Published online Sep 6, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i25.8837

Peer-review started: December 8, 2021

First decision: January 8, 2022

Revised: January 24, 2022

Accepted: June 30, 2022

Article in press: June 30, 2022

Published online: September 6, 2022

Processing time: 260 Days and 17.3 Hours

The United Kingdom government introduced lockdown restrictions for the first time on 23 March 2020 due to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. These were partially lifted on 15 June and further eased on 4 July. Changes in social behaviour, including increased alcohol consumption were described at the time. However, there were no data available to consider the impact of these changes on the number of alcohol-related disease admissions, specifically alcohol-related acute pancreatitis (AP). This study evaluated the trend of alcohol-related AP admissions at a single centre during the initial COVID-19 lockdown.

To evaluate the trend in alcohol-related AP admissions at a single centre during the initial COVID-19 lockdown in the United Kingdom.

All patients admitted with alcohol-related AP from March to September 2016 to 2020 were considered in this study. Patient demographics, their initial presen

One hundred and thirty-six patients were included in the study. The highest total number of AP admissions was seen in March–September 2019 and the highest single-month period was in March–May 2020. Admissions for first-time presentations of AP were highest in 2020 compared to other year groups and were significantly higher compared to previous years, for example, 2016 (P < 0.05). Furthermore, the rate of admissions decreased by 38.89% between March–May 2020 and June–September 2020 (P < 0.05), coinciding with the easing of lockdown restrictions. This significant decrease was not observed in the previous year groups during those same time periods. Admissions for recurrent AP were highest in 2019. The median length of hospital stay did not differ between patients from each of the year groups.

An increased number of admissions for alcohol-related AP were observed during months when lockdown restrictions were enforced; a fall in figures was noted when restrictions were eased.

Core tip: The coronavirus disease 2019 lockdowns have seen a shift in the population’s social behaviour. Studies have shown an increase in alcohol consumption in the general population over the lockdown period. A retrospective study was performed and observed a rise in alcohol-related pancreatitis admissions during the pandemic. In this context we observed higher admission numbers for alcohol-related pancreatitis during the time when restrictions were in place, and numbers reduced once restrictions were eased.

- Citation: Mak WK, Di Mauro D, Pearce E, Karran L, Myintmo A, Duckworth J, Orabi A, Lane R, Holloway S, Manzelli A, Mossadegh S. Hospital admissions from alcohol-related acute pancreatitis during the COVID-19 pandemic: A single-centre study. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(25): 8837-8843

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i25/8837.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i25.8837

Demography and emergent behaviour trends have always affected health and infectious as well as noncommunicable disease[1]. There is a strong link between patterns of alcohol consumption and various noninfectious diseases, including pancreatitis[2]. According to the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, the incidence of pancreatitis associated with alcohol use is approximately 14 per 100000 per year and is a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in the United Kingdom[3]. In susceptible persons, there is a clear association between the volume and duration of alcohol consumed and the likelihood of developing acute pancreatitis (AP)[4].

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and subsequent introduction of restrictions on daily life had a profound impact worldwide. In the United Kingdom, lockdown restrictions were first enforced on 23 March 2020. In the months that followed, increased social isolation, psychological distress and a shift in social behaviour (including increased alcohol consumption), were described in medical journals, national surveys[5,6] and in the mainstream media. Although the link between alcohol abuse and AP is well known[2,4], there are no available data as to whether potential changes in alcohol consumption over the lockdown period in the United Kingdom had an impact on incidence of disease. This study evaluated the trend in admissions for alcohol-related AP in a single centre during the first round of lockdown restrictions.

The study was registered and approved by the Royal Devon and Exeter NHS Foundation Trust Governance Board (reference number 20-4628). All patient data were fully anonymised at the time of collection and therefore individual informed consent was not required.

In order to reduce COVID-19 transmission, from 23 March 2020, the public were asked to not leave home except for exercise and essential travel. All nonessential retail sector businesses including pubs, bars and accommodation facilities were closed. Restrictions were partially lifted on 15 June and further eased on 4 July, when bars and restaurants reopened.

All patients age ≥ 18 years with a confirmed diagnosis of alcohol-related AP during March–September in the five consecutive years (2016–2020) were considered for this study. Cases between October and February, patients aged < 18 years and non-alcohol-related AP were excluded.

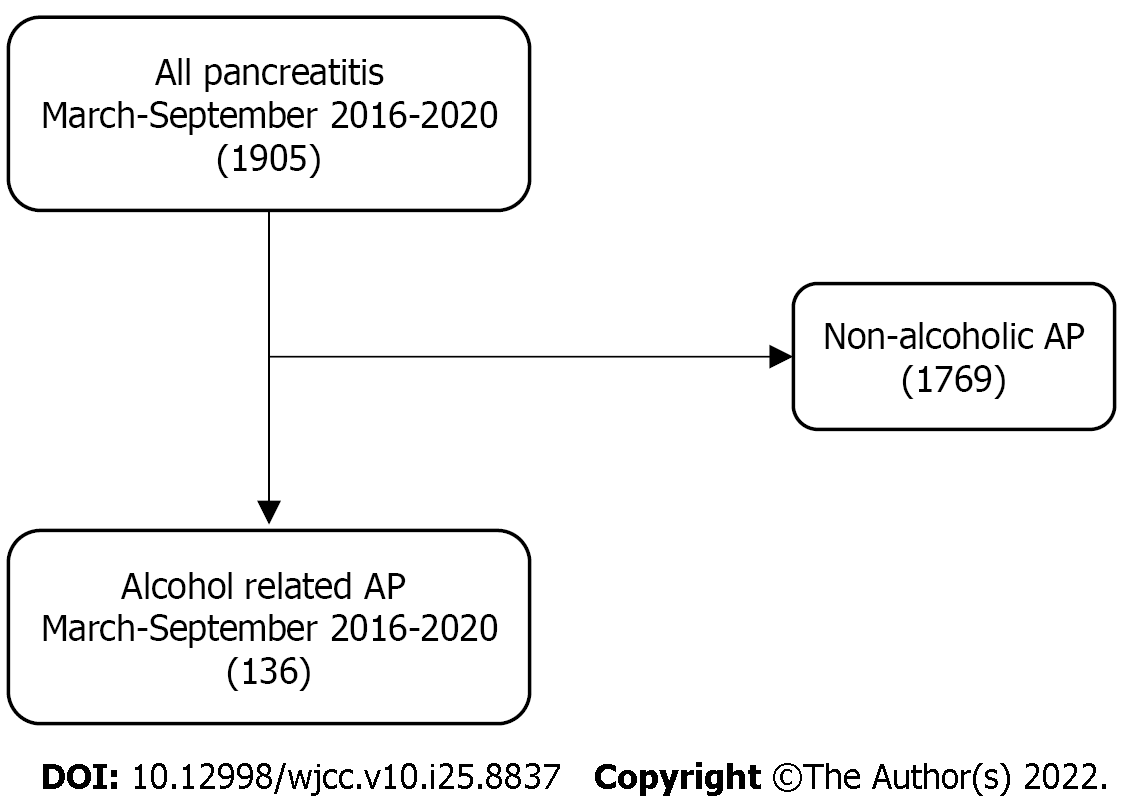

At our Institution, AP is diagnosed in the presence of at least two of the three following criteria[7]: Abdominal pain, serum amylase > 450 IU/L and radiological findings of AP. All pancreatitis cases were retrieved using the Trust’s electronic patient record system. A total of 1905 patients with any type of pancreatitis were obtained in the initial search, of which 1769 were coded as other causes of AP and 136 were coded as alcohol related (Figure 1). Patients were divided into 5-year groups (2016–2020). Patients’ demographic data, first presentations of AP, recurrent admissions, disease severity according to the revised Atlanta classification of AP[8] and length of hospital stay were assessed for each year. The period of March–May was of particular interest given that COVID-19 lockdown restrictions occurred during these months in 2020. We compared the number of first presentations and recurrent admissions in March–May and June–September for each year group.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Statistics version 20 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Continuous variables of a Gaussian distribution were described as mean ± SD. Those that were not normally distributed were given as median and interquartile range (IQR). Categorical data were defined as absolute numbers and percentages. Means were compared using one-way ANOVA. Differences in severity was evaluated with the χ2 test. Medians and absolute number of admissions were analysed with the Kruskal–Wallis test. Statistical significance was assessed at the level of P < 0.05.

A total of 136 patients were included in the analysis across all 5-year groups. There were 79 male (58%) and 57 female (42%) patients respectively. Mean age was 48 ± 14 years. Age and gender did not differ between the observed year groups (Table 1). When reviewing admission laboratory tests, there were no patients with active severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection. Analysis of serum biochemistry showed CRP as the only test with a significant difference during the study period (P = 0.0002695, Table 2); such a difference may have been coincidental as no correlation was found.

| Parameter | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | P |

| M | 9 | 18 | 19 | 21 | 14 | 0.037262 |

| F | 3 | 6 | 7 | 17 | 22 | |

| Mean age ± SD (range) | 52.0 ± 19.344 (30-87) | 47.0 ± 14.794 (19-77) | 45.0 ± 12.966 (25-67) | 46.0 ± 13.440 (25-74) | 52.0 ± 12.776 (26-85) | 0.243556 |

| Total admission | 12 | 24 | 26 | 38 | 36 | 0.022151 |

| First onset AP | 11 | 22 | 15 | 26 | 29 | 0.091681 |

| Recurrent AP | 1 | 2 | 11 | 12 | 7 | 0.020791 |

| Total admission | 12 | 24 | 26 | 38 | 36 | |

| March-May | 6 | 8 | 14 | 15 | 21 | 0.16571 |

| June-September | 6 | 16 | 12 | 23 | 15 | 0.096081 |

| First onset AP | 11 | 22 | 15 | 26 | 29 | |

| March-May | 6 | 8 | 7 | 13 | 18 | |

| June-September | 5 | 14 | 8 | 13 | 11 | |

| Disease severity (n) | 0.92622 | |||||

| Mild | 8 | 16 | 17 | 29 | 25 | |

| Moderate | 3 | 7 | 6 | 8 | 9 | |

| Severe | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | |

| Median hospital stay (IQR) | 4.5 (2.0; 7.0) | 4.5 (3.0; 9.0) | 3.00 (1.25; 5.75) | 4 (2; 6) | 3.00 (2.00; 5.25) | 0.5403171 |

| Median parameter (IQR)1 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | Overall P |

| Creatinine | 55.0 (50.5, 57.0) | 61.5 (51.5, 72.5) | 57.5 (54.0, 65.5) | 62 (53, 82) | 60.0 (54.0, 76.5) | 0.61261 |

| eGFR | 90 (90, 90) | 90 (90, 90) | 90 (90, 90) | 90 (90, 90) | 90.0 (89.5, 90.0) | 0.447051 |

| CRP | 45.5 (15.0, 185.0) | 57.50 (19.0, 212.75) | 65.0 (6.75, 93.00) | 6.0 (1.0, 30.5) | 6.50 (3.25, 13.75) | 0.00026951 |

| Hb | 133 (125, 143) | 132.5 (125.5, 146.5) | 145.0 (136.0, 151.5) | 149 (136, 159) | 138.0 (127.5, 147.0) | 0.083811 |

| White cell count | 7.00 (5.95, 11.70) | 12.05 (9.35, 14.45) | 10.30 (6.875, 15.35) | 10.2 (6.2, 13.0) | 10.7 (7.8, 12.4) | 0.21831 |

| Amylase | 286.0 (112.25, 650.00) | 158 (103, 520) | 242.0 (204.0, 463.75) | 254 (137, 433) | 382.0 (102.5, 613.5) | 0.84971 |

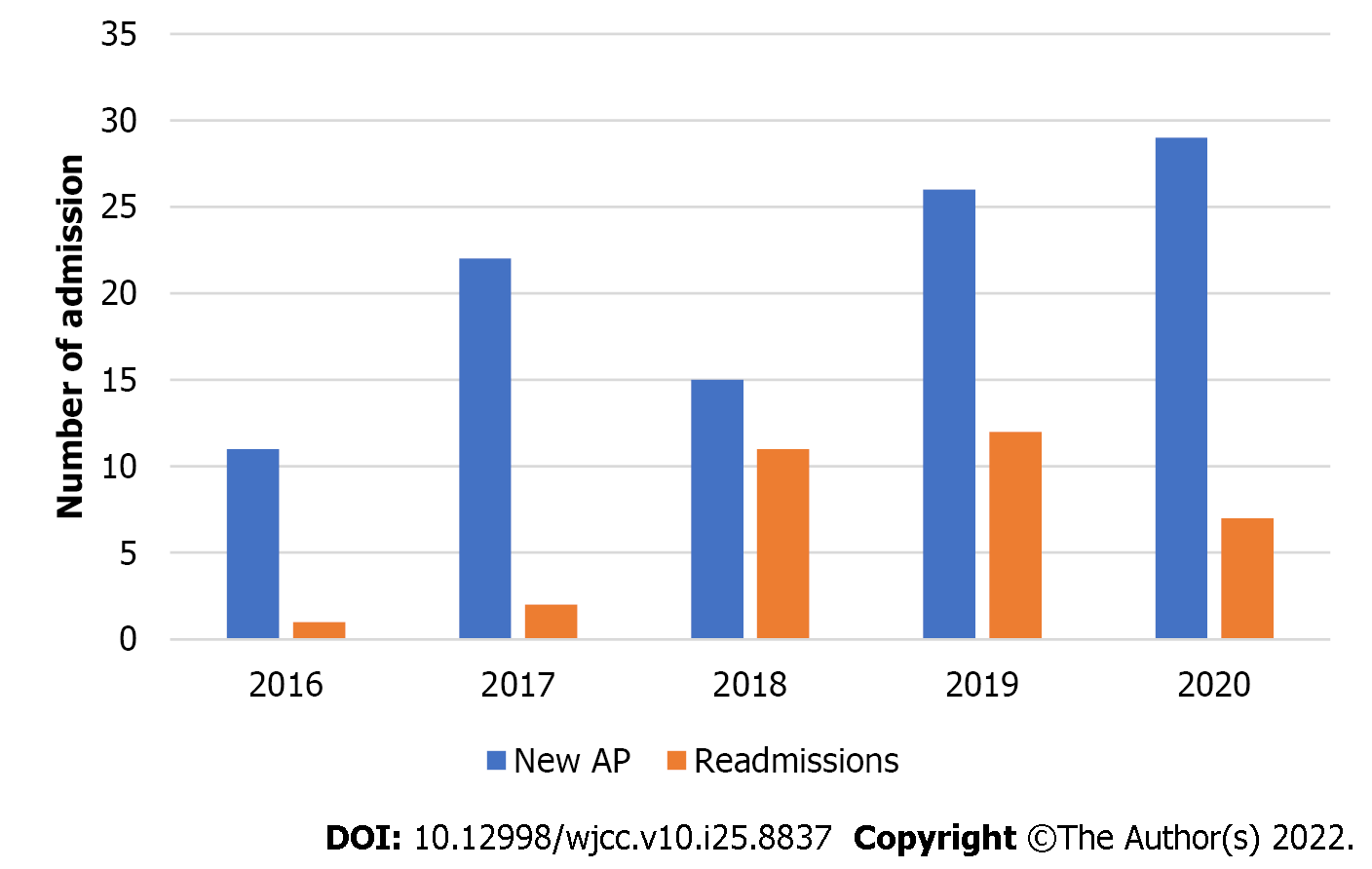

Eighty-nine (65.4%) patients were admitted with their first presentation of AP and 47 (34.6%) were recurrent admissions. The number of monthly (March–September) admissions per year was not consistent between years 2016 and 2020 (P = 0.02215, Table 1). Overall admissions per year was highest in 2019, however admissions for first-time disease onset were highest in 2020 (Table 1, Figure 2). During the lockdown period of March–June 2020, admissions were 38.5% higher than in the same period during 2019 (P = 0.3758), 157.1% higher than in 2018 (P = 0.184), 125% higher than in 2017 (P = 0.07652) and 200% higher than in 2016 (P = 0.04953).

After lockdown restrictions were eased (June–September 2020), there was a 38.89% decrease in first-time admissions compared to March–May 2020 (P = 0.03231). Such a significant decrease was not observed in previous year groups.

There were more cases of recurrent AP in 2019 compared to other year groups and significantly higher compared to 2016 (P = 0.03142, Table 1). Disease severity did not differ among groups (P = 0.92622, Table 1).

The overall median hospital stay was 4 d (IQR 2–6.25), with no significant difference between the years observed (P = 0.540317, Table 1). Median length of stay was 3 d in 2020, 4 in 2019, 3 in 2018, 4.5 in 2017, and 4.5 in 2016 (P = 0.540317, Table 1).

Since COVID-19 lockdown restrictions were first introduced in March 2020, both positive and negative behavioural changes related to alcohol consumption have been reported in the medical literature[6,9,10]. According to the results of one national survey, up to one-third of regular drinkers stated they had cut down or even stopped drinking altogether during the pandemic[11], while one in five had increased their drinking to potentially more harmful levels[12]. Since the risk of misuse is higher in people previously or currently known to have abused alcohol[9,11,13], it has been hypothesised that psychological stress, social isolation and reduced access to addiction support services during lockdown may have contributed to this behaviour[9]. Moreover, national retail sales of alcohol for private consumption (when pubs and restaurants were closed) rose by £160 million in April 2020 compared to the same time period in 2019, indicating that alcohol consumption may have increased during this time[14].

To the best of our knowledge, there are no available data on the impact of alcohol abuse on the trend of hospital admissions for alcohol-related AP during the COVID-19 pandemic. In our study, the highest number of overall admissions (both first presentations and recurrent admissions) between March and September occurred in 2019; single-month figures and the number of first-presentations alone were highest during March–May 2020, corresponding with the beginning of lockdown restrictions. The number of admissions significantly decreased between June and September of the same year when lockdown restrictions eased. Comparing the same time periods (March–May and June–September) in 2016–2019, the number of overall AP admissions were more consistent between these two periods. None of the patients admitted in 2020 had COVID-19, therefore it was not possible to speculate on the possible role of the infection on the onset of AP and admission rates. Nevertheless, it could be hypothesised that this corresponded with a decrease in alcohol consumption, as social isolation lessened and access to specialist services once again became more readily available.

Admissions for recurrent AP followed a different pattern, as overall figures were highest in 2019 and no difference in monthly admissions was observed throughout the 5-year study period. The analysis of our data could not explain such a result. There were a greater number of first presentations of AP in 2020 compared to 2019, while overall recurrent cases were higher in 2019. When examining March–May (lockdown period), the overall admissions and first presentations of AP in 2020 outweighed those of 2019.

This study was potentially limited by the short timeframe of data collection and a small cohort of patients. Moreover, assumptions have been made about alcohol consumption among a local population based on national statistics; this may have resulted in ecological fallacy. If this research were to be expanded nationally, this may allow data collection from a larger group of individuals and would avoid bias based on the behaviour of one local population.

An increased number of admissions for alcohol-related AP was observed at our centre during the months when COVID-19 lockdown restrictions were enforced, and the numbers decreased in correlation with the easing of restrictions. Follow-up studies looking at the epidemiology of postpandemic drinking habits and alcohol-related AP admission rates would allow better understanding of the effects of COVID-19 on alcohol-related AP. This could also potentially inform how community support could be improved for this group of patients.

In order to combat the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, one strategy was the intro

There are currently no data on the impact of alcohol abuse on the trend of hospital admissions for alcohol-related acute pancreatitis (AP) during the COVID-19 pandemic.

To evaluate the trend in alcohol-related AP admissions during the first COVID-19 lockdown period.

Review of case notes and discharge summaries of March–September 2016–2020.

During the lockdown period of March–June 2020, admissions were 38.5% higher than in 2019. A 38.89% reduction was observed following the easing of restrictions.

An increased number of admissions for alcohol-related AP was observed during lockdown, with cases falling following the easing of restrictions. Follow-up studies are required to better understand the effects of COVID-19 on alcohol-related AP.

Follow-up studies looking at the epidemiology of postpandemic drinking habits and alcohol-related AP admission rates would allow better understanding of the effects of COVID-19 on alcohol-related AP. This could also potentially inform how community support could be improved for this group of patients.

The statistical methods of this study were reviewed by Miss Alice Carr from Institute of Biomedical and Clinical Science, University of Exeter Medical School.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Public, environmental and occupational health

Country/Territory of origin: United Kingdom

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Rodríguez CV, United States; Tsoulfas G, Greece; Tudoran C, Romania S-Editor: Chen YL L-Editor: Kerr C P-Editor: Chen YL

| 1. | Patel V, Chisholm D, Parikh R, Charlson FJ, Degenhardt L, Dua T, Ferrari AJ, Hyman S, Laxminarayan R, Levin C, Lund C, Medina Mora ME, Petersen I, Scott J, Shidhaye R, Vijayakumar L, Thornicroft G, Whiteford H; DCP MNS Author Group. Addressing the burden of mental, neurological, and substance use disorders: key messages from Disease Control Priorities, 3rd edition. Lancet. 2016;387:1672-1685. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 434] [Cited by in RCA: 518] [Article Influence: 57.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Parry CD, Patra J, Rehm J. Alcohol consumption and non-communicable diseases: epidemiology and policy implications. Addiction. 2011;106:1718-1724. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 197] [Cited by in RCA: 191] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | National institute for Health and Care Excellence. Pancreatitis: diagnosis and management. 2018. [Cited 14 November 2021]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng104/chapter/Context. |

| 4. | Chowdhury P, Gupta P. Pathophysiology of alcoholic pancreatitis: an overview. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:7421-7427. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 5. | Arora T, Grey I. Health behaviour changes during COVID-19 and the potential consequences: A mini-review. J Health Psychol. 2020;25:1155-1163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 233] [Cited by in RCA: 188] [Article Influence: 37.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | The HRB National Drugs Library. Alcohol consumption during the Covid-19 Lockdown in the UK (FINAL). June, 2020. [Cited 14 September 2021]. Available from: https://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/32284/1/IAS_Summary_findings_alcohol_use_Covid-19_lockdown.pdf. |

| 7. | Working Party of the British Society of Gastroenterology; Association of Surgeons of Great Britain and Ireland; Pancreatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland; Association of Upper GI Surgeons of Great Britain and Ireland. UK guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis. Gut. 2005;54 Suppl 3:iii1-iii9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 184] [Cited by in RCA: 330] [Article Influence: 16.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, Gooszen HG, Johnson CD, Sarr MG, Tsiotos GG, Vege SS; Acute Pancreatitis Classification Working Group. Classification of acute pancreatitis--2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut. 2013;62:102-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4932] [Cited by in RCA: 4311] [Article Influence: 359.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (45)] |

| 9. | Kim JU, Majid A, Judge R, Crook P, Nathwani R, Selvapatt N, Lovendoski J, Manousou P, Thursz M, Dhar A, Lewis H, Vergis N, Lemoine M. Effect of COVID-19 Lockdown on alcohol consumption in patients with pre-existing alcohol use disorder. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5:886-887. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 10. | The Lancet Gastroenterology Hepatology. Drinking alone: COVID-19, lockdown, and alcohol-related harm. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5:625. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Alcohol Change UK. Lockdown Easing Press Release: New Research Indicates That Without Action Lockdown Drinking Habits May Be Here To Stay. 2020. [Cited 14 September 2021]. Available from: https://alcoholchange.org.uk/. |

| 12. | Pollard MS, Tucker JS, Green HD Jr. Changes in Adult Alcohol Use and Consequences During the COVID-19 Pandemic in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2022942. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 431] [Cited by in RCA: 581] [Article Influence: 116.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Finlay I, Gilmore I. Covid-19 and alcohol-a dangerous cocktail. BMJ. 2020;369:m1987. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 17.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | HMRC. Alcohol bulletin commentary (May 2021 to July 2021). 2021. [cited 14 September 2020]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/alcohol-bulletin/alcohol-bulletin-commentary-february-2021-to-april-2021. |