Published online Jan 21, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i3.1024

Peer-review started: May 31, 2021

First decision: October 16, 2021

Revised: November 3, 2021

Accepted: December 22, 2021

Article in press: December 22, 2021

Published online: January 21, 2022

Processing time: 229 Days and 8 Hours

Othello syndrome (OS) is characterized by delusional beliefs concerning the infidelity of a spouse or sexual partner, which may lead to extreme behaviors. Impulse control disorders refer to behaviors involving repetitive, excessive, and compulsive activities driven by an intense desire. Both OS and impulse control disorders in Parkinson’s disease (PD) may be side effects of dopamine agonists. At present, there are only a few case reports and studies related to PD with concomitant OS and impulse control disorders.

We describe a 70-year-old male patient with PD, OS, and impulse control disorders, who presented with a six-month history of the delusional belief that his wife was having an affair with someone. He began to show an obvious increase in libido presenting as frequent masturbation. He had been diagnosed with PD ten years earlier and had no past psychiatric history. In his fourth year of PD, he engaged in binge eating, which lasted approximately one year. Both OS and hypersexuality were alleviated substantially after a reduction of his pramipexole dosage and a prescription of quetiapine.

Given its potential for severe consequences, OS should be identified early, especially in patients undergoing treatment with dopamine agonists.

Core Tip: Both Othello syndrome (OS) and impulse control disorders in Parkinson’s disease (PD) may be considered side effects of dopamine agonist therapy. These syndromes may have severe consequences; thus, when clinical features of either syndrome appear, the features of both syndromes should be investigated further. We report the case of a patient with PD, OS, hypersexuality, and binge eating. The syndrome was alleviated after a reduction of the patient’s pramipexole dosage and the addition of quetiapine.

- Citation: Xu T, Li ZS, Fang W, Cao LX, Zhao GH. Concomitant Othello syndrome and impulse control disorders in a patient with Parkinson’s disease: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(3): 1024-1031

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i3/1024.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i3.1024

Othello syndrome (OS), also defined as delusional jealousy, is characterized by paranoid delusional beliefs concerning the infidelity of a partner, which may lead to extreme behaviors[1]. This syndrome has been observed in psychiatric patients and neurological patients, such as those with stroke[2], dementia, and Parkinson’s disease (PD)[3]. In a retrospective study of 105 patients with OS at the Mayo Clinic[3], 69.5% had neurological disorders while 30.5% had psychiatric disorders; voxel-based morphometry showed grey matter loss was greater in the patients with neurodegenerative diseases and OS, especially the dorsolateral frontal lobes. Hence, OS is an uncommon but potentially dangerous syndrome in patients with PD.

Impulse control disorders (ICDs) refer to behaviors involving repetitive, excessive, and compulsive activities driven by intense desire[4]. These behaviors include pathological gambling, hypersexuality, compulsive shopping, and binge eating. As ICDs in PD have received increasing attention, the clinical symptom spectrum has gradually expanded to include dopamine dysregulation syndrome, hobbyism, and punding[5]. Both OS and ICDs in PD may be considered as side effects of dopamine agonists[6]. At present, there are only a few case reports and studies related to PD patients with concomitant OS and ICDs. We present the case of a male patient diagnosed with PD who developed OS and ICDs, and report the results of our review of the related literature.

A 70-year-old right-handed man, who showed the first signs of PD at 60 years of age, was admitted to our hospital for behavioral alterations. He presented with a six-month history of a delusional belief that his wife was having an affair with someone. At the same time, he began to show an obvious increase in libido presenting as frequent masturbation.

The patient noticed he had a right-hand tremor ten years ago and then developed akinesia and rigidity. He was diagnosed with PD by a neurologist approximately one year later. Following treatment with levodopa-benserazide (200-50 mg/d), he initially showed significant improvement. His symptoms then progressed to difficulty turning during a walk, constipation, olfactory dysfunction, and vivid anxiety-provoking dreams. Seven years ago, the patient engaged in binge eating with a significant increase in food consumption, eating 3-4 times at night, and the symptoms lasted approximately one year. Six years ago, pramipexole (0.75 mg/d) and selegiline (1 mg/d) were prescribed. His pramipexole dosage was titrated up to 1.5 mg/d. In the past year, his memory has declined, especially his recent memory. About six months ago, he began to accuse his wife of having an affair with someone, although he could not provide any evidence of infidelity. The delusional belief was confirmed by his wife and two children. At the same time, he began to show an obvious increase in libido presenting as frequent masturbation. Three months before his current admission to the hospital, he developed visual hallucinations of seeing ghosts in the window. This visual hallucination was so vivid that he often asked family members to exorcise the ghosts.

The patient was otherwise healthy. He denied a history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, prior cerebrovascular disease, or other neurological complications. He had no past psychiatric history.

The patient had a college diploma and was retired from the Municipal People's Procuratorate. He denied a past history of drug or alcohol abuse, smoking, and sexual promiscuity. One of his five siblings had PD, but there was no family history of psychiatric illness. The patient is married and has two children who are living independently.

The patient’s general examination was unremarkable. The neurologic examination revealed a masked-like facial expression. The motor examination revealed moderate bradykinesia and rigidity of all four limbs. Mild resting tremor was present in the patient’s right upper extremity, and he exhibited difficulty in the initiation of walking and turning. A reduced arm swing was observed when walking, and his performance on the pull-back test was negative. No other positive neurological signs were found. The patient’s scores on the rating scales were as follows: 29 on Part III of the Unified PD Rating Scale, stage II on the Hoehn and Yahr scale, 9/30 on the Mini-Mental State Examination, 13/30 on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment Scale, 11 on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, and 11 on the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale.

The following laboratory tests were within normal limits: blood cell count, liver and renal function, thyroid function, electrolytes, vitamin B12, folate, syphilis, and tumor markers.

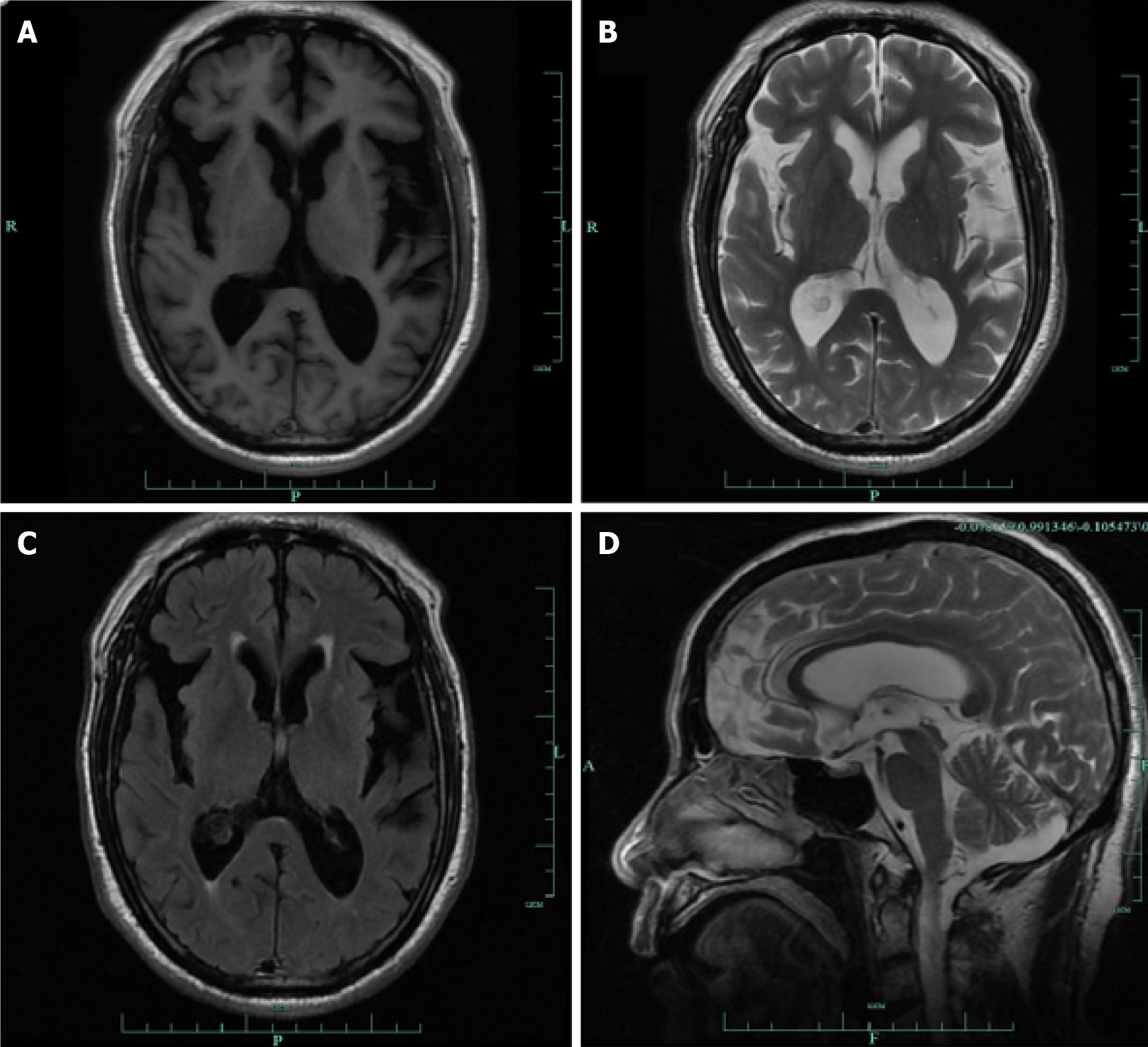

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed mild bilateral frontotemporal atrophy (Figure 1). The T1, T2 and FLAIR sequence showed temporal atrophy, with broadening of the posterior horn of the lateral ventricle (Figure 1A-C); and the magnetic resonance sagittal view showed mild frontal lobe atrophy (Figure 1D).

PD with OS, ICDs, and dementia were diagnosed based on the patient’s symptoms and findings from the neurologic examination.

The patient’s dose of pramipexole was reduced to 50% of the current dosage, and quetiapine 25 mg/d was prescribed. Entacapone was added to alleviate the worsening of his motor symptoms.

The patient’s symptoms showed marked improvement at the follow-up visit two months later, the delusion concerning his wife’s infidelity subsided and his motor syndrome remained stable.

Although PD is a common degenerative neurological disorder with typical motor symptoms, its non-motor symptoms have received increasing attention. The most recent update on treatments for non-motor symptoms of PD authored by the Evidence-Based Medicine Committee of the International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society includes ICDs[7], whereas OS, which has a relatively lower prevalence, is reported less often. In a cross-sectional study of ICDs and OS[6] in 1063 PD patients, 81 of them presented with ICDs (7.61%) and 23 presented with OS (2.16%), while 9 patients presented with both OS and ICDs. A diagnosis of OS is infrequent in PD patients, but its occurrence may have severe consequences. Here, we report the case of a 70-year-old male PD patient with concomitant OS and ICDs, who had a good response to a reduction of his pramipexole dosage and the addition of quetiapine to his medication regimen.

OS in PD is reported infrequently; thus, we conducted a search of the English-language research literature from 2000-2021 in the MEDLINE database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov), using the following keywords: Othello syndrome, delusional jealousy, delusions, jealousy and PD. The search yielded one case report[8], two case series[9,10], and four studies[6,11-13], which we reviewed in addition to our case report. The characteristics of a total of 28 patients who had PD with concomitant OS and ICDs are presented in Table 1.

| Ref. | Patient | Sex | Age at PD onset | Age at OS onset | PD duration at OS onset | ICDs | Dopamine agonist | Visual hall-ucinations | Psychiatry history | Neuroimaging | Dementia | Measures undertaken |

| Poletti et al[6] | Patient 1 | M | 45 | 60 | 15 | PG + HS + BE | Pramipexole | Yes | N/A | N/A | No | N/A |

| Poletti et al[6] | Patient 2 | M | 50 | 62 | 12 | HS + PG + DDS | Ropinirole | Yes | N/A | N/A | No | N/A |

| Poletti et al[6] | Patient 3 | M | 67 | 76 | 9 | HS | Pramipexole | Yes | N/A | N/A | No | N/A |

| Poletti et al[6] | Patient 4 | M | 42 | 52 | 10 | HS | Ropinirole | No | N/A | N/A | No | N/A |

| Poletti et al[6] | Patient 5 | M | 34 | 40 | 6 | HS + PG | Pramipexole | No | N/A | N/A | No | N/A |

| Poletti et al[6] | Patient 6 | M | 48 | 58 | 10 | HS | Ropinirole | Yes | N/A | N/A | No | N/A |

| Poletti et al[6] | Patient 7 | M | 61 | 72 | 11 | HS | Pramipexole | Yes | N/A | N/A | No | N/A |

| Poletti et al[6] | Patient 8 | M | 57 | 65 | 8 | PG + punding + HS | Ropinirole | Yes | N/A | N/A | No | N/A |

| Poletti et al[6] | Patient 9 | M | 47 | 52 | 5 | HS + PG | Ropinirole | No | N/A | N/A | No | N/A |

| Cannas et al[8] | Patient 10 | M | 44 | 46 | 2 | HS | Pergolide | No | Anxiety, depression | N/A | No | Reduced pergolide, added quetiapine |

| Cannas et al[9] | Patient 11 | M | 44 | 49 | 5 | HS | Pergolide | No | N/A | Normal | No | Stopped pergolide, added quentiape |

| Adam et al[10] | Patient 12 | M | 38 | 39 | 1 | HS + CS | Cabergoline | N/A | Hypomania | N/A | N/A | Stopped cabergoline, STN-DBS |

| Adam et al[10] | Patient 13 | M | 32 | 34 | 2 | PG + DDS | Pergolide | N/A | No | N/A | N/A | Stopped pergolide, STN-DBS |

| Graff-Radford et al[11] | Patient 14 | M | 49 | 58 | 9 | HS | Pramipexole | N/A | No | N/A | N/A | Stopped pramipexole |

| Graff-Radford et al[11] | Patient 15 | M | 39 | 42 | 3 | HS + PG | Pramipexole | N/A | No | Normal | N/A | Stopped pramipexole |

| Graff-Radford et al[11] | Patient 16 | F | 53 | 64 | 11 | CS | Pramipexole | N/A | Anxiety | Normal CT | N/A | Stopped prmipexole |

| Graff-Radford et al[11] | Patient 17 | M | 43 | 49 | 6 | HS | Ropinirole | N/A | Depression | Normal | N/A | Stopped ropinirole |

| Graff-Radford et al[11] | Patient 18 | M | 50 | 56 | 6 | HS + PG | Pramipexole | N/A | No | N/A | N/A | Stopped prmipexole |

| Graff-Radford et al[11] | Patient 19 | F | 43 | 56 | 13 | HS | Pramipexole | N/A | Anxiety | Old right basal ganglia infarct | N/A | Reduced prmipexole |

| Graff-Radford et al[11] | Patient 20 | M | 49 | 51 | 2 | HS + CS | Ropinirole | N/A | Anxiety | Normal | N/A | Stopped ropinirole |

| Foley et al[12] | Patient 21 | M | 51 | NA | NA | HS | Ropinirole | Yes | N/A | mild left fronto-temporal atrophy | N/A | Reduced ropinirole |

| Foley et al[12] | Patient 22 | F | 47 | NA | NA | CS | Ropinirole | Yes | N/A | Normal | N/A | Stopped ropinirole |

| Foley et al[12] | Patient 23 | M | 36 | NA | NA | HS + CS + PG | Ropinirole | N/A | N/A | Normal | N/A | Reduced ropinirole |

| Foley et al[12] | Patient 24 | F | 50 | NA | NA | CS | Ropinirole | Yes | N/A | Normal | N/A | N/A |

| Foley et al[12] | Patient 25 | M | 60 | NA | NA | HS | Rotigotine | Yes | N/A | Normal | N/A | N/A |

| El Otmani et al[13] | Patient 26 | M | 37 | 40 | 3 | HS | Pramipexole | N/A | N/A | N/A | No | Reduced pramipexole, added clozaping |

| El Otmani et al[13] | Patient 27 | M | 40 | 44 | 4 | Punding | Piribedil | N/A | N/A | N/A | No | Reduced piribedil, added quetiapine |

| This study | Patient 28 | M | 60 | 69 | 9 | BE+HS | Pramipexole | Yes | No | Mild bilateral frnto-remporal atrophy | Yes | Reduced pramipexole, added quetiapine |

Concomitant OS and ICDs were more common in males (24 patients) and in middle-aged patients. In a retrospective case series study in the Mayo Clinic, 61.9% (65/105) of the patients were male[3]. Similar results were found in studies on PD with ICDs. A prospective multi-center study found that PD patients with ICDs were more likely to develop in males, younger patients, and patients with an earlier onset of PD[14]. The average age of PD onset was 47.00 ± 8.63 years, and only two patients who developed OS were older than 70 years. The mean duration of PD at OS onset was 7.04 ± 3.99 years, which was similar to the previous study at the Mayo Clinic[11].

Among the ICDs in our review, hypersexuality (HS) was most prevalent (23/28 patients). Pathological gambling was observed in 9 patients, compulsive shopping in 6 patients, binge eating in 2 patients, punding in 2 patients, and dopamine dysregulation syndrome in 2 patients. HS is characterized by excessive sexual thoughts or behaviors or an atypical change from baseline behavior, such as an inappropriate or excessive sexual desire for the partner, compulsive masturbation, or the development of paraphilias[5]. A functional MRI study compared a group of 12 PD patients with HS with a control group with PD without HS or other ICDs[15]. The results showed an increase in sexual desire in PD patients with HS after exposure to sexual cues; and the increased sexual desire correlated with enhanced activation in the ventral striatum, cingulate cortex, and orbitofrontal cortex. The pathophysiology of OS remains unclear. A previous study showed that OS is associated with the dopaminergic frontostriatal circuits, ventromedial prefrontal cortex, and insula[16]. Overall, both HS and OS were found to be associated with hyperdopaminergic behaviors[13].

Previous studies have shown a relationship between dopamine agonists and OS[9,17-19]. One of these studies, a cross-sectional prevalence study of 805 consecutive PD patients, revealed a significant association between dopamine agonists and OS (odds ratio, 18.1)[17]. Other dopaminergic medications have been reported to have an association with OS, such as amantadine[20], levodopa[9], and selegiline[21]. In our review, all 28 patients were using dopamine agonists at the onset of OS, consistent with the results of previous studies. Pramipexole and ropinirole were used most frequently by 11 patients, pergolide was used by 3 patients, and cabergoline, piribedil, and rotigotine were each used by 1 patient. The duration of treatment with dopamine agonists at the onset of OS varied from a few months to several years under a stable dose. For example, one of the patients[12] developed OS one month after receiving ropinirole treatment, whereas our patient exhibited characteristics of OS more than five years after receiving pramipexole. In early PD, the dopamine depletion is greatest in the ventrolateral tier of the substantia nigra pars compacta, which projects primarily into the dorsal striatum. Thus, the functioning of the dorsolateral frontostriatal circuit (linking the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and the dorsal striatum), which mediates executive functions, can be restored by dopaminergic medication[22]. However, dopaminergic medication may cause overdosing of the relatively intact orbital frontostriatal circuit (linking the orbitofrontal cortex and the ventral striatum), which mediates reward processing. Dopamine agonists may induce non-physiological tonic dopaminergic stimulation of the orbital frontostriatal circuit, which can lead to an evaluation of the stimulus as a positive reward, thereby inducing an aberrant salient relationship with a loved one[16], and consequently, a greater fear of losing the relationship, resulting in OS. Furthermore, excessive motivation to achieve sexual goals may lead to HS.

The concurrent development of OS and ICDs in our review was more common among patients without dementia and with moderate motor deterioration. Two age peaks in the incidence of PD with OS have been reported: The first peak is in young patients with mild motor impairment and a negligible decline in cognition and the second peak occurs in advanced PD patients with severe motor and cognitive decline[9]. We believe that OS in our patient was associated with both cognitive impairment and the use of dopamine agonists. In addition to having OS and ICDs, 11 of 16 patients in our review had visual hallucinations, and 6 of 11 patients had a psychiatric history; however, the true prevalence could be much higher. The MRI of most of the patients showed normal findings; only one patient’s MRI showed an old infarct of the right basal ganglia, and another patient’s MRI showed mild left frontotemporal atrophy. In our case, the patient showed mild bilateral frontotemporal atrophy, consistent with dementia.

OS may lead to marital discord and breakdown or have other negative effects. The treatment of OS in patients with PD includes the withdrawal or dosage reduction of dopamine agonists, plus a prescription for atypical antipsychotics at low doses. In 10 of 17 patients in our review, the syndrome was relieved or eliminated with a dosage reduction or withdrawal of the dopamine agonists. Atypical neuroleptics had to be added to 5 patients’ prescriptions: Clozapine for 1 patient and quetiapine for 4 patients. In our case report, it was necessary to use an antipsychotic (quetiapine), which was tolerated quite well. Improvement in our patient’s symptoms was progressive, although slow and gradual. In a case series of 3 young PD patients with OS receiving dopamine agonists, the OS resolved with the withdrawal of the drug and subsequent treatment with bilateral subthalamic nucleus deep brain stimulation (STN DBS)[11]. In another case report, psychotic symptoms in the form of OS appeared after undergoing bilateral STN DBS, and a gradual resolution was achieved by adding a low dosage of quetiapine[23].

Both OS and ICDs in PD may be side effects of dopamine agonist therapy. There is a frequent association between OS and ICDs; thus, when the features of either syndrome appear, the features of the other syndrome should be investigated. Clinicians should be aware of OS in patients with PD so they can identify it early, especially in patients treated with dopamine agonists, to help them avoid the devastating psychosocial consequences of this syndrome. PD patients may consider them unrelated to dopamine replacement therapies and even conceal the syndrome to their physician, resulting in challenging and late diagnoses. Patients and their partners should be warned about this uncommon but consequential syndrome. Withdrawal or reduction of dopamine agonists, plus prescriptions of atypical antipsychotics, can usually alleviate symptoms of the syndrome.

We are grateful to the patient for giving us his permission to submit this paper for publication.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Neurosciences

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Kashyap R S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: Webster JR P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Camicioli R. Othello syndrome-at the interface of neurology and psychiatry. Nat Rev Neurol. 2011;7:477-478. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ortigue S, Bianchi-Demicheli F. Intention, false beliefs, and delusional jealousy: insights into the right hemisphere from neurological patients and neuroimaging studies. Med Sci Monit. 2011;17:RA1-R11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Graff-Radford J, Whitwell JL, Geda YE, Josephs KA. Clinical and imaging features of Othello's syndrome. Eur J Neurol. 2012;19:38-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Weintraub D, David AS, Evans AH, Grant JE, Stacy M. Clinical spectrum of impulse control disorders in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2015;30:121-127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 219] [Cited by in RCA: 237] [Article Influence: 21.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Voon V, Fox SH. Medication-related impulse control and repetitive behaviors in Parkinson disease. Arch Neurol. 2007;64:1089-1096. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 283] [Cited by in RCA: 268] [Article Influence: 14.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Poletti M, Lucetti C, Baldacci F, Del Dotto P, Bonuccelli U. Concomitant development of hypersexuality and delusional jealousy in patients with Parkinson's disease: a case series. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2014;20:1290-1292. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Seppi K, Ray Chaudhuri K, Coelho M, Fox SH, Katzenschlager R, Perez Lloret S, Weintraub D, Sampaio C; the collaborators of the Parkinson's Disease Update on Non-Motor Symptoms Study Group on behalf of the Movement Disorders Society Evidence-Based Medicine Committee. Update on treatments for nonmotor symptoms of Parkinson's disease-an evidence-based medicine review. Mov Disord. 2019;34:180-198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 652] [Cited by in RCA: 629] [Article Influence: 104.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Cannas A, Solla P, Floris G, Tacconi P, Loi D, Marcia E, Marrosu MG. Hypersexual behaviour, frotteurism and delusional jealousy in a young parkinsonian patient during dopaminergic therapy with pergolide: A rare case of iatrogenic paraphilia. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2006;30:1539-1541. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Cannas A, Solla P, Floris G, Tacconi P, Marrosu F, Marrosu MG. Othello syndrome in Parkinson disease patients without dementia. Neurologist. 2009;15:34-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Adam RJ, McLeod R, Ha AD, Colebatch JG, Menzies G, de Moore G, Mahant N, Fung VSC. Resolution of Othello Syndrome After Subthalamic Nucleus Deep Brain Stimulation in 3 Patients with Parkinson's Disease. Mov Disord Clin Pract. 2014;1:357-360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Graff-Radford J, Ahlskog JE, Bower JH, Josephs KA. Dopamine agonists and Othello's syndrome. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2010;16:680-682. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Foley JA, Warner TT, Cipolotti L. The neuropsychological profile of Othello syndrome in Parkinson's disease. Cortex. 2017;96:158-160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | El Otmani H, Sabiry S, Bellakhdar S, El Moutawakil B, Abdoh Rafai M. Othello syndrome in Parkinson's disease: A diagnostic emergency of an underestimated condition. Rev Neurol (Paris). 2021;177:690-693. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Antonini A, Barone P, Bonuccelli U, Annoni K, Asgharnejad M, Stanzione P. ICARUS study: prevalence and clinical features of impulse control disorders in Parkinson's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2017;88:317-324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Politis M, Loane C, Wu K, O'Sullivan SS, Woodhead Z, Kiferle L, Lawrence AD, Lees AJ, Piccini P. Neural response to visual sexual cues in dopamine treatment-linked hypersexuality in Parkinson's disease. Brain. 2013;136:400-411. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Marazziti D, Poletti M, Dell'Osso L, Baroni S, Bonuccelli U. Prefrontal cortex, dopamine, and jealousy endophenotype. CNS Spectr. 2013;18:6-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Poletti M, Perugi G, Logi C, Romano A, Del Dotto P, Ceravolo R, Rossi G, Pepe P, Dell'Osso L, Bonuccelli U. Dopamine agonists and delusional jealousy in Parkinson's disease: a cross-sectional prevalence study. Mov Disord. 2012;27:1679-1682. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kataoka H, Sugie K. Delusional Jealousy (Othello Syndrome) in 67 Patients with Parkinson's Disease. Front Neurol. 2018;9:129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Georgiev D, Danieli A, Ocepek L, Novak D, Zupancic-Kriznar N, Trost M, Pirtosek Z. Othello syndrome in patients with Parkinson's disease. Psychiatr Danub. 2010;22:94-98. [PubMed] |

| 20. | McNamara P, Durso R. Reversible pathologic jealousy (Othello syndrome) associated with amantadine. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 1991;4:157-159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Kataoka H, Kiriyama T, Eura N, Sawa N, Ueno S. Othello syndrome and chronic dopaminergic treatment in patients with Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2014;20:337-339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Poletti M, Bonuccelli U. Orbital and ventromedial prefrontal cortex functioning in Parkinson's disease: neuropsychological evidence. Brain Cogn. 2012;79:23-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Antosik-Wójcińska AZ, Święcicki Ł, Bieńkowski P, Mandat T, Sołtan E. Othello syndrome after STN DBS - psychiatric side-effects of DBS and methods of dealing with them. Psychiatr Pol. 2016;50:323-327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |