Published online Jul 16, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i20.6954

Peer-review started: September 13, 2021

First decision: November 22, 2021

Revised: December 4, 2021

Accepted: May 26, 2022

Article in press: May 26, 2022

Published online: July 16, 2022

Processing time: 294 Days and 23.1 Hours

Enteroatmospheric fistula (EAF) is a catastrophic complication that can occur after open abdomen. EAFs cause severe body fluid loss, hypercatabolism, and wound complications, leading to adverse clinical outcomes.

A 72-year-old female patient underwent ventral hernia repair. Five days after the surgery, she exhibited severe abdominal pain with septic shock. Exploratory laparotomy revealed extensive intestinal adhesions and severe intraperitoneal contamination. Since the patient was hemodynamically unstable, a salvage operation rather than definite surgery was needed, and three surgical open drains were inserted into the peritoneal cavity. Postoperative EAFs developed, and it was almost impossible to isolate and reduce the fistula output despite the use of vacuum-assisted closure dressings and endoscopic stent insertion. Finally, we anastomosed two vascular grafts to the openings of each EAF to restore enteric continuity. The inserted vascular grafts showed acceptable patency, and the patient could receive optimal nutritional support with elemental enteral feeding. She underwent EAF resection 76 d after graft implantation.

Control of the enteric effluent are key elements in achieving favorable clinical conditions which should precede definite surgery for EAFs.

Core Tip: Enteroatmospheric fistula (EAF) is a catastrophic complication that can occur after open abdomen. EAFs cause severe body fluid loss, hypercatabolism, and wound complications, leading to adverse clinical outcomes. Small and low-output EAFs might be managed by “reduction and isolation” strategies with vacuum assisted closed dressings to achieve spontaneous healing, while large and high-output EAFs should be resected when the patients are clinically stable. Infection control and management of the enteric effluent are key elements in achieving favorable clinical conditions which should precede definite surgery for EAFs.

- Citation: Cho J, Sung K, Lee D. Management of the enteroatmospheric fistula: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(20): 6954-6959

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i20/6954.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i20.6954

An enterocutaneous fistula (ECF) is an enteric fistula arising from the viscus organs within the peritoneum, such as the colon, stomach, and small intestine. Enteroatmospheric fistula (EAF) is an exposed ECF, and it usually develops as a complication of open abdomen. Patients with EAF have high rates of morbidities, which include fluid and electrolyte loss, acid-base imbalance, hypercatabolism, vitamin and trace element deficiencies, and wound complications[1]. We recently treated a patient who exhibited EAFs after ventral hernia repair. It was challenging to protect the surrounding skin from the enteric effluent and to deliver optimal nutritional support for this patient because it was almost impossible to isolate and reduce the fistula output. In this report, we introduce our method to control the bowel effluent from the EAF and discuss the appropriate treatment strategy for patients with high-output EAF.

A 72-year-old female patient presented two EAFs on her abdomen.

This patient visited our outpatient department with a complaint of bulging mass on her low abdomen, and underwent ventral hernia repair in our hospital. Five days after the surgery, she exhibited severe abdominal pain with septic shock. Exploratory laparotomy revealed extensive intestinal adhesions and severe intraperitoneal contamination. Since the patient was hemodynamically unstable, we could not aggressively dissect the adhesions; instead, we removed the mesh and performed blunt dissection toward the suspected injury sites and placed three open drain systems as a salvage strategy (Figure 1). Although critical care was challenging for this patient, the systemic infection was gradually resolved postoperatively, and two EAFs were developed eventually.

She had no known medical comorbidities except for well-controlled hypertension and diabetes.

She had no personal and family history.

We found a bulging mass on her low abdomen, and there were no symptoms or signs of the intestinal obstruction.

No abnormalities were found on the laboratory examinations, including complete blood cell count, cardiac markers, and coagulation profile.

An abdominal computed tomography scan demonstrated the EAF of this patient (Figure 2).

The final diagnosis of the presented case is the postoperative EAF.

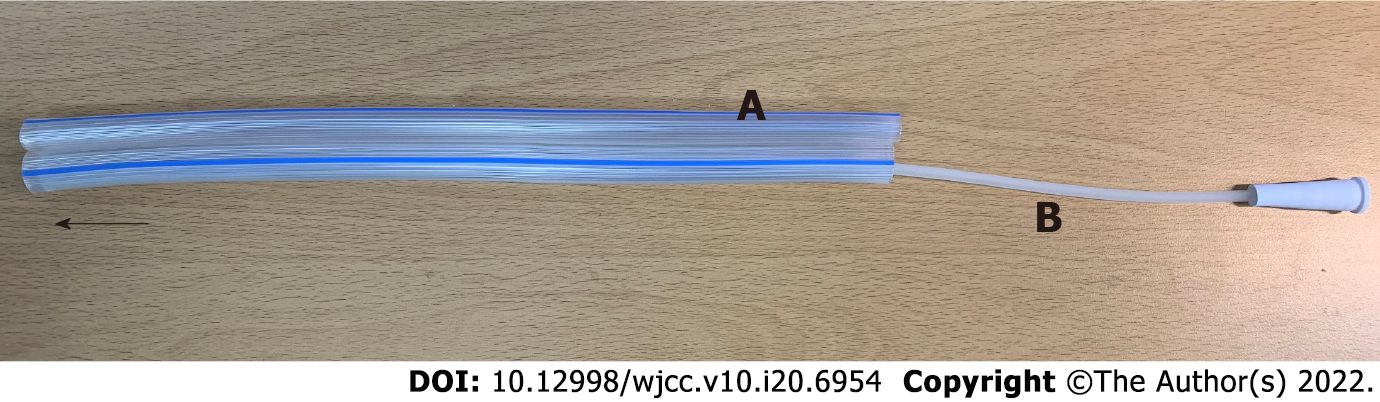

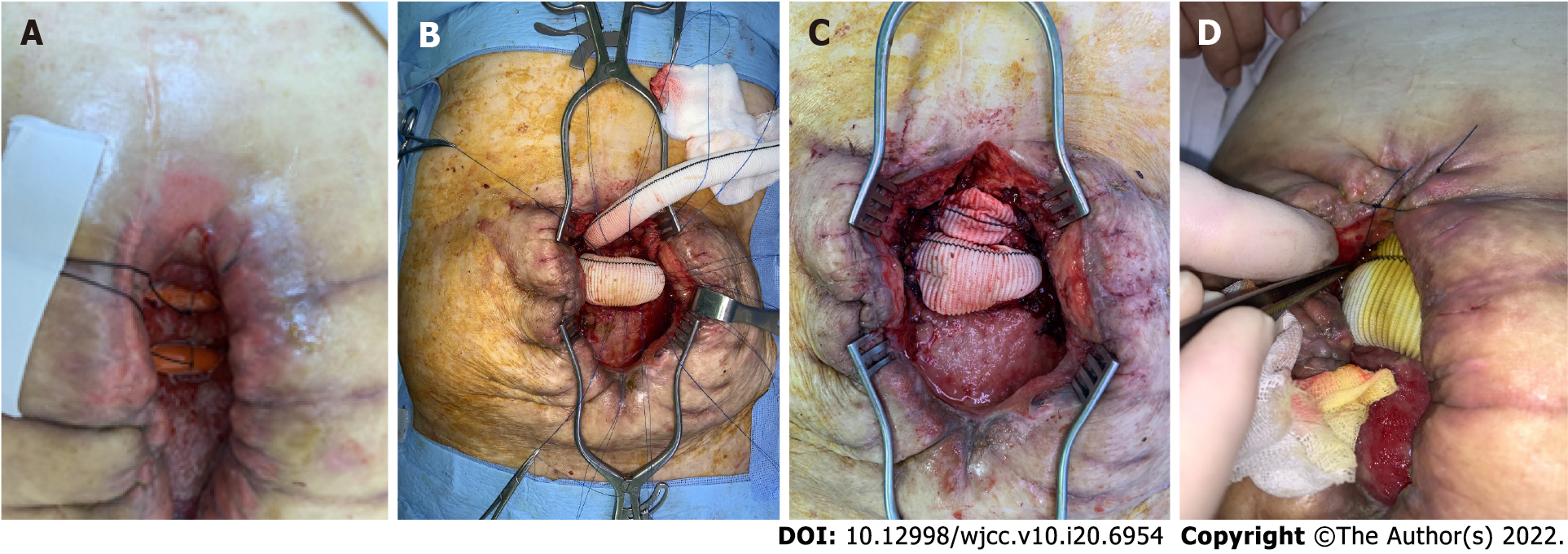

To achieve spontaneous closure of the EAFs, fasting with full caloric parenteral nutrition (PN), electrolyte repletion, antacids, octreotide, and frequent surgical wound dressing with protection of the surrounding tissue from the enteric effluent were applied in this case. However, the daily output of the EAFs consistently exceeded 1000 mL, and the surrounding tissues were severely contaminated by enteric effluent despite the use of vacuum-assisted closure (VAC) dressings. Moreover, the initiation of enteral nutrition (EN) was impossible because the output increased dramatically whenever EN was attempted. We should have reduced the fistula output to improve the patient’s clinical condition. First, we opened the surgical wound and inserted rubber drains into the intestinal lumens to reduce the fistula output (Figure 3A). This strategy worked temporally during fasting, and the fistula output decreased to < 500 mL/d; however, the fistula output returned to > 1000 mL/d as soon as EN was started, although the EN was elemental. We found that the diameter of the inserted rubber drains was insufficient for the enteric flow. Thus, endoscopic stent insertion was attempted; however, this strategy also failed because the efferent and afferent limbs of the EAFs appeared to have sharp angles, causing expulsion of the inserted stents. Subsequently, on the 32nd postoperative delirium (POD), we implanted two vascular grafts (GELWEAGETM straights, Vasuteck Limited, Inchinnan, United Kingdom) between the openings of each EAF to restore enteric continuity (Figures 3B and C). The two EAFs had a total of 4 openings, and the two openings of each EAF could be identified because the posterior walls of the intestine were attached to each other. Anastomoses between the intestinal openings of each EAF and the vascular grafts were performed via the interrupted suture technique (Figure 3B). After the operation, no fistula output was observed, and elemental EN began on the 5th POD. Although the anastomoses were not completely healed and there was some leakage after the initiation of EN (Figure 3D), the anastomosed vascular graft showed acceptable patency. The output remained < 300 mL/d, and the patient became comfortable clinically and emotionally. EN did not proceed to polymeric formulas, and elemental EN was maintained for the risk of anastomosis breakdown.

The patient could be discharged from the hospital with a VAC dressing on the 16th POD after graft implantation (on the 53rd POD after ventral hernia repair) and received VAC dressing management regularly at the outpatient department. Two months after discharge, she underwent EAF resection, and the involved intestines were the distal jejunum and sigmoid colon.

EAF is not a true fistula, as it has no fistula tract, and can be caused by the following conditions: (1) Anastomosis leakage; (2) Temporary abdominal closure; (3) Adhesions between the edematous intestine and the abdominal wall; (4) Surgical site infection; (5) Burst abdomen; and (6) Bowel ischemia[1]. Among 517 patients from The American Association for Surgery in Trauma open abdomen registry, 111 (21%) developed ECF, EAF, or intra-abdominal sepsis[2]. The incidence of EAF has been reported to be 2% to 25% in trauma patients, 20% to 25% in patients with abdominal sepsis, and 50% in patients with pancreas necrosis[3]. A multivariate prognostic analysis from China demonstrated that sepsis, multiorgan dysfunction syndrome, and hemorrhage were independent risk factors for death in ECF patients, and that active lavage and drainage were protective factors[4]. Therefore, fistula-associated abdominal sepsis should be recognized and promptly treated with source control. Control of abdominal sepsis can reduce the mortality of patients with EAF[5,6]. Once sepsis and peritonitis are controlled in patients with ECF, conservative treatment can be performed for spontaneous closure of the fistula. However, in patients with EAF, spontaneous closure cannot be expected; therefore, isolation and reduction of the enteric effluent is required to achieve an optimal intra-abdominal environment and stable clinical condition for definite surgery. Various techniques using VAC dressings have been introduced to isolate enteric effluent from the surrounding tissue[7-9]. However, these methods cannot reduce the output volume; therefore, anticathartics, somatostatin analogs, antisecretories, and cholestyramine might be considered for patients with high-output fistulas[10], because fistula output reduction is crucial for simplifying fluid therapy, performing wound management, providing optimal nutritional support, and applying nursing practices. If these strategies are successful in controlling the enteric effluent, the patients can undergo definite surgery after achieving favorable clinical conditions. Such conditions might be achieved in some patients after 1-2 mo, while some patients may even need 1 year[11,12]. Fistula can cause an intraperitoneal inflammatory response and severe adhesions, for which early surgery might be dangerous[13]. The unfavorable abdominal environment can persist for 6-8 wk after exposure in the open abdominal wound[14]. One study reported that surgery-related mortality was significantly high in the period between 11 and 42 d after the development of a fistula[13]. However, in patients with high-output EAF unresponsive to isolation/reduction treatments, persistent wound contamination and malnutrition might worsen the clinical course, and it can be impossible to achieve optimal conditions for definite surgery. Our patient exhibited massive EAF output despite pharmacologic treatments and the use of a VAC dressings. We should have reduced the fistula output to improve the patient’s clinical condition. However, intraluminal approaches to reduce fistula output by restoring intestinal continuity failed. The surrounding skin was severely contaminated, causing septic wound complications, and prolonged PN eventually resulted in catheter-related complications, hepatic dysfunction, nutritional imbalance, and emotional problems. Finally, we noticed that both the efferent and afferent intestines to the EAFs were clearly exposed; therefore, we could anastomose them with vascular grafts. Although the anastomoses did not heal completely due to insufficient cellular ingrowth, intestinal edema, and an indistinct serosal layer, the enteric outflow could be controlled after the procedure. Furthermore, the additional use of VAC dressings played a key role in isolating the enteric outflow.

The EAF is a challenging condition with high morbidity and mortality rates. Small and low-output EAFs might be managed by “reduction and isolation” strategies with VAC dressings to achieve spontaneous healing, while large and high-output EAFs should be resected when the patients are clinically stable. The method introduced in this report can control enteric outflow in patients with EAFs unresponsive to conventional treatments, and this approach can be helpful in achieving favorable clinical conditions for definite surgery.

The authors thank to our surgical residents and surgical critical nursing team for their sincere assistance in surgery and post-operative management.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Gu GL, China; Lima R, Chile A-Editor: Lin FY, China S-Editor: Wang JJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wang JJ

| 1. | Marinis A, Gkiokas G, Argyra E, Fragulidis G, Polymeneas G, Voros D. "Enteroatmospheric fistulae"--gastrointestinal openings in the open abdomen: a review and recent proposal of a surgical technique. Scand J Surg. 2013;102:61-68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Bradley MJ, Dubose JJ, Scalea TM, Holcomb JB, Shrestha B, Okoye O, Inaba K, Bee TK, Fabian TC, Whelan JF, Ivatury RR; AAST Open Abdomen Study Group. Independent predictors of enteric fistula and abdominal sepsis after damage control laparotomy: results from the prospective AAST Open Abdomen registry. JAMA Surg. 2013;148:947-954. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Becker HP, Willms A, Schwab R. Small bowel fistulas and the open abdomen. Scand J Surg. 2007;96:263-271. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Zheng T, Xie HH, Wu XW, Chi Q, Wang F, Yang ZH, Chen CW, Mai W, Luo SM, Song XF, Yang SM, Zhou W, Liu HY, Xu XJ, Zhou Z, Liu CY, Ding LA, Xie K, Han G, Liu HB, Wang JZ, Wang SC, Wang PG, Wang GF, Gu GS, Ren JA. [Investigation of treatment and analysis of prognostic risk on enterocutaneous fistula in China: a multicenter prospective study]. Zhonghua Wei Chang Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2019;22:1041-1050. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Annibali R, Pietri P. Fistulous complications of Crohn's disease. Int Surg. 1992;77:19-27. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Brooks NE, Idrees JJ, Steinhagen E, Giglia M, Stein SL. The impact of enteric fistulas on US hospital systems. Am J Surg. 2021;221:26-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Goverman J, Yelon JA, Platz JJ, Singson RC, Turcinovic M. The "Fistula VAC," a technique for management of enterocutaneous fistulae arising within the open abdomen: report of 5 cases. J Trauma. 2006;60:428-31; discussion 431. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Al-Khoury G, Kaufman D, Hirshberg A. Improved control of exposed fistula in the open abdomen. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206:397-398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Verhaalen A, Watkins B, Brasel K. Techniques and cost effectiveness of enteroatmospheric fistula isolation. Wounds. 2010;22:212-217. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Bleier JI, Hedrick T. Metabolic support of the enterocutaneous fistula patient. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2010;23:142-148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Jamshidi R, Schecter WP. Biological dressings for the management of enteric fistulas in the open abdomen: a preliminary report. Arch Surg. 2007;142:793-796. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Marinis A, Gkiokas G, Anastasopoulos G, Fragulidis G, Theodosopoulos T, Kotsis T, Mastorakos D, Polymeneas G, Voros D. Surgical techniques for the management of enteroatmospheric fistulae. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2009;10:47-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Fazio VW, Coutsoftides T, Steiger E. Factors influencing the outcome of treatment of small bowel cutaneous fistula. World J Surg. 1983;7:481-488. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hill GL. Operative strategy in the treatment of enterocutaneous fistulas. World J Surg. 1983;7:495-501. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |