months after surgical decompression. No other symptoms suggestive of complications were observed in the craniofacial area.

It is easy to overlook CNF especially when only the initial clinical symptoms are present, and it is difficult to differentiate CNF at its initial stage from a simple abscess[10]. However, CNF progresses rapidly and have serious implications. Unlike simple abscesses, CNFs have several specific clinical features, including rapid progression of clinical infectious manifestations, an abscess with disproportionate pain, presence of subcutaneous air bubbles or crepitations, and accompanying hyperesthesia or anesthesia to pinpricks. Air bubble formation in tissues, although not pathognomonic, is a critical sign that may appear on soft tissue plain radiographs or CT scans[11].

CNF may occur as a monomicrobial or polymicrobial infection. Park et al[4] reported that the prognosis of CNF differs according to the gram-staining pattern of the bacterium. Among gram-negative organisms, K. pneumoniae is the second most commonly detected pathogen, and most monomicrobial K. pneumoniae infections have a fatal course[7]. It is a highly virulent pathogen with a high rate of mortality. Most necrotizing fasciitis rapidly progresses due to direct infiltration of bacteria into the lesion; however, in the case of K. pneumoniae, as in this case, necrotizing fasciitis is caused by hematogenous dissemination to a septic lesion with an unknown etiology without a traumatic skin lesion[12].

In the present case, severe infection occurred to the extent that abscesses developed in both the lungs and kidneys. It is difficult to determine the antecedent relationship between the two organs. As the patient’s CNF symptoms did not improve after surgical decompression and the laboratory values worsened and progressed into severe sepsis, craniofacial infection was not the primary cause of sepsis. In addition, considering that the patient’s systemic condition improved dramatically after PCD insertion into the kidney, it was suspected that the infection was renal in origin. The hypervirulent nature of K. pneumoniae induces the formation of multiple abscesses, which may have resulted in secondary CNF, and underlying diseases such as diabetes may have contributed to the spread of septic emboli. Thus, this patient appeared to have developed secondary CNF in the craniofacial area, probably due to an internal organ abscess.

The early diagnosis of CNF in this case was made using the LRINEC score, which can be used to distinguish CNF from severe cellulitis or abscess based on relevant hematologic values. The LRINEC score has been proven useful for detecting severe infections of the upper and lower extremities, which has improved the efficiency of the early diagnosis[13]. Some reports have shown that lower albumin levels in patients are associated with a more fatal prognosis[9,14]. Procalcitonin is synthesized in various tissues and organs in response to bacterial, fungal, and parasitic infections, and it has become a useful marker for determining whether antibiotics should be used for the duration of treatment[15].

This case study has three implications. First, CNF is a possible rare secondary cause of internal organ infections. The most common etiology is odontogenic infection, and skin or blunt trauma have also been reported. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first reported case of secondary CNF caused by septic emboli from an internal organ. Second, the progression of gram-negative K. pneumoniae infection caused a pulmonary or renal abscess, consistent with a previous report showing a higher risk of mortality in cases of sepsis caused by gram-negative pathogens[4]. Third, the patient had no physical examination findings suggestive of an internal organ infection other than fever. However, internal organ abscesses were observed, and despite successful drainage of the CNF, the infection still progressed to septic shock. This suggests that despite absence of other symptoms, the possibility of progression to systemic infection should always be considered if fever is accompanied with low albumin and high WBC count. In cases where a strain of K. pneumoniae is identified and if symptoms do not improve even after surgical decompression, a primary or secondary problem in the internal organs should be investigated further.

CNFs mainly occur after dental procedures; however, it may also be caused by other infections. In the present case, CNF was caused by a systemic infection, which showed a more severe course than a simple abscess or CNF due to other causes. The findings of this study suggest that if CNF is not caused by adjacent skin or teeth, further investigation is indicated to determine the primary source of infection, considering the possibility of an internal organ origin. If the clinical manifestations suggest CNF, active surgical intervention should be performed without delay to reduce the risk of mortality.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Jian X, China; Shelat VG, Singapore S-Editor: Wang JJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wang JJ

| 1. | Golger A, Ching S, Goldsmith CH, Pennie RA, Bain JR. Mortality in patients with necrotizing fasciitis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;119:1803-1807. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Juncar M, Bran S, Juncar RI, Baciut MF, Baciut G, Onisor-Gligor F. Odontogenic cervical necrotizing fasciitis, etiological aspects. Niger J Clin Pract. 2016;19:391-396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Oguz H, Yilmaz MS. Diagnosis and management of necrotizing fasciitis of the head and neck. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2012;14:161-165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Park SY, Yu SN, Lee EJ, Kim T, Jeon MH, Choo EJ, Park S, Chae JW, In Bang H, Kim TH. Monomicrobial gram-negative necrotizing fasciitis: An uncommon but fatal syndrome. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2019;94:183-187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Shin J, Park SI, Cho JT, Jung SN, Byeon J, Seo BF. Necrotizing fasciitis of the masticator space with osteomyelitis of the mandible in an edentulous patient. Arch Craniofac Surg. 2019;20:270-273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ku I, Park JU. Necrotizing fasciitis arisen from nose. Arch Craniofac Surg. 2019;20:279-280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Wong CH, Chang HC, Pasupathy S, Khin LW, Tan JL, Low CO. Necrotizing fasciitis: clinical presentation, microbiology, and determinants of mortality. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85:1454-1460. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Yahav D, Duskin-Bitan H, Eliakim-Raz N, Ben-Zvi H, Shaked H, Goldberg E, Bishara J. Monomicrobial necrotizing fasciitis in a single center: the emergence of Gram-negative bacteria as a common pathogen. Int J Infect Dis. 2014;28:13-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lee DW, Ryu H, Choi HJ, Heo NH. Early diagnosis of craniofacial necrotising fasciitis: Analysis of clinical risk factors. Int Wound J. 2022;19:1071-1084. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Holt GR, Young WC, Aufdemorte T, Mattox DE, Gates GA. Head and neck manifestations of uncommon infectious diseases. Laryngoscope. 1982;92:634-639. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Yamaoka M, Furusawa K, Uematsu T, Yasuda K. Early evaluation of necrotizing fasciitis with use of CT. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1994;22:268-271. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Wang JH, Liu YC, Lee SS, Yen MY, Chen YS, Wang JH, Wann SR, Lin HH. Primary liver abscess due to Klebsiella pneumoniae in Taiwan. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:1434-1438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 424] [Cited by in RCA: 437] [Article Influence: 16.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Su YC, Chen HW, Hong YC, Chen CT, Hsiao CT, Chen IC. Laboratory risk indicator for necrotizing fasciitis score and the outcomes. ANZ J Surg. 2008;78:968-972. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Huang KC, Weng HH, Yang TY, Chang TS, Huang TW, Lee MS. Distribution of Fatal Vibrio Vulnificus Necrotizing Skin and Soft-Tissue Infections: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:e2627. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Wacker C, Prkno A, Brunkhorst FM, Schlattmann P. Procalcitonin as a diagnostic marker for sepsis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:426-435. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 638] [Cited by in RCA: 760] [Article Influence: 63.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |