Published online Oct 6, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i28.10317

Peer-review started: May 31, 2022

First decision: June 8, 2022

Revised: June 23, 2022

Accepted: August 16, 2022

Article in press: August 16, 2022

Published online: October 6, 2022

Processing time: 119 Days and 5.5 Hours

Malignant peritoneal mesothelioma (MPM) is an extremely rare tumor with nonspecific clinical manifestations, which is extremely difficult to diagnose. Herein, we reported a case of MPM in the abdominal cavity with massive short-term ascites as the first symptom.

A 65-year-old woman presented to the hospital with abdominal pain, distention, and shortness of breath that persisted for 15 d. The serum CA-125 level was 1075 U/mL. The abdominal computed tomography showed massive ascites and no obvious tumor lesions. The pathological examination of the ascitic fluid showed numerous heterotypic cells with some papillary structures. The immunohistochemistry and fluorescence in situ hybridization showed the deletion of CDX2 (-), WT-1 (-), Ki-67 (about 10% +), CEA (-), Glut-1 (+++), desmin (-), PD-L1 (-), and CDKN2A (P16). The final diagnosis was MPM. The patient refused tumor cytoreductive surgery and received two cycles of cisplatin plus pemetrexed bidirectional chemotherapy. In the second cycle, she received an additional cycle of hyper

In case of massive unexplained ascites, the possibility of MPM should not be excluded to avoid misdiagnosis and delay in treatment.

Core Tip: Malignant peritoneal mesothelioma (MPM) is an extremely rare tumor with nonspecific clinical manifestations, which is extremely difficult to diagnose. Herein, we reported a case with massive ascites as the first symptom. The patient was diagnosed with MPM based on a combination of histological, immune, and imaging findings. The patient refused tumor cytoreductive surgery and then received bidirectional chemotherapy, hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy, and immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy. Unfortunately, she died of disease progression two months after diagnosis. This case report aims to provide clinical evidence for the diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of rare MPM.

- Citation: Huang X, Hong Y, Xie SY, Liao HL, Huang HM, Liu JH, Long WJ. Malignant peritoneal mesothelioma with massive ascites as the first symptom: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(28): 10317-10325

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i28/10317.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i28.10317

Mesothelioma is a rare malignancy of serosal membranes. It commonly appears in the visceral pleura but may also be seen in the peritoneum[1]. Patients with malignant peritoneal mesothelioma (MPM) may have different symptoms, including abdominal distention, abdominal pain, early satiety, weight loss, nausea, new hernias, unexplained fever, night sweats, and so forth[2,3]. In addition, acute abdominal symptoms due to malignant intestinal obstruction or perforation have also been reported[4]. At present, there is no specific diagnosis for abdominal mesothelioma[5].

Herein, we reported a case of MPM in the abdominal cavity with massive short-term ascites as the first symptom. The patient was diagnosed by the pathological examination of ascites and exfoliated cells and genetic testing.

A 65-year-old female patient sought medical attention for abdominal distention and shortness of breath that persisted for 15 d.

The aforementioned symptoms appeared half a month ago with no apparent cause, and the patient felt as if her symptoms were worsening.

She had a history of high blood pressure and type 2 diabetes but no history of asbestos exposure.

The patient denied any family history of malignant tumors.

On admission to the hospital, she had a distended abdomen, with an abdominal circumference of 111 cm, slight tension in the abdominal muscles, mild tenderness, and mobile dullness. She reported a weight gain of 5 kg in 1 mo.

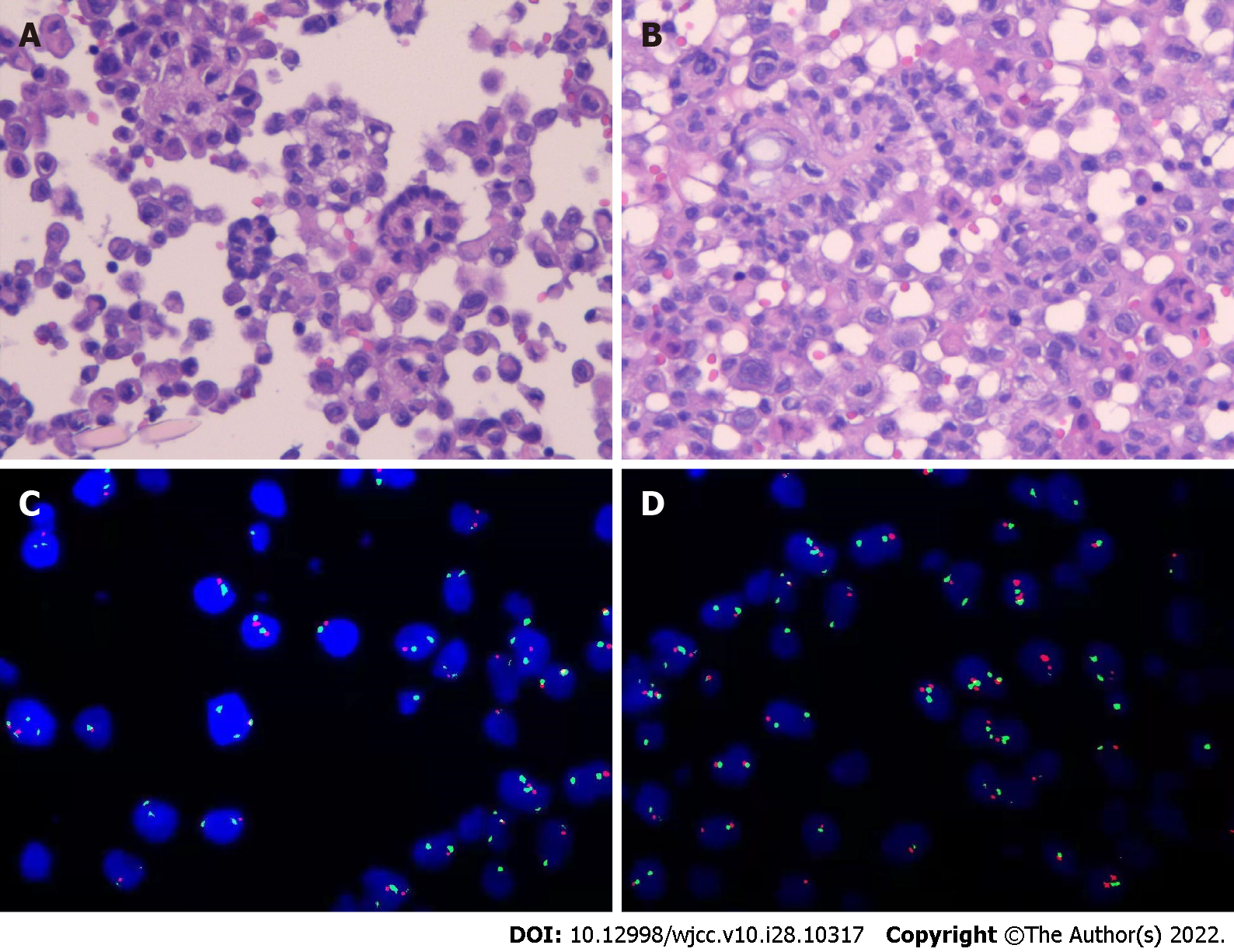

The findings of blood tests and routine examination of ascites are shown in Table 1. After collection, ascitic fluid was sent for pathological examination and immunohistochemistry. The final report of liquid-based cell preparation and cell-block hematoxylin and eosin (HE)-stained section indicated numerous atypical cells, some of which had papillary structures. The immunohistochemical (IHC) markers were as follows: CK (+), CK20 (-), Villin (-), CDX2 (-), CR (+), WT-1 (-), SATB-2 (scattered +), Ki-67 (about 10% +), TTF-1 (-), CEA (-), Pax-8 (-), P16 (individual +), M-mell (-), and Glut-1 (+++), and desmin (-). fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) detected CDKN2A (P16) gene deletion and PD-L1 (-) (Figure 1).

| Specimen | Item | First diagnosis (November 8) | Before the first chemotherapy (November 27) | After the first chemotherapy (December 9) | Before the first immunotherapy (December 13) | After the first immunotherapy (December 26) |

| Blood | CEA (ng/mL) | 1.18 | 1.38 | |||

| PLT (E+9/L) | 598 | 527 | 235 | 312 | 290 | |

| CA125 (U/mL) | 1075 | 395.2 | 314.7 | 354.6 | ||

| CA199 (U/mL) | 23.77 | - | 45.47 | 38.57 | ||

| HE4 (pmol/L) | 235.5 | - | - | 207.6 | ||

| ALB (g/L) | 34.3 | 36.1 | 33.7 | 27.2 | 30.7 | |

| T-SPOT | Negative | |||||

| Ascites | TP (g/L) | 50.4 | - | 26.7 | ||

| ADA (U/L) | 11 | - | 7 | |||

| Color | Yellow | - | Yellow | |||

| RBC (E+6/L) | 5000 | - | 1000 | |||

| WBC (E+6/L) | 2149 | - | 209 | |||

| CEA (ng/mL) | 0.73 |

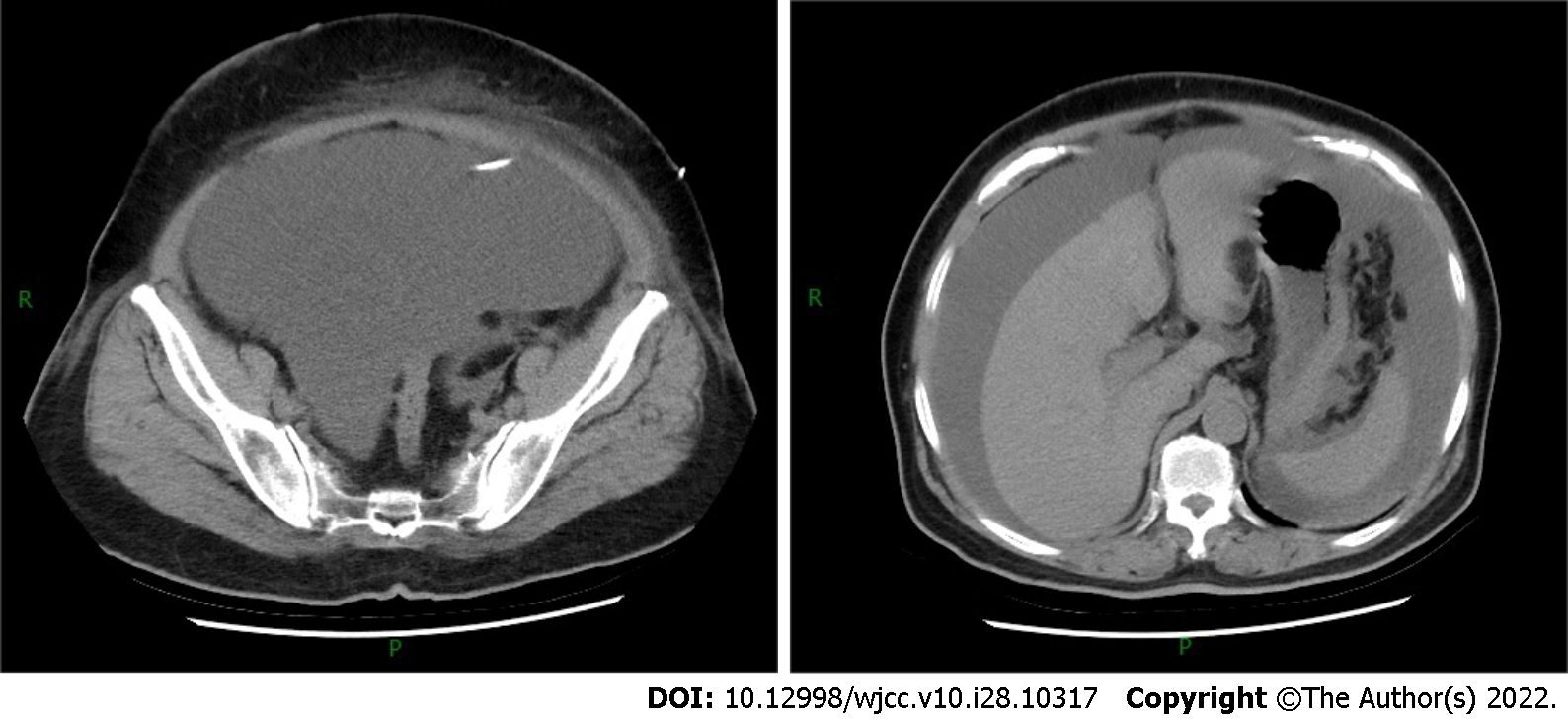

The contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) showed a large volume of ascites in the abdominal cavity, but no abdominal wall thickening or intra-abdominal soft-tissue shadow was observed (Figure 2). However, subsequent pelvic enhancement magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed mild peritoneal thickening (Figure 3).

Cases of MPM are rare, and their diagnosis is difficult. A pathological analysis indicted that ascetic fluid contains numerous proliferating cells with papillary structure formation and a few scattered atypical proliferating cells with SATB2 positivity. However, the results could not distinguish between epithelial-derived tumors and mesothelial-derived lesions. Thus, the recommendations were as follows: (1) Perform immunohistochemistry for BerEP4, CDX2, BAP1, EMA, SATB2, and P53 to assist in the diagnosis; and (2) Provide a comprehensive assessment of the detailed clinical picture (any history of gastrointestinal disease, any thickening of the pleura and peritoneum, etc.). However, the patient and her family refused further immunohistochemistry and laparoscopy.

The patient was diagnosed with MPM based on a combination of cytological, immune, and imaging tests.

The patient refused cytoreductive surgery (CRS) and only received two cycles of cisplatin plus pemetrexed bidirectional chemotherapy. She received an additional cycle of hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) and immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy in the second cycle of chemotherapy because of massive recalcitrant ascites.

The patient was scheduled to return for the third course of chemotherapy on January 13, 2022, but she passed away at home on January 12, 2022, due to disease progression.

MPM is a rare tumor that originates from mesothelioma cells on the surface of the peritoneum. The incidence of MPM in the population is about 1-2/100 million. Peritoneal mesothelioma is more common in women than pleural mesothelioma, and its association with asbestos exposure is weak. It often manifests as nonspecific symptoms such as abdominal pain, bloating, ascites, abdominal mass, gastrointestinal symptoms, and so forth. Therefore, MPM may be easily confused with peritonitis and peritoneal neoplastic lesions, such as tuberculous peritonitis, mesenteric lipid membrane inflammation, peritoneal pseudomyxoma, peritoneal metastasis, lymphoma, primary peritoneal serous carcinoma, mesenteric fibromatosis, etc.[5]. As observed in our patient, thrombocytosis was previously reported in some patients with malignant abdominal mesothelioma, but the specific pathogenesis is unclear[6].

No uniform criteria exist for diagnosing MPM. We propose a combination of clinical manifestations, imaging, and pathological features. The patient in this case presented with complaints of massive ascites and abdominal distention, which are common but nonspecific presentations of MPM.

CT is currently recommended as the first-choice examination. In intravenous contrast-enhanced CT images, soft-tissue shadows with irregular margins and large omental nodules or peritoneal thickening are often seen[5,7]. No solid tumor signs were seen on the mesentery, omentum, and peritoneum in this patient. However, a large amount of ascites and fatty edema of the abdominal wall were observed. The pelvic enhancement MRI showed mild peritoneal thickening, and the left lower abdominal wall subcutaneous fascia was in the shape of a mass with segmentation shadows. The enhancement scan was not uniformly enhanced, and the adjacent abdominal muscle was swollen. Because of the aggressive nature of MPM, the possibility of peritoneal lesions combined with abdominal wall infiltration could not be excluded. Notably, a slightly thickened pleura was seen bilaterally on enhanced CT images, but no pleural effusion and mediastinal lymph node enlargement were found. The patient had no respiratory symptoms such as dyspnea, chest pain, cough, and expectoration and lacked the patho

Confirming mesothelioma diagnosis requires histopathologic analysis, with the fine-needle aspiration of biopsies and laparoscopy being the common means of performing tests. The histological analysis can identify the histological subtype, grade, and degree of infiltration of mesothelioma. However, our patient refused tumor CRS.

Diagnostic paracentesis is the primary means of obtaining ascites for evaluation, and some epithelioid carcinomas can release malignant cells into the ascites. Given the large volume of ascites, we performed the cytological examination of exfoliated cells by examining the ascitic fluid to distinguish benign from malignant mesothelial lesions. The cytological diagnosis included HE staining and IHC staining. A large number of proliferating heterogeneous cells were seen in HE-stained sections of ascites and exfoliated cell blocks, which were suspected to be malignant tumor cells. However, a morphological overlap existed between the atypical reactive mesothelial hyperplasia and malignant mesothelioma. Hence, further immunochemical staining was performed to clarify the diagnosis and origin of the tumor. The IHC technique improved the reliability of pure cytology diagnosis.

Since most of the markers are not 100% specific for different types of tumors, the International Mesothelioma Interest Group recommends that the detection of tumor markers should include at least two mesothelioma markers in addition to pan-cytokeratin. Calretinin (CR), cytokeratin 5/6, WT-1, and podoplanin are the best positive mesothelioma markers in identifying tumor cell origin, whereas claudin 4, MOC31, BER-EP4, CEA, B72.3, BG8, TTF-1, and Napsin A are the best markers of epithelial origin. However, variations in antibody staining are seen between laboratories; therefore, the guidelines do not recommend a specific group of antibodies[9].

In contrast, the inconsistency in the response of the mesothelial spectrum markers calretinin and WT-1 on exfoliated cell blocks selected by our laboratory does not categorize the mesothelial origin, although the sensitivity of WT-1 for mesothelioma ranges from 70% to 100%. An analysis of a single-center study found that among 218 cases of peritoneal mesothelioma, all patients were immunoreactive positive for calretinin, 94% of whom exhibited WT1 expression. In the remaining 13 WT-1-negative cases, the laboratory used four negative malignant epithelial tumor markers, including B72.3 (n = 13), CEA (n = 11), Ber-EP4 (n = 12), and CD15 (n = 12), to support the diagnosis of mesothelioma[10]. Establishing mesothelial lineage is the first step in diagnosing malignant mesothelioma (MM), and it is particularly important to select markers with high sensitivity and specificity. Recent studies have shown that HEG1 shows higher sensitivity and specificity than calmodulin, D2-40, and WT-1, which may serve as an effective diagnostic tool for MM[11].

PAX-8 is a transcription factor involved in the development of the thyroid, kidney, and Müllerian duct systems and is also expressed in the thyroid, renal cell, ovarian, cervical, endometrial, thymic epithelial, and ocular epithelial cancers. Although its immunoreactivity in peritoneal mesothelioma ranges from 0% to 9%, PAX-8 remains a key IHC marker to discriminate between carcinoma and mesothelioma, especially in a group of negative antibodies[10,12]. CK20 is an important component of the intestinal epithelium and is expressed exclusively on the gastrointestinal epithelium, urinary epithelium, Merkel cells of the epidermis, and malignant tumors originating from these sites. Studies have shown a lack of CK20 reactivity in MM; only one case report of diffuse and strongly positive mesothelioma for CK20 is available[13]. Therefore, the IHC results in this case showing cancer markers of CK20 (-), Pax-8 (-), CEA (-), and TTF-1 (-) largely support the diagnosis of mesothelioma.

In some cases, morphologically distinguishing benign from malignant mesothelial hyperplasia is difficult, especially when evaluating effusion cell specimens. The five mesothelioma markers desmin, GLUT-1, EMA, p53, and IMP-3 are no longer recommended for the routine differentiation of benign from malignant mesothelial lesions[14]. p16 pure hapten deletion was found to be 100% specific for MM by FISH. However, it has never been reported in benign mesothelial hyperplasia. Therefore, the detection of p16 (CDKN2A) deletion by FISH, in this case, supported the diagnosis of MM. Similarly, BaP1, MTAP, 5-hmC, and EZH2 have high specificity for MM. A new routine diagnostic marker will be developed in the future after combining these markers or changing their detection methods to improve sensitivity[15]. Some studies have also confirmed the value of circulating and tissue microRNAs in the early diagnosis of MM. However, large-scale and standardized studies are needed to verify and evaluate the clinical relevance of circulating and tissue microRNAs[16].

In terms of differential diagnosis, peritoneal carcinoma can have an ovarian, fallopian tube, gastric, pancreatic, colonic, renal, pulmonary, and, more rarely, breast origin. In this case report, the negative CK20, CDX2, TTF1, CEA, PAX8, and Des are important to exclude gastrointestinal, pulmonary, ovarian, and renal tumor metastases.

MPM is considered to be a chemotherapy-resistant malignant tumor. CRS combined with HIPEC is a commonly used treatment regimen for MPM. Some studies have found that this regimen can improve the survival rate of patients with MPM. However, the CT results of the patient revealed no signs of tumor in the peritoneum, which might be due to the small tumor size. Therefore, bidirectional chemotherapy was used instead.

Bidirectional chemotherapy is a promising, well-tolerated treatment that can simultaneously kill cancer cells from both sides (peritoneal cavity and peripheral blood vessels) via simultaneous intraperitoneal perfusion and intravenous administration. It can also improve resection rates in patients with diffuse MPM, which was initially considered unresectable or borderline resectable[17]. The best treatment is cisplatin in combination with pemetrexed, while the combination of cisplatin and gemcitabine is the second choice[18]. HIPEC is a potential therapeutic strategy for patients with refractory malignant ascites who cannot undergo curative CRS. Randle et al[19] found complete resolution of malignant ascites in 93% of patients after HIPEC. In the present case, the patient also had a significant resolution of ascites after receiving a course of HIPEC.

At present, immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy is the focus of anti-tumor therapy. The future challenge will be to assess a four-drug combination with bevacizumab, anti-PD-1/PDL1 antibody, pemetrexed, and platinum, which has recently been proven efficient in patients with non-small cell lung cancer, given that a biological rationale supports the synergy between anti-VEGF therapy and immuno-therapeutics. Local regional adjuvant therapy (early postoperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy and/or normothermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy) associated with systemic chemotherapy may also be beneficial in adequate clinical conditions[20]. A multi-center, double-blind, randomized phase 3 trial of nivolumab (an antibody against PD-1) was conducted in patients with MM who had previously relapsed after first-line platinum chemotherapy. The results showed that the median progression-free survival and median overall survival was 3.0 and 10.2 mo, respectively, in the nivolumab group and 1.8 and 6.9 mo, respectively, in the placebo group[21]. In a double-blind, phase 3 randomized study of nivolumab vs. placebo in patients with unresectable MM, the survival (median, 9.2 vs 6.6 mo) and PFS (time to event) were longer (median, 3.0 vs 1.8 mo) after nivolumab treatment[22]. In the two open-label, single-arm, phase 2 studies, among patients with measurable and unresectable MM and/or disease progression after the first-line platinum regimen, 3%-7% of patients achieved partial remission, and 31%-38% of patients were under control after receiving trametamab[23]. However, in the subsequent double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2B trials, the median overall survival of the intention-to-treat population did not differ between the treatment and comfort groups[24]. Although some data suggested that immunotherapy had a certain effect on MPM, this case report did not support the aforementioned treatment strategy, and hence more clinical studies are needed for confirmation in the future.

Patients with MPM have a poor prognosis with a median survival of 3-6 mo if not treated, 11-17 mo with chemotherapy alone, and 55-61 mo with CRS combined with HIPEC, with a 5-year survival rate of 52%[25,26]. Our patient did not undergo surgery and died after two courses of bidirectional chemotherapy (with the addition of intraperitoneal thermoperfusion chemotherapy and immunotherapy in the second course), just 2 mo after the first visit[27]. The patient's sudden disease progression after receiving chemotherapy might be related to insensitivity to chemotherapy or the high disease progression after treatment with immune checkpoint inhibitors[28], in addition to the p16/CDKN2A deletion and negative WT-1 expression that was related to a poorer prognosis[29].

In this study, we reported the case of a female patient with peritoneal mesothelioma, which is a rare and difficult-to-diagnose malignancy. The patient presented with massive ascites, no history of asbestos exposure, and no obvious signs of tumor on CT, and was finally diagnosed based on the histology and immunohistochemistry of cells shed from the ascites. Unfortunately, the patient died due to disease progression after two courses of anti-neoplastic therapy. Clinicians should consider the possibility of MPM in case of massive unexplained ascites. In addition, patients with MPM have a poor prognosis, and CRS combined with HIPEC for patients who can tolerate surgery or have resectable lesions may improve the prognosis.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Oncology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Mahfuz AMUB, Bangladesh; Munasinghe B, Sri Lanka S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: A P-Editor: Yan JP

| 1. | Broeckx G, Pauwels P. Malignant peritoneal mesothelioma: a review. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2018;7:537-542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Llanos MD, Sugarbaker PH. Symptoms, signs and radiologic findings in patients having reoperative surgery for malignant peritoneal mesothelioma. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2017;43:138-143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Uhlenhopp DJ, Saliares A, Gaduputi V, Sunkara T. An Unpleasant Surprise: Abdominal Presentation of Malignant Mesothelioma. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep. 2020;8:2324709620950121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kalaycı O, Cansu GB, Taşkıran B, Eren Ö. A Rare Complication of Diffuse Malignant Peritoneal Mesothelioma: Spontaneous Ileal Perforation. Indian J Surg Oncol. 2019;10:465-469. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Greenbaum A, Alexander HR. Peritoneal mesothelioma. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2020;9:S120-S132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hong S, Bi MM, Zhao PW, Wang XU, Kong QY, Wang YT, Wang L. Malignant peritoneal mesothelioma in a patient with intestinal fistula, incisional hernia and abdominal infection: A case report. Oncol Lett. 2016;11:2047-2050. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Pickhardt PJ, Perez AA, Elmohr MM, Elsayes KM. CT imaging review of uncommon peritoneal-based neoplasms: beyond carcinomatosis. Br J Radiol. 2021;94:20201288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Yan TD, Haveric N, Carmignani CP, Bromley CM, Sugarbaker PH. Computed tomographic characterization of malignant peritoneal mesothelioma. Tumori. 2005;91:394-400. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Husain AN, Colby TV, Ordóñez NG, Allen TC, Attanoos RL, Beasley MB, Butnor KJ, Chirieac LR, Churg AM, Dacic S, Galateau-Sallé F, Gibbs A, Gown AM, Krausz T, Litzky LA, Marchevsky A, Nicholson AG, Roggli VL, Sharma AK, Travis WD, Walts AE, Wick MR. Guidelines for Pathologic Diagnosis of Malignant Mesothelioma 2017 Update of the Consensus Statement From the International Mesothelioma Interest Group. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2018;142:89-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 328] [Cited by in RCA: 401] [Article Influence: 50.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Tandon RT, Jimenez-Cortez Y, Taub R, Borczuk AC. Immunohistochemistry in Peritoneal Mesothelioma: A Single-Center Experience of 244 Cases. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2018;142:236-242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Naso JR, Tsuji S, Churg A. HEG1 Is a Highly Specific and Sensitive Marker of Epithelioid Malignant Mesothelioma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2020;44:1143-1148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Khizer K, Padda J, Khedr A, Tasnim F, Al-Ewaidat OA, Patel V, Ismail D, Campos VYM, Jean-Charles G. Paired-Box Gene 8 (PAX8) and Its Association With Epithelial Carcinomas. Cureus. 2021;13:e17208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Manur R, Lamzabi I. Aberrant Cytokeratin 20 Reactivity in Epithelioid Malignant Mesothelioma: A Case Report. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2019;27:e93-e96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Churg A, Sheffield BS, Galateau-Salle F. New Markers for Separating Benign From Malignant Mesothelial Proliferations: Are We There Yet? Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2016;140:318-321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Chapel DB, Schulte JJ, Husain AN, Krausz T. Application of immunohistochemistry in diagnosis and management of malignant mesothelioma. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2020;9:S3-S27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 19.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 16. | Martinez VD, Marshall EA, Anderson C, Ng KW, Minatel BC, Sage AP, Enfield KSS, Xu Z, Lam WL. Discovery of Previously Undetected MicroRNAs in Mesothelioma and Their Use as Tissue-of-Origin Markers. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2019;61:266-268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Le Roy F, Gelli M, Hollebecque A, Honoré C, Boige V, Dartigues P, Benhaim L, Malka D, Ducreux M, Elias D, Goéré D. Conversion to Complete Cytoreductive Surgery and Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy for Malignant Peritoneal Mesothelioma After Bidirectional Chemotherapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24:3640-3646. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kusamura S, Kepenekian V, Villeneuve L, Lurvink RJ, Govaerts K, De Hingh IHJT, Moran BJ, Van der Speeten K, Deraco M, Glehen O; PSOGI. Peritoneal mesothelioma: PSOGI/EURACAN clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2021;47:36-59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Randle RW, Swett KR, Swords DS, Shen P, Stewart JH, Levine EA, Votanopoulos KI. Efficacy of cytoreductive surgery with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy in the management of malignant ascites. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21:1474-1479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Sugarbaker PH. Update on the management of malignant peritoneal mesothelioma. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2018;7:599-608. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Lapidot M, Saladi SV, Salgia R, Sattler M. Novel Therapeutic Targets and Immune Dysfunction in Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:806570. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Fennell DA, Ewings S, Ottensmeier C, Califano R, Hanna GG, Hill K, Danson S, Steele N, Nye M, Johnson L, Lord J, Middleton C, Szlosarek P, Chan S, Gaba A, Darlison L, Wells-Jordan P, Richards C, Poile C, Lester JF, Griffiths G; CONFIRM trial investigators. Nivolumab versus placebo in patients with relapsed malignant mesothelioma (CONFIRM): a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22:1530-1540. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 172] [Cited by in RCA: 166] [Article Influence: 41.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Calabrò L, Morra A, Fonsatti E, Cutaia O, Fazio C, Annesi D, Lenoci M, Amato G, Danielli R, Altomonte M, Giannarelli D, Di Giacomo AM, Maio M. Efficacy and safety of an intensified schedule of tremelimumab for chemotherapy-resistant malignant mesothelioma: an open-label, single-arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Respir Med. 2015;3:301-309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 150] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 24. | Maio M, Scherpereel A, Calabrò L, Aerts J, Perez SC, Bearz A, Nackaerts K, Fennell DA, Kowalski D, Tsao AS, Taylor P, Grosso F, Antonia SJ, Nowak AK, Taboada M, Puglisi M, Stockman PK, Kindler HL. Tremelimumab as second-line or third-line treatment in relapsed malignant mesothelioma (DETERMINE): a multicentre, international, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2b trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:1261-1273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 281] [Cited by in RCA: 324] [Article Influence: 40.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 25. | Verma V, Sleightholm RL, Rusthoven CG, Koshy M, Sher DJ, Grover S, Simone CB 2nd. Malignant Peritoneal Mesothelioma: National Practice Patterns, Outcomes, and Predictors of Survival. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;25:2018-2026. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Naffouje SA, Tulla KA, Salti GI. The impact of chemotherapy and its timing on survival in malignant peritoneal mesothelioma treated with complete debulking. Med Oncol. 2018;35:69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Jänne PA, Wozniak AJ, Belani CP, Keohan ML, Ross HJ, Polikoff JA, Mintzer DM, Taylor L, Ashland J, Ye Z, Monberg MJ, Obasaju CK. Open-label study of pemetrexed alone or in combination with cisplatin for the treatment of patients with peritoneal mesothelioma: outcomes of an expanded access program. Clin Lung Cancer. 2005;7:40-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Ikushima H, Sakatani T, Ohara S, Takeshima H, Horiuchi H, Morikawa T, Usui K. Cisplatin plus pemetrexed therapy and subsequent immune checkpoint inhibitor administration for malignant peritoneal mesothelioma without pleural lesions: Case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99:e19956. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Pezzuto F, Vimercati L, Fortarezza F, Marzullo A, Pennella A, Cavone D, Punzi A, Caporusso C, d'Amati A, Lettini T, Serio G. Evaluation of prognostic histological parameters proposed for pleural mesothelioma in diffuse malignant peritoneal mesothelioma. A short report. Diagn Pathol. 2021;16:64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |