Published online Sep 16, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i26.9384

Peer-review started: April 11, 2022

First decision: June 8, 2022

Revised: July 7, 2022

Accepted: August 1, 2022

Article in press: August 1, 2022

Published online: September 16, 2022

Processing time: 144 Days and 4.2 Hours

Single-organ vasculitis (SOV) is characterized by inflammation of a blood vessel, affecting one organ, such as the skin, genitourinary system, or the aorta without systemic features. Gastrointestinal SOV is rare, with hepatic artery involvement reported only in two prior published cases. Herein, we presented a case of isolated hepatic artery vasculitis presenting after Pfizer-BioNTech mRNA corona virus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccination.

A 50-year-old woman with hypertension presented to our Emergency Department with recurrent diffuse abdominal pain that localized to the epigastrium and emesis without diarrhea that began eight days after the second dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine. Blood work revealed an elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) of 19 mg/L (normal < 4.8 mg/L), alkaline phosphatase 150 U/L (normal 25-105 U/L), gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) 45 U/L (normal < 43 U/L) and elevated immunoglobulins (Ig) G 18.4 g/L (normal 7-16 g/L) and IgA 4.4 g/L (normal 0.7-4 g/L). An abdominal computed tomography revealed findings in keeping with hepatic artery vasculitis. A detailed review of her history and examination did not reveal infectious or systemic autoimmune causes of her presentation. An extensive autoimmune panel was unremarkable. COVID-19 polymerase chain reaction nasopharyngeal swab, human immunodeficiency virus, viral hepatitis and Heliobacter pylori serology were negative. At six months, the patient’s symptoms, and blood work spontaneously normalized.

High clinical suspicion of SOV is required for diagnosis in patients with acute abdominal pain and dyspepsia.

Core Tip: Single organ vasculitis (SOV) of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract is uncommon with hepatic artery involvement rarely reported. It presents with abdominal pain and often without changes in inflammatory or other biomarkers. It is diagnosed radiographically or incidentally via surgical specimens. mRNA coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccines have been stipulated to contribute to inflammatory side- effects such as myocarditis, and autoimmune hepatitis. The diagnosis of GI SOV should be considered as a potential cause of acute abdominal pain following COVID-19 mRNA vaccination.

- Citation: Kaviani R, Farrell J, Dehghan N, Moosavi S. Single organ hepatic artery vasculitis as an unusual cause of epigastric pain: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(26): 9384-9389

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i26/9384.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i26.9384

Single organ vasculitis (SOV) of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract is a rare manifestation of blood vessel inflammation. It can affect small, medium, and large-sized vessels and a variety of organs[1,2]. SOV can be further subdivided by the extent it affects an organ and thereby described as focal, multifocal, or diffuse[2]. One study comparing localized necrotizing arteritis to classic polyarteritis nodosa found that the former demonstrated localized fibrinoid necrosis in the intima and inner media of a vessel wall, whereas the latter affected the outer media and adventitia[2]. Histologically, SOV appears as granulomatous or non-granulomatous. Granulomatous vasculitis involves pleomorphic inflammation typically made of lymphocyte and macrophage aggregates with or without giant cells[1]. In non-granulomatous vasculitis, inflammatory infiltrates are predominantly made up of lymphocytes or neutrophils and may exhibit features of vessel wall necrosis[1]. Though, SOV histological findings can be indistinguishable from systemic vasculitis.

GI SOV most commonly affects the gallbladder, small intestine, and appendix. It presents similarly to systemic vasculitis with GI manifestations of abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and bleeding. In contrast, SOV often presents with normal inflammatory and autoimmune markers[1,3-6]. GI SOV is diagnosed radiographically or incidentally on surgical specimens. Up to 26% of SOV cases may progress to a systemic process, thereby at least six months of follow-up is required to exclude systemic involvement[1,2,7]. Single organ hepatic artery vasculitis is rare, reported only in case reports[7,8]. Herein, we discussed a case of isolated hepatic artery vasculitis presenting as dyspepsia, eight days following the second dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccine.

A 50-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with recurrent abdominal pain following the second dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine.

The patient developed two days of diffuse abdominal pain, chills, and emesis without diarrhea or fever, eight days following her COVID-19 vaccination. The patient had tolerated the first COVID-19 vaccine dose six weeks beforehand with no side-effects. The patient had no changes to her bowel movements, no sick contacts, and no toxic ingestions including alcohol, raw fish, or undercooked meats. There were no symptoms of an upper respiratory tract infection. The autoimmune review of systems was negative. The patient did not use herbal or over-the-counter supplements and is a lifelong non-smoker.

She presented to the emergency department following two days of symptoms and was diagnosed with dyspepsia and received a prescription of pantoprazole 40mg once daily by mouth. Her pain improved transiently, but she represented one week later with sudden onset of sharp, epigastric pain without nausea, diarrhea, fever, rigors, or rash.

The patient has a history of an ectopic kidney and hypertension treated with nifedipine. Her surgical history includes a remote appendectomy. In her childhood, she had an episode of jaundice with hepatitis that had not recurred. The patient had a one-year history of non-specific intermittent lower abdominal pain with a normal computed tomographic (CT) of the abdomen performed three weeks prior to presentation.

The patient denied any family history of inflammatory and autoimmune disorders.

On examination, the patient was afebrile with a blood pressure of 174/90, heart rate of 87 beats per minute, and oxygen saturation in room air of 97% with 18 breaths per minute. She had right-sided abdominal tenderness without rigidity, guarding or rebound tenderness with a negative murphy’s sign. The cardiorespiratory exam was normal. There were no features of joint swelling or rash.

Blood work revealed an elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) at 19 mg/L (normal < 4.8 mg/L), Alkaline phosphatase 150 U/L (normal 30-105 U/L) and gamma-glutamyl transferase at 45 U/L (normal < 43 U/L). The rest of the liver enzymes and bilirubin were normal: ALT 17 U/L (normal 5-45 U/L), AST 40 U/L (normal 10-40 U/L), Lipase 41 U/L (normal < 55 U/L), and total Bilirubin 7 umol/L (normal < 20 umol/L). A complete blood count was normal with an international normalized ratio of 0.9 (normal 0.9-1.2). Metabolic investigations showed a normal lactate dehydrogenase, thyroid-stimulating hormone 1.61 mU/L (normal 0.32-5.04 mU/L), albumin 49 g/L (normal 35-48 g/L), normal renal function and electrolytes. Infectious work-up with urine analysis, screening serology for human immunodeficiency virus, Hepatitis B and C, and Heliobacter pylori were negative. COVID-19 polymerase chain reaction nasopharyngeal swab was negative.

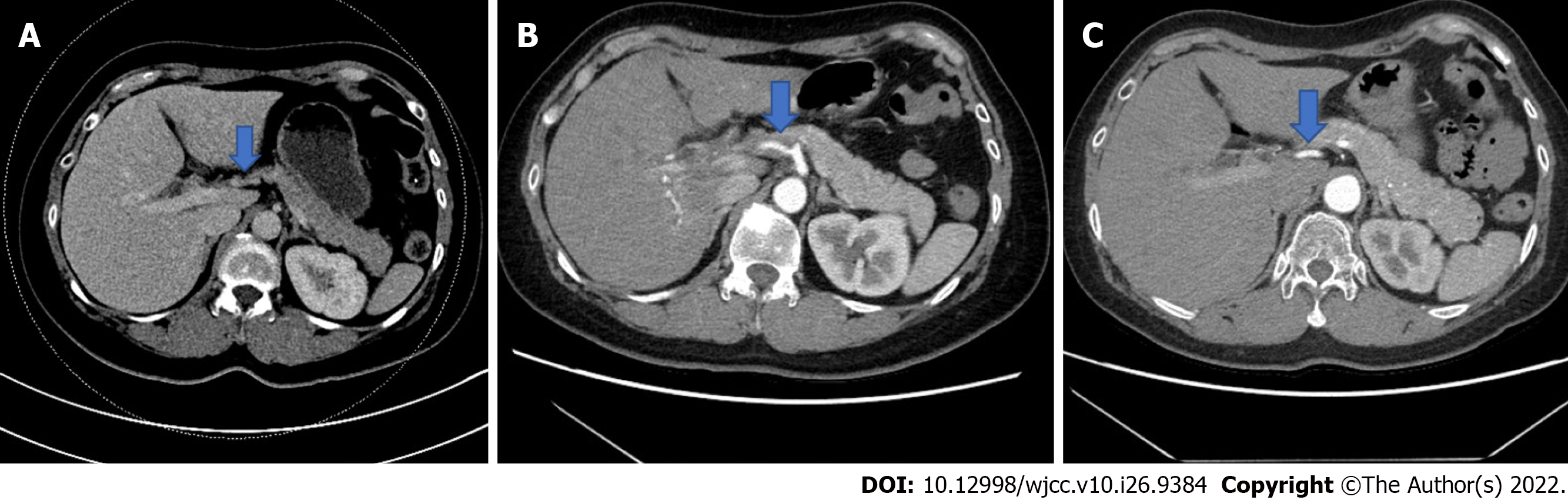

Initial imaging with an abdominal doppler ultrasound revealed a prominence of the vessels at the porta hepatis with possible hepatic artery wall thickening. A computed tomography (CT) image of the abdomen, obtained on the same day, revealed interval development of a thick rind of soft tissue thickening surrounding the hepatic artery with severely focal distal narrowing and beaded intrahepatic arterial branches. These findings were new from her normal CT scan three weeks prior and were radiographically consistent with hepatic artery vasculitis (Figure 1).

Autoimmune workup was remarkable for an elevated immunoglobulin (Ig) panel: IgG 18.4 g/L (normal 7-16 g/L) and IgA 4.4 g/L (normal 0.7-4 g/L) were elevated; IgM was normal at 0.72 g/L (normal 0.4-2.3 g/L). The rest of the autoimmune panel was normal: antinuclear antibody 0.2 IU/ml (normal < 0.7 IU/ml), antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies < 0.2 U (normal < 1.0 U), undetected cryoglobulins, complement C3 1.88 g/L (normal 0.90-1.90 g/L), complement C4 0.43 g/L (normal 0.13-0.46 g/L), rheumatoid factor < 10 kU/L (normal < 12 kU/L), and negative extractable nuclear antibody panel including Sm, RNP, SS-A, SS-B, Scl-70 and Jo-1.

The final diagnosis of the presented case is hepatic artery vasculitis.

The patient continued her pantoprazole prescription. The patient was followed clinically without immunosuppression given her stability, mild elevation in CRP, and intact liver function.

Her symptoms resolved spontaneously one week following her second emergency department presentation. At two-month follow-up, a repeat abdominal CT scan showed complete resolution of her vasculitis with normalization of CRP. The GGT normalized at 2 mo and Alkaline phosphatase normalized by 6 mo. Immunoglobulins remained elevated at 6-month follow-up: IgG 18.2 g/L (normal 7-16 g/L), IgA 4.61 g/L (normal 0.7-4 g/L). The patient remained clinically asymptomatic without systemic features of vasculitis.

We report a rare case of hepatic artery SOV presenting eight days after the second dose of a COVID-19 mRNA vaccine based on congruent radiographic assessment, elevated inflammatory markers and cholestatic liver enzymes.

In a ten-year study review of 130000 GI histological specimens collected from biopsies and surgical resections, only 29 (0.02%) patients with vasculitis were identified[6]. Of these 29 patients, eight had SOV in the gallbladder, small and large bowels. Notably, there were no hepatic manifestation[6]. Mali et al[7] reported a case of hepatic artery vasculitis diagnosed on imaging and without systemic involvement at six-month follow-up. In this case, inflammatory and autoimmune markers remained normal, and the patient was treated successfully with pulse steroids and tapering prednisone[7].

Interestingly, our patient’s symptoms and inflammatory markers resolved without immunosuppression, but there remains uncertainty on the natural history of SOV. The pattern of inflammatory markers in SOV remains unclear and can sometimes be normal at presentation making it a challenging diagnosis. In one case-series of eighteen patients with histologically or radiographically confirmed SOV, ten patients were treated with prednisone and three received pulse steroids. Two of the cases were managed with surgical resection[5].

In our case, given the history of hypertension, segmental arterial mediolysis (SAM), a rare non-inflammatory, non-atherosclerotic vasculopathy, characterized by lysis of the medial arterial wall layer, was considered. SAM can present similarly, often without an elevation in inflammatory markers and affecting the hepatic artery[9-11]. However SAM does not typically present with stenosis and wall thickening radiographically. Infectious causes to the patient’s presentations were considered, however, in the absence of other pertinent findings, such as diarrhea, persistent emesis, and history of toxin exposure coupled with negative viral investigations made infectious etiologies less likely. The diagnosis of SOV is supported by the characteristic radiological findings in combination with CRP and liver enzyme elevation in the absence of infectious exposure. A systemic process like vasculitis or granulomatous disease was also unlikely in our case, given the patient's continued absence of systemic symptoms at the six-month follow-up.

This case raises questions as to whether the patient’s presentation was coincidental with concomitant dyspepsia that responded to pantoprazole, or if the COVID-19 vaccine was causative or rather temporally correlated with the hepatic artery vasculitis. COVID-19 infection has been linked to the development and reactivation of autoimmune diseases.11 It is postulated that COVID-19 mRNA vaccines can act similarly to the infection through molecular mimicry[12]. Autoimmune hepatitis and systemic vasculitis cases following COVID-19 vaccines have been reported, suggesting an associated inflammatory process[13-19]. Reports on post-vaccine myocarditis and pericarditis have shown that Inflammatory responses typically occur three to four days after vaccination but this can range from hours up to 3 mo post-vaccine[20,21]. These presentations can also occur after the second vaccine dose in the absence of reactions to the first dose. Further long-term vaccination safety data is required to draw any conclusions regarding the possible gastrointestinal inflammatory effects associated with COVID-19 mRNA vaccination.

Single organ vasculitis is rare with hepatic artery involvement reported only in case reports. We outlined a case of hepatic artery vasculitis, presenting eight days following the second dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine. Further studies are needed to conclude the temporal association, if any, of SOV with COVID-19 vaccines. Close follow-up of SOV is required to exclude progression to systemic vasculitis. Severe cases may require treatment with immunosuppression to reduce morbidity and mortality.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Canada

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Al-Ani RM, Iraq; Dilek ON, Turkey S-Editor: Wang LL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wang LL

| 1. | Hernández-Rodríguez J, Hoffman GS. Updating single-organ vasculitis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2012;24:38-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Atisha-Fregoso Y, Hinojosa-Azaola A, Alcocer-Varela J. Localized, single-organ vasculitis: clinical presentation and management. Clin Rheumatol. 2013;32:1-6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Pagnoux C, Mahr A, Cohen P, Guillevin L. Presentation and outcome of gastrointestinal involvement in systemic necrotizing vasculitides: analysis of 62 patients with polyarteritis nodosa, microscopic polyangiitis, Wegener granulomatosis, Churg-Strauss syndrome, or rheumatoid arthritis-associated vasculitis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2005;84:115-128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 280] [Cited by in RCA: 256] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Soowamber M, Weizman AV, Pagnoux C. Gastrointestinal aspects of vasculitides. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;14:185-194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Salvarani C, Calamia KT, Crowson CS, Miller DV, Broadwell AW, Hunder GG, Matteson EL, Warrington KJ. Localized vasculitis of the gastrointestinal tract: a case series. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2010;49:1326-1335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Zhang X, Furth EE, Tondon R. Vasculitis Involving the Gastrointestinal System Is Often Incidental but Critically Important. Am J Clin Pathol. 2020;154:536-552. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Mali P, Muduganti SR, Goldberg J. Rare Case of Vasculitis of the Hepatic Artery. Clin Med Res. 2015;13:169-172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Thietart S, Mekinian A, Delorme S, Lequoy M, Gobert D, Arrivé L, Fain O. [Vasculitis of the hepatic artery: A case of a single-organ vasculitis]. Rev Med Interne. 2017;38:847-849. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 9. | Skeik N, Olson SL, Hari G, Pavia ML. Segmental arterial mediolysis (SAM): Systematic review and analysis of 143 cases. Vasc Med. 2019;24:549-563. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Naidu SG, Menias CO, Oklu R, Hines RS, Alhalabi K, Makar G, Shamoun FE, Henkin S, McBane RD. Segmental Arterial Mediolysis: Abdominal Imaging of and Disease Course in 111 Patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2018;210:899-905. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Costello F, Dalakas MC. Cranial neuropathies and COVID-19: Neurotropism and autoimmunity. Neurology. 2020;95:195-196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 416] [Cited by in RCA: 363] [Article Influence: 72.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Velikova T, Georgiev T. SARS-CoV-2 vaccines and autoimmune diseases amidst the COVID-19 crisis. Rheumatol Int. 2021;41:509-518. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 27.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Bril F, Al Diffalha S, Dean M, Fettig DM. Autoimmune hepatitis developing after coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccine: Causality or casualty? J Hepatol. 2021;75:222-224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 41.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Vuille-Lessard É, Montani M, Bosch J, Semmo N. Autoimmune hepatitis triggered by SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. J Autoimmun. 2021;123:102710. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 21.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | McShane C, Kiat C, Rigby J, Crosbie Ó. The mRNA COVID-19 vaccine-A rare trigger of autoimmune hepatitis? J Hepatol. 2021;75:1252-1254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 17.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Rocco A, Sgamato C, Compare D, Nardone G. Autoimmune hepatitis following SARS-CoV-2 vaccine: May not be a casuality. J Hepatol. 2021;75:728-729. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 18.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Erler A, Fiedler J, Koch A, Heldmann F, Schütz A. Leukocytoclastic Vasculitis After Vaccination With a SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021;73:2188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Shakoor MT, Birkenbach MP, Lynch M. ANCA-Associated Vasculitis Following Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine. Am J Kidney Dis. 2021;78:611-613. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 33.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Obeid M, Fenwick C, Pantaleo G. Reactivation of IgA vasculitis after COVID-19 vaccination. Lancet Rheumatol. 2021;3:e617. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Fazlollahi A, Zahmatyar M, Noori M, Nejadghaderi SA, Sullman MJM, Shekarriz-Foumani R, Kolahi AA, Singh K, Safiri S. Cardiac complications following mRNA COVID-19 vaccines: A systematic review of case reports and case series. Rev Med Virol. 2021;e2318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Barda N, Dagan N, Ben-Shlomo Y, Kepten E, Waxman J, Ohana R, Hernán MA, Lipsitch M, Kohane I, Netzer D, Reis BY, Balicer RD. Safety of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 Vaccine in a Nationwide Setting. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:1078-1090. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 669] [Cited by in RCA: 721] [Article Influence: 180.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |