Published online Aug 16, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i23.8312

Peer-review started: February 21, 2022

First decision: May 30, 2022

Revised: June 13, 2022

Accepted: July 8, 2022

Article in press: July 8, 2022

Published online: August 16, 2022

Processing time: 160 Days and 21.6 Hours

Myeloid sarcoma (MS), including isolated and leukaemic MS, is an extram

We report a rare case of MS with involvement of the vulva and vagina and massive infiltration of the pelvic floor. A 26-year-old woman presented with a vulvar mass, irregular vaginal bleeding and night sweats. Magnetic resonance imaging demonstrated an ill-defined, irregular vulvovaginal mass with massive involvement of the paravaginal tissue, urethra, posterior wall of the bladder, and pelvic floor. The signal and enhancement of the huge mass was homogeneous without haemorrhage or necrosis. Positron emission tomography/computed tomography showed high fluorodeoxyglucose uptake by the mass. Peripheral blood count detected blast cells. Vulvovaginal mass and bone marrow biopsies were performed, and immunohistochemistry confirmed the diagnosis of acute myeloid leukaemia (M-2 type, FAB classification) and vulvovaginal MS. The patient was treated with induction chemotherapy followed by allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation, and achieved complete remission. A systemic review of the literature on vulvovaginal MS was conducted to explore this rare entity’s clinical and radiological features.

Vulvovaginal MS is extremely rare. Diagnosis of vulvovaginal MS can only be confirmed histo

Core Tip: Female genital tract involvement in myeloid sarcoma (MS) is rare, and involvement of the vagina and vulva is extremely rare. Vulvovaginal MS can be localised or invade the adjacent cervix or paravaginal tissue. We report a rare case of MS with involvement of the vulva and vagina as well as massive infiltration of the pelvic floor. The clinical, pathological and imaging characteristics and treatment are reviewed to probe this rare entity.

- Citation: Wang JX, Zhang H, Ning G, Bao L. Vulvovaginal myeloid sarcoma with massive pelvic floor infiltration: A case report and review of literature. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(23): 8312-8322

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i23/8312.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i23.8312

Myeloid sarcoma (MS) is defined as an extramedullary myeloid tumour composed of immature myeloid cells[1], including isolated MS and leukaemic MS. Leukaemic MS is a rare manifestation of leukaemia and has been reported in 2.5%–9.1% of acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) patients, and is five times less frequent in patients with chronic myelogenous leukaemia[2]. It can occur with or after the onset of AML, acute lymphocytic leukaemia, myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) or chronic myeloproliferative disorder. Isolated MS, however, is not accompanied by the above haematological diseases and thus can be difficult to diagnose by clinical, radiological, or even pathological methods. It is a rare disease with an incidence of 2/1000000 in adults[3]. Considering that the detection of MS can be an indication of poor prognosis regardless of the clinical setting[4], timely diagnosis is of importance. Even though the diagnosis of MS can only be confirmed histopathologically, imaging examination plays an important role in both diagnosis and treatment guidance. MS can involve any anatomical site, either concurrently or sequentially, with skin, lymph nodes, gastrointestinal tract and soft tissue being the most common[5]. Other reported sites include the central nervous system and the genitourinary system. Female genital tract involvement in MS is rare, and the most commonly involved organ is the ovaries, followed by the uterus. Involvement of the vagina and vulva is extremely rare. Vulvovaginal MS can be localised or invade the adjacent cervix or paravaginal tissue[6-17].

Vulvar mass, irregular vaginal bleeding and night sweats for 1 mo.

A 26-year-old nulliparous woman came to our gynaecological department, complaining of a vulvar mass, irregular vaginal bleeding and night sweats for 1 mo.

The patient had no past illness.

The patient had no personal or family history.

Pelvic examination found that her left vulva, vagina and cervix were swollen. The bimanual examination revealed a vulvovaginal mass fixed to the pelvic wall.

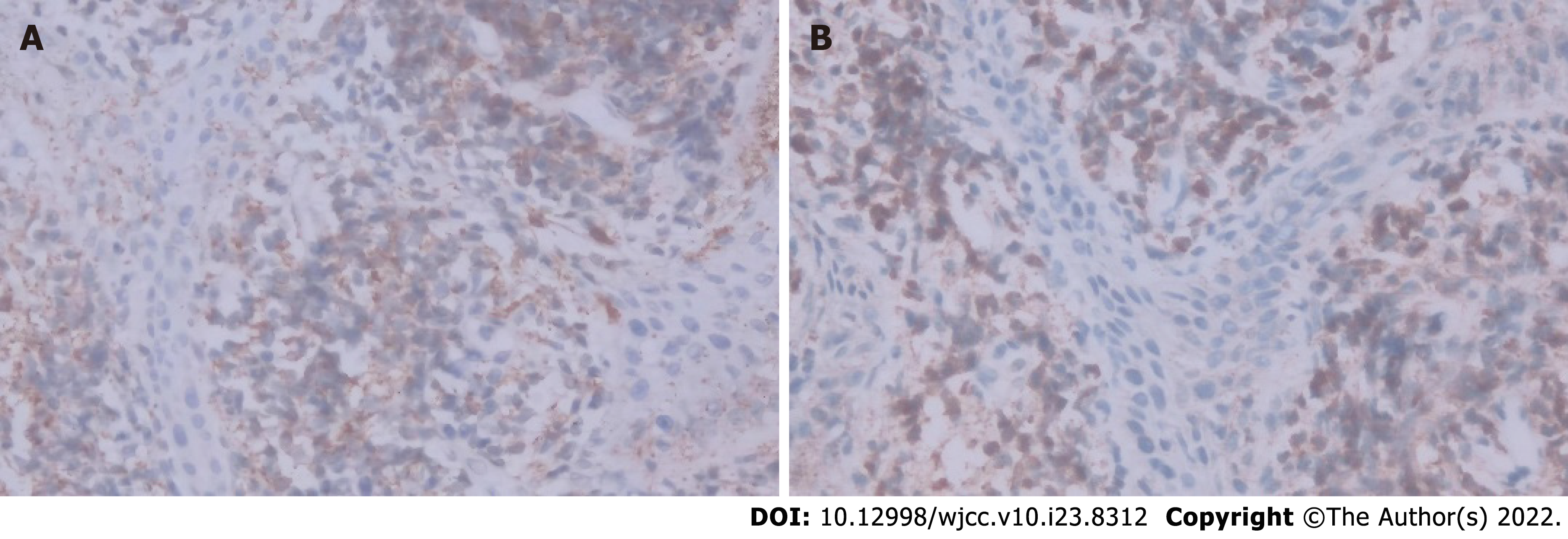

Serum tumour markers, including a-fetoprotein, carcinoembryonic antigen, carbohydrate antigen (CA) 125, CA19-9 and human chorionic gonadotropin were all within the normal range. Immediately after her admission, the peripheral blood count showed that the white blood cell count was 3.7 × 109/L, haemoglobin and platelets were normal, and blasts were detected. A vulvovaginal mass biopsy was performed, and the initial result was a malignant small round cell tumour. Two weeks later, the patient had the peripheral blood count retested, and the white blood cell count was 18.9 × 109/L, haemoglobin 102 g/L, and platelets 24 × 109/L. Her peripheral blood smear revealed 79.0% blast cells. Immunohistochemical staining of bone marrow demonstrated positive reactions with myeloperoxidase (MPO) blast cells and the others were all negative. A bone marrow biopsy was performed, and a bone marrow smear showed that the proportion of myeloblasts was 64.5%, and that of erythroid cells was only 6.5%. Mature lymphocyte accounted for 11%, and only two megakaryocytes and a few platelets were seen. Flow cytometric studies in bone marrow showed that myeloblasts accounted for 76.0% of the nucleated cells, which expressed HLA-DR, CD117, CD13, CD33 and cMPO, and were weakly positive for CD34, CD123, CD38 and CD64, while negative for CD14, CD36, cCD3, CD5, CD7, CD56 and CD19. Fluorescence in situ hybridisation detected mutation in ETV6 and NPM1. Further immunohistochemistry of the vaginal mass biopsy was positive for CD99 and MPO (Figure 1).

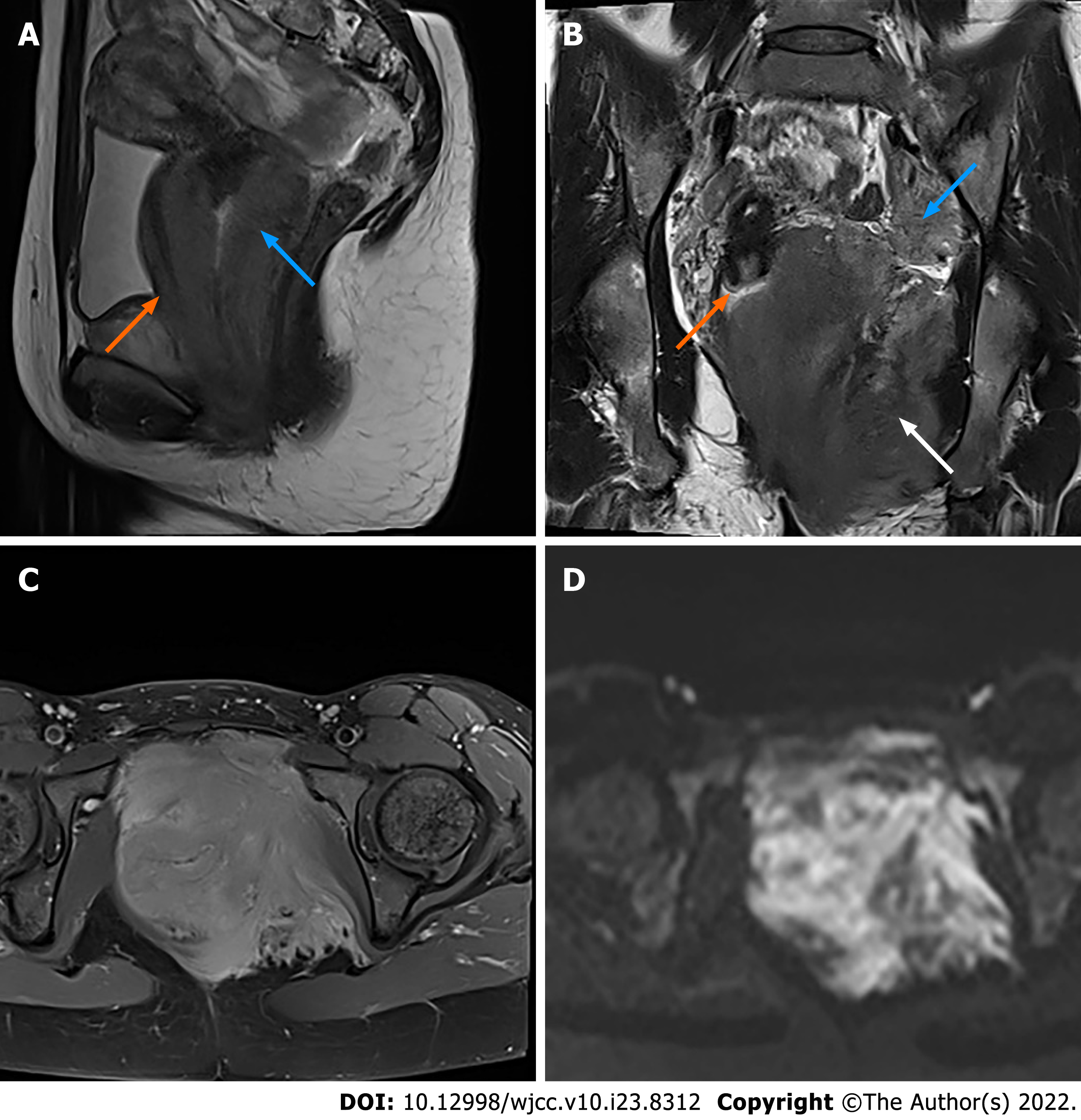

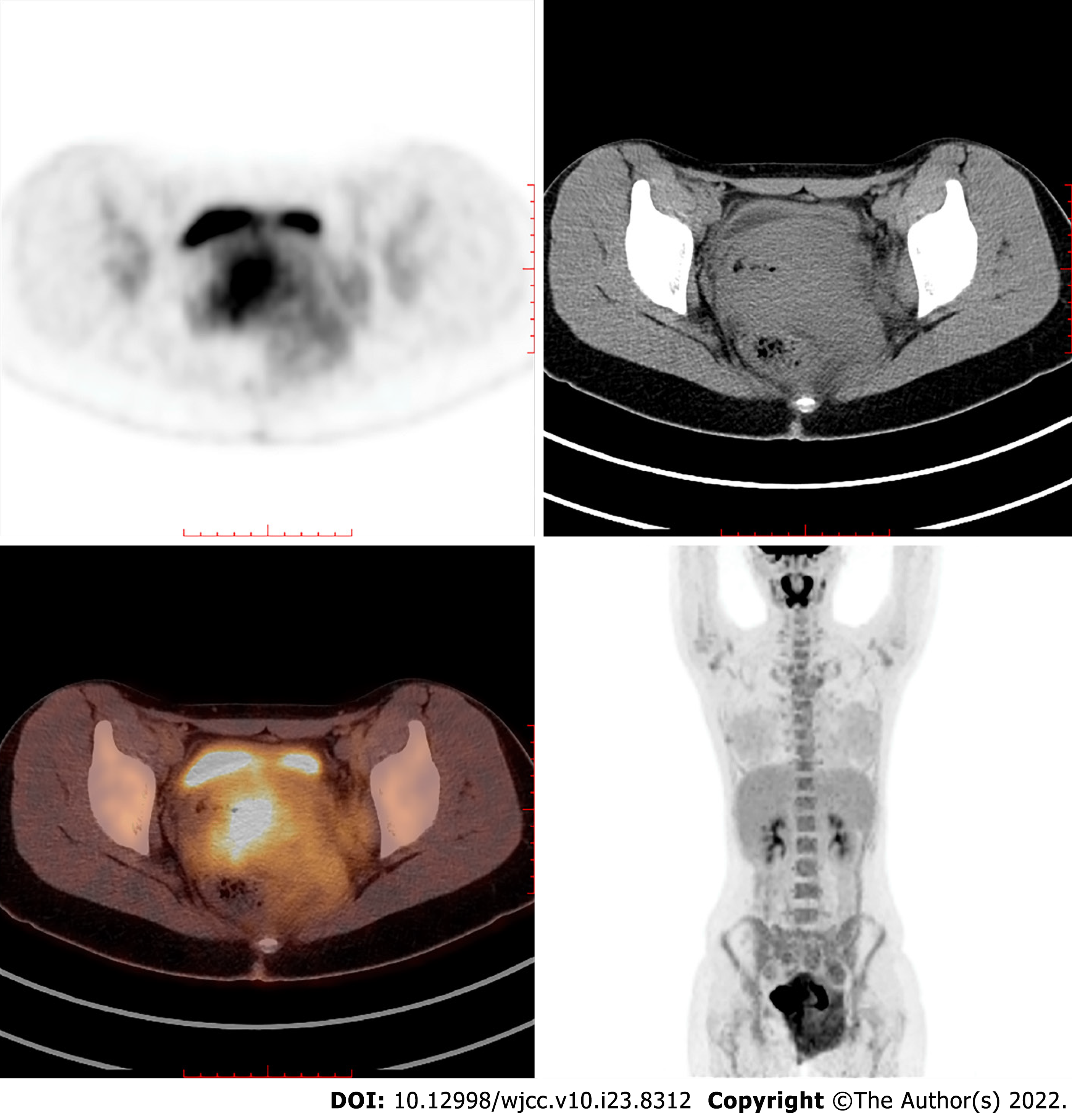

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with contrast enhancement of the pelvis demonstrated an ill-defined, irregular, diffuse mass with involvement of the vagina, paravaginal tissue, urethra, posterior wall of the bladder, left ischiorectal fossa, left side of the pelvic diaphragm and pelvic floor, with a maximum diameter of 10.5 cm × 9.0 cm in the axial plane. The lesion was homogeneously isointense on T1-weighted imaging (T1WI), slightly hyperintense on T2-weighted imaging (T2WI) and diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) (b = 800), and hypointense on apparent diffusion coefficient images with homogeneous enhancement greater than the muscle (Figure 2). Bilateral obturator lymph nodes were enlarged, especially on the left side. The signal and enhancement of the uterus, cervix and bilateral ovaries were normal. Positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) showed high fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake in the mass and bilateral obturator lymph nodes, indicating malignancy (Figure 3). Thoracic CT was performed with no positive findings.

Bone marrow aspirate, cytochemistry and flow cytometry confirmed the diagnosis of AML (M-2 type, FAB classification). Further immunohistochemistry of the vaginal mass biopsy confirmed the presence of vulvovaginal MS.

Upon the confirmed diagnosis, the patient received two cycles of induction chemotherapy (idarubicin, 20 mg d 1–3 + cytarabine 170 mg d 1–7). During the first course of chemotherapy, the patient developed fever and bacterial pneumonia, and responded well to antibiotics. Complete haematological remission was obtained and no vulvovaginal mass was found by pelvic examination after the second course of induction chemotherapy. Cytarabine (5 g q12h on d 1, 3 and 5) was administered as consolidation chemotherapy. The patient then received azacitidine, fludarabine, busulfex, Ara-C and antithymocyte globulin as the conditioning regimen, which was well tolerated. The graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis consisted of cyclosporine, mycophenolate mofetil and short-range methotrexate. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) was performed using peripheral blood stem cells from her haploidentical father (6/12). The neutrophil and platelet engraftment achieved +10 d. Bone marrow smear showed that the proportion of myeloblasts was 2.5% and the ratios of granulocytes to erythrocytes was reduced. Flow cytometry of the bone marrow showed no malignant blasts. The patient achieved complete donor chimerism. PET/CT showed negative FDG uptake in the pelvic cavity, pelvic floor, retroperitoneum and red bone marrow. Twelve courses of pelvic radiotherapy were administered.

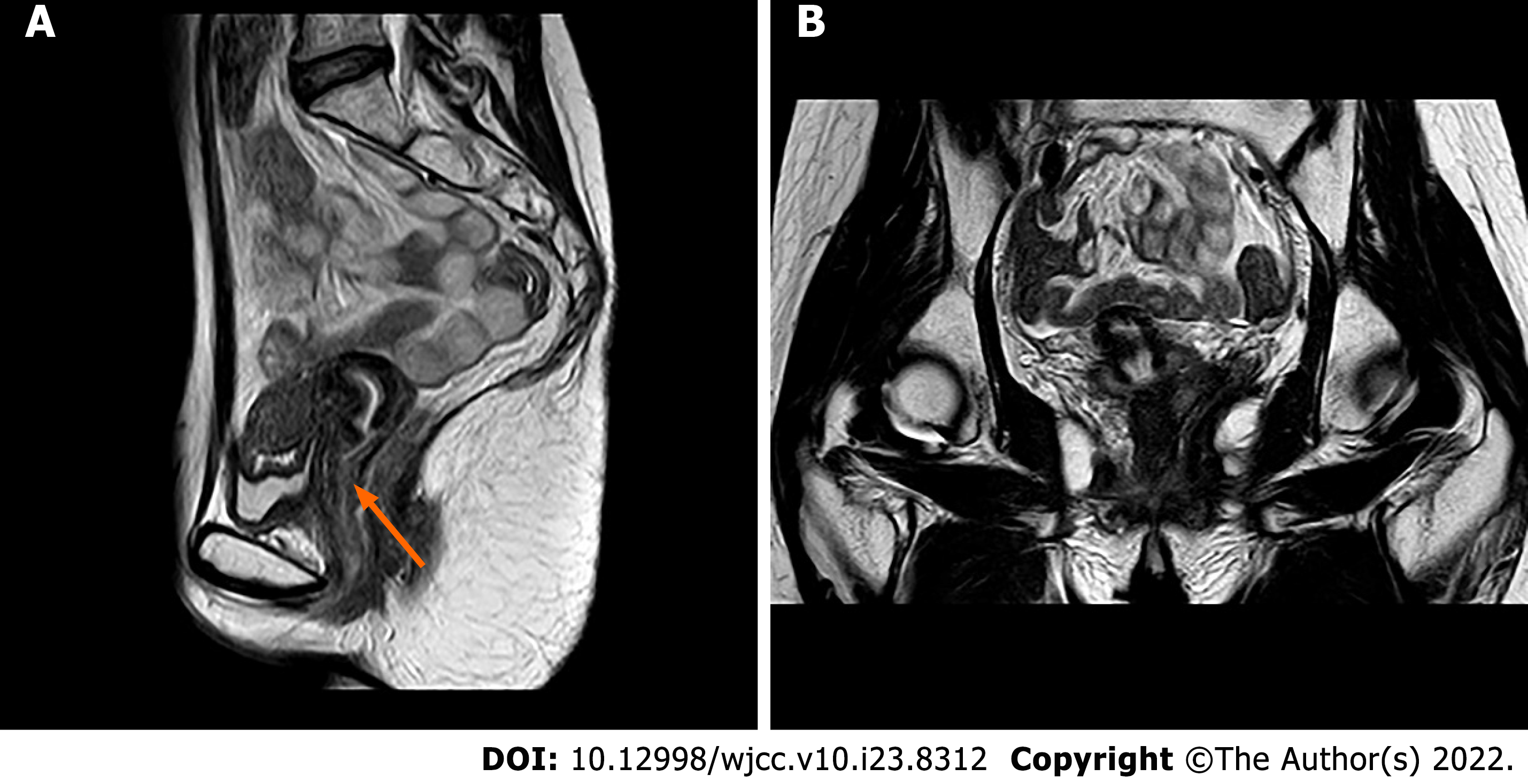

Until now, the patient has been in complete remission for 2 years after hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation (HSCT). Recent pelvic MRI showed no sign of tumour recurrence (Figure 4).

The present case was leukaemic MS involving the vulva and vagina, with massive infiltration of the pelvic floor. We searched the literature on MS in the vagina and/or vulva to explore this rare entity’s clinical and radiological features. There were 16 reported cases of MS involving the vagina and/or the vulva, of which, 11 reported the radiological findings, including our case (Table 1). Among the 16 cases, eight were isolated MS, and eight were leukaemic MS, which included five cases of M2, two of M5, and one case of leukaemia with no specific subtype mentioned. MS can occur at any age; however, children are generally more often affected than adults, with 60% of patients younger than 15 years[18]. Patients with vulvovaginal MS were older; in the 16 case reports, they were aged from 16 to 77 years, with a median age of 44 years. Patients with MS can be asymptomatic, or with various clinical manifestations that are mainly determined by specific location and size[19]. Typical initial symptoms of vulvovaginal MS are vaginal/vulvar mass or vaginal bleeding. Other presentations include genitourinary tract infection and local swelling. Histologically, MS is frequently undifferentiated and consequently is often misdiagnosed, particularly in patients whose tumours precede the appearance of overt leukaemia symptoms or when the neoplasm is found at an unusual location[20]. Malignant small cell tumours can occasionally be difficult to distinguish from granulocytic sarcoma, especially when only small biopsy samples are available for examination[21], as in our case. In addition, most isolated MS is poorly differentiated, and the correct diagnosis is made or suspected by routinely stained sections in only 44% of cases[9]. Therefore, once the possibility of MS is considered, cytochemical and immunohistochemical studies can reliably make the distinction in nearly all cases[22]. Immunohistochemistry is essential for the diagnosis and differential diagnosis of MS. The most commonly used immunohistochemical antibody markers are MPO, lysozyme, CD68 and CD99. The presence of eosinophilic myelocytes or granulocytic differentiation in neoplastic cells suggests a diagnosis of MS. Myeloid cells and blast cell markers CD117, CD34 and CD43, are positive in the immunophenotype, which is helpful for diagnosis. MPO, a specific marker for granulocytic sarcoma, is the most commonly used antibody for diagnosing MS with high specificity and sensitivity. However, MPO is often not expressed in less-differentiated MS. Lysozyme is the most sensitive marker of myeloid cells and is expressed in granulocytes and monocyte lines, especially in differentiated immature myeloid cells, and the positive rate reaches 60%–90%. However, lysozyme is contained in many tissues in the human body, so its specificity is lower than that of MPO. In the reported cases, nine (56%) were CD68 positive, eight (50%) were CD117, and MPO positive, and the positive rates of lysozyme, CD43 and CD34 were 38% (6 cases), 31% (5 cases) and 25% (4 cases), respectively. Therefore, the combination of multiple relevant immunohistochemical antibody markers may help with the final diagnosis.

| Ref. | Age (yr) | Symptom | Past history | Immunophenotype (+) | Location | Maximum diameter (cm) | Imaging examination | Lymphadenopathy | Type (FAB classification) | Treatment | Follow-up |

| Kamble et al[15], 1997 | 33 | Hypermenorrhea, pain and fever | NS | NS | The vagina fornix and the cervix | 7.0 | US: A hypoechoic mass extending posteriorly to the vagina and bilateral dilated lower end of ureter. | NS | M2 | Symptomatic treatment | Died (renal failure and fungaemia) |

| Unterweger et al[12], 2002 | 30 | Vaginal bleeding, vaginal mass and fatigue | NS | MPO, lysozyme, CEA | The vaginal fornix and the cervix | 5.0 | MRI: A large tumor on the anterior vaginal wall extending to the cervix, suspected infiltration of the urinary bladder; CT: A homogeneous tumor appears in the the vagina, cannot be separated from the cervix; US: A homogeneous, predominantly solid space requirement of the anterior vaginal wall | The mediastinal LN | M5 | Chemo | CR |

| Imagawa et al[6], 2010 | 25 | Stinking vaginal discharge | NS | Lysozyme, CD68, CD34 | The rectovaginal septum and the vaginal cavity | 7.9 | MRI: A large solitary tumor located in the vagina; PET/CT: The vaginal tumor demonstrated an increased FDG uptake with a SUV of 7.6 | NS | M2 | Chemo | CR, 3 y |

| Skeete et al[7],2010 | 77 | Vaginal mass, urinary incontinence and fatigue | No | MPO, CD68, CD43, CD45 | The vaginal wall | NS | CT: A mass involving the vagina extending to the cervix with thickening of the vaginal wall | No | Isolated MS | Chemo, RT | Died (condition deteriorated and dyspnea) |

| Qiang et al[14], 2010 | 52 | Vaginal mass | Isolated MS in the cervix reached CR with chemo and hysterectomy 11 yr ago | MPO, CD117 | The vaginal stump | 8.0 | MRI: A pear-shaped homogeneous mass arising from the vaginal stump | NS | Isolated MS | Chemo | Died (sepsis) |

| Nazer et al[8], 2012 | 41 | Vaginal mass | AML (M5) reached CR 10 mo ago | MPO, CD117, CD43 | The vulva, the vaginal and adjacent cervix | NS | MRI: Intermediate signal intensity mass surrounding the vagina, cervix and urethra with intact fibrous stromal tissue, invading the parametrium with involvement of the labia minora. | NS | Isolated MS | Chemo, RT | CR, 8 mo (multiple site relapse) |

| Modi et al[9], 2015 | 68 | Vaginal bleeding | No | MPO, CD117, LCA | The vaginal fornix and vaginal wall | 6.0 | CT: Well-defined homogenously enhancing lesion arising from the left side of the vagina, projecting into vaginal lumen | NS | Isolated MS | Chemo | Asymptomatic |

| Yuan et al[11], 2015 | 40 | Vaginal bleeding and vaginal mass | No | MPO, CD68, CD117, CD34, LCA, CD38, CD79a | The vulva, the vagina and the cervix | 9.0 | PET-CT: A soft tissue mass in the vulva, vagina, and cervix, with irregular shape, unclear border, and with a SUV of 2.4 | The left inguinal region LN | Isolated MS | Chemo (only one cycle) | Died |

| Madabhavi et al[10], 2016 | 38 | Vaginal bleeding | No | MPO, CD117, LCA | The vaginal fornix | 5.0 | CT: A mass lesion located in the vagina, mild hepatomegaly, and splenomegaly | The supra and infra diaphragmatic LN | Isolated MS | Chemo, RT | Asymptomatic |

| Hu et al[13], 2016 | 45 | Vaginal mass and anuria | HSCT for MDS 7 yr ago | Lysozyme, CD117, CD34, CD56 | The vulva, bilateral adnexae and bilateral perirenal spaces | 2.5 | US: bilateral hydronephrosis with a nondistended bladder; CT/MRI: multiple tumours in the bilateral perirenal spaces and bilateral adnexae with encasement of bilateral ureters | NS | M5 | Chemo | Died |

| Present case | 26 | Vaginal bleeding and vaginal mass | No | CD99, CD68, CD15, LAC | The vulva, the vagina and massive infiltration of the pelvic floor | 10.5 | MRI: Ill-defined, irregular, diffuse mass with involvement of the vagina, paravaginal tissue, the urethra, posterior wall of the bladder, the left ischiorectal fossa, the left side of the pelvic diaphragm and the pelvic floor | The bilateral obturator LN | M2 | Chemo, HSCT | CR |

| Erşahin et al[17], 2007 | 73 | Vulval swelling and stinking vaginal discharge | Breast lesion since 3-6 yr ago | CD9, CD13, CD15, CD33, HLA-DR | The vulva | 6.0 | NS | NS | M2 | Chemo | Died (breast cancer with multiple metastases) |

| Skeete et al[7], 2010 | 36 | Vaginal mass | AML recurred repeatedly since 8 yr ago | CD68 | The vagina and the rectovaginal septum | A large mass | NS | No | AML without subtype | Chemo, RT | Died (leukemic relapse) |

| Policarpio-Nicolas et al[16], 2012 | 16 | Vaginal mass | No | Lysozyme, CD117, CD68, CD43, CD34, CD45RB, CD56, tdt | The vulva | 2.0 | NS | The left inguinal LN | Isolated MS | Chemo | CR, 11 mo |

| Bao et al[5], 2019 | 53 | Vaginal bleeding and vaginal mass | Uterine fibroids | Lysozyme, CD68, CD43, CD45, CD4, CD163, CD56 | The vagina | 8.0 | NS | NS | Isolated MS | Hysterectomy and resection of vaginal mass, chemo, HSCT | CR |

| Zhang et al[1],2019 | 47 | Vaginal ulceration and fever | No | MPO, lysozyme, CD68, CD43, CD38, CD117, Ki-67 | The valva | NS | NS | NS | M2 | Chemo, HSCT | CR, 27 mo |

Imaging examination plays an important role in the diagnosis of MS. Different imaging tests can be performed according to the location of the tumour[23]. Ultrasonography (US) is convenient, efficient, and radiation free. It has certain advantages for superficial lesions, such as breast and skin MS; however, it is not sensitive in detecting vulvovaginal lesions, especially in paediatric patients when transvaginal US is avoided. CT can locate masses in different anatomical sites and demonstrate the tumour’s size, shape, local invasion, and lymph node metastasis. However, the soft-tissue contrast resolution of CT is not high, and the vulva and vagina cannot be clearly delineated. PET/CT can detect metabolically active tissue and are effective in the detection and localisation of various haematological malignancies[24], especially those with multiple lesions. However, false-negative results may still occur when FDG-PET alone is used to detect MS[25]. PET/CT is mainly suggested for planning radiotherapy and monitoring the treatment response[8]. Compared with other imaging examinations, MRI has irreplaceable advantages for diagnosing vulvovaginal lesions, with its excellent soft-tissue contrast, multiplanar capabilities and large field of view. MRI allows a detailed assessment of the anatomical extent of vulvovaginal MS and its characteristic appearance[26]. Among the 11 cases with imaging examinations, seven had MRI, five CT, three US, and two PET/CT. On imaging, vulvovaginal MS presented as a mass or nodule in the vaginal wall or vulva, ranging from 2.0 to 10.5 (mean 6.4) cm in the greatest dimension. The lesions were irregularly shaped with unclear borders. The vaginal wall was thickened, yet the vaginal mucosa was hardly affected. Half of them were located only at the vagina and/or the vulva, while the rest had invaded the adjacent tissues or organs, such as the cervix or the rectovaginal septum, indicating its invasiveness, which was consistent with a previous report[27]. Our case was the largest mass with extensive infiltration of the whole pelvic floor, which has not been found previously. On CT, the lesions were usually isodense, and on MRI, they were isointense on T1WI and slightly hyperintense on T2WI, with restricted diffusion on DWI. Due to the intrinsic high signal intensity of the tumour and the low signal intensity of the vaginal wall on T2WI, MRI can accurately demonstrate invasion into paravaginal tissues. The contrast enhancement patterns of MS were either homogeneous or peripheral enhancement. Calcification, haemorrhage or cystic degeneration were rare, therefore, the signal and enhancement of MS are usually homogeneous. Unilateral or bilateral lymph node metastasis was found in 5 cases, including local pelvic lymph nodes such as the obturator and inguinal lymph nodes, and distant metastasis such as in the mediastinal and phrenic lymph nodes. Even though leukaemic MS may have adjacent or systemic bone marrow abnormalities, which show decreased signal intensity on T1WI, increased signal intensity on fat-saturated T2WI or short time inversion recovery images, and diffuse gadolinium enhancement[28], these were not found or reported in the 11 cases. In general, the imaging features are nonspecific, and diagnosis of vulvovaginal MS without histopathological evidence is challenging or even impossible, especially for small lesions and isolated MS.

Even though the imaging findings of vulvovaginal MS are nonspecific, for our case, there were some useful clues before histopathological evidence. First, the patient was a young woman with massive infiltration of the pelvic floor, and this was different from vaginal squamous cell carcinoma, which most commonly occurs at an older age in the upper third of the vagina on the posterior wall. Primary vaginal adenocarcinoma occurs at a younger age, but it usually appears as a polypoid, papillary, plaque-like, or ulcerated lesion in the upper third and anterior wall of the vagina. Second, the signal of the lesion was homogeneous despite its massive size. Other huge vulvovaginal malignancies like sarcoma are usually heterogeneous due to haemorrhage or necrosis[29]. Moreover, the patient had night sweats and blasts were detected in her peripheral blood, indicating a possibility of haematological diseases. Pelvic lymphoma can be infiltrative with similar imaging presentations to MS. However, lymphoma may have extensive lymph node involvement. Treatment of vulvovaginal MS, as well as MS in all other sites, is similar to AML. Induction chemotherapy is now the standard of care, and additional radiotherapy is often considered when the disease persists after chemotherapy. Complete remission can be achieved with chemotherapy. In addition, allogeneic HSCT is a potentially efficient treatment for MS, with a substantial portion of patients achieving long-term remission and likely cure[30]. Surgery is not needed. Increasing age, comorbidities and complications are adverse prognostic factors of MS and usually predict treatment-related mortality[31]. This was also confirmed in our 16 cases of vulvovaginal MS. Seven patients achieved complete remission, with a median age of 34.0 years and no significant comorbidities or complications. Seven patients died with a median age of 50.9 years; among them, only one received one cycle of chemotherapy and rejected further treatment; two suffered MDS, breast cancer and Paget’s disease; and the other four either had leukaemia relapse or developed severe complications, such as renal failure, dyspnoea, fungemia and sepsis. The other two patients were asymptomatic after treatment, but additional details could not be obtained. It has been reported that earlier-stage MS patients achieve better outcomes, such as isolated MS[32]. However, this has not been confirmed in our cases. Our systematic review has a limitation. Information such as past history, immunophenotype, imaging examination and lymphadenopathy was not included in some cases.

Vulvovaginal MS is a rare disease that can be either isolated or leukaemic MS. It may present as localised or massive lesions with adjacent tissue infiltration. Even though the diagnosis of vulvovaginal MS is difficult without histopathological evidence due to its nonspecific clinical and imaging presentations, MS should be considered in the differential diagnosis of a newly developed T2-hyperintense homogeneously enhanced vulvovaginal mass, especially in a patient with suspected haematological malignancy.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Obstetrics and gynecology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Hegazy AA, Egypt; Kurniawati EM S-Editor: Xing YX L-Editor: A P-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Zhang X, Huang P, Chen Z, Bi X, Wang Y, Wu J. Vulvar myeloid sarcoma as the presenting symptom of acute myeloid leukemia: a case report and literature review of Chinese patients, 1999-2018. Diagn Pathol. 2019;14:126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lee JW, Kim YT, Min YH, Kim JW, Kim SH, Park KH, Lim BJ, Yang WI. Granulocytic sarcoma of the uterine cervix. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2004;14:553-557. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Neiman RS, Barcos M, Berard C, Bonner H, Mann R, Rydell RE, Bennett JM. Granulocytic sarcoma: a clinicopathologic study of 61 biopsied cases. Cancer. 1981;48:1426-1437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Shinagare AB, Krajewski KM, Hornick JL, Zukotynski K, Kurra V, Jagannathan JP, Ramaiya NH. MRI for evaluation of myeloid sarcoma in adults: a single-institution 10-year experience. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;199:1193-1198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Bao H, Gao J, Chen YH, Altman JK, Frankfurt O, Wilson AL, Sukhanova M, Chen Q, Lu X. Rare myeloid sarcoma with KMT2A (MLL)-ELL fusion presenting as a vaginal wall mass. Diagn Pathol. 2019;14:26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Imagawa J, Harada Y, Yoshida T, Sakai A, Sasaki N, Kimura A, Harada H. Giant granulocytic sarcoma of the vagina concurrent with acute myeloid leukemia with t(8;21)(q22;q22) translocation. Int J Hematol. 2010;92:553-555. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Skeete DH, Cesar-Rittenberg P, Jong R, Murray SK, Colgan TJ. Myeloid sarcoma of the vagina: a report of 2 cases. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2010;14:136-141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Nazer A, Al-Badawi I, Chebbo W, Chaudhri N, El-Gohary G. Myeloid sarcoma of the vulva post-bone marrow transplant presenting as isolated extramedullary relapse in a patient with acute myeloid leukemia. Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Ther. 2012;5:118-121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Modi G, Madabhavi I, Panchal H, Patel A, Anand A, Parikh S, Jain P, Revannasiddaiah S, Sarkar M. Primary vaginal myeloid sarcoma: a rare case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2015;2015:957490. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Madabhavi I, Patel A, Modi M, Revannasiddaiah S, Chavan C. Primary Vaginal Chloroma: A Rare Case Report. Int J Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Res. 2018;12:166-168. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Yu Y, Qin X, Yan S, Wang W, Sun Y, Zhang M. Non-leukemic myeloid sarcoma involving the vulva, vagina, and cervix: a case report and literature review. Onco Targets Ther. 2015;8:3707-3713. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Unterweger M, Caduff R, Ochsenbein-Imhof N, Kubik-Huch RA. [Vaginal granulocytic sarcoma: CT and MR imaging]. Praxis (Bern 1994). 2002;91:367-370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Hu SC, Chen WT, Chen GS. Myeloid sarcoma of the vulva as the initial presentation of acute myeloid leukaemia. Br J Dermatol. 2016;174:234-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Chiang YC, Chen CH. Cervical granulocytic sarcoma: report of one case and review of the literature. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2010;31:697-700. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Kamble R, Kochupillai V, Sharma A, Kumar L, Thulkar S, Sharma MC, Mittal S. Granulocytic sarcoma of uterine cervix as presentation of acute myeloid leukemia: a case report and review of literature. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 1997;23:261-266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Policarpio-Nicolas ML, Valente PT, Aune GJ, Higgins RA. Isolated vaginal myeloid sarcoma in a 16-year-old girl. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2012;16:374-379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Erşahin C, Omeroglu G, Potkul RK, Salhadar A. Myeloid sarcoma of the vulva as the presenting symptom in a patient with acute myeloid leukemia. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;106:259-261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Guermazi A, Feger C, Rousselot P, Merad M, Benchaib N, Bourrier P, Mariette X, Frija J, de Kerviler E. Granulocytic sarcoma (chloroma): imaging findings in adults and children. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;178:319-325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Bakst RL, Tallman MS, Douer D, Yahalom J. How I treat extramedullary acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2011;118:3785-3793. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 270] [Cited by in RCA: 336] [Article Influence: 24.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ding J, Li H, Qi YK, Wu J, Liu ZB, Huang BC, Chen WX. Ovarian granulocytic sarcoma as the primary manifestation of acute myelogenous leukemia. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:13552-13556. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Oliva E, Ferry JA, Young RH, Prat J, Srigley JR, Scully RE. Granulocytic sarcoma of the female genital tract: a clinicopathologic study of 11 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:1156-1165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Garcia MG, Deavers MT, Knoblock RJ, Chen W, Tsimberidou AM, Manning JT Jr, Medeiros LJ. Myeloid sarcoma involving the gynecologic tract: a report of 11 cases and review of the literature. Am J Clin Pathol. 2006;125:783-790. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Yilmaz AF, Saydam G, Sahin F, Baran Y. Granulocytic sarcoma: a systematic review. Am J Blood Res. 2013;3:265-270. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Stölzel F, Röllig C, Radke J, Mohr B, Platzbecker U, Bornhäuser M, Paulus T, Ehninger G, Zöphel K, Schaich M. ¹⁸F-FDG-PET/CT for detection of extramedullary acute myeloid leukemia. Haematologica. 2011;96:1552-1556. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Ueda K, Ichikawa M, Takahashi M, Momose T, Ohtomo K, Kurokawa M. FDG-PET is effective in the detection of granulocytic sarcoma in patients with myeloid malignancy. Leuk Res. 2010;34:1239-1241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Parikh JH, Barton DP, Ind TE, Sohaib SA. MR imaging features of vaginal malignancies. Radiographics. 2008;28:49-63; quiz 322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Ooi GC, Chim CS, Khong PL, Au WY, Lie AK, Tsang KW, Kwong YL. Radiologic manifestations of granulocytic sarcoma in adult leukemia. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;176:1427-1431. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Navarro SM, Matcuk GR, Patel DB, Skalski M, White EA, Tomasian A, Schein AJ. Musculoskeletal Imaging Findings of Hematologic Malignancies. Radiographics. 2017;37:881-900. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Griffin N, Grant LA, Sala E. Magnetic resonance imaging of vaginal and vulval pathology. Eur Radiol. 2008;18:1269-1280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Chevallier P, Mohty M, Lioure B, Michel G, Contentin N, Deconinck E, Bordigoni P, Vernant JP, Hunault M, Vigouroux S, Blaise D, Tabrizi R, Buzyn A, Socie G, Michallet M, Volteau C, Harousseau JL. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation for myeloid sarcoma: a retrospective study from the SFGM-TC. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4940-4943. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Döhner H, Estey EH, Amadori S, Appelbaum FR, Büchner T, Burnett AK, Dombret H, Fenaux P, Grimwade D, Larson RA, Lo-Coco F, Naoe T, Niederwieser D, Ossenkoppele GJ, Sanz MA, Sierra J, Tallman MS, Löwenberg B, Bloomfield CD; European LeukemiaNet. Diagnosis and management of acute myeloid leukemia in adults: recommendations from an international expert panel, on behalf of the European LeukemiaNet. Blood. 2010;115:453-474. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2353] [Cited by in RCA: 2566] [Article Influence: 171.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Tsimberidou AM, Kantarjian HM, Wen S, Keating MJ, O'Brien S, Brandt M, Pierce S, Freireich EJ, Medeiros LJ, Estey E. Myeloid sarcoma is associated with superior event-free survival and overall survival compared with acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer. 2008;113:1370-1378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |