Published online Sep 16, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i26.9434

Peer-review started: April 19, 2022

First decision: June 7, 2022

Revised: June 19, 2022

Accepted: August 6, 2022

Article in press: August 6, 2022

Published online: September 16, 2022

Processing time: 135 Days and 22 Hours

Segmental zoster paresis, depending on the affected area, can present with severe clinical manifestations and render patients unable to perform activities of daily living. Therefore, it is necessary to diagnose and treat such a condition rapidly. No studies have reported using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to identify clinical abnormalities associated with this condition or its complete recovery. This rare case report evaluated the changes in MRI findings before and after the patient's motor symptoms recovered.

A 79-year-old woman with a history of rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis visited the hospital for skin rashes and pain in the C5-T2 segments. The diagnosis was herpes zoster infection, and treatment was initiated. However, motor weakness suddenly occurred 14 d after the initial symptom presentation. We confirmed abnormal findings in the nerves and muscles invaded by the shingles using electromyography and MRI. After 17 mo, the patient's symptoms had completely normalized, and MRI confirmed that there were no abnormalities.

MRI can be a useful diagnostic modality for segmental zoster paresis and patient evaluation during recovery from motor complications.

Core Tip: Segmental zoster paresis is a rare motor complication of herpes zoster infection. Generalized severe pain and a low incidence of motor complications make its diagnosis challenging for clinicians. It can present with various motor symptoms depending on the affected area. Although the prognosis of segmental zoster paresis is known to be fair, it is important to administer multiple treatments promptly, considering the relatively long period required for recovery from motor symptoms. Magnetic resonance imaging can be advantageous in the diagnosis of segmental zoster paresis and its evaluation after recovery.

- Citation: Park J, Lee W, Lim Y. Complete recovery from segmental zoster paresis confirmed by magnetic resonance imaging: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(26): 9434-9439

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i26/9434.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i26.9434

Herpes zoster (HZ) is a sporadic disease caused by the reactivation of latent varicella zoster virus (VZV) in the dorsal root ganglion or cranial nerve sensory ganglion. The prevalence of HZ infection is approximately 10%–20% in the general population[1]. HZ infection is characterized by unilateral vesicular skin rashes and is often associated with severe pain. The most common complication of HZ infection is postherpetic neuralgia, which persists for months to years after the skin rash heals.

Motor complications rarely occur along the involved sensory segments and result in muscle weakness, referred to as segmental zoster paresis. Motor complications are due to the spread of VZV from the dorsal root ganglion to ventral horn cells. The incidence of motor complications is 0.5%–5% in patients infected with HZ[2,3].

Here, we report a case of severe pain with motor paresis in the left upper extremity of a 79-year-old woman due to an HZ infection. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed to evaluate motor paresis. This is a rare case report in which we evaluated the changes in MRI findings before and after the patient's motor symptoms recovered.

A 79-year-old woman (height, 155.0 cm; weight, 50 kg) visited our hospital's pain clinic with a characteristic rash of HZ following the distribution of C5-T2 left dermatomes with severe pain scoring 10 on the numeric rating scale. Fourteen days after the onset of her initial symptoms, she complained of motor weakness without sensory defects in her left upper extremity.

Considering the patient’s severe pain, we decided to hospitalize her. Upon her first visit to our pain medicine clinic, she was alert, and her vital signs were stable except for her body temperature (37.2 °C). The patient was clinically diagnosed with an HZ infection. Medical treatment was initiated with intravenous acyclovir (5 mg/kg) for 9 d and analgesics (celecoxib, targin CR). In addition, neuraxial block for pain control, including cervical plexus block, axillary nerve block, and cervical epidural block with a long-acting local anesthetic (0.15% ropivacaine) injection, was performed during her hospitalization. Because of her current medication history (ustekinumab and methotrexate), we did not use glucocorticoids for injection. Symptoms of skin rash and pain were relieved over time.

However, 14 d after the initial symptoms, the patient complained of motor weakness without sensory defects in her left upper extremity. There was no history of recent trauma or surgery.

The patient had underlying diseases, including hypertension, psoriasis, and rheumatoid arthritis. Her prescription included amlodipine, ustekinumab, and methotrexate.

Personal and family histories were unremarkable.

The patient was examined neurologically to assess the motor dysfunction of the left upper extremity. She complained that she could not lift her upper extremity against gravity. (Shoulder abduction/ adduction G2+/G2+, elbow flexion/extension G3+/G3+).

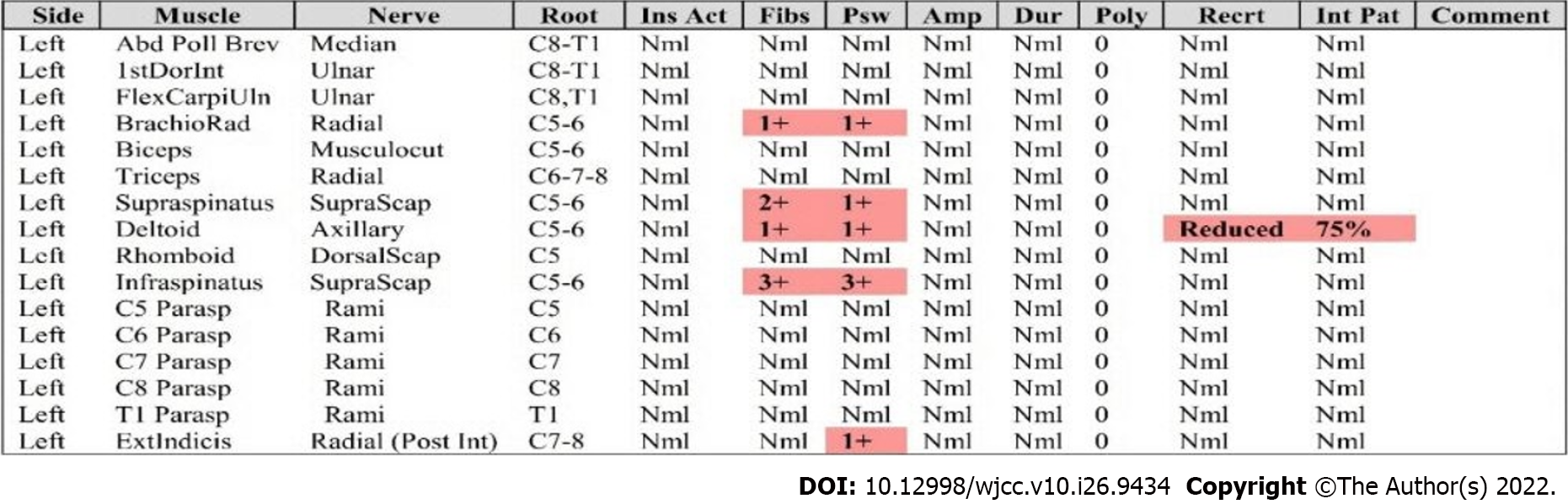

Initial laboratory test results were within normal limits; complete blood cell count and blood chemistry tests, such as renal panel, hepatic panel, and coagulation tests, were performed. Electromyography (EMG) of the left arm suggested denervation potentials in the brachioradialis, supraspinatus, infraspinatus, deltoid, extensor indicis, and C6 paraspinalis muscles (Figure 1).

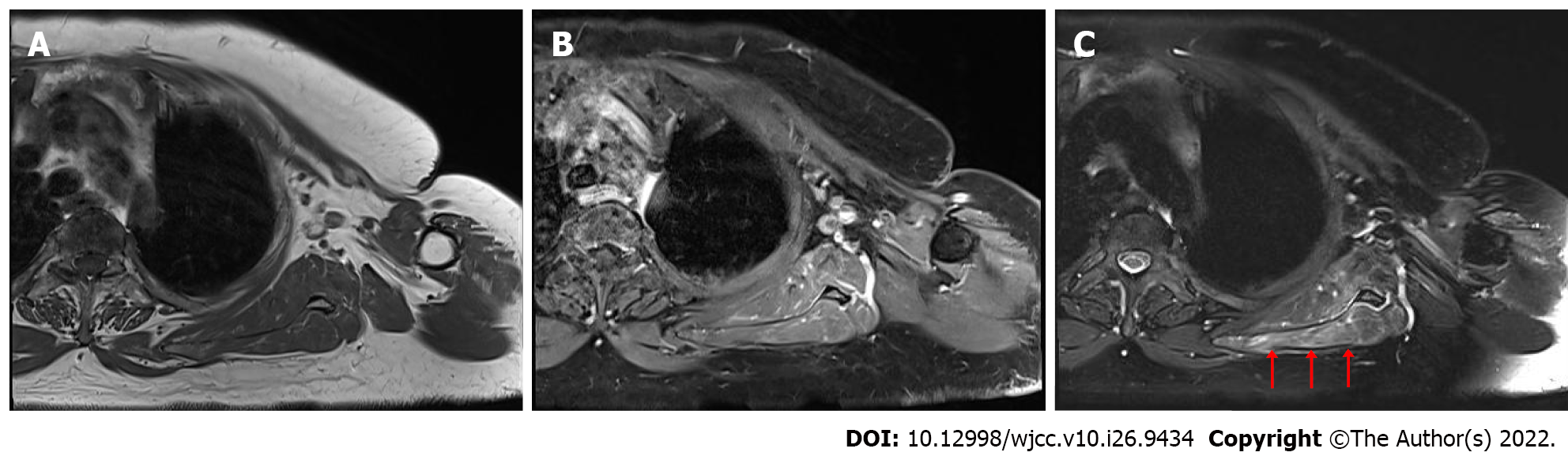

MRI of the brachial plexus showed a hyperintense signal on T2-weighted images and an isointense signal on T1-weighted images without definite enhancement in the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and subscapularis muscles of the left shoulder, indicating the potential for neuropathy without any muscle injury (Figure 2).

The patient was diagnosed with segmental zoster paresis as a complication of HZ infection.

After consultation with a neurologist, we initiated treatment with prednisolone 40 mg for 5 d, which was then reduced by 10 mg every 5 d. In addition, she repeatedly underwent nerve block procedures (cervical plexus, axillary nerve, and cervical epidural blocks) with local anesthetic (0.15% ropivacaine diluted with normal saline) injections.

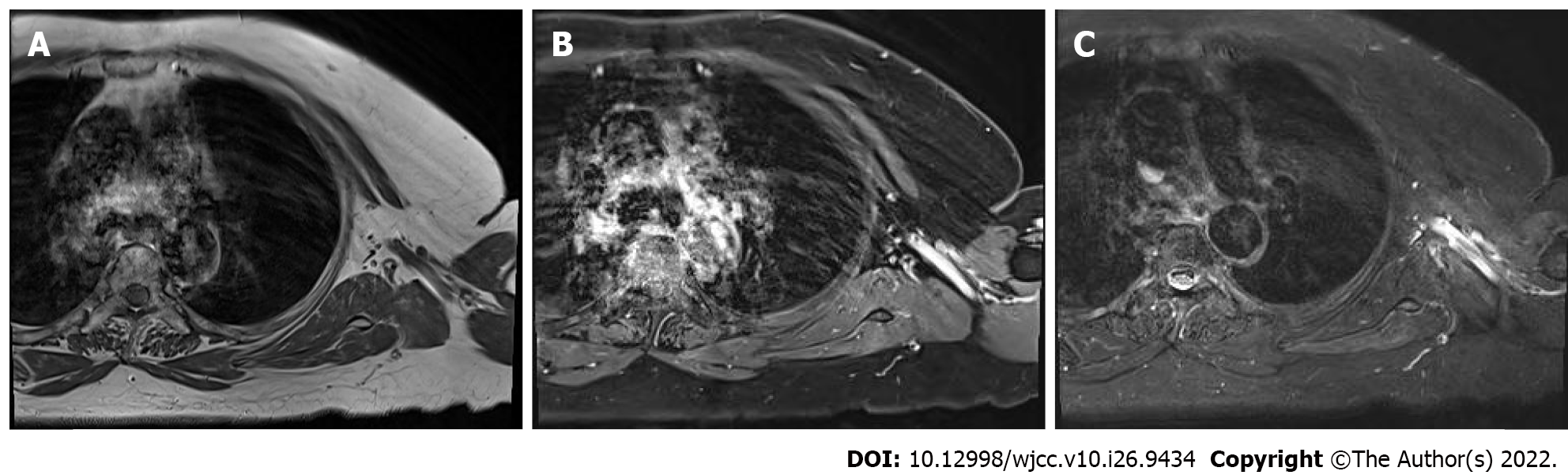

A month later, the patient showed some improvement in her motor symptoms (motor grade 3) and was discharged from the hospital. During the outpatient follow-up after 10 mo, she could move her left upper extremity against gravity with some resistance (motor grade 4). Six months later, she fully recovered to motor grade 5. MRI of the brachial plexus was performed again to study the changes compared to the previous imaging findings. All previous abnormal findings disappeared, and there was no difference compared with the right upper extremity (Figure 3). Follow-up EMG was not performed because the patient refused it due to the discomfort of the examination and the high cost.

HZ infection is associated with host immune status. The risk factors include age and immunocompromised status. The major risk factor is old age; after the age of 50 years, the incidence of HZ infection increases dramatically[4]. Because immunocompromised patients have poor T cell-mediated immunity, the risk of VZV reactivation increases in transplant recipients, patients with autoimmune diseases, and those undergoing immunosuppressive therapies. This patient was in the high-risk group based on her age (79 years), rheumatoid arthritis history, and medication history of ustekinumab and methotrexate. The common characteristic manifestation of HZ infection is dermatomal skin lesions with pain. However, as seen in this case, motor paresis can occur in 0.5%–5% of patients infected with HZ, and is called segmental zoster paresis. Segmental zoster paresis has been reported to occur in the same dermatome 2–3 wk after the skin manifestations occur[5]. Depending on the site of infection of the dermatome, various symptoms can occur. Motor complications can appear as cranial (Ramsay-Hunt syndrome, involving the facial nerve) and peripheral (motor paresis of extremities, diaphragm, or abdominal muscles) neuropathies. Moreover, visceral involvement of the urinary (bladder dysfunction) and gastrointestinal tracts (colon pseudo-obstruction) can occur[6]. For example, limb segmental zoster paresis can occur if the C5-7 or L2-4 nerve roots are affected. Abdominal wall muscles, receiving nerve supply from the T6-L1, can present as a pseudohernia[7]. Therefore, physicians may misjudge whether surgical treatment is necessary. Bladder and bowel dysfunction complications can occur when HZ infection involves the sacral sensory ganglia.

MRI could play a diagnostic role, demonstrating hyperintense signal on T2-weighted images in muscular lesions[8]. In water-sensitive MRI sequences, denervated muscles show higher signal intensity than normal muscles, secondary to increased extracellular water[9]. This abnormal finding of MRI is nonspecific and can appear in other conditions, for example, infections, inflammation, ischemia, infarction, metabolic disorders, contusion, tumors, and rhabdomyolysis[10]. However, when we consider the MRI findings of signal abnormalities on T2-weighted images without abnormal signals on T1WI of denervated muscles and patients’ clinical features, MRI can help clinicians establish differential diagnoses from other conditions because denervation injury only affects the muscles supplied by those nerves. Signal abnormalities on T2WI can last approximately 3 mo[11]. Although the pathophysiology of segmental zoster paresis is unclear, MRI findings, in this case, suggest that the most probable cause might be the direct spread of the VZV from the sensory ganglion to the ventral horn cells or ventral spinal nerve roots, which some studies have previously reported[12]. Another study demonstrated that motor neuropathy caused by VZV is an inflammatory demyelinating process[13].

Treatment of segmental zoster paresis, as in general HZ infection, is helpful when administered as a combination of antiviral drugs, glucocorticoids, neuraxial block, and physical therapy. Early administration of antiviral drugs is important to decrease the incidence of motor complications and degree of pain[14,15]. The early administration of glucocorticoids could decrease demyelination of the involved nerve segments and prevent degeneration of axons[16]. Kinishi et al[17] reported that therapy with acyclovir with a high dose of steroids was proven to maintain nerve function in good condition, as evidenced by the nerve excitability test. Moreover, in the Ramsay-Hunt syndrome, the therapy resulted in an improved recovery rate of the facial nerve. Other researches have reported that, within 2 wk after initial symptoms, nerve block procedures can decrease the severity of pain and the incidence of complications[18].

Regarding prognosis, the ultimate recovery of motor strength is good in 70%–80% of the cases, although this may take a few months to a few years[19]. Although the patient, in this case, belonged to the high-risk group, it is important to note that she fully recovered after approximately 17 mo of early treatment with antiviral agents, glucocorticoids, and neuraxial blocks.

Segmental zoster paresis, depending on the affected area, can present with severe clinical manifestations and render patients unable to carry out the activities of daily living. However, a good prognosis can be expected through prompt administration of optimal treatments, such as in this case. MRI may play a useful diagnostic role in segmental zoster paresis and patient evaluation after recovery from motor complications.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report's scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Gao L, China; Guo XW, China; Liang P, China; Wang XJ, China S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Fan JR

| 1. | Insinga RP, Itzler RF, Pellissier JM, Saddier P, Nikas AA. The incidence of herpes zoster in a United States administrative database. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:748-753. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 359] [Cited by in RCA: 358] [Article Influence: 17.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Gupta SK, Helal BH, Kiely P. The prognosis in zoster paralysis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1969;51:593-603. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Thomas JE, Howard FM Jr. Segmental zoster paresis--a disease profile. Neurology. 1972;22:459-466. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 187] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kawai K, Gebremeskel BG, Acosta CJ. Systematic review of incidence and complications of herpes zoster: towards a global perspective. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e004833. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 667] [Cited by in RCA: 597] [Article Influence: 54.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kennedy PG, Barrass JD, Graham DI, Clements GB. Studies on the pathogenesis of neurological diseases associated with Varicella-Zoster virus. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 1990;16:305-316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Dobrev H, Atanassova P, Sirakov V. Postherpetic abdominal-wall pseudohernia. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33:677-678. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Healy C, McGreal G, Lenehan B, McDermott EW, Murphy JJ. Self-limiting abdominal wall herniation and constipation following herpes zoster infection. QJM. 1998;91:788-789. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Samuraki M, Yoshita M, Yamada M. MRI of segmental zoster paresis. Neurology. 2005;64:1138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Polak JF, Jolesz FA, Adams DF. Magnetic resonance imaging of skeletal muscle. Prolongation of T1 and T2 subsequent to denervation. Invest Radiol. 1988;23:365-369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Schulze M, Kötter I, Ernemann U, Fenchel M, Tzaribatchev N, Claussen CD, Horger M. MRI findings in inflammatory muscle diseases and their noninflammatory mimics. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192:1708-1716. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kato K, Tomura N, Takahashi S, Watarai J. Motor denervation of tumors of the head and neck: changes in MR appearance. Magn Reson Med Sci. 2002;1:157-164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hanakawa T, Hashimoto S, Kawamura J, Nakamura M, Suenaga T, Matsuo M. Magnetic resonance imaging in a patient with segmental zoster paresis. Neurology. 1997;49:631-632. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Fabian VA, Wood B, Crowley P, Kakulas BA. Herpes zoster brachial plexus neuritis. Clin Neuropathol. 1997;16:61-64. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Bilal S, Iqbal M, O'Moore B, Alam J, Suliman A. Monoparesis secondary to herpes zoster. Ir J Med Sci. 2011;180:603-604. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Wendling D, Langlois S, Lohse A, Toussirot E, Michel F. Herpes zoster sciatica with paresis preceding the skin lesions. Three case-reports. Joint Bone Spine. 2004;71:588-591. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Meng Y, Zhuang L, Jiang W, Zheng B, Yu B. Segmental Zoster Paresis: A Literature Review. Pain Physician. 2021;24:253-261. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Kinishi M, Amatsu M, Mohri M, Saito M, Hasegawa T, Hasegawa S. Acyclovir improves recovery rate of facial nerve palsy in Ramsay Hunt syndrome. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2001;28:223-226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Conliffe TD, Dholakia M, Broyer Z. Herpes zoster radiculopathy treated with fluoroscopically-guided selective nerve root injection. Pain Physician. 2009;12:851-853. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Chang CM, Woo E, Yu YL, Huang CY, Chin D. Herpes zoster and its neurological complications. Postgrad Med J. 1987;63:85-89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |