Published online Jul 26, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i21.7438

Peer-review started: October 7, 2021

First decision: March 3, 2022

Revised: March 30, 2022

Accepted: June 4, 2022

Article in press: June 4, 2022

Published online: July 26, 2022

Processing time: 276 Days and 19.9 Hours

Deep Sylvian meningiomas are rare and difficult to diagnose when small tumours lead to various symptoms. The difficulty associated with surgery is underestimated. Our case involved a mass (11 mm × 12 mm × 12 mm in size) in the right Sylvian fissure. It is the smallest deep Sylvian meningioma known and might be more easily misdiagnosed than previous examples.

A well-enhanced mass in the right Sylvian fissure of a 26-year-old male with a three-month history of seizure was identified via magnetic resonance imaging. The patient underwent operations twice for seizure control. During the first operation, the tumour was surrounded by the second segment of the middle cerebral artery and its numerous perforators. Partial resection had to be selected due to mild arterial damage. After the first operation, the patient presented with simple partial seizure. During reoperation, we isolated the anatomical structure near the tumour and the tumour over and removed it from its dorsal side by piecemeal resection.

This case reported the smallest deep Sylvian meningioma according to a literature review. Preoperative diagnosis is a crucial step due to deep Sylvian meningioma firmly adhering to the middle cerebral artery and its perforators. Adequate preparation is crucial to ensure the success of surgery.

Core Tip: This case reported the smallest deep Sylvian meningioma according to literature review. Preoperative diagnosis is a crucial step due to deep Sylvian meningioma firmly adhering to the middle cerebral artery and its perforators. Then, adequate preparation is the crucial point to ensure the success of surgery.

- Citation: Wang A, Zhang X, Sun KK, Li C, Song ZM, Sun T, Wang F. Deep Sylvian fissure meningiomas: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(21): 7438-7444

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i21/7438.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i21.7438

Meningiomas are neoplasms of the central nervous system and stem from arachnoid cap cells. It is rare for them to originate from a Sylvian fissure or the Virchow-Robin space of middle cerebral artery (MCA) and its branches[1]. Therefore, they might easily be misdiagnosed before surgical operations. Since 1938, 40 cases of deep Sylvian fissure meningiomas have been reported[2,3]. Here, we describe the case of a 26-year-old man with the smallest deep Sylvian fissure meningioma and review the associated literature.

A 26-year-old male had a three-month history of seizures.

A 26-year-old male had a three-month history of seizures developed intermittent abdominal discomfort followed by throat constriction, which spread from spells of numbness (from scalp to limb), lip smacking, and then severe seizures, with athetosis of the left upper limb and loss of consciousness. These symptoms persisted for only for four to five minutes; sometimes, symptoms of severe seizures occurred 4-5 times a day.

The patient was physically healthy and had no abnormal medical history.

No abnormalities.

The patient had no neurological deficits or physical abnormalities.

No abnormalities.

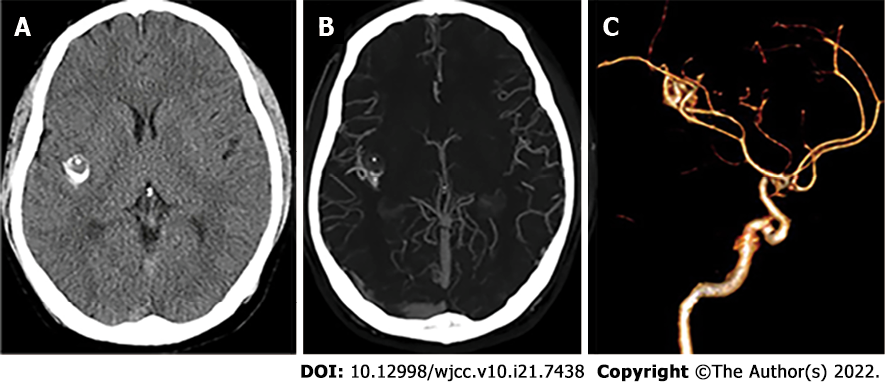

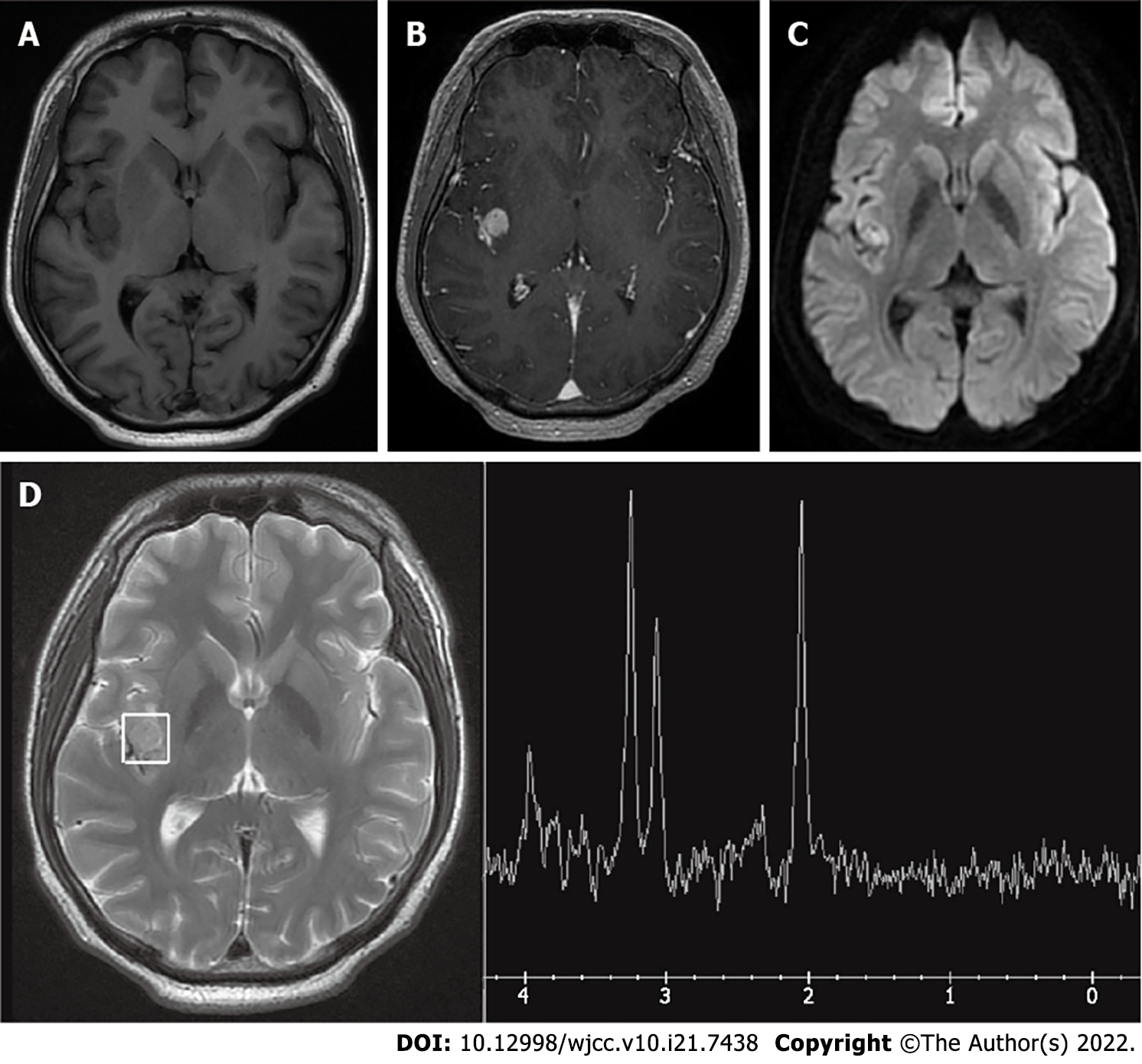

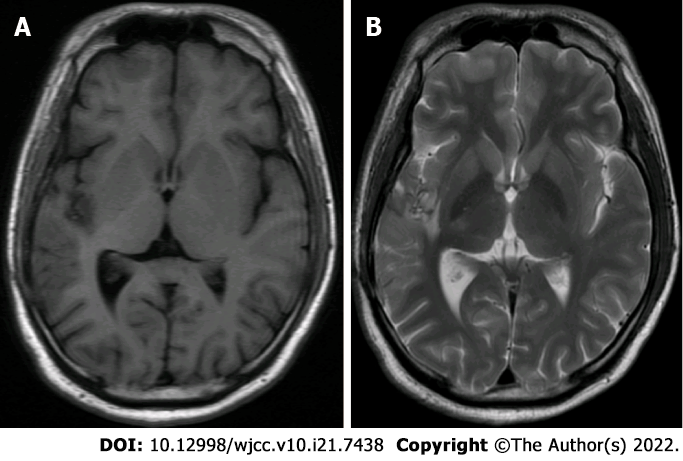

Computed tomography (CT) demonstrated a small calcified-like mass in the right temporal lobe adjacent to the Sylvian fissure. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a mass (11 mm × 12 mm × 12 mm) in the right insula without any dural attachment; the mass was primarily hypointense on T1 and hyperintense on the T2-weighted image, with satisfactory enhancement by contrast medium. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) showed a lower peak of N-acetyl-L-aspartic acid (NAA). The peaks of choline and creatine showed no significant change. Computed tomographic angiography (CTA) did not show any tumour stain or dilatation of the MCA (Figures 1 and 2).

The patient was diagnosed with psammomatous meningioma (World Health Organization grade I).

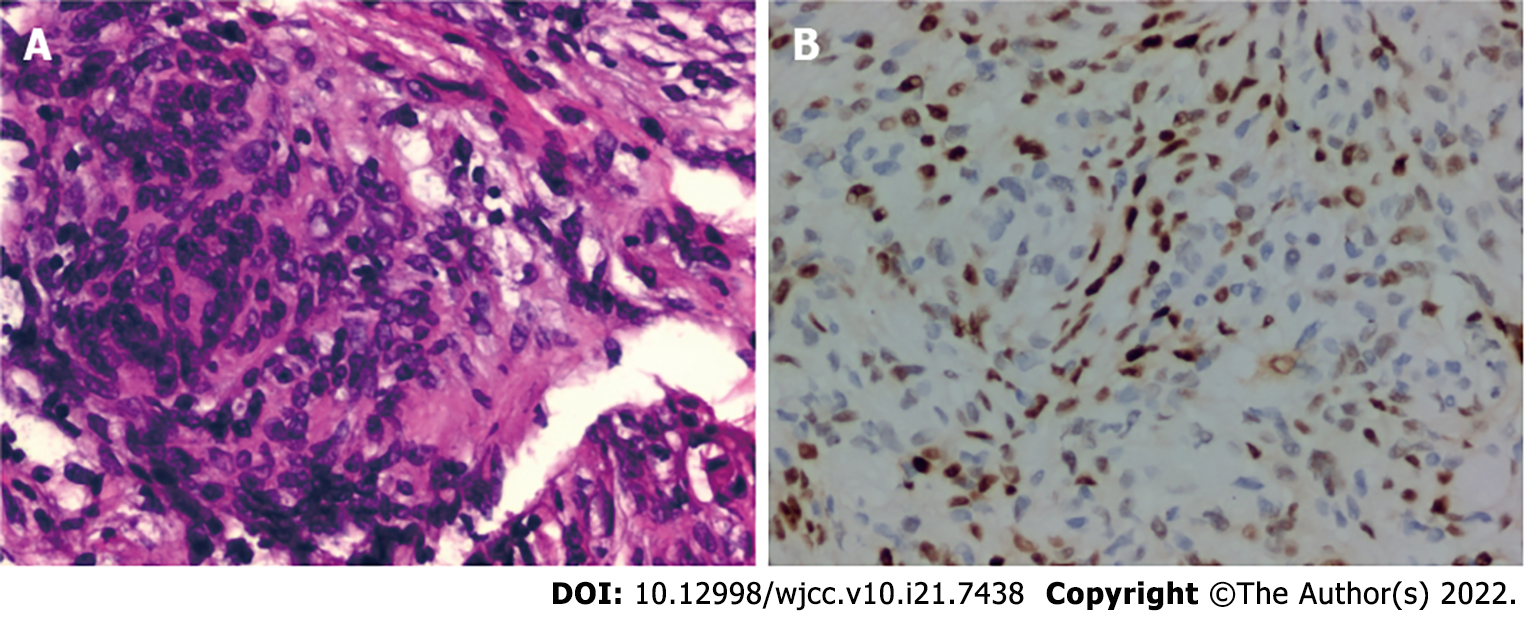

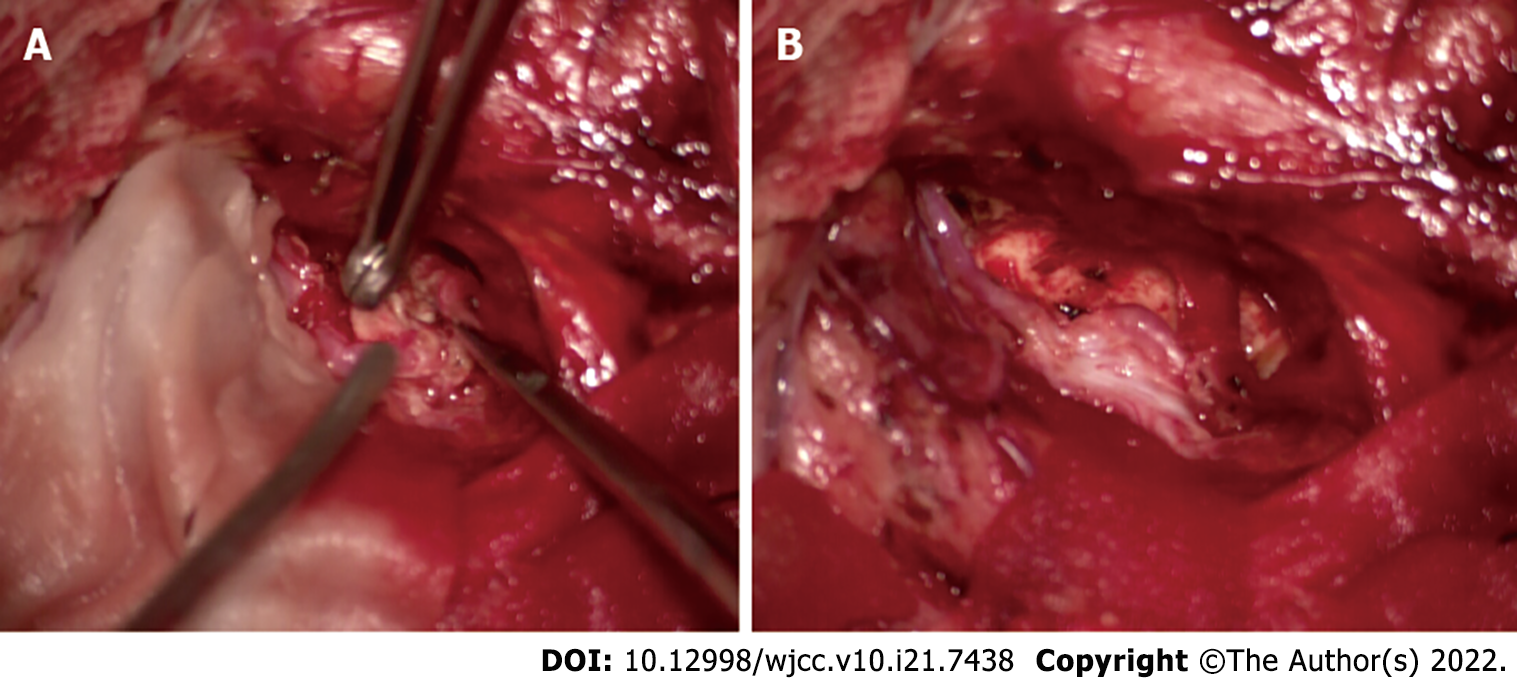

An insular lesion, angioreticuloma, or cavernous haemangioma was suspected. Right frontotemporal craniotomy and excision of the tumour were planned. The tumour was located deep in the lateral fissure, which is the surface of the insular cortex. It was closely attached to M2 segment of the MCA and its numerous perforators. Gravel-like particles were present on the surface of the tumour. Although we carefully isolated the tumor, unfortunately, a perforator artery was damaged, and the amount of blood loss was approximately 700 mL. To protect the main trunk of the MCA, we had to perform final partial resection of the mass. Histopathology and immunohistochemistry of the mass revealed a psammomatous meningioma (World Health Organization grade I) (Figure 3).

On the second day after the operation, the patient began to develop anomic aphasia and weakness in his left limb, which lasted for nearly two weeks. He gradually recovered after vasodilation therapy. After the operation, the seizures were significantly reduced, but the patient still occasionally presented with them (once a month). Along with the seizures, intermittent dizziness and vomiting occurred, followed by left limb numbness without loss of consciousness.

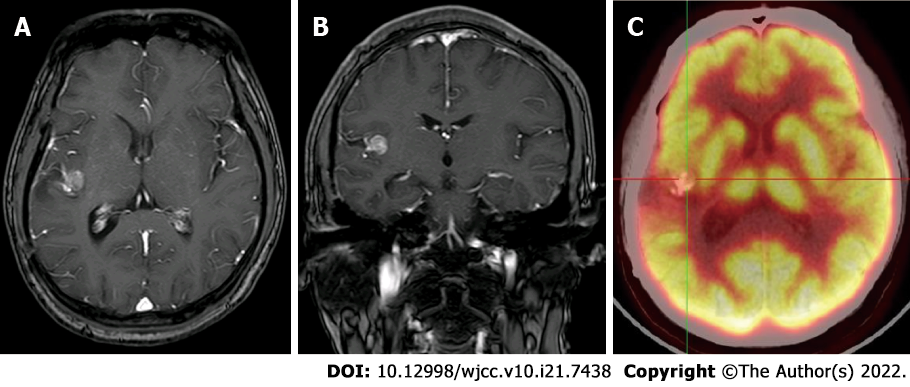

Considering the lack of seizure freedom and his young age, surgical resection was planned again a year after the initial surgery. MRI was performed again, and a small tumour was shown to be stable in the left Sylvian fissure. Positron emission tomography-computed tomographic (PET-CT) demonstrated the low metabolic area around the tumour and relatively limited surgical access (Figure 4). During reoperation, the opercular and MCA with its branch were exposed in the primary incision. After dissecting the Sylvian fissure, the tumor was found in the insular lobe, which was bared after separating the vascular structure of the insular surface. Then, we separated the tumour carefully from the insular lobe and MCA and removed it thoroughly by piecemeal resection. It was observed that the tumour originated from the adventitia of the MCA with strong adhesion (Figure 5).

After the second surgery, the patient was seizure-free and presented no seizure recurrence for approximately a year. MRI showed no lesion in the right temporal lobe adjacent to the lateral fissure (Figure 6).

The patient presented typical symptoms of insular epilepsy with a small tumour and atypical imaging characteristics[4,5]. Therefore, it was difficult to make the first and differential diagnoses. Thus, the difficulty of the operation was underestimated.

Meningiomas are the most common primary intracranial tumors. Their incidence is higher in middle-aged females[6,7]. Deep Sylvian meningioma is rare. Forty cases were reported from 1938 to 2021. We reviewed the papers and found that Sylvian meningiomas are mostly present in the children, with a male predominance, and sometimes in young men (Supplementary Table 1). Our case was a young man. The incidence in the age group of deep Sylvian meningioma was next to that in children. Similar to previous articles, histopathology and immunohistochemistry of the tumour revealed a psammomatous meningioma, which is the common pathological type of deep Sylvian meningioma.

Compared with other tumours, the level of evidence for the diagnosis and treatment of meningiomas is low. The preoperative diagnosis of meningioma is limited and often depends on MRI. CT plays an important role in the diagnosis of meningioma by detecting calcium in tumors. Our patient’s CT showed partial calcification, but MRI demonstrated homogenous enhancement and the absence of peritumoral oedema. In particularly, MRS revealed a low peak of NAA. All these findings made it difficult to support the diagnosis of meningiomas. The EEG in this case suggested that abnormal discharge was located on the left side, which was not consistent with seizures, considering the mirror effect. Intermittent and ictal scalp EEG changes might be variable and misleading due to the location of the insula in the deep area of the brain. Furthermore, the mass was so small that the region of interest contained brain tissue. All these findings led to the misdiagnosis.

Our case presented typical insular epilepsy symptoms, such as throat constriction, perioral and hemisensory symptoms, and then unilateral motor symptoms, thereby indicating that the lesion was in the posterior insula[8]. To our knowledge, the tumour of our patient is the smallest among those previously reported (Supplementary Table 1). However, the tumour was located on the insula and perisylvian, and the seizures were relieved after the first operation and disappeared after complete tumour resection in the second operation, which indicated that the location of the tumour in the brain was very important regardless of tumor size. Intermittent and ictal scalp EEG changes might be variable and misleading due to the location of the insula deep in the brain. Therefore, young adults and children with typical insular epilepsy symptoms combined with atypical imaging characteristics can have deep Sylvian meningioma.

The level of difficulty of surgery increased because of the origin and location of the deep Sylvian meningioma. We had to separate the tumour carefully from the MCA and then remove it by piecemeal resection in the second operation. Before the first operation, we suspected the lesion was angioreticuloma or cavernous haemangioma, which led to underestimation the difficulty of surgery. Because of the tight connection of deep Sylvian meningioma and MCA, precise microsurgery skills and perfect surgical plans, are important for the success of the operation.

Deep Sylvian meningiomas that originate from the MCA and its branches are rare. They can easily be misdiagnosed. The origin and location of deep Sylvian meningioma increase the difficulty of surgery. This study reported the smallest tumour with typical insular seizures and an atypical radiological examination of deep Sylvian meningiomas. Accurate diagnosis and adequate preoperative preparation are key to successful treatment.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Surgery

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Jugovic D, Germany; Vahedi P, Iran A-Editor: Liu X, China S-Editor: Wu YXJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wu YXJ

| 1. | Cai C, Zhu Z, Guo X, Jiang H, Zheng Z, Zhang J, Shao A, Zhu J. Sylvian Fissure Meningiomas: Case Report and Literature Review. Front Oncol. 2020;10:427. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 2. | Cushing H, Eisenhardt L. Meningiomas: their classification, regional behavior, life history and surgical end results. Charles C Thomas. City. 1938;. |

| 3. | Shrivastava RK, Segal S, Camins MB, Sen C, Post KD. Harvey Cushing's Meningiomas text and the historical origin of resectability criteria for the anterior one third of the superior sagittal sinus. J Neurosurg. 2003;99:787-791. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Jobst BC, Gonzalez-Martinez J, Isnard J, Kahane P, Lacuey N, Lahtoo SD, Nguyen DK, Wu C, Lado F. The Insula and Its Epilepsies. Epilepsy Curr. 2019;19:11-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Nieuwenhuys R. The insular cortex: a review. Prog Brain Res. 2012;195:123-163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 360] [Cited by in RCA: 404] [Article Influence: 31.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Goldbrunner R, Minniti G, Preusser M, Jenkinson MD, Sallabanda K, Houdart E, von Deimling A, Stavrinou P, Lefranc F, Lund-Johansen M, Moyal EC, Brandsma D, Henriksson R, Soffietti R, Weller M. EANO guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of meningiomas. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:e383-e391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 462] [Cited by in RCA: 577] [Article Influence: 64.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ostrom QT, Cioffi G, Gittleman H, Patil N, Waite K, Kruchko C, Barnholtz-Sloan JS. CBTRUS Statistical Report: Primary Brain and Other Central Nervous System Tumors Diagnosed in the United States in 2012-2016. Neuro Oncol. 2019;21:v1-v100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1108] [Cited by in RCA: 1776] [Article Influence: 355.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Mazzola L, Mauguière F, Isnard J. Functional mapping of the human insula: Data from electrical stimulations. Rev Neurol (Paris). 2019;175:150-156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |