Published online Aug 16, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i23.8224

Peer-review started: June 8, 2021

First decision: July 15, 2021

Revised: July 27, 2021

Accepted: July 8, 2022

Article in press: July 8, 2022

Published online: August 16, 2022

Processing time: 419 Days and 1.7 Hours

Gouty tophi are a chronic granulomatous caused by a deposition of monosodium urate crystal deposition in the body. Once broken, it may easily induce severe infection. Sepsis complicated with secondary hemophagocytic syndrome induced by gouty tophi rupture is extremely rare in the clinical setting, and no such serious complications have been reported in literature.

This is a 52-year-old Chinese male patient with a 20-year history of gouty arthritis. At admission, the gout stone in the patient’s right ankle was broken and it secreted a white mucoid substance. During the course of treatment, the patient suffered from systemic inflammatory response syndrome multiple times. His condition gradually deteriorated, further complicated by hemophagocytic syndrome. After thorough removal of gout lesions and active anti-infection treatment and control of blood uric acid level, combined with multidisciplinary cooperation, the patient was finally cured.

Sepsis complicated with secondary hemophagocytic syndrome induced by gouty tophi rupture is extremely rare in the clinical setting. Timely and accurate diagnosis is very important to save patients' lives.

Core Tip: Sepsis and secondary hemophagocytic syndrome induced by gouty tophi rupture are very rare in a clinical setting. Since the early symptoms are similar to gouty arthritis, it is easy to ignore septic infection and immune system damage. Sepsis and hemophagocytic syndrome develop rapidly. Often, when detected by clinicians, patients have life-threatening symptoms. This case emphasizes that clinicians should screen patients with gouty tophi rupture for early complications of sepsis and immune system damage. It is, therefore, important to improve the relevant examination as soon as possible and initiate early intervention.

- Citation: Lai B, Pang ZH. Sepsis complicated with secondary hemophagocytic syndrome induced by giant gouty tophi rupture: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(23): 8224-8231

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i23/8224.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i23.8224

Gouty tophi are a chronic granulomatous caused by the deposition of monosodium urate crystals in and around the joint[1]. The main clinical manifestations are joint fever, swelling, and severe pain. When the gouty tophi are large, they may be palpated as a subcutaneous induration. In severe cases, joint bone destruction occurs, leading to joint dysfunction or even disability[2,3]. There have been increased reports of unusual concomitant gout and infections, such as septic arthritis and necrotizing fasciitis, in some coastal areas[4,5]. Gouty and septic arthritis can cause joint fever, swelling, and local erythema, making them difficult to distinguish from each other based on clinical symptoms alone[6]. As such, bacterial culture and Gram staining are necessary to exclude septic arthritis[7]. Although this phenomenon is not common clinically, a 15-year case study has confirmed this[4]. The hemophagocytic syndrome (HPS) is a rare immune-activated disease characterized by excessive systemic inflammation. It can be divided into two types: familial and secondary[8]. Secondary HPS usually occurs in the setting of infection, malignant lesions, rheumatism, and metabolic diseases[8,9]. The main clinical symptoms include high fever, hepatosplenomegaly, and hemocytopenia, accompanied by pulmonary dysfunction and neurological symptoms (including epilepsy, meningitis, and decreased consciousness)[10]. It is not an independent disease, but a group of clinical syndromes involving multiple organs. HPS is associated with a variety of potential diseases and can occur as a genetic or acquired disease[10,11]. At present, HPS following immune system damage caused by gouty tophi is very rare and has not been reported in the relevant literature. Herein, we report a rare case caused by the rupture of huge gouty tophi, resulting in infection at the site of the rupture, rapid development of sepsis, and eventually, destruction of the immune system in the later stage of the disease, leading to secondary HPS.

A 52-year-old Chinese male patient complained of recurrent right ankle pain and swelling for 20 years. He presented to our out-patient department on August 8, 2019.

The pain in the right ankle was repeated and aggravated at night. The maximum visual analogue scale was 9 points.

The patient’s height was 169 cm and weight was 65 kg. He had a history of hyperuricemia and alcohol drinking for 20 years, but he did not take drugs regularly.

He had no trauma history, no other special diseases, or family genetic history.

His right ankle joint was red, swollen, and painful, the local skin temperature was increased as evident by touch, and a gouty tophi with a size of about 6 cm × 6 cm could be seen in the right ankle joint. The gouty tophi had broken and secreted white sticky secretions accompanied by scattered odor and severe edema of the right lower limb (Figure 1).

Laboratory examinations were conducted for blood, blood analysis, biochemical tests, coagulation, and levels of serum C-reactive protein, serum procalcitonin, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, brain natriuretic peptide, and ferritin. In addition, we also conducted secretion bacterial culture and bone marrow biopsy. Laboratory data at admission showed a white blood cell count of 26.45 × 109 cells/L, a neutrophil count of 24.57 × 109 cells/L, and serum uric acid level of 535 μmol/L (Table 1). After the fourth operation, laboratory data showed that a white blood cell count of 0.73 × 109 cells/L, a neutrophil count of 0.02 × 109 cells/L, a lymphocyte count of 0.63 × 109 cells/L, hemoglobin levels of 58 g/L, a platelet count of 93 × 109 cells/L, and a ferritin count of 2576.81 ng/mL (Table 1). Local palpation found that the patient's liver and spleen had varying degrees of swelling.

| On admission | After 4th operation | Before discharge | |

| RBC (× 1012/L) | 4.37 | 2.17 | 2.14 |

| WBC (× 109/L) | 26.45 | 0.73 | 4 |

| NEU (× 109/L) | 24.57 | 0.02 | 2.02 |

| LYM (× 109/L) | 0.66 | 0.63 | 1.50 |

| HGB (g/L) | 124 | 58 | 60 |

| Platelet (× 109/L) | 360 | 93 | 112 |

| UA (μmol/L) | 535 | 380 | 416 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 24.3 | 32 | 34.8 |

| AST (U/L) | 18 | 13 | 6 |

| ALT (U/L) | 15 | 13 | 3 |

| PCT (ng/L) | 2.84 | 1.57 | 0.08 |

| ESR (mm/h) | 64 | 67 | 48 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 205 | 168 | 16.8 |

| BNP (pg/L) | 1470.9 | 474.2 | 643.2 |

| D-dimer (mg/L) | 5.54 | 2.93 | |

| Fibrinogen (g/L) | 8.05 | ||

| Ferritin (ng/mL) | 2576.81 |

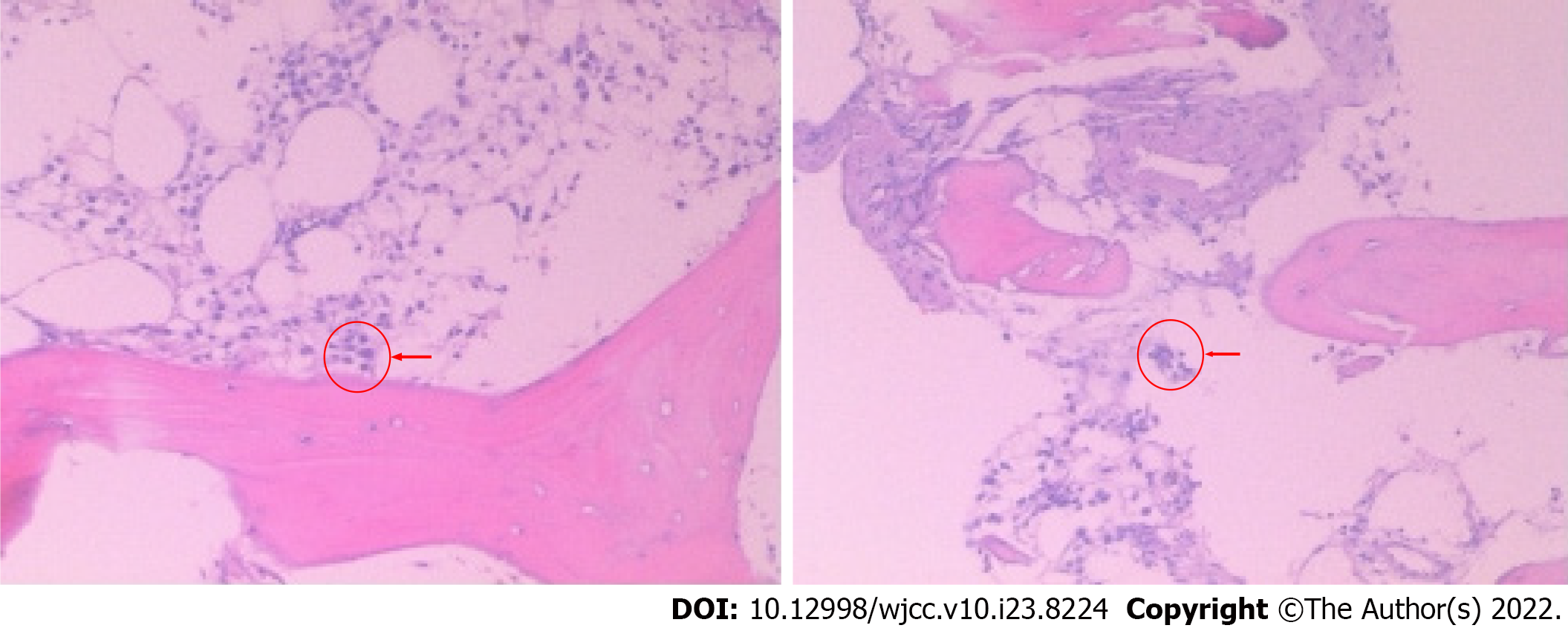

Echocardiography showed decreased left ventricular systolic function (ejection fraction = 30%). The results of bacterial culture of four secretions after operation all indicated that methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) was present. In the late stage of the disease, Candida albicans infection was also found in the secretion culture. Bone marrow puncture results showed that the proliferation ability of bone marrow was decreased, hemophagocytic cells was increased, and granulocytes was decreased (Figure 2).

Consultation opinion on August 10, 2019: At present, the number of leukocytes and neutrophils is abnormally high. This finding and the clinical manifestations suggest the possibility of sepsis. It is suggested that bacterial culture and gram-staining be performed to make a definite diagnosis. Piperacillin sodium and sulbactam sodium for infection (4.5 g q8h iv) was administered for temporary anti-infection treatment. The dosage can be adjusted based on the etiological results and drug sensitivity results.

Consultation opinion on August 13, 2019: The results of the bacterial culture suggest that Staphylococcus methoxycycline-resistant infection is the cause. Vancomycin (0.5 g q12h iv) is suggested as an anti-infection treatment. Attention should be paid to the liver and kidney function of patients, and blood analysis and bacterial culture should be reviewed in time.

Consultation opinion on August 27, 2019: At present, the patient is still feverish (the temperature > 38 °C); and the highest recorded temperature was 39.4 °C. The leukocyte and glomerular filtration rates have improved. Vancomycin (1 g qd iv) combined with piperacillin and zolbactam sodium for injection (4.5 g q8h iv) continues to be used for anti-infection treatment. Currently, the antibiotic program cover common hospital bacteria. It is suggested to use methylprednisolone tablets (12 mg qd po) for symptomatic treatment in patients with fever.

Consultation opinion on September 4, 2019: At present, the wound has healed well, the total number of white blood cells and neutrophils decreased, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein are increased slightly. Considering that the infection is under control, vancomycin has been used for 1 mo, it can be discontinued and replaced with levofloxacin (0.6 g qd iv) for maintenance treatment.

Consultation opinion on September 9, 2019: The patient presents with fever, sore throat, and a body temperature of > 39 °C, laboratory examination indicated a drastic decrease in granulocytes and neutrophil levels, and an increase in infection indexes, such as procalcitonin level, blood sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein level. It is recommended that imipenem and cilastatin sodium injection (0.5 g q8h iv), as well as caspofungin acetate (80 mg qd iv) are used for treatment.

Consultation opinion on September 2, 2019: At present, the patient has high fever and fuzzy consciousness. Blood analysis indicates cytopenias (affecting at least two lineages in the peripheral blood). Local palpation revealed varying degrees of swelling in the patient's liver and spleen. Bone marrow biopsy is suggested to make a definite diagnosis. In case of infection, the use of cytokines to improve white blood cell count can be considered.

Consultation opinion on September 6, 2019: Bone marrow biopsy findings indicate that the proliferation ability of the bone marrow has decreased, hemophilic cells have increased, and granulocytes have decreased. These findings, clinical signs, and the blood test findings, considered together, indicate HPS. It is advised that the patient be transferred to the hematology department for further treatment.

Combined with the results of laboratory examination, bacterial culture, bone marrow biopsy, and consultation of Hematology Department and Pharmacy Department, the patient was diagnosed as: (1) Gouty arthritis; (2) Sepsis; and (3) Hemophagocytic syndrome.

For the treatment of gouty tophi rupture, we conducted five surgical operations for thorough debridement combined with vacuum sealing drainage. The main cause of the disease was infection induced by the rupture of gouty tophi. Therefore, active measures should be taken to control serum uric acid levels throughout the treatment of the disease. We administered febuxostat tablets (40 mg qd po) to inhibit the formation of uric acid, and methylprednisolone tablets (40 mg qd po) to inhibit the inflammatory reaction when the symptoms are serious. For patients with repeated infections, we consulted the pharmacy department to develop a personalized antibiotic use plan for patients. On admission, we collected samples of wound secretion for bacterial culture. Considering the possibility of infection, we empirically used piper acillin sodium and sulbactam sodium for infection (4.5 g q8h iv) for 4 d. Based on the bacterial culture findings of MRSA infection, we replaced the antibiotic with vancomycin (0.5 g q12h iv) for 1 d and performed the first operation on the same day. The patient was given symptomatic treatment for uric acid reduction, detumescence, gastric protection, anti-infection, and nutritional support. The use of vancomycin (1 g q12h iv) was continued for 5 d for anti-infection treatment until the second operation. After the second operation, the patient was given oxygen inhalation, blood volume supplement, anti-thrombotic, anti-infection, and other symptomatic treatment. Additionally, vancomycin (1 g q12h iv) was administered for 4 d to prevent infections. During this period, the patient had a high fever and disturbance of consciousness again, and the laboratory examination indicated that the inflammatory index was elevated. We changed the antibiotics to vancomycin (1 g q12h iv) combined with piperacillin sodium and sulbactam sodium (4.5 g q8h iv) for 5 d. After the third operation, the secretion culture still showed MRSA infection. As such, we continued the vancomycin for injection (1 g q12h iv) combined with piperacillin sodium and sulbactam sodium (4.5 g q8h iv) for 8 d. When the patient's general condition had improved, we performed the fourth operation. After the operation, we maintained the use of vancomycin for 1 d. After the consultation and evaluation of the pharmacy department, we changed the antibiotic to levofloxacin hydrochloride injection (0.6 g qd iv) for 5d and discontinued vancomycin since the patient's infection had been controlled. During this period, the patient suddenly developed agranulocytosis, which may have been caused by drugs, according to the department of hematology. Therefore, we used recombinant human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (100 μg qd iv) for 6 d to improve leukocyte levels. Later, the patient was diagnosed with HPS and was transferred to the department of hematology for treatment. On the 1st day, we administered imipenem cilastatin sodium (1 g q8h iv) combined with moxifloxacin hydrochloride and sodium chloride (0.1 g qd iv) for 1 d. On the 2nd day, we changed the antibiotic regimen to voriconazole (200 mg q12h iv) for 2 d and linezolid (300 mL q12h iv) for 6 d. After treatment, the patient's vital signs gradually stabilized, followed by the performance of the fifth operation. After the operation, the patient was given symptomatic treatment, such as oxygen inhalation, albumin supplement, gastric protection, and nutritional support. No bacterial infection was found in the secretions of patients after the operation. Considering that the related inflammatory indexes were still high, we administered cefoperazone sodium and sulbactam sodium (3 g bid iv) for 9 d.

After 2 mo of treatment, his laboratory indexes finally returned to normal (Table 1), and the right ankle wound healed well. Under the guidance of the physical therapist, the right ankle function gradually recovered. At his 5-mo follow-up in the outpatient department, his right ankle was completely healed, and the joint function was good (Figure 3).

Gouty arthritis, caused by the deposition of monosodium urate crystals in the joints, tendons, and surrounding soft tissues, is characterized by joint swelling, pain, and dysfunction[12,13]. According to a study in Taiwan, 43.6% of patients with gouty arthritis have symptoms of sepsis. Because the early symptoms are joint swelling and severe pain, these are often ignored by clinicians. As such, when these are finally detected, the patients are already experiencing life-threatening symptoms[7]. The main reason for this is that patients with a long history of gout or multiple subcutaneous gouty tophi deposits are prone to local wound ulcers and staphylococcus aureus infection[14]. Staphylococcemia leads to the metastatic infection of inflammatory joints and the deposition of joint crystals, and the local setting of inflammation and effusion induced by monosodium urate provides an environment for the accumulation of blood-borne microorganisms and the growth of bacteria[7]. This explains why our patients repeatedly developed sepsis and septic shock during hospitalization. Sepsis progresses rapidly. Once it occurs, severe anti-inflammatory reactions may easily occur, causing the patients to undergo immune cell apoptosis and eventually become complicated with various diseases[15,16]. This may be the main reason why our patient suddenly developed HPS in the later stages of the disease. Therefore, early prevention, detection, and intervention are key in delaying the disease process. The main basis for the diagnosis of sepsis includes a clear infectious disease, body temperature changes, and associated inflammatory markers[17], Given these, the selection of the appropriate antibiotics is the main link in preventing the further progression of sepsis. Second, we should actively remove infected tissues with obvious lesions and cut off the source of infection[18]. Our patient had an infected - local gout stone ulceration on admission. After admission, the wound appeared red and swollen and was warm to the touch. Laboratory examination revealed that the related inflammatory indices increased sharply. The results of the bacterial culture suggested an MRSA infection. We took the measures quickly. We conducted multidisciplinary consultations to develop an effective antibiotic treatment plan; however, we effectively treated the MRSA infection through surgical removal combined with local negative pressure drainage to remove the infection focus. Although the patient still had an infection and even experienced shock several times during the treatment, the infection was controlled and the patient’s life was saved through active anti-infection treatment, which also proved that our treatment measures were effective. This case provides valuable experience. To improve the prognosis of patients with giant gouty tophi rupture, it is essential to carry out an early bacterial culture of the secretions, cooperate with a multidisciplinary team, and formulate the corresponding anti-infection treatment plan.

HPS is a rare and destructive immune-activated disease. The excessive inflammation in secondary HPS is mainly associated with infectious, autoimmune, or neoplastic diseases. Furthermore, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and MRSA have been reported to be associated with bacterial HPS[11,19,20]. Although there is no relevant study regarding secondary HPS induced by gout stone rupture, we believe that this mainly occurs due to infection with MRSA, causing septic shock, destruction of immune activation, and induction of HPS. Because of the rarity of this situation, it can be easily ignored by most clinicians. Our case provides a good example of this. Although sepsis occurred many times during the treatment period and HPS developed due to immune system damage in the later stage, which induces HPS, our timely review of relevant indicators and multidisciplinary consultation allowed for the active provision of effective treatment measures, ultimately helping the patient recover. Therefore, we believe that for patients with gouty tophi rupture, sepsis, and immune system damage should be considered in the early stage, and to avoid the occurrence of HPS. Moreover, a timely review of relevant laboratory indicators, combined with multidisciplinary consultation is the key to the successful treatment of the disease.

Sepsis complicated with secondary hemophagocytic syndrome induced by gouty tophi rupture is extremely rare in the clinical setting. Timely and accurate diagnosis is very important to save patients' lives.

Thanks to Qing-Ye Zhang, Associate Chief Pharmaceutist, for guiding the formulation of antibiotic regimen; Li-Wen Hu, Associate Chief Physician, for helping diagnose hemophagocytic syndrome and guiding treatment.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Rheumatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): E

P-Reviewer: Deshwal H, United States; Rodrigues AT, Brazil; Romanelli A, Italy S-Editor: Gong ZM L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Gong ZM

| 1. | Wilson L, Saseen JJ. Gouty Arthritis: A Review of Acute Management and Prevention. Pharmacotherapy. 2016;36:906-922. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Goel N, Khanna V, Jain DK, Gupta V. Gouty tophi presenting as multinodular lateral inguinal swelling: A case report. Diagn Cytopathol. 2018;46:801-803. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Qaseem A, McLean RM, Starkey M, Forciea MA; Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians, Denberg TD, Barry MJ, Boyd C, Chow RD, Fitterman N, Humphrey LL, Kansagara D, Manaker S, Vijan S, Wilt TJ. Diagnosis of Acute Gout: A Clinical Practice Guideline From the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166:52-57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Yu KH, Luo SF, Liou LB, Wu YJ, Tsai WP, Chen JY, Ho HH. Concomitant septic and gouty arthritis--an analysis of 30 cases. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2003;42:1062-1066. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Yu KH, Ho HH, Chen JY, Luo SF. Gout complicated with necrotizing fasciitis--report of 15 cases. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2004;43:518-521. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Delle Sedie A, Riente L, Iagnocco A, Filippucci E, Meenagh G, Grassi W, Valesini G, Bombardieri S. Ultrasound imaging for the rheumatologist X. Ultrasound imaging in crystal-related arthropathies. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2007;25:513-517. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Weng CT, Liu MF, Lin LH, Weng MY, Lee NY, Wu AB, Huang KY, Lee JW, Wang CR. Rare coexistence of gouty and septic arthritis: a report of 14 cases. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2009;27:902-906. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Schram AM, Berliner N. How I treat hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in the adult patient. Blood. 2015;125:2908-2914. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 212] [Cited by in RCA: 273] [Article Influence: 27.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ramos-Casals M, Brito-Zerón P, López-Guillermo A, Khamashta MA, Bosch X. Adult haemophagocytic syndrome. Lancet. 2014;383:1503-1516. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 788] [Cited by in RCA: 958] [Article Influence: 87.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Henter JI, Horne A, Aricó M, Egeler RM, Filipovich AH, Imashuku S, Ladisch S, McClain K, Webb D, Winiarski J, Janka G. HLH-2004: Diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;48:124-131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3075] [Cited by in RCA: 3588] [Article Influence: 199.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Xu P, Zeng H, Zhou M, Ouyang J, Chen B, Zhang Q. Successful management of a complicated clinical crisis: A patient with left-sided endocarditis and secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: a rare case report and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:e9451. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Tausche AK, Aringer M. [Gouty arthritis]. Z Rheumatol. 2016;75:885-898. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Dehlin M, Jacobsson L, Roddy E. Global epidemiology of gout: prevalence, incidence, treatment patterns and risk factors. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2020;16:380-390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 885] [Cited by in RCA: 724] [Article Influence: 144.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Bone RC. Sir Isaac Newton, sepsis, SIRS, and CARS. Crit Care Med. 1996;24:1125-1128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 717] [Cited by in RCA: 627] [Article Influence: 21.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Hotchkiss RS, Karl IE. The pathophysiology and treatment of sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:138-150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2810] [Cited by in RCA: 2772] [Article Influence: 126.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, Shankar-Hari M, Annane D, Bauer M, Bellomo R, Bernard GR, Chiche JD, Coopersmith CM, Hotchkiss RS, Levy MM, Marshall JC, Martin GS, Opal SM, Rubenfeld GD, van der Poll T, Vincent JL, Angus DC. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016;315:801-810. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15803] [Cited by in RCA: 17039] [Article Influence: 1893.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 18. | Emergency Medicine Branch Of Chinese Medical Care International Exchange Promotion Association; Emergency Medical Branch Of Chinese Medical Association; Chinese Medical Doctor Association Emergency Medical Branch; Chinese People's Liberation Army Emergency Medicine Professional Committee. [Consensus of Chinese experts on early prevention and blocking of sepsis]. Zhonghua Wei Zhong Bing Ji Jiu Yi Xue. 2020;32:518-530. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ito S, Takada N, Ozasa A, Hanada M, Sugiyama M, Suzuki K, Nagae Y, Inagaki T, Suzuki Y, Komatsu H. Secondary hemophagocytic syndrome in a patient with methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus Aureus bacteremia due to severe decubitus ulcer. Intern Med. 2006;45:303-307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Hoshino C, Satoh N, Sugawara S, Kuriyama C, Kikuchi A, Ohta M. Community-acquired Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia accompanied by rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis and hemophagocytic syndrome. Intern Med. 2007;46:1047-1053. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |