Published online Oct 6, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i28.10066

Peer-review started: June 7, 2022

First decision: July 12, 2022

Revised: July 26, 2022

Accepted: August 17, 2022

Article in press: August 17, 2022

Published online: October 6, 2022

Processing time: 112 Days and 8.1 Hours

The 5-fluorouracil-based chemotherapy combined with oxaliplatin or irinotecan is usually used in colorectal cancer (CRC). The addition of a targeted agent (TA) to this combination chemotherapy is currently the standard treatment for metastatic CRC. However, the efficacy and safety of combination chemotherapy for meta

To assess the clinical outcomes and feasibility of combination chemotherapy using a TA in extremely elderly patients with CRC.

Eligibility criteria were: (1) Age above 80 years; (2) Metastatic colorectal cancer; (3) Palliative chemotherapy naïve; (4) Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status 0-1; and (5) Adequate organ function. Patients received at least one dose of combination chemotherapy with or without TA. Response was evaluated every 8 wk.

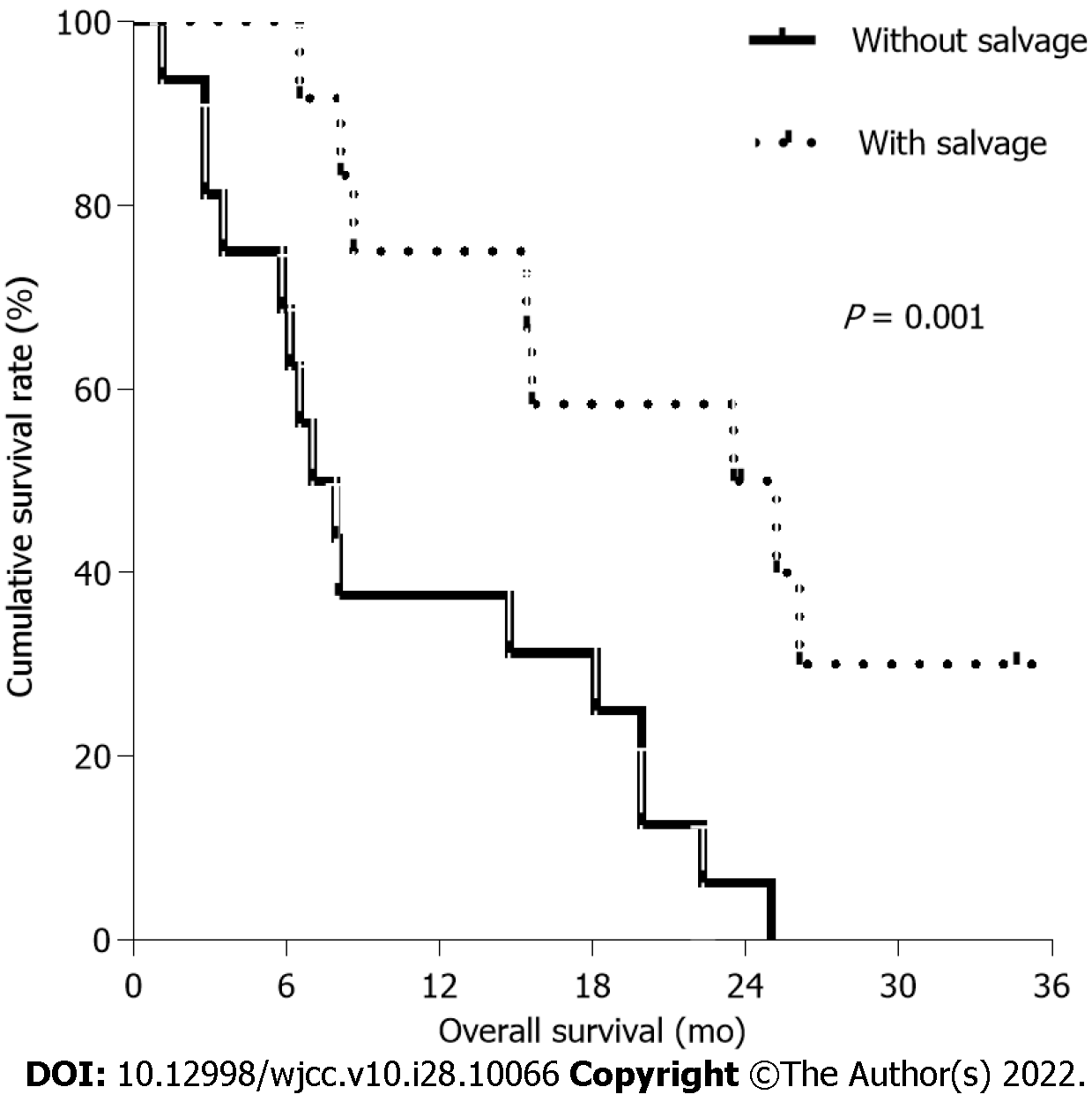

Of 30 patients, the median age of 15 patients treated with TA was 83.0 years and that of those without TA was 81.3 years. The median progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) in patients treated with TA were 7.4 mo and 15.4 mo, respectively, compared with 4.4 mo and 15.6 mo, respectively, in patients treated without TA. There was no significant difference in PFS (P: 0.193) and OS (P: 0.748) between patients treated with and without TA. Common grade 3/4 hematologic toxicities were anemia (16.7%) and neutropenia (10.0%). After disease progression, the median OS of patients who were treated with and without salvage chemotherapy were 23.5 mo and 7.0 mo, respectively, suggesting significant difference in OS (P = 0.001).

Combination chemotherapy with TA for metastatic CRC may be considered feasible in patients aged above 80 years, when with careful caution. Salvage chemotherapy can help improve OS in some selected of these elderly patients.

Core Tip:This study assessed the clinical outcomes of combination chemotherapy and feasibility of target agent (TA) in extremely elderly patients (defined as ≥ 80 years of age) with for metastatic colorectal cancer. The median progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) in patients treated with TA were 7.4 mo and 15.4 mo, respectively, compared with 4.4 mo and 15.6 mo, respectively, in patients treated without TA. There was no significant difference in PFS (P: 0.193) and OS (P: 0.748) rates. Targeted therapies may be considered with careful caution even in elderly patients. After disease progression, salvage chemotherapy may help improve OS in some selected of these elderly patients.

- Citation: Jang HR, Lee HY, Song SY, Lim KH. Clinical outcomes of targeted therapies in elderly patients aged ≥ 80 years with metastatic colorectal cancer. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(28): 10066-10076

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i28/10066.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i28.10066

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the most common gastrointestinal malignancy, and considered as elderly disease due to the large proportion of patients above 65 years of age[1-3]. The United States Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results cancer registry reported that 50% of diagnosed cases with CRC were in patients aged above 65 years. During the most recent 5 years (2012-2016), the annual age-standardized CRC incidence rate was 38.7 per 100000 and the incidence rate increased with age. The rate increased from 237.9 per 100000 populations in the extremely elderly group, aged above 80 years[2]. In spite of a gradual improvement in clinical outcomes probably due to early detection and effective treatment, the overall survival (OS) of elderly patients with CRC is still low. The definition of an elderly patient varies according to socioeconomic situations. In many clinical trials, the geriatric age is typically 65 to 70 years or older. Elderly patients are often undertreated or require dose reduction due to comorbidities, cognitive impairment, drug pharmacokinetics, potential tolerance to treatment and issues of family/social support. For these reasons, elderly patients have been under-represented or excluded from clinical trials because of strict inclusion criteria, precluding meaningful conclusions about the efficacy and safety of chemotherapy in this age subgroup[4-6].

Fluorouracil (FU)/leucovorin (LV) was the sole active regimen used traditionally for metastatic CRC with a median OS of approximately 8 to 9 mo[7]. The advent of irinotecan and oxaliplatin has changed the treatment of CRC since the year 2000. Two combination regimens of FU/LV and irinotecan (FOLFIRI) or FU/LV and oxaliplatin (FOLFOX) were superior to FU/LV alone and showed similar efficacy with a median survival of 18 to 20 mo[8-11]. FOLFOX or FOLRIRI is the standard treatment regimen in metastatic CRC. Bevacizumab and cetuximab are the most commonly used biological targeted agents (TA). Bevacizumab is a monoclonal antibody binding to the vascular endothelial growth factor and exhibiting antiangiogenic properties[12]. In the pivotal Avastin/Fluorouracil 2107 phase III trial, patients with metastatic colorectal cancer were randomized to irinotecan, bolus fluorouracil, and leucovorin (IFL) with bevacizumab or IFL alone, and the addition of bevacizumab to IFL was superior to IFL alone, in terms of OS, progression-free survival (PFS) and overall response rate (ORR)[13]. Another pivotal phase 3 NO16966 showed an incremental improvement in PFS with the addition of bevacizumab to oxaliplatin-containing regimen[14]. In the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group study E3200 and Bevacizumab Regimens: Investigation of Treatment Effects and Safety (BRiTE) registry, the PFS and OS benefit of continuing with bevacizumab beyond first-line progression was demonstrated[15,16]. Cetuximab is another TA, which is a recombinant chimeric monoclonal antibody binding specifically to the epidermal growth factor receptor and is indicated for patients with wild-type RAS tumors. In two phase 3 trial, the OS, PFS and ORR of patients treated with FOLFIRI or FOLFOX and cetuximab were better than those of patients treated with only FOLFIRI or FOLFOX[17,18]. Accordingly, the addition of TA to combination chemotherapy is currently recognized as a standard first- and second-line chemotherapy[19].

Palliative chemotherapy including FOLFOX or FOLFIRI is active and safe against metastatic CRC in elderly patients compared with younger patients[20-24]. However, few studies investigated the benefit of TA addition in these patient groups as well the feasibility of combination chemotherapy provided to elderly patients aged above 80 years. Thus, this study assessed the clinical outcomes of combination chemotherapy and feasibility of TA (bevacizumab or cetuximab) in extremely elderly patients (defined as ≥ age 80) with metastatic CRC.

The study population consisted of consecutive elderly patients who were treated with combination chemotherapy for metastatic CRC at Kangwon National University Hospital in South Korea from January 2010 to September 2019. The eligibility criteria were: age ≥ 80 years; histologically proven metastatic CRC; no previous palliative chemotherapy for metastatic CRC; 5-fluorouracil (5-FU)-based combination chemotherapy; Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS) of 0-1; and adequate bone marrow, liver and renal function. Medical records were retrospectively reviewed, including patients’ demographic characteristics, surgeries, pathology reports showing genetic mutations, chemotherapy regimens, treatment responses, toxicity profiles, and comorbidity. The exclusion criteria were: histological findings indicating a condition other than adenocarcinoma; first-line palliative chemotherapy with a single agent; severe concomitant medical diseases; and a history of other malignancies. Informed consent for chemotherapy was obtained from all patients. The study was performed in full accordance with the precepts of the Declaration of Helsinki. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Kangwon National University Hospital (IRB No: KNUH-2021-03-008).

Treatment schedules for metastatic CRC were based on modified FOLFOX or FOLFIRI regimens. The modified FOLFOX regimen included oxaliplatin treatment at a dose of 85 mg/m2 over 2 h on day 1, administering LV at 400 mg/m2 over 2 h, 5-FU at 400 mg/m2 intravenously, and 2400 mg/m2 over 46 h on day 1. Modified FOLFIRI regimen included irinotecan (180 mg/m2 over 2 h) instead of oxaliplatin on day 1. The TAs were either bevacizumab or cetuximab, one of which was added to FOLFOX or FOLFIRI. On day 1, the dose of bevacizumab was fixed at 5 mg/kg for every cycle, and the dose of cetuximab was fixed at 500 mg/m2 for every cycle on day 1. Treatment was continued every 2 wk until disease progression, unacceptable toxicity or patient refusal. Response evaluation was performed using computed tomography every 4 cycles in each chemotherapy protocol and assessed according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors guidelines.

Before each cycle of chemotherapy, hematological and non-hematological toxicities were assessed. Dose modifications and administration delays were based on adverse effects graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events. In the event of grade 3-4 hematologic toxicity, the schedule was delayed until hematologic recovery and the doses of the next cycle were reduced by 25%. Our study team decided to discontinue consecutive chemotherapy if the patient experienced an objective decline in ECOG PS.

The following treatment outcomes were evaluated according to the use of target agents: PFS, OS, 1-year survival rate, ORR and toxic profiles. PFS was defined as the time elapsed from the starting day of treatment to the day of disease progression or death from any cause. OS was defined as the time elapsed from the first day of study to the final day of follow-up or death from any cause. Distributions of the discrete variables were compared between the different groups using either the Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. PFS and OS were determined using Kaplan-Meier method, and survival differences were analyzed using the log-rank test. All tests were two-sided and p < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS software version 23 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Thirty consecutive patients who fulfilled the inclusion criteria were retrospectively reviewed January 2010-September 2019. According to the use of TA, there were 15 patients in both groups. The baseline characteristics of these patients are listed in Table 1. The median age was 83.0 years in patients treated with TA and 81.3 years in patients without TA. The male-to-female ratio in patients with TA was 5:10 compared with 10:5 in patients without TA. All patients had a PS of 1 except for one patient with a PS of 0. The location of the primary tumor was the left colon (n: 17, 56.7%) and rectum (n: 5, 16.7%) in this study. Eight patients with TA (53.3%) and 6 patients without TA (40.0%) underwent curative resection of primary tumor. Adjuvant chemotherapy with 5-FU-based regimens was administered to 5 patients (62.5%) with TA and 2 patients (33.4%) without TA. The study population presented with diverse comorbidities, with hypertension (53.3%) being the most common, followed by diabetes mellitus (23.3%). Bevacizumab (n: 12, 80%) and cetuximab (n: 3, 20%) were used in patients with TA. Liver was the most frequent metastatic site in both groups, followed by peritoneum and lung. At the time of this analysis, 26 patients (86.7%) were deceased and 4 patients (13.3%) were alive.

| Group with TA (n: 15) | Group without TA (n: 15) | |

| Median age, years (range) | 83.0 (80.2-89.6) | 81.3 (80.0-89.3) |

| Sex, % | ||

| Male | 5 (33.3) | 10 (66.7) |

| Female | 10 (66.7) | 5 (33.3) |

| Comorbidity, %1 | ||

| Hypertension | 8 (57.1) | 9 (64.3) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 4 (28.6) | 2 (14.3) |

| Cardiac valve disease | 5 (35.7) | 2 (14.3) |

| Pulmonary embolism | 1 (7.1) | 4 (28.6) |

| Ischemic heart disease | 1 (7.1) | 3 (21.4) |

| Primary location of tumor, % | ||

| Right colon | 9 (64.3) | 10 (71.4) |

| Transverse colon | 2 (14.3) | 4 (28.6) |

| Left colon | 1 (7.1) | 0 |

| Rectum | 1 (7.1) | 0 |

| Metastatic site, %1 | ||

| Liver | 8 (53.3) | 10 (66.7) |

| Peritoneum | 6 (40.0) | 5 (33.3) |

| Lung | 5 (33.3) | 5 (33.3) |

| Distant LN | 4 (26.7) | 2 (12.5) |

| Bone | 4 (26.7) | 2 (12.5) |

| Others | 1 (6.7) | 1 (6.7) |

| Surgery | ||

| Curative | 8 (53.3) | 6 (40.0) |

| Palliative | 3 (20.0) | 2 (13.3) |

| None | 4 (26.7) | 7 (46.7) |

| No. of metastases | ||

| 1 | 5 (33.3%) | 10 (66.7%) |

| 2 | 8 (53.3%) | 2 (13.3%) |

| ≥ 3 | 2 (13.3%) | 3 (20.0%) |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | ||

| Yes | 5 (62.5) | 2 (33.3) |

| No | 3 (37.5) | 4 (66.7) |

| 1st line chemotherapy regimen | ||

| FOLFOX | 9 (60.0) | 15 (100) |

| FOLFIRI | 6 (40.0) | 0 |

All patients received more than one cycle of first-line combination chemotherapy with or without TA. Patients treated with TA received a total of 137 cycles as first-line treatment and those without TA a total of 109 cycles. The median number of cycles per patient was 6 (range, 2-27) with TA and 4 (range 1-12) without TA. Initial dose reduction of chemotherapy was performed in 13 out of 15 patients (86.7%) with TA compared with 2 out of 15 patients (13.3%) treated without TA. The intravenous bolus of 5-FU was omitted in 21 (70.0%) of 30 patients. Additional dose reduction or delay due to treatment-related toxicity occurred in 7 patients (46.7%) treated with TA and 9 patients (60.0%) without TA. More than 10 cycles of first-line treatment were administered to 6 patients (40.0%) treated with TA and 7 patients (46.7%) without TA. The maximal cycles of FOLFOX with/without TA were 12 in 3 patients (37.5%) with TA and 7 patients (46.7%) without TA. The maximum number of cycles was 27 in one patient who received bevacizumab and FOLFIRI.

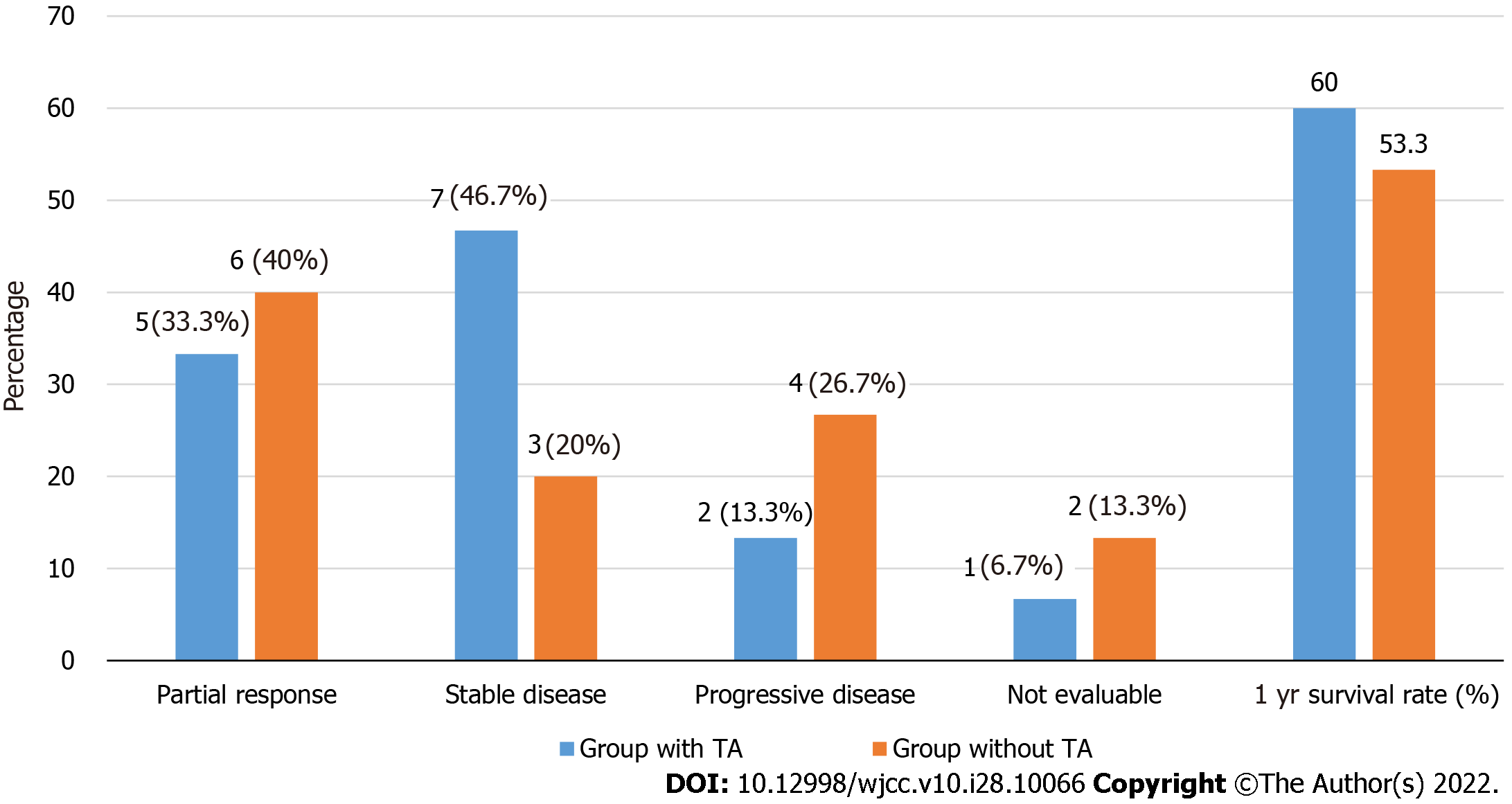

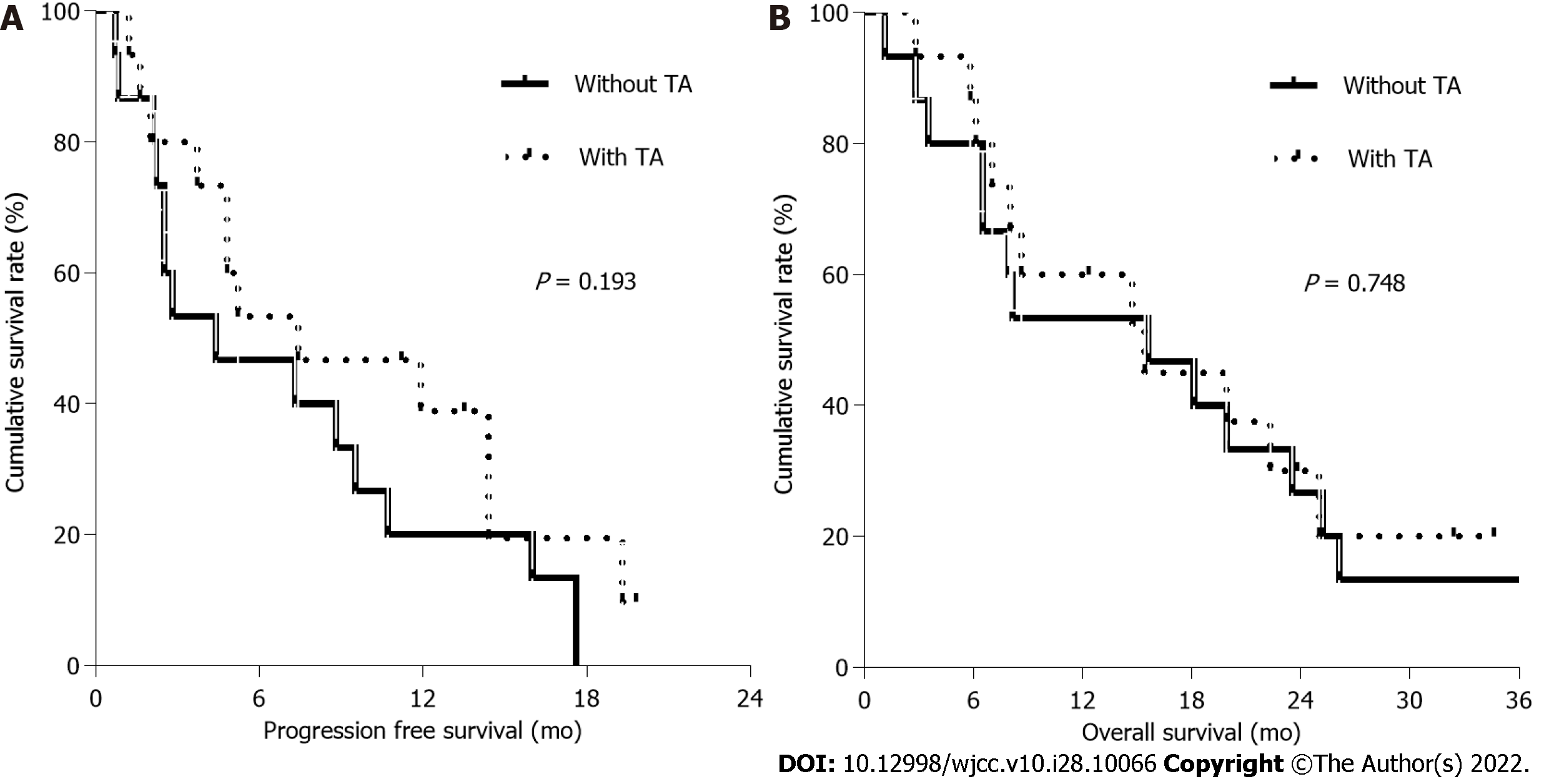

Among 30 patients, the response was evaluated in 14 patients treated with TA and 13 patients without TA, respectively (Figure 1). The median PFS and OS were 5.2 mo and 15.4 mo, respectively, with an ORR of 40.7%. Five patients (33.3%) in patients with TA had partial response (PR) with a disease control rate (DCR) of 80.0% and 6 patients (40.0%) without TA showed a PR with a DCR of 60.0%. Median PFS in patients with and without TA was 7.4 mo (95%CI, 0.0-15.9 mo) and 4.4 mo (95%CI, 0.0-10.5 mo), respectively (Figure 2A). Median OS in patients with and without TA were 15.4 mo (95%CI, 3.7-27.1 mo) and 15.6 mo (95%CI, 2.7-28.5 mo), respectively (Figure 2B). The 1-year survival rate was 60.0% in patients with TA and 53.3% in patients without TA. There was no significant difference in PFS (P: 0.193) and OS (P: 0.748) between patients with and without TA. After receiving first-line chemotherapy 16 patients (53.3%) stopped further treatment. These patients included 9 patients who were treated with TA and 7 patients without TA. No salvage chemotherapy was administered to these elderly patients mainly because of decreased PS due to disease progression (n: 6, 37.5%), patient’s intolerance (n: 4, 25.0%) and refusal to undergo further treatment (n: 4, 25.0%).

Treatment-related hematological and non-hematological toxicities are shown in Table 2. Grade 3-4 hematological toxicities consisting of anemia (16.7%), neutropenia (10.0%) and thrombocytopenia (3.3%) were observed in 9 of 30 patients (30.0%) including 4 patients with TA and 5 patients without TA. Grade 4 neutropenia was reported in one patient, who showed spontaneous recovery without complication. The most common non-hematological toxicity was anorexia involving 8 patients with TA (53.3%) and 7 patients without TA (46.7%). Grade 3 oxaliplatin-induced neuropathy was observed in only one patient, who received a cumulative dose of oxaliplatin of 1,020 mg/m2. Out of 12 patients with bevacizumab grade 1-2 hypertension occurred in 3 patients, one of whom had cerebral infarction. Two of 3 patients who received cetuximab developed Grade 1-2 acne. One patient showed hypersensitivity to cetuximab and received bevacizumab from the next cycle. There was no treatment-related death in this study.

| Toxicity | Group treated with TA | Group treated without TA | ||

| Grade 1-2, % | Grade 3-4, % | Grade 1-2, % | Grade 3-4, % | |

| Hematologic toxicity | ||||

| Neutropenia | 2 (13.3) | 2 (13.3) | 5 (33.3) | 3 (20.0) |

| Anemia | 3 (20.0) | 2 (13.3) | 4 (26.7) | 1 (6.7) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 0 | 0 | 5 (33.3) | 1 (6.7) |

| Non-hematologic toxicity | ||||

| Nausea/vomiting | 5 (33.3) | 2 (13.3) | 3 (20.0) | 2 (13.3) |

| Oral mucositis | 6 (40.0) | 1 (6.7) | 2 (13.3) | 0 |

| Anorexia | 8 (53.3) | 0 | 7 (46.7) | 0 |

| Neuropathy | 4 (28.5) | 1 (6.7) | 8 (57.1) | 0 |

| Diarrhea | 2 (13.3) | 1 (6.7) | 3 (20.0) | 1 (6.7) |

Of 30 patients, 12 patients (40%) underwent salvage chemotherapy. Two patients who received TA interrupted first-line chemotherapy and were followed up regularly without disease progression (Table 3). After first-line treatment failure, 4 patients treated with TA (30.8%) underwent second-line treatment and three of them received combination chemotherapy, which included bevacizumab. Eight patients without TA (53.3%) were treated with cytotoxic chemotherapy alone as the second-line treatment. Third-line chemotherapy was provided to 5 patients (16.7%), 4 of whom received cape

| Group with TA (n: 15) | Group without TA (n: 15) | ||

| 2nd line chemotherapy, % | |||

| Yes | 4 (26.7) | 8 (53.3) | |

| No | 11 (73.3)1 | 7 (46.7) | |

| 2nd line chemotherapy agents, % | |||

| FOLFOX | 3 (75.0) | 0 | |

| FOLFIRI | 0 | 6 (75.0) | |

| Capecitabine | 1 (25.0) | 2 (25.0) | |

| No of chemotherapy line, % | |||

| 1st line | 11* (73.3) | 7 (46.7) | |

| 2nd line | 2 (13.3) | 5 (31.3) | |

| 3rd line | 2 (13.3) | 3 (20.0) |

This study showed that combination chemotherapy may be feasible in extremely elderly patients with metastatic CRC and may be effective in some of these patients. Addition of TA to combination chemotherapy did not increase clinically significant toxicity, and although it was not statistically significant, it showed some tendency to increase PFS. After the failure of first-line chemotherapy, salvage chemotherapy patients showed the possibility of survival benefit in some of these elderly.

In this study, the results of the group without TA were relatively consistent with previous findings. In a randomized study of elderly patients with metastatic CRC including 13% older than age 80, the median PFS and OS were 5.8 and 10.7 mo, respectively[25]. In another study of elderly patients (age 76-80) with metastatic CRC, modified FOLFOX regimens showed median PFS and OS of 9.0 mo and 20.7 mo, respectively, with an ORR of 59.4%[24].

Several studies combining TA with cytotoxic chemotherapy in older patients with metastatic CRC have been reported recently. The BEAT and BRiTE studies reported similar OS: 16.6 mo in patients age ≥ 75 in the BEAT study and 16.2 mo in patients age 80 in the BRiTE study[26,27]. In the phase III study of capecitabine alone or combined with bevacizumab in patients with CRC aged above 70 years, the addition of bevacizumab improved PFS (9.1 vs 5.1 mo) than capecitabine alone, but no OS differences were found between both arms[28]. In another study investigating the combination of bevacizumab with a single agent, the addition of bevacizumab in patients aged 75 years or older was associated with longer PFS (8.8 vs 5.8 mo), but there was no significant difference in OS[29]. In the PRODIGE 20 trial, no significant differences were found in PFS (9.7 vs 7.8 mo) and OS (21.7 vs 19.8 mo)[30]. A pooled analysis of the efficacy of cetuximab in combination with FOLFOX and FOLFIRI revealed that the addition of cetuximab did not improved PFS (8.9 vs 7.2 mo, P: 0.78), OS (23.3 vs 15.1 mo, P: 0.38) and response rate (50.0 vs 38.8%, P: 0.23) in patients older than 70 years, compared with chemotherapy alone[31]. In our study, as in these studies, there were no statistically significant differences between PFS and OS.

Since safety played a significant role in treatment decisions, chemotherapy-related toxicity should be considered very important, especially in elderly patients over 80 years of age. Several studies investigating FOLFOX revealed that elderly patients with CRC exhibited higher levels of neutropenia (40%-49%) and peripheral neuropathy (12-22%) of grade 3-4 toxicity than younger patients, even if adverse events were manageable and no life-threatening events occurred[23,24]. It has been reported that continuous administration of 5-FU was better than a bolus of 5-FU in terms of efficacy and toxicity in patients with CRC[32]. A significant number of patients in this study did not receive a 5-FU bolus, which may have reduced hematological and non-hematological toxicity. The incidence and severity of oxaliplatin-induced neuropathy are associated with cumulative dosage. Grade 3-4 oxaliplatin-related neuropathy was observed in 10% to 15% of patients after exposure to a cumulative dose of 780 to 850 mg/m2[33]. In this study, grade 3 oxaliplatin-induced neuropathy occurred in only one patient without TA, who received a cumulative dose of oxaliplatin of 1,020 mg/m2. Bevacizumab has characteristic side effects such as hypertension, thrombotic events, hemorrhage and proteinuria. In the PRODIGE 20 trial, grade 3-4 thromboembolism and hypertension were 9.8% and 13.7%, respectively[30]. In another study, bevacizumab-related adverse events in elderly patients were similar to those of younger patients, with the exception of arterial thrombotic events, which appeared to increase in the older patients[27]. Similar to the previous study, arterial thrombosis (8.3%) and grade 1-2 hypertension (25%) were manageable in our study. Side effects related to cetuximab have also been reported in several studies, including grade 3-4 diarrhea and skin reactions occurring in more than 20% of elderly patients[33,34]. The incidence of anaphylaxis in elderly patients was rarely reported and not higher than in young patients[35]. In our study, cetuximab treatment in three patients resulted in acne-like skin side effects only in two of them. Therefore, the addition of TA was relatively tolerable and manageable even in elderly patients.

After the failure of the first-line chemotherapy, salvage chemotherapy in elderly patients is deter

Although this study showed clinical feasibility for combination chemotherapy with or without TA in extremely elderly patients with metastatic CRC, the study has some limitations. This study was a retrospective study with small sample size and had confounding factors such as two types of TA, different chemotherapy regimens, and various clinical circumstances. It is necessary to interpret the results of this study taking this into account. In elderly patients, it is important to improve the survival period as well as evaluate the quality of life. We believe that the comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) tool is useful in providing the best therapeutic option and optimal care for elderly patients most suitable for systemic chemotherapy. However, this study, which is a retrospective study, has a limitation in that it does not include quality of life and patients' feelings. Therefore, a further study using a CGA is needed to elucidate not only the treatment effect of systemic chemotherapy but also the quality of life in extremely elderly patients.

The significance of this study is as follows, despite these limitations. The study included only patients who were older than 80 years. On the other hand, most previous studies included patients who were between 65-80 years or reported subgroup analysis of older patients within clinical trials, which restricted the eligibility to patients aged 75 years or younger. Also, this study had a control group, compared with the group treated with TA. Therefore, this study may help to understand the role of targeted therapy and the potential of combination chemotherapy in extremely elderly patients with metastatic CRC.

Combination chemotherapy with TA for metastatic CRC may be considered even in elderly patients over 80 years of age with considerable caution for chemotherapy-related toxicity and risk of comorbidities. Also, salvage chemotherapy can help improve OS in extremely elderly patients. In these elderly patients with metastatic CRC, further studies are needed to improve the quality of life as well as an appropriate treatment regimen to improve the survival rate.

The efficacy and safety of combination chemotherapy for metastatic colorectal cancer (CRC) in extremely elderly patients has yet to be established.

Combination chemotherapy with targeted agent (TA) for metastatic CRC may be considered feasible in patients aged above 80 years.

To assess the clinical outcomes and feasibility of combination chemotherapy using a TA in extremely elderly patients with CRC.

Total 30 patients over 80 years of age with metastatic CRC were retrospectively reviewed.

The median progression-free survival and overall survival in patients treated with TA were 7.4 mo and 15.4 mo, respectively, compared with 4.4 mo and 15.6 mo in patients treated without TA.

Combination chemotherapy with TA for metastatic CRC may be considered even in elderly patients over 80 years of age with considerable caution for chemotherapy-related toxicity and risk of comorbidities.

This study may help to understand the role of targeted therapy and the potential of combination chemotherapy in extremely elderly patients with metastatic CRC.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Diez-Alonso M, Spain; Ren JY, China S-Editor: Wang LL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wang LL

| 1. | Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69:7-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13300] [Cited by in RCA: 15474] [Article Influence: 2579.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 2. | Siegel RL, Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, Fedewa SA, Butterly LF, Anderson JC, Cercek A, Smith RA, Jemal A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70:145-164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2268] [Cited by in RCA: 3270] [Article Influence: 654.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 3. | Jung KW, Won YJ, Kong HJ, Oh CM, Lee DH, Lee JS. Prediction of cancer incidence and mortality in Korea, 2014. Cancer Res Treat. 2014;46:124-130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Hurria A, Togawa K, Mohile SG, Owusu C, Klepin HD, Gross CP, Lichtman SM, Gajra A, Bhatia S, Katheria V, Klapper S, Hansen K, Ramani R, Lachs M, Wong FL, Tew WP. Predicting chemotherapy toxicity in older adults with cancer: a prospective multicenter study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3457-3465. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1199] [Cited by in RCA: 1335] [Article Influence: 95.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 5. | Lewis JH, Kilgore ML, Goldman DP, Trimble EL, Kaplan R, Montello MJ, Housman MG, Escarce JJ. Participation of patients 65 years of age or older in cancer clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1383-1389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 803] [Cited by in RCA: 813] [Article Influence: 37.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Murthy VH, Krumholz HM, Gross CP. Participation in cancer clinical trials: race-, sex-, and age-based disparities. JAMA. 2004;291:2720-2726. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1452] [Cited by in RCA: 1694] [Article Influence: 80.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | . Modulation of fluorouracil by leucovorin in patients with advanced colorectal cancer: evidence in terms of response rate. Advanced Colorectal Cancer Meta-Analysis Project. J Clin Oncol. 1992;10:896-903. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 863] [Cited by in RCA: 810] [Article Influence: 24.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | de Gramont A, Figer A, Seymour M, Homerin M, Hmissi A, Cassidy J, Boni C, Cortes-Funes H, Cervantes A, Freyer G, Papamichael D, Le Bail N, Louvet C, Hendler D, de Braud F, Wilson C, Morvan F, Bonetti A. Leucovorin and fluorouracil with or without oxaliplatin as first-line treatment in advanced colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2938-2947. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2950] [Cited by in RCA: 2825] [Article Influence: 113.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Douillard JY, Cunningham D, Roth AD, Navarro M, James RD, Karasek P, Jandik P, Iveson T, Carmichael J, Alakl M, Gruia G, Awad L, Rougier P. Irinotecan combined with fluorouracil compared with fluorouracil alone as first-line treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer: a multicentre randomised trial. Lancet. 2000;355:1041-1047. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2407] [Cited by in RCA: 2381] [Article Influence: 95.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Grothey A, Sargent D, Goldberg RM, Schmoll HJ. Survival of patients with advanced colorectal cancer improves with the availability of fluorouracil-leucovorin, irinotecan, and oxaliplatin in the course of treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1209-1214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 800] [Cited by in RCA: 794] [Article Influence: 37.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Tournigand C, André T, Achille E, Lledo G, Flesh M, Mery-Mignard D, Quinaux E, Couteau C, Buyse M, Ganem G, Landi B, Colin P, Louvet C, de Gramont A. FOLFIRI followed by FOLFOX6 or the reverse sequence in advanced colorectal cancer: a randomized GERCOR study. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:229-237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2282] [Cited by in RCA: 2200] [Article Influence: 104.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Presta LG, Chen H, O'Connor SJ, Chisholm V, Meng YG, Krummen L, Winkler M, Ferrara N. Humanization of an anti-vascular endothelial growth factor monoclonal antibody for the therapy of solid tumors and other disorders. Cancer Res. 1997;57:4593-4599. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Hurwitz H, Fehrenbacher L, Novotny W, Cartwright T, Hainsworth J, Heim W, Berlin J, Baron A, Griffing S, Holmgren E, Ferrara N, Fyfe G, Rogers B, Ross R, Kabbinavar F. Bevacizumab plus irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2335-2342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7832] [Cited by in RCA: 7733] [Article Influence: 368.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 14. | Cassidy J, Clarke S, Díaz-Rubio E, Scheithauer W, Figer A, Wong R, Koski S, Rittweger K, Gilberg F, Saltz L. XELOX vs FOLFOX-4 as first-line therapy for metastatic colorectal cancer: NO16966 updated results. Br J Cancer. 2011;105:58-64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 174] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Giantonio BJ, Catalano PJ, Meropol NJ, O'Dwyer PJ, Mitchell EP, Alberts SR, Schwartz MA, Benson AB 3rd; Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Study E3200. Bevacizumab in combination with oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin (FOLFOX4) for previously treated metastatic colorectal cancer: results from the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Study E3200. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1539-1544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1806] [Cited by in RCA: 1726] [Article Influence: 95.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Grothey A, Sugrue MM, Purdie DM, Dong W, Sargent D, Hedrick E, Kozloff M. Bevacizumab beyond first progression is associated with prolonged overall survival in metastatic colorectal cancer: results from a large observational cohort study (BRiTE). J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5326-5334. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 522] [Cited by in RCA: 509] [Article Influence: 29.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 17. | Van Cutsem E, Köhne CH, Hitre E, Zaluski J, Chang Chien CR, Makhson A, D'Haens G, Pintér T, Lim R, Bodoky G, Roh JK, Folprecht G, Ruff P, Stroh C, Tejpar S, Schlichting M, Nippgen J, Rougier P. Cetuximab and chemotherapy as initial treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1408-1417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2901] [Cited by in RCA: 3126] [Article Influence: 195.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 18. | Maughan TS, Adams RA, Smith CG, Meade AM, Seymour MT, Wilson RH, Idziaszczyk S, Harris R, Fisher D, Kenny SL, Kay E, Mitchell JK, Madi A, Jasani B, James MD, Bridgewater J, Kennedy MJ, Claes B, Lambrechts D, Kaplan R, Cheadle JP; MRC COIN Trial Investigators. Addition of cetuximab to oxaliplatin-based first-line combination chemotherapy for treatment of advanced colorectal cancer: results of the randomised phase 3 MRC COIN trial. Lancet. 2011;377:2103-2114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 766] [Cited by in RCA: 763] [Article Influence: 54.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 19. | Kirstein MM, Lange A, Prenzler A, Manns MP, Kubicka S, Vogel A. Targeted therapies in metastatic colorectal cancer: a systematic review and assessment of currently available data. Oncologist. 2014;19:1156-1168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 20. | Chiara S, Nobile MT, Vincenti M, Lionetto R, Gozza A, Barzacchi MC, Sanguineti O, Repetto L, Rosso R. Advanced colorectal cancer in the elderly: results of consecutive trials with 5-fluorouracil-based chemotherapy. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1998;42:336-340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 21. | Magné N, François E, Broisin L, Guardiola E, Ramaïoli A, Ferrero JM, Namer M. Palliative 5-fluorouracil-based chemotherapy for advanced colorectal cancer in the elderly: results of a 10-year experience. Am J Clin Oncol. 2002;25:126-130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 22. | Folprecht G, Cunningham D, Ross P, Glimelius B, Di Costanzo F, Wils J, Scheithauer W, Rougier P, Aranda E, Hecker H, Köhne CH. Efficacy of 5-fluorouracil-based chemotherapy in elderly patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: a pooled analysis of clinical trials. Ann Oncol. 2004;15:1330-1338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 209] [Cited by in RCA: 187] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 23. | Goldberg RM, Tabah-Fisch I, Bleiberg H, de Gramont A, Tournigand C, Andre T, Rothenberg ML, Green E, Sargent DJ. Pooled analysis of safety and efficacy of oxaliplatin plus fluorouracil/leucovorin administered bimonthly in elderly patients with colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4085-4091. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 377] [Cited by in RCA: 344] [Article Influence: 18.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Figer A, Perez-Staub N, Carola E, Tournigand C, Lledo G, Flesch M, Barcelo R, Cervantes A, André T, Colin P, Louvet C, de Gramont A. FOLFOX in patients aged between 76 and 80 years with metastatic colorectal cancer: an exploratory cohort of the OPTIMOX1 study. Cancer. 2007;110:2666-2671. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Seymour MT, Thompson LC, Wasan HS, Middleton G, Brewster AE, Shepherd SF, O'Mahony MS, Maughan TS, Parmar M, Langley RE; FOCUS2 Investigators; National Cancer Research Institute Colorectal Cancer Clinical Studies Group. Chemotherapy options in elderly and frail patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (MRC FOCUS2): an open-label, randomised factorial trial. Lancet. 2011;377:1749-1759. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 291] [Cited by in RCA: 320] [Article Influence: 22.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Van Cutsem E, Rivera F, Berry S, Kretzschmar A, Michael M, DiBartolomeo M, Mazier MA, Canon JL, Georgoulias V, Peeters M, Bridgewater J, Cunningham D; First BEAT investigators. Safety and efficacy of first-line bevacizumab with FOLFOX, XELOX, FOLFIRI and fluoropyrimidines in metastatic colorectal cancer: the BEAT study. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:1842-1847. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 391] [Cited by in RCA: 411] [Article Influence: 25.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Kozloff MF, Berlin J, Flynn PJ, Kabbinavar F, Ashby M, Dong W, Sing AP, Grothey A. Clinical outcomes in elderly patients with metastatic colorectal cancer receiving bevacizumab and chemotherapy: results from the BRiTE observational cohort study. Oncology. 2010;78:329-339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Cunningham D, Lang I, Marcuello E, Lorusso V, Ocvirk J, Shin DB, Jonker D, Osborne S, Andre N, Waterkamp D, Saunders MP; AVEX study investigators. Bevacizumab plus capecitabine versus capecitabine alone in elderly patients with previously untreated metastatic colorectal cancer (AVEX): an open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:1077-1085. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 422] [Cited by in RCA: 475] [Article Influence: 39.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Price TJ, Zannino D, Wilson K, Simes RJ, Cassidy J, Van Hazel GA, Robinson BA, Broad A, Ganju V, Ackland SP, Tebbutt NC. Bevacizumab is equally effective and no more toxic in elderly patients with advanced colorectal cancer: a subgroup analysis from the AGITG MAX trial: an international randomised controlled trial of Capecitabine, Bevacizumab and Mitomycin C. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:1531-1536. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Aparicio T, Bouché O, Taieb J, Maillard E, Kirscher S, Etienne PL, Faroux R, Khemissa Akouz F, El Hajbi F, Locher C, Rinaldi Y, Lecomte T, Lavau-Denes S, Baconnier M, Oden-Gangloff A, Genet D, Paillaud E, Retornaz F, François E, Bedenne L; for PRODIGE 20 Investigators. Bevacizumab+chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone in elderly patients with untreated metastatic colorectal cancer: a randomized phase II trial-PRODIGE 20 study results. Ann Oncol. 2018;29:133-138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Folprecht G, Kohne C-H, Bokemeyer C, Rougier P, Schlichting M, Heeger S. Colorectal cancer: Cetuximab and 1st-line chemotherapy in elderly and younger patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (MCRC): a pooled analysis of the CRYSTAL and OPUS studies. Ann Oncol. 2010;2:viii189-viii224. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Meta-analysis Group In Cancer; Piedbois P, Rougier P, Buyse M, Pignon J, Ryan L, Hansen R, Zee B, Weinerman B, Pater J, Leichman C, Macdonald J, Benedetti J, Lokich J, Fryer J, Brufman G, Isacson R, Laplanche A, Levy E. Efficacy of intravenous continuous infusion of fluorouracil compared with bolus administration in advanced colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:301-308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 716] [Cited by in RCA: 702] [Article Influence: 26.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Grothey A. Oxaliplatin-safety profile: neurotoxicity. Semin Oncol. 2003;30:5-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 201] [Cited by in RCA: 216] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Mohile SG, Dale W, Somerfield MR, Schonberg MA, Boyd CM, Burhenn PS, Canin B, Cohen HJ, Holmes HM, Hopkins JO, Janelsins MC, Khorana AA, Klepin HD, Lichtman SM, Mustian KM, Tew WP, Hurria A. Practical Assessment and Management of Vulnerabilities in Older Patients Receiving Chemotherapy: ASCO Guideline for Geriatric Oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:2326-2347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 975] [Cited by in RCA: 997] [Article Influence: 142.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Sastre J, Grávalos C, Rivera F, Massuti B, Valladares-Ayerbes M, Marcuello E, Manzano JL, Benavides M, Hidalgo M, Díaz-Rubio E, Aranda E. First-line cetuximab plus capecitabine in elderly patients with advanced colorectal cancer: clinical outcome and subgroup analysis according to KRAS status from a Spanish TTD Group Study. Oncologist. 2012;17:339-345. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |