Published online Oct 6, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i28.10293

Peer-review started: May 19, 2022

First decision: July 12, 2022

Revised: July 27, 2022

Accepted: August 25, 2022

Article in press: August 25, 2022

Published online: October 6, 2022

Processing time: 130 Days and 18.9 Hours

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)-related cirrhosis is mainly caused by NAFLD by causing inflammation which leads to fibrosis. The role of leptin in NAFLD-related cirrhosis has been rarely reported.

This study presents the case of a 65-year-old male patient who was referred to The First Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi University of Chinese Medicine, Guangxi, Chi

Although the occurrence of marasmus NAFLD-related cirrhosis is rare, it needs to be distinguished from other liver diseases, including viral hepatitis, drug-induced liver disease, Wilson's disease and autoimmune liver disease. Aggressive treatment is needed to prevent the progression of NAFLD-related cirrhosis.

Core Tip: The patients with marasmus might also develop non-alcoholic fatty liver disease cirrhosis and it needs to be distinguished from other liver diseases, including viral hepatitis and drug-induced liver disease. Early liver biopsy histopathology and the liver fibrosis scoring system are important methods for the diagnosis of liver cirrhosis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) patients. Aggressive treatment is needed to prevent the progression of NAFLD-related cirrhosis, thereby requiring immediate clinical attention.

- Citation: Nong YB, Huang HN, Huang JJ, Du YQ, Song WX, Mao DW, Zhong YX, Zhu RH, Xiao XY, Zhong RX. Rare leptin in non-alcoholic fatty liver cirrhosis: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(28): 10293-10300

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i28/10293.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i28.10293

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) refers to intracellular fat deposition in the liver tissues caused by liver-damaging factors other than excessive alcohol consumption, intracellular fat accumulation without inflammation or fibrosis (simple hepatic steatosis), hepatic steatosis with necrotizing inflammation and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH)[1]. The occurrence of NAFLD is related to multiple factors such as insulin resistance, imbalance of intestinal flora, oxidative stress, inflammation and mitochondrial damage[2-4]. Around 20% of NASH patients might progress to cirrhosis[5]. The pre

A 65-year-old male was presented to Yongning Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Nanning, Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, China, with liver cirrhosis for more than 1 mo.

The patient had diffuse liver disease for more than 1 mo which was identified by physical examination. He was treated in the Traditional Chinese Medicine Hospital of Yongning District, Nanning, Guangxi, China, in June 2020 and was diagnosed with liver cirrhosis. He was discharged after treatments for protecting the liver and lowering the related enzyme levels. Then, the patient was admitted to the First Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi University of Chinese Medicine, Guangxi, China, for further diagnosis and treatment. The patient’s symptoms at the time of admission to the hospital included mild fatigue, a good diet, poor sleep and two kilograms of weight loss in the past half a year.

The patient’s history showed that he used to eat a lot and had lost weight since childhood. He had a history of chronic gastritis for 8 years as well as pulmonary tuberculosis and was a hepatitis B virus carrier. The recent out-of-hospital tests were negative for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and hepatitis B viral DNA. Moreover, he had no history of hepatitis, alcohol or drug abuse.

The patient's medical history shows that he ate a lot from an early age and had lost weight.

The examination at the time of admission showed the following results: blood pressure 110/62 mmHg; height 165 cm; and weight 51.5 kg. The patient showed emaciation (Figure 1). The patient had a body mass index (BMI) of 18.92 kg/m2 and had no apparent heart and lung abnormalities. His abdomen was flat and no liver palm or spider nevus were seen. The liver and spleen were not palpated showing negative mobility. There was no edema in both the lower limbs.

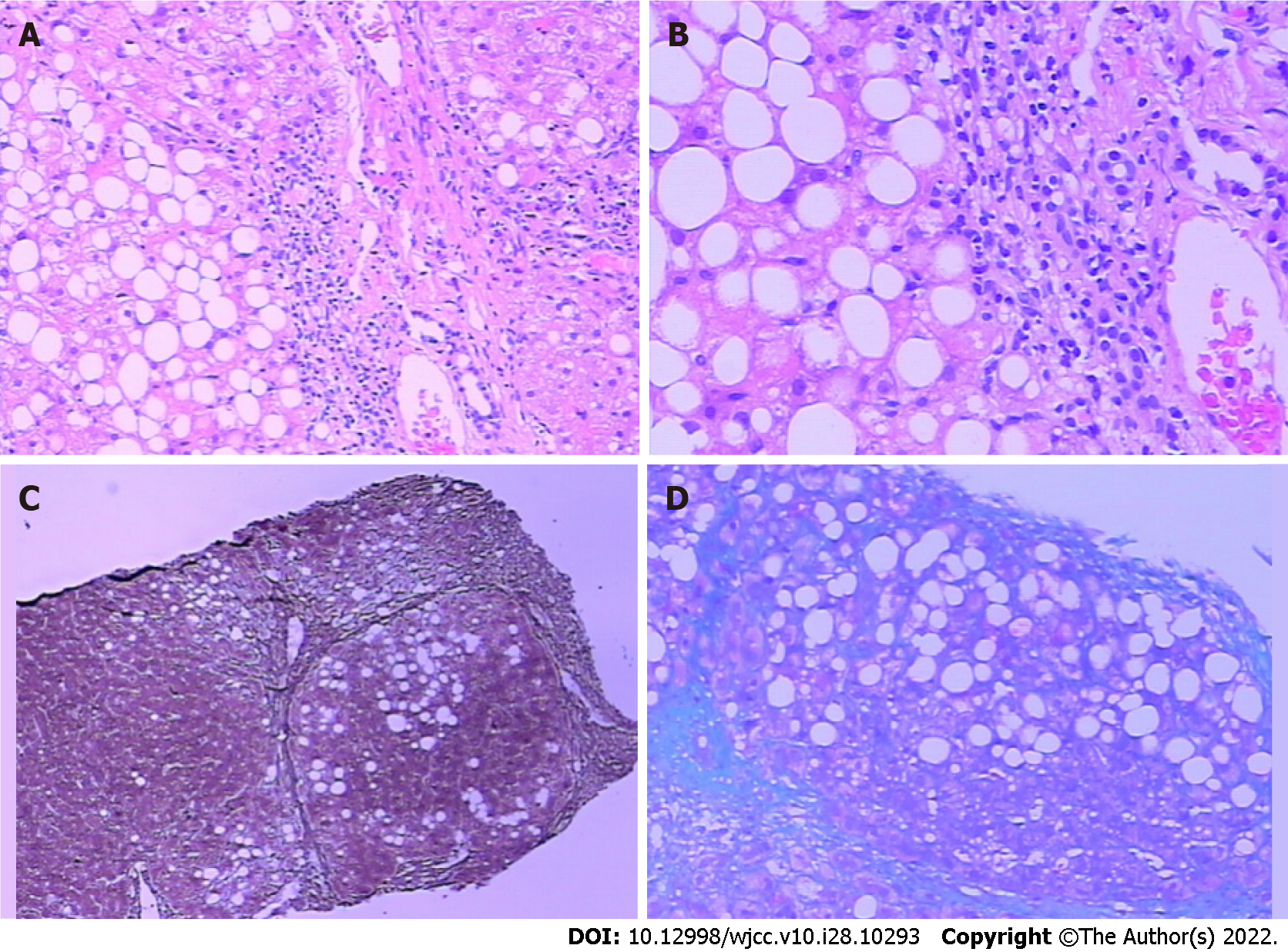

Auxiliary examination showed the following results. Antinuclear antibody was positive. The indicator of liver fibrosis included hyaluronic acid 472.744 ng/mL; type IV collagen 144.548 ng; anti-hepatitis C virus antibody 0.1S; and hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) 19.36 g; anti-hepatitis C virus 0.15 g; white blood cell count 4.3 × 109; liver function: hepatitis B virus 5: HBsAg negative; anti-HBs negative; HBeAg negative; anti-HBe positive; and anti-HBc positive. There were no abnormalities in the renal function, electrolytes, blood lipids, blood coagulation, tumor, and human immunodeficiency virus antigen and antibody. Based on these symptoms and examination results, the patient was diagnosed with liver cirrhosis. Due to the normal results of the five items of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus, liver cirrhosis caused by viral hepatitis was excluded. The transaminase level slightly increased with positive results for antinuclear antibodies. The possibility of autoimmune hepatitis was not ruled out and the diagnosis was further confirmed using liver biopsy. Pathological analysis (Figure 2) showed the hepatic lobules were damaged and had moderate bullous steatosis of hepatocytes with several punctate and focal necrotic foci. Five portal areas showed the infiltration of lymphocytes and individual neutrophils, no facial inflammation and high plasma cell infiltration, fibrous tissue hyperplasia with false lobule formation, cell tube hyperplasia, liver inflammation and no autoimmune hepatitis. Immunohistochemical analysis showed cytokeratin (CK) 8/18-positive epithelial cells, Hepat-positive hepatocytes, CK7-, CK19-, and cluster of differentiation (CD) 10-positive bile duct epithelial cells, CD34-positive endothelial cells, 1% Ki67-positive cells, while the immunostaining for HBsAg and HBcAg showed negative results. During hospitalization, the patient was treated with diammonium glycyrrhizinate enteric-coated capsules for liver protection and lowering the levels of related enzymes. The patient was discharged after showing improvement. After discharge, the patient was prescribed methylprednisolone tablets and examined regularly at the outpatient clinic. The transaminase index did not decrease significantly after immunosuppression, liver protection and enzyme lowering treatments; however, the transaminase level increased significantly (Table 1).

| Liver function | TBIL in µmol/L | IBIL in µmol/L | DBIL in µmol/L | ALT in U/L | AST in U/L | ALP in U/L | GGT in U/L | TBA in µmol/L |

| 2020.07.08 | 10.9 | 5.8 | 5.1 | 72 | 86 | 153 | 373 | 5.3 |

| 2020.07.16 | 10.2 | 5.3 | 4.9 | 136 | 116 | 141 | 339 | 3.9 |

| 2020.07.25 | 13.6 | 5.9 | 7.7 | 129 | 78 | 144 | 433 | 6.9 |

| 2020.08.04 | 12.7 | 5.0 | 7.7 | 238 | 115 | 148 | 737 | 10.9 |

| 2020.09.11 | 8.2 | 3.6 | 4.6 | 120 | 58 | 128 | 383 | 26.9 |

| 2020.09.16 | 6.8 | 3.0 | 3.8 | 76 | 32 | 95 | 216 | 12.6 |

| 2020.09.25 | 7.1 | 3.1 | 4.0 | 29 | 30 | 111 | 176 | 22.4 |

| 2020.12.12 | 14.9 | 6.8 | 8.1 | 58 | 75 | 109 | 140 | 8.8 |

| 2021.05.05 | 6.0 | 2.8 | 3.2 | 40 | 59 | 193 | 276 | 10.9 |

In order to further explore the underlying mechanism of high transaminase levels caused by liver cirrhosis, the patient was hospitalized again on September 10, 2020. The patient’s blood tests were performed, which showed IgA 2.81 g/L, IgG 12.89 g/L, IgM 0.18 g/L, and low-density lipoprotein 1.38 mmol/L. For the liver function, the alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, and total bile acid levels were 120 µmol/L, 58 µmol/L, and 26.9 µmol/L, respectively. The patient was negative for hepatitis A, C, and E viral antibodies. However, the patient was negative for HBsAg, HBs, and HBeAg and positive for HBe and HBc with positive antinuclear antibodies. Hepatitis B viral DNA was lower than the detectable value. The tests for 12 anti-ENA antibodies showed the following results: anti-SS-An antibody (+ +); anti-SS-B antibody (+ +); anti-histone antibody (+ +); and carcinoembryonic antigen 5.3 ng/mL. The glucose level was 5.01 mmol/L. The determination of glycosylated hemoglobin showed the following results: Average blood glucose 7.19 mmol/L; total glycosylated hemoglobin 6.96%; non-glycosylated hemoglobin pyridoxylated normal adult human hemoglobin 93.04%; glycosylated hemoglobin 1.16%; and glycosylated hemoglobin 5.80%. The blood routine tests, coagulation four items, plasma D-dimer determination, human immunodeficiency virus antigen-antibody mixture test, tumor 5 items, electrolyte, and renal function showed normal results.

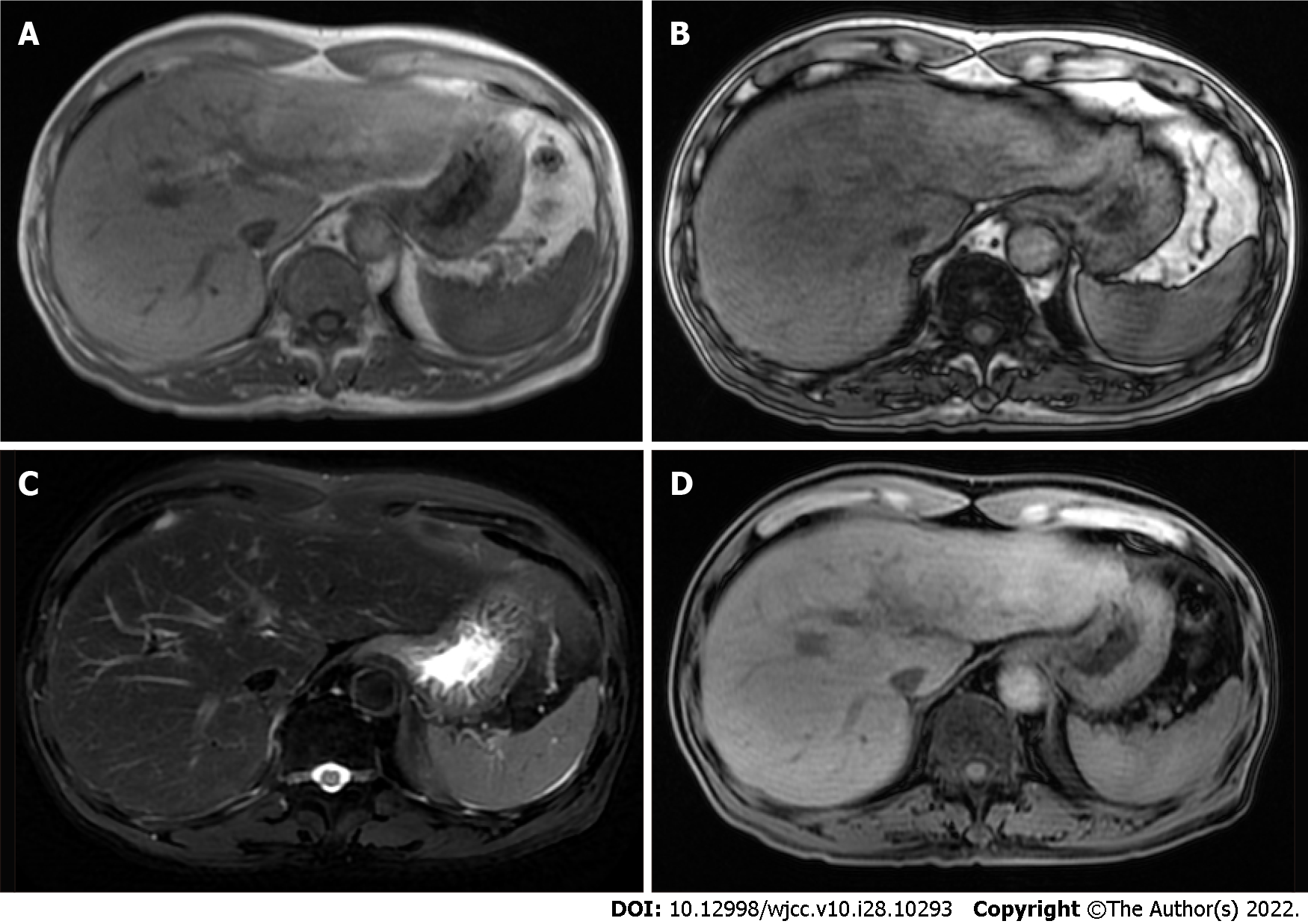

The salivary gland imaging showed that the secretion and excretion functions of the right parotid gland and bilateral submandibular gland were normal. The secretion function of the left parotid gland decreased slightly, although the excretion function was normal. Thyroid size and technetium uptake function were normal. Plain and enhanced nuclear magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the upper abdomen (Figure 3) showed an enlarged left lobe of the liver. The proportion of the liver lobes was asymmetrical. The T1 weighted imaging (T1WI) revealed diffuse nodules in the hepatic parenchyma, whereas patchy enhancement was observed in the liver. The portal vein phase and delayed phase showed similar results. The portal vein trunk and its branches displayed normal development.

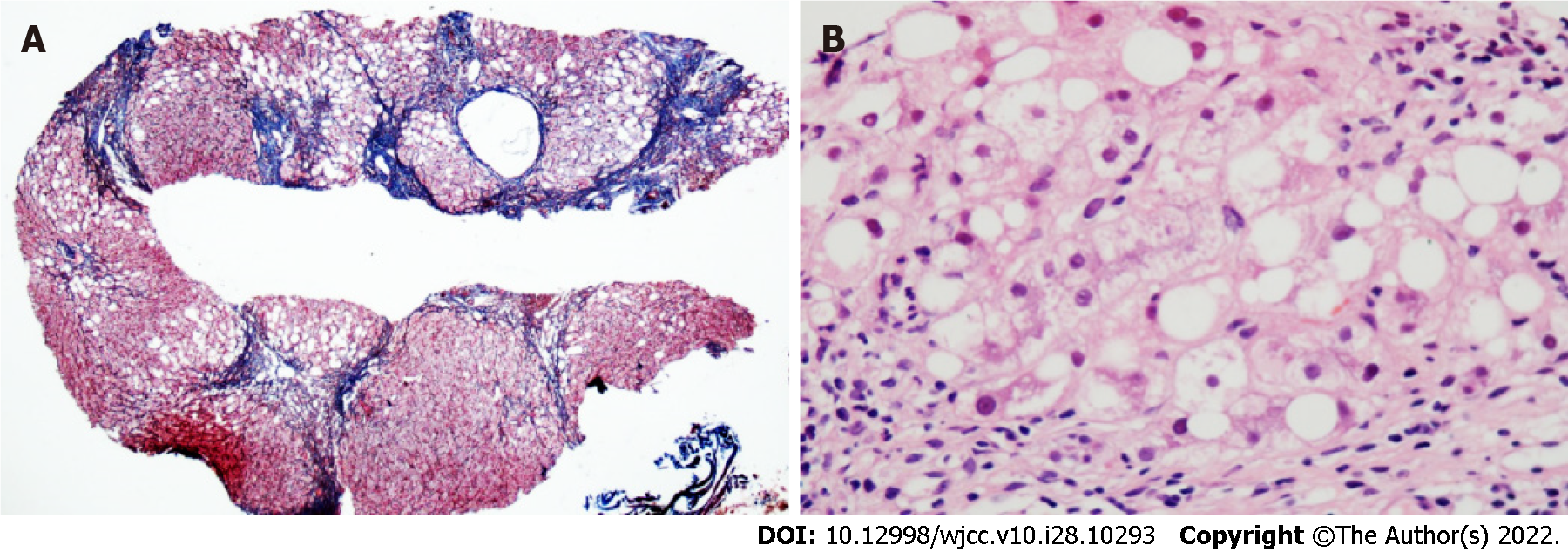

Hepatitis A, B, C and E viral infections were not detected during the two hospitalization periods. Accordingly, liver cirrhosis caused by viral hepatitis was ruled out. The patient showed repeatedly increased levels of transaminase for unknown reasons and the hormone treatment did not show good effects. Autoimmune liver disease was excluded from endocrinology consultation based on the anti-SS-An antibody (+ +), anti-SS-B antibody (+ +), and anti-histone antibody (+ +) results. The complement C3 and C4 Levels were 1.08 g/L and 0.31 g/L, respectively. The clonorchiasis antibody test was negative. The anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody vasculitis test was negative. The ophthalmology examination ruled out hepatolenticular degeneration. Glucose and glycosylated hemoglobin indices were normal; therefore, the fats-accumulated hepatopathy caused by diabetes was excluded. For thyroid function, the T3 Level was 1.12 nmol, the LMagre T4 Level was 74.5 nmol, the pound LMag FT3 Level was 4.8 pmol, the pound LMag FT4 Level was 11.81 pmol, and the TSH level was 0.60 mIU shock L. The levels of five sex hormones (male) were as follows: LH 4.47 mIU/mL; FSH level 13.9 mIU/mL; testosterone level 6.6 ng/mL; prolactin level 184 mIU/mL; and E2 Level 36.1 pg/mL; therefore, metabolic lesions were excluded and hormone treatment was stopped. After discharging the patient from the hospital to the outpatient clinic, the repeated elevation of transaminase was performed (Table 1). Liver biopsy specimens were sent to Beijing China-Japan Friendship Hospital, Beijing, China, for testing. The pathological analysis showed that there were 19 small and medium-sized portal areas with enlarged inflammation in the section (Figure 4). The neighboring portal areas were often close to and connected with most of the fibrous septum of different widths, separating most of the liver parenchyma, while some of them showed nodules (Figure 4, reticulation + Masson). The mild to moderate infiltration of mixed inflammatory cells, dominated by mononuclear cells in the interstitium of the portal area and necrotic zone (in which plasma cells were rare) and small bile ducts, were also observed. Most of the hepatocytes in the separated liver parenchyma showed vesicular steatosis, mainly distributed in about 60% of the portal area and around the necrotic zone. During this period, most of the hepatocytes swelled like balloons, while a few contained Mallory bodies (Figure 4, hematoxylin and eosin staining), which were accompanied by extensive peri-sinus fibrosis. In addition, a small number of small necrotic foci were scattered [NAFLD-activity score (NAS) = 2 + 1 + 2 = 5]. Based on the pathological analysis of liver functions, the patient was diagnosed with NASH fibrosis stage 4. The clinical diagnosis was NAFLD-related early liver cirrhosis.

Due to the patient’s weight loss combined with the signs and symptoms as well as auxiliary examination, the patient was finally diagnosed with NAFLD-related cirrhosis (leptin type).

The patient was hospitalized again after confirming the diagnosis and discharged after treatment. The patient was prescribed to avoid a high-fat diet and overeating and increase outdoor exercise. The patient was treated with an oral compound Yiganling capsule, diammonium glycyrrhizinate enteric capsule for liver protection and lowering the levels of related enzymes, self-made Zhuanggan Zhuyu pill and Yuzhuozhixiao pills.

The patient was treated with diammonium glycyrrhizinate intestinal capsule, self-made Zhuanggan Zhuyu pills and Yuzhuo Zhixiao pills. The patient was regularly followed-up in the outpatient clinic and showed no discomfort at the time of this study.

NAFLD is the main cause of liver cirrhosis. The risk factors for developing liver cirrhosis in NAFLD patients included metabolic factors (diabetes, hyperlipidemia, obesity and hypertension), NASH, gene polymorphisms, and older age[8-10]. The clinical manifestations of cirrhosis caused by NAFLD were similar to those found in cirrhosis caused by other factors. Hence, NAFLD-related cirrhosis was hard to diagnose. The increase in NAFLD and emaciated NAFLD in developing countries has increased with stressful lifestyles. Studies reported that the pathogenesis of emaciated NAFLD patients was closely related to the levels of hormones related to fat mobilization, such as insulin or TSH, and visceral fat deposition was more common in obese patients[11]. Therefore, the presence and severity of fatty liver could be assessed by measuring the abdominal circumference and BMI. The patient in the current case study was emaciated (Figure 1). His BMI was 18.92 kg/m2, and diffuse liver lesions were observed in the physical examination in 2020. There was a continuous increase in the levels of transaminase; therefore, a liver biopsy was performed to rule out the possibility of autoimmune hepatitis. Hormone therapy could not alleviate the condition and the transaminase levels continuously increased. Following repeated examinations, Wilson's disease, immune liver disease, fatty liver disease caused by diabetes and metabolic lesions were excluded. The liver biopsy was finally conducted for further pathological examination which showed the characteristics of NASH. The sign and symptoms combined with the exclusion of multiple possibilities and two pathological examination features, the patient was finally diagnosed with leptin type NAFLD-related cirrhosis. Based on the patient's diagnosis and treatment, this study suggested that NAFLD might not increase the risk of obesity. The clinical manifestations were not obvious and there might be a single abnormal index, such as transaminase, which could be ignored.

Early liver biopsy histopathology and the liver fibrosis scoring system are important methods for the diagnosis of liver cirrhosis in NAFLD patients. Its treatment involves a low-sugar and low-fat diet, weight loss, abstaining from alcohol consumption, controlling other cirrhosis-related factors, proper exercise and controlling liver fibrosis (drugs). The prognosis of NAFLD-related liver cirrhosis is poor. Marasmus NAFLD cirrhosis has gradually been focused on. In future studies, the application of artificial intelligence might speed up the studies to identify the risk factors of emaciated NAFLD, and provide further specific treatment to patients with early intervention to hinder the progress of emaciated NAFLD.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Dentistry, oral surgery and medicine

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Fazilat-Panah D, Iran; Sharaf MM, Syria; Sharaf MM, Syria S-Editor: Wang DM L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Wang DM

| 1. | Li B, Zhang C, Zhan YT. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Cirrhosis: A Review of Its Epidemiology, Risk Factors, Clinical Presentation, Diagnosis, Management, and Prognosis. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;2018:2784537. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Yilmaz Y. Is nonalcoholic fatty liver disease the hepatic expression of the metabolic syndrome? World J Hepatol. 2012;4:332-334. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Musso G, Gambino R, Biroli G, Carello M, Fagà E, Pacini G, De Michieli F, Cassader M, Durazzo M, Rizzetto M, Pagano G. Hypoadiponectinemia predicts the severity of hepatic fibrosis and pancreatic Beta-cell dysfunction in nondiabetic nonobese patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2438-2446. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Tokushige K, Ikejima K, Ono M, Eguchi Y, Kamada Y, Itoh Y, Akuta N, Yoneda M, Iwasa M, Otsuka M, Tamaki N, Kogiso T, Miwa H, Chayama K, Enomoto N, Shimosegawa T, Takehara T, Koike K. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease/nonalcoholic steatohepatitis 2020. J Gastroenterol. 2021;56:951-963. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 183] [Cited by in RCA: 178] [Article Influence: 44.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Matteoni CA, Younossi ZM, Gramlich T, Boparai N, Liu YC, McCullough AJ. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a spectrum of clinical and pathological severity. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:1413-1419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2357] [Cited by in RCA: 2344] [Article Influence: 90.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Wu Y, Zheng Q, Zou B, Yeo YH, Li X, Li J, Xie X, Feng Y, Stave CD, Zhu Q, Cheung R, Nguyen MH. The epidemiology of NAFLD in Mainland China with analysis by adjusted gross regional domestic product: a meta-analysis. Hepatol Int. 2020;14:259-269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Maheshwari A, Thuluvath PJ. Cryptogenic cirrhosis and NAFLD: are they related? Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:664-668. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Bhadoria AS, Kedarisetty CK, Bihari C, Kumar G, Jindal A, Bhardwaj A, Shasthry V, Vyas T, Benjamin J, Sharma S, Sharma MK, Sarin SK. Impact of family history of metabolic traits on severity of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis related cirrhosis: A cross-sectional study. Liver Int. 2017;37:1397-1404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Huang TD, Behary J, Zekry A. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a review of epidemiology, risk factors, diagnosis and management. Intern Med J. 2020;50:1038-1047. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 35.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Frith J, Day CP, Henderson E, Burt AD, Newton JL. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in older people. Gerontology. 2009;55:607-613. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in RCA: 183] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Pallayova M, Taheri S. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in obese adults: clinical aspects and current management strategies. Clin Obes 2014; 4: 243-253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |