Published online Jul 26, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i21.7509

Peer-review started: December 19, 2021

First decision: February 21, 2022

Revised: February 27, 2022

Accepted: June 13, 2022

Article in press: June 13, 2022

Published online: July 26, 2022

Processing time: 204 Days and 0.4 Hours

Median arcuate ligament syndrome (MALS) is relatively rare and is due to extraluminal compression of the coeliac artery by the median arcuate ligament of the diaphragm. Here, we report a case of MALS found in a patient with abdominal pain and retroperitoneal haemorrhage for education and dissemination.

This article describes a 46-year-old female patient who was admitted to our hospital with abdominal pain as her chief complaint. She had experienced no obvious symptoms but had retroperitoneal bleeding during the course of the disease. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) and noninvasive CT angiography (CTA) led to an initial misdiagnosis of pancreaticoduodenal artery aneurysm (PDAA) causing retroperitoneal hemorrhage. After intraoperative exploration and detailed analysis of enhanced CT and CTA images, a final diagnosis of MALS was made. The cause of the haemorrhage was bleeding from a branch of the gastroduodenal artery, not rupture of a PDAA. The prognosis of MALS combined with PDAA treated by laparoscopy and interventional therapy is still acceptable. The patient was temporarily treated by gastroduodenal suture haemostasis and was referred for further treatment.

MALS is very rare and usually has postprandial abdominal pain, upper abdominal murmur, and weight loss. It is diagnosed by imaging or due to complications. When a patient has abdominal bleeding or PDAA, we should consider whether the patient has celiac trunk stenosis (MALS or other etiology). When abdominal bleeding is combined with an aneurysm, we generally think of aneurysm rupture and hemorrhage first, but it may also be collateral artery rupture and hemorrhage.

Core Tip: Median arcuate ligament syndrome (MALS) is relatively rare and is due to extraluminal compression of the coeliac artery by the median arcuate ligament of the diaphragm. Here, we report a case of MALS found in a patient with abdominal pain and bleeding, for education and dissemination.

- Citation: Lu XC, Pei JG, Xie GH, Li YY, Han HM. Median arcuate ligament syndrome with retroperitoneal haemorrhage: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(21): 7509-7516

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i21/7509.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i21.7509

Median arcuate ligament syndrome (MALS) is a rare disease that results from extraluminal compression of the coeliac artery by the median arcuate ligament of the diaphragm[1]. MALS occurs in 2 per 100000 patients[1-3]. Typical clinical findings include postprandial abdominal pain, upper abdominal murmur, and weight loss. Other symptoms include nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, and fatigue. However, most patients are asymptomatic[4-6]. MALS typically manifests as abdominal pain and weight loss. Although these symptoms are usually found, diagnosis is often late due to the rarity of this syndrome and to other much more common causes for epigastric pain. One known complication of MALS is collateral circulation aneurysm, which mostly occurs in patients with severe stenosis or occlusion of the initial segment of the abdominal artery, including pancreaticoduodenal artery aneurysm (PDAA), abdominal aneurysm, and gastric omentum aneurysm. Among these, PDAA is most common[7]. Here, we describe a patient who was admitted to the hospital for acute abdomen without any symptoms, and had retroperitoneal haemorrhage during the course of the disease; we discuss the evaluation from the consideration of ruptured PDAA haemorrhage to the diagnosis of MALS.

A 46-year-old female patient was admitted to our department on December 12, 2019 due to the presence of abdominal and back pain for 2 d and aggravation of these symptoms for 1 d.

The patient had no obvious inducement for upper abdominal pain or back pain 2 d before admission. Her discomfort was mainly located in the middle and upper left abdomen, and she exhibited persistent, paroxysmal aggravation; no nausea and vomiting; and no fever and chills. At the outpatient department of our hospital one day prior, after first ruling out angina pectoris, the patient was sent to the Department of Cardiology, where cardiac enzyme analyses, electrocardiograms, and other tests were performed to rule out ischemic heart diseases; next, she went to the emergency department of our hospital to undergo laboratory analyses. Amylase levels were normal and routine blood tests showed normal white blood cells and a haemoglobin (Hb) level of 125 g/L. After symptomatic treatment, the patient’s abdominal pain worsened, and she was admitted to the Department of Gastroenterology.

The patient reported no history of chronic abdominal pain, upper abdominal murmur, or weight loss during the disease course. She reported a history of “arrhythmia” for 3 years, and no history of hypertension, diabetes, coronary heart disease, etc.; additionally, she had no history of pancreatitis or abdominal trauma and no family history of genetic diseases.

N/A.

The patient’s body temperature was 36.8 °C, blood pressure was 120/80 mmHg (1 mmHg = 0.133 kPa), and heart rate was 100 beats/min. She had a face of acute ill, painful expression, clear consciousness, mild pallid eyelid conjunctiva, flat abdomen, tenderness and rebound pain throughout the abdomen, no obvious mass, and no muscle tension. No murmurs were heard in the upper abdomen on inhalation or exhalation.

The blood test showed that Hb was 88 g/L, liver and kidney function was normal, C-reactive protein was 12 mg/L, and blood and urinary amylase levels were normal.

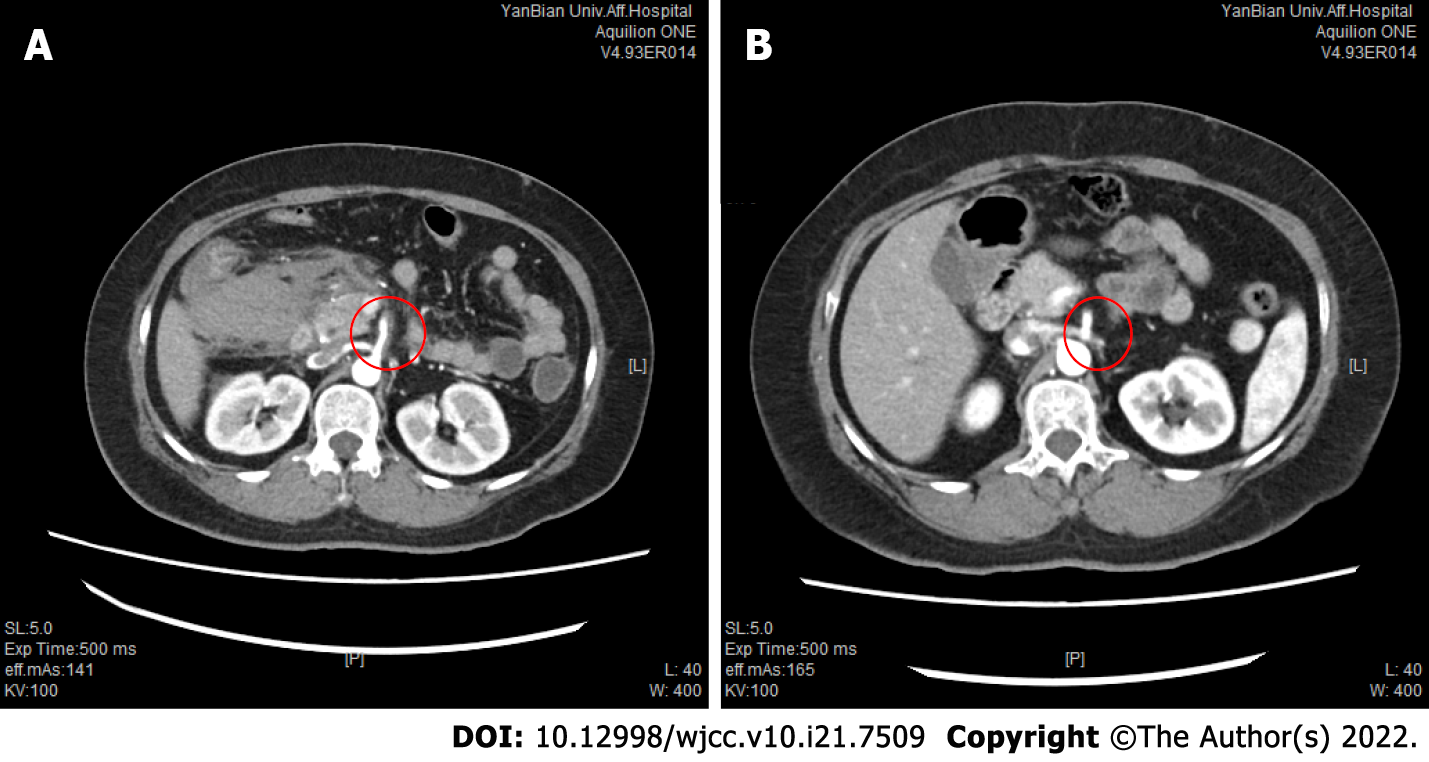

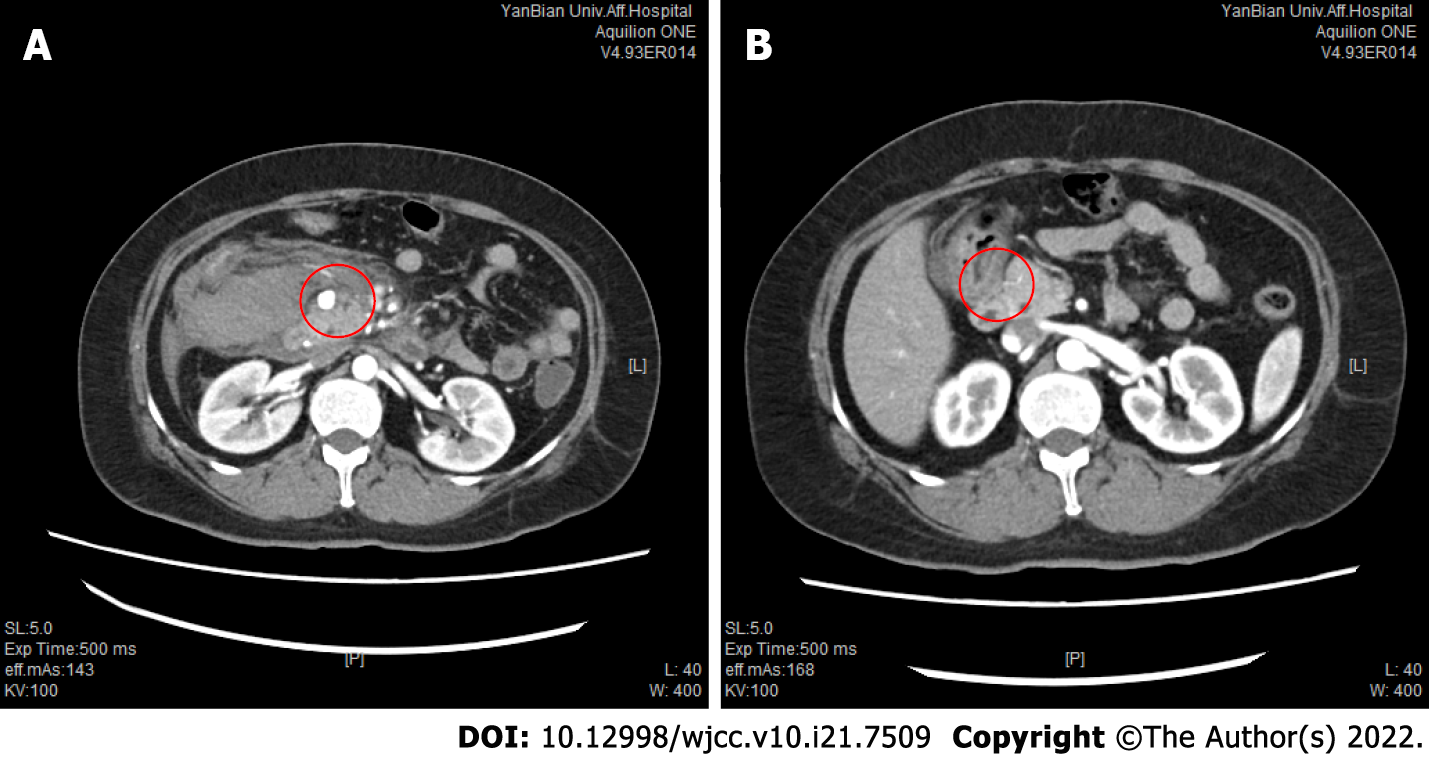

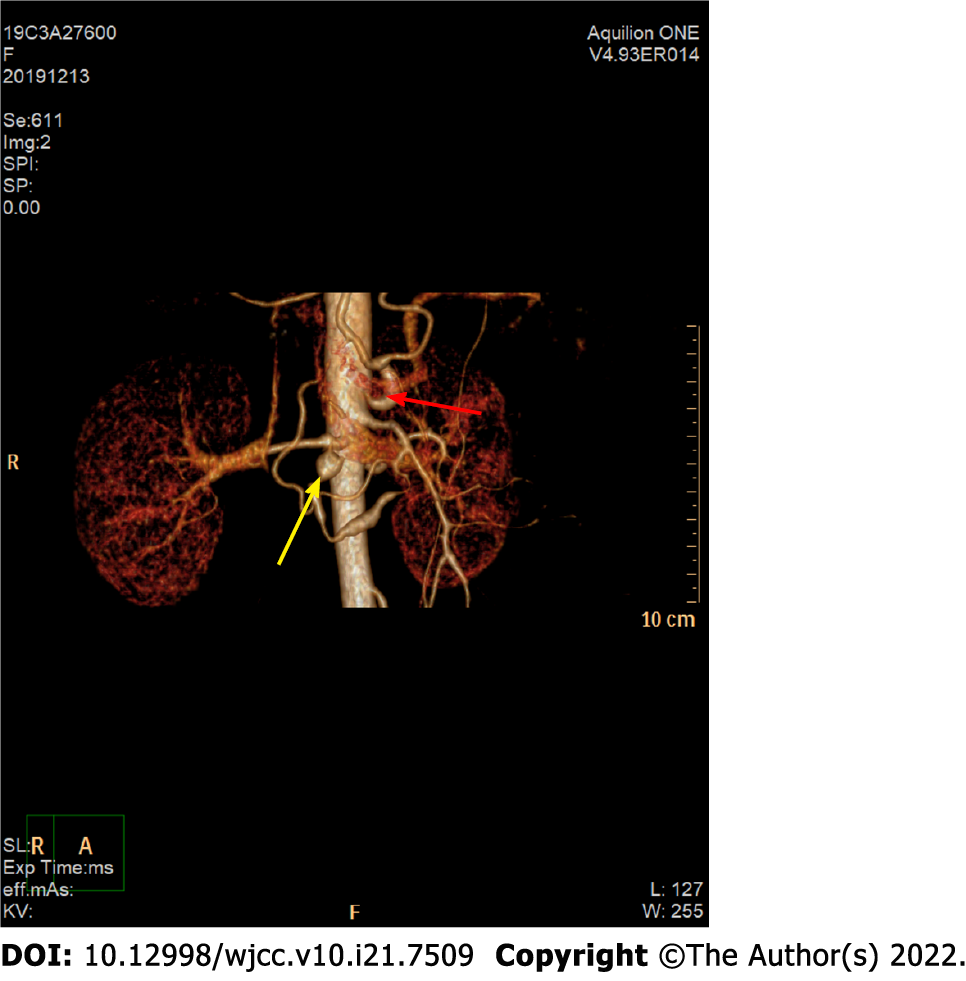

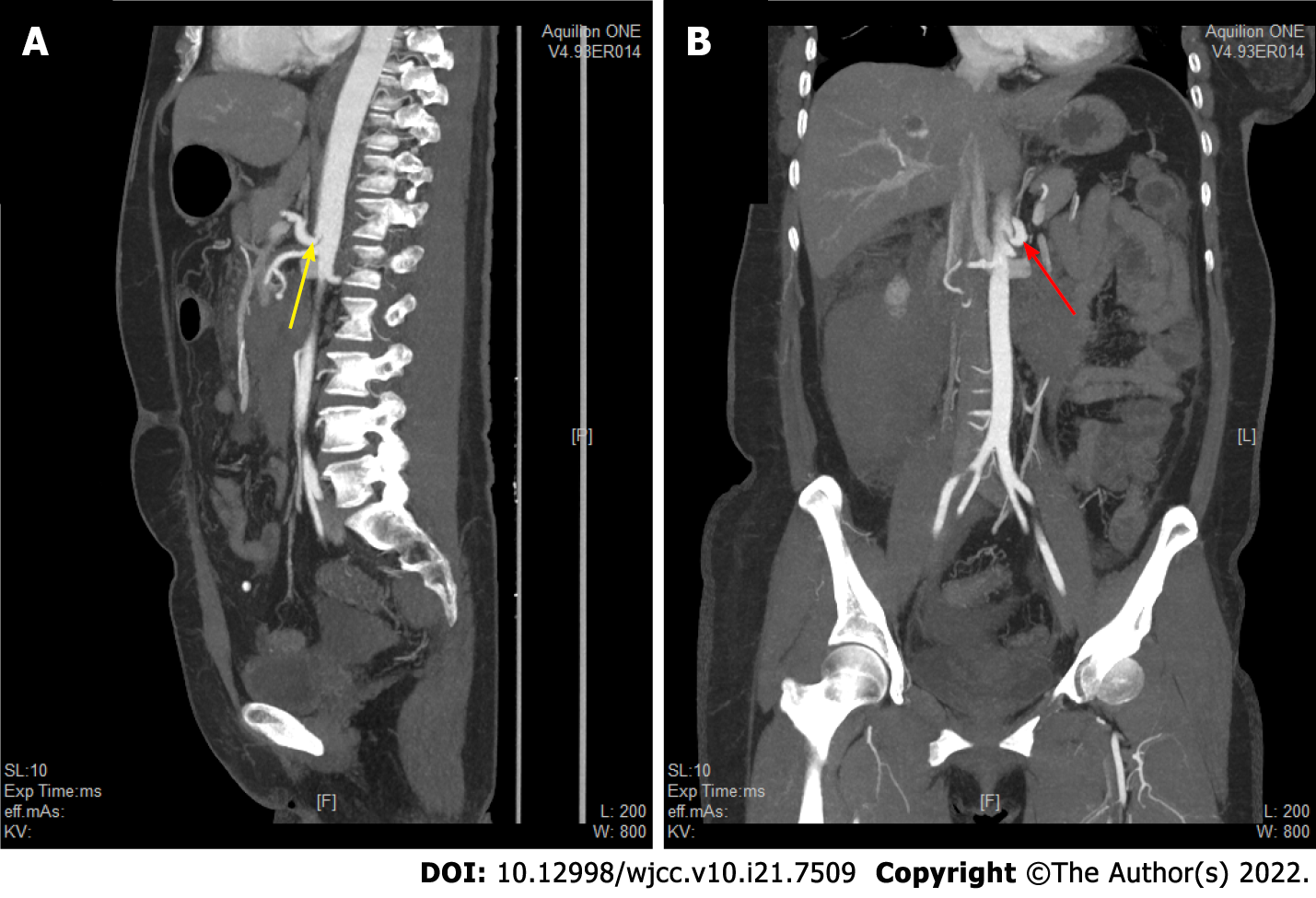

Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen revealed haematomas around the head of the pancreas and retroperitoneum. To further determine the cause of the haematoma, CT and CT angiography (CTA) examinations of the whole abdomen were performed, suggesting a superior mesenteric artery (SMA) mural thrombus (Figure 1A), with stenosis of the lumen, local pancreaticoduodenal artery dilation, 1.2 cm wide diameter (Figure 2A), uneven thickness (Figure 3), and a haematoma around the head of the pancreas and retroperitoneum. Moreover, an abnormal collateral vessel was formed between the gastroduodenal artery and the SMA. The preliminary diagnosis was “retroperitoneal haemorrhage, PDAA, and SMA mural thrombus”. The cause of bleeding was considered to be PDAA rupture. The blood examination showed an Hb level of 69 g/L, and the red blood cell suspension was used to correct anaemia. Because the patient was critically ill and our hospital has not yet performed coil vascular embolism and interventional therapy, surgical exploration was performed in combination with the above conditions.

After layer-by-layer laparotomy, the omentum and gastrocolic ligament were dissociated along the greater curvature of the stomach to expose the retroperitoneal hematoma and remove the hematoma adjacent to the duodenum and above the pancreas. The hepatoduodenal ligament was dissected and the gastroduodenal artery isolated. There was active bleeding approximately 1 cm below the branch of the gastroduodenal artery. PDAA rupture was ruled out due to the location of the bleeding. We read the enhanced CT and the CTA films in detail, and found that the initial segments of the celiac artery and SMA were narrow and that the celiac artery origin was V-shaped (Figures 3 and 4). In addition, abnormal collateral blood vessels were formed between the arteria gastroduodenalis and the SMA.

The final diagnosis was “MALS, retroperitoneal haemorrhage, PDAA, and SMA mural thrombosis”.

Our hospital has not yet performed coil vascular embolism and interventional therapy. Therefore, we did an exploratory laparotomy. After layer-by-layer laparotomy, the omentum and gastrocolic ligament were dissociated along the greater curvature of the stomach to expose the retroperitoneal hematoma and remove the hematoma adjacent to the duodenum and above the pancreas. The hepatoduodenal ligament was dissected and the gastroduodenal artery isolated. The lower branch of the gastroduodenal artery was located above the gastroduodenal artery with active bleeding, and the active bleeding artery were sutured with No. 4 vascular suture needle.

The patient was ventilated for 7 d after the operation and recovered after 13 d. At the 3-mo follow-up, the patient recovered well without obvious discomfort. One year later, the patient was followed without obvious discomfort, and abdominal enhanced CT showed that PDAA disappeared (Figure 2B), SMA mural thrombosis was not observed, and lumen filling was good (Figure 1B). Celiac artery stenosis was still present and the patient was advised to go to a superior hospital for treatment, but the patient refused.

MALS, also known as coeliac artery or axial compression syndrome, is considered a complex disease with multiple aetiologies. The most commonly accepted theory is that coeliac artery pressure leads to decreased blood demand, eventually leading to foregut ischaemia[8]. The compression of the abdominal cavity by the median arch ligament and the resulting intestinal ischaemia usually lead to collateral circulation of the SMA branch. Providing connections between and increased flow through these vessels may lead to the formation of a PDAA[9].

MALS is more common in females than males and occurs mostly between 20 and 50 years of age[10]. Most patients are asymptomatic, and typical imaging findings of MALS are found during a medical examination or after complications develop. In our case, the patient was asymptomatic in the early stages, and she experienced abdominal pain due to bleeding from a ruptured branch of the gastroduodenal artery. When we focused on the retroperitoneal haemorrhage, it was easy to miss a rare abnormal vascular anatomy, such as MALS, which was the initial condition. Thus, we failed to discover MALS. When considering the cause of the patient's PDAA after surgery, we carefully reviewed the patient's enhanced CT and CTA images and found typical imaging manifestations consistent with MALS and a sharp “V” depression of the upper edge of the proximal tube wall of the celiac trunk. In radiology, the detection rate of MALS is relatively low, which may also be due to the difficulty of detecting the main abdominal stenosis by conventional axial and coronary CT reconstruction. If there is no obvious congestive collateral circulation, radiologists also tend not to report stenosis of the celiac axis with only collateral circulation (unless this condition is accompanied by an aneurysm in asymptomatic patients) because they are not familiar with the clinical significance of the disease[5].

The diagnosis of MALS is difficult (particularly when based on clinical manifestations alone) and is reached after excluding other common causes of abdominal pain. If MALS is suspected, conventional angiography, CTA, and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) can be used to verify the location of the celiac trunk. A common form of MALS screening is Doppler ultrasound[11,12], which shows stenosis if the proximal blood flow in the abdominal cavity is disrupted or increased. The advantages of Doppler ultrasound include its non-invasiveness and ease of operation. Although conventional angiography is considered the gold standard for the diagnosis of MALS, angiography has been largely replaced by CTA and MRA[13]. CTA is a very effective diagnostic method. The 3D reconstruction of CTA can clearly show the location and degree of celiac artery stenosis. The sagittal position is the best plane for observing the thickened median arcuate ligament and characteristic hooked stenosis. The coronary surface is more conducive to spatial tracking of the arteries[14]. Because this patient had haemorrhage, to determine the cause of the bleeding and observe the surrounding blood vessels, we performed full abdominal enhanced CT and CTA examinations, and reached a clear diagnosis of MALS with PDAA and SMA mural thrombosis.

Common complications of MALS are collateral aneurysms, including PDAA, abdominal aneurysm, and gastric omental aneurysms. Among them, PDAA is the most common[7], and it has been reported that gastroparesis is also a complication of MALS[11]. We review the reports of MALS published in the past five years in PubMed Central (PMC) and found that 12 articles reported MALS combined with retroperitoneal haemorrhage. The cause of haemorrhage was PDAA rupture and bleeding in ten cases[1,15-23], right gastric aneurysm rupture in one[4], and aneurysm rupture in the arc of Bühler in another one[24]. In the present case, the patient’s condition was complicated by a PDAA with retroperitoneal haemorrhage, and the cause of the bleeding was not related to the PDAA. In addition, the patient formed abnormal collateral circulation blood vessels between the gastroduodenal artery and the SMA, because of coeliac artery stenosis. The blood flow and pressure on the branch vessel wall of the gastroduodenal artery were too large, and finally the vessel wall ruptured, resulting in bleeding.

The treatment of MALS aims to restore normal blood flow to the celiac trunk and prevent the reformation of compression. Laparoscopy and open surgical decompression are two treatment options for MALS. Laparoscopy is being adopted by an increasing number of people due to its advantages such as shortening the length of hospital stay, reducing the risk of postoperative complications, decreasing blood loss, and minimizing postoperative pain. Laparoscopy advocates four operative approaches for MALS: coeliac artery decompression and celiac gangliectomy or coeliac artery dilation or coeliac artery reconstruction, and coeliac artery endovascular stent placement[25]. After laparoscopic or open operative decompression, the patient has a good prognosis, and the cure rate is approximately 80%[12]. For the management of patients with MALS who have a concurrent PDAA, there are currently no treatment guidelines. It has been reported that the two conditions must be treated at the same time. However, considering the morbidity and mortality related to surgery, laparoscopy and endovascular techniques are less invasive treatments and have advantages over open surgery[26]. In our case, considering the actual situation in our hospital, we could only choose surgical suture haemostasis, which saved the patient's life. Although this intervention failed to achieve a complete cure, it provided the patient with an opportunity for the next step of treatment, such as laparoscopic and interventional therapy. Interestingly, in our case, PDAA and SMA thrombosis disappeared after more than 1 year of follow-up after gastroduodenal artery suture hemostasis, suggesting that postoperative pressure on the celiac artery and SMA was reduced to some extent and blood flow was improved. The patient was satisfied with the short-term outcome, but long-term follow-up is still required.

MALS is very rare. It is generally asymptomatic and is diagnosed after the development of complications. In the present case, MALS was missed because, at that time, we did not fully understand the disease. The treatment for MALS with aneurysms is mainly surgical or interventional therapy, but surgical decompression can not only decompress the coeliac artery, but also eliminate the formed aneurysms, with good prognosis.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, General and Internal

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Hanaki T, Japan; Hanaki T, Japan; Tenreiro N, Portugal A-Editor: Yao QG, China S-Editor: Chang KL L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Chang KL

| 1. | Hanaki T, Fukuta S, Okamoto M, Tsuda A, Yagyu T, Urushibara S, Endo K, Suzuki K, Nakamura S, Ikeguchi M. Median arcuate ligament syndrome and aneurysm in the pancreaticoduodenal artery detected by retroperitoneal hemorrhage: A case report. Clin Case Rep. 2018;6:1496-1500. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Mehta A, Bath AS, Ahmed MU, Kenth S, Kalavakunta JK. An Unusual Presentation of Median Arcuate Ligament Syndrome. Cureus. 2020;12:e9131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Foertsch T, Koch A, Singer H, Lang W. Celiac trunk compression syndrome requiring surgery in 3 adolescent patients. J Pediatr Surg. 2007;42:709-713. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Toriumi T, Shirasu T, Akai A, Ohashi Y, Furuya T, Nomura Y. Hemodynamic benefits of celiac artery release for ruptured right gastric artery aneurysm associated with median arcuate ligament syndrome: a case report. BMC Surg. 2017;17:116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Heo S, Kim HJ, Kim B, Lee JH, Kim J, Kim JK. Clinical impact of collateral circulation in patients with median arcuate ligament syndrome. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2018;24:181-186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sempere Ortega C, Gallego Rivera I, Shahin M. Gastric ischaemia as an unusual presentation of median arcuate ligament compression syndrome. BJR Case Rep. 2017;3:20160005. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Tracci MC. Median arcuate ligament compression of the mesenteric vasculature. Tech Vasc Interv Radiol. 2015;18:43-50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Okada H, Ehara K, Ro H, Yamada M, Saito T, Negami N, Ishido Y, Sato M. Laparoscopic treatment in a patient with median arcuate ligament syndrome identified at the onset of superior mesenteric artery dissection: a case report. Surg Case Rep. 2019;5:197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Takase A, Akuzawa N, Hatori T, Imai K, Kitahara Y, Aoki J, Kurabayashi M. Two patients with ruptured posterior inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery aneurysms associated with compression of the celiac axis by the median arcuate ligament. Ann Vasc Dis. 2014;7:87-92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Sapadin A, Misek R. Atypical Presentation of Median Arcuate Ligament Syndrome in the Emergency Department. Clin Pract Cases Emerg Med. 2019;3:413-416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Sun Z, Zhang D, Xu G, Zhang N. Laparoscopic treatment of median arcuate ligament syndrome. Intractable Rare Dis Res. 2019;8:108-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ozel A, Toksoy G, Ozdogan O, Mahmutoglu AS, Karpat Z. Ultrasonographic diagnosis of median arcuate ligament syndrome: a report of two cases. Med Ultrason. 2012;14:154-157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kuruvilla A, Murtaza G, Cheema A, Arshad HMS. Median Arcuate Ligament Syndrome: It Is Not Always Gastritis. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep. 2017;5:2324709617728750. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Baskan O, Kaya E, Gungoren FZ, Erol C. Compression of the Celiac Artery by the Median Arcuate Ligament: Multidetector Computed Tomography Findings and Characteristics. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2015;66:272-276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Rebelos E, Cipriano A, Ferrini L, Trifirò S, Napoli N, Santini M, Napoli V. Spontaneous bleeding of the inferior pancreatic-duodenal artery in median arcuate ligament syndrome: do not miss the diagnosis. Oxf Med Case Reports. 2019;2019. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Terayama T, Tanaka Y, Soga S, Tsujimoto H, Yoshimura Y, Sekine Y, Akitomi S, Ikeuchi H. The benefits of extrinsic ligament release for potentially hemodynamically unstable pancreaticoduodenal arcade aneurysm with median arcuate ligament syndrome: a case report. BMC Surg. 2019;19:50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Tokuda S, Sakuraba S, Orita H, Sakurada M, Kushida T, Maekawa H, Sato K. Aneurysms of Pancreaticoduodenal Artery due to Median Arcuate Ligament Syndrome, Treated by Open Surgery and Laparoscopic Surgery. Case Rep Surg. 2019;2019:1795653. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Chen YC, Tsai HL, Yeh YS, Huang CW, Chen IS, Wang JY. A huge intra-abdominal hematoma with an unusual etiology. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2019;30:565-568. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Sakatani A, Doi Y, Kitayama T, Matsuda T, Sasai Y, Nishida N, Sakamoto M, Uenoyama N, Kinoshita K. Pancreaticoduodenal artery aneurysm associated with coeliac artery occlusion from an aortic intramural hematoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:4259-4263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Miyayama S, Terada T, Tamaki M. Ruptured pancreaticoduodenal artery aneurysm associated with median arcuate ligament compression and aortic dissection successfully treated with embolotherapy. Ann Vasc Dis. 2015;8:40-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Yamana F, Ohata T, Kitahara M, Nakamura M, Yakushiji H, Nakahira S. Blood flow modification might prevent secondary rupture of multiple pancreaticoduodenal artery arcade aneurysms associated with celiac axis stenosis. J Vasc Surg Cases Innov Tech. 2020;6:41-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Storm J, Kerr E, Kennedy P. Rare complications of a low lying median arcuate coeliac ligament. Ulster Med J. 2015;84:107-109. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Kimura N, Matsui K, Shibuya K, Yoshioka I, Naruto N, Hoshino Y, Mori K, Hirano K, Watanabe T, Hojo S, Sawada S, Okumura T, Nagata T, Noguchi K, Fujii T. Metachronous rupture of a residual pancreaticoduodenal aneurysm after release of the median arcuate ligament: a case report. Surg Case Rep. 2020;6:34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Abe K, Iijima M, Tominaga K, Masuyama S, Izawa N, Majima Y, Irisawa A. Retroperitoneal Hematoma: Rupture of Aneurysm in the Arc of Bühler Caused by Median Arcuate Ligament Syndrome. Clin Med Insights Case Rep. 2019;12:1179547619828716. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Fujiwara Y, Higashida M, Kubota H, Watanabe Y, Ueno M, Uraoka M, Okamoto Y, Mineta S, Okada T, Tsuruta A, Kusunoki H, Ueno T. Laparoscopic treatment of median arcuate ligament syndrome in a 16-year-old male. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2018;52:79-83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Miyamotto M, Kanegusuku CN, Okabe CM, Claus CMP, Ramos FZ, Rothert Á, Gubert APN, Moreira RCR. Laparoscopic treatment of celiac axis compression by the median arcuate ligament and endovascular repair of a pancreaticoduodenal artery aneurysm: case report. J Vasc Bras. 2018;17:252-256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |