Published online Jul 16, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i20.7105

Peer-review started: December 18, 2021

First decision: January 25, 2022

Revised: February 4, 2022

Accepted: May 27, 2022

Article in press: May 27, 2022

Published online: July 16, 2022

Processing time: 198 Days and 11.5 Hours

Lynch syndrome (LS) is an autosomal dominant hereditary disorder because of germline mutations in DNA mismatch repair genes, such as MutL homolog 1 (MLH1), PMS1 homolog 2, MutS homolog 2, and MutS homolog 6. Gene mutations could make individuals and their families more susceptible to experiencing various malignant tumors. In Chinese, MLH1 germline mutation c.(453+1_454-1)_(545+1_546-1)del-related LS has been infrequently reported. Therefore, we report a rare LS patient with colorectal and endometrioid adenocarcinoma and describe her pedigree characteristics.

A 57-year-old female patient complained of irregular postmenopausal vaginal bleeding for 6 mo. She was diagnosed with LS, colonic malignancy, endometrioid adenocarcinoma, secondary fallopian tube malignancy, and intermyometrial leiomyomas. Then, she was treated by abdominal hysterectomy, bilateral oviduct oophorectomy, and sentinel lymph node resection. Genetic testing was performed using next-generation sequencing technology to detect the causative genetic mutations. Moreover, all her family members were offered a free genetic test, but no one accepted it.

No tumor relapse or metastasis was found in the patient during the 30-mo follow-up period. The genetic panel sequencing showed a novel pathogenic germline mutation in MLH1, c.(453+1_454-1)_(545+1_546-1)del, for LS. Moreover, cancer genetic counseling and testing are still in the initial development state in China, and maybe face numerous challenges in the further.

Core Tip: Lynch syndrome (LS) is an autosomal dominant hereditary disorder because of germline mutations in DNA mismatch repair genes, such as MutL homolog 1 (MLH1) gene, PMS1 homolog 2 gene, MutS homolog 2 gene, and MutS homolog 6 gene, which make the patient more susceptible to other malignancies. In Chinese, MLH1 germline mutation c.(453+1_454-1)_(545+1_546-1)del-induced LS has been infrequently reported. In this paper, we report a rare LS patient with colorectal and endometrioid adenocarcinoma. The genetic panel sequencing showed a novel pathogenic germline mutation in MLH1, c.(453+1_454-1)_(545+1_546-1)del, for LS.

- Citation: Zhang XW, Jia ZH, Zhao LP, Wu YS, Cui MH, Jia Y, Xu TM. MutL homolog 1 germline mutation c.(453+1_454-1)_(545+1_546-1)del identified in lynch syndrome: A case report and review of literature. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(20): 7105-7115

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i20/7105.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i20.7105

Lynch syndrome (LS) is an autosomal dominant inherited disorder because of germline mutations in DNA mismatch repair (MMR) genes, such as MutL homolog 1 (MLH1), PMS1 homolog 2 (PMS2), MutS homolog 2 (MSH2), and MutS homolog 6 (MSH6), which make the patient more susceptible to other malignancies[1,2]. MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2 mutations in LS account for approximately 50%[3-5], 40%[5], 7%-20%[3-8], and < 6%[3,4,9] of all cases, respectively. Additionally, specific MMR gene deficiencies might result in different ages of onset, types of malignancy, and clinical signs[10]. The MLH1 gene defects could decrease the expression of MLH1 protein, affecting the MMR function, leading to errors in DNA replication and ultimately inducing neoplams[11,12].

LS can be classified as types I and II according to the location of tumors[3,13,14]. Type I is an intestinal neoplasm, such as colorectal cancer[14]. Besides, type II is defined as colorectal malignancy complicated with parenteral cancers, including gastric cancer[15], renal cell cancer[16], epithelial ovarian cancer[17], endometrial cancer[2], bladder cancer[18,19], breast cancer[20], and even repeated stroke[10]. Endometrial cancer is the most frequent parenteral tumor among LS patients[21,22], which ranks 3rd in the mortality of all gynecological cancers[23]. In recent years, LS-associated endometrial cancer (LSAEC) has received increasing attention in the medical field[24]. Furthermore, the offspring of LS patients will have a 50% incidence of inheritance[24]. More than 2600 mutations have been reported worldwide[10,24,25], but MLH1 exon 6 c.(453+1_454-1)_(545+1_546-1)del-induced LS has been rarely described in Chinese. Therefore, we present a rare case with an MLH1 germline mutation, analyze her pedigree characteristics, and review the MLH1 gene mutation loci.

A 57-year-old Chinese female patient complained of irregular postmenopausal vaginal bleeding. The demographic characteristics of the patient are listed in Table 1.

| Parameter | Outcome |

| Sex | Female |

| Age (yr) | 57 |

| Sample type | Peripheral venous blood |

| Genes | EPCAM, MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2, STK11, TP53, PTEN, MUTYH, BRCA1, MLH3 |

| Length of the target region (bp) | 49287 |

| Target area coverage | 100% |

| Average depth of target area (×) | 608.777386 |

| Average depth of target area > 30 × the proportion of sites | 99.78% |

| Detection range | Exon and its adjacent ± 20 bp intron region |

The patient had the clinical symptom of irregular vaginal bleeding for 6 mo.

The patient had a medical history of colon cancer and received a radical colon cancer operation 20 years ago.

The patient and many of her family members had a cancer history.

A small amount of white secretions with no odor was found in the vagina. A smooth cervical surface was detected. The vulva was atrophic, the vagina was patent, and mucosal fold atrophy was palpated. Moreover, the uterine was in an anterior position, with a smooth surface and good range of motion. No obvious abnormality was found in the bilateral adnexal areas.

No abnormality was found in the routine blood tests.

Preoperative abdominal Doppler ultrasound showed that the uterus, with a size of 3.8 cm × 3.5 cm × 3.1 cm, was located in an anterior position, the uterine cavity line was clear, the endometrial thickness was 1.1 cm (significantly greater than the normal value of endometrial thickness in postmenopausal women), and the ultrasonic echo of the endometrium was uneven. In addition, bilateral ovaries and adnexa presented no abnormality. Color Doppler flow imaging showed no abnormal blood flow signal.

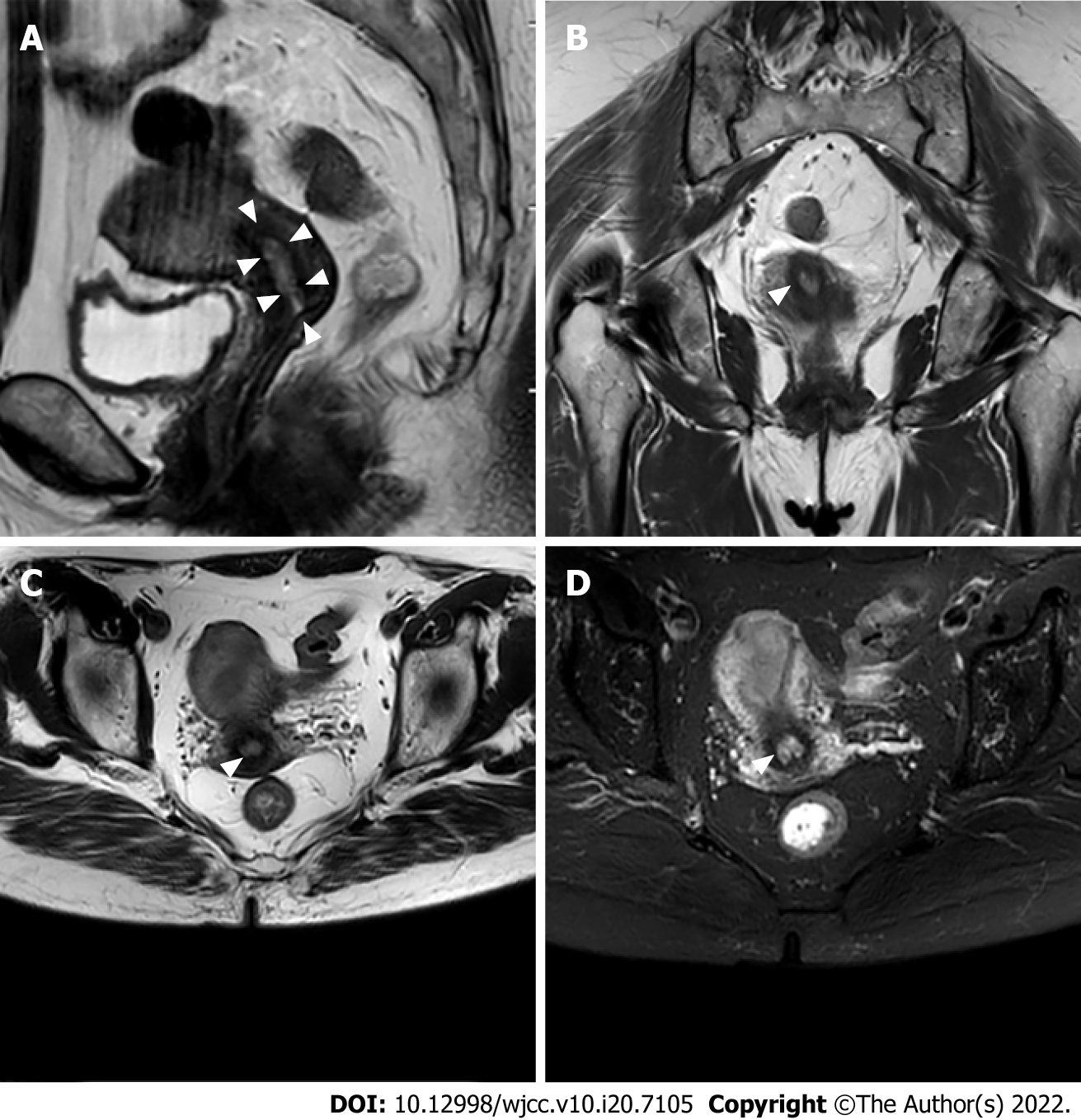

Abdominal magnetic resonance imaging showed that the uterus was in an anteversion and flexion position. A mass with an equal T1 and slightly long T2 signal was found in the uterine cavity, with an unclear boundary (Figure 1A). The tumor size was about 31 mm × 23 mm, and the display of the uterine junction was not clear (Figure 1B and C). The enhanced images showed that the lesions exhibited inhomogeneous enhancement. Diffusion-weighted imaging showed that the lesions exhibited a high signal. The shape and signal of the bilateral adnexa were normal (Figure 1D). There was no obvious abnormal signal in the bladder and rectum. No abnormality was found in bilateral iliac vessels and inguinal lymph nodes. No effusion was found in the pelvic cavity, and no obvious abnormal signal was found in pelvic wall soft tissue.

The clinical diagnosis was endometrioid adenocarcinoma (IIIA1) and LS.

After general anesthesia, abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral oviduct oophorectomy were performed. The whole uterus and bilateral appendages were examined during the operation by fast-frozen histopathology. It revealed a poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma of the uterus, which infiltrated the superficial muscularis. Subsequently, sentinel lymph node resection was also performed. After surgery, the patient was treated with regular chemotherapy for six courses, including paclitaxel (Nanjing Green Leaf Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Nanjing, China) and carboplatin injection (Qilu Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Jinan, China).

The biopsy histochemical (hematoxylin-eosin) staining showed that endometrial cancer was moderately to poorly differentiated. A few of its lesions were accompanied by squamous differentiation. The tumor infiltrated into the superficial muscle wall. Noticeably, one side of the fallopian tube showed cancerous lesions, while the other side of the fallopian tube and bilateral ovaries showed no cancerous lesions. However, cervical vessels, blood vessels, lymphatic vessels, and nerves were not invaded. Bilateral pelvic lymph nodes were normal.

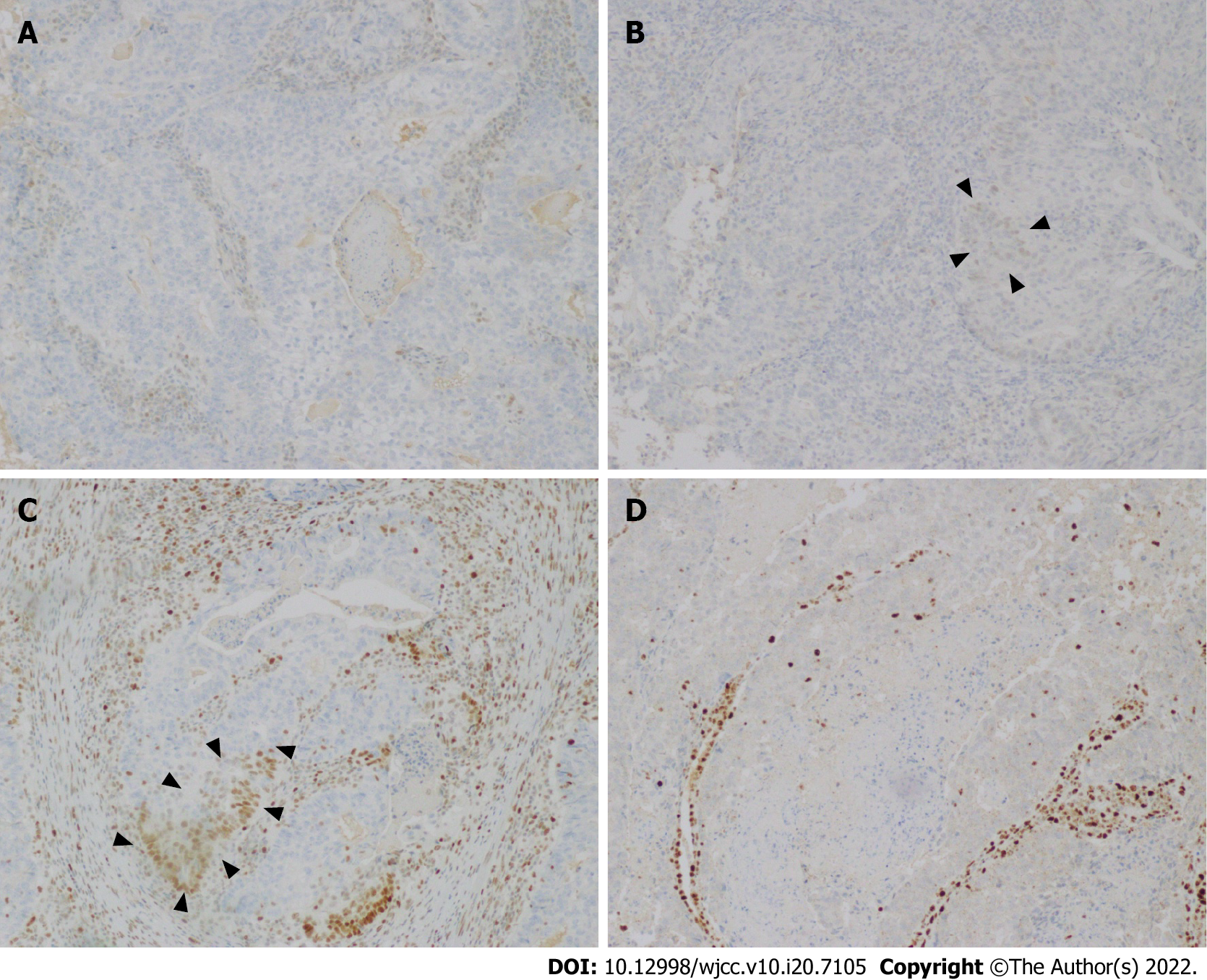

Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining results showed MLH1 (-), PMS2 (-), MSH6 (+-), MSH2 (+-), BRAF V600E mutation-specific antibody (VE1) (Ventana IHC enhanced amplification kit) (-), CD31 (-), D2-40 (-), CK5/6 (partial lesions +-), p63 (+-), and CDX2 (-) (Figure 2). Besides, the positive rate of PR was 90+ACU- (+-). The positive rate of ER was 90+ACU- (+-). The positive rate of Ki67 was 60+ACU-. P53 was scattered weak positive, and P16 was partially positive. Based on these findings, the patient was diagnosed with endometrioid adenocarcinoma (IIIA1).

No tumor recurrence or metastasis was found during a 2.5-year follow-up period. Computed tomography was performed after six chemotherapy courses and showed no abnormality in the head, liver, gallbladder, spleen, pancreas, bilateral kidney, bilateral ureter, rectum, or lung.

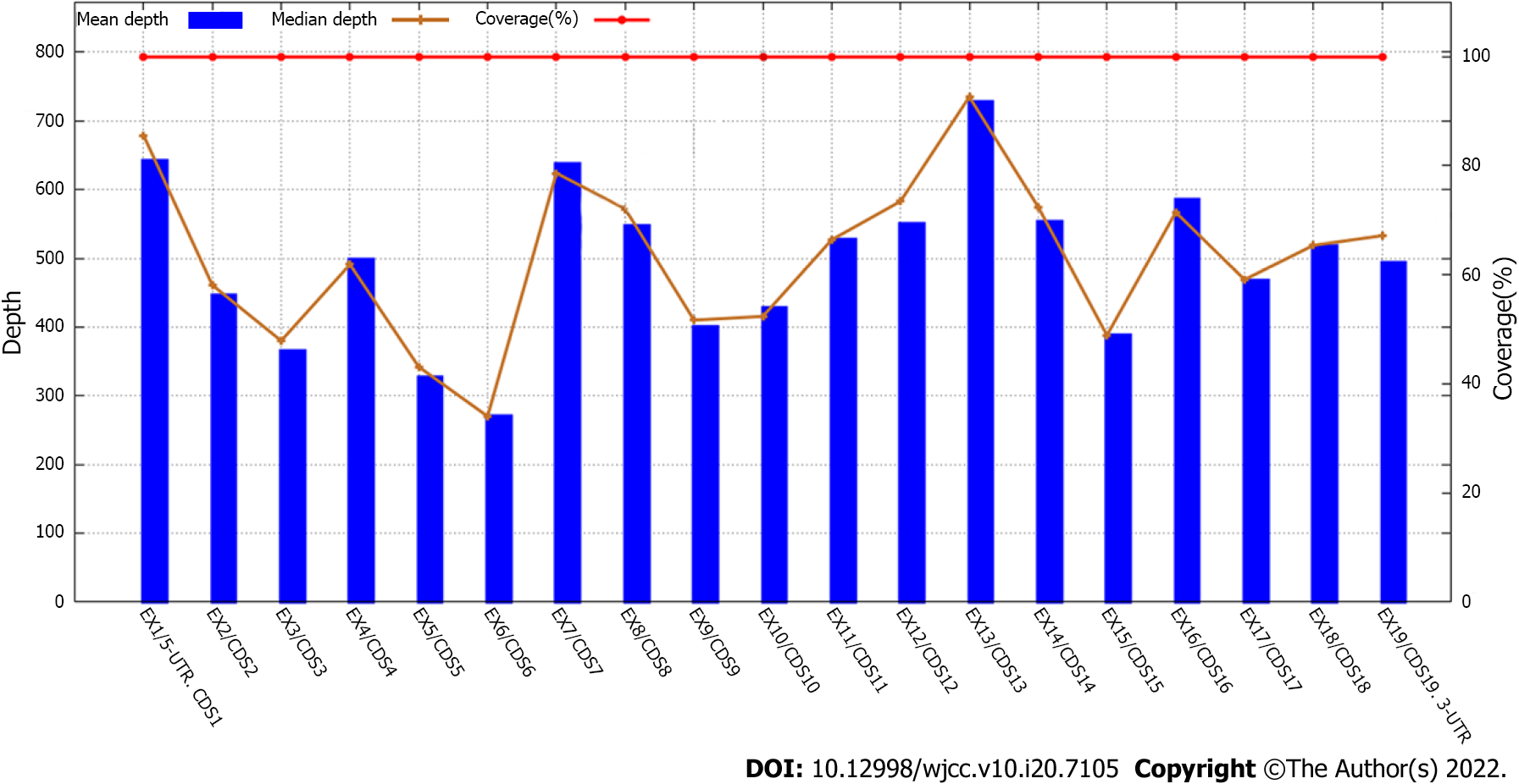

The results of gene sequencing are shown in Tables 2 and 3. A heterozygous deletion mutation of exon 6 was detected in the MLH1 gene, which was named c.(453+-1+AF8-454-1)+AF8-(545+-1+AF8-546-1)del according to the Human Genome Variation Society (Figure 3). Postoperatively, the patient was diagnosed with LS, endometrioid adenocarcinoma (IIIA1), colonic malignancy, secondary fallopian tube malignancy, and intermyometrial leiomyomas.

| Parameter | Outcome |

| Diagnosis | Hereditary EC |

| Gene (NM number) | MLH1 (NM_000249.3) |

| Nucleotide changes | Exon 6 del |

| Amino acid changes | - |

| Gene subregion | Exon 6 |

| Heterozygous | Heterozygous mutation |

| Functional changes | Deletion |

| Genetic model | AD |

| Gene mutation type | Known pathogenic mutation |

| No. | Gene | Transcript | NV | AAC | GS | Heterozygous | Rs NO. | FC | MT |

| 1 | MLH1 | NM_000249.3 | EX6 DEL | - | EX6 | Het | - | Deletion | Kv |

| 2 | MLH1 | NM_000249.3 | c.1151T>A | p.Val384Asp | CDS12 | Het | rs63750447 | Missense | Bp |

| 3 | MUTYH | NM_001128425.1 | c.74G>A | p.Gly25Asp | CDS2 | Het | rs75321043 | Missense | Uv |

| 4 | MUTYH | NM_001128425.1 | c.53C>T | p.Pro18Leu | CDS2 | Het | rs79777494 | Missense | Uv |

| 5 | MUTYH | NM_001128425.1 | c.36+11C>T | - | IN1 | Het | rs2275602 | Splice | Bp |

| 6 | MUTYH | NM_001128425.1 | c.1014G>C | p.Gln338His | CDS12 | Het | rs3219489 | Missense | Bp |

| 7 | BRCA1 | NM_007294.3 | c.2612C>T | p.Pro871Leu | CDS9 | Het | rs799917 | Missense | Bp |

| 8 | BRCA1 | NM_007294.3 | c.4837A>G | p.Ser1613Gly | CDS14 | Het | rs1799966 | Missense | Bp |

| 9 | BRCA1 | NM_007294.3 | c.3548A>G | p.Lys1183Arg | CDS9 | Het | rs16942 | Missense | Bp |

| 10 | BRCA1 | NM_007294.3 | c.3113A>G | p.Glu1038Gly | CDS9 | Het | rs16941 | Missense | Bp |

| 11 | EPCAM | NM_002354.2 | c.344T>C | p.Met115Thr | CDS3 | Het | rs1126497 | Missense | Bp |

| 12 | MLH3 | NM_014381.2 | c.2531C>T | p.Pro844Leu | CDS1 | Het | rs175080 | Missense | Bp |

| 13 | MLH3 | NM_014381.2 | c.2476A>G | p.Asn826Asp | CDS1 | Hom | rs175081 | Missense | Bp |

| 14 | MSH2 | NM_000251.2 | c.211+9C>G | - | IN1 | Het | rs2303426 | Splice | Bp |

| 15 | MSH6 | NM_000179.2 | c.3438+14A>C | - | IN5 | Hom | rs2020911 | Splice | Bp |

| 16 | PMS2 | NM_000535.6 | c.1408C>T | p.Pro470Ser | CDS11 | Het | rs1805321 | Missense | Bp |

| 17 | PMS2 | NM_000535.6 | c.2570G>C | p.Gly857Ala | CDS15 | Hom | rs1802683 | Missense | Bp |

| 18 | PMS2 | NM_000535.6 | c.706-4delT | - | IN6 | Het | rs6079473 | Splice | Bp |

| 19 | PMS2 | NM_000535.6 | c.59G>A | p.Arg20Gln | CDS2 | Het | rs10254120 | Missense | Bp |

| 20 | PMS2 | NM_000535.6 | c.1621A>G | p.Lys541Glu | CDS11 | Hom | rs2228006 | Missense | Bp |

| 21 | PMS2 | NM_000535.6 | c.705+17A>G | - | IN6 | Het | rs62456182 | Splice | Bp |

| 22 | PMS2 | NM_000535.6 | c.2007-4G>A | - | IN11 | Het | rs1805326 | Splice | Bp |

| 23 | PMS2 | NM_000535.6 | c.2007-7C>T | - | IN11 | Het | rs55954143 | Splice | Bp |

| 24 | PTEN | NM_000314.6 | c.802-3dupT | - | IN7 | Het | rs762344516 | Splice | Bp |

| 25 | TP53 | NM_000546.5 | c.215C>G | p.Pro72Arg | CDS3 | Het | rs1042522 | Missense | Bp |

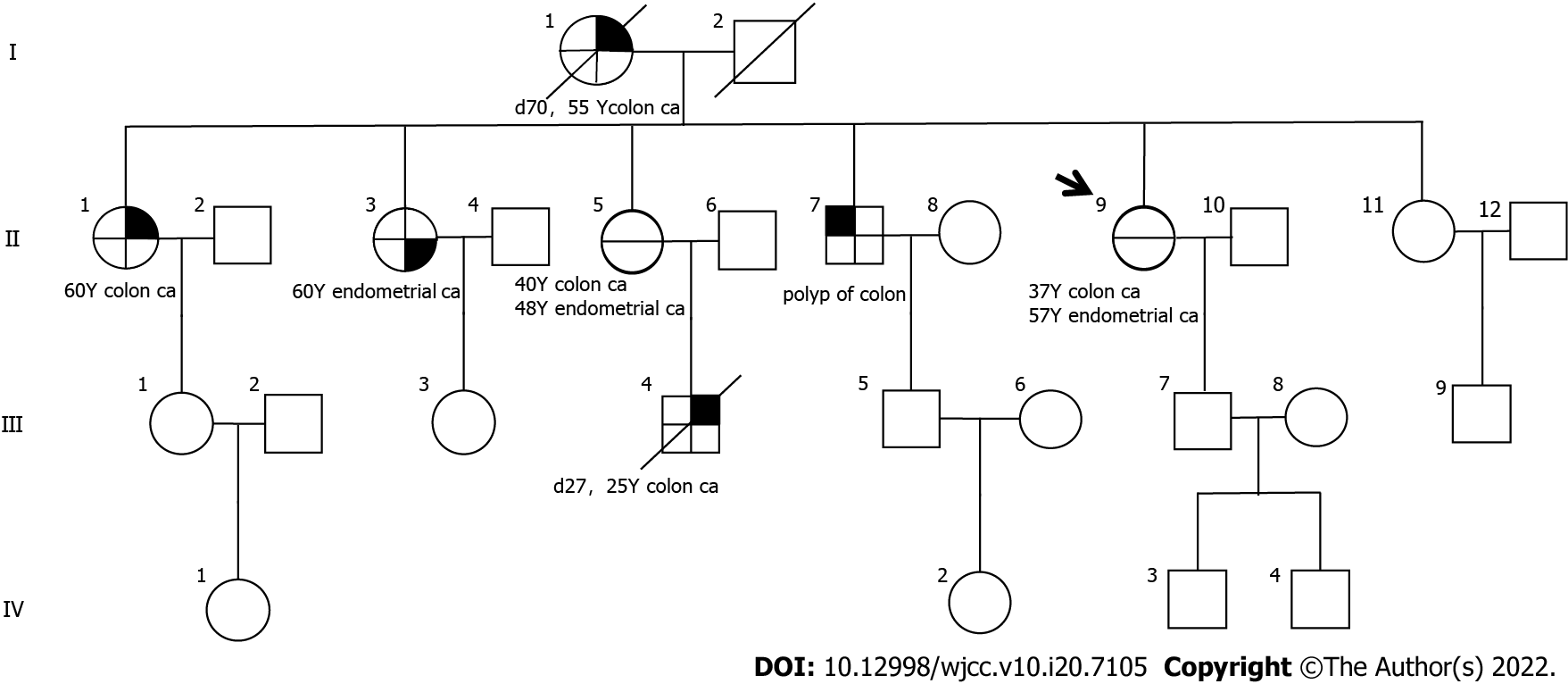

The patient’s eldest sister was diagnosed with colon cancer at age 60, the second sister with endometrial cancer at age 60, the third sister with colon cancer at age 40, the older brother with colon polyps three times between the ages of 40 and 50, the mother with endometrial cancer at age 48, and the mother with colon cancer at age 50. The prevalence spectrum of the four generations of patients is shown in Figure 4.

Genetic counseling was conducted among the family relatives. Moreover, we provided free Sanger mutation site verification tests for the family members of the patient. However, all relatives refused to be tested.

Colorectal cancer is the 5th commonly diagnosed cancer in China[23,26]. In 2015, the number of colorectal cancer-related deaths and new cases in China was approximately 191000 and 376300, respectively. Moreover, hereditary colorectal malignancy accounts for 5%-10% of colorectal malignancies, including LS, Li-Fraumeni syndrome, MUTYH-associated polyposis, juvenile polyposis syndrome, familial adenomatous polyposis, and Peutz-Jeghers syndrome[27]. In this study, the patient had a medical history of colon cancer 20 years ago and has experienced endometrial adenocarcinoma. We found that the patient carries a novel pathogenic genetic deletion mutation in MLH1. Many researchers have reported diseases caused by MLH1 gene mutations[28-31]. Hong et al[31] detected that the deletion of exon 7 to exon 19 of the MLH1 gene was a pathogenic mutation causing colorectal cancer. Jia et al[28] reported that the p.K618del variant in MLH1 was the causative pathogenic genetic variant for LS. Solassol et al[29] found that an AluY5a insertion in MLH1 exon 6 led to exon skipping, which resulted in a pathogenic frameshift in patients who developed colorectal adenocarcinomas. Li et al[30] reported that the insertion of a truncated AluSx like element into MLH1 intron 7 resulted in aberrant splicing and transcription, thus inducing LS. Lagerstedt-Robinson et al[32] reported an LS patient with the deletion of MLH1 c.(453+1_454-1)_(545+1_546-1) in Switzerland. However, in China, the MLH1genetic mutation c.(453+1_454-1)_(545+1_546-1) del has not been reported. Consequently, we present a relatively rare LS patient with MLH1 c.(453+1_454-1)_(545+1_546-1)del and describe the clinical features, pathological features, and familial morbidity of the proband.

The demographic characteristics of LSAEC are as follows: First, the pathological types are diverse and poorly differentiated. Second, the onset age is between 46 and 54 years old. Third, the majority of the pathological changes are situated in the lower segment of the corpus uteri[33]. The potential risk of LS patients experiencing another cancer at 10 and 15 years was 25% and 50%, respectively[34]. The present case had colon cancer at age 37. Twenty years later, she was diagnosed with endometrioid adenocarcinoma. The demographic characteristics of the present patient were similar to those reported in the previous studies[21,34].

Concerning the diagnosis of LS, Amsterdam II[35] and Bethesda[36] criteria have been widely used to screen for LS. In the present study, the patient met the criteria of the Amsterdam standard Ⅱ and the revision of the Bethesda guidelines. Nonetheless, the two standards’ sensitivity is low because they are based on clinical background and family history[37-39]. Thus, Amsterdam II and Bethesda criteria are inadequate as independent screening tools.

IHC was a useful method for LS screening[37,40,41], particularly in colorectal malignancy patients. The sensitivity and specificity of IHC in patients with MMR mutations are 83% and 89%, respectively[42]. When IHC results suggest deleting MLH1 and PMS2 proteins, universal screening including BRAF testing and MLH1 promoter methylation analysis is required[10,22,24,25,28,38-40,43,44]. In the present study, the IHC results showed the loss of MLH1 and PMS2 proteins, but expression of MSH2 and MSH6 proteins in the tumor cells. Subsequently, MLH1 mutation was considered. The patient had a medical history of colon cancer and a family history of LS-related cancers. Then, she was diagnosed with LS. Also, we advised the patient and her family members to receive genetic counseling.

Before genetic testing, we provided genetic counseling for the patient and obtained a clear LS family history. We found that the proband’s mother (I-1) suffered from primary colon cancer at 55 years and died at 70 years, two of her sisters [(II-1) and (II-3)] were affected by colon cancer at 60 years and endometrial cancer at 60 years, respectively, one of her sisters (II-5) experienced colon cancer at 40 years and endometrial cancer at 48 years, her brother (II-7) developed polyps of the colon, and her nephew developed colon cancer at 25 years and died at 27 years. Besides, standard processes of cancer-related genetic counseling should include pre-test counseling, results analysis, and follow-up[28]. In our study, the family history suggested the clinical diagnosis of LS. Then, the patient and family members were given detailed pre-test counseling. However, we cannot make a definitive diagnosis of LS without genetic testing[28]. Consequently, genetic testing was recommended for the proband and her relatives.

Furthermore, we provided free genetic tests for all her family members to help at-risk offspring know their risk of developing cancers, thus enabling them to access personalized precision medicine. Unexpectedly, only the proband received the genetic test, but her family members refused. The reasons for the relatives of the proband to refuse genetic testing are as follows: First, they were worried that their genetic problems may cause difficulties in mate selection or affect the stability of marriage. Second, they will be unable to purchase life insurance if they have a genetic defect. Third, they are worried about personal privacy exposure. Wang et al[45] investigated the willingness and awareness of genetic screening for patients undergoing colon cancer surgery at Peking Union Medical College Hospital who had any protein (MLH1/MLH2/MLH6/PMS2) expression deletion suggested by IHC, and the result indicated that 27.4% (61/219) of the patients explicitly refused to undergo genetic screening. The findings of our study and Wang et al[45] indicate that gynecologists should strengthen health education. Therefore, cancer genetic counseling and testing are still in the initial development stage in China, and maybe face numerous challenges in the further[28]. This dilemma is expected to be improved with better preventative education to the general population and a better understanding of cancer genetics among cancer patients and medical practitioners[28].

The patient achieved positive clinical outcomes during the 30-mo follow-up visit period. However, several limitations exist in this study. First, 6 mo after discharge, the proband’s 25-year-old offspring (III-4) was diagnosed with colon cancer and died at age 27. We believe that this unfortunate outcome could have been prevented if her family members had taken genetic testing and then received individualized preventive treatment before the malignant tumor onset. Thus, it is essential to enhance genetic testing awareness among the Chinese population, especially in rural areas.

MLH1 exon 6 c.(453+1_454-1)_(545+1_546-1)del mutation is a novel pathogenic mutation of LS in Chinese. This case report emphasizes the value of diagnosis and treatment in patients with inherited malignancy syndromes. To date, cancer genetic counseling and testing are still in the initial development state in China, and maybe face numerous challenges in the further.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Obstetrics and gynecology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Dabravolski SA, Belarus; Yoshida H, Japan A-Editor: Yao QG, China S-Editor: Chang KL L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Chang KL

| 1. | Kahn RM, Gordhandas S, Maddy BP, Baltich Nelson B, Askin G, Christos PJ, Caputo TA, Chapman-Davis E, Holcomb K, Frey MK. Universal endometrial cancer tumor typing: How much has immunohistochemistry, microsatellite instability, and MLH1 methylation improved the diagnosis of Lynch syndrome across the population? Cancer. 2019;125:3172-3183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ryan NAJ, Glaire MA, Blake D, Cabrera-Dandy M, Evans DG, Crosbie EJ. The proportion of endometrial cancers associated with Lynch syndrome: a systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. Genet Med. 2019;21:2167-2180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 25.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Bhattacharya P, McHugh TW. Lynch Syndrome. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL), 2019. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 4. | Borràs E, Pineda M, Cadiñanos J, Del Valle J, Brieger A, Hinrichsen I, Cabanillas R, Navarro M, Brunet J, Sanjuan X, Musulen E, van der Klift H, Lázaro C, Plotz G, Blanco I, Capellá G. Refining the role of PMS2 in Lynch syndrome: germline mutational analysis improved by comprehensive assessment of variants. J Med Genet. 2013;50:552-563. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Peltomäki P. Role of DNA mismatch repair defects in the pathogenesis of human cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1174-1179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 508] [Cited by in RCA: 509] [Article Influence: 23.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Miyaki M, Konishi M, Tanaka K, Kikuchi-Yanoshita R, Muraoka M, Yasuno M, Igari T, Koike M, Chiba M, Mori T. Germline mutation of MSH6 as the cause of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. Nat Genet. 1997;17:271-272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 460] [Cited by in RCA: 431] [Article Influence: 15.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Berends MJ, Wu Y, Sijmons RH, Mensink RG, van der Sluis T, Hordijk-Hos JM, de Vries EG, Hollema H, Karrenbeld A, Buys CH, van der Zee AG, Hofstra RM, Kleibeuker JH. Molecular and clinical characteristics of MSH6 variants: an analysis of 25 index carriers of a germline variant. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;70:26-37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 218] [Cited by in RCA: 210] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Nilbert M, Wikman FP, Hansen TV, Krarup HB, Orntoft TF, Nielsen FC, Sunde L, Gerdes AM, Cruger D, Timshel S, Bisgaard ML, Bernstein I, Okkels H. Major contribution from recurrent alterations and MSH6 mutations in the Danish Lynch syndrome population. Fam Cancer. 2009;8:75-83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Senter L, Clendenning M, Sotamaa K, Hampel H, Green J, Potter JD, Lindblom A, Lagerstedt K, Thibodeau SN, Lindor NM, Young J, Winship I, Dowty JG, White DM, Hopper JL, Baglietto L, Jenkins MA, de la Chapelle A. The clinical phenotype of Lynch syndrome due to germ-line PMS2 mutations. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:419-428. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 434] [Cited by in RCA: 404] [Article Influence: 23.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Zhang M, Yang H, Chen Z, Fan Y, Hu X, Liu W. Lynch syndrome-associated repeated stroke with MLH1 frame-shift mutation. Neurol Sci. 2021;42:1641. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ahadova A, Gallon R, Gebert J, Ballhausen A, Endris V, Kirchner M, Stenzinger A, Burn J, von Knebel Doeberitz M, Bläker H, Kloor M. Three molecular pathways model colorectal carcinogenesis in Lynch syndrome. Int J Cancer. 2018;143:139-150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 18.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Menahem B, Alves A, Regimbeau JM, Sabbagh C. Lynch Syndrome: Current management In 2019. J Visc Surg. 2019;156:507-514. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Vasen HFA. Progress Report: New insights into the prevention of CRC by colonoscopic surveillance in Lynch syndrome. Fam Cancer. 2022;21:49-56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ahadova A, Seppälä TT, Engel C, Gallon R, Burn J, Holinski-Feder E, Steinke-Lange V, Möslein G, Nielsen M, Ten Broeke SW, Laghi L, Dominguez-Valentin M, Capella G, Macrae F, Scott R, Hüneburg R, Nattermann J, Hoffmeister M, Brenner H, Bläker H, von Knebel Doeberitz M, Sampson JR, Vasen H, Mecklin JP, Møller P, Kloor M. The "unnatural" history of colorectal cancer in Lynch syndrome: Lessons from colonoscopy surveillance. Int J Cancer. 2021;148:800-811. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ladigan-Badura S, Vangala DB, Engel C, Bucksch K, Hueneburg R, Perne C, Nattermann J, Steinke-Lange V, Rahner N, Schackert HK, Weitz J, Kloor M, Kuhlkamp J, Nguyen HP, Moeslein G, Strassburg C, Morak M, Holinski-Feder E, Buettner R, Aretz S, Loeffler M, Schmiegel W, Pox C, Schulmann K; German Consortium for Familial Intestinal Cancer. Value of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy for gastric cancer surveillance in patients with Lynch syndrome. Int J Cancer. 2021;148:106-114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Therkildsen C, Joost P, Lindberg LJ, Ladelund S, Smith-Hansen L, Nilbert M. Renal cell cancer linked to Lynch syndrome: Increased incidence and loss of mismatch repair protein expression. Int J Urol. 2016;23:528-529. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ketabi Z, Bartuma K, Bernstein I, Malander S, Grönberg H, Björck E, Holck S, Nilbert M. Ovarian cancer linked to Lynch syndrome typically presents as early-onset, non-serous epithelial tumors. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;121:462-465. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Groth JV, Prabhu S, Periakaruppan R, Ohlander S, Emmadi R, Kothari R. Coexistent Dedifferentiated Endometrioid Carcinoma of the Uterus and Adenocarcinoma of the Bladder in Lynch Syndrome: Case Report and Review of the Literature. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2020;28:e26-e30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Phelan A, Lopez-Beltran A, Montironi R, Zhang S, Raspollini MR, Cheng M, Kaimakliotis HZ, Koch MO, Cheng L. Inherited forms of bladder cancer: a review of Lynch syndrome and other inherited conditions. Future Oncol. 2018;14:277-290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ten Broeke SW, Suerink M, Nielsen M. Response to Roberts et al. 2018: is breast cancer truly caused by MSH6 and PMS2 variants or is it simply due to a high prevalence of these variants in the population? Genet Med. 2019;21:256-257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Tjalsma AS, Wagner A, Dinjens WNM, Ewing-Graham PC, Alcalá LSM, de Groot MER, Hamoen KE, van Hof AC, Hofhuis W, Hofman LN, Hoogduin KJ, Kaijser J, Makkus ACF, Mol SJJ, Plaisier GM, Schelfhout K, Smedts HPM, Smit RA, Timmers PJ, Vencken PMLH, Visschers B, van der Wurff AAM, van Doorn HC. Evaluation of a nationwide Dutch guideline to detect Lynch syndrome in patients with endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2021;160:771-776. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Stinton C, Fraser H, Al-Khudairy L, Court R, Jordan M, Grammatopoulos D, Taylor-Phillips S. Testing for lynch syndrome in people with endometrial cancer using immunohistochemistry and microsatellite instability-based testing strategies - A systematic review of test accuracy. Gynecol Oncol. 2021;160:148-160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Chen W. Cancer statistics: updated cancer burden in China. Chin J Cancer Res. 2015;27:1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Cui MH, Zhang XW, Yu T, Huang DW, Jia Y. PMS2 germline mutation c.1577delA (p.Asp526Alafs*69)-induced Lynch syndrome-associated endometrial cancer: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98:e18279. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Kumar A, Paramasivam N, Bandapalli OR, Schlesner M, Chen T, Sijmons R, Dymerska D, Golebiewska K, Kuswik M, Lubinski J, Hemminki K, Försti A. A rare large duplication of MLH1 identified in Lynch syndrome. Hered Cancer Clin Pract. 2021;19:10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Song XJ, Liu ZL, Zeng R, Ye W, Liu CW. A meta-analysis of laparoscopic surgery vs conventional open surgery in the treatment of colorectal cancer. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98:e15347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Rohlin A, Rambech E, Kvist A, Törngren T, Eiengård F, Lundstam U, Zagoras T, Gebre-Medhin S, Borg Å, Björk J, Nilbert M, Nordling M. Expanding the genotype-phenotype spectrum in hereditary colorectal cancer by gene panel testing. Fam Cancer. 2017;16:195-203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Jia S, Zhang M, Sun Y, Yan H, Zhao F, Li Z, Ji J. A Chinese family affected by lynch syndrome caused by MLH1 mutation. BMC Med Genet. 2018;19:106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Solassol J, Larrieux M, Leclerc J, Ducros V, Corsini C, Chiésa J, Pujol P, Rey JM. Alu element insertion in the MLH1 exon 6 coding sequence as a mutation predisposing to Lynch syndrome. Hum Mutat. 2019;40:716-720. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Li Y, Salo-Mullen E, Varghese A, Trottier M, Stadler ZK, Zhang L. Insertion of an Alu-like element in MLH1 intron 7 as a novel cause of Lynch syndrome. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2020;8:e1523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Hong J, Kim H, Hong YS, Lee W, Lim S-B, Byeon J-S, Chun S, Min W-K. A Case of Lynch Syndrome with the Deletion of Multiple Exons of the MLH1 Gene, Detected by Next-Generation Sequencing. J Lab Med Qual Assur. 2019;41:220-224. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 32. | Lagerstedt-Robinson K, Rohlin A, Aravidis C, Melin B, Nordling M, Stenmark-Askmalm M, Lindblom A, Nilbert M. Mismatch repair gene mutation spectrum in the Swedish Lynch syndrome population. Oncol Rep. 2016;36:2823-2835. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Singh S, Resnick KE. Lynch Syndrome and Endometrial Cancer. South Med J. 2017;110:265-269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Wang Y, Wang Y, Li J, Cragun J, Hatch K, Chambers SK, Zheng W. Lynch syndrome related endometrial cancer: clinical significance beyond the endometrium. J Hematol Oncol. 2013;6:22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Vasen HF, Watson P, Mecklin JP, Lynch HT. New clinical criteria for hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC, Lynch syndrome) proposed by the International Collaborative group on HNPCC. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:1453-1456. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1765] [Cited by in RCA: 1688] [Article Influence: 64.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Umar A, Boland CR, Terdiman JP, Syngal S, de la Chapelle A, Rüschoff J, Fishel R, Lindor NM, Burgart LJ, Hamelin R, Hamilton SR, Hiatt RA, Jass J, Lindblom A, Lynch HT, Peltomaki P, Ramsey SD, Rodriguez-Bigas MA, Vasen HF, Hawk ET, Barrett JC, Freedman AN, Srivastava S. Revised Bethesda Guidelines for hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (Lynch syndrome) and microsatellite instability. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:261-268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2154] [Cited by in RCA: 2219] [Article Influence: 105.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 37. | Buchanan DD, Tan YY, Walsh MD, Clendenning M, Metcalf AM, Ferguson K, Arnold ST, Thompson BA, Lose FA, Parsons MT, Walters RJ, Pearson SA, Cummings M, Oehler MK, Blomfield PB, Quinn MA, Kirk JA, Stewart CJ, Obermair A, Young JP, Webb PM, Spurdle AB. Tumor mismatch repair immunohistochemistry and DNA MLH1 methylation testing of patients with endometrial cancer diagnosed at age younger than 60 years optimizes triage for population-level germline mismatch repair gene mutation testing. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:90-100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 172] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Provenzale D, Gupta S, Ahnen DJ, Bray T, Cannon JA, Cooper G, David DS, Early DS, Erwin D, Ford JM, Giardiello FM, Grady W, Halverson AL, Hamilton SR, Hampel H, Ismail MK, Klapman JB, Larson DW, Lazenby AJ, Lynch PM, Mayer RJ, Ness RM, Regenbogen SE, Samadder NJ, Shike M, Steinbach G, Weinberg D, Dwyer M, Darlow S. Genetic/Familial High-Risk Assessment: Colorectal Version 1.2016, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2016;14:1010-1030. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 157] [Article Influence: 19.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Giardiello FM, Allen JI, Axilbund JE, Boland CR, Burke CA, Burt RW, Church JM, Dominitz JA, Johnson DA, Kaltenbach T, Levin TR, Lieberman DA, Robertson DJ, Syngal S, Rex DK. Guidelines on genetic evaluation and management of Lynch syndrome: a consensus statement by the US Multi-society Task Force on colorectal cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:1159-1179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 308] [Cited by in RCA: 311] [Article Influence: 28.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Goodfellow PJ, Billingsley CC, Lankes HA, Ali S, Cohn DE, Broaddus RJ, Ramirez N, Pritchard CC, Hampel H, Chassen AS, Simmons LV, Schmidt AP, Gao F, Brinton LA, Backes F, Landrum LM, Geller MA, DiSilvestro PA, Pearl ML, Lele SB, Powell MA, Zaino RJ, Mutch D. Combined Microsatellite Instability, MLH1 Methylation Analysis, and Immunohistochemistry for Lynch Syndrome Screening in Endometrial Cancers From GOG210: An NRG Oncology and Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:4301-4308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 15.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Kwon JS, Scott JL, Gilks CB, Daniels MS, Sun CC, Lu KH. Testing women with endometrial cancer to detect Lynch syndrome. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2247-2252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Piñol V, Castells A, Andreu M, Castellví-Bel S, Alenda C, Llor X, Xicola RM, Rodríguez-Moranta F, Payá A, Jover R, Bessa X; Gastrointestinal Oncology Group of the Spanish Gastroenterological Association. Accuracy of revised Bethesda guidelines, microsatellite instability, and immunohistochemistry for the identification of patients with hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. JAMA. 2005;293:1986-1994. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 389] [Cited by in RCA: 395] [Article Influence: 19.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Yoshihama T, Hirasawa A, Sugano K, Yoshida T, Ushiama M, Ueki A, Akahane T, Nanki Y, Sakai K, Makabe T, Yamagami W, Susumu N, Kameyama K, Kosaki K, Aoki D. Germline multigene panel testing revealed a BRCA2 pathogenic variant in a patient with suspected Lynch syndrome. Int Cancer Conf J. 2021;10:6-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Kasela M, Nyström M, Kansikas M. PMS2 expression decrease causes severe problems in mismatch repair. Hum Mutat. 2019;40:904-907. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Wang WM. Optimization strategy and screening status of colorectal cancer related Lynch syndrome with MLH1 deletion in Chinese population. Annals of Oncology. 2018;29:viii176-viii177. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |