Published online Sep 6, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i25.9168

Peer-review started: April 29, 2022

First decision: May 30, 2022

Revised: June 6, 2022

Accepted: July 29, 2022

Article in press: July 29, 2022

Published online: September 6, 2022

Processing time: 119 Days and 7.9 Hours

As an autoimmune disease, systemic lupus erythaematosus (SLE) can affect multiple systems of the body and is mainly treated by steroids and immunosuppressive agents. SLE results in a long-term immunocompromised state with the potential of infection complications (e.g., bacterial, fungal and viral infections). Abdominal pain or acute abdomen are frequently the only manifestations of SLE at disease onset or during the early stage of the disease course. Thus, multidisciplinary collaboration is required to identify these patients because timely diagnosis and treatment are crucial for improving their prognosis.

Herein, we reported a case of an SLE patient with visceral varicella that was identified after the onset of abdominal pain. The 16-year-old female patient with SLE was admitted to our hospital due to initial attacks of abdominal pain and intermittent fever. The patient’s condition rapidly became aggravated within a short time after admission, with large areas of vesicular rash, severe pneumonia, respiratory failure, shock, and haematologic system and hepatic function impairment. Based on multidisciplinary collaboration, the patient was diagnosed with visceral disseminated varicella and was administered life support, antiviral (acyclovir), immunomodulatory (intravenous injection of human immunoglobulin), anti-infection (vancomycin) and anti-inflammatory (steroid) therapies. After treatment, her clinical symptoms and laboratory indicators gradually improved, and the patient was discharged.

SLE patients long treated with steroids and immunosuppressive agents are susceptible to various infections. Considering that visceral varicella with abdo

Core Tip: The long-term use of steroids and immunosuppressive agents for the treatment of systemic lupus erythaematosus may decrease immunity, which is a high-risk factor for varicella-zoster virus (VZV) infection and severe varicella. Patients with varicella who suddenly develop abdominal pain should be informed about visceral disseminated VZV infection, which principally manifests as severe abdominal pain, with potential stomach, intestine and spleen involvement. Furthermore, abdominal pain may appear several days before skin rashes, and such infections may be misdiagnosed for other acute abdomen, lupus mesenteric vasculitis or thromboembolic diseases. Thus, prompt and accurate diagnosis and the early initiation of antiviral therapy are particularly important for avoiding severe life-threatening complications.

- Citation: Zhao J, Tian M. Systemic lupus erythematosus with visceral varicella: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(25): 9168-9175

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i25/9168.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i25.9168

Systemic lupus erythaematosus (SLE) is an autoimmune disease that involves multiple systems of the body. Intestinal and mesenteric vasculitis frequently occurs in SLE patients with digestive system involvement. Studies have demonstrated that some cases may be complicated by acute abdomen, such as pancreatitis, intestinal necrosis or intestinal infarction. Varicella-zoster virus (VZV), a human alpha herpes virus of the Varicellovirus genus, causes varicella and herpes zoster. Autoimmune diseases, immune disorders and/or use of immune modulators are high-risk factors for VZV infection and induction of severe varicella. In some patients, varicella initially manifests as severe abdominal pain with potential stomach, intestine and spleen involvement. In some varicella patients, severe abdominal pain is the first presentation, and the stomach, intestines, and spleen may be involved. When these patients have SLE, it is difficult to differentiate varicella from intestinal wall and mesenteric vasculitis, which makes diagnosis and treatment difficult.

A 16-year-old female patient diagnosed with SLE 5 years prior was admitted to our hospital due to a 2-d history of intermittent abdominal pain accompanied by fever without obvious inducement.

Five years previously, the patient presented with fever, cough and expectoration after catching a cold, which was accompanied by skin petechiae and ecchymoses in the distal extremities. After receiving an infusion at the local hospital (details unknown), the patient’s condition improved; therefore, the episode was considered unremarkable. Three months later, the patient experienced a relapse of the above symptoms that was associated with hair loss, photoallergy and joint pain. Laboratory test results were as follows: Urine protein, 2 +; 24-h urinary protein quantity, 2.412 g; anti-double-stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA) antibody, +++; anti-nucleosome antibody, ++; anti-histone antibody, ++; anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) (1:100), positive; ANA (1:320), positive; ANA (1:1000), weakly positive; complement C3, 0.45 g/L (reference range: 0.79-1.52 g/L); liver and kidney function, normal; and routine blood test, normal. Combined with mild mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis indicated by renal biopsy pathology, the patient was diagnosed with “SLE and lupus nephritis”. After treatment with mycophenolate mofetil (0.5 g bid), prednisone tablets (10 mg qd), hydroxychloroquine (200 mg bid) and enalapril maleate and folic acid tablets (10 mg qd), the patient’s clinical symptoms were relieved, and she was discharged. The results for several routine urine tests thereafter were as follows: Urine protein, 3 +; and 24-h urinary protein quantity, 1-3 g. After the steroid was tapered and terminated, tacrolimus (1 mg bid) was added to the original treatment plan. In the past 4 years, the patient experienced no relapse of the above symptoms; however, her urine protein failed to normalize. Two months prior, the patient experienced persistent pain with paroxysmal exacerbations in both hands and feet. Each onset lasted approximately 2-3 d and was relieved spontaneously. Physical examination showed vasculitis-like changes in the skin on both hands. Laboratory test results were as follows: Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, perinuclear anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (pANCA) +; creatinine (Cr), 105 µmol/L (reference range: 30-90 µmol/L); urine protein, 3 +; urinary occult blood, 1 +; erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), 49 mm/h (reference range: < 38 mm/h); C-reactive protein (CRP), 29.9 mg/L (reference range: 0.068-8.2 mg/L); complement C3, 0.66 g/L; and haemoglobin (Hb), 86 g/L (reference range: 115-150 g/L). Chest computed tomography (CT) indicated bilateral interstitial pneumonia. Renal biopsy-proven active class IV lupus nephritis and cutaneous vasculitis were considered. Considering the presentation of abnormal renal function, tacrolimus was discontinued. The patient and family members refused cyclophosphamide. Then, targeted therapy with belimumab was given on the basis of steroids and mycophenolate mofetil. Her extremity pain was alleviated after treatment, and she was discharged. Treatment with prednisone tablets (50 mg qd), mycophenolate mofetil (0.5 g bid) and intravenous injection of belimumab (360 mg 1/mo) was continued at home. Two days prior, the patient was admitted to our hospital due to a 2-d history of intermittent abdominal pain accompanied by fever without obvious inducement. The primary symptom was whole-abdominal pain, especially in the upper abdomen, presenting as colic, occasionally involving the waist, back and buttocks and lasting from tens of minutes to several hours. Self-administration of acid-reducing agents had no effect, and her body temperature ranged from 35.9 °C to 38.5 °C. There was no oedema, oral ulcer, photoallergy, cough, expectoration or diarrhoea, and her urine and stool were normal.

The patient had whole-abdomen tenderness, particularly in the upper abdomen, without rebound pain or muscle tension. Two days after admission, a small amount of tufted herpes appeared in the labia majora and minora and pharynx, and the patient developed fever with a maximum body temperature of 39 °C (axillary temperature), which was accompanied by ocular hyperaemia, light bloody tears, and oral, nasal and vaginal bleeding. Four days after admission, numerous vesicular herpes and small pustules appeared on her entire body, some of which fused into flakes, and the patient exhibited tachypnoea in the decubitus position with a high pillow and uncontrolled blood pressure and oxygen saturation under oxygen inhalation. A large number of wet rales were heard in both lungs, and low-pitched breath sounds were heard in the lower lobes of both lungs.

Laboratory test results are provided in Tables 1 and 2.

| Item | Before treatment | During treatment | After treatment | Reference range |

| WBC (× 109/L) | 20.61 | 10.64 | 6.42 | 3.5-9.5 |

| NEUT (× 109/L) | 14.84 | 9.23 | 3.02 | 1.8-6.3 |

| ALC (× 109/L) | 4.74 | 0.82 | 1.93 | 1.1-3.2 |

| RBC (× 1012/L) | 3.3 | 2.54 | 3.15 | 3.8-5.1 |

| Hb (g/L) | 103 | 80 | 97 | 115-150 |

| PLT (× 109/L) | 245 | 27 | 306 | 100-300 |

| IgG (g/L) | 3.68 | / | 6.03 | 7.51-15.60 |

| C3 (g/L) | 0.47 | / | 0.44 | 0.79-1.52 |

| C4 (g/L) | 0.075 | / | 0.072 | 0.16-0.38 |

| ALT (U/L) | 47 | 656 | 12 | 7-40 |

| AST (U/L) | 65 | 836 | 34 | 13-35 |

| Alb (g/L) | 31.5 | 20.9 | 37.4 | 40-55 |

| Cr (µmol/L) | 75 | 67 | 58 | 30-90 |

| Urinary occult blood | ++ | +++ | + | - |

| Urine protein | +++ | +++ | +++ | - |

| 24-h urinary protein quantity (g/24-h) | 2.8 | / | 0.44 | - |

| ANA | 1:320 | 1:320 | - | - |

| D-D (µg/mL) | 0.64 | 25.5 | 3.03 | < 0.5 |

| Anti-RNP | + | + | / | - |

| Anti-dsDNA | - | - | / | - |

| Anti-Sm | - | - | / | - |

| Anti-RO-52 | + | + | / | - |

| ESR (mm/h) | 2 | 56 | 2 | < 38 |

| CRP (g/L) | 2.7 | 84.2 | 3.7 | 0.68-8.20 |

| Blood/urine amylase | - | / | / | - |

| ANCA | - | / | / | - |

| VZV-DNA | + | / | / | - |

| Blood culture | Gram-positive bacterium | Staphylococcus aureus | - | - |

| Item | Before treatment | After treatment | Reference range |

| Appearance | Red and turbid | Yellowish and transparent | Yellowish and clear |

| Rivalta’s test | + | - | - |

| Total cell count (× 106/L) | 6480 | 440 | - |

| Nucleated cell count (× 106/L) | 810 | 110 | < 300 |

| Proportion of neutrophils (%) | 10 | - | - |

| Proportion of lymphocytes (%) | 54 | - | - |

| Proportion of mesothelial cells (%) | 32 | - | - |

| Proportion of macrophages (%) | 4 | - | - |

| Alb (g/L) | 20.3 | 29.8 | < 25 |

| Glucose (mmol/L) | 5.04 | 7.68 | 3.6-5.5 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (U/L) | 173 | 213 | 0-200 |

| Adenosine dehydrogenase (U/L) | 4.68 | 10.63 | 0-45 |

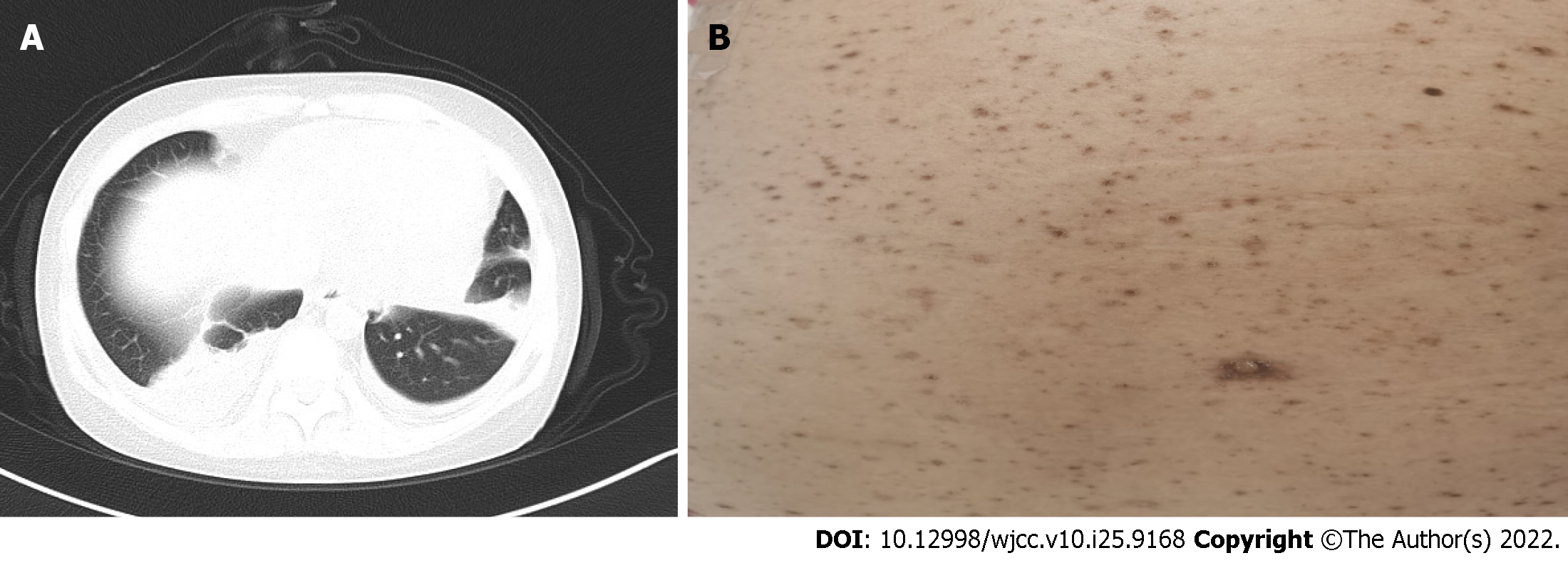

Whole-abdomen CT + contrast-enhanced scanning and CT angiography of the kidney were normal. Gastroscopy indicated chronic gastritis. Chest CT indicated bilateral pneumonia, bilateral pleural effusion and pericardial effusion (Figure 1A).

The final diagnosis was severe pneumonia complicated with parapneumonic effusion, septic shock, multi-organ failure, disseminated varicella infection, SLE, and lupus nephritis.

The patient was administered antiviral (acyclovir), immunomodulatory (intravenous injection of human immunoglobulin), anti-infection (meropenem and vancomycin) and anti-inflammatory (methylprednisolone, 40 mg qd) therapies, intermittent transfusion of platelets for the prevention and treatment of bleeding, and symptomatic and supportive treatments, including life support, closed thoracic drainage, liver protection, and fluid replacement.

After treatment for 12 d in the ICU, the patient’s condition gradually improved. The patient was removed from the ventilator and transferred to the general ward. Laboratory tests showed impro

SLE is an autoimmune disease that involves multiple systems, and digestive system involvement usually manifests as intestinal wall and mesenteric vasculitis, mainly involving the small arteries or venules of the jejunum and ileum. In general, gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, anorexia, and abdominal pain are nonspecific[1]. Endoscopy is able to reveal intestinal oedema, congestion or ischaemia with or without obstruction, with vascular inflammation and necrosis as pathological changes[2]. Although serological and inflammatory markers are considered to be nonspecific, contrast-enhanced abdominal CT is of great value for the diagnosis of SLE-related mesenteric vasculitis[3]. In clinical practice, some cases of SLE are complicated by severe acute abdomen (e.g., pancreatitis, peritonitis, and intestinal infarction), as reported in several studies[4-6].

In addition to the above diseases, long-term use of steroids and immunosuppressive agents for the treatment of SLE may decrease immunity, which is a high-risk factor for VZV infection and subsequent progression to severe varicella. The initial manifestation in the patient in this case study was abdominal pain; therefore, SLE complicated with gastrointestinal vasculitis or acute abdomen was first considered. After these conditions were ruled out by relevant examinations and after typical skin rashes appeared, varicella was ascertained with the assistance of the Department of Dermatology and the Department of Infection. Her abdominal pain resolved after the administration of antiviral therapy for 2 d. Patients with varicella should be informed about the sudden development of abdominal pain and the possibility of visceral disseminated VZV infection, which principally presents as severe abdominal pain, with potential stomach, intestine and spleen involvement[7]. Moreover, abdominal pain may appear several days before skin rashes, resulting in misdiagnosis as other acute abdomen, lupus mesenteric vasculitis or thromboembolic diseases. Visceral disseminated varicella-induced abdominal pain is attributed to the proliferation of VZV in the abdominal cavity and mesenteric ganglia, but the specific mechanism remains unclear[8-11]. Furthermore, VZV infection may be accompanied by vasculitis, presenting as abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhoea and intestinal obstruction when infection occurs in the abdominal blood vessels[12,13].

VZV infection occurs mostly in children but rarely in adults. Nonetheless, adult patients who experience VZV infection often present severe symptoms and complications. Varicella pneumonia is the most common complication of VZV infection in adults, but there are also clinical reports on acute liver failure and thrombocytopenia involving the blood system[14,15]. For the patient in this case study, no relevant antibodies were present in the body because of the lack of regular vaccination during childhood. Overall, long-term application of steroids and immunosuppressive agents for SLE treatment may have led to decreased immunity, and there was a recent history of contact with varicella patients, all of which resulted in varicella. In addition to numerous herpes lesions on the body and pharyngeal isthmus, the patient presented secondary acute liver injury, thrombocytopaenia, severe pneumonia, and uncontrolled respiratory and circulatory functions; therefore, her condition was extremely critical. Due to emotional stress among family members, photographs were not taken when the patient was critically ill; residual skin pigmentation after numerous herpes lesions was photographically recorded at discharge (Figure 1B).

Currently, there is a lack of definite recommendations for the treatment of SLE with severe varicella, but varicella infection following organ or stem cell transplantation has already been reported. With corresponding therapeutic experience as the reference, the following aspects should be taken into account for treating severe varicella in critically ill patients with rapidly progressive disease: (1) Given that maintaining respiratory and circulatory stability is the premise for successful rescue, life support must be a priority; (2) early addition of antiviral drugs contributes to reducing tissue injury and diminishing or even preventing the destruction of affected ganglion cells[16]. In general, antiviral therapy should be continued until all rashes have dried and organ symptoms have resolved; (3) in the presence of severe complications, intravenous injection of human immunoglobulin can be used to control virus invasion and suppress toxaemia-related antibodies, exerting a synergistic effect with antiviral drugs in the clinical treatment of varicella[17]; (4) glucocorticoids repress synthesis of interferon in the reticuloendothelial system, thus lowering the number of WBCs involved in phagocytosis and facilitating proliferation and spread of the virus in the body. Hence, glucocorticoid therapy is not recommended for mild VZV infection but for patients with severe pneumonia complications. Administration of methylprednisolone sodium succinate can reduce inflammatory reactions, suppress release of inflammatory mediators and cytokines and diminish exudation, thus achieving favourable curative effects[18]; (5) complications should be actively prevented and treated; and (6) the varicella-zoster vaccine should be considered for patients with autoimmune inflammatory rheumatism[19].

Yamada et al[20] reported a patient with VZV infection after living-donor liver transplantation. The patient was given methylprednisolone, tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetil after transplantation, but 12 mo later, fever and back pain with systemic vesicular rashes appeared, followed by severe pneumonia, serious liver injury and disseminated intravascular coagulation. VZV-DNA PCR indicated VZV infection; the patient was administered antiviral (intravenous injection of acyclovir), anti-infective, immunomodulatory (intravenous injection of human immunoglobulin), anti-inflammatory (steroid), respiratory and circulatory support and symptomatic support therapies. When the clinical symptoms were relieved, immunosuppressive therapy with methylprednisolone and tacrolimus was reinitiated. However, the VZV-DNA level remained quite high, even after all rashes and organ symptoms had completely subsided. Hence, prophylactic oral acyclovir was provided and discontinued until monitoring indicated a marked decline in VZV-DNA. The 6-mo follow-up showed no recurrence[20].

According to Doki et al[21], 20 of 2411 patients show visceral VZV infection within 103-800 d after allogeneic stem cell transplantation in our hospital, with 17 receiving immunosuppressive therapy when varicella appeared and 80% complaining of abdominal pain. After treatment with acyclovir, 18 patients survived, though 2 died. From this, it can be seen that although the incidence rate of visceral VZV infection is not high, it is a serious disease. Furthermore, potential visceral VZV infection and early treatment should be taken into account when abdominal pain appears in patients administered immunosuppressive agents[21].

The timing of reinitiating immunosuppressive agents for controlling SLE remains obscure, and no definite therapeutic evidence has been reported. Previous literature on VZV infection after renal transplantation has suggested that if immunosuppressive agents cannot be discontinued, such agents should be replaced with cyclosporine, azathioprine and prednisone[22]; mycophenolate mofetil may increase the incidence rate of severe varicella[23]. If high-dose steroids such as mycophenolate mofetil and cyclophosphamide are required because of disease conditions, herpes zoster virus reactivation should be strongly suspected. Specifically, elevated VZV-IgM and VZV-DNA without clinical sym

In conclusion, the incidence rate of SLE accompanied by visceral varicella with abdominal pain as the initial presentation is low, but its onset can lead to rapid disease progression with the potential of severe complications. Therefore, prompt diagnosis and early antiviral therapy are vital to prevent severe life-threatening complications.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Rheumatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A, A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Ozden F, Turkey; Sharaf MM, Syria; Tajiri K, Japan S-Editor: Chen YL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Chen YL

| 1. | Lee CK, Ahn MS, Lee EY, Shin JH, Cho YS, Ha HK, Yoo B, Moon HB. Acute abdominal pain in systemic lupus erythematosus: focus on lupus enteritis (gastrointestinal vasculitis). Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61:547-550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Janssens P, Arnaud L, Galicier L, Mathian A, Hie M, Sene D, Haroche J, Veyssier-Belot C, Huynh-Charlier I, Grenier PA, Piette JC, Amoura Z. Lupus enteritis: from clinical findings to therapeutic management. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Brewer BN, Kamen DL. Gastrointestinal and Hepatic Disease in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2018;44:165-175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | El Qadiry R, Bourrahouat A, Aitsab I, Sbihi M, Mouaffak Y, Moussair FZ, Younous S. Systemic Lupus Erythematosus-Related Pancreatitis in Children: Severe and Lethal Form. Case Rep Pediatr. 2018;2018:4612754. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kheyri Z, Laripour A, Ala M. Peritonitis as the first presentation of systemic lupus erythematous: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2021;15:611. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | White S, Merrie A. Recurrent bowel infarction in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. N Z Med J. 2003;116:U483. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Furuto Y, Kawamura M, Namikawa A, Takahashi H, Shibuya Y. Successful management of visceral disseminated varicella zoster virus infection during treatment of membranous nephropathy: a case report. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19:625. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Chen JJ, Gershon AA, Li Z, Cowles RA, Gershon MD. Varicella zoster virus (VZV) infects and establishes latency in enteric neurons. J Neurovirol. 2011;17:578-589. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Serris A, Michot JM, Fourn E, Le Bras P, Dollat M, Hirsch G, Pallier C, Carbonnel F, Tertian G, Lambotte O. [Disseminated varicella-zoster virus infection with hemorrhagic gastritis during the course of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: case report and literature review]. Rev Med Interne. 2014;35:337-340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Chang AE, Young NA, Reddick RL, Orenstein JM, Hosea SW, Katz P, Brennan MF. Small bowel obstruction as a complication of disseminated varicella-zoster infection. Surgery. 1978;83:371-374. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Au WY, Ma SY, Cheng VC, Ooi CG, Lie AK. Disseminated zoster, hyponatraemia, severe abdominal pain and leukaemia relapse: recognition of a new clinical quartet after bone marrow transplantation. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:862-865. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Abendroth A, Slobedman B. Varicella-Zoster Virus and Giant Cell Arteritis. J Infect Dis. 2021;223:4-6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Gilden D, White T, Boyer PJ, Galetta KM, Hedley-Whyte ET, Frank M, Holmes D, Nagel MA. Varicella Zoster Virus Infection in Granulomatous Arteritis of the Aorta. J Infect Dis. 2016;213:1866-1871. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Muraoka H, Tokeshi S, Abe H, Miyahara Y, Uchimura Y, Noguchi S, Sata M, Tanikawa K. Two cases of adult varicella accompanied by hepatic dysfunction. Kansenshogaku Zasshi. 1998;72:418-423. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Shibusawa M, Motomura S, Hidai H, Tsutsumi H, Fujita A. Varicella infection complicated by marked thrombocytopenia. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2014;67:292-294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Sauerbrei A. Diagnosis, antiviral therapy, and prophylaxis of varicella-zoster virus infections. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2016;35:723-734. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Lu YC, Fan HC, Wang CC, Cheng SN. Concomitant use of acyclovir and intravenous immunoglobulin rescues an immunocompromised child with disseminated varicella caused multiple organ failure. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2011;33:e350-e351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Anwar SK, Masoodi I, Alfaifi A, Hussain S, Sirwal IA. Combining corticosteroids and acyclovir in the management of varicella pneumonia: a prospective study. Antivir Ther. 2014;19:221-224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Rondaan C, de Haan A, Horst G, Hempel JC, van Leer C, Bos NA, van Assen S, Bijl M, Westra J. Altered cellular and humoral immunity to varicella-zoster virus in patients with autoimmune diseases. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66:3122-3128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Yamada N, Sanada Y, Okada N, Wakiya T, Ihara Y, Urahashi T, Mizuta K. Successful rescue of disseminated varicella infection with multiple organ failure in a pediatric living donor liver transplant recipient: a case report and literature review. Virol J. 2015;12:91. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Doki N, Miyawaki S, Tanaka M, Kudo D, Wake A, Oshima K, Fujita H, Uehara T, Hyo R, Mori T, Takahashi S, Okamoto S, Sakamaki H; Kanto Study Group for Cell Therapy. Visceral varicella zoster virus infection after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Transpl Infect Dis. 2013;15:314-318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kaul A, Sharma RK, Bhadhuria D, Gupta A, Prasad N. Chickenpox infection after renal transplantation. Clin Kidney J. 2012;5:203-206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Habuka M, Wada Y, Kurosawa Y, Yamamoto S, Tani Y, Ohashi R, Ajioka Y, Nakano M, Narita I. Fatal visceral disseminated varicella zoster infection during initial remission induction therapy in a patient with lupus nephritis and rheumatoid arthritis-possible association with mycophenolate mofetil and high-dose glucocorticoid therapy: a case report. BMC Res Notes. 2018;11:165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Rondaan C, van Leer CC, van Assen S, Bootsma H, de Leeuw K, Arends S, Bos NA, Westra J. Longitudinal analysis of varicella-zoster virus-specific antibodies in systemic lupus erythematosus: No association with subclinical viral reactivations or lupus disease activity. Lupus. 2018;27:1271-1278. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Cradock-Watson JE, Ridehalgh MK, Bourne MS. Specific immunoglobulin responses after varicella and herpes zoster. J Hyg (Lond). 1979;82:319-336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |