Published online Jul 16, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i20.7124

Peer-review started: January 5, 2022

First decision: March 9, 2022

Revised: March 21, 2022

Accepted: May 22, 2022

Article in press: May 22, 2022

Published online: July 16, 2022

Processing time: 180 Days and 20 Hours

Immune checkpoint inhibitors have significantly improved survivals for an increasing range of malignancies but at the cost of several immune-related adverse events, the management of which can be challenging due to its mimicry of other autoimmune related disorders such as immunoglobulin G4 (IgG4) related disease when the pancreaticobiliary system is affected. Nivolumab, an IgG4 monoclonal antibody, has been associated with cholangitis and pancreatitis, however its association with IgG4 related disease has not been reported to date.

We present a case of immune-related pancreatitis and cholangiopathy in a patient who completed treatment with nivolumab for anal squamous cell carcinoma. Patients IgG4 levels was normal on presentation. She responded to steroids but due to concerns for malignant biliary stricture, she opted for surgery, the pathology of which suggested IgG4 related disease.

We hypothesize this case of IgG4 related cholangitis and pancreatitis was likely triggered by nivolumab.

Core Tip: Although immune checkpoint inhibitors are a game changer in the management of several cancers, they have been associated with immune related side effects due to their basic mechanism of immune hyperactivity. We hypothesize in our case report that nivolumab resulted in the overt expression of immunoglobulin G4 (IgG4) related pancreatitis and cholangitis. To our knowledge, this is the first report that documents a possible association between immune related side effects and IgG4 related disease.

- Citation: Agrawal R, Guzman G, Karimi S, Giulianotti PC, Lora AJM, Jain S, Khan M, Boulay BR, Chen Y. Immunoglobulin G4 associated autoimmune cholangitis and pancreatitis following the administration of nivolumab: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(20): 7124-7129

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i20/7124.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i20.7124

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICPi) have enabled tremendous survival improvements for an increasing range of malignancies[1]. These medications enhance immune activity against tumor cells by blocking down regulators of the immune system. However, normal cells may suffer collateral damage causing a host of inflammatory disorders. These have been referred to as immune-related adverse events (irAEs), the management of which can be challenging due to their varied and delayed manifestations[2-4]. Although the gastrointestinal tract, endocrine glands and skin are the most affected organs, there is growing evidence that demonstrate other organs such as bile ducts and pancreas can also be affected[4,5]. It can be challenging to differentiate immunoglobulin G4 (IgG4) related pancreaticobiliary conditions from irAEs which share a similar pathophysiology of immune hyperactivity[6,7].

We present a case of immune-related pancreatitis and cholangiopathy, which is either a rare manifestation of ICPi, or perhaps ICPi mediated overt expression of IgG4 related disease.

A 48-year-old female presents with two weeks of painless jaundice eight weeks after her last dose of nivolumab.

Along with painless jaundice, she also had generalized pruritus, dark urine, and pale-colored stool. She denied fever, chills, or any other relevant symptoms.

She had a history of well-controlled human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and asthma. She had presented with constipation, hematochezia, and an associated prolapsing anal mass a few months prior to current presentation. Excisional biopsy of the anal mass confirmed the diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). The patient completed Nigro protocol chemotherapy along with 27 fractions of radiation which was followed by 6 cycles of nivolumab.

She was an ex-smoker who had quit around 10 years ago. She had no notable family history.

Physical examination revealed jaundice with no other significant findings.

Serum total bilirubin was 9.2 mg/dL with direct fraction of 5.8 gm/dL, Alkaline phosphatase of 442 U/L, aspartate aminotransferase/alanine aminotransferase of 63 U/L and 144 U/L, and lipase 65 U/L. Her serum glucose was 447 mg/dL with an HbA1c of 8.2%. Carcinoembryonic antigen was 3.5 ng/mL and CA-19.9 was 5 U/mL. Serologic evaluation for viral, autoimmune, and hereditary causes of transaminitis was unremarkable. IgG4 level was normal at 108 gm/dL.

Computed tomography of the abdomen demonstrated fullness of the pancreatic head with new extrahepatic and intrahepatic biliary dilation. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) was performed, revealing diffuse hypoechoic changes, atrophy and lobularity affecting the pancreas diffusely, with peripancreatic lymphadenopathy. EUS-guided fine needle biopsy (FNB) of the pancreatic head revealed pancreatic acinar tissue with eosinophils and germinal center lymphoid aggregates. Features of malignancy were absent in pancreatic parenchymal and lymph node specimens as well as biliary brushings. A single localized biliary stricture was found within the distal common bile duct with upstream dilation which was relieved by a plastic biliary stent via endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (Figure 1). Overall, the findings in these specimens were suggestive of acute pancreatitis, which was attributed to recent nivolumab. The patient’s total bilirubin improved to normal levels with resolution of symptoms after biliary decompression with the plastic stent. She underwent repeat EUS which had similar findings with repeat sampling by FNB only suggestive of pancreatic inflammation. Bile duct forceps biopsy of the stricture indicated features of acute and chronic inflammation and granulation tissue with no malignancy.

Pathology suggested IgG4 related autoimmune cholangitis which we think was possibly triggered by nivolumab.

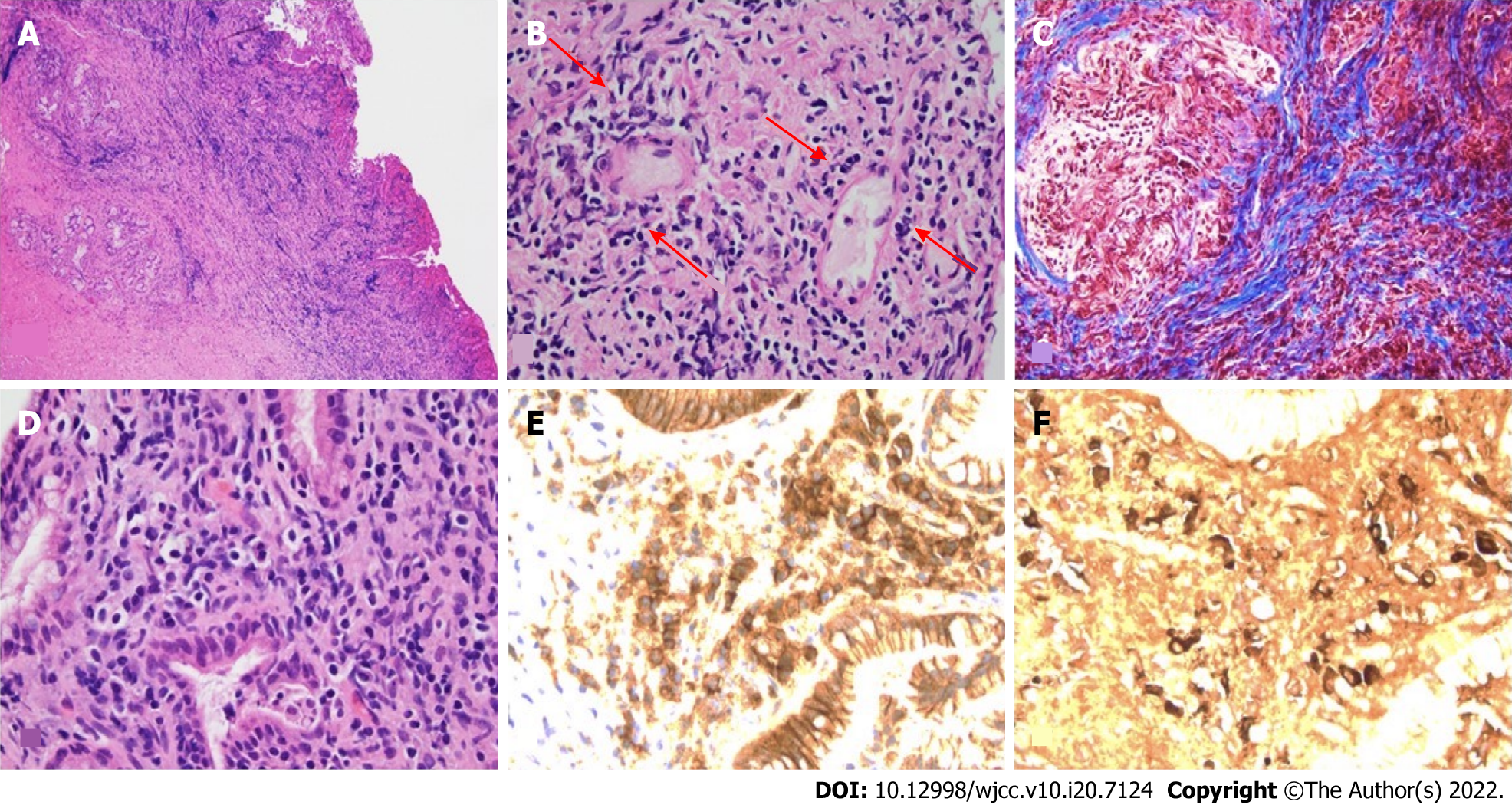

The persistent biliary stricture raised concerns for malignancy and also long term management of the stricture and therefore the patient elected to undergo surgical resection. A laparoscopic robotic cholecystectomy, resection of the extrahepatic bile duct and hepaticojejunostomy with a liver biopsy was performed. Liver biopsy revealed mild mixed macro-vesicular steatosis suggestive of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. The gallbladder had features of chronic cholecystitis with cholesterolosis and sections of the biliary mucosa in the common bile duct revealed marked mixed lymphoplasmacytic cell infiltrates, storiform fibrosis, lymphocytic phlebitis and IgG4 predominant plasmocytic cell infiltrates (30/HPF) (Figure 2).

Following the hepaticojejunostomy, the patient’s liver enzymes remained normal, and her diabetes progressively improved over several months. She no longer required insulin 3 mo after her surgery and her HgbA1C returned to 6%, which was her baseline prior to her diagnosis of anal SCC. Her anal SCC has remained in remission.

We report a diagnostically challenging case of cholangiopathy and pancreatitis in a patient with anal SCC treated with chemotherapy and radiation, followed by nivolumab. After the completion of ICPi immunotherapy, she presented with biliary obstruction and pancreatic inflammation raising concerns for an inflammatory vs neoplastic process. Multiple biopsies were inconclusive but were suggestive of a benign inflammatory process such as autoimmune pancreatitis. A trial of systemic steroid was considered but ultimately not pursued given her history of HIV and fear for reactivation. Her normal CD4 counts with undetectable viral load for HIV, made HIV a less likely etiology. Despite the normal serum IgG4 level and multiple cytologic specimens obtained by FNB, her diagnosis became clearer only after surgical excision which revealed an IgG4-mediated inflammatory process. ICPi exert their action by enhancing the immune response which lead to our hypothesis that this immune hyperactivity triggered by nivolumab resulted in florid expression an autoimmune process associated with IgG4 disease[2-4].

Nivolumab is not commonly associated with either pancreatitis or cholangitis. There is a 0%-4.5% and 0.5%-1.6% risk of hepatobiliary disease and pancreatitis with programmed cell death protein 1 therapy respectively[8]. Past research has shown that asymptomatic elevations in lipase and amylase are common with no significant increase in risk of any grade of pancreatitis with these mediations when used alone or in combination[8]. Symptomatic pancreatitis has only rarely been reported and has been treated by holding the medications and using steroids, ultimately resulting in improvement[9,10]. Cholangitis associated with ICPi has been described in two forms[1], large duct cholangitis or secondary sclerosing cholangitis where dilation and hypertrophy of extrahepatic bile ducts are seen on imaging[2] and small duct cholangitis, where there is pathologic evidence of bile duct involvement while larger ducts may appear normal on imaging. Based on limited data, large duct involvement is seen in up to 0.7% while the incidence of small duct involvement is unclear as it relies on liver biopsy[11]. In small duct cholangitis, the inflammatory infiltrate consists of predominantly CD8+ T cell infiltrates. In extrahepatic large ducts, there are plasma cell infiltrates, and the pathology may be very similar to IgG4 related cholangitis, though the density of IgG4 positive plasma cells are < 10/HPF[12,13].

On the other hand, pancreatitis and cholangitis are the most common gastrointestinal manifestations of chronic autoimmune fibroinflammatory IgG4 related disorders. Serum IgG4 levels are not specific or sensitive; histology provides the most reliable clue with the presence of lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates and IgG4 levels > 10 per HPF[6]. A cutoff of 50 IgG4 + cells per HPF is considered most reliable, however these are based on pancreatic specimens[14,15]. IgG4-related disease is rarely reported along with ICPi associated autoimmunity. Instead, it has been overlooked as serum IgG4 Levels are usually within normal limits. Among the several reports, only few cases had elevated serum IgG4[16,17]. Interestingly, while pembrolizumab and nivolumab are IgG4 monoclonal antibodies, durvalumab is an IgG1 monoclonal antibody, suggesting the fact that the observed autoimmune organ disease is not a result of direct toxicity by the monoclonal antibody[17].

Immunosuppression is the mainstay of therapy for most irAEs after discontinuing the offending agent[4]. Most toxicities are treated with glucocorticoids and responses are seen within 6-12 wk of therapy[18]. Poor responses despite prolonged immunosuppression with steroids have been reported in several case of sclerosing cholangitis which may be due to long half-life of nivolumab of up to 25 d[19]. Poor responses to mycophenolate and tacrolimus have also been reported[16]. Some benefit of ursodeoxycholic acid has also been seen[20].

We present a rare case of IgG4 related cholangitis and pancreatitis likely trigged by Nivolumab which has not been reported yet. Our hypothesis suggests a possible role of ICPi in the expression of an overt autoimmune process. More research is needed to study these associations which may help better evaluate and manage patients who are recipients of ICPi therapy.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Chen D, China; Ding X, China A-Editor: Lin FY, China S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: A P-Editor: Fan JR

| 1. | Bagchi S, Yuan R, Engleman EG. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors for the Treatment of Cancer: Clinical Impact and Mechanisms of Response and Resistance. Annu Rev Pathol. 2021;16:223-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 257] [Cited by in RCA: 1323] [Article Influence: 264.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ramos-Casals M, Brahmer JR, Callahan MK, Flores-Chávez A, Keegan N, Khamashta MA, Lambotte O, Mariette X, Prat A, Suárez-Almazor ME. Immune-related adverse events of checkpoint inhibitors. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2020;6:38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 399] [Cited by in RCA: 880] [Article Influence: 176.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Thanarajasingam U, Abdel-Wahab N. Immune Checkpoint Inhibition-Does It Cause Rheumatic Diseases? Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2020;46:587-603. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Postow MA, Sidlow R, Hellmann MD. Immune-Related Adverse Events Associated with Immune Checkpoint Blockade. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:158-168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2308] [Cited by in RCA: 3134] [Article Influence: 447.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Radulescu L, Crisan D, Grapa C, Radulescu D. Digestive Toxicities Secondary to Immune Checkpoint Inhibition Therapy - Reports of Rare Events. A Systematic Review. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2021;30:506-516. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Löhr JM, Vujasinovic M, Rosendahl J, Stone JH, Beuers U. IgG4-related diseases of the digestive tract. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;19:185-197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 18.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Gelsomino F, Vitale G, Ardizzoni A. Immune-mediated cholangitis: is it always nivolumab's fault? Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2018;67:1325-1327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Su Q, Zhang XC, Zhang CG, Hou YL, Yao YX, Cao BW. Risk of Immune-Related Pancreatitis in Patients with Solid Tumors Treated with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: Systematic Assessment with Meta-Analysis. J Immunol Res. 2018;2018:1027323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Dehghani L, Mikail N, Kramkimel N, Soyer P, Lebtahi R, Mallone R, Larger E. Autoimmune pancreatitis after nivolumab anti-programmed death receptor-1 treatment. Eur J Cancer. 2018;104:243-246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Yilmaz M, Baran A. Two different immune related adverse events occured at pancreas after nivolumab in an advanced RCC patient. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2022;28:255-258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Pi B, Wang J, Tong Y, Yang Q, Lv F, Yu Y. Immune-related cholangitis induced by immune checkpoint inhibitors: a systematic review of clinical features and management. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;33:e858-e867. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Zen Y, Chen YY, Jeng YM, Tsai HW, Yeh MM. Immune-related adverse reactions in the hepatobiliary system: second-generation check-point inhibitors highlight diverse histological changes. Histopathology. 2020;76:470-480. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Zen Y, Yeh MM. Hepatotoxicity of immune checkpoint inhibitors: a histology study of seven cases in comparison with autoimmune hepatitis and idiosyncratic drug-induced liver injury. Mod Pathol. 2018;31:965-973. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 168] [Cited by in RCA: 207] [Article Influence: 29.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Deshpande V, Zen Y, Chan JK, Yi EE, Sato Y, Yoshino T, Klöppel G, Heathcote JG, Khosroshahi A, Ferry JA, Aalberse RC, Bloch DB, Brugge WR, Bateman AC, Carruthers MN, Chari ST, Cheuk W, Cornell LD, Fernandez-Del Castillo C, Forcione DG, Hamilos DL, Kamisawa T, Kasashima S, Kawa S, Kawano M, Lauwers GY, Masaki Y, Nakanuma Y, Notohara K, Okazaki K, Ryu JK, Saeki T, Sahani DV, Smyrk TC, Stone JR, Takahira M, Webster GJ, Yamamoto M, Zamboni G, Umehara H, Stone JH. Consensus statement on the pathology of IgG4-related disease. Mod Pathol. 2012;25:1181-1192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1714] [Cited by in RCA: 1768] [Article Influence: 136.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Zamboni G, Lüttges J, Capelli P, Frulloni L, Cavallini G, Pederzoli P, Leins A, Longnecker D, Klöppel G. Histopathological features of diagnostic and clinical relevance in autoimmune pancreatitis: a study on 53 resection specimens and 9 biopsy specimens. Virchows Arch. 2004;445:552-563. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 503] [Cited by in RCA: 440] [Article Influence: 21.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Onoyama T, Takeda Y, Yamashita T, Hamamoto W, Sakamoto Y, Koda H, Kawata S, Matsumoto K, Isomoto H. Programmed cell death-1 inhibitor-related sclerosing cholangitis: A systematic review. World J Gastroenterol. 2020;26:353-365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 17. | Terashima T, Iwami E, Shimada T, Kuroda A, Matsuzaki T, Nakajima T, Sasaki A, Eguchi K. IgG4-related pleural disease in a patient with pulmonary adenocarcinoma under durvalumab treatment: a case report. BMC Pulm Med. 2020;20:104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Haanen JBAG, Carbonnel F, Robert C, Kerr KM, Peters S, Larkin J, Jordan K; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Management of toxicities from immunotherapy: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:iv119-iv142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1607] [Cited by in RCA: 1500] [Article Influence: 187.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 19. | Hamoir C, de Vos M, Clinckart F, Nicaise G, Komuta M, Lanthier N. Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic: Nivolumab-related cholangiopathy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;33:1695. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Talbot S, MacLaren V, Lafferty H. Sclerosing cholangitis in a patient treated with nivolumab. BMJ Case Rep. 2021;14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |