Published online Jul 26, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i21.7451

Peer-review started: October 31, 2021

First decision: December 27, 2021

Revised: December 29, 2021

Accepted: June 15, 2022

Article in press: June 15, 2022

Published online: July 26, 2022

Processing time: 252 Days and 18.1 Hours

Tuberculosis (TB) remains one of the highest Asia’s health problems. Spondylitis TB in diabetes mellitus (DM) and hypothyroidism patients is a rare case of extrapulmonary tuberculosis. However, there is a lack of therapeutic guidelines to treat spondylitis TB, particularly with type 2 DM (T2DM) and hypothyroidism as comorbidities. Here we present a case of spondylitis TB with T2DM and hypothyroidism in a relatively young patient and its therapeutic procedure.

We report the case of a 35-year-old male patient from Surabaya, Indonesia. Based on anamnesis, physical examination, and magnetic resonance imaging, the patient has been categorized in stage II of spondylitis TB with grade 1 paraplegia. Surprisingly, the patient also had a high HbA1c level, high thyroid stimulating hormone, and low free T4 (FT4), which indicated T2DM and hypothyroidism. A granulomatous process was observed in the histopathological section. The antituberculosis drugs isoniazid and rifampicin were given. In addition, insulin, empagliflozin, and linagliptin were given to control hyperglycemia conditions, and also levothyroxine to control hypothyroidism.

The outcome was satisfactory. The patient was able to do daily activities without pain and maintained normal glycemic and thyroid levels. For such cases, we recommend the treatment of spondylitis TB by spinal surgery, together with T2DM and hypothyroidism therapies, to improve the patients’ condition. Prompt early and non-invasive diagnoses and therapy are necessary.

Core Tip: Mycobacterium tuberculosis is an infectious pathogen that causes pulmonary and extrapulmonary tuberculosis. We herein present a case of spondylitis tuberculosis in a 35-year-old patient with diabetes mellitus and hypothyroidism that had just known when the patient was hospitalized. Mycobacterium tuberculosis was isolated from both the capsule and pus of the surgically excised abscess in the spinal cord at T9-10 levels. This case highlights the ultimate importance to do prompt early and non-invasive diagnoses and therapy in extrapulmonary tuberculosis.

- Citation: Novita BD, Muliono AC, Wijaya S, Theodora I, Tjahjono Y, Supit VD, Willianto VM. Managing spondylitis tuberculosis in a patient with underlying diabetes and hypothyroidism: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(21): 7451-7458

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i21/7451.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i21.7451

Tuberculosis (TB) remains one of the highest Indonesia’s health problems. In 2016, the incidence of TB in Indonesia reached 647/100000 population, which rose almost two times from the previous year[1]. Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) may lead to untoward consequences of excessive inflammatory reaction and result in severe tissue damage[2]. Pott disease, also known as spondylitis TB, is an example of extrapulmonary tuberculosis (EPTB) manifestation that was first described by Percival Pott in 1775[3]. The EPTB incidence rate in Indonesia reaches 1%-5% of the worldwide TB cases[4].

Spondylitis TB represents bone destruction due to inflammatory reaction against Mtb and usually presents in patients affected by predisposing immunosuppressive conditions[5]. Diabetes mellitus (DM) is one of the most common premorbid to spondylitis TB due to chronic hyperglycemia that is related to dysfunction of the immune response. Most of spondylitis TB cases in patients with DM relate to diabetic foot with mycobacterial infection and psoas abscess formation[6,7]. The advanced stage of spondylitis TB relates to deformity and neurological deficit and this condition becomes a burden to the patient. Therefore, early detection, early treatment, and risk factor control of the disease give a better prognosis for the patient[8].

Back pain and limb weakness are the most clinical symptoms of spondylitis TB. Laurence Le Page and coworkers found that back pain was the most common symptom (95% of cases) and neurological symptoms were present in 74% of cases[9]. Suzaan Marais and coworkers found that lower limb weakness was the most frequent symptom in patients. Fever is rarely occurring in spondylitis TB, unlike pyogenic spondylitis that has high fever symptom[10]. Kyphosis and spinal cord compressions are the most common complications of spondylitis TB. However, there is a lack of therapeutic guidelines to treat spondylitis TB, particularly with type 2 DM (T2DM) and hypothyroidism as comorbidities. Here we present a case of spondylitis TB in a relatively young male patient (35 years old) with T2DM and hypothyroidism and its therapeutic procedure. We demonstrated that the immediate treatment of this patient according to the WHO consolidated guidelines on extrapulmonary tuberculosis (EPTB), in conjunction with spinal surgery, followed by subsequent hypothyroidism treatment and diabetes treatment, could successfully improve the patient’s condition.

A 35-year-old Asian male patient from Surabaya, Indonesia presented to the Emergency Medicine Department of the hospital complaining of worsening low back pain, urinary retention, limb paraparesis, and paresthesia.

Limb paresthesia got worse around a week before being hospitalized. The patient did not have episodes of fever, and he maintained good physical well-being in terms of appetite and weight.

The patient had a history of T2DM around 2 years. He did not have any past history of chronic productive cough, pulmonary tuberculosis, or any contact with another TB patient.

The patient was a heavy smoker.

In the physical examination, the patient showed a kyphotic posture and normal vital signs. The neurological examination showed significant impairment of motoric quality, paresthesia at T6-7 levels, pressure pain at T5-7 levels, and restriction of cervical movement.

Laboratory investigations showed that in this case, the infection was related with a predominant higher neutrophil count and mild normochromic normocytic anemia (Table 1).

| Parameter | Day 0 (patient admission) | Day 5 post admission (several hours before spinal surgery) | Day 8 post admission (day 3 after spinal surgery) | 6 mo after spinal surgery | Reference | Unit |

| Leukocytes | 15.300 | 10.600 | 12.000 | 6.390 | 3.600 -10.600 | X cells/μL |

| Neutrophils | 7.840 | 8.000 | 7.580 | 5.900 ↓ | 5.000–7.500 | X cells/μL |

| Lymphocytes | 8.34 | 7.68 | 8.25 | 19.2 | 18 - 42 | % |

| Monocytes | 10.3 | 9.09 | 9.55 | 12.4 | 2 - 11 | % |

| Eosinophils | 2.54 | 2.78 | 5.49 | 7.62 | 0 - 3 | % |

| Basophils | 0.75 | 0.33 | 1.26 | 1.76 | 0 - 2 | % |

| Hemoglobin | 10.9 | 9.3 | 10.4 | 10.8 | 13.0 -18.0 | g/dL |

| MCV | 81.5 | 80,8 | 82.3 | 80.5 | 80 - 100 | fL |

| Thrombocytes | 365.000 | 329.000 | 297.000 | 258.000 | 150.000 - 450.000 | /μL |

| MPV | 7.03 | 6.9 | 6.89 | 6.82 | 6.5-12.0 | fL |

| Hs-CRP | 47.9 | NT | NT | NT | 0.3-10.0 | mg/L |

| TSH | 5.6781 | NT | NT | 2.6491 ↓ | 0.35 – 4.94 | uIU/mL |

| FT4 | 0.84 | NT | NT | 1.00 ↑ | 0.70 – 1.48 | ng/dL |

| Lumbar biopsy(microscopical examination) | Granulomatous process was observed, consistent with tuberculous infection | |||||

| Postprandial plasma glucose | 473 | 345 | NT | 186 ↓ | 120-200 | mg/dL |

| Pre-prandial plasma glucose | 199 | 186 | NT | NT | 70-140 | mg/dL |

| HbA1c | 9.9 | NT | NT | 6.6 ↓ | < 6.0 | % |

| Drug sensitivity | Rifampicin sensitive | |||||

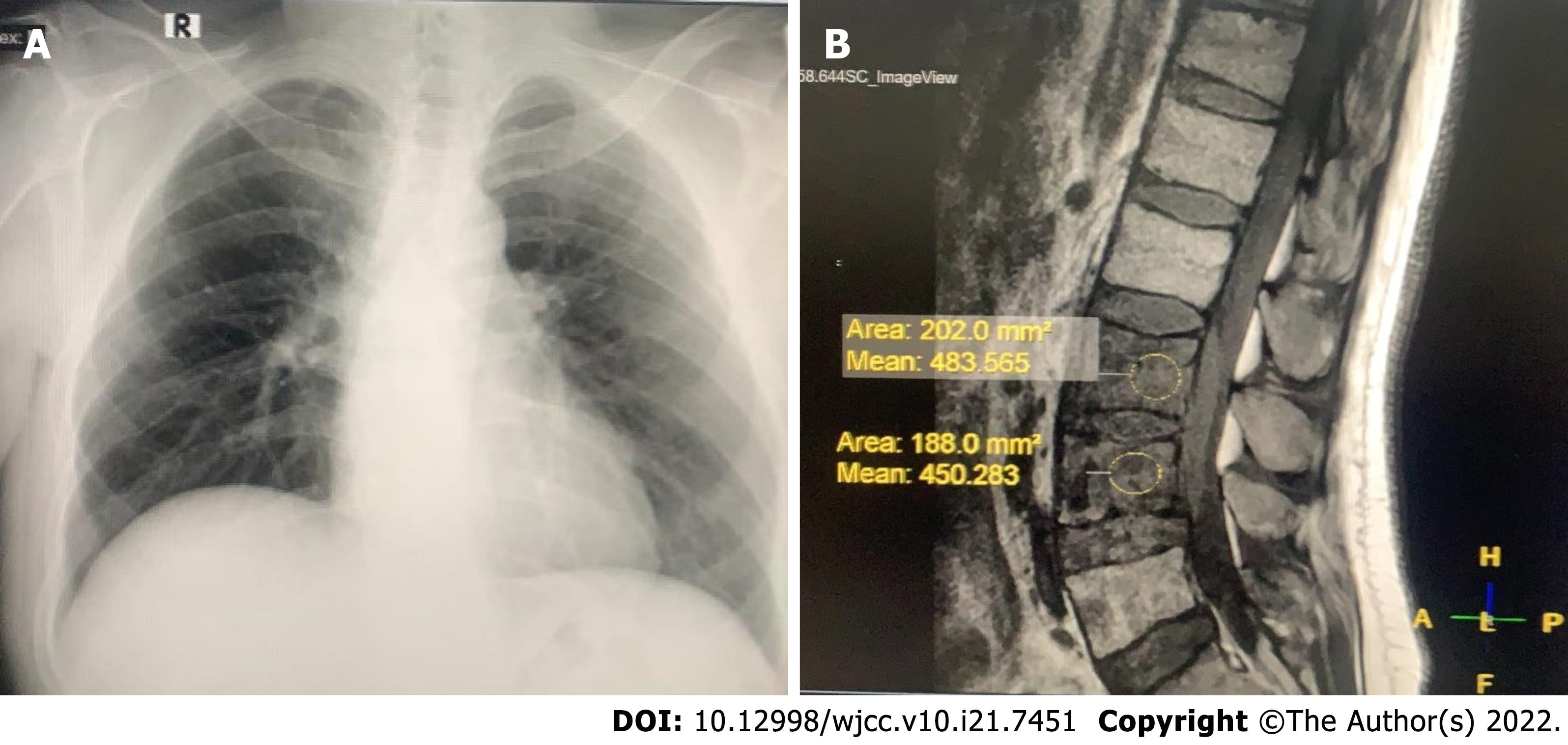

The lungs were clear, with no masses, granulomas, nodules, consolidation, or collapse visible (Figure 1A). However, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the spine showed a kyphotic thoracic curve, vertebral body destruction at C6, bulging abscess at T9-10, paravertebral abscess formation at L3-4, and abscess extension to the anterior spinal canal (Figure 1B). After spinal surgery, T9-10 remained kyphotic with no bone oedema (Figure 2).

To identify the etiological factor for the patient’s spinal abscess, histopathology examination and direct smear were done, which showed positive results for TB. The bacteria were sensitive to rifampicin (RIF) and isoniazid (INH).

The final diagnosis of the presented case was spondylitis TB with T2DM and hypothyroidism.

On admission, the antituberculosis drugs isoniazid INH 5 mg/kg body weight (BW) and RIF 10 mg/kg BW were given daily. In addition, 20 mg/kg BW of ethambutol and pyrazinamide were given three times a week, according to the WHO category I standardized “9-mo therapy” for EPTB. The patient underwent spinal surgery on December 14, 2020 (Figure 2). To lessen the pain, 25 mg of Lyrica (pregabalin) and amitriptyline, and intravenous injection of 1 g metamizole were given after spinal surgery. In this case, corticosteroid could not be used due to very high plasma glucose levels. To treat the hypothyroidism, 50 mcg of Euthyrox (levothyroxine) was given. Six months after spinal surgery, the patient did not feel any pain, and his condition was improved. Therefore, the patient was given only amitriptyline and antituberculosis drugs with additional diabetes treatment for the following 3 mo. To control the diabetes, Novo (rapid acting insulin) 8 IU three times a day and Tresiba (long-acting insulin) 14 mg IU once daily were given. Besides, Trajenta (linagliptin) 5 mg and Jardiance (empagliflozin) 25 mg were given daily.

The overall results were satisfactory. The patient’s condition was significantly improved until now, with no sign of EPTB. The patient was able to do daily activities without pain and maintained normal glycemic and thyroid levels.

The patient presented herein was relatively young (35 years old), with no history of chronic productive cough, pulmonary TB, or any contact with TB patients. To our knowledge, this is a very rare case report of spondylitis TB in young adults who presented with T2DM and hypothyroidism as comorbidities. Maturity Onset Diabetes of The Young (MODY) was one of the possible cause. However, there was no data on homeostatic model assessment (HOMA)-A and HOMA-B. In this paper, we propose the therapeutical guidelines to treat spondylitis TB with T2DM and hypothyroidism as comorbidities. Insulin is still the golden standard for therapy of MODY. The combination of insulin, empagliflozin, and linagliptin showed successful outcome to control the patient’s chronic hyperglycemia from HbA1c 9.9% at day 0 to 6.6% at 6 mo after surgery (Table 1). The treatment with levothyroxine also showed successful outcome in controlling hypothyroidism condition; as shown in Table 1, high thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) and low FT4 level became normal.

Spondylitis TB is the most common and serious form of secondary hematogenous skeletal infection, originating from the primary site of infection, most commonly the lungs. In accordance to the MRI results (Figure 1B), spondylitis TB commonly involves lower thoracic spine (40-50%), followed by lumbar spine (35%-45%) and cervical spine (10%)[6]. Mtb bacteria could reach the spine by hematogenous spread, so the vertebral bodies are usually affected first. The bacteria stimulated our immune response and infected our inflammatory cells, subsequently forming granuloma[11].

Spinal TB is initially apparent in the anterior inferior portion of the vertebral body. In the early stage of spondylitis TB, the disc space is preserved because of the lack of proteolytic enzyme[12]. Later on, it spreads into the central part of the body or disc. The infection causes pain and bone destruction, making the vertebral bodies collapsed, leading to kyphosis deformity. The kyphosis deformity could manifest as various types, such as knuckle deformity (single vertebra collapse), gibbus deformity (collapse of two or three vertebrae), or global rounded kyphosis (involvement of multiple adjacent vertebrae)[13]. The infection can spread to anterior and posterior longitudinal ligaments to the adjacent levels[11].

Sometimes, nerve roots may be compressed, causing neurologic pain along the roots. Neurological deficit can occur in early active disease due to spinal cord or cauda equina compression by inflammatory tissues, epidural abscess, protruded intervertebral disc, or spinal subluxation. In late-onset neurologic deficit, it occurs years after active TB infection, which is caused by severe kyphosis making chronic spinal cord or cauda equina compression[13]. Thus, surgery is required to achieve debridement and drainage of large cold abscesses, decompression of the spinal cord and neural structures, prevention of instability, and correction or prevention of deformity.

The risk factors for spondylitis TB vary widely. The incidence of spondylitis TB is higher in endemic areas and environments that support the spread of Mtb. The incidence also increases in populations experiencing malnutrition, dense and slum areas, low levels of education, and poor sanitation. This condition is common in developing countries[14]. The prevalence of spondylitis TB increases in patients with certain conditions and comorbidities, such as pulmonary TB, previous history of TB infection, history of long-term glucocorticoid treatment, DM comorbidity, chronic kidney disease, and human immunodeficiency virus infection. Men are also included in the population at risk for spinal TB, and this may be due to occupational and lifestyle factors[13,15,16].

T2DM is a comorbidity that can both accelerate TB and complicate TB treatment[17]. Poor glycemic control could increase disease severity among TB patients. In EPTB, bone disease was the most common form found in patients with DM[18]. Hyperglycemia affects innate and adaptive immune responses against Mtb, through impairment of phagocytosis[19]. Chronic hyperglycemia causes enhanced production of sorbitol and fructose and activation of the polyol pathway, and increases the formation of AGEs and production of reactive oxygen species[20]. DM affects the production of interferon γ and interleukin (IL)-12, as well as the proliferation of T cells. Interferon works to initiate the process of killing bacteria by macrophages via nitric oxide. Decreased levels of IL-12 result in a lack of mobility of leukocytes (macrophages and T cells) in neutralizing infectious agents. Lymphocyte proliferation has a main role in activation of antigen presenting cells. Whenever lymphocytes are unable to form adequate antibodies against TB, Mtb applies its escape mechanism. Hyperglycemia is also related to humoral immune defects, deficiency of complement proteins C3, C4, and C1 inhibitors, and changes to antibody formation. Thus, hyperglycemia decreases the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-2, IL-8, and TNF). Therefore, the risk of EPTB amongst patients with DM is three time higher and the rate of anti-tuberculosis failures is two times higher than those in the general population[17].

Thyroid dysfunction and DM are two of the most frequent chronic endocrine disorders with variable prevalence among different populations. It is well known that type 2 DM and hypothyroidism often tend to coexist. Subclinical hypothyroid frequently happens in DM (around 20%)[21]. Hypothyroid condition relates to poor glycemia index due to regulation of hepatic glucose and impaired glucose absorption. Moreover, hypothyroidism is also associated with multidrug resistant TB[22]; however, the mechanism remains unclear. The coexistence of hypothyroidism in a spondylitis TB patient presented in this manuscript could be induced by anti-tuberculosis drugs INH and RIF23. Poor glycemia index as a clinical manifestation of hypothyroidism could be another cause of ineffective tuberculosis therapy. Thus, treatment of hypothyroidism in patients with DM using levothyroxine is necessary. Beside levothyroxine, treatment of hypothyroidism with insulin could enhance the FT4 concentration in blood, and modulate thyrotropin releasing hormone and TSH levels.

Taken together, spondylitis TB is the most common and serious form of secondary hematogenous skeletal TB. To our knowledge, this is the first case report of a spondylitis TB young man with T2DM and hypothyroidism as comorbidities in Surabaya, Indonesia. T2DM and hypothyroidism tend to coexist together. In addition, those comorbidities can both accelerate TB and complicate TB treatment. The treatment combination presented here with levothyroxine, insulin, empagliflozin, and linagliptin, in addition to spinal surgery, could improve the TB therapy. In this case, the usage of corticosteroid drugs was avoided due to very high plasma glucose levels. Early monitoring and intensive evaluation of patients with spondylitis TB, particularly those with diabetes and hyperthyroidism as comorbidities, are very pivotal to improve the therapy.

We would like to thank the patient who gave us permission to report this case, all doctors involved in this case, and Premier Hospital Surabaya that gave us data.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: Faculty of Medicine, Widya Mandala Catholic University Surabaya.

Specialty type: Infectious diseases

Country/Territory of origin: Indonesia

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Belosludtseva NV, Russia; Tuan Ismail TS, Malaysia S-Editor: Xing YX L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Depkes RI. InfoDatin Tuberculosis. Kementeri Kesehat RI. Published online 2018: 1-10.. |

| 2. | Evans DJ. The use of adjunctive corticosteroids in the treatment of pericardial, pleural and meningeal tuberculosis: do they improve outcome? Respir Med. 2008;102:793-800. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Whang PG, Grauer JN. Infections of the spine. In: AAOS Comprehensive Orthopaedic Review 2. Elsevier. 2018;1:819-826. |

| 4. | Saha I, Paul B. Private sector involvement envisaged in the National Strategic Plan for Tuberculosis Elimination 2017–2025: Can Tuberculosis Health Action Learning Initiative model act as a road map? Med J Armed Forces India. 2019;75:25-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Moon MS. Tuberculosis of spine: Current views in diagnosis and management. Asian Spine J. 2014;8:97-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Berbudi A, Rahmadika N, Tjahjadi AI, Ruslami R. Type 2 Diabetes and its Impact on the Immune System. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2020;16:442-449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 241] [Cited by in RCA: 511] [Article Influence: 102.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Moin Uddin M, Sultana N, Rehan R, Khan AA. Pott’s Disease with Psoas Abscess in a Diabetic Patient: A Conservative Approach. Chattagram Maa-O-Shishu Hosp Med Coll J. 2014;13:67-69. |

| 8. | Ayberk G, Özveren MF, Yıldırım T. Spinal gas accumulation causing lumbar discogenic disease: a case report. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc. 2015;49:103-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Le Page L, Feydy A, Rillardon L, Dufour V, Le Hénanff A, Tubach F, Belmatoug N, Zarrouk V, Guigui P, Fantin B. Spinal tuberculosis: a longitudinal study with clinical, laboratory, and imaging outcomes. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2006;36:124-129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Marais S, Roos I, Mitha A, Mabusha SJ, Patel V, Bhigjee AI. Spinal Tuberculosis: Clinicoradiological Findings in 274 Patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;67:89-98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Cheung WY, Luk KDK. Clinical and radiological outcomes after conservative treatment of TB spondylitis: is the 15 years’ follow-up in the MRC study long enough? Eur Spine J. 2013;22:594-602. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lee KY. Comparison of Pyogenic Spondylitis and Tuberculous Spondylitis. Asian Spine J. 2014;8:216-223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Rajasekaran S, Soundararajan DCR, Shetty AP, Kanna RM. Spinal Tuberculosis: Current Concepts. Glob Spine J. 2018;8:96S-108S. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 23.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ismiarto AF, Tiksnadi B, Soenggono A. Young to Middle-Aged Adults and Low Education: Risk Factors of Spondylitis Tuberculosis with Neurological Deficit and Deformity at Dr. Hasan Sadikin General Hospital. Althea Med J. 2018;5:69-76. |

| 15. | Rajasekaran S, Kanna RM, Shetty AP. Pathophysiology and Treatment of Spinal Tuberculosis. JBJS Rev. 2014;2:e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ciang NC, Chan SCW, Lau CS, Chiu ETF, Chung HY. Risk of tuberculosis in patients with spondyloarthritis: data from a centralized electronic database in Hong Kong. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2020;21:832. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Han X, Wang Q, Wang Y. The impact of diabetes on tuberculosis treatment outcomes: evidence based on a cumulative meta-analysis. Int J Diabetes Dev Ctries. 2016;36:490-507. |

| 18. | Mukarram Siddiqui A. Clinical Manifestations and Outcome of Tuberculosis in Diabetic Patients Admitted to King Abdulaziz University Hospital in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. J Taibah Univ Med Sci. 4:148-155. |

| 19. | Novita BD, Ali M, Pranoto A, Soediono EI, Mertaniasih NM. Metformin induced autophagy in diabetes mellitus – Tuberculosis co-infection patients: A case study. Indian J Tuberc. 2019;66:64-69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Davidson SM, Duchen MR. Effects of NO on mitochondrial function in cardiomyocytes: Pathophysiological relevance. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;71:10-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Biondi B, Kahaly GJ, Robertson RP. Thyroid Dysfunction and Diabetes Mellitus: Two Closely Associated Disorders. Endocr Rev. 2019;40:789-824. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 293] [Article Influence: 48.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Cheung YM, Van K, Lan L, Barmanray R, Qian SY, Shi WY, Wong JLA, Hamblin PS, Colman PG, Topliss DJ, Denholm JT, Grossmann M. Hypothyroidism associated with therapy for multi-drug-resistant tuberculosis in Australia. Intern Med J. 2019;49:364-372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |