Published online Sep 6, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i25.8980

Peer-review started: March 29, 2022

First decision: June 16, 2022

Revised: June 22, 2022

Accepted: July 21, 2022

Article in press: July 21, 2022

Published online: September 6, 2022

Processing time: 150 Days and 6.1 Hours

Maxillofacial deformities are skeletal discrepancies that cause occlusal, functional, and esthetic problems, and are managed by multi-disciplinary treatment, including careful orthodontic, surgical, and periodontal evaluations. However, thin periodontal phenotype is often overlooked although it affects the therapeutic outcome. Gingival augmentation and periodontal accelerated osteogenic orthodontics (PAOO) can effectively modify the periodontal phenotype and improve treatment outcome. We describe the multi-disciplinary approaches used to manage a case of skeletal Class III malocclusion and facial asymmetry, with thin periodontal phenotype limiting the correction of deformity.

A patient with facial asymmetry and weakness in chewing had been treated with orthodontic camouflage, but the treatment outcome was not satisfactory. After examination, gingiva augmentation and PAOO were performed to increase the volume of both the gingiva and the alveolar bone to allow further tooth move

In patients with dentofacial deformities and a thin periodontal phenotype, multi-disciplinary treatment that includes PAOO could be effective, and could improve both the quality and safety of orthodontic-orthognathic therapy.

Core Tip: This report describes the comprehensive management of a patient with skeletal Class III malocclusion and facial asymmetry. For such cases, it is critical to evaluate the patient’s chief complaints, skeletal as well as soft tissue problems. This case highlighted the importance and benefits of periodontal phenotype modification, which can prevent complications such as attachment loss of anterior teeth that compromise the treatment outcome. Corticotomy combined bone augmentation with or without gingiva augmentation, can not only increase the safety of treatment, but also stretch the limits of deformity correction.

- Citation: Liu JY, Li GF, Tang Y, Yan FH, Tan BC. Multi-disciplinary treatment of maxillofacial skeletal deformities by orthognathic surgery combined with periodontal phenotype modification: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(25): 8980-8989

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i25/8980.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i25.8980

Maxillofacial skeletal deformities may result in malocclusion, impaired masticatory function, temporomandibular joint disorders, as well as cosmetic and psychological problems. With regard to adults with skeletal malocclusion, the treatment is limited to orthodontic camouflage or orthognathic surgery combined with orthodontic treatment, depending on the severity of the deformity[1,2]. The correction of hard tissue deformities and the maintenance of soft tissue stability are both highly important. However, various complications can occur, especially when the reposition of skeletal or dental components is closed to or beyond physical limitations[3].

The periodontal phenotype is an essential factor associated with the success of treatment for maxillofacial skeletal deformities, but it is often overlooked. The periodontal phenotype is defined by the gingival phenotype and bone morphotypes, which are based on the three-dimensional gingival volume and bone plate thickness, respectively[4]. In patients with a thin periodontal biotype who are under orthodontic treatment, bone dehiscence and gingival recession (GR) are common[5]. GR is associated with a risk of further periodontal breakdown and may worsen the treatment outcome, especially in cases where the teeth are exposed to orthodontic forces that shift the dentition outside of the alveolar bone[5]. Mota de Paulo et al[6] reported that GR of 0.5-3 mm was common in patients undergoing orthodontic-orthognathic treatment. However, no clear association has been established between orthodontic-orthognathic treatment and GR[7]. Therefore, the position of teeth and periodontal phenotype must be evaluated carefully before any treatment is initiated.

The overall therapeutic goals of orthodontic treatment are to improve musculoskeletal, dento-osseous, soft tissue relationships, masticatory function, and occlusion, as well as to maintain dental and periodontal health, psychological well-being, and long-term stability[1]. Therefore, given these complex therapeutic goals, the management of dentofacial deformities is challenging and requires the collaboration of a multi-disciplinary team. In this study, we present a 22-year-old patient with Class III malocclusion, facial asymmetry and thin periodontal phenotype who underwent successful multi-disciplinary treatment. We hope this case will focus attention on periodontal phenotype in the treatment of dentofacial deformities, and guide clinicians in case management when the correction is limited by periodontal tissue volume.

A 22-year-old woman attended the Department of Periodontology, Nanjing Stomatological Hospital. Her chief complaints were facial asymmetry and weakness in chewing that she had been experiencing for 10 years.

The patient was systemically healthy, but had facial imbalance for several years. She had previously undergone orthodontic camouflage to improve her facial appearance, but the outcome was disappointing. Four premolars, one in each quarter, had been extracted.

The patient denied having a history of any related illness.

The patient denied having any relevant personal or family history.

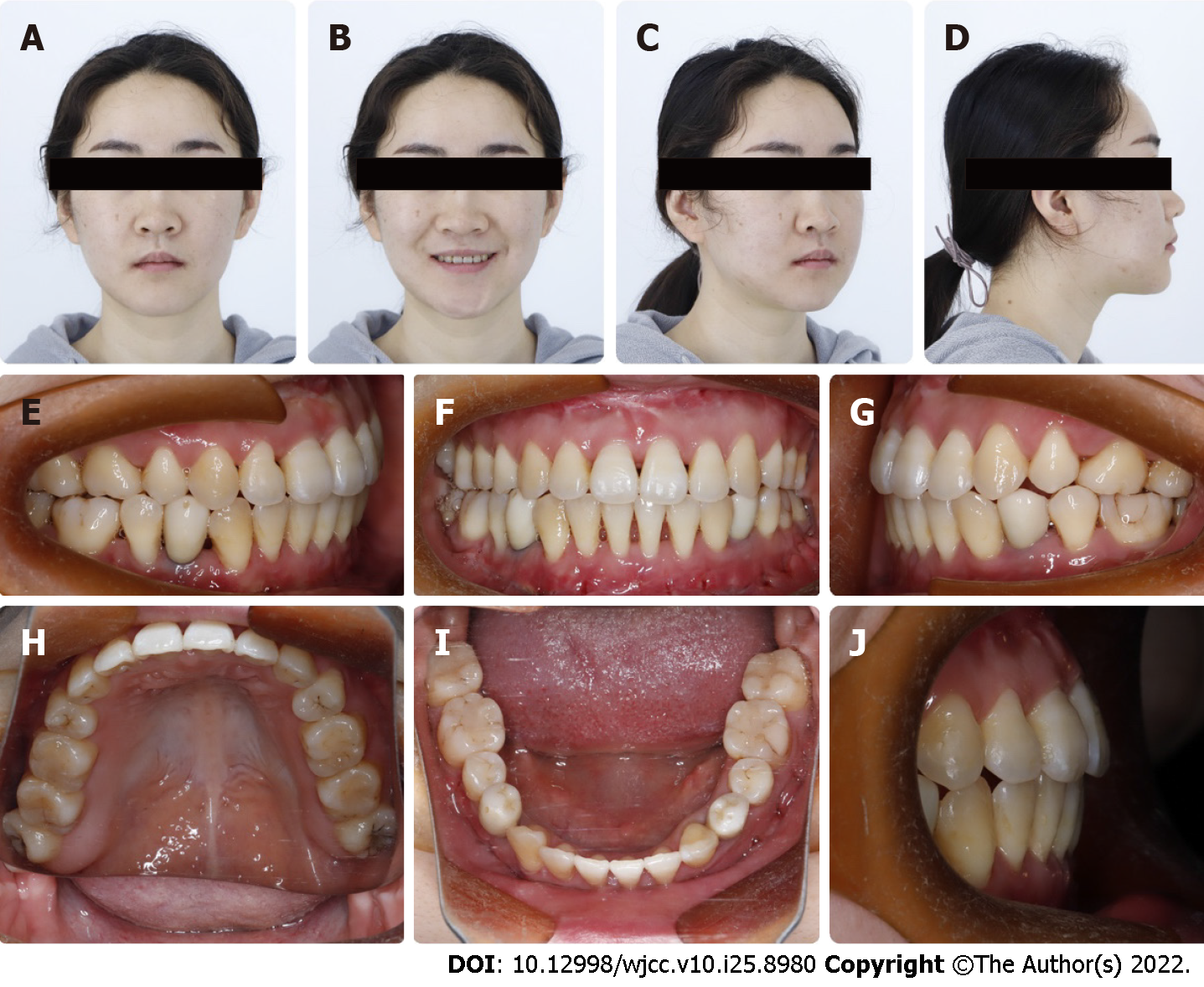

Extraoral examination showed facial asymmetry where the midpoint of the lower lip and chin were to the right of the facial midline (Figure 1A-D). Intraoral examination indicated good oral hygiene, GR, thin gingival biotype, and malocclusion, including Angle Class II molar and canine relationship on the right side, Angle Class III relationship on the left side, and crossbite (from 12 to 14) (Figure 1E–J). No clicking or pain was detected during mandibular movement.

The results of all blood tests, including complete blood count, biochemical examination such as calcium, Vitamin D level, liver function, blood glucose, blood lipids and uric acid were normal.

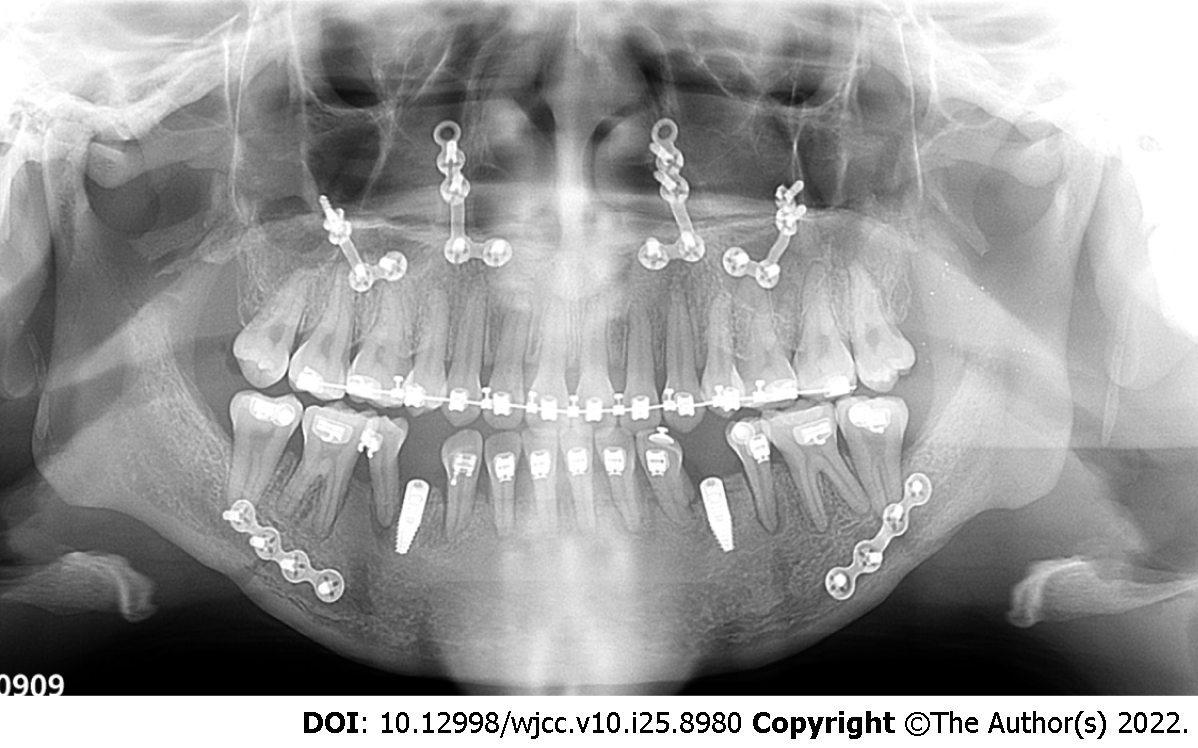

Cone-beam computed tomography showed insufficient alveolar bone cover on the facial side of anterior incisors (Figure 2). Cephalometric summary indicated skeletal Class III malocclusion (ANB angle, -2.2), proclination of upper incisors (U1-NA angle, 33.7), lingual inclination of lower incisors (L1-NB angle, 15.5°) and soft tissue imbalance (Upper lip to E-plane, -4.1 mm) (Figure 3).

Based on the findings of the examinations conducted, the patient was diagnosed with mandibular asymmetry, skeletal Class III malocclusion with partial denture crossbite and generalized mild gingival recession.

Treatment of plaque control and non-surgical periodontal treatment was initiated. Considering that advanced attachment loss could occur due to orthodontic decompensation, gingiva augmentation was performed with Mucograft (Geistlich, Switzerland) to increase soft tissue thickness from #33 to #43, via the minimally invasive tunnel technique (Figure 4).

Periodontal accelerated osteogenic orthodontics (PAOO) is a procedure that combines corticotomy with bone grafting and is effective for modifying the morphotype of the alveolar bone[4]. In the present case, before the initiation of orthodontic treatment, PAOO was performed to increase alveolar bone thickness on the labial side from #33 to #43, while simultaneously increasing the speed of teeth movement (Figure 5). After the full-thickness flap was elevated, bone dehiscence at the lower incisors could be clearly observed. Briefly, a piezo knife was used to create vertical interproximal alveolar decortication below the alveolar crest to a depth of 3 mm. Next, bone-derived material was grafted on the labial side of the decorticated alveolar bone, with an absorbable barrier membrane used to cover the bone grafts (Bio-Oss, Geistlich, Switzerland).

For the 14-mo preoperative orthodontic treatment, a self-ligating 0.022 × 0.028-in slot appliance system (Damon Q; Ormco; Kavo; United States) was applied to both arches. Presurgical dental alignment and leveling were achieved with sequential nickel-titanium archwires: briefly, 0.018 × 0.025-inch stainless steel archwires were placed in both arches to re-open the space for #34 and #44. The space for the premolar in each mandibular quarter was reserved for future restoration. Class II elastics (1/4 inch, 3.5 oz; Ormco, United States) were used for mandibular incisor proclination. As a result of soft and hard tissue augmentation, the gingival margin of the mandibular incisors was maintained at a similar level after orthodontic decompensation (Figure 6).

The following presurgical cephalometric measurements were obtained: SNA angle, 76.5°; SNB angle, 80.4°; ANB angle, -4°; U1-SN angle, 105°; L1-MP angle, 95°; S-GO, 73.85 mm; SN-MP angle, 37°; N-ANS, 52.38 mm; ANS-ME, 62 mm; upper lip to E-plane, -3.5 mm; lower lip to E-plane, 5 mm; crossbite, 8 mm. The maxilla was 1 mm to the right of the facial midline, and the mandible was 4 mm to the right of the midline. The occlusal plane on the left was 3 mm superior to the right side. Based on these observations, Le Fort I osteotomy was performed to reposition the maxilla 5 mm forward and 1 mm to the left with clockwise rotation. This was combined with bilateral sagittal split osteotomy to achieve mandible setback of 6.5 mm (Figure 7). After surgery, the re-established jaw relationship was fixed for 4 wk via an occlusal splint.

Optimal occlusion was achieved after postoperative orthodontic therapy which lasted approximately 8 mo until an optimal occlusion was obtained. Asymmetry elastics (3/16 inch, 3.5 oz; Ormco, United States) were used to achieve the coordinate midline and class I canine relationship. Implants were placed at the space reserved for #34 and #44 at 4 mo after orthognathic surgery (Figure 8).

To further improve facial symmetry and lateral profile, the patient underwent genioplasty to reposition the chin forward by 5 mm and left by 2.5 mm, as well as to descend the left side of the chin by 1.5 mm.

The comprehensive multi-disciplinary treatment lasted for more than 2 years (Table 1), and the outcome was satisfying to both the patient and the clinicians. The patient’s facial asymmetry was corrected; occlusion was improved; the relationship between the teeth and alveolar bone was improved; and the structure of the maxilla-mandibular complex was improved (Figure 9). The gingiva did not show further recession compared to the condition before treatment; this was indicative of long-term periodontal stability and oral health.

| Time (mo/yr) | Procedures |

| October, 2018 | Initial visit |

| November, 2018 | Gingiva augmentation |

| March, 2019 | PAOO and pre-operative orthodontic treatment |

| April, 2020 | Orthognathic surgery |

| June, 2020 | Implants placement and post-operative orthodontic treatment |

| April, 2021 | Genioplasty |

In this report, we describe the successful multi-disciplinary treatment of a case of maxillofacial abnormality with a challenging periodontal phenotype. Although the periodontal phenotype affects the outcome of treatment, such as orthodontic camouflage and orthognathic surgery, which are typically performed in such cases, it is often overlooked during treatment decision-making. The findings in the present case highlight the limitation stretch brought by periodontal phenotype modification.

Although orthodontic camouflage can improve facial appearance, it has little effect on mandibular asymmetry. This is evident from the failure of orthodontic camouflage in the present case. A retrospective study reported that a Holdaway angle greater than 10.3° and Wits appraisal less than -5.8 mm are critical prognostic parameters for surgery, based on which over 80% of 65 cases could be successfully classified[8]. Furthermore, skeletal Class III malocclusion observed in the present case is one of the indicators of the need for surgery[8]. Accordingly, it has been reported that surgical intervention is necessary for the correction of mandibular asymmetry and chin morphology in adults[1]. With regard to the present patient, the disharmony of the maxilla-mandibular complex was corrected by mandibular setback, maxillary advancement, and rotation. With regard to stability after double-jaw surgery in Class III malocclusion, a systematic review by Mucedero et al[9] showed that surgical correction appeared to be beneficial for maxillary advancements of up to 5 mm and for the correction of presurgical sagittal intermaxillary discrepancies smaller than 7 mm. This is corroborated by the outcomes in the present case. Therefore, attention to patients’ chief complaints as well as careful examination and evaluation is a pre-requisite for successful treatment.

GR and thin periodontal biotype were major challenges in the present case. Furthermore, orthodontic decompensation in the present case meant that the lower incisors were repositioned labially and bone dehiscence had already occurred (based on the observations during PAOO). In this situation, severe complications such as further attachment loss or even loss of anterior teeth can occur, which could have resulted in the decompensation being unfeasible. Therefore, the increase in alveolar bone width, especially labial/buccal bone width via PAOO can be very helpful in such cases. In agreement with the present findings, PAOO has been used to effectively increase the width of the keratinized gingiva and labial bone thickness in Chinese patients with skeletal Class III malocclusion[10]. Similarly, Gao et al’s systematic review also showed that compared to corticotomy, PAOO resulted in a significant increase in buccal bone thickness and bone density[11]. The width of the alveolar bone process and thickness of the alveolar process are associated with GR[12,13]. The findings reported so far indicate the benefits of PAOO for orthodontic treatment. Specifically, PAOO can not only accelerate tooth movement but also potentially expand the limits of tooth movement, especially the mandibular incisors[5]. Despite these advantages of PAOO, it has limitations such as the complexity of interdisciplinary management and increased cost and treatment time. Also, it has to be noted that the procedure selection, risk evaluation and expected outcomes are to be analyzed case by case, due to the heterogeneity of each study[14]. Therefore, modification of periodontal phenotype at the appropriate time point and by case-specific method can prevent cases from failure and compromising outcomes.

When the gingiva is extremely thin, soft tissue augmentation is required as a preliminary procedure before secondary corticotomy and bone augmentation[5]. In accordance with these guidelines, gingiva augmentation followed by PAOO was performed in our case. The combination of procedures benefits the patient who had a high risk of advanced bone dehiscence and GR during orthodontic decompensation[5]. It allowed the reposition of teeth to the extent that might not be achieved without impaired gingiva and periodontal attachment. However, the present case has some limitations. For instance, the patient underwent several surgeries that entailed high cost and prolonged treatment time. Additionally, as the implants were placed close to the root of the natural teeth, monitoring of the implants is necessary. The TMJ function also requires long-term follow-up[15].

In summary, in cases with dentofacial deformities, it is important to correctly recognize skeletal discrepancies prior to treatment. Additionally, periodontal phenotype needs to be evaluated as a key factor that may determine the treatment outcome. In selected cases, corticotomy combined with soft and hard tissues augmentation can potentially expand the limits of tooth movement and avoid correction achieved at the cost of periodontal tissue breakdown.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Dentistry, oral surgery and medicine

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B, B

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: C AID, Colombia; Cavalcanti AL, Brazil; Isola G, Italy; Mesquita RA, Brazil; Rattan V, India; Ullah K, Pakistan S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: Webster JR P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Cottrell DA, Edwards SP, Gotcher JE. Surgical correction of maxillofacial skeletal deformities. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;70:e107-e136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Cavuoti S, Matarese G, Isola G, Abdolreza J, Femiano F, Perillo L. Combined orthodontic-surgical management of a transmigrated mandibular canine. Angle Orthod. 2016;86:681-691. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Bishara SE, Burkey PS, Kharouf JG. Dental and facial asymmetries: a review. Angle Orthod. 1994;64:89-98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Jepsen S, Caton JG, Albandar JM, Bissada NF, Bouchard P, Cortellini P, Demirel K, de Sanctis M, Ercoli C, Fan J, Geurs NC, Hughes FJ, Jin L, Kantarci A, Lalla E, Madianos PN, Matthews D, McGuire MK, Mills MP, Preshaw PM, Reynolds MA, Sculean A, Susin C, West NX, Yamazaki K. Periodontal manifestations of systemic diseases and developmental and acquired conditions: Consensus report of workgroup 3 of the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions. J Periodontol. 2018;89 Suppl 1:S237-S248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 152] [Cited by in RCA: 250] [Article Influence: 41.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kao RT, Curtis DA, Kim DM, Lin GH, Wang CW, Cobb CM, Hsu YT, Kan J, Velasquez D, Avila-Ortiz G, Yu SH, Mandelaris GA, Rosen PS, Evans M, Gunsolley J, Goss K, Ambruster J, Wang HL. American Academy of Periodontology best evidence consensus statement on modifying periodontal phenotype in preparation for orthodontic and restorative treatment. J Periodontol. 2020;91:289-298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Mota de Paulo JP, Herbert de Oliveira Mendes F, Gonçalves Filho RT, Marçal FF. Combined Orthodontic-Orthognathic Approach for Dentofacial Deformities as a Risk Factor for Gingival Recession: A Systematic Review. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2020;78:1682-1691. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Al-Jewair T. Orthodontic-orthognathic surgical treatment may not be a major risk factor for gingival recession. J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2021;21:101613. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Eslami S, Faber J, Fateh A, Sheikholaemmeh F, Grassia V, Jamilian A. Treatment decision in adult patients with class III malocclusion: surgery versus orthodontics. Prog Orthod. 2018;19:28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Mucedero M, Coviello A, Baccetti T, Franchi L, Cozza P. Stability factors after double-jaw surgery in Class III malocclusion. A systematic review. Angle Orthod. 2008;78:1141-1152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Li C, Cai Y, Chen S, Chen F. Classification and characterization of class III malocclusion in Chinese individuals. Head Face Med. 2016;12:31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Gao J, Nguyen T, Oberoi S, Oh H, Kapila S, Kao RT, Lin GH. The Significance of Utilizing A Corticotomy on Periodontal and Orthodontic Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Biology (Basel). 2021;10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Tepedino M, Franchi L, Fabbro O, Chimenti C. Post-orthodontic lower incisor inclination and gingival recession-a systematic review. Prog Orthod. 2018;19:17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Pernet F, Vento C, Pandis N, Kiliaridis S. Long-term evaluation of lower incisors gingival recessions after orthodontic treatment. Eur J Orthod. 2019;41:559-564. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Alvarez MA, Mejia A, Alzate D, Rey D, Ioshida M, Aristizabal JF, Rios HF, Bellaiza-Cantillo W, Tirado M, Ruellas A, Cevidanes L. Buccal bone defects and transversal tooth movement of mandibular lateral segments in patients after orthodontic treatment with and without piezocision: A case-control retrospective study. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2021;159:e233-e243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Michelotti A, Iodice G. The role of orthodontics in temporomandibular disorders. J Oral Rehabil. 2010;37:411-429. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |