Published online Jan 21, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i3.891

Peer-review started: March 10, 2021

First decision: October 20, 2021

Revised: November 8, 2021

Accepted: December 21, 2021

Article in press: December 21, 2021

Published online: January 21, 2022

Processing time: 311 Days and 0.6 Hours

Laparoscopic ventral mesh rectopexy (LVMR) continues to be a popular treatment option for rectal prolapse, obstructive defecation/faecal incontinence and rectoceles. In recent years there have been concerns regarding the safety of mesh placements in the pelvis.

To assess the safety of the mesh and the outcome of the procedure.

Eighty-six patients underwent LVMR with Permacol (Biological) mesh from 2012 to 2018 at University Hospital Wishaw. Forty were treated for obstructive defecation secondary to prolapse, rectocele or internal rectal intussusception, 38 for mixed symptoms obstructive defecation and incontinence, 5 for pain and bleeding secondary to full thickness prolapse and 3 with symptoms of incontinence. Questionnaires for the calculation of Wexner scores for constipation and incontinence were completed by the patients who were followed up in the clinic 12 wk after surgery and again in 6-12 mo. The average review of their notes was 18.3 ± 4.2 mo.

The median Wexner scores for constipation pre-operatively and post-operatively were 14.5 [Interquartile range (IQR): 10.5-18.5] and 3 (IQR: 1-6), respectively, while the median Wexner score for faecal incontinence was 11 (IQR: 7-15) and 2 (IQR: 0-5), respectively (P < 0.01). There were 4 (4.6%) recurrences, 2 cases that presented with erosion of a suture through the rectum and one with diskitis. No mesh complications or mortalities were recorded.

LVMR using a Permacol mesh is a safe and effective procedure for the treatment of obstructive defecation/faecal incontinence, rectal prolapse, rectoceles and internal rectal prolapse/intussusception.

Core Tip: Our study adds more evidence to support that laparoscopic mesh rectopexies using biological mesh is a safe and effective procedure and that it significantly improves bowel symptoms of obstructive defecation and faecal incontinence in patients. In our study, there were no mesh related complications, and the recurrence rates were in line with the ones reported in the literature. Although we acknowledge that the direct follow-up period was short, the absence of re-referral of those previously operated patients over the period of 5 years indirectly suggests the safety of the mesh over longer periods.

- Citation: Tsiaousidou A, MacDonald L, Shalli K. Mesh safety in pelvic surgery: Our experience and outcome of biological mesh used in laparoscopic ventral mesh rectopexy. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(3): 891-898

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i3/891.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i3.891

Laparoscopic ventral mesh rectopexy (LVMR) has recently become the preferred treatment for full thickness rectal prolapse, and it has been also widely used in the treatment of rectoceles, enteroceles and rectal intussusception with associated symptoms of obstructive defecation with or without faecal incontinence[1]. The procedure has good short term and long term results with minimum morbidity rates and low recurrence rates[2], particularly when compared to the perineal surgical approach used for treatment of rectal prolapse[2]. In addition, due to reduced postoperative complications, a shorter length of hospital stay is an advantage[1,2].

Over the last few years there have been concerns about the usage of meshes in pelvic surgery, especially since serious complications have been recorded in urogynaecology procedures where trans-vaginal placement of mesh in women was used to treat pelvic organ prolapse. This led many countries to scrutinise the use of mesh. This was particularly the case in the United Kingdom with the Scottish Government being the first to halt the use of trans-vaginal mesh in 2014[3]. However the incidence of mesh-related complications, and particularly mesh erosion, after LVMRs is low, especially when a biological mesh is used[4]. This was shown by Balla et al[4] in their review of literature where they demonstrated that the synthetic and the biological mesh-related erosion rates were 1.87% and 0.22%, respectively.

Furthermore, there is evidence that using biological mesh such as Permacol in LVMR results in significant improvement in function and quality of life outcomes, including improvement of urogynaecological symptoms[5]. In addition, latest results were comparable to synthetic mesh in terms of recurrence[5].

The aim of this study was to investigate the outcomes of LVMR using a biologic mesh in a district general hospital in an era where there is concern regarding the placement of pelvic mesh. We assessed the outcome of the procedure in relation to complications, bowel function and recurrences of symptoms following surgery.

This is a retrospective study of 86 consecutive patients that underwent LVMR from June 2012 to August 2018 in University Hospital of Wishaw. For 40 of them obstructive defecation was the main symptom, for 38 it was both obstructive defecation and faecal incontinence, 5 (5.8%) presented with pain and bleeding related to full thickness rectal prolapsed and 3 with mainly symptoms of faecal incontinence. All patients had a full history and physical examination, and a lower gastrointestinal endoscopic assessment. All, except those with obvious full thickness rectal prolapse, underwent a defecating proctogram, while 9 of them (10%) had anorectal physiology studies. Seven (0.08%) patients with not so clear symptoms and findings required an examination of the anorectum under general anaesthesia prior to the procedure. A detailed obstetric and pelvic surgery history was taken for women, and following formal development of Pelvic Floor multidisciplinary, all the patients were discussed on a monthly basis at the pelvic floor multidisciplinary team (Table 1).

| Patient characteristics | |

| Number of patients | 86 |

| Mean age in years | 57 yr (IQR: 47-70) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 82 |

| Male | 4 |

| Indication for surgery | |

| Rectal prolapse | 33 (4 male) |

| Obstructive Defeacation/Faecal Incontinence | 53 |

| Previous surgery for prolapse | 14 |

| Previous hysterectomy | |

| Yes | 24 |

| No | 58 |

| Male | 4 |

The functional outcomes for these patients were calculated using the Wexner scoring system for constipation and incontinence before and after surgery. All patients had a follow-up appointment in the clinic 3 mo after surgery and further follow-up 6-12 mo later. We also reviewed the notes on average 18.3 ± 4.2 mo after the procedure. Clinical outcomes of surgery and any complications resulting from surgery were recorded in the Pelvic Floor Society hosted national database.

At University Hospital Wishaw all LVMR procedures from June 2012 to August 2018 were performed by the same colorectal surgeon. After creating pneumoperitoneum and inserting the working ports (12 mm port on the right iliac fossa, 5 mm supra umbilical port and a 5 mm port in the right abdomen, the pelvic peritoneum at sacral promontory was opened using hook diathermy and continued distally and anteriorly down to the level of the levator muscles, while preserving the lateral ligaments and the hypogastric and sacral nerves. The biological porcine skin mesh that was used for all cases (permacol 4 × 18 cm long and 1 mm thick) was sutured as distally as possible onto the anterior rectal wall using interrupted seromuscular nonabsorbable sutures (2-0 Ethibond, Ethicon Endosurgery, Raritan, NJ, United States) and the upper part of the mesh was fixated to the sacral promontory using 4-5 spiral attachments (Pro-TackTM Fixation Device, Medtronic, Dublin, Ireland). Also, the gap between vagina and mesh was closed in women using 2.0 PDS (Figure 1).

The peritoneum was closed over the mesh with a continuous suture (V-lock 180, 15 cm). Perioperative care was conducted per the enhanced recovery after surgery protocol. A urinary catheter was inserted after the patient was anesthetised and was removed on the first post-operative day.

Pre-operative and post-operative Wexner score values for constipation and incontinence were inserted in tables. The median and interquartile range (IQR) values were calculated, and comparison and analysis between pre-operative and post-operative values were performed using the Wilcoxon signed rank test. Complication and recurrence rates were evaluated and analysed using the Kaplan-Meier method. A P value < 0.05 was considered as significant. Libreoffice Calc 6.2.8 was used for the calculations (The Document Foundation).

A total of 86 patients underwent LVMR from June 2012 to August 2018. Eighty-two (95%) were female and 4 (5%) were male with a median age of 57 years (IQR: 47-70). The median hospital stay was 1 d (IQR: 1-2). The first follow-up of the patients was at 3 mo, and the second one was 6-12 mo after surgery.

The pre-operative Wexner scores were calculated during the first visit to the clinic, usually 6-9 mo prior to surgery, while the post operative Wexner scores for constipation and incontinence were calculated on forms filled in during the consecutive follow-up appointment with the patient and in some cases over a telephone conversation with the patient by one of the surgical team members. Out of the 86 patients, pre-operative data were obtained for 86 patients, while post-operative Wexner score was obtained for 80 patients, since 6 of them did not return the forms. For these 80 patients the median post-operative Wexner score for constipation was 3 (IQR: 1-6), which was significantly improved compared to the median pre-operative score for constipation which was 14.5 (IQR: 10.5-18.5) (P < 0.01). Again, comparing the median pre-operative Wexner score for incontinence, which was 11 (IQR: 7-15), to the median post-operative score for faecal incontinence, which was 2 (IQR: 0-5), there was also a significant improvement demonstrated (P < 0.01) (Table 2).

| Mean Wexner scores | |||

| Pre-operative | Post-operative | P value | |

| Constipation | 14.5 (IQR: 10.5-18.5) | 3 (IQR: 1-6) | < 0.01 |

| Incontinence | 11 (IQR: 7-15) | 2 (IQR: 0-5) | < 0.01 |

All the procedures were completed laparoscopically, and there was no surgery related mortality recorded. No mesh related infection or erosion was recorded, although there was 1 case of diskitis that had to be treated with antibiotics after seen in the clinic for a follow-up. One of the patients developed an incarcerated femoral hernia post-surgery, which was seen intraoperatively but not repaired since the patient was not consented for that procedure, and it was repaired on day 2. Out of the 86 patients, 3 (3.4%) had issues with chronic pelvic pain after the procedure. Two of the patients complained of a foreign body sensation/irritation in rectum and were found to have a suture protruding through the rectum that was removed in clinic, which was followed by immediate relief of their symptoms. Out of the 86 patients, 4 (4.6%) of them came back with a recurrence of symptoms, 3 (2.3%) of which had a posterior prolapse recurrence and 2 of which eventually underwent a modified Delorme’s procedure.

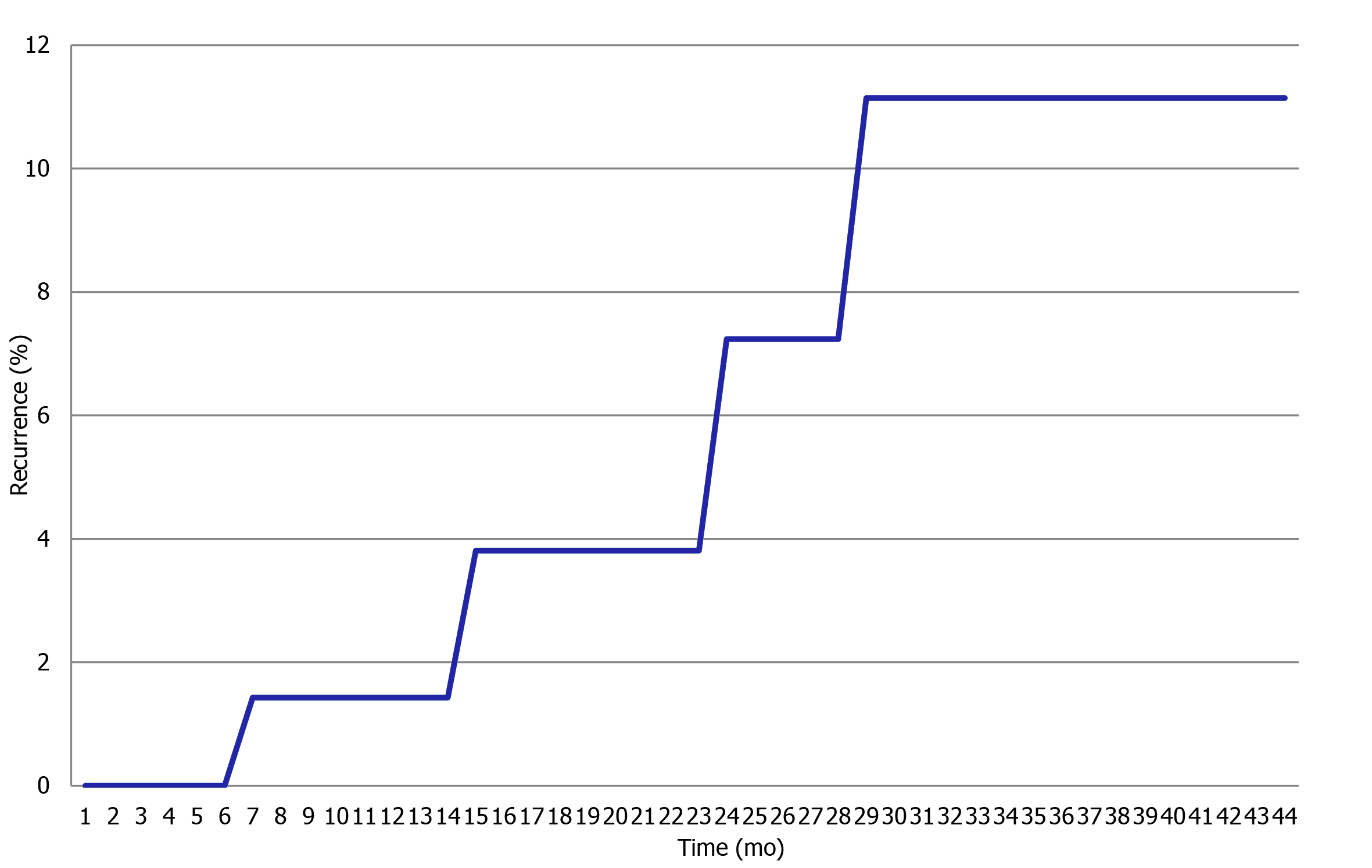

Overall recurrence at 12 mo was estimated with the Kaplan-Meier method as 1.4% (95%CI: 0.3%#4.0%), 7% (95%CI: 6.1%#15.5%) at 2 years and 11% (95%CI: 6.7%#16.8%) at 3 years (Figure 2).

Laparoscopic ventral mesh rectopexy is becoming one of the leading treatment options for the elective repair of rectal prolapse around the world[6,7]. Perineal procedures are still performed especially for elderly patients and those with associated significant comorbidity who are not candidates for transabdominal laparoscopic procedures[8,9]. However, there are recent studies that demonstrate that LVMRs would be safe for selected elderly patients as well[10]. In our series, there were 5 elderly patients over 80 that had a successful procedure with a good outcome.

When LVMRs are compared to resectional and posterior rectopexies, the functional results are better, especially since there is no interference with the sacral nerves and therefore fewer issues with slow transit constipation[11]. Other surgical procedures such as stapled transanal rectal resection can be used for rectal intussusception and obstructive defecation secondary to rectoceles as an alternative surgical approach to laparoscopic ventral mesh rectopexy[12]. However, this procedures has been associated with higher morbidity rates including pain, haemorrhage and sepsis[13].

Over the past years there has been a major concern over the use of mesh in pelvic surgery, but in our series of patients so far there were no mesh related complications, such as mesh erosion or infection. This is likely due to the consistent use of biological mesh in all of our cases, and our findings therefore come in agreement with previous studies’ findings that the mesh related complications are far less when using a biologic mesh instead of a synthetic one[4]. Although our directly obtained data of follow-up were for 1 year after surgery, the fact that there was only one colorectal surgeon that provides such surgery in Lanarkshire combined with the absence of re-referrals of previously operated patients for symptoms related to mesh complication, indirectly suggests that there was no mesh complication over a period of 5 years. Balla et al[4] have shown after reviewing the literature that using a biological mesh is a safer option than using a synthetic one, especially since the synthetic and the biological mesh-related erosion rates were 1.87% and 0.22%, respectively.

Although there was an initial concern that using biological mesh might be associated with higher recurrence rate, it has been demonstrated that there was no difference in recurrence when using a biological mesh compared to a synthetic one[11]. It has also been suggested that biological mesh should be preferred in patients with a high risk of fistula formation, such as those with diverticular disease, Crohn's disease, previous pelvic irradiation and steroid use[12]. Additionally, in another study, Mercer-Jones et al[13] suggested it could be prudent to use a biological mesh in young adolescents or women of child-bearing age regardless of the higher cost.

Complications were observed in the current study. Lumbosacral discitis near the site of mesh fixation to the sacral promontory was observed in 1 patient. This is a rare but serious complication with patients typically presenting 1-3 mo after the initial operation with severe lower back pain, fever and malaise[14]. In this case, magnetic resonance imaging confirmed the diagnosis, and broad spectrum antibiotics were given as they are the treatment of choice[14, 15]. Although an uncommon complication, it should always be considered for patients that present with lower back pain after an LVMR[14, 15]. Two patients presented with rectal symptoms of discharge and discomfort and were found to have ethibond suture erosion into their rectum. This is likely related to the suturing technique or the material itself, although there is no report of this complication in the literature so far[16]. In both patients, symptoms improved dramatically after transanal removal of sutures at outpatient/endoscopy room.

In our study, we had 4 patients that had a recurrence of their symptoms (4.6%). A systematic review of the literature by Samaranayake et al[17] has demonstrated that across various studies with median follow-up ranging from 3 to 106 mo the recurrence rates varied from 0%-15.4%. Our Kaplan Meier analysis revealed a 2 year recurrence rate of 7%, which can be compared to other studies like McLean et al[5] who demonstrated a recurrence rate of 9.74% (95%CI: 6.1%#15.5%) at 2 years.

It is evident that our study demonstrates a significant improvement of patients’ symptoms of obstructive defecation. The median post-operative Wexner score for constipation was 3 (IQR: 1-6) compared to the median pre-operative score which was 14.5 (IQR: 10.5-18.5), demonstrating a significant improvement (P < 0.01). These results are comparable to the results of Franceschilli et al[18] who demonstrated that the mean Wexner score for constipation improved from 18.4 ± 11.6 to 5.4 ± 4.1 (P = 0.04). Comparing the average pre-operative Wexner score for incontinence (11, IQR: 7-15) to the median post-operative score for incontinence (2, IQR: 0-5), there was also a significant improvement demonstrated (P < 0.01).

There was an overall improvement of the daily life activity for the majority of patients, which correlates with the results of other studies[4,17,18]. McLean et al[5] demonstrated patient satisfaction levels of 93% at 5 years, Consten et al[19] showed that both rates of faecal incontinence and obstructed defecation decreased significantly after LVR compared to the preoperative incidence.

In conclusion, our study adds more evidence to support that LVMR using biological mesh is a safe and effective procedure for the treatment of rectal prolapse and that it significantly improves bowel symptoms of obstructive defecation and faecal incontinence in patients with not only full thickness prolapse but also internal rectal prolapse and rectoceles[6,7,17,19]. In our study there were no mesh related complications, and this result correlates with the low biological mesh complication rate reported in other studies[4,13]. Our recurrence rates are in line with the ones reported in the literature[16], and although we acknowledge that the direct follow-up period was short, the absence of re-referral of those previously operated patients over the period of 5 years would indirectly suggest the safety of the mesh over longer periods. However, our continued effort is to follow this group of patients more directly and continue to assess formally their quality of life in the near future.

Laparoscopic ventral mesh rectopexy (LVMR) has over the past years become the preferred treatment for full thickness rectal prolapse, rectoceles, enteroceles and symptomatic rectal intussusception in many colorectal surgical centres around the world.

Over the last few years there have been concerns about the usage of meshes in pelvic surgery, especially since serious complications have been recorded in urogynaecology procedures.

To show that the incidence of mesh-related complications, and particularly mesh erosion, after LVMRs is low, especially when a biological mesh is used. We also wanted to investigate whether there is a significant improvement in function and quality of life outcomes.

Questionnaires for the calculation of Wexner scores for constipation and incontinence were completed by 86 patients who underwent LVMR with Permacol (Biological) mesh from 2012 to 2018 at University Hospital Wishaw. The patients were followed up in the clinic 12 mo after surgery. Statistical analysis of the result included the calculation of median and interquartile range (IQR) values and comparison and analysis between pre-operative and post-operative values. Complication and recurrence rates were evaluated and analysed using the Kaplan-Meier method.

The median Wexner scores for constipation pre-operatively and post-operatively were 14.5 (IQR 10.5-18.5) and 3 (IQR: 1-6), respectively, while the median Wexner score for faecal incontinence was 11 (IQR: 7-15) and 2 (IQR: 0-5), respectively (P < 0.01). There were 4 (4.6%) recurrences, 2 cases with erosion of a suture through the rectum and 1 patient that returned with diskitis. There were no mesh complications or mortalities.

In our results, it is demonstrated that LVMR using a biological mesh is both safe and effective for the treatment of rectal prolapse and that it fundamentally improves bowel symptoms of obstructive defecation and faecal incontinence in patients with internal rectal prolapse and symptomatic rectoceles.

Since we acknowledge that the direct follow-up period was short, we will continue our efforts to follow up our patients and formally assess their quality of life again in the near future.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: United Kingdom

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Hori T S-Editor: Wang LL L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Wang LL

| 1. | Faucheron JL, Trilling B, Girard E, Sage PY, Barbois S, Reche F. Anterior rectopexy for full-thickness rectal prolapse: technical and functional results. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:5049-5055. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Mäkelä-Kaikkonen J, Rautio T, Kairaluoma M, Carpelan-Holmström M, Kössi J, Rautio A, Ohtonen P, Mäkelä J. Does Ventral Rectopexy Improve Pelvic Floor Function in the Long Term? Dis Colon Rectum. 2018;61:230-238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Halt in use of transvaginal mesh. [cited 20 February 2021]. Available from: https://www.gov.scot/news/halt-in-use-of-transvaginal-mesh/. |

| 4. | Balla A, Quaresima S, Smolarek S, Shalaby M, Missori G, Sileri P. Synthetic Versus Biological Mesh-Related Erosion After Laparoscopic Ventral Mesh Rectopexy: A Systematic Review. Ann Coloproctol. 2017;33:46-51. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | McLean R, Kipling M, Musgrave E, Mercer-Jones M. Short- and long-term clinical and patient-reported outcomes following laparoscopic ventral mesh rectopexy using biological mesh for pelvic organ prolapse: a prospective cohort study of 224 consecutive patients. Colorectal Dis. 2018;20:424-436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Bachoo P, Brazzelli M, Grant A. Surgery for complete rectal prolapse in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;CD001758. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Tou S, Brown SR, Nelson RL. Surgery for complete (full-thickness) rectal prolapse in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;CD001758. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ahmad NZ, Stefan S, Adukia V, Naqvi SAH, Khan J. Laparoscopic Ventral Mesh Rectopexy: Functional Outcomes after Surgery. Surg J (N Y). 2018;4:e205-e211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Madiba TE, Baig MK, Wexner SD. Surgical management of rectal prolapse. Arch Surg. 2005;140:63-73. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 10. | Gultekin FA, Wong MT, Podevin J, Barussaud ML, Boutami M, Lehur PA, Meurette G. Safety of laparoscopic ventral rectopexy in the elderly: results from a nationwide database. Dis Colon Rectum. 2015;58:339-343. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 11. | Cadeddu F, Sileri P, Grande M, De Luca E, Franceschilli L, Milito G. Focus on abdominal rectopexy for full-thickness rectal prolapse: meta-analysis of literature. Tech Coloproctol. 2012;16:37-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Jones OM, Cunningham C, Lindsey I. The assessment and management of rectal prolapse, rectal intussusception, rectocoele, and enterocoele in adults. BMJ. 2011;342:c7099. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Mercer-Jones MA, Brown SR, Knowles CH, Williams AB. Position statement by the Pelvic Floor Society on behalf of the Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland on the use of mesh in ventral mesh rectopexy. Colorectal Dis. 2020;22:1429-1435. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Propst K, Tunitsky-Bitton E, Schimpf MO, Ridgeway B. Pyogenic spondylodiscitis associated with sacral colpopexy and rectopexy: report of two cases and evaluation of the literature. Int Urogynecol J. 2014;25:21-31. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Vujovic Z, Cuarana E, Campbell KL, Valentine N, Koch S, Ziyaie D. Lumbosacral discitis following laparoscopic ventral mesh rectopexy: a rare but potentially serious complication. Tech Coloproctol. 2015;19:263-265. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Hori T, Yasukawa D, Machimoto T, Kadokawa Y, Hata T, Ito T, Kato S, Aisu Y, Kimura Y, Takamatsu Y, Kitano T, Yoshimura T. Surgical options for full-thickness rectal prolapse: current status and institutional choice. Annals of Gastroenterology. 2018;31:188-197. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Samaranayake CB, Luo C, Plank AW, Merrie AE, Plank LD, Bissett IP. Systematic review on ventral rectopexy for rectal prolapse and intussusception. Colorectal Dis. 2010;12:504-512. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 164] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 18. | Franceschilli L, Varvaras D, Capuano I, Ciangola CI, Giorgi F, Boehm G, Gaspari AL, Sileri P. Laparoscopic ventral rectopexy using biologic mesh for the treatment of obstructed defaecation syndrome and/or faecal incontinence in patients with internal rectal prolapse: a critical appraisal of the first 100 cases. Tech Coloproctol. 2015;19:209-219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Consten EC, van Iersel JJ, Verheijen PM, Broeders IA, Wolthuis AM, D'Hoore A. Long-term Outcome After Laparoscopic Ventral Mesh Rectopexy: An Observational Study of 919 Consecutive Patients. Ann Surg. 2015;262:742-7; discussion 747. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 14.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |