Published online Oct 6, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i28.10097

Peer-review started: June 3, 2022

First decision: June 16, 2022

Revised: June 27, 2022

Accepted: August 21, 2022

Article in press: August 21, 2022

Published online: October 6, 2022

Processing time: 115 Days and 23.5 Hours

Dementia is a severe neurological and psychological disease that occurs in older adults worldwide. The knowledge and attitude of medical-vocational college students play an important role in supporting primary healthcare systems.

To investigate the level of knowledge, contact experience, and attitudes toward dementia among medical-vocational college students in China.

A cross-sectional survey was conducted, and 3-year medical and medical-related students from eight vocational colleges in Anhui province were recruited. The contact experience, attitudes, and knowledge level of students toward dementia were assessed using a questionnaire designed according to the Chinese version of the Alzheimer’s Disease Knowledge Scale (ADKS).

A total of 2444 medical and medical-related students completed the survey, of whom 86.7% of respondents had interests and concerns regarding Alzheimer’s disease (AD), and 29.2% of respondents had experiences of contact with dementia patients. Overall attitudes toward dementia were negative. Only 35.4% of stu

Dementia-related knowledge of medical-vocational college students was at a medium level, and their overall attitudes toward dementia were negative.

Core Tip: Chinese medical-vocational college students mainly work in primary healthcare systems following graduation and have significant opportunities to have contact with dementia patients and their family members. The present study aimed to examine the contact experience, attitudes, and knowledge level of medical-vocational college students toward dementia. Results showed that dementia-related knowledge was at a medium level among medical-vocational college students, and their willingness to provide care for Alzheimer’s disease was low. Moreover, students held negative attitudes toward dementia patients.

- Citation: Liu DM, Yan L, Wang L, Lin HH, Jiang XY. Dementia-related contact experience, attitudes, and the level of knowledge in medical vocational college students. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(28): 10097-10108

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i28/10097.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i28.10097

China is the most populous country in the world. According to data reported by the Seventh National Population Census, the current population of China is over 1.41 billion, and the number of people aged ≥ 60 years old has reached approximately 264 million, which accounts for 18.7% of the total population. Dementia is positively correlated with advanced age. There is a high incidence of dementia among people aged over 65years, and the prevalence is estimated to be as high as 24.5% among people aged ≥ 85 years. In 2019, dementia patients in China accounted for approximately 25% of the total number of dementia patients worldwide[1]. The prevalence of dementia in China for individuals aged ≥ 65 years old was 5.6% (3.5%-7.6%) in a multi-regional study conducted in 2019[2]. As life expectancy continues to rise, the total number of patients with dementia will increase significantly according to the population base of middle-aged and old adults. Dementia is a clinical syndrome of progressive deterioration of cognitive abilities and normal daily functioning. These cognitive and behavioral impairments impose noticeable challenges to individuals with dementia, as well as their family members and caregivers. At present, there is no effective therapeutic option for dementia patients. However, patients who receive an early-stage diagnosis can benefit from high-quality care and specific symptomatic treatment, which enable better living conditions, delayed disease progression, and a higher health-related quality of life. Furthermore, family members of such patients will have their psychological and psychiatric needs satisfied, which, in turn, reduces long-term economic burdens[3,4].

Despite the rapid increase in the number of dementia patients, public knowledge regarding dementia remains limited. This deficiency happens not only in the general public and practitioners[5] but also in healthcare professionals working in hospitals[6-8]. In developed countries, less than 50% of dementia patients have been diagnosed[9], and no study to date has comprehensively reported the diagnostic rate of dementia in China. In 2019, a study on the survival of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) patients showed that the patient visit rate within 1 year was 77.43%. A low level of dementia-related knowledge is the most common reason for the lack of diagnoses and effective therapies for AD[1]. Because dementia care is mainly fragmented, uncoordinated, and difficult to navigate, the navigation of dementia patients is of great significance[10]. Nurses face considerable uncertainty in caring for dementia patients and react in various ways to address this uncertainty. In China, the majority of dementia patients are cared for by their family members, although community older adult care services have provided valuable support[11]. Therefore, it is necessary to explore and disseminate dementia-related information, including the risk factors, early-stage symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment methods, not only among professional medical workers and dementia caregivers but also in the general population.

In 2019, the “Healthy China 2030 Planning Outline” was presented by the National Health Com

There are several tools for measuring dementia-related knowledge. They apply primarily to health professionals and caregivers but can also be used for the general population. Some of these tools have not yet been translated into Chinese. The Alzheimer’s Disease Knowledge Scale (ADKS) was developed by Brian in 2009 and was designed for use in both applied and research contexts. It is capable of assessing knowledge about AD among laypeople, patients, caregivers, and professionals. In 2013, the ADKS was translated into Chinese[16] and has been shown to have promising validity and reliability, with internal consistency ranging from 0.732 to 0.879 and good test-retest reliability (0.756). The ADKS comprises 30 “true or false” questions relating to AD, with scores ranging from 0 (the worst) to 30 (the best), and is divided into seven subscales: life impact (questions 1, 11, and 28), risk factors (questions 2, 13, 18, 25, 26, and 27), disease progression (questions 3, 8, 14, and 17), assessment and diagnosis (questions 4, 10, 20, and 21), caregiving (questions 5, 6, 7, 15, and 16), treatment and management (questions 9, 12, 24, and 29), and symptoms (questions 19, 22, 23, and 30).

In the present study, we performed a questionnaire survey among medical-vocational college students to evaluate the level of knowledge, attitudes, and contact experience of dementia patients and investigate whether there are differences in these items between medical and medical-related students. This study will provide guidance for promoting dementia-related medical-vocational programs.

Between October 2020 and January 2021, a cross-sectional research survey was conducted in medical-vocational college students. A total of 2524 students from eight vocational colleges located in Anhui province participated in the questionnaire survey. These eight vocational colleges incorporate both medical and vocational colleges and include medical and medical-related majors. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Freshmen or sophomore students from vocational-medical colleges in medical (school of clinical medicine or school of nursing) and medical-related major programs (school of pharmacy, school of public health, school of dentistry, school of laboratory medicine, and school of rehabilitation); (2) Participants who were able to complete the questionnaire independently; and (3) Participants who were willing to participate in the survey. The collected data were kept confidential and used for academic purposes only.

In addition to the ADKS scale, we used another scale developed by the School of Nursing, Wakayama Medical University (Wakayama, Japan). The translation and back-translation were conducted by two Chinese-Japanese translators, and minor modifications were made with the author’s permission to make the questions more appropriate for Chinese society. We previously used this scale to evaluate students’ contact experience, attitudes, and knowledge of dementia in a university setting. The overall reliability of the questionnaire was 0.876, and Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of each dimension were between 0.693 and 0.901. The dementia-related questionnaire was self-administered and consisted of four sections. Part I included the demographic data of students, such as sex, age, grade, and specialty. Part II assessed students’ interests and contact experience with dementia patients, which included the first time/place of contact, experience/period of living with dementia patients, willingness to participate in dementia care, who they believe should care for dementia patients, and influencing factors. Part III inquired about students’ attitudes towards dementia and comprised 10 items that were categorized into positive and negative affective groups. Part III was scored on a Likert scale from 1 to 4 (a score of 4 indicated “high consideration,” and a score of 1 indicated “never considered”). Part IVcontained 18 questions relating to knowledge about cognitively impaired older people. Respondents were asked to respond with “yes” or “no” for each question. A higher score indicated better knowledge.

All data collectors received standardized training for the study, which covered the criteria and strategy for recruitment, obtaining informed consent, and the use of uniform explanations for ambiguous cases.

The questionnaires were printed for distribution. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Anhui Medical College (Hefei, Anhui Province, China). Written informed consent was obtained from all eligible students before study enrollment. The questionnaires did not contain any recognizable information on responders and were placed in a ballot box on completion.

A total of 50 students were selected for the pre-survey and were asked to complete the questionnaires independently within 20-25 min.

The EpiData software was used to ensure fail-safe entering and documentation of data. Data entry was performed by two research assistants who cross-checked the data to avoid errors. The SPSS 21.0 software (IBM, Armonk, NY, United States) was used for data analysis. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05 for two-tailed tests. Descriptive statistics were used to analyze participants’ general characteristics. Qualitative data are expressed as numbers and percentages. For quantitative data, normally distributed variables are presented as means ± SD, and non-normally distributed variables are described as medians (quartiles). For quantitative data with a normal distribution and homogeneity of variance, differences between groups were analyzed using independent-samples t-tests. To compare data that were not normally distributed or had inhomogeneity of variance between groups, we used the Mann-Whitney U test.

Of the 2524 questionnaires distributed, 2495 questionnaires were returned. However, 51 questionnaires were incomplete and considered invalid for the survey. Finally, 2444 questionnaires were analyzed, providing an effective recovery rate of 96.83%. The effective responders comprised 1251 (51.2%) medical students and 1193 (48.8%) medical-related students, and 62.4% of responders were female. Regarding grade distribution, the proportions of freshmen and sophomores were 54.5%, and 45.5%, respectively. The demographic data of responders are summarized in Table 1.

| Variables | Total | Medical major students | Medical-related major students |

| Specialty | 1251 (51.2) | 1193 (48.8) | |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 1525 (62.4) | 800 (64) | 725 (60.8) |

| Male | 919 (37.6) | 451 (36) | 468 (39.2) |

| Grade | |||

| Freshman | 1332 (54.5) | 729 (58.3) | 603 (50.5) |

| Sophomore | 1112 (45.5) | 522 (41.7) | 590 (49. 5) |

As shown in Table 2, most medical and medical-related students had knowledge about AD, although the score of medical-related students was higher than that of medical students. In addition, 29.2% of students reported contact experience with AD patients, and there was no significant difference in specialty between the two groups. Among the 2444 students, 388 students had experience living with AD patients, although most had < 1 year of experience. Although the vast majority of surveyed students (86.7%) expressed interest and concerns regarding AD, only 35.4% were interested in becoming caregivers for AD patients (P < 0.05), and the proportion of medical students showing an interest was higher than that of medical-related students. This result is similar to that of a previous study, whereby although there was significant awareness of the AD situation, AD patients receiving caregiving services were limited[17].

| Variables | The total (n = 2444), n (%) | Medical major students (n = 1251), n (%) | Medical-related major students (n = 1193), n (%) | χ2 | P value | |

| Heard about Alzheimer’s disease | 8.466 | 0.004 | ||||

| Yes | 2179 (89.2) | 1093 (87.4) | 1086 (91.0) | |||

| No | 265 (10.8) | 158 (12.6) | 107 (9.0) | |||

| Interest and concern in Alzheimer’s disease | 31.469 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 2118 (86.7) | 1037 (82.9) | 1081 (90.7) | |||

| No | 326 (13.3) | 214 (17.1) | 112 (9.3) | |||

| Contact experience | 0.770 | 0.380 | ||||

| Yes | 714 (29.2) | 398 (31.8) | 316 (26.5) | |||

| No | 1730 (70.8) | 853 (68.2) | 877 (73.5) | |||

| First contact (n = 714) | 0.108 | 0.743 | ||||

| Before college | 263 (36.8) | 144 (36.2) | 119 (37.7) | |||

| At the time of college | 451 (63.2) | 254 (63.8) | 197 (62.3) | |||

| First place of contact (n = 714) | 0.117 | 0.732 | ||||

| House | 439 (61.5) | 242 (60.8) | 197 (62.3) | |||

| Other | 275 (38.5) | 156 (39.2) | 119 (37.7) | |||

| Experience living together | 3.175 | 0.075 | ||||

| Yes | 388 (54.3) | 204 (51.3) | 184 (58.2) | |||

| No | 326 (45.7) | 194 (48.7) | 132 (41.8) | |||

| Period of living together (n = 388) | 0.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| Less than 1 yr | 288 (74.2) | 151 (37.9) | 137 (43.4) | |||

| More than 1 yr | 100 (25.8) | 53 (62.1) | 47 (57.0) | |||

| Attitudes | 0.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| Positive | 2298 (94.0) | 1176 (94.0) | 1122 (94.0) | |||

| Negative | 146 (6.0) | 75 (6.0) | 71 (6.0) | |||

| Interested in participating in care | 16.336 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 864 (35.4) | 490 (39.2) | 374 (31.3) | |||

| No | 1580 (64.4) | 761 (60.8) | 819 (68.7) |

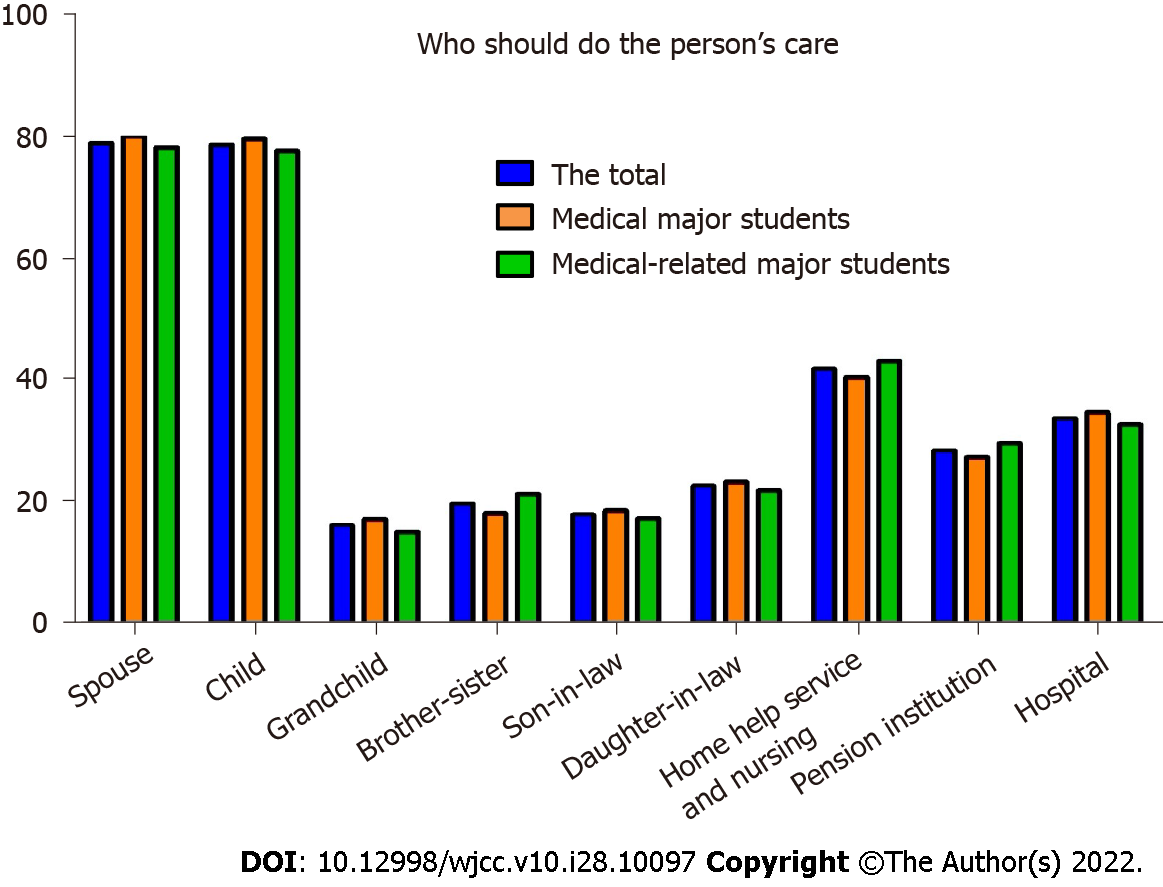

Because the course of AD is long, it is important to clarify the characteristics of a caregiver, especially those who care for patients during the middle-to-late stages of the disease. For the question of “Who should be a caregiver for an AD patient?”, spouses, children, and home healthcare/nursing services were considered as answers (Figure 1). The top three factors that influenced medical students’ knowledge about AD were mass media, newspapers/books, and college. In medical-related students, the top three factors were mass media, newspapers/books, and contact with AD patients (Figure 2).

What were the emotional characteristics of AD patients? The attitudes toward patients with AD encompassed 14 items, and a four-point scoring system was used as follows: Complete disagreement (score 1), disagreement (score 2), agreement (score 3), and complete agreement (score 4). The 14 items were classified into three categories: positive affective (four items; total score, 4-16 points; higher score indicates positive attitudes), negative affective (six items; total score, 6-24 points; higher score indicates negative attitudes), and external affective (four items; total score, 4-16 points; higher score indicates neutral attitudes). College students obtained average scores of 8.26 ± 2.53, 16.31 ± 2.79, and 8.57 ± 2.31 for positive, negative, and neutral attitudes, respectively (Table 3). The medical-vocational college students had more negative attitudes than medical students toward AD patients.

| Group | Total (n = 2444) | Medical major students (n = 1251) | Medical-related major students (n = 1193) | T value | P value |

| Positive affectivity | 8.26 ± 2.53 | 8.26 ± 2.43 | 8.27 ± 2.63 | 0.720 | 0.472 |

| Negative affectivity | 16.31 ± 2.79 | 16.35 ± 2.65 | 16.27 ± 2.93 | 3.597 | < 0.001 |

| External affectivity | 8.57 ± 2.31 | 8.73 ± 2.34 | 8.40 ± 2.27 | -0.082 | 0.935 |

The mean score of all students for dementia-related knowledge was 14.95 ± 2.21. The average score for knowledge about cognitively impaired older patients was 15.56 ± 1.87 in medical students and 13.19 ± 1.79 in medical-related students. For items 1, 10, 13, 14, 15, 16, and 17, which are related to the manifestations, care, and treatment of the disease, medical students had significantly higher knowledge than medical-related students. Several items in this scale were similar to those in the ADKS; therefore, we only explored the ADKS outcomes (Table 4). The mean total score for the ADKS was 21.16 ± 3.43. However, when medical students were excluded, the score dropped to 20.53 ± 2.84. The results of the statistical analysis showed that the risk factors and symptoms of AD had the lowest rate of errors (Table 5), which was inconsistent with previous reports[6]. There was a significant difference in the total score when analyzing the grade, AD-related knowledge, interest and concerns about AD, contact experience with AD patients, and attitudes toward and willingness to participate in the caregiving of AD patients (Table 6; P < 0.05). Overall, in comparison with other students, female sophomore students had a more positive attitude, a higher level of knowledge, more contact experience with AD patients, and a greater willingness to participate in the caregiving of AD patients. However, students’ interest and concerns about AD did not influence ADKS scores.

| Question | No. of correct answers, n (%) | ||

| Total (n = 2444) | Medical majors (n = 1251) | Medical-related majors (n = 1193) | |

| 1 People with Alzheimer’s disease are particularly prone to depression | 2136 (87. 4) | 1115 (89.1) | 1021 (85.6) |

| 2 It has been scientifically proven that mental exercise can prevent a person from getting Alzheimer’s disease | 987 (40.4) | 548 (43.8) | 439 (36.8) |

| 3 After symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease appear, the average life expectancy is 6 to 12 yr | 1677 (68.6) | 866 (69.2) | 811 (68.0) |

| 4 When a person with Alzheimer’s disease becomes agitated, a medical examination might reveal other health problems that caused the agitation | 1908 (78.1) | 981 (78.4) | 927 (77.7) |

| 5 People with Alzheimer’s disease do best with simple instructions given one step at a time | 1768 (72.3) | 961 (76.8) | 807 (67.6) |

| 6 When people with Alzheimer’s disease begin to have difficulty taking care of themselves, caregivers should take over right away | 1538 (62.9) | 845 (67.5) | 693 (58.1) |

| 7 If a person with Alzheimer’s disease becomes alert and agitated at night, a good strategy is to try to make sure that the person gets plenty of physical activity during the day | 1916 (78.4) | 968 (77.4) | 948 (79.5) |

| 8 In rare cases, people have recovered from Alzheimer’s disease | 1312 (53. 7) | 736 (58.8) | 576 (48.3) |

| 9 People whose Alzheimer’s disease is not yet severe can benefit from psychotherapy for depression and anxiety | 2208 (90.3) | 1149 (91.8) | 1059 (88.8) |

| 10 If trouble with memory and confused thinking appears suddenly, it is likely due to Alzheimer’s disease | 1589 (65.0) | 879 (70.3) | 710 (59.5) |

| 11 Most people with Alzheimer’s disease live in nursing homes | 1724 (70.5) | 900 (71.9) | 824 (69.1) |

| 12 Poor nutrition can make the symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease worse | 2051 (83.9) | 1059 (84. 7) | 992 (83.2) |

| 13 People in their 30s can have Alzheimer’s disease | 1546 (63.3) | 786 (62.8) | 760 (63.7) |

| 14 A person with Alzheimer’s disease becomes increasingly likely to fall down as the disease gets worse | 2245 (91.9) | 1164 (93.0) | 1081 (90.6) |

| 15 When people with Alzheimer’s disease repeat the same question or story several times, it is helpful to remind them that they are repeating themselves | 1561 (63.9) | 861 (68.8) | 700 (58.7) |

| 16 Once people have Alzheimer’s disease, they are no longer capable of making informed decisions about their own care | 1606 (65.7) | 840 (67.1) | 766 (64.2) |

| 17 Eventually, a person with Alzheimer’s disease will need 24 h supervision | 2065 (84.5) | 1079 (86.3) | 986 (82.6) |

| 18 Having high cholesterol may increase a person’s risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease | 1870 (76.5) | 951 (76.0) | 919 (77.0) |

| 19 Tremor or shaking of the hands or arms is a common symptom in people with Alzheimer’s disease | 1273 (52.1) | 717 (57.3) | 556 (46.6) |

| 20 Symptoms of severe depression can be mistaken for symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease | 1762 (72.1) | 942 (75.3) | 820 (68.7) |

| 21 Alzheimer’s disease is one type of dementia | 2173 (88.9) | 1114 (89.0) | 1059 (88.8) |

| 22 Trouble handling money or paying bills is a common early symptom of Alzheimer’s disease | 1649 (67.5) | 893 (71.4) | 756 (63.4) |

| 23 One symptom that can occur with Alzheimer’s disease is believing that other people are stealing one’s things | 1577 (64.5) | 848 (67.8) | 729 (61.1) |

| 24 When a person has Alzheimer’s disease, using reminder notes is a crutch that can contribute to decline | 1530 (62.6) | 855 (68.3) | 675 (56.6) |

| 25 Prescription drugs that prevent Alzheimer’s disease are available | 1336 (54.7) | 700 (56.0) | 636 (53.3) |

| 26 Having high blood pressure may increase a person’s risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease | 1948 (79.7) | 1002 (80.1) | 946 (79.3) |

| 27 Genes can only partially account for the development of Alzheimer’s disease | 1475 (60.4) | 685 (54.8) | 790 (66.2) |

| 28 It is safe for people with Alzheimer’s disease to drive, as long as they have a companion in the car at all times | 2064 (84.5) | 1053 (84. 2) | 1011 (84.7) |

| 29 Alzheimer’s disease cannot be cured | 1784 (73.0) | 951 (76.0) | 833 (69.8) |

| 30 Most people with Alzheimer’s disease remember recent events better than things that happened in the past | 1458 (59.7) | 798 (63.8) | 660 (55.3) |

| Variables | Range of total score | Total (n = 2444) | Medical-major students (n = 1251) | Medical-related major students (n = 1193) | Z/T value | P value |

| ADKS total | 0-30 | 21.16 ± 3.43 | 21.78 ± 3.81 | 20.53 ± 2.84 | -9.179 | < 0.001 |

| Risk factors | 0-6 | 3.75 ± 1.26 | 3.73 ± 1. 28 | 3.76 ± 1.28 | -0.026 | 0.979 |

| Assessment and diagnosis | 0-4 | 3.04 ± 0.91 | 3.13 ± 0. 95 | 2.95 ± 0.85 | -6.413 | < 0.001 |

| Symptoms | 0-4 | 2.44 ± 1.03 | 2.60 ± 0.99 | 2.26 ± 1.03 | -7.895 | < 0.001 |

| Course | 0-4 | 2.99 ± 0.89 | 3.07 ± 0.93 | 2.90 ± 0.84 | -6.088 | < 0.001 |

| Caregiving | 0-5 | 3.43 ± 1.17 | 3.58 ± 1.21 | 3.28 ± 1.10 | -6.434 | < 0.001 |

| Treatment and management | 0-4 | 3.10 ± 0.80 | 3.21 ± 0.83 | 2.98 ± 0.75 | -8.266 | < 0.001 |

| Life impact | 0-3 | 2. 42 ± 0. 70 | 2. 45 ± 0. 69 | 2. 39 ± 0. 71 | -2.100 | 0.979 |

| Variables | ADKS | Z/T value | P value | |

| Grade | -6.320 | < 0.001 | ||

| Freshman | 20.73 ± 3.33 | |||

| Sophomore | 21.69 ± 3.48 | |||

| Sex | -2.281 | 0.023 | ||

| Female | 21.29 ± 3.51 | |||

| Male | 20.97 ± 3.29 | |||

| Heard about AD | -3.073 | 0.002 | ||

| Yes | 22.08 ± 3.98 | |||

| No | 21.06 ± 3.34 | |||

| Interest and concern in AD | -0.544 | 0.586 | ||

| Yes | 21.40 ± 4.10 | |||

| No | 21.13 ± 3.32 | |||

| Contact experienced | -6.227 | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 21.97 ± 3.64 | |||

| No | 20.81 ± 3.28 | |||

| Attitudes | -4.948 | < 0.001 | ||

| Positive | 21.84 ± 3.64 | |||

| Negative | 20.74 ± 3.28 | |||

| Interested in participating in care | -3.097 | 0.002 | ||

| Yes | 21.47 ± 3.25 | |||

| No | 21.00 ± 3.52 |

According to the Seventh National Population Census, the population of Anhui province is approximately 61 million, and the proportions of older adults aged ≥ 60 and ≥ 65 years are 18.79% and 15.01%, respectively, which are higher than those in China (18.70% and 13.50%, respectively). Older age has been shown to increase the risk of dementia. Indeed, in Chinese societies, the prevalence rate of dementia for people aged 60 years and above is 7.7%[18]. Although the progression of dementia is irreversible, professional healthcare has positive effects on delaying the progression of dementia. Thus, diagnosis and therapy during the early stage of dementia significantly influence the progression of dementia. Families provide a comfortable environment for AD patients, where the patients have a sense of familiarity with the surroundings and caregivers. However, most traditional family care services are focused on meeting patients’ physiologic needs, and the lack of professional healthcare services negatively affects the disease course and quality of life of AD patients. The Sixth National Health Service Survey in China revealed that 87.1% of patients visited clinics within the county, and over 90% of rural residents received medical treatment in county medical institutions. Studies have demonstrated that primary medical institutions provide the best medical support for the family of dementia patients[19]. Therefore, research needs to focus on families and communities to develop effective diagnostic and therapeutic approaches during the early stage of dementia, which may include non-pharmacological interventions and high-quality in-home healthcare services.

Because medical students will be in charge of providing medical services during their careers, they must be guided to ensure they obtain the correct knowledge and attitudes. We found that among 2444 students, 2179 (89.2%) students were knowledgeable about AD. The proportions of medical-related students who had knowledge of and were interested in AD were 91.0% and 90.7%, respectively, which was higher than those of medical students. Theoretically, medical students would have more specialized knowledge than medical-related students. However, because the course on AD had not been launched in the eight colleges before the survey, neither medical nor medical-related students had specialized knowledge about AD. Furthermore, the discrepancies in the above proportions may be influenced by various factors, such as experience and interest. In addition, the results indicated that students who had more knowledge had more interest and concerns regarding dementia, which suggests that a specialized course in AD is necessary for medical-vocational college students to effectively develop their concerns and alter their negative attitudes toward dementia patients. Only 29.2% of students responded “yes” to the item of “contact experience with AD patients”. This may be attributed to the following reasons: patients were not diagnosed by formal healthcare facilities; patients and their families failed to identify the typical dementia syndrome; the symptoms of early-stage dementia are considered a phenomenon of aging (even by those who with experience with AD patients and general practitioners)[5,6]. Moreover, in China, there is a stigma attached to the term “dementia,” and family members of dementia patients often prefer not to share that their family has dementia with friends. There were several puzzling results of our survey. Although 2118 students showed interest and concern for AD, only 35.4% of students responded “yes” to the item of “willingness to participate in caregiving of AD patients,” and the proportion was higher in medical students than in medical-related students. This result is inconsistent with previous findings. In 2008, a survey of people aged > 40 years showed a positive correlation between knowledge about AD and willingness to provide caregiving services to AD patients[20]. People with more AD-related knowledge can prepare AD patients and their family members for the challenges they may encounter. In both medical and medical-related students, attitudes towards AD were predominantly negative, and the subgroup analysis showed that medical students obtained higher scores in the negative affective category than medical-related students. A positive attitude will likely facilitate the strengthening of the knowledge and skills related to dementia care[5]. However, our results indicated that with increasing knowledge about dementia, the willingness of students to care for AD patients decreased. We speculated that this may be related to the difficulties in the processes of caregiving for dementia patients. When analyzing factors that may influence ADKS scores, we found that female sophomore students obtained higher scores and had received more opportunities to acquire knowledge about AD via dementia-related medical-vocational programs than medical-related students.

The primary objective of the present study was to improve knowledge about AD in both medical and medical-related students in the future. When responding to the question, “Who can care for an AD patient?”, all students selected spouses as the first choice, indicating that people prefer to be cared for by their closest family members. However, because of the difficulties of caregiving, sending AD patients to hospital or providing in-home healthcare/nursing services may be considered an alternative option. We found that 79.1% of students chose “mass media” as the most influential factor that affected their dementia-related knowledge, which is likely attributed to the penetration rate of electronic media. This may be a basis for promoting AD-related knowledge in the future.

Han et al[21] demonstrated that timely diagnosis in the community enables patients to receive community-based interventions, whereby patients with cognitive impairment are cared for by their family. This significantly enhances the capacity of care, improves patients’ quality of life, and decreases the negative physical and psychological burdens on caregivers. In some counties, patients or those with suspected dementia are diagnosed in primary care settings[22] and referred to specialists for further treatment. However, the implementation of such primary care services is not currently feasible in China[5]. An older adult care hospital in Chengdu (China) has made significant progress in providing care for older patients with cognitive impairment via the establishment of a “Five-Element Model,” which comprises five items: older adult medical care, older adult care, geriatric rehabilitation, training of healthcare workers, and health-related problems of older adults. Taken together, these results confirm that further professional primary healthcare practitioners should contribute to the diagnosis and treatment of dementia[23]. In our study, life impact, treatment and management, and assessment and diagnosis were found as the most influential domains. Risk factors and symptoms had fewer correct answers compared with the others; one of the questions relating to risk factors obtained a correct response rate of only 36.8% (“it has been scientifically proven that regular exercise is useful in pre

Several limitations of our study should be noted. The main limitation was that the students were recruited from only one province. Moreover, because of the coronavirus 2019 disease pandemic, there were several travel-based restrictions. In addition, the ADKS-based questionnaire comprised only true or false responses, which increased the probability that students guessed the answers to the multiple-choice questions. Therefore, the correct response rate may not be accurate. The addition of a third or fourth option (i.e., “I don’t know” or “I’m not sure”) could be considered in future studies. Because the course in AD had not been launched in the eight colleges before the survey, we believe that the level of the course may have influenced the results of the survey. However, we also considered that the differences in courses among colleges, the study abilities among students, and the various majors would have an impact on the results. Thus, these factors should be included in future studies.

The present study examined the contact experience with AD patients, attitudes, and the level of dementia-related knowledge in medical-vocational college students who will work primarily in primary healthcare systems following graduation. More than half of the medical-vocational college students had knowledge of AD, less than one-third had contact experience with AD patients, and most had negative attitudes towards dementia patients. Additionally, few students showed a high willingness to participate in the caregiving of AD patients, and their level of knowledge about dementia was low. In summary, further resources should be provided in medical-vocational colleges to promote dementia literacy, in terms of not only dementia-related knowledge but also the emotional features of dementia patients.

Resources about Alzheimer’s disease (AD) should be provided to promote dementia literacy in medical vocational colleges.

The dementia-related knowledge and their overall attitude toward dementia should be improved among medical vocational college students.

Student's willingness of care-giving intentions for AD is low. Students hold negative attitudes in dementia patients.

We performed a questionnaire survey among medical vocational college students.

To study level of knowledge, contact experience and attitude of dementia among the medical vocational college students in China.

The knowledge and attitude of medical vocational college students are important for supporting primary healthcare systems.

Dementia is a severe healthy issue worldwide. The knowledge and attitudes of the general publics for dementia patients is important for the caregiving of patients.

We thank the people who provided critical mentoring and advice. The efforts of the participating students, staff of the colleges, and our team members are highly appreciated.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Nursing

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Brkanović S, Croatia; de Melo FF, Brazil S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: A P-Editor: Yan JP

| 1. | Blomstedt GC. Infections in neurosurgery: a retrospective study of 1143 patients and 1517 operations. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1985;78:81-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Huang Y, Wang Y, Wang H, Liu Z, Yu X, Yan J, Yu Y, Kou C, Xu X, Lu J, Wang Z, He S, Xu Y, He Y, Li T, Guo W, Tian H, Xu G, Ma Y, Wang L, Yan Y, Wang B, Xiao S, Zhou L, Li L, Tan L, Zhang T, Ma C, Li Q, Ding H, Geng H, Jia F, Shi J, Wang S, Zhang N, Du X, Wu Y. Prevalence of mental disorders in China: a cross-sectional epidemiological study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6:211-224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1590] [Cited by in RCA: 1339] [Article Influence: 223.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Black CM, Fillit H, Xie L, Hu X, Kariburyo MF, Ambegaonkar BM, Baser O, Yuce H, Khandker RK. Economic Burden, Mortality, and Institutionalization in Patients Newly Diagnosed with Alzheimer's Disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;61:185-193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Michalowsky B, Xie F, Eichler T, Hertel J, Kaczynski A, Kilimann I, Teipel S, Wucherer D, Zwingmann I, Thyrian JR, Hoffmann W. Cost-effectiveness of a collaborative dementia care management-Results of a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Alzheimers Dement. 2019;15:1296-1308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Wang M, Xu X, Huang Y, Shao S, Chen X, Li J, Du J. Knowledge, attitudes and skills of dementia care in general practice: a cross-sectional study in primary health settings in Beijing, China. BMC Fam Pract. 2020;21:89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Amado DK, Brucki SMD. Knowledge about Alzheimer's disease in the Brazilian population. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2018;76:775-782. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Zhao W, Moyle W, Wu MW, Petsky H. Hospital healthcare professionals' knowledge of dementia and attitudes towards dementia care: A cross-sectional study. J Clin Nurs. 2022;31:1786-1799. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Yang HF, Cong JY, Zang XY, Jiang N, Zhao Y. A study on knowledge, attitudes and health behaviours regarding Alzheimer's disease among community residents in Tianjin, China. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2015;22:706-714. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Eichler T, Thyrian JR, Hertel J, Köhler L, Wucherer D, Dreier A, Michalowsky B, Teipel S, Hoffmann W. Rates of formal diagnosis in people screened positive for dementia in primary care: results of the DelpHi-Trial. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;42:451-458. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Manu ER, Fitzgerald JT, Mullan PB, Vitale CA. Eating Problems in Advanced Dementia: Navigating Difficult Conversations. MedEdPORTAL. 2020;16:11025. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | van der Steen JT, Lennaerts H, Hommel D, Augustijn B, Groot M, Hasselaar J, Bloem BR, Koopmans RTCM. Dementia and Parkinson's Disease: Similar and Divergent Challenges in Providing Palliative Care. Front Neurol. 2019;10:54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Scerri A, Scerri C. Nursing students' knowledge and attitudes towards dementia - a questionnaire survey. Nurse Educ Today. 2013;33:962-968. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 13. | Shadid AM, Aldayel AY, Shadid A, Alqaraishi AM, Gholah MM, Almughiseeb FA, Alessa YA, Alani HF, Khan SUD, Algarni S. Extent of and influences on knowledge of Alzheimer's disease among undergraduate medical students. J Family Med Prim Care. 2020;9:3707-3711. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wang Y, Xiao LD, Huang R. A comparative study of dementia knowledge, attitudes and care approach among Chinese nursing and medical students. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20:436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Rohlfing J, Navarro R, Maniya OZ, Hughes BD, Rogalsky DK. Medical student debt and major life choices other than specialty. Med Educ Online. 2014;19:25603. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Zhao Y, Eccleston CE, Ding Y, Shan Y, Liu L, Chan HYL. Validation of a Chinese version of the dementia knowledge assessment scale in healthcare providers in China. J Clin Nurs. 2022;31:1776-1785. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Tabana H, Dudley LD, Knight S, Cameron N, Mahomed H, Goliath C, Eggers R, Wiysonge CS. The acceptability of three vaccine injections given to infants during a single clinic visit in South Africa. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:749. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ji Y, Shi Z, Zhang Y, Liu S, Yue W, Liu M, Huo YR, Wang J, Wisniewski T. Prevalence of dementia and main subtypes in rural northern China. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2015;39:294-302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Zhang L, Zeng Y, Wang L, Fang Y. Urban-Rural Differences in Long-Term Care Service Status and Needs Among Home-Based Elderly People in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Arai A, Arai Y. [Advance care planning among the general public in Japan: association with awareness about dementia]. Nihon Ronen Igakkai Zasshi. 2008;45:640-646. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Han HR, Choi S, Wang J, Lee HB. Pilot testing of a dementia literacy intervention for Korean American elders with dementia and their caregivers. J Clin Transl Res. 2021;7:712-716. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Wilcock J, Iliffe S, Turner S, Bryans M, O'Carroll R, Keady J, Levin E, Downs M. Concordance with clinical practice guidelines for dementia in general practice. Aging Ment Health. 2009;13:155-161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Thyrian JR, Hertel J, Wucherer D, Eichler T, Michalowsky B, Dreier-Wolfgramm A, Zwingmann I, Kilimann I, Teipel S, Hoffmann W. Effectiveness and Safety of Dementia Care Management in Primary Care: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74:996-1004. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |