Published online Aug 16, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i23.8417

Peer-review started: April 18, 2022

First decision: May 12, 2022

Revised: May 25, 2022

Accepted: July 5, 2022

Article in press: July 5, 2022

Published online: August 16, 2022

Processing time: 104 Days and 21.9 Hours

Tracheal tumors may cause airway obstruction and pose a significant risk to ventilation and oxygenation. Due to its rarity, there is currently no established protocol or guideline for anesthetic management of resection of upper tracheal tumors, therefore individualized strategies are necessary. There are limited number of reports regarding the anesthesthetic management of upper tracheal resection and reconstruction (TRR) in the literature. We successfully used intravenous ketamine to manage a patient with a near-occlusion upper tracheal tumor undergoing TRR.

A 25-year-old female reported progressive dyspnea and hemoptysis. Bron

Ketamine showed great advantages in the anesthesia of upper TRR by providing analgesia with minimal respiratory depression or airway collapse.

Core Tip: The anesthetic management of upper tracheal resection and reconstruction (TRR) is challenging, since the tracheal tumor poses a significant risk to the patient’s ventilation and oxygenation. In a patient with a near-occlusion upper tracheal tumor, we successfully maintained spontaneous breathing during tracheostomy in TRR with anesthesia provided by intravenous ketamine and local anesthetic infiltration. Ketamine shows great advantages in providing adequate analgesia and cough suppressant effects with minimal respiratory depression. We hope our experience adds to the knowledge of airway management of upper TRR.

- Citation: Xu XH, Gao H, Chen XM, Ma HB, Huang YG. Using ketamine in a patient with a near-occlusion tracheal tumor undergoing tracheal resection and reconstruction: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(23): 8417-8421

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i23/8417.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i23.8417

The tracheal tumor causes airway obstruction and poses a significant risk to the patient’s ventilation and oxygenation. The incidence of primary tracheal tumors is as low as 2.6 cases per 1000000 people per year[1]. Due to its rarity, there is currently no established protocol or guideline for anesthetic management of resection of upper tracheal tumors, therefore individualized strategies are necessary. There are limited number of reports regarding anesthesia management of upper tracheal resection and reconstruction (TRR) in the literature. Laryngeal mask airway (LMA), high-frequency jet ventilation (HFJV), and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) have been successfully used for maintaining oxygenation during TRR[2-7].

We reported a case of a patient with a near-occlusion upper tracheal tumor undergoing TRR. In this case, we maintained spontaneous breathing during tracheostomy, and used intravenous ketamine to provide adequate analgesia and sedation.

A 25-year-old female with a body mass index of 22.03 kg/m2 reported a 1-mo history of progressive dyspnea and hemoptysis.

Dyspnea was aggravated in the supine position and relieved in the right lateral position.

The airway evaluation showed normal mouth opening, Mallampati class II, mandibular protrusion, thyromental distance, and neck extension.

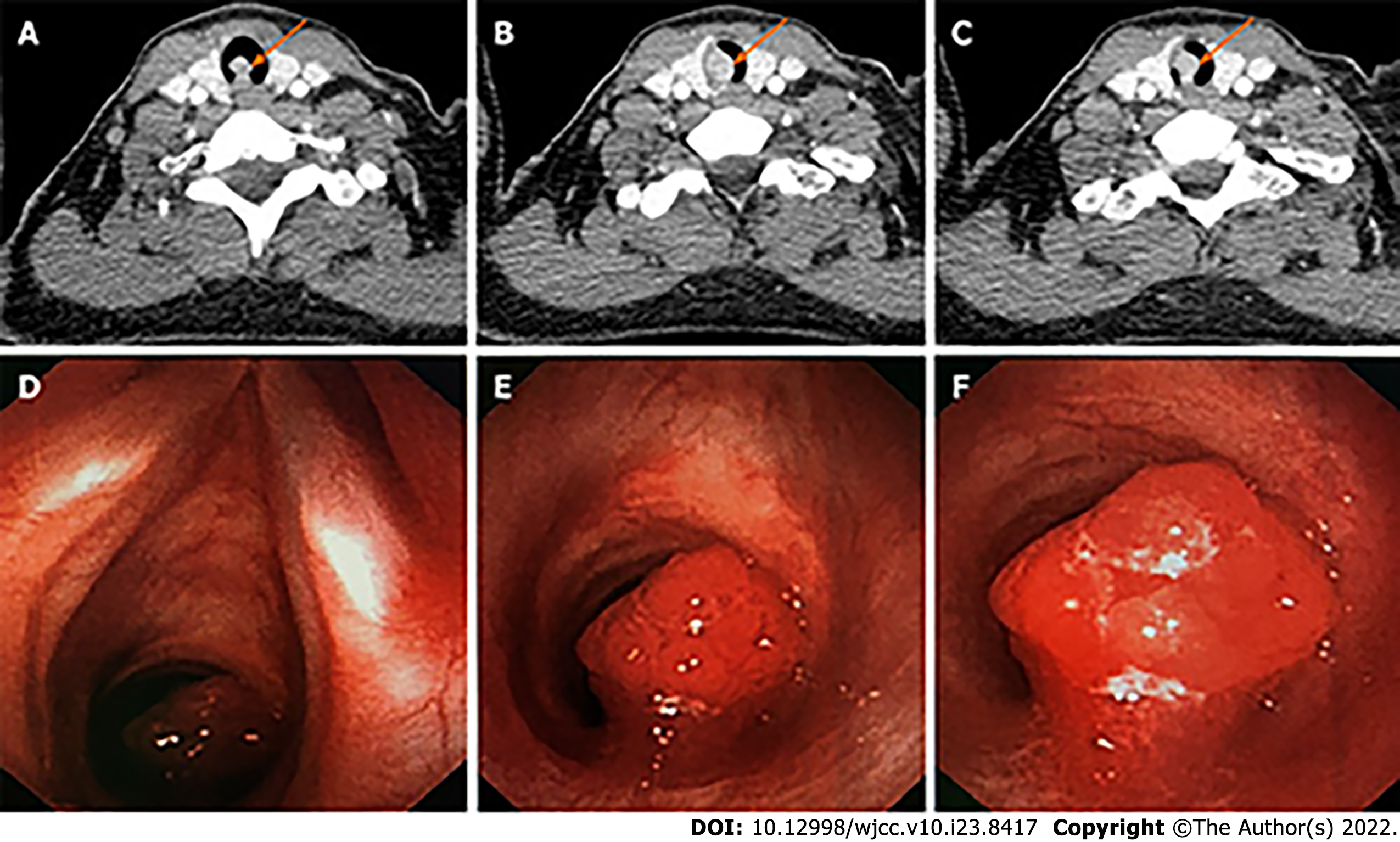

A neck computed tomography (CT) scan showed an 8.4 mm × 11.2 mm contrast-enhanced mass with soft-tissue density protruding from the right posterior wall into the tracheal lumen (Figure 1A-C). Bronchoscopy showed an intratracheal tumor located one tracheal ring below the glottis, which occluded more than 90% of the tracheal lumen (Figure 1D-F). The tumor easily bled when being touched.

The pathologic finding was mucoepidermoid carcinoma.

The patient was scheduled for TRR through a lower collar incision. The size and level of the patient’s tracheal tumor precluded orotracheal intubation. To secure the patient’s airway, we needed to maintain spontaneous breathing, provide pain control, and avoid coughing. To achieve these goals, we decided to secure the airway through tracheostomy with analgesia and sedation provided by intravenous ketamine and local anesthetic infiltration, followed by general anesthesia.

The patient entered the operating room with a pulse oxygen saturation of 100%. We provided continuous oxygen delivery through a nasal cannula at 2 L/min. The patient was positioned at a slight left lateral position where she could breathe most comfortably. The anesthesia was induced with 1 mg/kg ketamine. The sedation was then titrated with spontaneous breathing reserved. We gave 20 mg scopolamine intravenously to counteract the sialagogue effect from ketamine. Before skin incision, additional 0.5 mg/kg ketamine and 0.5 μg/kg fentanyl were administered intravenously to enhance analgesia, and the surgeons injected 1% lidocaine 10 mL subcutaneously around the incision. The tracheostomy took about 25 min with minimal blood loss. The entry site for tracheotomy was between the 4th and 5th cartilage rings, and a sterile endotracheal tube (ETT, internal diameter 6.5 mm) was placed into the distal trachea. The ETT was connected to a sterile breathing circuit, which was passed through the surgical field and connected to the anesthesia machine. The ventilation was confirmed by a normal end-tidal carbon dioxide waveform. The general anesthesia was induced with 2 mg/kg propofol, 0.8 mg/kg rocuronium, and 1.5 μg/kg fentanyl, and maintained with continuous infusions of propofol, remifentanil, and lidocaine. The surgeons resected 1st to 4th cartilage rings with the tumor attached, anastomosed the posterior tracheal wall. We performed a video-laryngoscopy to place a new ETT. After the new ETT passed vocal cords, the surgeon removed the original ETT and guided the cuff balloon across the anastomotic line. Next, the surgical team anastomosed the anterior tracheal walls and closed the surgical incision. The overall surgery took a total of 75 min. At the end of the surgery, we suctioned the oropharynx thoroughly, administrated 10 mg dexamethasone to prevent postoperative anastomosis edema, and stopped propofol and remifentanil infusion. Neuromuscular blockade was reversed by 2 mg neostigmine and 1 mg atropine. After the spontaneous breathing was established, we extubated the patient uneventfully.

The patient received adjuvant radiotherapy after the surgery. There was no sign of relapse during the postoperative two-year follow-up.

The upper TRR presents challenges in airway and anesthetic management. In our case, the patient had a near-occlusion tracheal tumor, maintaining spontaneous breathing is of utmost importance. Local anesthetic infiltration for a tracheostomy to secure the airway at the first step is the safest approach. In this case, the surgeons used the subcutaneous injection of lidocaine before skin incision. The instillation of lidocaine directly on the trachea can also be considered after incision. However, the local anesthesia may not be adequate in this case due to the duration of the tracheostomy. The surgeons needed to accurately transect the trachea 1-2 cartilage rings below and above the tumor borders: a time-consuming process. Coughing and movement needed to be minimized. Ketamine provides analgesia and cough suppressant effects with minimal respiratory depression[8], and is superior to dexmedetomidine and propofol in minimizing upper airway collapse and maintaining compensatory responses to hypoxemia[9]. Adding intravenous ketamine to local anesthetic infiltration would provide better sedation and analgesia. Preoperative scopolamine or glycopyrrolate could counteract the sialagogue side effect from ketamine. Even though it did not happen in our case, hallucination from ketamine requires attention. Benzodiazepine or dexmedetomidine is helpful to control ketamine-induced hallucination[10].

There are several other options with their pros and cons in managing upper TRR. Bilateral cervical plexus block has been reported to maintain spontaneous breathing during TRR[5,6]. Nevertheless, a superficial plexus block would not be adequate, while a deep plexus block may block phrenic nerves and aggravate dyspnea, especially in the setting of a near-occlusion tracheal tumor. General anesthesia with LMA has been successfully used for tumors that occluded 65%-90% of the tracheal lumen[3,4]. However, there is a risk of complete airway collapse and obstruction after induction, especially in the high level of obstruction. If the tracheal tumor is small, a small endotracheal tube or HFJV cannula may be used to maintain ventilation[6,7]. Hemorrhage or tumor spreading would be a concern if the tumor is vascular or malignant in nature. For patients with a large tumor and respiratory distress, the ultimate backup plan is ECMO.

After TRR, the patient needs to maintain a neck-flexion position to minimize anastomosis tension. Agitation, coughing, laryngospasm, or vomiting may increase anastomosis tension. Anesthesia should be lightened cautiously during emergence. If reintubation is needed, a fiberoptic assisted approach is preferred.

In conclusion, we successfully maintained spontaneous breathing during tracheostomy in TRR with anesthesia provided by intravenous ketamine and local anesthetic infiltration. Ketamine shows great advantages in the airway management in patients with near-occlusion tracheal tumors, since it provides adequate analgesia with minimal respiratory depression. The efficacy and safety of ketamine can be evaluated by in-depth comparative studies in the future.

We would thank Dr. Philip Chan from Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School for helping revise the manuscript.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Anesthesiology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Cordunianu AGV, Romania; Ferreira GSA, Brazil S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: A P-Editor: Yan JP

| 1. | Urdaneta AI, Yu JB, Wilson LD. Population based cancer registry analysis of primary tracheal carcinoma. Am J Clin Oncol. 2011;34:32-37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Andolfi M, Vaccarili M, Crisci R, Puma F. Management of tracheal chondrosarcoma almost completely obstructing the airway: a case report. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2016;11:101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Wendi C, Zongming J, Zhonghua C. Anesthesia airway management in a patient with upper tracheal tumor. J Clin Anesth. 2016;32:134-136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Schieren M, Egyed E, Hartmann B, Aleksanyan A, Stoelben E, Wappler F, Defosse JM. Airway Management by Laryngeal Mask Airways for Cervical Tracheal Resection and Reconstruction: A Single-Center Retrospective Analysis. Anesth Analg. 2018;126:1257-1261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Liu J, Li S, Shen J, Dong Q, Liang L, Pan H, He J. Non-intubated resection and reconstruction of trachea for the treatment of a mass in the upper trachea. J Thorac Dis. 2016;8:594-599. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Zhou Y, Liu H, Wu X, Li S, Liang L, Dong Q. Spontaneous breathing anesthesia for cervical tracheal resection and reconstruction. J Thorac Dis. 2019;11:5336-5342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Pang L, Feng YH, Ma HC, Dong S. Fiberoptic bronchoscopy-assisted endotracheal intubation in a patient with a large tracheal tumor. Int Surg. 2015;100:589-592. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Chungsamarnyart Y, Pairart J, Munjupong S. Comparison of the effects of intravenous propofol and propofol with low-dose ketamine on preventing postextubation cough and laryngospasm among patients awakening from general anaesthesia: A prospective randomised clinical trial. J Perioper Pract. 2022;32:53-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Mishima G, Sanuki T, Sato S, Kobayashi M, Kurata S, Ayuse T. Upper-airway collapsibility and compensatory responses under moderate sedation with ketamine, dexmedetomidine, and propofol in healthy volunteers. Physiol Rep. 2020;8:e14439. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Trivedi S, Kumar R, Tripathi AK, Mehta RK. A Comparative Study of Dexmedetomidine and Midazolam in Reducing Delirium Caused by Ketamine. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10:UC01-UC04. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |